The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

While the early reception of French impressionism in the United States has been studied in depth from the vantage point of the East Coast, the movement’s impact outside of this area has not benefited from the same scrutiny.[1] Thus, art historians generally have overlooked the uncommonly appreciative stance of midwestern museums with regard to the initially controversial school.[2] Nor have they fully understood the role of these museums in institutionalizing impressionism because, unlike the galleries and auction houses that promoted impressionism on the East Coast, their focus was on elevating impressionist paintings as works of art rather than as commodities for sale to private collectors.

This article bolsters the above argument by way of a case study, focusing on the 1907–8 exhibition of impressionist art that traveled to seven cities across the United States (Buffalo, New York; St. Louis, Missouri; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Cincinnati, Ohio; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Saint Paul, Minnesota; Milwaukee, Wisconsin). Although Durand-Ruel & Sons, the New York branch of the Parisian art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831–1922), had loaned the majority of the works to the exhibition with the ambition of selling the pieces to the exhibiting institutions or to local art collectors, the show traveled strictly to educational venues—museums, libraries, and art guilds. With sixty-three to eighty-eight pieces on display per show, the exhibition presented the public with a comprehensive array of French impressionist paintings in a context in which their art-historical rather than their commercial value was highlighted.[3] An analysis of the 1907–8 exhibitions’ catalogues, press articles, and their related correspondence reveals the crucial role of midwestern museums in shaping the US reception of French impressionism at the beginning of the twentieth century and in developing a distinctly US relationship with the movement.

French Impressionism’s Early Exposure in the United States

The first official French impressionist exhibition in the United States opened at New York City’s American Art Association in April 1886 when James Sutton, one of the founders of that gallery-cum-auction house, and Paul Durand-Ruel coordinated to introduce the movement to the people in the United States. Prior to this exhibition, select pieces had been included in earlier US shows: Louisine Havemeyer had loaned Edgar Degas’s A Ballet (1876; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City) to the 1878 American Watercolor Society exhibition; Durand-Ruel had lent several pictures to the Official Foreign Manufacturer Fair in Boston in 1883; that same year the Pedestal Fund Exhibition in New York had included pieces by Degas and Édouard Manet. However, it was Works in Oil and Pastel by the French Impressionists, the first official showing on US soil that ran from April to May 1886 and later moved to the New York City’s National Academy of Design with additional art pieces, that definitively established the reputation of French impressionism in the United States. Once Sutton succeeded in securing government approval to categorize the works as educational in value, the pieces could enter the country tariff-free.[4] Thus, the art movement quickly gained in popularity and stature.

In 1887, the French dealer Paul Durand-Ruel opened a New York City gallery at 297 Fifth Avenue named Durand-Ruel & Sons; two years later, in September 1889, it moved to 315 Fifth Avenue, and finally, in 1894, to 398 Fifth Avenue. The gallery was managed by his sons, Charles, Joseph, and Georges.[5] Wishing to reach an ever-widening audience, the gallery organized exhibitions in venues outside of New York City, which were supervised by Russell Spaulding, a gallery employee. These venues included J. Eastman Chase in Boston, J. J. Gillepsie in Philadelphia, Noonan-Kocian in St. Louis, and W. Scott Thurber in Chicago.[6]

Why Durand-Ruel & Sons increasingly sought out the Midwest as a new market at the turn of the century remains uncertain. The growing interest in French impressionism fostered by the 1893 Loan Exhibition at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago may have been a factor. Jennifer A. Thompson speculates that it is also possible that collectors encouraged the dealer to reach out to a broader market. She suggests, for example, that Alden Wyman Kingman, a patron who lived in Colorado in the 1890s, possibly gave Durand-Ruel the idea to organize an exhibition in Colorado, which led to the 1897 showing of several impressionist paintings at the Brown Hotel in Denver.[7] The gallery also seasonally rented railroad cars to take its inventory to cities such as Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Toledo, Chicago, Minneapolis, and St. Louis, where it exhibited the works in hotels. This enabled midwestern collectors to purchase pieces without traveling to New York City.[8] A final and important reason for Durand-Ruel’s expansion of its business in the Midwest was the fact that the New York market for impressionism had become increasingly crowded with dealers, including L. Crist Delmonico, M. Knoedler & Co., Isidore Montaignac, and Sutton. Seeing an opportunity for sales elsewhere, Durand-Ruel & Sons seized it, knowing that their sizable stock allowed them to loan paintings to several exhibitions simultaneously—something most other dealers could not do.

