The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler by Margaret F. MacDonald with Charles Brock, Patricia de Montfort, Joanna Dunn, Grischka Petri, Aileen Ribeiro and Joyce Townsend

Reviewed by Deborah CherryDeborah Cherry

Professor of Art History and Theory

Central Saint Martins

University of the Arts London

Email the author: deborah.cherry[at]arts.ac.uk

Citation: Deborah Cherry, book review of The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler by Margaret F. MacDonald with Charles Brock, Patricia de Montfort, Joanna Dunn, Grischka Petri, Aileen Ribeiro and Joyce Townsend, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.1.6.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Margaret F. MacDonald with Charles Brock, Patricia de Montfort, Joanna Dunn, Grischka Petri, Aileen Ribeiro and Joyce Townsend

The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler.

New Haven: Yale University Press; Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art; and London: Royal Academy, 2020.

232 pp.; 170 color illus.; notes; appendix.

$50.00 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978–0300254501

Whistler and the Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan.

London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2022.

232 pp.; 170 color and 12 b&w illus.; notes; appendix.

£25.00 (paperback)

ISBN: 00 978–1–912520–87–9

“Seeing your ideas live on in the work of others.”[1] This wise warning from the Guerrilla Girls’s The Advantages of Being A Woman Artist may well apply to women models, especially she who was model, muse, and partner to a renowned male artist. A model’s appearance in art exposes her to hyper-visibility. Models don’t leave traces. Or do they? Models, after all, enact the main protagonists in modern figure painting. The possibility and extent of a model’s active input in the art that portrays her is intriguing.

The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler is the publication accompanying an exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London and the National Gallery of Art in Washington in 2022. The Preface explains: “The complex personal and artistic partnership between model and painter forms the underlying framework” for “an examination of Whistler’s images of Hiffernan and the cultural resonances surrounding them” (8). Although “the full extent and nature of their collaboration are not entirely clear” (12), The Woman in White makes an important acknowledgement of their “artistic partnership” (15). The exhibition and catalogue bring together paintings, drawings, and prints for which Joanna Hiffernan modelled, from James McNeill Whistler’s Wapping (1860–64) through works by Gustave Courbet.[2] At the center are three iconic artworks that “marked a turning point in [Whistler’s] career” (33): Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl (1861–63, 1872; fig. 1), Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl (1864, fig. 2), and Symphony in White, No. 3 (1865–67, fig. 3), in which Hiffernan is the figure on the left, shown with a well-chosen selection of figure paintings, studies, and landscapes by Whistler and many others.[3]

The project’s lead is Margaret MacDonald, the renowned Whistler scholar whose unrivalled and deep knowledge informs numerous publications about this artist; she is the author and co-author of three chapters. Four further chapters situate Whistler’s art in an extensive network of connections in art, literature, exhibition histories, and fashion. The Appendix provides documents, including Whistler’s letters with sketches of and discussions about ongoing work. In “Painting Joanna Hiffernan,” Joyce Townsend, senior conservation scientist at Tate, and Joanna Dunn, painting conservator at the National Gallery of Art, investigate Whistler’s artistic materials and painting techniques, drawing the reader deep into the materiality of the pictures and the complex processes of their making. Two chapters situate Whistler’s exhibitions within the cross-currents of public spectacle and critical opinion. While Patricia de Montfort examines the connections between Whistler’s art, Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White (serialized 1859–60), sensation culture, and literature, Grischka Petri considers “the public careers” of the Symphony paintings through their initial exposure, relative invisibility, and the new collectors and museums of the turn of the century (176). Aileen Ribeiro tracks trends in white attire in life and in art across high fashion, day wear, underwear, and studio accessories, linking the white dresses to artistic and mainstream style. Charles Brock’s “short history” discovers the long legacy of the first white painting up to the present. He perceptively argues that this painting of “a striking, red-haired woman, unidentified, with little or no social standing” that “flaunt[ed] basic rules of pictorial etiquette” offered a radical revision of the grand manner portrait (177–78).

The catalogue’s multitude of women in white showcases artistic elan in the rendition of white fabrics from the substantial to the diaphanous, arranged in generous swathes or fine pleats that testify to the breathtaking skills of the period’s needlewomen. Although Hiffernan is sketched once en negligée and is otherwise completely clothed, there is the familiar array of scantily-dressed women. Despite the dazzling range, for some there will be missed contenders. Jacques-Louis David’s Mme Récamier (1800, fig. 4, acquired by the Louvre in 1826) is surely the most famous portrait of a woman in white seated on a daybed. Alice Mackrell has flagged Whistler’s interest in Thomas Gainsborough whose “new following and emulation largely rested on his paintings of fashionable women in white gowns” (fig. 5).[4] His enthusiasm for “Gainsborough and our old loves” would surely have included Anthony van Dyck, inspirational as much for Symphony in White, No. 1 as to his eighteenth-century emulators.[5] In contemporary art, Lorna Simpson’s white shift photographs, Lorraine O’Grady’s “Woman in White” in Rivers: First Draft (1982–2015, fig. 6), Maud Sulter’s portrait of Bonnie Greer (2002),[6] and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s figure paintings are among many works by Black women artists to divert and completely re-invent the woman in white.

Including Eduoard Manet’s Eva Gonzalès (1870, fig. 7) would have been a game-changer. Showcased at London’s National Gallery this past winter, this portrait shows the artist, attired in a revivalist white evening gown, at her easel putting the finishing touches to a framed still-life. In-depth research, technical examination, and art historical analysis yield refreshing new insights on this much-debated portrayal, viewed here as Manet’s conscious positioning of his only pupil within the history of French art and the rococo revival.[7] Gonzalès was a talented and innovative painter of fashionable Paris and plein air landscapes (fig. 8), Emma Capron noting “in 1874 the theme of the theatre box was entirely novel in large-scale painting” (61). Curators Capron and Sarah Herring locate Manet’s portrait in a long line of (self-)representations of women artists from Angelika Kauffmann to Hazel Lavery, pictured at the easel with artist materials and dressed in white. These creative women in white are conspicuously absent from the publication under review.

