Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast

Reviewed by Caterina Y. PierreCaterina Y. Pierre

Professor, City University of New York, Kingsborough Community College

Visiting Associate Professor, The Pratt Institute

Email the author: caterina.pierre[at]kbcc.cuny.edu, cpierre[at]pratt.edu

Citation: Caterina Y. Pierre, exhibition review of Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.1.18.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

March 10, 2022–March 5, 2023

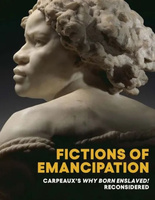

Catalogue:

Elyse Nelson and Wendy S. Walters, eds.,

Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux’s Why Born Enslaved! Reconsidered.

New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2022.

140 pp.; 81 illus.; bibliography (“further reading”); chronology; exhibition checklist; index; notes.

$25.00 (softcover)

ISBN: 978–1–58839–744–7

In 2019, the Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased a marble sculpture of Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s (1827–75) Why Born Enslaved! (fig. 1), his well-known bust of a bound female African figure that was produced in various materials from 1868 until well after his death by his atelier in 1875. Soon after this purchase, the murder of George Floyd (1973–2020) in the summer of 2020 prompted many people to reconsider the history of race in this country and the question of freedom in our own times. In the wake of this turning point in US history, the Metropolitan mounted this exhibition, Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast as a dossier exhibition (a one-room show, jam-packed with ceramics, ephemera, paintings, sculptures, and works on paper) to explore the issues surrounding Carpeaux’s bust, as well as other images of enslaved or emancipated figures from the period. Nineteenth-century sculptures by pre-eminent sculptors of Carpeaux’s time, including Edmonia Lewis (1844–1907) and Charles-Henri-Joseph Cordier (1827–1905) were also on view, as well as some eighteenth-century works, in particular by Louis Simon Boizot (1743–1809), and two contemporary sculptures, one by Kehinde Wiley (b. 1977) and another by Kara Walker (b. 1969).

The overriding question of the exhibition is whether Why Born Enslaved! should be considered as proof of Carpeaux’s abolitionist leanings. The colonialist aspects of the sculpture had not been previously explored. Save for his allegorical image of Africa for the Fountain of the Observatory, Avenue de l’Observatoire, Paris (1867–74), Why Born Enslaved! is the only example of an African figure in Carpeaux’s oeuvre. The artist cared enough about the subject and the sculpture that he submitted the original marble version (now at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen), with his portrait bust of Charles Garnier (1825–98) in bronze, to the Paris Salon exhibition of 1869, under the title Négresse.[1] The current title “Why Born Enslaved!” comes from the words “pourquoi naître esclave!” carved into the front of the original marble, the Metropolitan’s marble, and terracotta versions of the sculpture, as well as other examples.[2] But what were Carpeaux’s true motives in making this bust? Was it just a remnant of the allegorical figure of Africa that he was concurrently working on for the Fountain of the Observatory, an easy artwork to crib and submit to the exhibition? Was it simply a money-making endeavor, a sculpture Carpeaux knew he could sell in a growing anti-racist market, particularly in France and the United States, the latter of which had recently abolished slavery? Was it made to mark the twentieth anniversary of the end of slavery in 1868? Or was the sculpture about the equality of all people, the evils of enslavement, or the outrage of racialized bondage?

By 1868, when Carpeaux first produced Why Born Enslaved!, the image of the slave, whether emancipated or not, was popular among both abolitionists and people who wanted to be seen as what we might call today “woke” to the changes of the times: the institution of slavery as it was known then had only recently been abolished (in the British Empire, in 1833; in France, in 1848; and in the United States, in 1865).[3] There is also a suggestion in the exhibition and the accompanying catalogue (edited by Elyse Nelson and Wendy S. Walters) that Carpeaux’s Why Born Enslaved! would have also appealed to people who still longed for a past in which colonial power and white dominance went unquestioned (53). Nelson, in her catalogue essay, notes that the bust “spoke the humanitarian language of empathy while simultaneously giving powerful visual form to the desire for domination over non-Europeans” (53). I doubt that Carpeaux’s sculpture, with its carved declaration that clearly questions why someone is born into slavery, would work very well as part of the décor of the home of the typical nineteenth-century racist. Not all the versions of the sculpture, however, contained the carved declaration, and unfortunately the motives of individual buyers of this sculpture are, as far as I am aware, unrecorded.