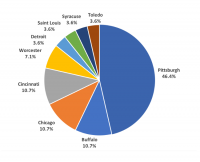

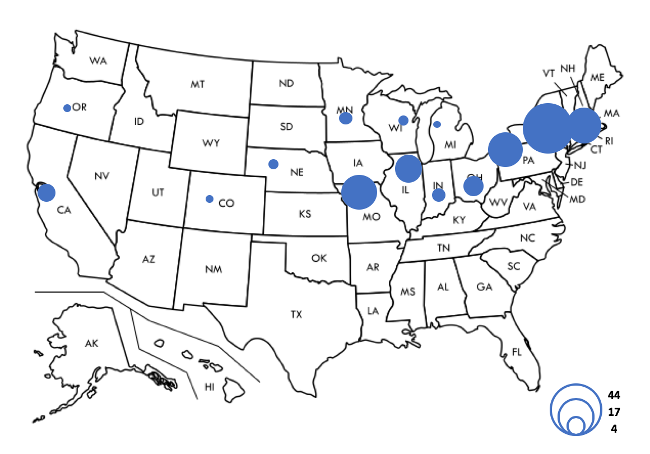

As mentioned above, the reception of impressionism in the Midwest was different from its reception on the East Coast, in that paintings were primarily shown in museums rather than commercial galleries or auction houses. From 1886 to 1908, roughly 23 percent of the 119 exhibitions countrywide (fig. 1) featuring at least one French impressionist piece were held in museums. During this same period, over 45 percent of museum exhibitions including French impressionist pieces were held in Pittsburgh, thanks in part to the Carnegie Institute’s annual exhibition. Next, Buffalo, Chicago, and Cincinnati each accounted for roughly 10 percent of museum shows, followed by other eastern and midwestern cities (fig. 2).

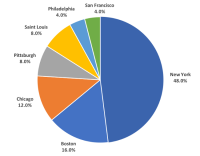

East Coast exhibitions containing impressionist paintings often tended to be in galleries. Of all the gallery exhibitions in the United States between 1886 and 1908, 48 percent were in New York, followed by Boston and Chicago (fig. 3). These numbers reflect the strength of these three cities as art markets, but they also explain how impressionism permeated US culture differently in the Midwest than on the East Coast. Simply put, East Coast cities had more commercial galleries than museums; midwestern cities had very few commercial galleries, but most of them had museums or related educational venues.

The 1907–8 Traveling Exhibition

The 1907–8 traveling exhibition prided itself on being the largest showing of impressionist pieces in scope and size ever held in the country, yet it was probably groundbreaking only in the fact that an exhibition of this magnitude was organized in a museum.[9] The 1886 exhibition at the American Art Association included more pieces by the French school than the 1907–8 traveling exhibition, and Durand-Ruel regularly hosted one-person or group showings of impressionist painters at his New York City gallery starting 1892. That is not to say that East Coast museums never showed French impressionist pieces. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston purchased Degas’s Racehorses at Longchamp (1871) in 1903 and the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Madame Georges Charpentier and Her Children (1878) in 1907, but neither organized temporary exhibitions of the artists’ works until later. Even considering these East Coast acquisitions, more midwestern museums included French impressionist pieces proportionally in their exhibitions than their East Coast counterparts.[10]

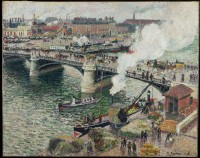

Indeed, the public in most of the seven stops of the exhibition had already been exposed to French impressionism prior to the 1907–8 show, although on a much smaller scale than people in East Coast cities and Chicago. The inhabitants of St. Louis and Pittsburgh were most familiar with impressionism. The St. Louis Annual Music Hall Exposition occasionally included paintings from the French school.[11] French paintings could also be seen in the Noonan-Kocian Gallery and the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition.[12] In Pittsburgh, the Carnegie Institute started to incorporate pictures from the movement into its annual exhibitions as early as 1896 and even purchased Camille Pissarro’s The Bridge, Rouen (1896) and Alfred Sisley’s View of Saint-Mammès (ca. 1881) in 1899.[13] In Buffalo, the Albright Art Gallery’s director, Charles M. Kurtz (1855–1909), became knowledgeable about the French school after assisting Halsey Ives with the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition’s Loan Collection of Foreign Masterpieces Owned in the United States and later as the director of the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition. In addition, midwestern patrons including James J. Hill of St. Paul and William Rockhill Nelson of Kansas City each owned impressionist pieces in the mid-1890s.[14] Thus, by 1907 the public in these midwestern cities knew of French impressionism thanks to prior commercial and educational shows as well as local collections, but they had never been exposed to the movement broadly speaking.

