The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Mary Cassatt: Une Impressionniste Américaine à Paris

Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris

March 9–July 23, 2018

Catalogue:

Nancy Mowll Mathews, Flavie Durand-Ruel Mouraux, Pierre Curie,

Mary Cassatt: Une Impressionniste Américaine à Paris.

Paris: Culturespaces/Brussels: Mercator, 2018.

176 pp.; 176 illus.; bibliography; index.

€20.00 (soft cover)

ISBN: 9789462302075

€40.00 (hard cover)

ISBN-10: 9462302081

ISBN-13: 978-9462302082

English edition:

Mary Cassatt: An American Impressionist in Paris.

$45.00

ISBN: 9780300236521

Mary Cassatt: Une Impressionniste Américaine à Paris (Mary Cassatt: An American Impressionist in Paris), an exhibition at the Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris (March 9–July 23, 2018), pays tribute to the artist in the metropolis in which she chose to pursue her career. The American-born Cassatt first settled in Paris in 1874 and later divided her time between the French capital and the nearby countryside, where she died in 1926 at age eighty-two in her château de Beaufresne on the Oise River. Cassatt’s paintings were exhibited first in the official Paris Salon in 1868, followed by the Salons of 1870, 1872, 1873, 1874, 1875, and 1876. Thereafter they were seen in four Impressionist exhibitions (1879, 1880, 1881, 1886), and from the 1890s on, in private galleries. Cassatt, who enthusiastically joined the artists who preferred to be called Independents but became known as Impressionists, gave up showing at the Salon’s official exhibitions (unlike some of her colleagues, Renoir and Monet for example) and was fiercely loyal to the group.

Cassatt’s most extensive exhibition in Paris took place in 1893, when the almost fifty-year old Cassatt had a solo exhibition at Durand-Ruel’s Gallery. As is well known, Cassatt was the only American to join the Impressionist independent exhibitions. Along with the French artist Berthe Morisot, she was a prominent female member of the group. Yet, unlike many of her contemporary artists, both male and female (including Eva Gonzales and Morisot), who were given retrospective exhibitions in Paris after their death, Cassatt never had such an exhibition summing up her oeuvre in the French capital. In 1988, some sixty-two years after her death, the Musée d’Orsay presented a large exhibition of Cassatt’s prints (curated by Martine Mauvieux). Thus the 2018 exhibit at the Musée Jacquemart-André is the first in Paris since the 1893 Durand-Ruel show, to feature a substantial number of Cassatt paintings, pastels, and prints.

The exhibition was guest-curated by Nancy Mowll Mathews, the distinguished Cassatt scholar, in collaboration with Pierre Curie, the chief curator of the Musée Jacquemart-André. The curators succeeded in assembling an impressive group of over fifty works by Cassatt, among them many of the artists’ well-known paintings, pastels, and prints. They secured loans from major American, French, and other European museums. For Mathews this exhibition is yet another step in an illustrious contribution to the study of Mary Cassatt. Among her scholarly work, which is foundational to Cassatt studies, are a biography of the artist, a volume of Cassatt’s correspondence, as well as a monographic study, and a co-authored volume on Cassatt’s prints.[1]

The title of the exhibition, Mary Cassatt: An American Impressionist in Paris, was not chosen by the curators. Although Cassatt was both an American and an Impressionist, she was not “an American impressionist.” The latter refers to American artists of a generation younger than Cassatt, inspired by Impressionist art developed earlier in France. This title was chosen by Culturespaces—the organization that administers (among others) the Musée Jacquemart-André on behalf of the Institut de France, to which Nélie (née Jacquemart), and her husband Edouard André, bequeathed their mansion and extensive art collection. The goal of the title—to attract a large public to the exhibition—was successfully achieved since the exhibit has proven to be highly popular among the French audience and also has attracted a substantial number of American visitors (an estimated 5–10 percent of the total).