Upon entering Gallery 521 through the Medieval Art gallery at the Metropolitan on the museum’s main floor, the visitor is presented face-on with Why Born Enslaved! in its marble edition, one of only two known versions in this material (fig. 2). It had only been exhibited once before, at a posthumous exhibition of Carpeaux’s works at the Jeu de Paume in Paris in 1912. The work remained in private collections until 2018. While it has some staining and veining, the marble is finely carved. The expression of the female figure is arresting; she looks away and upwards, her brow knitted, as if she is being admonished but she resists (see fig. 1). She is not young, and her expression also reveals the toll that her enslavement has taken on her. Her left breast falls out from her loose garment, and seems taut beneath a tightly pulled rope, a passage that reminds us that the breasts, teeth, and other body parts of slaves were commonly examined before purchase. To my eyes, the bound African figure in the marble sculpture Why Born Enslaved! is completely different in mood and expression from the youthful, exuberant freed African woman depicted in the Fountain of the Observatory. The two sculptures may have been modeled after the same person in Carpeaux’s studio, but the spirit of each is completely different.

There is a bit more pathos in the terracotta version (fig. 3), purchased by the Metropolitan in 1997; the brows are still knitted but the eyes are softer and more imploring. The terracotta version is turned away from the main entrance into 521 and faces the Robert Lehman Collection, so that no matter which way the viewer enters the exhibition, they would be caught, arrested, by the individual expression of the figure (fig. 4).

One of the highlights of the exhibition is Edmonia Lewis’s marble sculpture entitled Forever Free (1867, fig. 5). It was a welcome addition to the exhibition as the only image of an emancipated couple by a Black artist, and one of only two works in the exhibition by a woman. According to the Metropolitan’s website, Forever Free had no previous exhibition history, an amazing fact considering that this sculpture has long appeared in US art history books. Her sculpture is a representation of a freed couple, the man standing with his broken chains lifted above his head with his right hand. His female companion (whose race is ambiguous) kneels and clasps her hands in a gesture of prayer. One might speculate that the couple depicted is Lewis’s own parents, as they were of mixed race. The only other known sculpture of an African American man in Lewis’s oeuvre was a portrait bust of James Peck Thomas, a former slave turned real estate agent (1874) who commissioned his portrait from Lewis. In this respect, Black figures were as rare in Lewis’s oeuvre as they were in Carpeaux’s. But in Lewis’s case, she was dependent on selling her work to a mostly white clientele.[4] Lewis was of African American and Ojibwe heritage. Carpeaux could easily sell an image of a Black woman to a white clientele, but Lewis had to tread that road softly, as she was a Black woman herself.

Continuing through the exhibition, Cordier’s bronze Bust of Seïd Enkess (1838, also called Saïd Abdallah, de la Tribu de Mayac, Royaume de Darfour; after 1850, Nègre de Timbouctou, fig. 6) and Bust of a Woman (1851, also called Nègresse des colonies; after 1857, Vénus Africaine, fig. 7), borrowed from the Art Institute of Chicago, and his Woman from the French Colonies (1861, also called La Capresse des Colonies, fig. 8) figure prominently. Today considered primarily ethnographic, Cordier’s sculptures now seem, as James Smalls notes in his catalogue essay, to “legitimate the idea of colonial expansion by promoting hierarchical thinking and proclaiming ‘universal fraternity’ while conceding that there were ‘physical differences’ between the races that defined intellect and character” (63). The onyx for this bust was extracted from French-occupied Algeria, which brings with it a host of additional problems. Nonetheless, the viewer who doesn’t read wall labels and exhibition catalogues will find it difficult not to be seduced by the intense beauty of this figure, whose expression so differs from Carpeaux’s Why Born Enslaved!. Cordier’s Woman from the French Colonies has a wistful expression, and her mouth looks to be just about to raise into a smile.