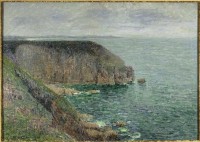

The 1907–8 impressionist exhibition stopped in seven different locations: the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, Albright Art Gallery from October 31 to December 8, 1907;[15] the St. Louis Museum of Fine Arts starting December 19, 1907;[16] the Carnegie Institute from February 10 to March 10, 1908 (fig. 4);[17] the Cincinnati Museum from March 18 to April 12, 1908;[18] the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts at the Public Library Building of Minneapolis from April 23 to May 6, 1908;[19] the Arts Guild in St. Paul from May 13 to May 23, 1908;[20] and the Wisconsin School of Art from May 31 to June 13, 1908.[21] A center core group of paintings, which included paintings by Eugène Boudin and John Lewis Brown, often seen as precursors to impressionism, as well as followers like Maxime Maufra and Gustave Loiseau, remained the same in the various locations (fig. 5). In two locations, Minneapolis and St. Paul, the exhibition also included paintings by six US artists residing in Paris. Moreover, institutions often altered the show’s name: the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, the Carnegie Art Institute, and the Cincinnati Museum entitled the show an Exhibition of Paintings by the French Impressionists, while the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts called it A Special Exhibition of Selected Paintings by the French Impressionists.

By 1907, many midwestern cities had increasingly used traveling exhibitions to bring quality pieces to their institutions while limiting their expenses. Examples of traveling exhibitions are numerous. The Society of Western Artists, for example, often toured midwestern towns, including Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Detroit starting in 1902.[22] Likewise, in 1916 paintings from San Francisco’s Panama Pacific International Exposition traveled to the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Chicago Art Institute, the St. Louis Museum of Fine Arts, the Toledo Museum, and the Detroit Museum of Art thanks to collector and museum loans. A letter from the Carnegie Institute archives from May 29, 1915, highlights that “at the meeting of the American Federation of Arts, held in Washington . . . a number of officials of the middle western Museums discussed a cooperative scheme whereby exhibitions of magnitude could be assembled and by passing them from one Institution to the other much labor and expense could be saved.”[23] The 1907–8 traveling impressionist exhibition grew out of this common practice of circulating pieces from one museum to another. Unlike other traveling museum shows, however, the paintings were not loaned from an artist’s society, but rather almost exclusively from one art dealer.

The midwestern venues that hosted the Durand-Ruel exhibition were, for the most part, newly founded museums: the St. Louis School and Museum of Fine Arts (1881), the Carnegie Institute (1895), the Cincinnati Museum (1881), or the forerunners of museum yet to be founded, such as the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts (1883), the St. Paul Arts Worker’s Guild (1902), and the Wisconsin School of Art, also known as the Milwaukee Art Students League (1896). The Albright Art Gallery had recently merged with the Academy of Fine Arts of Buffalo in 1905.[24]

Though some museums were approached by a representative of Durand-Ruel, others contacted the gallery as they heard of the exhibition and wanted their city to benefit from the show. John W. Beatty (1851–1924), director of the Carnegie Art Institute, wrote to Durand-Ruel & Sons on January 6, 1908, asking: “Are you willing to help us arrange a group of seventy-five to one hundred very important works? Mr. Holsten said the collection at St. Louis would be free about the end of this month.”[25] Likewise, a letter from the Cincinnati Museum archives from January 6, 1908, shows that Joseph Henry Gest (1859–1935), curator of the museum, asked Durand-Ruel for the impressionist paintings. Durand-Ruel replied: “I will be very pleased to let you have the collection of Impressionist pictures now in St. Louis. I have already engaged myself with Mr. Beatty of Pittsburgh to let him have the collection after the exhibition will be over in St. Louis and could let you have it after the exhibition will be closed. I could not tell you just now the exact date and am writing to Mr. Beatty to find out.”[26] In the following letter, dated January 17, 1908, Durand-Ruel mentions that the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts also asked for the paintings, as the dealer answered: “I have received an application for the same pictures from Mr. Robert Koehler, Director of the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, and I wrote to him that I would be very pleased to let him have the pictures later in the season as you had already asked me for them.”[27] As this correspondence demonstrates, the institutions often contacted the gallery to obtain loans and were not unwillingly lured into a commercial show.

