Léon Bonvin: Drawn to the Everyday, 1834–1866 and Dessins français du XIXe siècle (Nineteenth-century French Drawings)

Reviewed by Mary G. MortonMary G. Morton

Curator and Head of Department, French Paintings

National Gallery of Art

Email the author: m-morton[at]nga.gov

Citation: Mary G. Morton, exhibition review of Léon Bonvin: Drawn to the Everyday, 1834–1866 and Dessins français du XIXe siècle (Nineteenth-century French Drawings), Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.1.16.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Léon Bonvin: Drawn to the Everyday, 1834–1866

Fondation Custodia, Paris

October 8, 2022—January 8, 2023

Catalogue:

Maude Guichané and Gabriel P. Weisberg, eds.,

Léon Bonvin: Drawn to the Everyday, 1834–1866.

Paris: Fondation Custodia, 2022.

304 pp.; 152 color and 35 b&w illus.; appendices; bibliography; entries; exhibitions.

€35 (hardcover, French and English)

ISBN: 978–958–323–400

Dessins français du XIXe siècle (Nineteenth-century French Drawings)

Fondation Custodia, Paris

October 8, 2022–January 8, 2023

Catalogue:

Rhea Sylvia Blok, Antoine Cortes, Marie-Noëlle Grison, Maude Guichané, Laurence Lhinares, Ger Luijten, Marie-Claire Nathan, Juliette Parmentier-Courreau,

Dessins français du XIXe siècle.

Paris: Fondation Custodia, 2022.

352 pp.; 145 color illus.; catalogue raisonné with technical descriptions and notes; bibliography; exhibitions.

€40 (hardcover, French)

ISBN 978–2–958–323–424

Not everyone has on their Parisian radar the extraordinary institution that is the Fondation Custodia, housed in an eighteenth-century hôtel particulier just off the Boulevard St. Germain where it meets the quai d’Orsay and the Assemblée Nationale (fig. 1). Established in 1947 by the Dutch art historian and collector Frits Lugt, the institution holds an impressive collection of works on paper, artists’ manuscripts, rare books, and paintings, including an amazing collection of over 250 plein-air oil sketches from the late eighteenth through nineteenth centuries (fig. 2). The latter repository was built by the foundation’s director since 2010, Ger Luijten, working closely with dealers and experts, with an impassioned focus and zealous energy that was impressive to behold. Luijten also consistently mounted carefully curated and well-catalogued exhibitions, organized research projects, hosted scholars, tastefully renovated and expanded the institution’s buildings inside and out, and managed a wildly busy staff with wit, warmth, and generosity. It is fair to say that he inspired every person who crossed his path with his infectious curiosity and deep love of art and scholarship. His sudden death on December 19, 2022, was a terrible blow for the international art world.

Luijten’s final exhibition projects were characteristically rich and revelatory, as well as deeply moving in that intimate, poetic mode of very fine works on paper. The two exhibitions, Léon Bonvin: Drawn to the Everyday, 1834–1866 and Dessins français du XIXe siècle formed a graceful partnership during their run from October 8, 2022 to January 8, 2023, the former occupying the cozy subterranean galleries, and the latter in the gorgeous sequence of rooms on the second floor.

Reflecting the centrality of acquisitions in generating art historical research and knowledge at the Custodia, the Bonvin exhibition was inspired by purchases, starting in 2006, of several drawings, a watercolor, his only known oil painting, his watercolor box, and several photographs. The younger brother of the realist artist François Bonvin, Léon was not himself a professional artist, but rather an innkeeper struggling daily to make ends meet for himself and his family. Few documents pertaining to his life remain, and he died tragically early at the age of thirty-two.[1] His first museum monograph was organized by Gabriel Weisberg in 1980 for Cleveland and Baltimore, and included thirty-three sheets, with a call for further research to enhance the artist’s known oeuvre, and, eventually, a catalogue raisonné.[2] The Custodia catalogue fulfills that mission, with Weisberg writing the introductory essay.