Whistler’s paintings pose troubling questions worthy of deeper investigation, all centered around whiteness. Why did Whistler paint pictures of women in white, hardly a new artistic subject in 1861? Was he prompted by artistic rivalry or emulation, as suggested here? French critics situated Symphony in White, No. 1 within the European tradition; the white painting’s pedigree surely merits as much attention as its contemporaneous present and its putative futures.[8] Did Whistler just like showing off? He wrote to Henri Fantin-Latour in 1867 of “the piano, the White Girl, the Thames pictures—the seascapes . . . canvases produced by a nobody puffed up with pride at showing off his splendid gifts to other painters.”[9] A line in Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem “Brise marine” (1864), “Le vide papier que la blancheur défend,” proposes white as a concept, a protective carapace disturbed by marks that proclaim (the difficulties of) creative beginnings. Did Whistler relish the painterly challenge of painting white on white, as Jules-Antoine Castagnary suggested?[10] The second white painting was produced in the same year as Purple and Rose: The Lange Leizen of the Six Marks (1864) and Caprice in Purple and Gold: The Golden Screen (1864, fig. 9). Was Whistler interested in color theory, in variously testing its propositions?[11] Although he publicly stated that the first white painting “simply represents a girl dressed in white standing in front of a white curtain,”[12] color is not absent. Townsend and Dunn’s technical analysis—don’t miss their detailed notes—confirms that whiteness was a pictorial value achieved though process and relation, not an entity in itself. Symphony in White, No. 1 is slightly smaller than grand manner portraits and proportionally narrower (2:1 rather than 3:2), so accentuating the towering figure placed higher on the picture plane and the composition’s strong verticals. The diagonal pull of the animal skin with its flecked browns and greys, and the dropped pins of the scattered flowers and hem points triangulate the ground. On the much smaller canvas of the second white painting, bands and touches of color map its shallow geometry, complementing the spatial ambiguity created by the mirror and its reflections. In the close tones of the white paintings there is much that teases vision to question visibility. In Symphony in White, No. 1 a barely perceptible window is almost concealed by the curtain,[13] and at one stage Whistler painted “a sheer bodice over undergarments” (36). In the second, the fabric is transparent at the shoulders and semi-transparent in the sleeves. Of Symphony in White, No. 3 Whistler wrote to Alphonse Legros: “Jo in a very white linen dress, the same dress as the white girl earlier—the figure is the purest I have done—charming head. The body, legs, etc., can be seen perfectly through the dress.”[14] Supple and adaptable, lightweight and washable, white muslin became, ca. 1775–1810, the fabric of choice for softly draped gowns that would inspire the white dresses in Whistler’s paintings, though Hiffernan’s torso and arms are never exposed. Fine muslin clings to the body, revealing a figure with neither corset nor crinoline and shaping the contours of the legs; a single layer barely skims the skin yet when draped in layers gives fullness and opacity. White cotton has a dirty history: pristine condition required hard work and harsh chemicals; its manufacture depended on slavery in the US South and British imperial exploitation, policy, and trade in South Asia.[15]

Much has been written elsewhere about what Aileen Tsui eloquently identifies as Whistler’s “titling tactics,” which she attributes to Whistler’s restless self-fashioning and attention-seeking.[16] Success in the volatile, highly competitive and intensively capitalized arena of contemporary art demanded skillful management by artists and gallerists alike. The “great sensation—for and against” (to quote Joanna Hiffernan) around Symphony in White, No. 1 testifies to the inauguration of the society of the spectacle in which an alliance with a run-away bestseller attracted maximum publicity. Titles are thresholds. They provide, as Jacques Derrida suggests, a necessary edge for a text. Like any border the title allows and delimits the text’s débordement, its interactions with other texts.[17] What then of the words in play? The phrase “little white girl” is multivalent, skidding into nineteenth-century discourses on race, childhood, and sexuality. White, as I suggest, overflowed with potential meanings. Youth, vulnerability, and immaturity are emphasized in the conjunction of little (diminutive, small in size or stature) and girl (a female child): in the 1860s the UK age of consent was 12.[18] However, when in 1862 Hiffernan asked George A. Lucas to “[r]emember me to your little girl,” she referred not to a female child but to an adult woman, Octavie-Josephine Macedo-Carvalho, née Marchand (1833–1909), the intimate companion of her addressee, then in her late twenties, nine years younger than Lucas.[19] There is much to be investigated about the potential agency of Whistler’s titles, as well as in the ways in which the titular character of Collins’s novel might have affected exhibition visitors. Anne Catherick, a vulnerable young woman whose dressing in white is a mark of her fragility, has certainly “slipped out of the critical conversation.”[20]

The Preface admits a decision to exclude “the intertwined issues of race, nationality, and the American Civil War,” continuing, “To do so would have required a substantial shift in emphasis” (8). Although the impact of the Civil War on the artist is disputed, Daniel Sutherland is in no doubt that it “significantly altered Whistler’s life.”[21] The white paintings and their “public careers” took place in tumultuous times: the Civil War, Reconstruction, and beyond; the violent suppression of the Morant Bay rebellion in the British colony of Jamaica (1865), which sparked contentious debate on the legacies of slavery and the status of Black citizens;[22] and the Chincha Islands War (1864–66), an “international squabble over bird shit” in the memorable words of Alexis Clark (37). In an outstanding essay that maps “the transoceanic ties between Confederate loss and South American victory,” Clark skilfully dissects Whistler’s privileged mobility and “the dark side of cosmopolitanism” to retrieve in his Valparaíso paintings (fig. 10) “the residue of imperialism, racism, and capitalism,” all too often, as she rightly notes, obscured by scholarship and aesthetics.[23] To situate Whistler and his art within these global frames is to acknowledge the highly contentious intersectional politics of race and ethnicity, gender and class that shaped modernity in Europe and the Americas, especially during the 1860s, a critical decade marked by intense racial conflict and the strengthening of scientific racism. Whistler retained close ties with the country of his birth, shifted his alliances from the Union to the Confederacy, and was racist in his behaviour and attitudes. In Symphony in White, No. 1 the exquisite modulation of whites and greys is counterpointed to the figure’s auburn hair and pink-white skin. In the production of white as a racialized signifier, as Angela Rosenthal compellingly argued, whiteness is (portrayed as) pink.[24] And more than any other textile, gossamer-fine white muslin acts as a revealing veil for pink skin, as the transparent sleeves of John Singer Sargant’s Lady Agnew of Lochnaw (1892, fig. 11) attest. The white paintings, along with Whistler’s Orientalist melange pictures, in which an Irish model impersonates an Asian woman (fig. 9), actively produce an ideal of whiteness across class, nation, race, and ethnicity.[25] They are central to the cultural work that was involved in making what Jennifer DeVere Brody identifies as “impossible purities.”[26]