Artworks from the eighteenth century are also featured in the exhibition. Josiah Wedgwood’s (1730–95) Antislavery Medallion (ca. 1787, fig. 9), made in his signature jasperware, includes the famous phrase “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?,” establishing that it was made for the abolitionist market. It was the official seal of the London-based Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. The exhibition, however, takes issue with the position of the male slave figure, enchained and kneeling in a position that references the figure’s servitude. As Nelson notes in her catalogue essay “Sculpting about Slavery in the Second Empire,” it was “impossible to picture the liberation of Blackness without seeing simultaneous scenes of subjection” (46). However, it is not clear what the alternatives for Wedgwood (and the original designer William Hackwood [1757–1839]) would have been at the time to show a person in an enslaved situation; there are only so many visual solutions to this problem. The iconography of slavery always included some reference to bondage; the broken chains always a symbol of freedom from said bondage. Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia (first illustrated edition, 1603) explains that images of servitude should include (typically) a young girl in a short, white gown, with a yoke upon her shoulders, and with her hair disheveled (which would denote that he or she who must work for others neglects him or herself). The yoke or shackle with chains is the most essential symbol of servitude. Could the artists have removed the image of the chains and retained the clarity of the artwork’s message that it was about slavery specifically, and not just acceptance of people of all races into one’s heart? Certainly, Wedgwood and Hackwood could have designed the figure as standing instead of kneeling, but the point of the question the figure is asking (“Am I not a man and a brother?”) is that he is imploring the viewer, begging them in fact, to see him as a man and a brother. A comparison with Lewis’s male figure is unfair—Wedgwood’s man is still in a position of servitude. Lewis’s man has already been freed. I am much less suspicious of this medallion meant to be worn by a person who questions slavery than I am of a cologne bottle engraved with an antislavery image (ca. 1830, fig. 10) that also appears in the exhibition. These items, to me, seem to not be made for the same audience, or for the same type of collector of images of slavery.

Works from the period when France first abolished slavery are also included in the exhibition. One example is a hard-paste biscuit work entitled Porcelain Group of a Free Man and Woman (also called Les noirs libres, fig. 11) from 1794 by Louis Simon Boizot (1743–1809), which like Carpeaux’s sculpture, curiously, included an inscription: MOI EGALE A TOI. MOI LIBRE AUSSI (Me equal to you. Me free also). This is not proper French, but a type of patois (pejoratively referred to as “petit nègre”) spoken by colonized peoples. The couple sits rather than kneels, and the male figure points to his Phrygian cap, a symbol of his liberation. His female companion is topless for no reason, a common sexualization of a female figure and the only visual aspect of the sculpture that weakens it.

Also included in the exhibition were two small works by Jean Antoine Houdon (1741–1828), Head of a Woman (ca. 1781, fig. 12) and Bust of a Woman (1794 or later, fig. 13). These works are said to have been based on a fountain group by Houdon depicting a white female bather made in marble accompanied by a black female servant cast in lead.[5] Though the fountain was destroyed during the French Revolution, the white bather survives and is part of the Metropolitan’s collection (1782, acc. no. 14.40.673), but the lead figure of the Black servant did not survive, perhaps melted down for other uses, as commonly happened, especially during times of civil strife and war.[6] The tiny maquette of the Black figure owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art includes an inscription: “RENDUE A LA LIBERTE / ET A L’EGALITE / PAR LA CONVENTION NATIONALE / LE 16 PLUVIOSE / 2ME ANNEE / DE LA REPUBLIQUE FRANCAISE / UNE ET INDIVISIBLE” (Returned to Freedom / And Equality / By the National Convention / The 16th of Pluvoise / 2nd Year of the Republic). Once again, we see an inscription, phrase, or statement on a sculpture depicting a Black figure, used to establish the ideological position of the maker, and by extension, the purchaser of the artwork. According to wall text and to Adrienne L. Child’s essay in the exhibition’s catalogue, the only remaining references to the lead sculpture of the Black servant are the plaster study in the exhibition (fig. 12); a tiny work entitled Bust of a Woman (fig. 13), and a drawing of the fountain by Pierre-Antoine Mongin (1782–95) pictured in her essay. This omits Houdon’s full-scale Bust of a Woman at the Musée Nissim de Camondo in Paris, out on public view since the museum opened in 1936 (fig. 14). Cast by Pierre-Philippe Thomire (likely one of Houdon’s own founders), it bears the same inscription as the Metropolitan’s maquette. Unfortunately, it would not have been loaned to the Metropolitan’s exhibition, as the Musée Nissim de Camondo does not loan out its collection.