The exhibition seeks to treat a broad range of topics in Cassatt’s oeuvre, beyond the usual primary association of her work with the theme of mother and child, which, as Mathews notes in the catalogue, has tended to reduce the fullness of Cassatt’s oeuvre. In addition to presenting the artist as an important interpreter of the “Modern Madonna,” the exhibition shows Cassatt as a member of an American family, an experimenter with new mediums and techniques, a painter of children, and a painter of the modern woman.

Upon entering the first gallery of the exhibition, one encounters Cassatt primarily in relationship to Degas. However, once inside the gallery, turning sideways, one sees a wall with three impressive paintings from Cassatt’s pre-Paris years. She painted these after leaving Philadelphia when she lived, studied, and painted in Italy and other European locations, well before her association with Degas and other Impressionists. Among the paintings, made from the late 1860s through the early 1870s, is Young Woman with Mandolin, which was the first Cassatt painting to be accepted by the Paris Salon, where it was exhibited in 1868. This and the other two paintings, Music (1874) and A Spanish Dancer Wearing a Lace Mantilla (1873), show Cassatt’s considerable abilities as a figure-painter before joining the Impressionists. These works also manifest the steadfast ambition of the artist who, already at age twenty-three, boldly, if light heartedly, declared that she “wanted to paint better than the old masters.”[2]

The two walls that catch our initial gaze as we enter this first gallery effectively present Cassatt primarily in relation to Degas. The left wall features a dramatic juxtaposition of Cassatt’s In the Loge, and Degas’ Portrait of Mary Cassatt, both from ca. 1877–78 (fig. 1). The juxtaposition of these more or less two equal-sized canvases, made in the same years, encourages the viewer to consider them as a duo. Cassatt’s iconic female spectator, paired with Degas’ painting of Cassatt, appears as a juxtaposition of equals. In the Loge represents a young woman dressed in a sober black outfit gazing through her opera glasses at the stage, while in the back, a miniature-size man is energetically pointing his opera glasses at the female spectator.[3] The juxtaposition of this painting with Degas’ portrayal of Cassatt, encourages the interpretation of Cassatt’s painting as a surrogate self-portrait, consequently the dominant female gaze in the picture stands for that of spectator in a theatre or opera. It also represents the gaze of an artist dedicated to making art based on her own perceptions, while being well aware that as a young woman in Paris she is usually herself being looked at. Next to the clarity of Cassatt’s presentation of the woman’s determined gaze, Degas’ portrayal of Cassatt is intriguing in its ambiguity. The enigmatic portrayal represents a woman leaning forward awkwardly. Her gaze does not seem directed at anything in particular. Nor is there a clear purpose to the cards she is holding out, perhaps cartes de visites with photographs.

Cassatt in her later years recognized that the painting has some qualities as art, but thought it represented her as repugnant and did not want anyone to know that she had modeled for it. She thus took the initiative to remove the painting from Paris by urging the dealer Ambroise Vollard to sell it to a collector who resided far away from the French capital. Vollard sold the painting to a Japanese collector, but eventually the painting reached the US (today it is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC). Ironically, this exhibition has brought it back to Paris. Quite in contrast to it, Cassatt’s own small-scale gouache and watercolor Self Portrait (1877–78), which is displayed on the other side of Degas’ painting, shows the well-dressed young artist wearing a Parisian outfit capped by a hat, seated upright, observing herself painting while looking out at us (fig. 2). Compared with Degas’s portrayal, she appears purposeful, actively painting, and exercising her artist’s gaze. The display of the trio on one wall is intriguing, although, due to its smaller scale, the gouache self-portrait remains a bit separate from the two paintings.

Degas’ presence is given further prominence in this gallery. Two Degas prints for which Cassatt modeled in the Louvre, appear alongside a print by Cassatt. These black and white prints were made around 1878 to 1880, during the period in which Cassatt, Degas, and Pissarro worked in close proximity on prints in preparation for Le Jour et le Nuit, a journal or portfolio of prints which never materialized. Degas is further highlighted by featuring Cassatt’s relatively large painting Girl in Blue Armchair (ca. 1877–78) on a wall by itself, next to an extract from a documentary (“Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, the enfants terrible of Impressionism”) presented as a small-scale video projection (fig. 3). The extract explains that Degas painted in the background of this painting. The heading that appears at the top of this wall, “The Birth of a Masterpiece,” together with the brief video segment, suggest some kind of collaboration between Degas and Cassatt on this early Cassatt masterpiece from her Impressionist period.