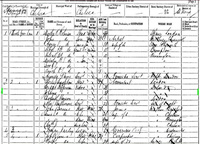

“What do we really know of Joanna Hiffernan?” asks Margaret MacDonald, concluding that “[e]stablishing her identity is no easy matter” (31, 15). In “Joanna Hiffernan and James Whistler: An Artistic Partnership,” the only chapter devoted to Hiffernan, MacDonald sketches Hiffernan’s personality, friendships, and associations from letters and recollections, recounting her travels with Whistler, her circulation in artistic circles, her closeness to her sisters. She builds on de Montfort’s earlier accounts and suggestion of a collaborative partnership between model and artist.[27] MacDonald discloses a transformative discovery: Hiffernan was baptized at St Mary’s Catholic Church in Limerick, Ireland, in 1839. When she met Whistler, Hiffernan was an adult woman aged twenty-one. By 1843 the Hiffernan family had migrated to London and was living in Lambeth, a district south of the Thames where the population had escalated to over 100,000.[28] In 1851 the family was in Marylebone, though Joanna was not listed by the census enumerator.[29] MacDonald points to anti-Irish prejudice, and the “horrifying poverty” that caused the death of Catherine Hiffernan (born 1848) in January 1859 from malnutrition. Yet there is little in her account that textures the specific minority conditions of Irish communities in the largest global city in the world, the metropolitan center of an empire, and home to many ethnically diverse populations. From this chapter’s opening words—“The ambitious young artist James Whistler”—Hiffernan’s story unfolds as she interacts with him. What follows here is a re-telling, drawing on MacDonald and other resources, in an attempt to re-center her.

The Hiffernans were among the thousands who left Ireland in the long nineteenth century, especially in the years of the Great Famine (1845–49). They joined London’s established and fast growing Irish communities, finding lodgings in densely built, overcrowded inner-city areas. Their lives and experiences were often “marked by discrimination, hostility, and poverty; and by a general harshness of existence.”[30] Racism was fuelled by anti-Catholic prejudice and perpetuated by vicious stereoptyping of the Irish as uncivilized and inferior.[31] Epidemic infections, poor sanitation, environmental pollution, food insecurity, and malnutrition contributed to high mortality rates.[32] Diverse and varied in occupation, these resourceful and adaptable workers contributed substantially to British economy, culture, and society. According to his daughter Agnes, John Christopher Hiffernan was a “Schoolmaster” who had passed away by 1886 (fig. 14); this occupation is also given in the 1851 census and on his daughter Ellen’s marriage record in 1866.[33] Joanna Hiffernan’s sense of Irishness and her experience as an Irish woman in the diaspora remain unexplored. Courbet recollected she sang Irish songs.[34] Did she sing traditional songs, in the Irish language, unaccompanied, songs that conjured home away from home?

Hiffernan met Whistler in 1860; she and her family then lived in Marylebone, a district populated with artists, art schools, and artists’s suppliers.[35] The 1861 census lists Whistler as “Artist /Painting,” “Visitor Husb[and]” with “Anna Whistler” “Visitor /Wife,” presumably Joanna Hiffernan, at 4 Lucas Street, Rotherhithe (south of the river and not far from the Surrey docks, shipping, and wharves), in the family home of William Davidson, a corn meter.[36] The couple were in Paris together over the winter of 1861–62 when the first white painting was underway. De Montfort places them at 7a Queen’s Road West in Chelsea by June 1862, moving to “a pretty eighteenth-century house” at 7 Lindsey Row in spring 1863.[37] US diplomat Benjamin Moran recorded an occasion when Hiffernan took him and the artist’s half-brother George on a studio visit:

met James Whistler, a brother of Geo. W., who is an artist of rising reputation in Europe. He was on his way to the continent and his mistress was there to bid him good bye. George and I went home with her to her house in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, where I saw several remarkable pictures by him. . . . we took tea and left at 11[pm]. The mistress is an Irish girl, with the golden tresses of Venus, and deep blue eyes as large as those of Juno.[38]

Moran testifies that in Whistler’s absence Hiffernan showed artworks to visitors, entertained them, and was acquainted with at least one of Whistler’s siblings. She may have made artwork (15) and she is pictured painting in Purple and Rose. Her position altered decisively when, in the midst of the Civil War, Anna McNeill Whistler relocated to London to reside with her son.[39] His mother’s imminent arrival early in 1864 prompted Hiffernan’s expulsion and erasure. Dispatching her to a “buen retiro” Whistler wrote, “I had a week or so to empty my house and purify it from cellar to attic!” He regretted the loss of the “quiet and peaceful work of my studio” facilitated by Hiffernan.[40] Hiffernan continued to model for Whistler and in 1865 travelled with him to Trouville in France where she sat to Courbet. At Lindsey Row, Mrs. Whistler settled into her new life and stayed eleven years. She reported her son was “too closely confined to his Studio. I never am admitted there nor any one else but his models.”[41] Seemingly unaware of his closeness with Hiffernan, the model for Purple and Rose, she wrote: “he is finishing at his Studio (for when he paints from life, his models generally are hired & he has for the last fortnight had a fair damsel sitting as a Japanese study) a very beautiful picture.”[42]

In 1866, Hiffernan was living at 14 Walham Grove, Fulham, a thirty-minute walk, one and a half miles further west; according to MacDonald this was her “buen retiro” from 1864 (27).[43] She moved to lodgings in a new house in a new street. Nothing is yet known about her situation in the house, or those with whom she lived.[44] Built around 1862, the first terrace (1–16) comprised identical pairs of linked semi-detached villas, each with two floors, stepped access to the side, and a semi-basement with separate entrance; the original plan seems to have provided two main rooms on each floor. The houses are set well back and separated from the road by railings.[45] A contemporary map (fig. 12) shows the first terrace of houses with their gardens on the north side, a second block (19–26) further along. Walham Grove is so new it is not yet named. Semi-rural, with market gardens, small farms, allotments, nurseries, breweries, and brickfields, the area was becoming more urban and residential.