Finally, there are the two contemporary artworks, Kehinde Wiley’s After La Négresse, 1872 (2007, fig. 15) and Kara Walker’s Negress (2017, fig. 16). Wiley’s bust is set in a case alongside a plaster and paint version of Why Born Enslaved!, borrowed from the Brooklyn Museum. Instead of rope, Wiley’s young black male athlete wears a Los Angeles Lakers jersey as a contemporary symbol of exploitation. Size and different media aside, this was an excellent comparison and a very modern take on Carpeaux’s sculpture (fig. 17). The word “Lakers” crosses the young man’s chest like the ropes that cross Carpeaux’s enslaved woman, and we are reminded that US sports teams have “owners,” and that players are bought, sold, and traded. Walker’s Negress was placed on a very low base in a corner, lit only by a tiny spotlight. A cast of Why Born Enslaved! in plaster, Negress is what Caitlin Meehye Beach calls in her catalogue essay “a ghostly inverse of the bust” (99). While it is somewhat less impressive than the bust by Wiley, in part due to its placement on a low base near the floor in a corner, it acts as a reminder of Walker’s 2014 installation, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, which was made with the very substance (sugar) that enslaved people were forced to produce for so long.

The accompanying catalogue for the exhibition includes a preface by Sarah E. Lawrence, a poem entitled “In the Gallery” by guest curator Wendy S. Walters, an introduction written by Walters and Elyse Nelson, and six scholarly essays. The introduction suggests a possible model for Why Born Enslaved!. Louise Kuling (ca. 1829–n.d.) was a free woman from Norfolk, Virginia who came to France with a Frenchman named Captain (or Commander) Louvet (17, 83). She was photographed by Jacques-Philippe Potteau (1807–76) as part of an ethnographic portrait series for the Collection Anthropologique du Musée (Muséum) de Paris in 1864. However, no text-based evidence has been found to establish a connection between Kuling and Carpeaux. Certainly it is tempting to place a name on the woman who posed for Why Born Enslaved!, to give the figure in the sculpture, though not a portrait, a sense of personhood. Walters gives her a voice in her thoughtful poem mentioned earlier. But one can get into dangerous territory by suggesting possible models without any concrete evidence to support the claim. According to the metadata in the exhibition, the descendants of Cordier themselves claim that the model for Woman from the French Colonies and Carpeaux’s Why Born Enslaved! were the same person; the Metropolitan stakes a claim for Kuling. But there is little evidence, and this sort of conjecture does little for the field of art history, even if it gives the public a much desired name.

There are also incorrect statements in the catalogue. Childs’s essay claims, for example, that John Quincy Adams Ward’s The Freedman (modeled 1863, cast 1891, fig. 18) is “the first sculpture of a Black man in American art” (33), but this overlooks John Rogers’s The Slave Auction, made in 1859 and depicting a man, woman, and child on the auction block (fig. 19). The sculpture could have been borrowed for the exhibition from the New-York Historical Society, located just across Central Park, for this exhibition and added to the catalogue and conversation. Additionally, Karen Lemmey established more than sixteen years ago that Henry Kirke Brown’s (1814–86) relief on the monument to DeWitt Clinton in Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, from 1853, includes an African American figure in the front panel.[7]

