Albert Edelfelt: Modern Artist Life in Fin-de-Siècle Europe

Reviewed by David SmithDavid Smith

Professor

University of Oxford

Email the author: david.smith[at]pharm.ox.ac.uk

Citation: David Smith, exhibition review of Albert Edelfelt: Modern Artist Life in Fin-de-Siècle Europe, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.1.19.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Albert Edelfelt: Modern Artist Life in Fin-de-Siècle Europe

Gothenburg Museum of Art

October 22, 2022–March 12, 2023

Catalogue:

Eva Nygårds and Patrik Steorn, eds.,

Albert Edelfelt: A Modern Artist in Fin-de-Siècle Europe.

Gothenburg: Gothenburg Museum of Art; Stockholm: Appell Förlag, 2022.

200 pp.; 100 color illus.; bibliography; chronology; notes and references; index of names.

€31 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978–91–986644–3–0

Albert Edelfelt (1854–1905) is considered Finland’s first great artist. This exhibition, which was first shown at the Petit Palais in Paris, is a good opportunity to see many of the works that established his reputation and inspired younger Finnish artists. In three large rooms, a broad selection of seventy-four paintings and eight illustrations are spaciously and sensitively displayed. They come from his total output of 1,104 paintings (oils, pastels, and watercolors) and many illustrations. A catalogue with useful background essays including new research and a chronology accompanies the exhibition; the book would be a good introduction to this artist for newcomers.

Edelfelt, son of a Swedish-born father, showed early promise and went to the drawing school of the Finnish Art Society when he was fourteen and then on to the Imperial University in Helsinki (Finland was still part of Russia). The enlightened state gave him a scholarship to go to the Antwerp Academy to study painting because it was keen to have art that reflected the history of the country. Edelfelt did well and soon moved to Paris to continue his studies. From that time on, he became a “Parisian” for part of each year until he died, but every summer he returned to his mother’s house at Haikko on the south coast of Finland. This duality forms the basis of his art, because although he learned a great deal, made useful contacts, and found beautiful models in Paris, his own country and people gave him his greatest inspiration. Early on in Paris, Edelfelt became aware of plein-air painting, and in 1875 he met Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848–84), who taught him the importance of drawing and of light. Although this was the period when the impressionists were developing, Edelfelt did not follow their style, but may have been influenced by their philosophy. Indeed, one might say that Edelfelt adopted French realism but illuminated it with the glow of Nordic light. The entrance to the exhibition reflects this very well with a display of some of his “sunshine pieces,” as he called them (12, fig. 1). Shown here are Girls in a Rowing Boat (1886, fig. 2), in which the sea brightly reflects the sky, and Under the Birches II (1882, fig. 3), which shows two young women (perhaps Edelfelt’s sisters) sitting under birch trees. The depiction of the sunlight in the forest has surely never been surpassed. Other fine examples of sunshine pieces are shown later in the exhibition, notably Boys Playing on the Shore (1884) and Shipbuilders (1886).

After the sunshine pieces come some early portraits of Edelfelt’s mother and three sisters. A portrait of his mother is particularly striking: Portrait of the Artist’s Mother, Alexandra Edelfelt (1883, fig. 4), shows a woman whose demeanor is calm, strong, and caring. She was crucially his main support after his father died when Edelfelt was fourteen. He wrote hundreds of letters to her throughout his life and constantly sought her advice. There are also remarkable portraits from 1883 of his sisters Annie in profile, following Renaissance style, and Ellen done when the artist was twenty-two years old (fig. 5). The tenderness is palpable, as is the great technical skill, for example in the depiction of her hands. This painting is one of his first great works and is especially moving when we know that Ellen died, aged seventeen, from tuberculosis a few weeks after it was painted.

