The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Frans Hals and the Moderns: Hals Meets Manet, Singer Sargent, Van Gogh

Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem

October 13, 2018–February 24, 2019

Related publication / exhibition magazine:

Marrigje Rikken et al.,

Frans Hals: Meet Singer Sargent, Van Gogh and Manet.

Haarlem: Frans Hals Museum, 2018.

106 pp.; more than 100 color and b&w illus.; partial checklist.

Available in Dutch and English.

€10 (soft cover)

ISBN: 978-94-90198-20-6

On August 30, 1880, the twenty-four-year-old John Singer Sargent signed his name in the visitors’ register of the Municipal Museum in the Dutch city of Haarlem. Sargent, then based in Paris, was touring the Netherlands to study the works of the great masters of the Dutch Golden Age, which were held in high regard at the time. Days earlier, he had written to his mother that he and his two traveling companions were planning to spend a week in Haarlem, where he wanted to “make a copy or two of Frans Hals.”[1] At the Municipal Museum, which had opened in 1862 in a few upper rooms in Haarlem’s Town Hall, the city’s rich art collections were on view. In addition to works by local masters ranging from Jan van Scorel to Johannes Verspronck, they included eight large group portraits of Haarlem civic guard companies and regents by Frans Hals (1582/83–1666), then a recently rediscovered master, whom Sargent admired but whose work he did not know well.

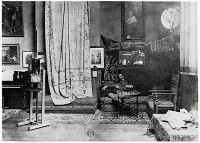

Haarlem’s spectacular Hals holdings, which were unlike anything Sargent had ever seen, must have come as a shock: among the paintings he encountered were, for example, Hals’s large dazzling banqueting pieces of the officers of Haarlem’s Saint George Civic Guard, portrayed in 1616 and again in 1627, as well as his last group portraits, also almost life-size, the moving Regents of the Old Men’s Almshouse and its exceptional pendant, the Regentesses, both painted ca. 1664 when Hals was about eighty-two years old. Hals’s grand works left an indelible impression on the young Sargent, who, two days after he had signed the museum’s visitors’ register, wrote to his family that he had “lost all count of the days” and could not possibly join them before another ten days or a fortnight for the holiday they had planned together.[2] He extended his stay in Haarlem, where he made at least four oil sketches and two drawings after Hals’s paintings.[3] Later, Sargent advised a pupil to visit the city (“There is certainly no place like Haarlem to key one up”), reportedly telling her to “[b]egin with Franz Hals, copy and study Franz Hals, after that go to Madrid and copy Velasquez, leave Velasquez till you have got all you can out of Franz Hals.”[4] Sargent would keep his youthful copies after Hals for the rest of his life: a photograph, taken a few years after his visit to Haarlem, shows the artist in his Paris studio, where a detail of two of the women depicted in the Regentesses appears on the back wall (fig. 1).[5]

Recently, two of Sargent’s works—his partial copy after Hals’s Regentesses, now in the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama, and his Standard Bearer, a figure from Hals’s Officers of the Saint George Civic Guard of 1627, now in a private collection in London—were temporarily returned to Haarlem. There, they are shown in close proximity to Hals’s originals, as part of an exhibition at the Frans Hals Museum, housed in the former Old Men’s Almshouse, where Haarlem’s art collections—including Hals’s paintings—have been on display ever since the Municipal Museum in the Town Hall closed its doors in 1913 (fig. 2). A third work by Sargent, one of the many society portraits he painted in the 1890s, Constance Wynne-Roberts (Mrs. Ernest Hill of Redleaf, died 1932) (1895; Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland), is included in the exhibition as well, showing that Hals continued to be a major influence on Sargent in his later career (see fig. 13).

The exhibition, titled Frans Hals and the Moderns: Hals Meets Manet, Singer Sargent, Van Gogh and organized by Marrigje Rikken, the Frans Hals Museum’s Head of Collections, brings together Hals’s paintings with the works of many later artists who were inspired by his art, thus exploring the old master’s deep and lasting impact on his modern counterparts. As the show makes abundantly clear, Hals was admired, idolized even, by numerous artists in the late decades of the nineteenth century, ranging from the three greats mentioned in the show’s title to divergent others including the Frenchman Antoine Vollon, the American-in-Paris Mary Cassatt, the German Max Liebermann, and the Belgian James Ensor. The exhibition, which is only shown at the Frans Hals Museum, is unabashedly ambitious, comprising about eighty paintings, including eleven from the museum’s own holdings, as well as some extraordinary international loans, among those Edouard Manet’s Boy with Pitcher (La Régalade) (1862/72; Art Institute of Chicago) and his Corner of a Café-Concert (probably 1878–80; The National Gallery, London); and Vincent van Gogh’s Postman Joseph Roulin (1888; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) and Madame Roulin and Her Baby (1888; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