Iris Moon’s “White Fragility: Abolitionist Porcelain in Revolutionary France,” discusses Louis Simon Boizot’s (1743–1809) attempt to recreate Wedgwood’s “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” for a French audience. After only eighteen examples were made in hard-paste biscuit porcelain, the production run was stopped by Charles Claude de Flahaut, the Comte d’Angiviller (1730–1809), for fear that if any examples reached the hands of the oppressed, they might revolt (36). Moon points out that commercial interests of powerful merchants and farmers made attempts at a strong abolitionist movement in France a challenge (38). Unlike in Carpeaux’s case, there is a bit more evidence to suggest that Boizot was an abolitionist: other sculptures, such as his La Nature (1794; not in the exhibition, but in the catalogue, 40), depicted an allegorical figure of nature offering charity of breast to two children, one white and one black.

Elyse Nelson’s essay, “Sculpting About Slavery in the Second Empire,” and James Smalls’s essay, “Dressing Up/Stripping Down: Ethnographic Sculpture as Colonizing Act,” both challenged the assumed abolitionist leanings of Carpeaux and Cordier, the foremost ethnographic sculptor of the period. According to Nelson, Carpeaux made no known statements regarding abolition, even though Why Born Enslaved! was always seen as his visual condemnation of slavery. Nelson notes that Carpeaux “profited from the resurgence of antislavery sentiment in abolition’s wake, three years after emancipation” (51). This rings true, and to make matters worse, Carpeaux was in financial trouble at the time, so he needed a marketable sculpture that would have popular appeal. Smalls, in his contribution to the catalogue, equates ethnographic sculpture with “a literal and figurative act of colonialism, part and parcel of France’s enterprise of colonial expansion and its attempts at cultural and national definition and influence” (62). Smalls makes a convincing argument that Cordier positioned himself as the greatest interpreter of anthropology and ethnography in France and cites from Cordier’s 1862 address to the Anthropological Society of France in which he states that, in his practice, after “seizing the common characteristics of the race that I want to reproduce . . . I then conceive of an ideal or rather a type for each of these characteristics” (69). But Smalls does not mention another quotation from the same address, in which Cordier famously noted that “beauty does not belong to a single, privileged race, I have promoted throughout the world of art the idea that beauty is everywhere. Every race has its own beauty, which differs from that of others. The most beautiful black person is not the one who looks most like us.”[8] Cordier had his failings, but he attempted to separate himself from the typical Eurocentric view of the world and promote the beauty of those whom he depicted. This ambivalence and complexity is missing in the catalogue’s account of him.

Walters’s other essay in the catalogue, entitled “Presumptions on the Figure, Given the Absences,” points out that some critics of Carpeaux’s Why Born Enslaved! did not like the inscription on the base. The critic Arthur Baignères thought the inscription should be “rubbed away” (78); another critic, Cl. Suty, seems to have been insulted by the inscription, as if the answer or response to Carpeaux’s inscription is obvious (78–79). In both cases, it seems clear that Carpeaux’s inscription touched a nerve. Evidently for these critics it was fine to produce a violent image of an enslaved woman in bondage in France, but the artist should not dare suggest that the viewer is implicated in her situation, which is what Carpeaux’s inscription does. The answer or response to Carpeaux’s declarative inscription “Why Born Enslaved!” is not that the woman is enslaved because she is Black; being Black is just the natural condition of her existence. The answer is that the woman was born enslaved because whites enslaved her. No other response to the inscription is logical. And, therefore, the white viewer of Why Born Enslaved! (then and now) must come to terms with their own role in the history of enslavement, both before the sculpture’s creation in 1868 and thereafter. Whether or not this was Carpeaux’s intention with the inscription, it is the result. The inscription disturbs the comfortable, as it should, and as Walters’s essay suggests it did that at the time.

