The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

March 12–July 29, 2018

Catalogue:

Colta Ives,

Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence.

New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 2018.

216 pp.; 172 color illustrations; notes, bibliography, index.

$50 (hardcover only)

ISBN 978-1-58839-584-9

The interconnections between horticulture and art are unfamiliar to most art historians, but the exhibition and catalogue Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence at the Metropolitan Museum of Art goes a long way towards remedying that oversight. We can thank Colta Ives, who after her retirement as distinguished print curator at the museum fulfilled a long-held interest in landscape architecture by obtaining a degree in the subject from Columbia University. This exhibition is the result of her partnership with Susan Alyson Stein, the museum’s Englehard Curator of Nineteenth-Century European Painting, with the assistance of Laura D. Corey, Research Associate in the Department of European Paintings; we are all beneficiaries of their joint endeavor. It is not a large show so it fits comfortably into the Lehman Wing’s temporary exhibition space where it has been elegantly installed by the Met designer Daniel Kershaw. Drawn almost exclusively from the Met’s collection and focusing on France in the period from the late eighteenth to the early twentieth century, it might be a small footnote on a major museum’s exhibition calendar, but because of the richness of the Met’s holdings, it is a small jewel, reminding us of the limitations of the “bigger is better” mantra of blockbuster shows.

Organized like a pinwheel around the Lehman Wing’s central courtyard, each section has a separate theme that parallels the essays in the catalogue. To walk through the exhibition is to relive the development of our modern environment where parks are open to all and private gardens are filled with myriad species both native and imported. The exhibition casts new light on works that took as their subject this new visual universe when gardening was being transformed from an aristocratic into a middle-class pursuit, when numerous public parks were being established, and when thousands of imported and hybridized flowers and trees were becoming familiar. To illustrate this new interest in horticulture, the show includes an extensive selection of visual culture, not just paintings, but also drawings, prints, and photographs, books and the illustrated press, film, art pottery, even garden tools, and ephemera such as trade cards, all of which serve to recreate the ambiance, the passions and pleasures of an earlier period. In its focus on the entire gamut of visual culture, it is an exhibition very much of the twenty-first century; not too long ago even the inclusion of photography on an equal footing with painting would have been considered daring.

The catalogue, which was authored by Ives, and the exhibition itself are so closely intertwined that they must be discussed together since each illuminates and completes the other. The catalogue introduction, “The Green Wave,” provides a brief overview of garden history beginning in the fifteenth century when Europeans embarked on voyages of discovery and returned bearing exotic botanic specimens. By the mid-eighteenth century, there was a virtual “green wave” of explorers such as Captain Cook in the South Pacific and Alexander von Humboldt in the Americas. Botany had become a science and garden design was in full swing with dozens of illustrated books and treatises published throughout Europe; many of these are on display in vitrines throughout the show.

The exhibition itself begins, appropriately enough, with the celebrated royal parks of Versailles and Saint-Cloud, designed in the severe formal symmetry of traditional French gardens, a style that reigned throughout Europe until the eighteenth century. The etching by Adam Perelle (two of his works are in the show) depicts Versailles, designed by André Le Nôtre for Louis XIV in 1661 (fig. 1). At the entrance to the first gallery is a spectacular Sèvres porcelain vase designed by Jean-François Robert showing the château and grounds of Saint-Cloud (fig. 2). The cold beauty of this garden style was challenged in the eighteenth century by a more natural relaxed manner developed in England, called picturesque or, in France, Anglo-Chinois. The catalogue’s second essay “Revolution in the Garden” clearly sets forth these two competing styles, and the gallery’s opposing walls face off with competing displays, the geometric versus the picturesque, each represented by prints, drawings, photographs, and books of engravings. We all know that ultimately the natural style won out, but as the catalogue points out, some striking examples of the French formal garden are still preserved today in the geometric designs of the parks of the châteaux of Fontainebleau and Versailles and in the Tuileries.