As the exhibition underscores, the rediscovery of Hals—who was often portrayed as a dissolute drunkard after his style went out of fashion in the eighteenth century and more or less forgotten by the mid-nineteenth century—was largely due thanks to the efforts of one man: the French art critic Théophile Thoré (1807–69), who, in 1863, was one of the first connoisseurs to visit Haarlem’s newly established Municipal Museum.[6] At the time, Thoré signed the visitors’ register with his pseudonym, “W. Bürger”—the book, open to the page with his signature, is on view in the exhibition’s first gallery, a small tribute to Hals’s re-discoverer, who once wrote about the artist that “[a]ll his brushstrokes make their mark, aimed precisely and wittily where they should be” and that it seemed as if he “painted as if he were fencing and that he whipped his brush in the air as if it were a foil.”[7] (Nearby, another volume of the visitors’ register, dating to 1882 and open to the page with the signature of James McNeill Whistler, another noted Hals aficionado, is on display.)

Three years after his first visit, Thoré-Bürger returned to the Municipal Museum, and another two years later, in 1868, he published two pioneering essays on Hals and his work in the influential Gazette des Beaux-Arts.[8] It was in these writings that Hals was brought to international attention for the first time, and it was their publication that spawned the master’s revival—first, in the late 1860s, in France, and subsequently in the Netherlands and Germany, in other parts of Europe and in the United States.

Hals was initially, above all, a painter’s painter, admired by the artistic avant-garde in Paris not only for his virtuoso brushwork, his colorful palette, and the dynamic character of his compositions, but also for the allegedly authentic way in which he portrayed the people of his age. “[H]e painted portraits; nothing nothing nothing but that,” wrote Vincent van Gogh, Hals’s compatriot and one of his great admirers, in 1888 to his friend Emile Bernard. “Portraits of soldiers, gatherings of officers, portraits of magistrates assembled for the business of the republic, portraits of matrons with pink or yellow skin, wearing white bonnets, dressed in wool and black satin, discussing the budget of an orphanage or an almshouse,” van Gogh continued, “. . . he painted the tipsy drinker, the old fish wife full of a witch’s mirth, the beautiful gypsy whore, babies in swaddling-clothes, the gallant, bon vivant gentleman, moustachioed, booted and spurred. . . .”[9]

A few decades earlier, Thoré-Bürger had emphasized the linkage between the Dutch Old Masters and their modern counterparts in his writings. In his view, which was colored by his strong ideological republican convictions, the painters of Holland’s Golden Age had created an egalitarian art, an art that mirrored their egalitarian society and often ennobled the common man or woman—“a kind of photography of their great seventeenth century,” as he described it.[10] Still, the works of Hals and his contemporaries not only provided glimpses into Holland’s past, but also made one look forward to the future, Thoré-Bürger thought. As he wrote in 1868, in one of his groundbreaking essays on Hals, “These Dutch paintings representing the contemporary life of the artists very naturally make us dream of the art of our time.” Indeed, Thoré-Bürger encouraged the artists of his own day to do for their era what Hals and his Dutch contemporaries had done some two centuries earlier: paint their own time. He observed, “First, what occurs today will be history tomorrow.” And, he continued, “Who prevents one from making a masterpiece of a meeting of diplomats around a table, just as Rembrandt made a masterpiece of his Syndics of the Drapers’ Guild? Of a speaker at a parliamentary rostrum, a teacher surrounded by young people . . . or simply of men working at anything, or women having fun at anything?”[11]