The fact that the impressionist exhibitions were held in museums or educational institutions does not mean that their organizers lacked commercial ambitions. Many of the exhibition catalogues specified that the pieces came from the Durand-Ruel gallery and were for sale. Exhibition titles never mentioned the loans’ provenance, but exhibition catalogues often mentioned it, likely to legitimize the selection, as Durand-Ruel was renowned. For instance, the Albright Art Gallery’s publication informed the viewers that “most of these paintings are for sale” and recommended potential buyers to “apply to the Assistant Secretary . . . for prices and other information.”[28] Similarly, the Carnegie Institute catalogue mentioned that Durand-Ruel & Sons had loaned the pieces without specifying that they were for sale.[29] The Cincinnati Museum’s catalogue also stated that “the present collection, which for the time in Cincinnati represents comprehensively the French impressionist painters, is lent by Messrs. Durand-Ruel and Sons and by Mr. George Durand-Ruel of New York City.”[30] The Cincinnati Enquirer also disclosed the dealer’s identity.[31] While on view at the Minneapolis Public Library Building, newspaper articles omitted Durand-Ruel’s name, even the extensive one written by Elizabeth Chant in the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune.[32] That same venue’s exhibition catalogue stated that the “Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts is indebted to the firm Durand-Ruel & Sons of New York, for the privilege of exhibiting the remarkable collection of works by the French impressionists.” A few pages later, organizers informed the readers that the pieces were for sale.[33] The same catalogue’s preface, written by Robert Koehler (1850–1917), does mention the exhibition’s relationship to Durand-Ruel & Sons.[34] The conclusion we can draw from all this is that most museums realized that it was important to mention Durand-Ruel’s name because it served to legitimize the selections, but that it was equally important not to mention it too much so as to underplay the exhibitions’ commercial thrust.

Displaying French Impressionism

Only 40 percent of the pieces shown came from what foundational texts consider impressionist painters: Degas, Manet, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley.[35] Discrepancies in asking prices, apparent in the priced exhibition catalogues from the Albright Art Gallery and the Cincinnati Museum, highlight the inconsistent reputations of the artists Durand-Ruel represented. Paintings by Albert André, Georges d’Espagnat, Loiseau, and Maufra ranged from $200 to $500, while those by Degas, Manet, Monet (fig. 6), and Renoir went from $1,700 to $14,000.[36] Such high prices, especially for the core impressionists, translated into few purchases by local collectors or museums.[37]

As was common in shows of the time, the exhibition also included paintings by artists not typically considered impressionists, such as John Lewis Brown, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and Johan Barthold Jongkind. The art critic Mariana Van Rensselaer questioned the reason of their addition during the 1886 exhibition and postulated, “just why [Durand-Ruel] added the pictures to which I refer, I cannot positively say; perhaps because he thought something good and attractive, and not unfamiliar, would predispose our minds to seeing excellence in the unfamiliarity which lies around them.”[38] Perhaps the 1907–8 exhibition, mounted some thirty years later, included Brown and Jongkind—more commonly accepted artists—to ease the public into more radically new art.

The Carnegie Institute catalogue’s introductory statement, written by Beatty, reveals a preference for some artists, most often the core impressionists. Beatty wrote almost exclusively about Monet until the very last paragraph of his statement, in which he mentioned that “the power of a Monet, a Degas, a Renoir, a Sisley, a Cassatt, or a Boudin, should not be confounded, even by the layman, with the multitude of incapable imitators.”[39] His emphasis on Monet, and to a lesser extent on Eugène Boudin, Mary Cassatt, Degas, Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley, highlights his higher esteem for these artists. Similarly, in her review in the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune Chant focused on Manet, Monet, Degas, Pissarro, Cassatt, and Chavannes.[40]

