Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899)

Reviewed by Verónica Uribe HanaberghVerónica Uribe Hanabergh

Associate Professor, Art History Department

Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia

Email the author: v.uribe20[at]uniandes.edu.co

Citation: Verónica Uribe Hanabergh, exhibition review of Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899), Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.1.20.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899)

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux

May 18–September 18, 2022

Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899)

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

October 18, 2022–January 15, 2023

Catalogue:

Sandra Buratti-Hasan and Leïla Jarbouai,

Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899).

Paris: Flammarion, 2022.

288 pp.; 239 color and b&w illus.; timeline; list of artworks exhibited; select bibliography; index; photographic credits.

€45 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978–2–08028–096–1

To celebrate the 200th anniversary of Rosa Bonheur’s birth, the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux (the artist’s birthplace) and the Musée d’Orsay in Paris (the city where Bonheur lived for most of her life) recently organized this retrospective exhibition. The curators—Sophie Barthélémy, Sandra Buratti-Hasan, Leïla Jarbouai, and Katherine Brault—assembled an unforgettable exhibition of the well-known animal painter. The show was comprised of more than two hundred works of art, including paintings, prints, sculptures, and photographs, mostly made by Rosa Bonheur but also by her father, friends, and lifelong companions.

The exhibition in Paris began before actually entering its galleries, on a long wall painted in a deep violet hue and bearing a timeline of the artist’s life and several black and white prints and photographs introducing Bonheur to visitors (figs. 1 and 2). These included a photograph of Rosa Bonheur and William F. Cody surrounded by a group of actors at the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show in Paris in 1889 and a print of Rosa Bonheur’s atelier on Rue de l’Ouest that appeared in L’Illustration on May 1, 1852. The same purple color was used in several rooms of the exhibition, with others painted in mauve, gray-green, and beige tones.

Upon entering the show, viewers were greeted by an intimate space that presents Rosa Bonheur, the girl, the daughter, the artist, and the persona through three oil portraits by Raimond Bonheur (1826), Édouard Dubufe (1857), and Consuelo Fould (1893). The first large room (fig. 3) displayed, in no subtle way, Bonheur’s well-known masterpiece of 1849, Ploughing in the Nivernais. The curators chose to immediately and unapologetically suggest the artist’s greatness through one of her largest and most accomplished works instead of slowly or timidly narrating her career. At twenty-seven, Bonheur was capable of suggesting her spiritual affinity with different animals—in this case, domesticated cattle. Other smaller paintings and sculptures in the room testify to the productivity that defined Bonheur, but Ploughing in the Nivernais, because of its size, appears as a breakthrough. It testifies that Bonheur strode into the world of animal painting, a genre traditionally reserved for male artists, with fierceness, humanity, and a unique understanding of the subject before her.

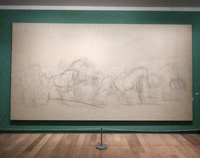

As if this grand introduction were not enough, the second room featured two horizontal works, an enormous oil painting and its equally large pencil sketch, which the space is just large enough to accommodate. Painted when she was between thirty and thirty-three years old, The Horse Fair (1852–55) again demonstrates Bonheur’s audacity, energy, and capacity to enter the male sphere of energetic animal paintings. A genre scene painted on a 244.5 x 506.7 cm canvas, the painting dominates the room with its massive, muscular, and ill-behaved horses. On the wall next to it hung one of the many sketches made by Bonheur during the process of painting her masterpiece (fig. 4).

What followed was a series of connecting rooms on specific themes and topics that made plain Bonheur’s genius for intimacy, observation, and empathetic connection with animals. Several rooms refer to her travels to places such as the Pyrenees, Scotland, and the Auvergne, where landscape played a key role in her understanding of animal life. Modestly scaled paintings of mules, sheep, and Shetland ponies convey a sense of exploration in various locales. A narrow hallway allows the visitor to slowly and intimately view smaller paintings that suggest Bonheur’s close connection to certain animals. For example, in the animal portrait Toutou, the Beloved (1885, fig. 5), of a small terrier owned by Bonheur sitting on an emerald green cushion, the dog’s gaze engages the viewer with an intensity that only Bonheur could produce. Myriad animal studies—of dogs, cats, foxes, lions, goats, rabbits, eagles, deer, wild pigs, cows, and horses—lined the walls of the exhibition and record Bonheur’s conversations with nature, her surroundings, and her personal menagerie. In some cases, she portrays animals that are hurt, troubled, or tired, like the eye-catching Barbaro, after the Hunt from circa 1858 (fig. 6). This beautifully expressive portrait of a hunched and tired hunting dog introduces Bonheur’s incursion into the masculine genre of hunt painting and testifies to the painter’s relationship to her animal companions.

A central gallery in the exhibition was painted beige and divided into two sections, one entitled “The Animal Studio” and the other “Placing Studies at the Heart of Creation.” It contained drawings, sketches, crayon drawings on cyanotypes, and smaller oil studies, some in display cases (fig. 7). This room presented different ways in which Bonheur apprehended her relationship to the animal world, from pages filled with the different gestures of a fox drawn in pencil, to the undated oil on paper entitled The Wounded Deer, to simple watercolor studies of autumnal forest landscapes, finished horse paintings, and unfinished studies of animal heads. Key for comprehending Bonheur’s work at the mid-point in her career, the room had the feeling of a laboratory for experimental observation and practice. At almost any point of the exhibition, the visitor can return to this room and reconnect with its suggestion of Bonheur’s praxis. In fact, this space has two entrances/exits, one towards the beginning of the exhibition, coming from the two initial rooms, and the other moving forward through the retrospective.