Thoré-Bürger died in 1869, not long after the publication of his essays on Hals, but it was thanks to his efforts that the master’s star rose rapidly. Notably, it was in the year of Thoré-Bürger’s death that Paris’s Louvre acquired its first Hals, the lively, loosely painted Gypsy Girl (La Bohémienne, ca. 1628) as part of the great bequest of the physician Louis La Caze (1798–1869) (fig. 3). Hals’s painting—“a masterpiece improvised in a few hours of bright light and a good mood,” in Thoré-Bürger’s words—soon became a favorite with Paris’s artistic avant-garde, and as such it played a seminal role in Hals’s rehabilitation.[12] Regrettably, Hals’s original was not available for loan, but a copy, painted at the Louvre almost two and half centuries later by Max Liebermann, one of Hals’s most ardent admirers, makes for an appropriate substitute in the Haarlem exhibition (fig. 4). Several related works of “fallen women” are shown nearby, among these an exquisite van Gogh, Head of a Prostitute (1885; Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam) probably inspired by Hals’s “beautiful gypsy whore,” as van Gogh referred to the Louvre painting (figs. 5, 6).[13] Van Gogh’s haunting picture, with its thick and loose brushwork, not only refers to Hals, it also seems to look forward, reminding twenty-first century viewers of some of Lucian Freud’s portraits.

Soon after the Louvre acquired Hals’s Gypsy Girl, other museums started adding works by the artist to their collections. In 1874, Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie acquired its first four paintings by Hals in one fell swoop, when it purchased a substantial part of the splendid collection of one of Thoré-Bürger’s collecting friends, the industrialist Barthold Suermondt.[14] One of these was the celebrated Malle Babbe (1633–35), currently on view in Haarlem, together with the copy that Gustave Courbet, an early Hals enthusiast, painted in 1869 (figs. 7, 8; see also fig. 11).[15] (Interestingly, Courbet signed his copy after Malle Babbe twice—with his own signature and with a monogram resembling that of Hals.) Other museums soon followed and also began adding works by Hals to their collections, among these London’s National Gallery, which bought its first work by the master in 1876.[16]

It was also about this time, in the 1870s, that artists started traveling to Haarlem in remarkable numbers to study Hals’s works at the Municipal Museum in person.[17] After all, as the late Thoré-Bürger had observed, “Even the slightest painting by him is attractive and offers a lesson to artists. All aspects of his work are instructive, his faults as well as his strengths; for his faults are always those of a great practitioner.”[18] Manet, one of Thoré-Bürger’s many artist-friends, visited Haarlem in 1872, and made a small copy of Hals’s Regentesses (private collection, Italy; fig. 9). Untraced until recently, Manet’s painting—an unfinished sketch, measuring just 32.3 x 46 cm—came to light when a conservator working on it coincidentally contacted the Frans Hals Museum in early 2018, when it was in the process of organizing the present exhibition.[19] Manet’s sketch is now on view near Hals’s original and Sargent’s partial copy after the same painting. Another Frenchman who visited the Municipal Museum in 1872 was Antoine Vollon, whose full-size copy after Hals’s Officers of the Saint George Civic Guard of 1627, painted for the short-lived Musée des Copies in Paris, is now also on view in Haarlem (fig. 10). (Vollon’s copy is now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon.) And the list of visitors goes on: Mary Cassatt, aged twenty-nine, visited in 1873 (she copied Hals’s Meeting of the Officers and Sergeants of the Calivermen Civic Guard of 1633), while her compatriot William Merritt Chase visited in 1878, also at age twenty-nine, and many times thereafter. Notably, in 1903, Chase depicted himself as Colonel Johan Claesz Loo, one of the figures in Hals’s 1633 group portrait of the Calivermen Civic Guard—Chase’s fanciful Self-Portrait (The Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington) is also included in the present exhibition (see fig. 10).

However, the most frequent traveler to Haarlem was Max Liebermann, who paid countless visits from the early 1870s until the outbreak of the Great War, and who painted countless copies after Hals at the Municipal Museum. “When one sees Frans Hals, one gets the desire to paint, when one sees Rembrandt, one wants to give it up,” Liebermann is said to have remarked.[20] Among the circa thirty copies he made during the summer of 1876 alone is his Study of a Hand (Amsterdam, private collection), which depicts a detail of one of Hals’s grand group portraits, Officers and Sergeants of the Saint George Civic Guard (1639). Reportedly, it took Liebermann just about an hour’s time to finish his sketch.