Most pictures by the French impressionists on view were painted in the 1880s and 1890s. The oldest piece dated from 1865 (Manet’s Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers) and the most recent from Monet’s Charing Cross Bridge series (1899–1904). The pieces by the six impressionist artists mentioned above (Degas, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley) highlight a strong preference for landscape scenes: 45 percent of the paintings shown were landscapes, a figure that would be even higher if we included the 13 percent of cityscapes (fig. 7). Less than 25 percent of the impressionist paintings in the exhibition were portraits, and the remaining were still lifes and figure scenes.[41] Monet, the most promoted artist of the French impressionists, boasted the biggest showing with 27 percent of the paintings by the school, followed by Renoir and Sisley with 21 and 18 percent respectively.

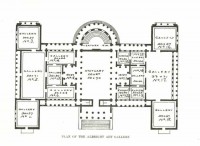

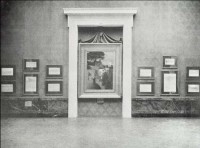

How the venues displayed the pieces remains difficult to discern, as few photographs exist. Most often, the layout did not differentiate the core impressionists from their predecessors or their followers. The Buffalo Fine Arts Academy’s December 1907 issue of Art Notes indicates (figs. 8, 9) that gallery twelve showed pieces by Victor Pierre Huguet, gallery thirteen displayed some Monets and a Renoir, gallery fourteen featured Manet’s Portrait of Faure (fig. 10) and Degas’s Portrait of a Man (1866; Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn), as well as pieces by Boudin and Stanislas Lépine, and gallery fifteen held three more paintings by Monet.[42] Likewise, the Milwaukee Journal article detailing the exhibition’s stop at the Wisconsin School of Art asserts that “several of the artists with pictures in the collection are represented in both rooms and the contrasts shown in their work along these different lines is in many cases remarkable.”[43] These comments insinuate that pieces by famed impressionists and less popular artists hung side by side, as the rooms were divided into “tone work” and “colorist” pieces instead of by school. Only the Carnegie Institute seems to have hung all pieces by one artist next to each other.[44] Although Monet was often the best represented, he did not always receive the most coveted position, as a Buffalo Morning Express article suggests that Manet’s piece Ecce Homo [Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers] “occup[ied] the window panel in the gallery no. 2” but could also be “seen across the white vistal of the sculpture court.” Consequently, it was regarded as “the dominating picture in the gallery.”[45]

The Traveling Exhibition’s Broader Impact

Midwestern critics wrote mostly positive reviews for the 1907–8 traveling exhibition, helping increase the movement’s fame in local cities.[46] Minneapolis Sunday Tribune art critic Chant asserted that “in the notable collection now on view at the Public Library, the leading exponents of this method are represented. This is undoubtedly the most interesting exhibition that has been shown in Minneapolis for a very long time.”[47] Likewise, a Cincinnati Enquirer reporter remarked that “considerable interest is being aroused among art lovers and patrons of this city by the announcement of the exhibition of paintings by French Impressionists to be held at the Art Museum in Eden Park. . . . [T]he display is said to be the finest ever shown in this country.”[48]

Decidedly, through its scope, positive critical reception, and context, the 1907–8 exhibition helped impressionism enter the art-historical canon. The exhibition catalogues fostered a distinctly US reaction to impressionism by defining the school in terms that resonated with US viewers’ preferences. These publications championed the impressionists as formerly under-appreciated artists who fought for recognition. The Cincinnati Museum catalogue reminded the viewer of “the bitter criticism of the French Ministry of Fine Arts for accepting the Caillebotte Collection of Impressionist art as a gift to the Luxembourg [Museum].”[49] It also informed readers of “a sympathetic spirit of independence [that] held [the impressionists] together, a protest against academic routine and against government patronage.”[50] Similarly, the Minneapolis Society of Fine Art’s exhibition catalogue stated:

It is an old story, that struggle for new ideas, and complete victory is seldom vouchsafed the fighters during the prime of their lifetime. It speaks well, therefore, for the justice of their cause and also for the progress of broad and liberal views in art-appreciation generally, that this group of artists has been allowed to reap the benefit of their labors while they are still able to enjoy them to the full, for such is rather the exception than the rule with artists who seek new and untried modes of expression.[51]