One of the most spectacular moments of the exhibition occurred when one continued on through the exhibition, leaving this large room, with its sketches and drawings on beige walls, and walking directly into a far more intimate, deep purple space (fig. 8). Upon entering this dark gallery, viewers were confronted with the dramatically illuminated, fantastic King of the Forest (1878, fig. 9). The presentation of this painting created the impression of walking through a deep, silent forest and stumbling upon this great, elegant beast. The painting sets itself apart with its solemnity, and through the way in which the stag gazes at the viewer as if he has just been encountered in the middle of nature. Bonheur’s deep rapport with the forest, a place she knew well through walks and excursions near her estate, is captured in this large artwork. It seems to command silence and solemnifies the human-animal relationship.

The curators of this show are to be commended for sensitively organizing an exhibition that conveys not just the quantity and quality of Bonheur’s artistic production, but also her complex relationship with nature and its domesticated and wild beings, her transformation of masculine traditions, and her strength and perseverance. The design was filled with congenial spaces, well-chosen colors, and intimate viewing spots. There were wonderful pedagogical aspects. For example, a small, curved wall in the hallway included white, stenciled drawings of two stags and a measuring tape that allowed children to compare their own height to the enormous size of these animals. The exhibition closed with a triumphant account of Bonheur’s influence on US Western showbusiness and her connections to Buffalo Bill Cody. Upon exiting the show, viewers encountered Gloria Friedmann’s installation Come from Elsewhere (Venu d’Ailleurs, 2022), in which a stag made of soil and a conical mountain made of bark stand over a rectangle of leaves and in front of a circle of moss. This contemporary work makes Rosa Bonheur’s work seem even more compelling and necessary, as it conjures up our present relationship to nature, animals, ecology, and gender roles.

The catalogue for the exhibition has a physical presence commensurate to some of Bonheur’s most imposing paintings. Published only in hardback edition and in French, its cover is appropriately illustrated with Bonheur’s monumental King of the Forest. It contains a preface and introduction by the curators, four “parts” with short chapters, and appendices. More than twenty-two authors collaborated in the writing of the catalogue, a project that not only allows the reader to carefully study the works of art and related documents and photographs, but also incorporates perspectives from feminism, veterinary studies, music, photography, and the new materialism, to name a few of the approaches represented in it. Additionally, the essays consider traditions of animal painting outside of France (mainly in the UK and US), Bonheur’s role in the construction of a gendered art history, and her influences on artists past and present.

Part I of the catalogue, entitled “The Destiny of an Artist,” includes eight chapters that discuss Rosa Bonheur and her image: her biography as well as her self-construction and constructions of her. This section chronicles her most important personal relationships, from her origins in a household run by an artist-father to her connections to women around her, including her mother Sophie Bonheur, her friend and first companion Nathalie Micas, and her second companion, the US artist Anna Klumpke. There are also accounts of her artistic points of reference and knowledge of the Old Masters, as well as of her myth in the United States.

The second part, “Looking at the Living,” is shorter. It includes four chapters of varying length. Two of these chapters are dedicated to her breakthrough paintings as a young artist: Ploughing in the Nivernais and The Horse Fair. Another chapter explores Bonheur’s British inspirations, her reputation as a “female Landseer,” and her relationship to the Pre-Raphaelite painters. It also contains an interesting discussion of a canvas of Rosa Bonheur painting in the Highlands by Frederick Goodall from 1856–58, in which Bonheur is captured at work in situ with her painting box while cows graze next to her. The fourth chapter examines Bonheur’s animal portraits, remarkable for their verisimilitude and the psychological depth they lend to their subjects. The chapter considers these works both as portraits of the other and as empathic dialogues between the artist, the viewer, and the animal world.

Part III, entitled “The Making of the Work,” includes six short chapters that touch upon different subjects that relate to Bonheur’s practice. These include the reception of Bonheur’s work, aspects of the contemporaneous veterinary sciences, her outdoor painting processes, approaches to life drawing, and her work understood through other media such as prints and photographs.

Part IV, “Beyond Borders,” offers four chapters that examine Bonheur’s legacy as it extended transnationally and beyond her own lifetime: the long-term reception of The King of the Forest, her relationship to Buffalo Bill in Paris, related work by three US artists (Matilda Lots, Edward Mitchell Bannister, and Albert Bierstadt), and accounts of work from three contemporary artists that take up the themes of Bonheur’s work (Gloria Friedmann, Thomas Lévy-Lasne, and Anne-Charlotte Finel).

Closing the catalogue are five appendices: a very complete timeline of Bonheur’s life, a list of artworks exhibited, a select bibliography, an index of people’s names, and the photographic credits. The catalogue is a very valuable complement to the exhibition, as it constructs a larger, wider, and more complex view of Rosa Bonheur, both as a painter and a person. The exhibition undoubtedly captures the strength, energy, magnitude, and drive of this unique nineteenth-century female artist. The catalogue includes other aspects of Bonheur that would have been difficult to address in an exhibition but are necessary to broaden our understanding of her work. It is daringly interdisciplinary, drawing upon animal studies, material cultural studies, social and transatlantic histories, and gender studies as well as more traditional art historical approaches. Its brief but intellectually ambitious chapters address many diverse themes while remaining accessible to most readers. Both the exhibition and its catalogue provide a rich, graspable understanding of this extraordinary artist.