MacDonald describes Hiffernan: “A red-haired woman of rare beauty, with a joyous and passionate temperament, she was a capable manager, patient model, and faithful friend to Whistler” who “necessarily helped to organize Whistler’s studio and finances and is said to have sold works both with and without his approval” (31, 18). During Whistler’s absence in Chile in 1866, she agreed to weighty responsibilities, codified in a legal document that granted “Joanna Hiffernan of 7 Lindsey Row” power of attorney to manage his affairs, and to sell his artworks “for the best prices she can obtain”; “the rent taxes servants and all expences [sic] of clothing and living of the said Joanna Hiffernan” were to be provided.[46] These legal provisions were unravelled by the financial crisis of May–June 1866. Whistler’s bank was acquired and liquidated, and Hiffernan, like so many, encountered serious financial difficulties. She asked James Anderson Rose, lawyer to Whistler and D. G. Rossetti, for a loan of ten pounds, explaining that “none of Mr Whistler’s pictures have yet been Sold,” and offering as security “any one of Mr Whistler’s Seaviews that are now at Mr Rossettis.”[47]

Little is known about Hiffernan in the 1870s and 1880s. In the 1881 census (fig. 13) she, her sister Bridget Agnes, and Charles Hanson are listed as “Visitors” at 2 Thistle Grove Lane, Chelsea, the home of Charles James Singleton, an accountant and friend of Whistler (fig. 12).[48] Assembling fleeting references, MacDonald concludes that she kept in touch with Whistler, stayed frequently at Thistle Grove Lane (where was she otherwise?), and with Agnes cared for Charles Hanson (b. 1870), the artist’s son with Louise F. Hanson. Hanson’s touching recollection of being gathered up by the sisters gives a magical sense of their physical presence: “Two women, Joanna and Mrs S. come on the scene and they lift me up and caress me. . . . I leave the abode of my foster mother. I am taken on a long journey and eventually reach my future home” (29–30). De Montfort drew attention to the recollection of Walter Dowdeswell (Whistler’s dealer in the 1880s) that Hiffernan visited him “with bundles of prints or drawings she would sell for anything she could get.”[49] Was she still acting as an art market intermediary, or did she sell artworks to support herself and/or Charles Hanson?

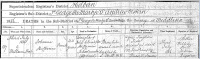

Joanna Hiffernan died of bronchitis on July 3, 1886, at 2 Millman Street, Bloomsbury, near the Foundling Hospital (fig. 14). Her sister Agnes registered her death, giving Joanna’s age as 44.[50] In Whistler’s drypoint of 1875–78, Agnes Hiffernan is stylishly dressed in the new slimmer silhouette, with possibly a looped overskirt, her hair neat with a fashionable high chignon and short fringe.[51] In 1886 she resided at 152 Southampton Row, Russell Square, a short walk from Millman Street. In the 1891 census she is registered at 9 Baker Street in Clerkenwell as Agnes Singleton, “living on her own means,” born in Limerick in 1842, together with Charles J. W. Hanson “commercial traveller tobacco” aged 20 and Theresa Fisher, a domestic servant.[52] She styled herself “Agnes Singleton” in the 1880s and 1890s, although she did not marry Singleton until 1901.

Nothing belonging to Joanna Hiffernan seems to have been preserved; little by her has survived. Much about her, as MacDonald admits, remains elusive. Her hair was often remarked on, but the timbre of her voice is long forgotten. If Whistler kept any papers by or to her, they have not surfaced: MacDonald indicates that “many of his more personal letters” were destroyed (31). The histories of women are often precarious and fugitive; historical records can be sparse, unreliable, and partial. Counter-strategies—unpicking narratives, re-reading documents, examining absences, challenging prevailing interpretations, searching beyond the Whistler archive—and the resistant work of “brushing history against the grain,”[53] will assist in reassembling Hiffernan’s life in diaspora.

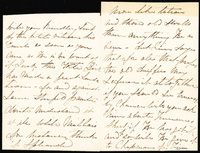

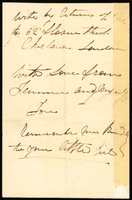

The only surviving document that speaks in Joanna Hiffernan’s voice, and one of the very few that captures her handwriting, is a single letter to US art agent and collector George A. Lucas retained in his archive (figs. 15, 16, and 17).[54] Hiffernan writes on folded note-paper with a black border, still mourning her mother’s death in March; the top of the first page has been torn off.

London April 9th 1862

My dear Lucas

did you get the Lath and Easeal all right that we sent you by the Concierge the morning we left Paris; Jim is so very much occupied just now that he [h]as no time to write himself therefore He desires me to write for him to you –

Will you kindly send by the petite vitesse his Easeal as soon as you can as He is in want of it Just [now], - The W[h]ite Girl has made a great sensation - for and against[.] Some stupid painters dont understand it at all while Millais for instance thinks it spleandid more like [T]itian and those old swells than anything He [h]as seen - but Jim says that for all that - p[e]r[h]aps the old duffers may refuse it altogether - if you should see Ernest by chance will you ask him about Jimmie’s shirt if He has got it, and if so will He give it to Chapman for Jim[.]

Write by return of post to 62 Sloane Street

Chelsea London.

With love from

Jimmie and myself

Joe

Remember me kindly to your little girl.[55]

This singular document is revelatory in so many respects. Hiffernan’s letter is the first to give Symphony In White, No. 1 its first title of “The White Girl”; to characterize its first exhibition as “a great sensation—for and against”; to rightly predict the picture’s rejection by the Royal Academy; to acknowledge that the picture will not be understood (it is still puzzling viewers and scholars); and to testify to its admiration by John Everett Millais. The letter is shot through with Hiffernan’s thoughtful, intelligent understanding of the contemporary art world. Whistler relied on Lucas to carry out practical tasks: he is asked to dispatch the easel consigned to him when the couple hurriedly left Paris on the news of the death of her mother, and to retrieve Whistler’s shirt. Though she is, she admits, writing at Whistler’s behest, and even if she is ventriloquising, Hiffernan writes in a warm manner and a colloquial style: “duffers” and “swells” connote her disapproval and esteem. Friendship is evident in her post-script greeting to Octavie Josephine Macedo-Carvalho, Lucas’s companion.[56] Variant (mis-)spellings indicate a patchy education.

Hiffernan makes reference to Titian, an artist admired by Whistler. Titian’s portraits of the 1560s such as Lady in White (ca. 1561, fig. 18) feature narrowish sleeves with a puff or roll at the armscye, comparable to the shoulder details in Symphony in White, No. 1. The sheer partlet covering the shoulders above the low neckline is not dissimilar to the fine layering of the upper bodice in the second and third white paintings. If actual dresses existed and if they were created by Hiffernan, she was an accomplished needlewoman and costume designer who blended artistic style with touches of contemporary fashion and historical detailing. In 2003 De Montfort located a surviving white linen daydress, comparing it persuasively to the attire in Symphony in White, No. 2.[57] De Montfort considers Hiffernan may well have sewn the dresses. Jottings in Whistler’s notebook from ca. 1862–64 describing enough fabric for a wide-skirted, full-sleeved dress may have been written entirely or in part by Hiffernan: “14. Yards – dress -/ 8 widths - in skirts -/ Bonnet -/ Lawn 11.y[ards]. 3/4./ 5 widths - 6 if possible / Sle[e]ves to be made the wi[d]th of the Muslin.”[58]