The final essay in the catalogue, Caitlin Meehye Beach’s “Reproducing and Refusing Carpeaux,” discusses the contemporary artworks in the exhibition by Wiley and Walker, discussed above. A chronology compiled by Rachel Hunter Himes gathers all the important dates from the essays into a well-organized list. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s (1811–96) 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin is mentioned in the chronology, but not the fact that Stowe was given a gift by admirers in Boston of the English-French artist Charles Cumberworth’s (1811–53) sculpture entitled African Woman at the Fountain (1846, also called Mary Returning from the Fountain, from Paul et Virginie, fig. 20) in January of 1853. It was, as noted by an anonymous contributor in the Buffalo Morning Express, “a beautiful specimen of the noblest form of art and standing as a mute but expressive and powerful pleader in [sic] behalf of human brotherhood.”[9] It might have made for an interesting foil to Carpeaux’s Why Born Enslaved! in the exhibition if it could have been borrowed from the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford, Connecticut.

There is no discussion of the format of the works by Carpeaux and Cordier in the catalogue. The full scale, life-sized bust format was always used in Western art for figures of emotive and/or political power, typically reserved for only the most important figures in history and society. One can equate it with the large-scale canvas in the nineteenth century: one reason that Gustave Courbet’s (1819–77) Stone Breakers (1849–50, unlocated or destroyed) caused a scandal was because the large-scale canvas was reserved for the depictions of the rich, or the powerful, or gods, or important historical events. It was not the format in which the poor had previously been depicted or glorified. The poor, or people of color, or people from diverse nations outside of France, were just not placed on a sculpted pedestal in life size, literally and figuratively. What a shock it must have been to the typical racist to see Seïd Enkess, realistically or idealistically, depicted in such a loaded format, a position, since ancient times, of glory and power.

Also omitted from the exhibition and catalogue are the ugly racist caricatures of Africans that were circulating at the same time. However mixed the motives of Carpeaux, Cordier, Houdon, Lewis, and Wedgwood may have been, they sought to insert Africans into the Western canon of beauty and tell their story of struggle. Including overtly racist imagery in an exhibition is complicated, and perhaps it would have been impossible for this one: it requires contextual information, warning signs, perhaps even a separate room. One danger, however, of removing such racist imagery is that it is forgotten; a more minor consequence is that Carpeaux’s and Cordier’s imagery cannot be judged against the spectrum of depictions of race.

The exhibition and the catalogue did provoke thoughts about human rights abuses and enslavement in our own times, as there are so many parallels between the past as discussed in this material and us. Just as the French addiction to coffee and sugar was connected to enslavement and murder, so too is our addiction to smartphones, the internet, and oil linked to similar atrocities. As of June 2021, over 160 million children (almost one in every ten children worldwide) are working as child laborers in unsavory conditions. Over 40,000 Congolese children are laboring right now to hand pick the toxic cobalt that runs the cell phone on which you might be reading this review.[10] As of October 2021, forty percent of all sex trafficking victims are recruited online.[11] Yet, most people are so addicted to their phones that they check them approximately ninety-six times per day, or once every ten minutes.[12] According to Robert Cowan’s book Teaching Double Negatives (2018), “over twenty-seven million people worldwide are enslaved, half of whom are children; this is more than double the number enslaved during the entire Trans-Atlantic Trade.”[13] And yet, many of us think ourselves to be against human rights abuses such as these; many of us would gladly click “like” on a social media post about promoting human rights. But who will know of our beliefs in the future, or where our sympathies may have lain, when they find that the innards of all our old cellphones will have completely contaminated their groundwater? Or that we shrugged at the fact that young people are recruited on our precious internet to be raped? Or that at a time when slavery is illegal in every country on Earth, evidence that it still exists widely and globally is an open fact? The fictions of emancipation continue, indeed.