Bonvin received virtually no critical attention as an artist during his short life, but within months of his death, a melancholic throughline established itself in reviews of his life and work. Determining the theme was his suicide on January 29, 1866. A day after his unsuccessful attempt to sell some of his work in a Parisian dealer’s shop, he hung himself from a tree in the Meudon forest near the family inn on the outskirts of the capital city. François organized a fundraising sale to support Léon’s widow and three “orphelins” emphasizing in the call for participation the callousness of the art market in rejecting this authentic talent. The list of contributors to the sale at Drouot in May 1866 is a veritable who’s who of 1860s realist painting and printmaking, including Félix Bracquemond, Jules Breton, Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet, Charles-François Daubigny, Johan Barthold Jongkind, Jules Joseph Augustin Laurens, Ernest Meissonier, Claude Monet, Felix Nadar, Théodule Ribot, Antoine Vollon, Maxime Lalanne, and of course François Bonvin, a total of eighty-eight participants.[3]

While François Bonvin lived in Paris and moved within this artistic milieu, we do not know how many of these artists his younger half-brother might have known personally. Seventeen years older, François had left his father’s home by the time Léon was growing up, one of nine children from his father’s second wife. François claimed credit later in life for advising the young aspiring artist and for teaching him “a few things.”[4] Léon enrolled in the state-sponsored École du Dessin (drawing academy) in Paris for an undetermined time, and probably had access to the booming trade in reproductive art prints, if not the collections of the Louvre, but there is little documentation confirming a structured program of training.[5]

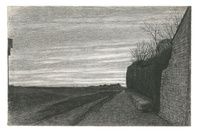

The aesthetically arresting nature of Léon’s production, sixty examples of which were on view in the Custodia’s galleries, feels like something of a miracle. Whether inspired by contact with artistic precedents or innately talented (likely both), Bonvin combined a distinctly personal sensibility with incisive observational skills, training his gaze on his immediate social circle and environment. An early charcoal, The Plain at Vaugirard (1856, fig. 3) shows a mastery of the medium in recording the streaky dawn/dusk sky, the masonry walls, and the finely drawn winter branches. The range of textures and shapes and the sense of space, and in particular the framing of the view between the curving wall and a thin band of a building’s edge are striking. This sheet, alongside two intimate scenes of a woman at work in the dim light of the inn’s kitchen and common room, conjure Georges Seurat’s black chalk drawings in their formal simplification and dramatic use of backlight, shadow, and the luminosity of the white paper.

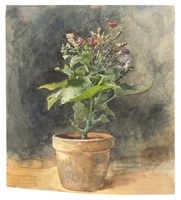

By 1855, Bonvin was experimenting with watercolor, a notoriously difficult medium to control that he fully apprehended over the following decade. Early efforts involved flower still lifes, informal arrangements of seasonal blooms and grasses that Bonvin culled from his garden and environs. In the early 1860s, the compositions became more complex as slim glass and ceramic vases struggle to hold the floral profusion: chrysanthemums, white stocks, nettles, daisies, and dahlias. Bouquet of Lilacs (1862) features pink and white blooms and large shiny leaves, but of equal interest is the pattern of stems submerged in water seen through the distorting curve of the glass vase, as well as the reflection of the window and perhaps of the artist’s silhouette, in the bulging glass (fig. 4). In works like Pot of Flowers (1861), he combines his impressive botanical accuracy with loose washes suggesting light and space (fig. 5). Flower still lifes remained his dominant motif—they likely engaged the artist with their infinite range of color, shape, and texture, and perhaps as importantly, they were relatively marketable. Indeed, in 1863, the Baltimore collector William Walters commissioned through his Paris agent George Lucas a dozen flower compositions, a crucial financial lifeline for the destitute innkeeper (65–83).

Lucas was in fact the most active dealer/agent of Bonvin’s work, handling some two-thirds of the artist’s total oeuvre, the majority of which, fifty-seven, went to Walters’s home on Mount Vernon Place in Baltimore. Walters and Lucas clearly recognized the young artist’s genius. They acquired works at the fundraising sale following Bonvin’s death and continued to buy sheets over the following decades.[6] In 1885, they commissioned the critic Philippe Burty to write an essay on Bonvin for Harper’s Weekly, including high quality, wood-engraved reproductions of nine watercolors in the article, the subject of Jo Briggs’s catalogue essay. In the exhibition, a copy of the Harper’s essay’s first page with the print after Bonvin’s magical Goldfinches (1864) illustrating the adjacent page was on view, and the prints are reproduced in an appendix of the exhibition catalogue (fig. 6).