The shape and style of the ensemble in Symphony in White, No. 1 emphasizes the figure’s statuesque poise. Fabrics are varied in weight, color, pattern, and stitching. The exaggerated shoulder puffs counter the streamlined bodice and sleeves; the snug fit of the stitched-down pleats contrasts to the capacious skirt released from folds at the waist. The pronounced angles of the hem suggest that the skirt fabric, like the cuffs, may have been stiffened. In The Open Book Hiffernan wears a dress more in line with contemporary fashion, with a voluminous skirt, full sleeves tapering below the elbow, and a button-through high-necked bodice in a softly rounded shape created by upward darts (1861, fig. 19). She wears a similarly wide-skirted, wide-sleeved dress in Weary (1863, fig. 20) and in two drawings, The Sleeper (1863) and Sleeping Woman (1863, fig. 21). George Du Maurier’s sardonic 1862 comment, “Joe came with him . . . got up like a duchess, without crinoline—the mere making up of her bonnet by Madame somebody or other in Paris cost 50fr,” indicates her preference for the ease and grace of skirts supported by petticoats rather than a crinoline.[59]

Hiffernan’s hair is usually conspicuous. Unrestrained, her hair wriggles free, cascading down her shoulders and back (figs. 1, 2, 3), billowing around her face (figs. 20, 21). That Whistler, introducing her to Courbet, “let down her hair and ‘drew it over her shoulders,’”[60] suggests that she would tie it back. Her stylish bonnet would have required a tidy arrangement. In The Open Book her hair is loosely coiled at the back of her neck (fig. 19). Adult women’s hair was generally highly controlled outside intimate or domestic situations. Hiffernan’s informal hair styling contrasted to contemporary fashion for a smoothed, glossy head offset with an ornate chignon or curls.

Hiffernan was a versatile model. A timeline of her biography and modelling (absent in The Woman in White) would demonstrate how hard she worked over a few years. Whistler was renowned for his long sittings. She posed for finished paintings, studies, prints, illustrations in periodicals, and in varied guises including as a model in an artist’s studio, again attired in white (fig. 22). She is forever young, a woman in her early twenties. In the license of an intimate relationship, Hiffernan is portrayed sleeping, dozing, sitting reflectively, caught unawares, unknowingly perhaps, as well as alert and aware she is being regarded. In Weary (fig. 20) she reclines in an enveloping chair, her hair loose, her lips open, her eyes averted, her body still; she is simultaneously elsewhere, withdrawn, absorbed in thought, declining to entertain the gaze fixed on her. In Sleeping Woman (fig. 21), is her breast revealed by the open bodice or short jacket? Interpretation is divided, de Montfort viewing these images as “moments of quiet domesticity,” others judging Whistler to be taking advantage.[61] Both perspectives are delicately captured in Cherry Smyth’s 2013 novel Hold Still:

Jim has lit the fire and she sits beside it, her hair fanned out along the back of the chair to help it dry. They do not speak. She falls asleep, watching the flames unfurl and flicker. . . . When she opens her eyes, Jim is sketching her on a copperplate resting on a drawing board balanced on the arms of the chair.

“You could ask.”

“Don’t be unreasonable. You were asleep.”

“I have reason to be unreasonable.”

She gets up and stretches and tilts her head from side to side. He reaches for her hand but misses as she moves past him.

“Oh Jo, wait, you looked so beautiful in the firelight –”

“Ah give over Jim, I’m weary . . . ”[62]

Hold Still gives a vivid account of Hiffernan’s life in London and France in the 1860s charged by world events and by the intensity of her relationships. For this Irish-born writer, Ireland becomes a place in living memory; Hiffernan is likened by her father to a small, hardy plant that grows in the vast rocks of County Clare (143). Smyth rescues John Christopher Hiffernan from the Irish stereotyping that has infected Whistler literature since Elizabeth Robins Pennell and Joseph Pennell remarked that he was “described to us as a sort of Captain Costigan,” Thackeray’s fictional character of a drunken Irishman.[63] Reading between the lines, catching at traces and absences, Smyth tells the story of a courageous, generous, supportive, independent woman, buffeted at times by the needs of others, who makes a fictional journey from model to successful artist.

Though artists’s models have long featured in fiction, most famously in Du Maurier’s Trilby (1894), they have been little regarded in academic scholarship until recently. Denise Murrell’s pathbreaking research on the presence, agency, and active participation of Black women models in French art transforms and re-writes accounts of modern art, modernity, and modern urban culture.[64] Murrell draws attention to the many women of color in artistic circles in the French capital; modelling populations in London and Paris were culturally and ethnically diverse.[65] Irish and Italian models found employment in London (fig. 23) as did women of color like Fanny Eaton.[66] Labor studies differentiate between professionals and members of the artist’s social and familial circles. Either way, modelling was tiring, tedious, demanding, and exacting. Professionals undertook sittings at life classes, art schools, and artists’ studios; their work was badly paid and low status.[67] Susan Waller proposes “the artist/model transaction” to highlight the recriprocity of the encounter within social formations and power relations of gender, class, race, and ethnicity.[68]

The relatives, associates, wives, and companions of artists often sat as their models, formally and informally. In addition, family members and partners would make costumes, carry out research, seek out accessories, entertain, cultivate clients, and undertake household and business management. Reviewing this wide range of potential activities, Jan Marsh defines Pre-Raphaelite women models as “artistic collaborators,” making an “active participation in the picture-making process.”[69] Though she may have started out as a professional (15), Hiffernan soon become a partner model: she carried out many of these tasks for Whistler and sat (almost) exclusively to him. Whistler was possessive and controlling, informing the artist Frederick Sandys, “Jo says many things aimables—and if ever I lent her to anyone to paint, it should certainly be to you mon ami.”[70]

Across the catalogue, Hiffernan comes into focus only to disappear like a ghost into the suffocating crowds of women in white. She is as visible and as excised as the scratching out of her head and face in Whistler’s cancelled print, The Open Book (see fig. 19). If Joanna Hiffernan, the woman who looks so directly out in Jo (1861, fig. 24), is to become the primary subject of enquiry, then she needs to be placed center stage, with Whistler a signficant other in her story, not its propellant. For now, to reprise the Guerrilla Girls, she has the advantage of “[b]eing included in revised versions of art history.” Considering Whistler’s “white years”[71] within the numerous images and texts that sustained white supremacy by producing white as the privileged racialized category, and reassembling the life of Joanna Hiffernan, an Irish woman in diaspora, will assist a fuller understanding of the contested terrains of modernity and modern art and the writing of their histories.