Like Sargent, Chase, and other Hals admirers, Liebermann kept many of his youthful copies in his possession for the rest of his life; a photograph of 1932 shows the eighty-five-year-old Liebermann in his studio—his Study of a Hand after Hals, painted in Haarlem more than half a century earlier, is visible on a nearby table, behind several palettes and a vessel containing artist’s utensils and brushes.[21] In the present exhibition, Liebermann’s Study of a Hand is shown near Sargent’s and Manet’s copies after Hals (see fig. 2); as the display makes evident, each of these Hals adepts emphasized in their copies the qualities from the old master’s works that appealed most to their own artistic sensibilities, thus using Hals’s paintings as teaching tools to further develop their own distinctive styles. Liebermann’s Hals, therefore, is different from Manet’s Hals or Sargent’s Hals—or, for that matter, from Lovis Corinth’s Hals, as the latter’s thickly painted copy of Hals’s late Portrait of a Man in a Slouch Hat shows. Both Hals’s original and Corinth’s 1907 copy hail from Kassel, where they usually hang in different museum buildings—the Hals in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister; the Corinth in the Neue Galerie—but hang side-by-side in the Haarlem exhibition (fig. 11).

Of course, the Moderns not only made copies after Hals, but also used his paintings as an inspiration for some of their own works, both stylistically and thematically. Perhaps the most famous Hals-inspired work is Manet’s Le Bon Bock (Philadelphia Museum of Art), painted in 1873, not long after the artist’s visit to the Netherlands, where he saw Hals’s Merry Drinker (ca. 1628–30; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), then on view at the Trippenhuis in Amsterdam. Unfortunately, neither Hals’s Merry Drinker nor Manet’s Le Bon Bock was available for loan, but there is still much to enjoy in the exhibition. An unexpected stand-out picture is the Laughing Boy (Jopie van Slooten) (Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama), a spirited portrait of a Haarlem street urchin, painted in 1910 by Robert Henri, one of Hals’s many American admirers (fig. 12). Henri’s work clearly shows the influence of Hals’s portraits of children, several of which are displayed nearby.

As the Haarlem exhibition also shows, not every Hals-inspired effort was equally successful. What should one think, for example, of Liebermann’s 1891 life-size likeness of Hamburg’s mayor, Carl Friedrich Petersen, in the costume of a seventeenth-century Dutch burgher, complete with millstone collar, sword and oversize hat, and looking rather unhappy? (visible in fig. 13). Apparently, the mayor’s family took an immense dislike to the portrait—which pays equal tribute to Velázquez, another artist who greatly appealed to progressive taste in the late nineteenth century—and sold it soon after the sitter’s death. (The portrait is now in the Hamburger Kunsthalle.) Or, to give another example, what should one think of such Hals-inspired portraits as Frank Duveneck’s Man with a Ruff (ca. 1875; Collection of Dr. and Mrs. David A. Skier) and Ferdinand Roybet’s Portrait of the Painter Antoine Guillemet (date unknown; Musée Roybet-Fould, Courbevoie), both shown in the exhibition in the company of Pieter Jacobsz. Olycan (1629/30; Private collection, on long-term loan to the Frans Hals Museum) painted by the master himself? (see fig. 14). Here, as often, Hals wins by a long shot, and to a twenty-first century visitor, the two works by his admirers look somewhat over the top, as if they were trying to out-Hals Hals.

While the Haarlem exhibition is ambitious, the only publication that accompanies it is a bit less than what one would have hoped for. The Frans Hals Museum—the successor of the Municipal Museum, which played such an essential role in Hals’s rehabilitation and which is the current keeper of some of the master’s most magnificent works—decided not to bring out an exhibition catalogue, and thereby seems to be doing not only the scholarly community but also itself a major disservice. Instead, the museum offers what it describes as “a unique glossy”—that is, a soft-cover exhibition magazine of a little more than 100 pages, amply illustrated, and available in Dutch and English for the very reasonable price of ten Euros. In eighteen articles, each four to six pages long, the art of Hals and his later admirers is presented to the reader, with topics ranging from “The Rediscovery of a Genius” (by Marrigje Rikken, who authored most of the essays) and “Frans Hals According to Manet” (a fictional account by Ton van Kempen and Nicoline van der Beek) to “Breitner and the Modern Photographers” (Merel Bem) and “How Van Gogh Sunk His Teeth into Frans Hals” (Griselda Pollock). A quirky highlight is the six-page graphic novella by the young Dutch artist Aart Taminiau, which, under the title “Whistler does Haarlem,” tells the poignant story of the frail and elderly Whistler’s final pilgrimage to the Municipal Museum.