If in their understanding of the history of nineteenth-century sculpture, the exhibition and catalogue fell short, Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast was still an essential exhibition: it presented objects in a manner that allowed for serious critical thinking about how race and freedom were represented in the nineteenth century. The exhibition also included, at its end, a space for viewers to have a voice and consider questions that appeared throughout the exhibition, such as “What is representation?”; “What is abolition?”; “Who narrates history?”; and “What is the legacy of the Black figure in Western art?”; cards and pencils allowed viewers to compose answers to these essential questions (fig. 21). The strength of both the exhibition and catalogue are in the discussions of race and in the rethinking of images of emancipation that continued to work within the language and iconography of subjugation. I had always accepted Carpeaux’s Why Born Enslaved! to be proof of his political leanings; this exhibition and its catalogue demonstrate that the question is not so simple, and they will change my teaching of these objects in the future. We are also in a moment where many museums and cultural institutions are making a choice to bury works of art with difficult subject matter in the bowels of their storage facilities, never to see the light of the gallery again in our lifetimes. It is commendable that the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the curators and scholars who contributed to this exhibition, decided to instead educate the public about the theme of slavery and the problematic issues surrounding abolitionist imagery in particular. Hiding or destroying an object that contains difficult subject matter does not, and will never, erase the violent history with which the objects are connected. It is best to face that history with intelligence, confront the artworks head-on, and finally come to terms with who we were, and who we are, as it is reflected back to us in art.

Notes

I am grateful to everyone whose comments and suggestions helped me to clarify my arguments here, specifically Brian Edward Hack; Patricia Mainardi; Maboula Soumahoro; the Kingsborough Community College Writing Circle, Fall 2022 semester: Robert Cowan, Maria G. Hernandez, and Alyse Keller; and the editorial team at Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, especially David O’Brien and Kirstin Gotway.

[1] While the term “Négresse” would not be used in France today to refer to a Black woman, in the nineteenth century the term would not have been considered pejorative. I thank Maboula Soumahoro for clarifying this point with me.

[2] In the Salon of 1869, Négresse was exhibited as number 3283; Portrait of Charles Garnier was number 3284. Carpeaux was by this time “hors concours” (outside of the competition) and his works were no longer subjected to jury scrutiny. Therefore, Négresse was guaranteed to be accepted into the exhibition. See “Salon of 1869,” in Catalogue of the Paris Salons (New York: Garland Publishing, 1977), 459, https://babel.hathitrust.org/.

[3] The Emancipation Proclamation was issued on September 22, 1862 and was set to begin on January 1, 1863. It was passed as the 13th Amendment by the United States Senate in 1864 and by the House of Representatives in 1865.

[4] Antje Anderson, “Forever Free,” Discovering Edmonia Lewis: A Black Female Sculptor in the Nineteenth Century, https://edmonialewis.org/.

[5] https://www.metmuseum.org/.

[6] This is especially true of lead, which has a low melting point of only 621.5 degrees Fahrenheit. Bronze, by contrast, melts at 1675.0 degrees Fahrenheit.

[7] Lemmey discusses this research in Celia Peters, “African-American depiction is monumental,” Baltimore Sun, April 2, 2006, https://www.baltimoresun.com/.

[8] “Le beau n’est pas propre à une race privilégiée, j’ai émis dans le monde artistique l’idée de l’ubiquité du beau. Toute race a sa beauté qui diffère de celle des autres races. Le plus beau nègre n’est pas celui qui nous ressemble le plus.” http://www.muma-lehavre.fr/.

[9] Buffalo Morning Express, Friday, January 28, 1853.

[10] Feza Tabassum Azmi, “The Little Hands of Labour Behind Your Smartphone,” The Wire, June 16, 2021, https://thewire.in/. See also Jason Mitchell, “Will child labour concerns deny the DRC its cobalt riches?,” Investment Monitor, July 22, 2021, https://www.investmentmonitor.ai/.

[11] “Good Use and Abuse: The Role of Technology in Human Trafficking,” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, https://www.unodc.org/.

[12] Jack Flynn, “20 Vital Smartphone Usage Statistics [2023],” Zippia, October, 20, 2022, https://www.zippia.com/.

[13] Robert Cowan, Teaching Double Negatives: Disadvantage and Dissent at Community College (New York: Peter Lang, 2018), 92. I wish to especially thank Robert Cowan for reading this review before its publication, and for sharing his research on teaching about slavery with me for this review. Cowan’s study also notes that the price of a slave in 1863 in today’s dollars would be $40,000, but also that the price of a contemporary slave today is a mere $90 in today’s dollars (see Teaching Double Negatives, page 94).