Acknowledgements

Warmest thanks to Jane Beckett, Jennifer DeVere Brody, and Meaghan Clarke for their wise comments and generous advice, to Vicky Holmes and the Women’s History Network for their support, and to Sarah Dansberger and Colleen Hollister of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Notes

[1] Guerrilla Girls, The Advantages of Being A Woman Artist, 1988, https://www.guerrillagirls.com/projects.

[2] MacDonald wisely dissociates Hiffernan from Le Sommeil (1866) and L’Origine du Monde (1866) (26).

[3] I refer to these works with a short-form title throughout. For the exhibition see Thomas Hughes, “Review of Whistler’s Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan at the Royal Academy,” 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century 19 Live (2022): 2–9, https://doi.org/10.16995/ntn.8934.

[4] Alice Mackrell, review of The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler, Costume 56, no. 2 (2022): 268–70, https://doi.org/10.3366/cost.2022.0235 [login required].

[5] In summer 1859 Whistler invited Henri Fantin-Latour to London to see “les Gainsborough et nos anciens amours.” The British Exhibition of Old Masters included forty-two portraits and landscapes by this artist. [June 29, 1859], in Margaret MacDonald, Patricia de Montfort, and Nigel Thorp, eds., The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler, 1855–1903. Online edition. http://www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk/, henceforth GUW, GUW 08050. Deborah Cherry and Jennifer Harris, “Eighteenth-Century Portraiture and the Seventeenth-Century Past: Gainsborough and van Dyck,” Art History 5, no. 3 (1982): 287–309, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.1982.tb00769.x.

[6] Color polaroid print, 2002, National Portrait Gallery, London, P965, https://www.npg.org.uk/, channels Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Portrait of Madeleine (1800), https://collections.louvre.fr/.

[7] Sarah Herring and Emma Capron, Discover Manet & Eva Gonzalès (London and New Haven: Yale University Press; London: National Gallery, 2022). In the early twentieth century the portrait was acquired by Hugh Lane and is now in the Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin. Illuminating chapters explore the relationship of the two artists, Manet’s working processes, and the painting’s afterlives.

[8] Robin Spencer, “Whistler’s ‘The White Girl’: Painting, Poetry and Meaning,” Burlington Magazine 140, no. 1142 (May 1998): 308, https://www.jstor.org/stable/887886.

[9] “le piano - La Fille blanche - Les Tamises - les vues de mer . . . . des toiles enfin produit par un polisson qui se gonflait de vanité de pouvoir montrer aux peintres des dons splendides” [September 1867?], Whistler to Henri Fantin-Latour, GUW 08045.

[10] Spencer, “Whistler’s ‘The White Girl’,” 309.

[11] John Gage’s major publications on color and color theory are not listed in the Selected Bibliography.

[12] Whistler to William Hepworth Dixon, July 1, 1862, GUW 13149.

[13] Spencer, “Whistler’s ‘The White Girl’,” 300n5, quotes William Campbell’s observation based on x-radiographs taken in 1976: “the bottom of the window is indicated by the horizontal line just below Jo’s finger tips; the left side runs about six inches from the left edge of the picture; the right edge is uncertainly placed. The window area is indicated by the lighter, warmer and somewhat more yellow area of the drapery, which has a sort of luminous glow.”

[14] “Jo en robe de toile très blanc, la même robe que la fille blanche d’autrefois - cette figure est tout ce que j’ai fait de plus pur - tête charmante. Le corps, les jambes, etc., se voient parfaitement à travers la robe,” Whistler to Alphonse Legros, August 16, [1865], GUW 11477.

[15] British textile manufacture relied on raw cotton grown on the slave plantations of the United States south. The Northern blockade of southern ports during the Civil War halted the export of raw cotton, provoking economic crisis, mill closures, unemployment, and poverty. Whistler contributed “The Relief Fund in Lancashire” to Once a Week, July 26, 1862, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 22.112.2 (plate 14). On muslin see Sonia Ashmore, Muslin (London: V&A Publishing, 2012); on cotton see Sofi Thanhauser, Worn: A People’s History of Clothing (New York: Pantheon, 2022), and Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A New History of Global Capitalism (London: Penguin, 2015).

[16] Alieen Tsui, “The Phantasm of Aesthetic Autonomy in Whistler’s Work: Titling The White Girl,” Art History 29, no. 3 (June 2006): 444, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.2006.00509.x. See also Robin Spencer, “Whistler’s ‘The White Girl’;” Caroline Arscott, “Whistler and Whiteness” in The Colours of the Past in Victorian England, ed. Charlotte Ribeyrol, Cultural Interactions: Studies in the Relationship between the Arts, 38 (Oxford: Lang, 2016): 47–70. Symphony in White: No 3 is the first stand-alone title, inscribed on its canvas.

[17] Jacques Derrida, “Living On,” trans. James Hulbert, in Jacques Derrida, Parages, ed. John P. Leavey (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010), 103–191.

[18] Judith Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). Laura Lammasniemi, “‘Precocious Girls’: Age of Consent, Class and Family in Late Nineteenth-Century England,” Law and History Review 38, no. 1 (February 2020): 241–66, https://doi.org/10.1017/S073824802000005X. In late nineteenth-century discourses on “white slavery” white was a racialized differential. Rachael Claire Attwood, “Vice Beyond the Pale: Representing ‘White Slavery’ in Britain c. 1880–1912” (PhD diss., University College London, 2013). The UK age of consent was raised to 13 in 1875, 16 in 1885.

[19] Joanna Hiffernan to George Aloysius Lucas, April 9, 1862, GUW 09186. For Macedo-Carvalho, see GUW.

[20] This insight comes from Martha Stoddard Holmes, “Intellectual Disability,” Victorian Review 40, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 9, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24497027.

[21] Daniel E. Sutherland, “James McNeill Whistler in Chile: Portrait of the Artist as Arms Dealer,” American Nineteenth Century History 9, no. 1 (March 2008): 62, https://doi.org/10.1080/14664650701800575. See also n. 39.

[22] The so-called “Governor Eyre controversy” pitched factions headed by Thomas Carlyle and John Stuart Mill in support of and against Eyre’s violent suppression. On Whistler’s portrait of Carlyle, see Joanna Meacock, “Arrangement in Racism and Black Injustice: Whistler’s Colour Theory,” https://glasgowmuseumsslavery.co.uk/.

[23] Alexis Clark, “Impressionism as Erasure: Whistler and the Chincha Islands War,” in Mapping Impressionist Painting in Transnational Contexts, eds. Emily C. Burns and Alice M. Rudy Price (New York and London: Routledge, 2021), 35.