Altogether the introductory gallery frames Cassatt primarily in relation to the French artist.[4] This relatedness has long both enhanced and diminished Cassatt’s reputation, leading numerous critics and historians to incorrectly label her as Degas’ pupil or disciple, thus implying her lack of originality.[5] Cassatt, who was frustrated by this for many years, wrote to her close friend Louisine Havemeyer, that she hoped the 1915 New York exhibition at the Knoedler Gallery, which featured a substantial number of artworks by her and by Degas (along with some old masters), would prove that she did not copy Degas.[6] This museum-scale exhibit, organized in support of women’s suffrage, by Louisine Havemeyer, who by then was both a preeminent collector and suffrage leader, did contribute to Cassatt’s reputation in the United States. Yet it did not put an end to the lingering false descriptions of Cassatt as “pupil” or “disciple” of Degas.

The next gallery “An American Family: The Models,” presents some of Cassatt’s major portrayals of her family members (fig. 4). Among these are Alexander Cassatt and his Son Robert Kelso (1884–85), a portrait of her brother and his son; his wife, Mrs. Alexander J. Cassatt in a Blue Evening Robe Seated before a Tapestry Frame (1888), and The Cup of Tea (1880–81), which features her sister Lydia seated, clad in an elegant Parisian pink outfit (fig. 5). Cassatt’s family members, whether they lived with the artist in Paris (like her sister and parents) or came for visits from the US, served as her models on many occasions. Some of these paintings were primarily portraits, yet many also represented everyday moments in a comfortable bourgeois lifestyle. A good example of the latter is The Cup of Tea, which was singled out for praise by Joris Huysmans when it was shown at the Impressionist exhibit in Paris.

“Experimentations: The Creative Process of Cassatt,” the topic of the following gallery, which is dedicated to prints, features five color prints from 1890–91 chosen from a series of ten color prints, along with two black and white ones (fig. 6). Cassatt’s series of color prints was inspired by Japanese prints. They have been praised by many as among Cassatt’s best works, admired for their exquisite lines and compositions, subtle coloration, and tendency towards abstraction and stylization. One only regrets that all ten of them, conceived as a series, could not be shown here.

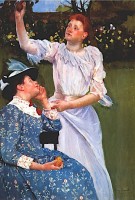

The next gallery, “A Modern Woman,” highlights Cassatt’s monumental-scale mural, commissioned for the Woman’s Building at the Chicago World Fair’s of 1893, (fig. 7). The Woman’s Building was an ambitious international project that featured exhibitions of women’s arts, crafts, literature, and a wide variety of cultural achievements from around the world. Although the small black and white photograph displayed in the gallery can hardly represent the lost mural which was almost 59 feet wide and close to 13 feet high at the center, this gallery manages to give a good a sense of it by displaying the painting Young Women Picking Fruit (1892; fig. 8). The painting was made close to the time Cassatt painted the mural and shows the style, bright color, and symbolism that characterized the mural. Its theme is also related to the central part of that mural, which was titled “Plucking the Fruits of Knowledge and Science.” The mural modernized the story of the Garden of Eden and gave it a feminist interpretation, in which women’s picking the fruit of knowledge is wholly positive and is an endeavor of women and girls with no Adam or snake in the vicinity. It featured women in contemporary fashions in an orchard, picking fruit and handing it to the next generation. The two color prints in this gallery are related to the theme of the mural as well. Had space not been an issue, one could have gotten a more extensive impression of the context for the mural by including some of the books, catalogues, and photographs featuring the Woman’s Building and the mural.