Such comments emphasizing the impressionists’ fight against convention likely appealed to US spectators. As Richard Brettell argues, “Impressionism was associated with two things in America: rebelliousness and modern independence from authority—both of which play a fairly strong role in the American character, whoever defines it.”[52] As such, the organizers defined and described impressionism in a way that resonated with US viewers, namely by mentioning the school’s rebellion against convention.[53]

Events organized around the museum exhibitions also encouraged viewers to more fully engage with the pieces in ways less commonly seen in conjunction with gallery shows. Museum talks were often given to foster a better understanding and appreciation of the movement.[54] The Carnegie Institute even provided a list of publications available at the Carnegie Library.[55] In some venues, museums motivated children to make their own interpretations of the movement. For example, in Minneapolis, “to stimulate interest among the school children in these pictures,” two five-dollar prizes were offered, one to a high school and one to an elementary school student, to whoever wrote “the best essay on any picture which the contestant may select.”[56] These various events, common in educational venues more than in commercial ones, provided the groundwork for midwestern visitors of all ages to develop a personal relationship with the pieces.

Conclusion

This case study of the 1907–8 traveling exhibition organized by Durand-Ruel in the Mid-West of the United States refines our understanding of the way in which French impressionism “conquered” the United States in the early twentieth century. As we have seen, the exhibition was the joint outcome of the French dealer Paul Durand-Ruel’s desire to reach a broader US market and the eagerness of mostly young midwestern museums to display quality works. Through Durand-Ruel’s initiative, French impressionism reached seven midwestern cities by means of exhibitions in museums or other educational venues that ranged in numbers from sixty-three to eighty-eight paintings. By being exhibited in cultural rather than commercial spaces, impressionist paintings in the Midwest were appreciated and interpreted as historical and aesthetic objects rather than commodities, conferring credibility on the impressionist movement and helping it enter mainstream US culture.

I would like to thank Meg Black (Minneapolis Institute of Art), Gabrielle Carlo (Albright-Knox Art Gallery), Jennifer Hardin (Cincinnati Art Museum), and Norma Sindelar (St. Louis Art Museum) for their invaluable help. I am also grateful to Penny Finocchiaro, to the anonymous peer reviewer, and to Petra Chu for their insightful comments and suggestions.

[1] Publications on French impressionism in the United States include Sylvain Amic, ed., L’Impressionnisme, de France et d’Amérique: Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Degas, exh. cat. (Versailles: Artlys, 2007); William H. Gerdts, American Impressionism, exh. cat. (Seattle: Henry Art Gallery, 1980); William Johnston, “Alfred Sisley and Early Interest in Impressionism in America, 1865–1913,” in Alfred Sisley, 1839–1899, ed. Mary Anne Stevens, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 55–70; Michael Leja, “Monet’s Modernity in New York in 1886,” American Art 14, no. 1 (Spring 2000): 51–79, doi:10.1086/424351; Sylvie Patry, ed., Paul Durand-Ruel, le pari de l’impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Paris: RMN Editions, 2014); Eric M. Zafran, “Monet in America,” in Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, ed. Joseph Baillio (New York: Wildenstein, 2007), 80–152.

[2] Several negative comments were published on impressionism in the last decades of the twentieth century in the United States. See, for example: “Paintings for Amateurs,” New York Times, April 10, 1886, 6; Charles Henry Hart, “Fine Arts: The Pennsylvania Academy Exhibition,” The Independent, March 5, 1891, 22. Even at the turn of the twentieth century, some critics considered it a superficial movement. See, for example, John B. Longman, “Art and Artists,” The Tennessean, October 28, 1900, 24, https://www.newspapers.com/ [login required].

[3] The first official exhibition of the French impressionists at the National Gallery of Art and the National Academy of Design included more pieces.

[4] Jennifer A. Thompson, “Paul Durand-Ruel et l’Amérique,” in Paul Durand-Ruel, le pari de l’impressionnisme, ed. Patry, 107–20.

[5] Thompson, “Paul Durand-Ruel et l’Amérique,” 117.

[6] Alison McQueen, “Private Art Collections in Pittsburgh: Displays of Culture, Wealth, and Connoisseurship,” in Collecting in the Gilded Age: Art Patronage in Pittsburgh, 1890–1910, ed. Gabriel P. Weisberg, exh. cat. (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1997), 57–58; Thompson, “Paul Durand-Ruel et l’Amérique,” 117–20.