The more natural English style was championed by such formidable tastemakers as Queen Marie Antoinette who preferred it for her Trianon gardens at Versailles, and Empress Josephine who rejected the advice of the celebrated architects Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine and instead had her gardens at Malmaison designed in this style; Fontaine called it “disordered” (16). The English garden with its vast lawns and meandering paths set off by stands of trees became the new ideal, with the English designer Capability Brown spreading his gospel throughout the western world. In Paris this new aesthetic is apparent at the Parc Monceau and the Bagatelle, both designed by Thomas Blaikie, a disciple of Capability Brown. In the exhibition, the Anglo-Chinois style is represented by View in a Park by Alexandre-Hyacinthe Dunouy, an artist much in demand for his “portraits” of the private parks of his aristocratic patrons (fig. 3). The contributions of artists to landscape design was not limited merely to paintings, however; the catalogue details the contributions of François Boucher and Hubert Robert who planned the topography of many vast pre-Revolutionary estates. Unfortunately, few of these parks survived the 1789 Revolution. Several paintings by Boucher and Robert are in the museum collection but, unfortunately, were not included in the exhibition, although they do appear in the catalogue.

If topography is the macro of garden design, then the micro is flowers, and Empress Josephine, who dominates the “English wall” of the first gallery, is presented as the patron saint of horticultural arts in France, epitomized by the slightly over-the-top watercolor Allegory of Empress Josephine as Patroness of the Gardens at Malmaison by François Gérard (fig. 4). She had the largest collection of roses in Europe, and her desire to memorialize them led her to patronize Pierre-Joseph Redouté, one of the most gifted botanical illustrators. Six of his works are on display, including the colored stipple engraving Rosa turbinata from his collection Les Roses (fig. 5). Josephine’s taste for flowers inspired the custom, soon adopted by whomever could afford it, of bringing fresh-cut flowers indoors, ultimately encouraging a revival of flower painting, the focus of the last gallery of the exhibition. Josephine’s influence extended even to the manufacture of planters, several of which are included, and, as a lighter touch, the exhibition makes use of some out-of-the-way spaces for wall vitrines of gardening tools (fig. 6). Originally these were hand-forged and looked remarkably like modern sculpture; later in the nineteenth century, when their production had become a lucrative industry, their design was standardized.

“Parks for the Public” is the section of the show and essay in the catalogue which will be of great interest to nineteenth-century art historians, since we are so familiar with paintings taking public parks as their subject. Indeed, Ives points out that in Europe and America, the nineteenth century was the great era of public parks. Earlier parks and gardens had been reserved for aristocrats and royalty, but after the 1789 Revolution they were opened to all. The locked-down Gramercy Park in New York City is one of the few remnants of this earlier tradition. Versailles was renamed the Jardin national (national garden) and opened to the public, as were the Luxembourg Gardens and the Tuileries. The royal hunting forest of Fontainebleau became the first public nature preserve––and the site of the first French School of landscape painters, who established themselves at the village of Barbizon on the edge of the forest. Fontainebleau itself became a popular tourist site. The exhibition includes a wall of works done in and about the forest, anchored by Théodore Rousseau’s large painting of The Edge of the Woods at Monts-Girard, Fontainebleau Forest, and including several salted-paper prints of the forest by Gustave LeGray and Eugène Cuvelier, as well as three paintings by Corot, including his Fontainebleau: Oak Trees at Bas-Bréau, which he used as model for the copse in the Met’s Hagar in the Wilderness (1835) (figs. 7, 8, 9). Claude Monet’s Bodmer Oak (fig. 10) serves to remind us that the next generation of landscapists, the Impressionists, came of age in the forest of Fontainebleau, working alongside the older Barbizon artists.

In the Second Empire, Napoleon III and the Préfect of the Seine, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, transformed Paris itself, establishing parks at the four cardinal points: for the well-to-do there was the Bois de Boulogne in the west and the Bois de Vincennes in the east, for the working classes there was the Buttes Chaumont in the north and Parc Montsouris in the south. Altogether more than thirty public parks and neighborhood squares were established, old gardens were renovated, and new wide boulevards were planted with stately trees. To demonstrate the development of public parks, the exhibition includes a large digital map with each park identified by a period postcard superimposed over its location and appearing in chronological sequence. It is an eye-catching, innovative, educational tool that is also visually rewarding. Fortunately, we still can see it since it has been posted on the exhibition website: [https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2018/public-parks-private-gardens/related-videos]. Would that all digital museum displays should be so entertaining and informative at the same time. Kudos to those responsible: the map was designed by Susan Stein and Laura Corey (on the curatorial side), Melissa Bell and Bryan Martin (on the digital side), with contributions by Colta Ives and Kate Farrell.