In Paris Edelfelt primarily painted portraits because they brought in money. His breakthrough came with his historical “portrait” of the medieval Swedish Queen Blanche (known as Bianca) with her young son, Haakon, on her lap (fig. 6). Edelfelt was developing skill at portraying basic human emotions; this painting clearly depicts joy and maternal love, possibly reflecting his relationship with his own mother. After acceptance to the Salon in Paris in 1877, the painting was reproduced widely and featured in many homes in France as well as Finland and Sweden. It remains one of his most popular works. From that time on, Edelfelt was much in demand for portraits, which comprise about half of his output, and he executed commissions for the Russian and Danish royal families. Edelfelt got to know Anders Zorn (1860–1920) and John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) in Paris and was considered their equal in portraiture. His most famous portrait (only a study is displayed in the exhibition) was of Louis Pasteur (1885). The portrait is novel because it is not “posed” but shows Pasteur active in his laboratory, handling a flask. It won the Grand Prix in the Salon of 1886 and then a gold medal at the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1899, after which Edelfelt was appointed an Officer of the Legion of Honor, a high rank for someone so young (aged thirty-five). The work was acquired by the French state and has virtually become a national treasure; it is on display at the Musée d’Orsay.

Another group of portraits done in Paris focuses on Edelfelt’s many models. One of his favorites, who became his mistress, was Virginie and she appears in several paintings in the exhibition, including the captivating Virginie (Parisienne) (1883, fig. 7) done in his studio with a Japanese screen as background.

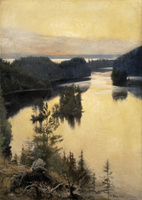

In addition to painting portraits in Paris, Edelfelt sometimes brought his “Nordic light” into a local scene, as in The Luxembourg Gardens, Paris (1887, fig. 8), which is one of the only large works he painted set in Paris. As a result, it has become iconic as a representation of Edelfelt’s view of his adopted city. It is shown to great effect in the exhibition (fig. 9), with its skillful rendering of light and shade with brilliant, dappled sunlight on the sand; it is a painting full of the joy of life. The contrast in style, although not in spirit, with an 1895 work by Felix Vallotton (1865–1925) bearing the same title is striking. Edelfelt was perhaps not a natural landscape artist, but the exhibition shows one of his finest works in the genre, Kaukola Ridge at Sunset (1889, fig. 10). Its japoniste aspects, including the high horizon popular at the time in Paris, must have influenced later Finnish landscape artists such as Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865–1931).[1]

For Edelfelt, the Finnish landscape was not so much an object on its own as a setting in his paintings that depict the full range of human emotions, including tenderness, love, devotion, fortitude, joy, and sorrow. Many paintings in the exhibition illustrate this approach. Sorrow dominates Conveying the Child’s Coffin (1879, fig. 11), a plein-air painting that movingly depicts a journey to a child’s funeral. It is hard to imagine a more unusual setting for such a theme, demonstrating Edelfelt’s genius for finding Finnish landscapes that echo human emotions. Note how, by cutting off the boat’s bow in the painting, Edelfelt has projected the viewer into the boat to join the family. The contrast between the bright sky and background and the somber interior of the boat heightens the feeling of sorrow. This masterpiece was an instant success in France (but apparently not in Finland) and received a bronze medal at the 1880 Salon in Paris, the first work by a Finnish artist to receive a medal. In response to an inaccurate account of the prize medal in a Finnish newspaper, Edelfelt wrote, “It is the first time any Finn has received a medal; the first time any Finn has been spoken of as an artist; the first time that a painting with a Finnish subject has attracted general attention in Paris” (154).

Tenderness is found in Christ and Mary Magdalene, a Finnish Legend (1890, fig. 12), which is set on the forested shoreline of a Finnish lake and shows Jesus in peasant shoes made from birch-bark and Mary in typical Karelian ethnic dress from eastern Finland. The title reveals that the painting was not inspired by the Bible but from the Kanteletar, a collection of Finnish poetry by Elias Lönnrot (1802–84). In a poem entitled “Mary Magdalene’s Journey by Water,” we find the stanza:

Make me Lord Jesus,

Take me where you want

Back to the sea then

As rotten wood for waves,

Tossed by every wind,

On top of a wide wave

In the painting, the expression of devotion in Mary’s face is striking, as is the tenderness revealed by Jesus’s posture; both these emotions are enhanced by the natural setting. Another painting, Sorrow (1894, fig. 13), was inspired by a Carl Snoilsky (1841–1903) poem about a young couple from Värnamo, Sweden, who were forced to indefinitely postpone their marriage. Again, the setting, with a large group of cut-down tree-trunks, intensifies the emotion.