[7] Thompson, “Paul Durand-Ruel et l’Amérique,” 118.

[8] Richard Brettell, “Impressionnisme: Capitalisme et collectionneurs dans le contexte national américain,” in L’Impressionnisme, de France et d’Amérique Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Degas, ed. Amic, 33.

[9] “Notable Collection of 90 Canvases on View at Carnegie Institute,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, February 11, 1908, 2.

[10] The Chicago Art Institute hosted exhibitions of paintings by Claude Monet and Édouard Manet in 1895. Gloria Lynn Groom and Douglas W. Druick, eds., The Age of French Impressionism: Masterpieces from the Art Institute of Chicago (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 12–13.

[11] Before the 1907 traveling exhibition, the Saint Louis Annual Music Hall Exhibition hosted one or more impressionist pieces in 1890, 1893, 1894, 1895, 1896, 1897, and 1898.

[12] Founded in 1893, the gallery started including impressionists paintings in its shows as early as 1905. For more on St. Louis collections, see Julie A. Dunn-Morton, “Art Patronage in St. Louis, 1840–1920: From Private Homes to a Public Museum” (PhD diss., University of Delaware, 2004).

[13] Neil Kenneth, A Wise Extravagance: The Founding of the Carnegie International Exhibition, 1895–1901 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996), 39.

[14] Hill purchased a Renoir, Landscape of the Côte d’Azur (Tamaris) from Durand-Ruel on March 19, 1892, and Nelson purchased a Pissarro, Eragny, Sun Setting, in 1896. Janet Lynn Whitmore, “Painting Collections and the Gilded Age Art Market: Minneapolis, Chicago and St. Louis, 1870–1925” (PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 2002), 69.

[15] Catalogue of an Exhibition of Paintings by the French Impressionists, exh. cat. (Buffalo: Buffalo Fine Arts Academy Albright Gallery, 1907), 1.

[16] No exhibition catalogue found.

[17] Catalogue of the Exhibition of Paintings by the French Impressionists, exh. cat. (Pittsburgh: Carnegie Institute, 1908), 1.

[18] Exhibition of Paintings by the French Impressionists, exh. cat. (Cincinnati: Cincinnati Museum, 1908), 1.

[19] A Special Exhibition of Selected Paintings by the French Impressionists and of the Works of Six American Artists Residing in Paris, exh. cat. (Minneapolis: Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, 1908), 7, https://reflections.mndigital.org/.

[20] No exhibition catalogue found.

[21] No exhibition catalogue found. Dates from Milwaukee Journal, May 27, 1908, 2.

[22] “In the Field of Art: Western Artists’ Exhibition,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 3, 1904, 30.

[23] Unsigned typed note, box 198, folder 15 1883–1962, bulk 1885–1940, Carnegie Institute, Museum of Art records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, https://www.aaa.si.edu/.

[24] The Academy of Fine Arts of Buffalo was founded in 1862. Some of the cities where the Durand-Ruel collection was shown did not even have their own museums yet; the “twin cities,” St. Paul and Minneapolis, only opened their first permanent museum in 1915 with the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. While some of the institutions existed as libraries or guilds at the time of the traveling exhibition, they later became museums, which more cohesively highlighted their educational goals.

[25] John Beatty to Durand-Ruel & Sons, January 6, 1908, box 46, folder 6, bulk 1885–1940, Carnegie Institute, Museum of Art records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

[26] Paul Durand-Ruel & Sons to J. H. Gest, January 6, 1908, box 45, folder 6, Director’s Records-Incoming Correspondence (CAM/2/1) D50, Cincinnati Art Museum archives, Cincinnati, OH.

[27] Durand-Ruel & Sons to J. H. Gest, January 17, 1908, box 45, folder 6, Director’s Records-Incoming Correspondence (CAM/2/1) D51, Cincinnati Art Museum archives, Cincinnati, OH.

[28] Paintings by the French Impressionists, Buffalo Fine Arts Academy Albright Gallery, 19.

[29] Paintings by the French Impressionists, Carnegie Institute, 5.

[30] Paintings by the French Impressionists, Cincinnati Museum of Art, 9.

[31] “French Art Exhibited,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, March 19, 1908, 5, https://www.newspapers.com/ [login required].

[32] Elizabeth A. Chant, “Unusual Paintings at Public Library,” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, April 26, 1908, 14, http://www.mnhs.org/.