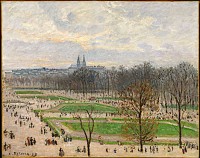

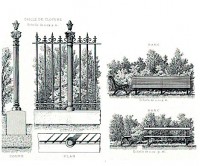

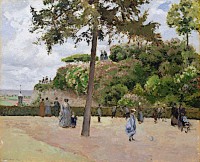

The Impressionists took Paris parks as their subject, just as the earlier generation of landscapists had worked in the forest of Fontainebleau. That much is well known, but what this exhibition reveals is how recent such possibilities were. Surely we will look with a fresh eye at Camille Pissarro’s paintings of the Tuileries, Gustave Caillebotte’s of Parc Monceau, or Eugène Atget’s photographs of the Luxembourg Gardens once we have seen them in this context (figs. 11, 12, 13). All these parks were renovated and replanted during the Second Empire, so their glories were still fresh and new. Both for these artists and for the Parisians who enjoyed their day in the park, the experience was newly minted. Even the parks’ iron fencing and iron benches were just becoming available in standardized designs, and the prints depicting them, cleverly installed nearby, remind us that, previously, these familiar urban commodities had to be individually commissioned and made-to-order (fig. 14). Public gardens were established not only in Paris, however; cities and towns throughout France (indeed, throughout the western world) were inspired to follow their example—Pissarro’s Public Garden at Pontoise is included in the exhibition to make just this point (fig. 15). Ives’ catalogue cites Frederick Law Olmsted’s and Calvert Vaux’s Central Park (1857), in this context, but, alas, neglects to mention their later creation of Prospect Park in Brooklyn (1866), widely considered an even greater achievement in the Capability Brown tradition (166–67).

Parallel to the development of public parks was the fashion for private gardens, not the landed estates of the pre-revolutionary aristocracy, but the more modest patches attached to middle-class dwellings. While trees lining the newly-built avenues were being planted, flowers were being introduced into gardens, new species like begonia or geranium that were not native to France. The catalogue essay “The Private Garden” chronicles this development, and the exhibition includes numerous related paintings along with drawings by Honoré Daumier that caricature the plight of the bourgeoisie who lacked a staff of professional gardeners. In one, a sweating bourgeois mops his brow and complains “I thought it would be more fun than this to water flowers during a heat wave!” (fig. 16). Monet’s Garden at Sainte-Adresse is one of the Met’s prize possessions; here it represents the epitome of the latest fashion in gardening, displaying the new and hybridized species of flowers in rainbows of color (fig. 17). Indeed, Monet was himself an avid gardener, as were Caillebotte and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Their penchant for gardening is apparent in the section of the exhibition and catalogue entitled “The Portrait in the Garden,” interpreted rather loosely to encompass figures with vases of flowers as well. Actually it should be titled “The Woman in the Garden” since men were so rarely depicted in this setting. Not only as models, however, women were also prominent among the artists exhibited because, although it would have been dangerous for a woman to set up an easel in public, she could do so safely in private spaces. A tour-de-force of the show is Berthe Morisot’s Young Woman Seated on a Sofa, which depicts a trifold passion for flowers: its subject is seated before masses of flowers, holding her chapeau decorated with artificial flowers, and posed on a divan upholstered in floral designs (fig. 18). Among the riches on display are four paintings by Morisot and two by Mary Cassatt, as well as Edouard Manet’s Monet Family in their Garden at Argenteuil (fig. 19). The catalogue here reverts to convention with an anodyne sentence or two about each work displayed, but no real analysis of the woman-equals-flowers analogy so conspicuous in this gallery. The only interpretation offered is: “The traditional affinity between women and flowers was an especially popular theme of story and song during the mid-nineteenth century” (110). Granted that this equivalence was then assumed to be “natural,” we are now in the twenty-first century when this subject matter looks—at best—quaint, and certainly merits a fuller discussion.