Fortitude is shown in an evocative work called simply In the Outer Archipelago (1898, fig. 14), which depicts a man and two women determinedly carrying what appears to be the mast and oars from a fishing boat. We can only assume that they are on an important mission. This painting was done at a time when the authorities were conducting a campaign of “Russification” of society, causing many Finns to view Russia as a threat. As Soili Sinisalo has observed, “Edelfelt has given [the figures] a defiant power, and he seems to have wanted to communicate the idea of unshakeable will and an invincible ability to defend the country. . . . The painting was copied and spread through Finnish homes as a kind of manifesto of the people’s will to defend themselves.”[2] A different kind of fortitude can be found in a large painting that is well displayed in the exhibition at eye-level in a prominent position (fig. 15). This work, called At Sea (1883, fig. 16), differs markedly from the sketch shown beside it, which depicts a sunny day; in the final work we see a fisherman and a girl in a boat that is straining in a strong sea, seemingly before a brewing storm. Their expressions combine a sense of anxiety with determination. Edelfelt’s choice of a girl rather than another man gives added tension to the situation. He was especially fond of depicting women, which may reflect his lifelong closeness to his mother and three sisters. This work is a treasured part of the collection of the Gothenburg Museum of Art, purchased soon after it was first exhibited in Paris in 1883. Notably, in the same year Gothenburg was the first Swedish city to hold a retrospective exhibition for Edelfelt. Such exhibitions were not common at that time.

A good example of the inspiration landscape gave to Edelfelt’s expressions of human emotions is a plein-air painting done in Finland, Divine Service in the Uusimaa Archipelago (1881, fig. 17), whose genesis is well described by Marina Catani in the catalogue (72–83). Edelfelt took several trips to identify a site in which to set the subject. This large canvas (almost two meters wide) contains depictions of nineteen figures. Edelfelt worked intensely on it over a period of two months in 1881, each time having to carry the canvas several kilometers from his home to the site. The final picture creates a sense of both collective and individual devotion. The models were drawn from local people, and reward careful study. Such a study was performed by Vincent van Gogh (1853–90) as we learn from a letter he wrote to his brother Theo in 1883:

This week I found a reproduction of a picture by Edelfelt: A Prayer-Meeting on the Beach. There is something in it of Longfellow’s poems; it is very beautiful. It shows a sentiment of which I am very fond, and which I think does more good in the world than the Italians and Spaniards with their “Arms Merchants of Cairo,” of which I get so tired in the long run. This week I have been working on the figure of a woman on the heath, who is gathering cuts of peat. And a kneeling figure of a man. One must know the structure of the figures so thoroughly, in order to get the expression, at least I cannot see it differently. The Edelfelt is indeed beautiful in its expression, however the effect lies not only in the expression of the faces, but in the whole position of the figures.[3]

Van Gogh’s comments apply to most of Edelfelt’s works, and they are consistent with what Edelfelt himself wrote six years earlier: “Only a very few understand the historical accuracy and execution—but everyone understands the expression and life in the canvas, and in fact these are a condition sine qua non for every work of art. And that is how I would like to paint history: to make the costumes and the details entirely subordinate to the subject’s simple humanity, the part that is understandable to every man” (112).

Although most of the works in the exhibition are oil paintings, there are some fine pastels and several illustrations in ink, watercolor, and/or gouache. The illustrations are important as they belong to key works of Finnish/Swedish literature and were likely to have been the way most people at the time came across the artist. Overall, this beautifully presented and comprehensive exhibition gives an enriching and moving account of the work of a great artist; Edelfelt set the standard for a succession of outstanding fin-de-siècle Finnish artists and also inspired many other Nordic artists. His work should be much better known.

Notes

[1] Leena Ahtola-Moorhouse, “Landscapes,” in Albert Edelfelt: 1854–1905 Jubilee Book, ed. Lena Ahtola-Moorhouse (Helsinki: Ateneum Art Museum, 2004), 181.

[2] Soili Sinisalo, “Painting the People,” in Albert Edelfelt: 1854–1905 Jubilee Book, ed. Lena Ahtola-Moorhouse (Helsinki: Ateneum Art Museum, 2004), 108.

[3] Letter to Theo van Gogh, April 30, 1883, Vincent van Gogh: The Letters, https://vangoghletters.org/.