[24] Angela Rosenthal, “Visceral Culture: Blushing and the Legibility of Whiteness in Eighteenth-Century British portraiture,” Art History 27, no. 4 (September 2004): 563–92, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0141-6790.2004.444_5_5.x. Ribeiro acknowledges “a white complexion for women was considered the ideal,” 157.

[25] On these works, see Ayako Ono, Japonisme in Britain (New York: Routledge Curzon, 2003). Whistler wrote of Purple and Rose: “C’est rempli de superbes porcelaines tirés de ma collection, et comme arrangement et couleur est bien - Cela represente une marchande de porcelain, une Chinoise en train de peindre un pot -” (It is filled with superb porcelain from my collection, and is good in arrangement and color - It shows a porcelain dealer, a Chinese woman painting a pot). Whistler to Fantin-Latour, January 4–February 3, 1864, GUW 08036.

[26] Jennifer DeVere Brody, Impossible Purities: Blackness, Femininity, and Victorian Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998), seeks to “unmask the performative nature of whiteness that too often has been ‘seen’ as the unmarked, unchallenged normative site of power” and to expose the construction and historical specificities of white (8–9). I am deeply indebted to Jennifer DeVere Brody for her constructive input: “the modern construction of whiteness as an ideal being formed through white supremacy exactly at the moment of the Civil War where Whistler openly stated his sympathy for the South.” Email to the author, October 23, 2022.

[27] Patricia de Montfort, “White Muslin, Joanna Hiffernan and the 1860s,” in Margaret MacDonald, Susan Grace Gallassi, and Aileen Ribeiro, with Patricia de Montfort, Whistler, Women, and Fashion, exh.cat. (New York: Frick Collection with Yale University Press, 2003), 76–91. Patricia de Montfort, “Joanna Hiffernan,” in Dictionary of Artists’s Models, ed. Jill Berk Jiminez (London: Taylor and Francis, 2013), 296–98.

[28] https://www.british-history.ac.uk/.

[29] Public records accessed through www.ancestry.co.uk and www.findmypast.co.uk. At 10 Little Marylebone Street are five households with eleven adults and ten children.

[30] Tom Herron, Irish Writing London, 1:1, quoted in Richard Kirkland, Irish London: A Cultural History 1850–1916 (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2021), 12.

[31] Fintan Cullen, Visual Politics: The Representation of Ireland, 1750–1930 (Cork: Cork University Press, 1997).

[32] Donald MacRaild, The Irish Diaspora in Britain, 1750–1939 (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2010); Richard Kirkland, Irish London. On Irish artists and writers see Fintan Cullen and Roy Foster, Conquering England: Ireland in Victorian London, exh. cat. (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2005). On the Irish in the US, see Noel Ignatiev, How the Irish Became White (London and New York: Routledge Classics, 2008).

[33] According to MacDonald, Hiffernan worked in construction in hard times (15); if so he was, like many, subject to migrant deskilling. Ellen Hiffernan married Frederick Walter Stokes, a London wine merchant, in May 1866 at St. Luke’s Church, Chelsea.

[34] “rappelez-vous Trouville et Jo qui faisait le clown pour nous egayer. le soir elle chantait si bien les chants Irlandais car elle avait elle avait l’esprit et la distinction de l’art.” (do you remember Trouville and Jo who played the clown to amuse us. the evening she sang Irish songs so well [,] she had the spirit and the distinction of art). Gustave Courbet to Whistler, [February 14, 1877], GUW 00695.

[35] According to GUW, her family lived at 69 Newman Street; Whistler was next-door, sharing a studio with George du Maurier. https://www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk/. See also Kitt Wedd with Lucy Peltz and Cathy Ross, “‘Artists’ Street’ in Marylebone,” Creative Quarters: The Art World in London, 1700–2000 (London: Museum of London, 2001), 68–81.

[36] Whistler is also listed as “Artist” with his mother, at 15 Hemus Terrace, Chelsea. Also at no. 4 Lucas Street were Philip Wright, laborer, his wife Ellen, and their son.

[37] Whistler lived at 7 Lindsey Row, Chelsea, March 1863 to ca. January 1867.

[38] The Journals of Benjamin Moran 1857–1865, eds. Sarah Agnes Wallace and Frances Elma Gillespie (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1949), vol. 2, 1149, italics original. Moran (1820–86) worked at the United States Legation in London. Quoted in part in de Montfort, “White Muslin,” 84. George William Whistler (1822–69), was the artist’s half-brother.

[39] The editors of GUW refute the impact of current events, writing: “When Anna left her native land for London in 1864, it would be a mistake to think that this was to escape the ravages of the civil war. . . . Naturally the mother wanted to be where her children were.” Biography of Anna McNeill Whistler, GUW, https://www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk/. Deborah Delano Haden (1825–1908) (her step-daughter) lived with her husband Frances Seymour Haden in comfortable prosperity at 62 Sloane Street; her son William McNeill Whistler (1836–1900), an assistant surgeon in the Confederate army, arrived at the end of the war on a four-month furlough; according to Sutherland he was apparently carrying “secret dispatches to Confederate agents at Liverpool” and planned to travel with his brother to Chile. Sutherland, “James McNeill Whistler in Chile,” 62–3.

[40] “J’ai eu une semaine à peu pres pour vider ma maison et la purifier depuis la cave jusqu’au grenier! - Chercher un ‘buen retiro’ pour Jo.” “Tout ça a beaucoup dérangé la vie tranquile et paisible de notre atelier.” He continued, “le serieux était la peine que cela causait à ma soeur - Nous ne pouvions plus nous voir que rarement chez des amis mutuels. et tu sais que nous sommes tres dévoués l’un à l’autre” (the bad thing about it was the grief it caused my sister! We could see each other only rarely at the houses of mutual friends, and you know that we are very devoted to each other). Whistler to Fantin-Latour, January 4–February 3, 1864, GUW 08036.

[41] Anna Whistler to James H. Gamble, June 7, 1864, GUW 06524.

[42] Anna Whistler to Gamble, February 10, 1864, GUW 06522.

[43] This address is given on Hiffernan’s letters to James Anderson Rose, March 20, 1866, GUW 11844 and March 22, 1866, GUW 10731.

[44] Du Maurier reported “Joe is turned into lodgings,” quoted in de Montfort, “White Muslin,” 85. On privacy and personal security in lodgings see Vicky Holmes, “The Lodger’s Threshold,” https://drvickyholmes.com/. In “Accommodating the Lodger: The Domestic Arrangements of Lodgers in Working-Class Dwellings in a Victorian Provincial Town,” Journal of Victorian Culture 19, no. 3 (January 2005): 314–31, https://doi.org/10.1080/13555502.2014.947181, Vicky Holmes explains that “the majority of lodgers in Victorian England’s towns and cities resided in private working-class dwellings” and that the “domestic arrangements of lodgers, including where they slept, varied widely.”