Walters also bought Bonvin’s kitchen still lifes, made mostly in 1864 and 1865, depicting table tops carefully arranged with white cloth, plates, and glass bottles, and distinguishing fruits and vegetables including a pomegranate, radishes, lettuce heads, scallions, fish, and parsley greens. Still Life with Celery (1865) presents the ingredients for a salad: oil and vinegar bottles in a holder, a ceramic bowl with tossing spoons, shallots, and enormous celery stalks whose dirty, frazzled roots jut out into the viewer’s space, framed against the bleached white of the linen (fig. 7). Meticulous detail combines with subtle color harmonies and rhythmically placed objects to create a painting that approximates the pleasures of a Chardin. Indeed, Bonvin may have had the eighteenth-century master in mind given the revival of interest at the time in his work. The remarkable acuity of vision in works like this one has been attributed by Weisberg to Bonvin’s “innocent eye” able to “discern the truth in nature,” and Maude Guichané discusses Léon’s “intuitive” versus François’s “erudite” realism in her catalogue text.[7] The artistic freedom of production outside the academy is a subtheme here, one that would move to the dramatic center of art historiography with the advent of impressionism in the 1870s.

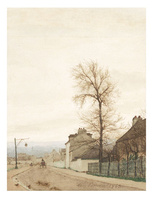

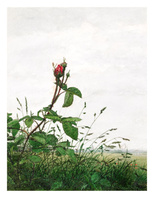

The most original and absorbing works by Bonvin’s hand are perhaps the series of outdoor plant studies placed within their native landscape. The artist moved out into the broad, barren planes of Vaugirard, now the southern part of the 15th arrondissement in Paris. Not yet fully integrated into the city but no longer in its pristine “natural” state, this suburban land emits a sense of melancholy. Road in the Plain of Vaugirard (1863, fig. 8) sets the scene, the road to the city freshly cut, a tall leafless tree in the Bonvin garden at the right balanced by a streetlight, strangely out of place, at left. Rose Bud in Front of a Landscape (1863, fig. 9), Feverfew in Front of a Landscape, Issy-les-Moulineaux (?) (1863), and Blackthorn (?) in Front of a Landscape at Sunset (1864) feature winding branches, leaves, and blooms backlit by vaporous skies, with vaguely delineated buildings—houses, church spires, perhaps the dome of the Pantheon—in the distance. Winter views of spikey wild eryngium and thistle against the milky light of cold-weather skies are particularly poignant (fig. 10). In comparison, the lush summer scenes of 1865 lack the graphic sharpness and fine filigree of frozen leafless boughs, the sense of atmosphere, the desolate ambiance of suburban “nature” that is so affecting.

Emerging from the Custodia’s downstairs galleries, filled with a marvelous sense of discovery—for, apart from The Walters’s staff and visitors and experts like Weisberg, who has seen more than a sheet or two of Bonvin’s work before—the wonderment continued on the second floor with Dessins français du XIXe siècle, a display of 140 works on paper out of some 1,800 total in the Custodia collection (fig. 11). During his collecting career, from roughly 1914 to his death in 1970, Frits Lugt focused mainly on art from classical antiquity to the second half of the eighteenth century, avoiding nineteenth-century art as too recent for proper critical discernment.[8] In bringing the collection chronologically forward over the last fifty years, Custodia directors generally adhered to Lugt’s guiding taste, favoring landscapes, human figures, and portraiture as opposed to studies for neoclassical history paintings (preparatory works with an explicit end goal versus independent studies). Building a first-rate collection requires working closely with dealers, and Luijten credits in particular the Custodia’s relationship with the great Chantal Kiener, an expert in nineteenth-century art who ran a gallery in Paris for years with her partner Jacques Fischer.

The exhibition intended to foreground lesser known (and virtually unknown) artists who, in moments of inspiration, produced brilliant sheets in graphite, charcoal, gouache, and watercolor. In the preface of the catalogue, Luijten explained his goal to have the display and the catalogue, as well as the online publication of the entire Custodia holdings in this area, serve as a reference not only for experts and scholars but also for burgeoning collectors. Rather than a survey of nineteenth-century draftsmanship, then, the show featured diversity and range, including works by star artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Eugène Delacroix, Corot, and Rosa Bonheur alongside those of Achille Benouville, Eugène Buttera, and Lionel Le Couteux, and of virtually unknown artists like Caroline de Fontenay and Charles Eustache. Standouts for me included a drapery study by a female artist named Pauline Auzou who entered the studio (open to women) of Jean-Baptiste Regnault in 1793 (fig. 12). In black and white chalk with a deft use of stumping, she made of this classic academic exercise a poem-in-sfumato. An Ingresque line-drawing by Pierre-Maximilien Delafontaine of his wife and her close friend sitting side by side, the fingers of their hands casually entwined, captures a lovely moment of female intimacy. An undated work by Corot’s friend and painting partner in Italy, Caruelle d’Aligny, traces the contours of the hills around Subiaco, alternately light-struck and shadowed from passing clouds. He expertly deploys the clean, white paper as much as diluted brown washes and fine graphite lines to describe the scene. Jules Didier’s view of the gardens of the Villa d’Este in Tivoli from March 1859 is an intriguing line-up of, from right to left, a gnarled tree trunk, figural garden sculpture, ancient stone plinths, fountain basins, and a series of grand trees splintered by age (fig. 13).