Admittedly, the magazine is an attractive and enjoyable read—breezy, fun and filled with anecdotes—and as such it succeeds in what seems to be its main purpose: to introduce the general museum visitor, who (supposedly) knows little about Hals and the Moderns, to the Old Master and to the many artists who were inspired by his works several centuries later. Needless to say, the Frans Hals Museum should be commended for this effort to bring Hals and the Moderns to the attention of a broad audience. Still, one wishes that there had also been a more substantial publication, one in which at least some of the research that was undoubtedly necessary to put this exhibition together would be presented and made available to interested scholars. Reportedly, the Frans Hals Museum is planning to publish a volume of scholarly essays based on the show at some point in the future. One very much hopes that this will indeed happen: an exhibition such as the current one, with its wonderfully complex and important theme, deserves a permanent record.

Frans Hals and the Moderns, although here and there uneven, is a significant show, and one that would well deserve a second and somewhat enhanced life elsewhere, preferably at a large institution that would be able to secure some of the works that are unfortunately absent in Haarlem—one thinks of several works by Hals that helped establish the artist’s reputation (the Gemäldegalerie’s Catharina Hooft and Her Nurse; the Louvre’s Gypsy Girl; the Rijksmuseum’s Merry Drinker; the Wallace Collection’s Laughing Cavalier) as well as some seminal Hals-inspired works (Philadelphia’s Le Bon Bock, and a few other good Hals-inspired paintings by Manet, Whistler, and Sargent). Nevertheless, the Frans Hals Museum deserves tremendous credit for organizing this attractive and thought-provoking exhibition, which succeeds at keeping the visitor engaged, asking him or her to look closely again and again, not only at the brilliant works of Hals, a seventeenth-century master who is in our own time once again all too often overlooked, but also at the works of the artists who, initially at Thoré-Bürger’s urging, helped bring Hals’s dazzling art back from oblivion some two centuries later. Manet, Sargent, Liebermann, van Gogh, and their contemporaries would have flocked to Haarlem to see this exhibition.

Esmée Quodbach

Assistant Director, Center for the History of Collecting

The Frick Collection, New York

e.quodbach[at]gmail.com

Translations are by the author unless otherwise indicated.

[1] Sargent’s letter to his mother and its contents are mentioned in a letter from his sister Emily Sargent to Vernon Lee, August 31, 1880. Cited in Richard Ormond and Elaine Kilmurray, John Singer Sargent: Complete Paintings, vol. 4, Figures and Landscapes, 1874–1882 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2006), 199. Sargent’s traveling companions were Ralph Wormeley Curtis and Francis Brooks Chadwick.

[2] Sargent’s letter, presumably again to his mother, and its contents are mentioned in a letter from his sister Emily Sargent to Vernon Lee, September 5, 1880, as cited in Ormond and Kilmurray, John Singer Sargent, vol. 4, 199.

[3] For Sargent’s oil sketches, see Ormond and Kilmurray, John Singer Sargent, vol. 4, 216–19, cat. nos. 739–42; for the drawings, see 201, figs. 110–11.

[4] Sargent to Julie Heyneman, as cited in Evan Charteris, John Sargent (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1927); see, respectively 140; 51. In July 1883, Sargent visited the Netherlands again. He may well have returned to Haarlem and the Municipal Museum, although his name is not recorded in that year’s visitors’ book. See Ormond and Kilmurray, John Singer Sargent, vol. 4, 200.

[5] After Sargent’s death in 1925, the copies were sold in London as part of his estate. A full copy of the Regents of the Old Men’s Almshouse remains untraced.

[6] For the rediscovery of Hals, see Frances Suzman Jowell’s “Thoré-Bürger and the Revival of Frans Hals,” Art Bulletin 56 (1974): 101–17; and “The Rediscovery of Frans Hals,” in Seymour Slive, ed., Frans Hals, ex. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts; Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art and Haarlem: Frans Halsmuseum, 1989), 61–86.

[7] Cited in translation in Richard Ormond and Elaine Kilmurray, John Singer Sargent: Complete Paintings, vol. 1, The Early Portraits (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998) 5. For the original text, see W. Bürger (pseudonym of Théophile Thoré), Galerie Suermondt à Aix-la-Chapelle (Brussels and Ostend: F. Claassen et Cie, 1860), 14. (“Tous ces coups de brosse marquent, lancés justement et spirituellement où il faut. On dirait que Frans Hals peignait comme on fait de l’escrime et qu’il faisait fouetter son pinceau comme un fleuret.”)