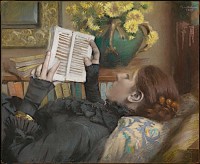

The last section of the exhibition is the gallery of still-life flower painting, discussed in the catalogue essay “The Revival of the Floral Still Life” that charts the progression of this motif (fig. 20). Ives recounts how the public sale of cut flowers and plants became established, progressing from street vendors to public markets and finally to the establishment of florist shops that appeared around mid-century. She points out that, throughout the nineteenth century, flowers advanced ever closer, from parks to middle-class gardens, and from gardens to houses where they appeared in bouquets real and painted, in fabric design, even on wallpaper. The numbers of floral still-life paintings in the Salons more than doubled in this period, one-third of which were by women artists. It should be noted, however, that despite its ubiquity, flower painting as a subset of still-life always ranked lowest in the academic hierarchy, below even landscape painting and certainly below the categories of history or genre painting that depicted the human figure. And perhaps women artists’ preference for the subject is another reason why it continued to be accorded such low status. Inexplicably, the exhibition elides this reality, the catalogue pointing out that Gustave Courbet did dozens of floral subjects but failing to note that, in fact, he instructed his dealer to exhibit and sell them anonymously because he didn’t want to be known as a flower painter (133–34). Despite Courbet’s reluctance, the gallery includes splendid works by artists from Eugène Delacroix to Henri Matisse, as well as photographs by Charles-Hippolyte Aubry and Adolphe Braun (fig. 21). Of course, the Met included its celebrated Edgar Degas A Woman Seated Beside a Vase of Flowers, but the exhibition also features intriguing lesser-known works, such as Albert Bartholomé’s The Artist’s Wife Reading, whose skewed point-of-view throws the viewer slightly off-balance (figs. 22, 23). Mary Cassatt’s Lilacs in a Window is an unfamiliar painting by a much better-known artist and presents such a perfectly balanced image of purple blooms against the green geometry of the window frame that we regret that she did not paint more still life; perhaps she was all too cognizant of the expectation that still life would be the “normal” specialization of a female artist (fig. 24). This section of the exhibition also includes vases and jardinières made by artists such as Ernest Chaplet and Emile Gallé; they provide a striking visual counterpoint to the paintings and photographs on the gallery walls (fig. 25).

One of the exhibition’s most innovative features is the transformation of the central courtyard into a French conservatory garden with a central fountain surrounded by potted plants and trees. The green iron benches installed here are familiar to Parisians and visible in many of the nearby paintings. They provide museum visitors with a welcome moment of repose, and the setting brilliantly transports us into the ambiance of the works in the surrounding galleries as we and our neighbors are transformed into “portraits in the garden.” Two brief films playing on monitors just outside this central court augment the experience. Louis Lumière’s L’Arroseur arrosé (The Sprinkler Sprinkled) of 1895, the earliest film comedy, is an amusing bit of slapstick involving stepping on a garden hose and getting drenched; Sacha Guitry’s 1915 Those of Our Land (Ceux de chez nous), provides a more serious note, showing Monet painting in his garden at Giverny, the subject of several of his paintings installed nearby (fig. 26). The Met has posted these films online so even those who miss the exhibition can see them: [https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2018/public-parks-private-gardens/related-videos].

If the Empress Josephine introduced the exhibition, then Monet closes it; virtually an entire gallery is devoted to his work (fig. 27). With more than forty varieties of iris at Giverny, and an entire staff of professional gardeners, for him flowers, whether planted or cut and arranged as an indoor subject, became the vehicle through which he expressed his aesthetic ideas. Thirteen of his paintings in the exhibition span several different galleries and categories, from Barbizon to floral still-life. As he himself wrote, “My garden is my most beautiful work of art” (105).

Once the exhibition has ended, we will have only the catalogue to remember it by, but it is a publication that should be in all libraries. To write a series of cogent essays on a theme displayed primarily by works in a museum’s collection is a remarkable accomplishment, and Ives’s essays should be required reading for all nineteenth-century art historians. They are beautifully written, argued and illustrated, and teach us much about the art and cultural history of the period while giving us a visual and intellectual feast. As does the exhibition itself.

Patricia Mainardi

Graduate Center, City University of New York

Pmainardi[at]gc.cuny.edu