[33] Paintings by the French Impressionists and of the Works of Six American Artists, Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, 5.

[34] Robert Koehler, preface to Paintings by the French Impressionists and of the Works of Six American Artists Residing (Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts), 7–10.

[35] Early French theorists include Louis Edmond Duranty, Théodore Duret, and Jules Antoine Castagnary. In the United States, publications including Henry G. Stephens, “Impressionism: The Nineteenth Century’s Distinctive Contribution to Art,” Brush and Pencil 11, no. 4 (January 1903): 279–99, confined impressionism to select artists, such as Monet, Manet, Renoir. For more on the definition of impressionism, see Richard Shiff, Cézanne and the End of Impressionism. A Study of the Theory, Technique, and Critical Evaluation of Modern Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 14–16.

[36] Catalogue of an Exhibition of Paintings by the French Impressionists, exh. cat., (Cincinnati: Cincinnati Museum, 1907), annotated copy in the Cincinnati Art Museum archives.

[37] For instance, only one piece by Maufra sold during the show’s run at Buffalo’s Albright Art Gallery. In comparison, the same institution’s exhibition of contemporary German painters in 1907 sold a total of eleven paintings. Kurtz attributed the lack of sales to the high prices asked for paintings by Manet, Monet, and Renoir. See Arleen Pancza-Graham, “Charles M. Kurtz (1855–1909): Aspects and Issues of a Cosmopolitan Career” (PhD diss., City University of New York Graduate Center, 2002), 227–28, https://academicworks.cuny.edu/.

[38] Mrs [Marina Griswold] Schuyler Van Rensselaer, “Fine Arts, The French Impressionists, I.,” The Independent, April 22, 1886, 7–8.

[39] Paintings by the French Impressionists, Carnegie Institute of Art, 10.

[40] Chant, “Unusual Paintings at Public Library,” 14.

[41] The same number of pieces were shown at all five stops, and my data counted each time the pieces were shown at a different venue. A piece shown at all five stops was counted five different times, whereas a piece exhibited at only one venue was only counted once.

[42] “French Impressionism at the Albright Gallery,” Academy Notes 3, no. 7 (December 1907): 113–41.

[43] “Showing French Pictures,” Milwaukee Journal, June 3, 1908.

[44] “Notable Collection of 90 Canvases on View at Carnegie Institute,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, February 11, 1908, 2, https://www.newspapers.com/ [login required].

[45] “Gallery and Studio Chat. Exhibitions of Paintings by the French Impressionists at Albright Gallery,” Buffalo Morning Express, October 28, 1907, 5, https://www.newspapers.com/ [login required].

[46] Austin E. Howland, “The Pittsburgh Art Exhibition,” Brush and Pencil 7, no 3 (December 1900): 129–47, describes the French impressionists as having a “worthy place in the exhibition.” See also Zafran, “Monet in America.”

[47] Chant, “Unusual Paintings at Public Library,” 14.

[48] “French Art Exhibited,” 5.

[49] Paintings by the French Impressionists, Cincinnati Art Museum, 5.

[50] Paintings by the French Impressionists, Cincinnati Art Museum, 5.

[51] Paintings by the French Impressionists and of the Works of Six American Artists, Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, 7.

[52] Richard Brettell, “Impressionism and Nationalism: The American Case,” in American Impressionism: A New Vision 1880–1900, eds. Katherine M. Bourguignon and Frances Fowle (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 20.

[53] See references as early as 1883, “Exhibition Art. The Collection to be Seen at the Foreign Exhibition,” Boston Globe, September 16, 1883, 10, “but there is an idea in them and that is revolt against . . . conventionality,” cited in cited in Nancy Mishoe Brennecke, “‘The Painter-in-Chief of Ugliness’: Edouard Manet and Nineteenth-Century America,” (PhD diss., City University of New York Graduate Center, 2001), 152.

[54] “Professor Koehler Gives Talk on ‘Impressionists,’” The Minneapolis Tribune, April 29, 1908, https://www.newspapers.com/ [login required]; “Impressionism No Fad, Says Professor Koehler,” Star Tribune, May 2, 1908, 11, https://www.newspapers.com/ [login required].

[55] Paintings by the French Impressionists, Carnegie Institute of Art, 34.

[56] “Impressionism No Fad, Says Professor Koehler,” 11.