[45] This history and description come from Conservation Area Character Profile, Walham Grove, London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, 2000, 3–6. The street was developed by the landowners, the Harwood family. Residential housing flanked both sides of the street by the 1890s. In the 1871 census occupations were master tailor, sanitary inspector, assistant chaplain, clerks, agents, army captain, annuitants, and property holders; at no. 14 were Samuel Millard, a coppersmith, Mary, and their two teenage children. Most were single households, several with one servant. Irish agricultural laborers lived in the locality. Artists, related trades, and cultural workers also lived in Fulham.

[46] Rose to Hiffernan, January 31, 1866, GUW 11480. Hiffernan was named the main beneficiary of Whistler’s 1866 will (27, 199). She also negotiated repairs at Lindsey Row with the landlord and Rose.

[47] Hiffernan to Rose, May 14, 1866, GUW 11484. Whistler banked with Bank of London, writing to authorize Hiffernan, Whistler to Rose, January 31, 1866, GUW 12125. When Bank of London encountered financial problems, it was acquired by Consolidated Bank, who stopped payments for six weeks. https://www.natwestgroup.com/. Papers preserved by Rose, GUW 13752, 13753, 13754, 13755, and 13753, June 22, 1866, stake a claim as a creditor in Bank of London’s liquidation: “For J. A. M. Whistler per Joanna Hiffernan.”

[48] Charles James Singleton (1841–1918) was an accountant with expertise in bankruptcy and liquidation (listings in London Gazette); Whistler hoped he would act for him in his bankruptcy, January 29, 1879, GUW 08760.

[49] Quoted in de Montfort, “White Muslin,” 80.

[50] If Hiffernan was born in 1839 she died aged 50/51. The 1881 census gives her age as 38, dating her birth to 1843. In the 1891 census 2 Millman Street accommodated twenty-three people in several households; Hiffernan probably rented a single room.

[51] James McNeill Whistler: The Etchings, eds. Margaret F. MacDonald, Grischka Petri, Meg Hausberg and Joanna Meacock, 2012, no. 146, https://etchings.arts.gla.ac.uk.

[52] Agnes registered as a voter in the 1919 Electoral Register, the first open to women in the UK; she was then resident at Montagu Mansions, Marylebone, where she had lived with her husband Charles Singleton.

[53] This phrase by Walter Benjamin has inspired historical interpretation that runs counter to that produced by the historical “victors.” “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” (1940) in Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zorn (London: Fontana/Collins, 1973), 258–59.

[54] On Lucas see Stanley Mazaroff, A Paris Life, A Baltimore Treasure: The Remarkable Lives of George A. Lucas and His Art Collection (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018), 102. John A. Mahey, “The Letters of James McNeill Whistler to George A. Lucas,” The Art Bulletin 49, no. 3 (September 1967): 247–57, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3048475. GUW notes Lucas’s diary for April 10, 1862, “10. Thursday. Rec’d letter from Whistler.” The Diary of George A. Lucas: An American Art Agent in Paris, 1857–1909, ed. Lillian Randall (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979), 133.

[55] Joanna Hiffernan to George Aloysius Lucas, [April 9, 1862], GUW 09186. My transcription. “Duffer,” OED 1842: colloq. “A person without practical ability or capacity. Also, generally, a stupid or foolish person.”

[56] “Jo tells me to send her kindest regards to yourself and Madame.” Whistler to Lucas, [May 3, 1869], GUW 9190.

[57] Dress ca.1864, United States, bleached linen tarlatan with matching sash, The Museum of the City of New York, Gift of the Misses Braman, 47.83.1A-B, 89. Reproduced Ribeiro, 161.

[58] De Montfort, “White Muslin,” 89; GUW 12745.

[59] Daphne Du Maurier, ed., The Young George du Maurier: A Selection of His Letters, 1860–67 (London: Peter Davies, 1951), 105. If Hiffernan wears a crinoline in The Open Book, this may explain Du Maurier’s astonishment in seeing her without one.

[60] De Montfort, “White Muslin,” 80.

[61] De Montfort, “White Muslin,” 80; Margaret F. MacDonald, James McNeill Whistler: Drawings, Pastels and Watercolors, A Catalogue Raisonné (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995), cat. no. 309.

[62] Cherry Smyth, Hold Still (London: Holland Park Press, 2013), 131–32.

[63] Elizabeth Robins Pennell and Joseph Pennell, The Life of James McNeill Whistler (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1908), 94. They also stated that he was a teacher of “polite chirography (handwriting),” The Whistler Journal (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1921), 161. Captain Costigan appears in William Thackeray, The History of Pendennis: His Fortunes and Misfortunes, His Friends and His Greatest Enemy (London, 1848–50).

[64] Denise Murrell, Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018); exhibition Le Modèle noir de Gericault à Matisse was reviewed by Adrienne L. Childs in NCAW 18, no. 2 (Autumn 2019), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2019.18.2.18.

[65] Jennifer DeVere Brody kindly drew my attention to Whistler’s drypoint of the celebrity entertainer Josephine Durwand, known as Finette (1859), https://etchings.arts.gla.ac.uk, no. 61. See also Jan Marsh, Black Victorians: Black People in British Art, 1800-1900 (London: Lund Humphries, 2005), no. 100.

[66] On Fanny Eaton see Jan Marsh, Pre-Raphaelite Sisters, exh.cat. (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2019) who acknowledges the endeavors of Brian Eaton.

[67] Martin Postle, “Naked Civil Servants: The Professional Life Model in British Art and Society,” 9–25, in Model and Super-Model: The Artist’s Model in British Art and Culture, ed. Jane Desmarais, Martin Postle and Martin Vaughan (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006). Reviewed by Susan Waller in NCAW 7, no. 1 (Spring 2008), https://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/.

[68] Susan Waller, The Invention of the Model: Artists and Models in Paris, 1830–1870 (New York: Routledge, 2016).

[69] Marsh, Pre-Raphaelite Sisters, 16, 18.

[70] Whistler to Anthony Frederick Augustus Sandys, [May 31/June 1863], GUW 09455.

[71] Nicholas Daly, “The Woman in White: Whistler, Hiffernan, Courbet, Du Maurier,” Modernism/Modernity 12, no. 1 (January 2005): 2, https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2005.0039.