[8] W. Bürger (pseudonym of Théophile Thoré), “Frans Hals,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 24 (1868): 219–32; 431–48.

[9] Vincent van Gogh to Emile Bernard, undated letter [July 30, 1888]; letter no. 651. Cited in translation on http://vangoghletters.org/ (“il a fait des portraits, rien rien rien que cela. Portraits de soldats, réunions d’officiers, portraits de magistrats assemblés pour les affaires de la republique, portraits de matrones à peau rose ou jaune, de blancs bonnets coiffés, de laine et de satin noir habillées, discutant le budget d’un orphelinat ou d’un hospice. . . il a peint le buveur gris, la vieille marchande de poisson en hilarité de sorcière, la belle putain bohémienne, les bebes au maillot, le crane gentilhomme bon vivant, moustachu, botté et éperonné”).

[10] W. Bürger (pseudonym of Théophile Thoré), Musées de la Hollande, vol. 1 (Paris: Ve Jules Renouard; Brussels: Chez Ferdinand Claassen, 1858), 323 (“une sorte de photographie de leur grand xviie siècle”).

[11] Bürger, “Frans Hals,” 436. (“Ces tableaux hollandais représentant la vie contemporaine des artistes font songer aussi très-naturellement à l’art de notre époque . . . D’abord, ce qui est aujourd’hui sera de l’histoire demain; . . . Qui empêche de faire un chef-d’oeuvre avec une assemblée de diplomates assis autour d’une table, de même que Rembrandt a fait un chef-d’oeuvre avec ses Syndics de la corporation des drapiers? avec un orateur à la tribune des députés, un professeur au milieu de la jeunesse; . . . ou simplement avec des hommes qui travaillent à n’importe quoi, des femmes qui s’amusent à n’importe quoi?”).

[12] Bürger, “Frans Hals,” 444. (“un chef-d’oeuvre improvisé en quelques heures de vive lumière et de bonne humeur”).

[13] Ibid., Vincent van Gogh to Emile Bernard, undated letter [July 30, 1888] Letter 651.

[14] Singing Boy with a Flute (1627), inv. no. 801A; Malle Babbe (1633–35), inv. no. 801C; Portrait of a Man (1625), inv. no. 801F; Catharina Hooft with Her Nurse (1619–20), inv. no. 801G.

[15] Regrettably, Berlin’s enchanting Catharina Hooft with Her Nurse, which van Gogh used as a source of inspiration for his Madame Roulin and Her Baby, which is included in the exhibition, was not available for loan. Although a tiny image of the Berlin painting is included on the label for Madame Roulin and Her Baby, the latter looks a little lost in the exhibition without its seventeenth-century counterpart.

[16] Portrait of a Middle-Aged Woman with Hands Folded (ca. 1635–40); NG 1021; Lewis Fund, 1876.

[17] See Petra Ten Doesschate-Chu, “Nineteenth-century Visitors to the Frans Hals Museum,” in Gabriel P. Weisberg and Laurinda S. Dixon, eds., The Documented Image: Visions in Art History (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1987), 111–44.

[18] Cited in translation in Jowell, “The Rediscovery of Frans Hals,” 65. For the original text, see Bürger, Galerie Suermondt, 14. (“Il n’y a pas la moindre peinture de lui qui ne soit attirante pour les artistes et qui ne leur offre des enseignements. De lui, tout est insructif, ses défauts autant que ses qualités; car ses défauts sont toujours d’un grand practicien.”)

[19] See José Rozenbroek, “The Missing Copy by Édouard Manet,” in Marrigje Rikken et al., Frans Hals: Meet Singer Sargent, Van Gogh and Manet (Haarlem: Frans Hals Museum), 60–65.

[20] See Erich Hanke, “Mit Liebermann in Amsterdam,” Kunst und Künstler 12 (1914): 18. (“Wenn man Frans Hals sieht, bekommt man Lust zum malen, wenn man Rembrandt sieht, möchte man es aufgeben.”) Apparently, Liebermann made his remark after he had studied Rembrandt’s Night Watch in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum.

[21] For the photograph, see Rikken et al., Frans Hals, 17.