More favorites include Paul Gavarni’s “croquis pittoresque” of a door wedged into a hillside in Montmartre in 1834 (fig. 14) and Jongkind’s view a decade later of the same neighborhood’s combination of undeveloped land-heaps and densely clustered, chimney-smoking homes; Gustave Doré’s vertically oriented, quasi-symbolist slice of the densely packed Westbridge forest in Sussex in 1879; Léon Coignet’s quiet whisper of a moonscape on the coast, waves rolling in while the scene shimmers in and out of legibility (fig. 15); a haunting self-portrait in charcoal by the Nabi artist Ker Xavier Roussel; and James Tissot’s witty vestiare (changing rooms), jammed with silk top hats and overcoats lined up on hooks like a schoolboys’ locker room (fig. 16). The chronological conclusion to the show is a pair of rustic old slippers in black pencil and brown and gray watercolor by Albert Besnard. Placed side by side, slightly askew, they look like they have just been vacated, a poignant portrait of absence (fig. 17).

The exhibition was to be accompanied by a digital-only catalogue, but the support of several donors and designers allowed it to be printed, and it is always a pleasure to leaf through a volume that recalls a viewing experience and add a book to one’s reference library. At the same time, the entire collection of nineteenth-century drawings has been published on the website, where better reproductions than were possible in the print publication can be found, along with mapping features, links to provenance information, and of course tabs on research around assigned Lugt numbers. A seemingly infinite series of rabbit holes is on offer in the form of “subject/iconclass” categories through which users can click through to amassed images within rubrics like “rocks” or “landscapes in the temperate zone,” “mid-day meal—lunch—outdoors,” “baldness,” and “love personified.”

Among the many brilliant aspects of Ger Luijten was his combination of reverence for “old school” art history (the seminal work of the discipline dating back to its nineteenth-century origins of discovering, conserving, and cataloguing for the future the art of the past through connoisseurship and archival research) with excitement about the spectacular possibilities for art history of new technology and the digital humanities. As always, Luijten had big plans for the future involving more and better modes of recording and interpreting old art and sharing it with as many people as possible in the most enticing and accessible way. His expansive lust for life and art was essentially social. On experiencing a glorious drawing or oil sketch on the market, a passage from a favorite poem, a familiar rock song from the 1960s, a newly flowering tree on the city street, one sensed that his pleasure was complete only once it was shared. His spirit lives on in all those whose lives he touched, and through the unfailingly excellent projects at the Fondation Custodia (fig. 18).

Notes

[1] Bonvin’s marriage and death certificates are transcribed in appendix II of the exhibition catalogue, 270–73.

[2] Gabriel P. Weisberg, The Drawings and Water Colors of Leon Bonvin (Bloomington, Indiana: Cleveland Museum of Art in cooperation with Indiana University Press, 1980).

[3] The catalogue of the sale is transcribed from The Walters’s copy in appendix V of the exhibition catalogue, 278–83.

[4] See the two letters written by François Bonvin to Philippe Burty while the critic was composing his Harper’s Weekly essay in 1884, reproduced, transcribed, and translated in the appendix of the exhibition catalogue, 274–77. See also Maude Guichané’s essay in the catalogue, “Léon and François Bonvin, an Artistic Kinship,” 84–95.

[5] For Ger Luijten’s views on Léon Bonvin’s familiarity with the contemporary art scene, see his essay in the catalogue, “Seeking Inspiration,” 41–48.

[6] Walters initially bound his Bonvins in green leather albums with a commissioned frontispiece which read “Near Paris,” before removing some for a special gallery devoted to Bonvin. See Jo Briggs, “Condemned to Sparkle: The Reception, Presentation, and Production of Léon Bonvin’s Floral Still Lifes,” The Oxford Art Journal 38, no.2, (2015): 247–62.

[7] Weisberg, 1980, 7; Guichane, 84–95.

[8] Ger Luijten, “Preface,” Dessins Français, iv–vi.