This gallery does not feature the theme of the modern woman through the mural alone, but includes also the typical Impressionist themes of leisure out of doors. It presents a painting, two watercolors, and a color print, none of which have an allegorical meaning. A large oil painting and a print depict scenes of women and children in a boat, looking at, or feeding ducks (fig. 9). Two watercolors from ca. 1910 appear to be studies and tend to a more abstract rendering, leaving substantial portions of the white paper exposed, whereas the painting and print are fully defined and color saturated. The exhibition thus suggests Cassatt’s dual approach to the theme of modern woman. On the one hand Cassatt’s modern woman is related to feminist ideals of the 1890s as reflected in the Woman’s Building at the Chicago World’s Fair, stressing women’s achievements and contribution to humanity. On the other, Cassatt’s modern women are enjoying an upper-class bourgeois leisure in nature, a world that appears quite apart from any political concerns.

After viewing this gallery, the visitor has to turn back in order to see the rest of the exhibition, which continues in a small gallery of a documentary nature, featuring text and enlarged photographs. It presents Cassatt as playing an important role in the diffusion of Impressionism along with the gallery dealer of the Impressionists and the chief dealer representing Cassatt—Durand-Ruel. A blown-up photograph covering an entire wall shows Cassatt on the steps in front of her château visited by Mme. Joseph Durand-Ruel, giving one a sense of the social life of the artist.

An excellent selection of Cassatt’s portraits of children is presented in the next gallery. It shows the artist’s variety of approaches to the theme. Her outstanding pastel, A Baby in Blue in his Baby Carriage (1880–81), tends towards the abstract, highlighting very free pastel strokes surrounding the baby’s face. Another pastel, Portrait of Marie-Therese Gaillard (1894) is a highly accomplished portrayal depicting the thoughtful expression of the girl whose head is placed within a structured abstracted composition. Portrait of Mademoiselle Anne-Marie Durand-Ruel (1908) as well as Portrait de Mademoiselle Louise-Aurore Villeboeuf (1901) are pastels that show signs of being commissioned portraits yet are nonetheless a tour de force. Each represents a different girl in elegant attire including a large fashionable hat and perfect coiffure, seated in an armchair, yet the artist succeeds to express each child’s individuated expression. The pastels in this gallery were made over a period of four decades, showing the artist’s mastery in the medium as well as exceptional ability to render the personalities of the children.

The exhibition culminates with the final gallery dedicated to the topic of “The Modern Madonnas,” which interprets Cassatt’s mother and child theme as modernizing the representation of maternity (fig. 10). It includes seven paintings and pastels and two prints on the theme of mother and child, most made during the 1880s and 1890s, with one rarely seen very late painting from 1914 that appears quite different from the rest. One of Cassatt’s masterpieces on this theme, Mother and Child (the Oval Mirror) (1899), which was in the Havemeyer collection, is perhaps the best example of Mathews’ interpretation of Cassatt’s secularizing the Madonna and child theme while suggesting a sense of a modern sacred family (fig. 11). Degas’ often quoted comment captures the idea, “It is the small Jesus with his English governess” (82). It should be noted, however, that the sumptuously clad woman in a loose silk peignoir in pastel colors next to the standing nude boy embracing her, represents a well-to-do mother in the luxury of her private home, rather than a hired nanny at work.

Installed in the relatively small galleries on the upper floor of the museum, the exhibition is necessarily compact. These galleries are entirely different in character from the sumptuous spaces on the ground floor of the Jacquemart-André mansion, which display the permanent collection of European old masters. The smaller galleries on the upper floor had initially functioned as storage space for the mansion’s owners and later on became the museum director’s apartment. Only recently were they converted into air-conditioned exhibition spaces, allowing the museum to hold temporary specialized exhibitions while displaying the permanent collection downstairs.

Larger galleries would have offered a more spacious habitat for this superb selection of paintings, pastels, and prints, yet this space offers a rare intimate experience when it comes to viewing Impressionist art works. The modest gallery spaces are more akin to the scale of an apartment than to mansion halls or galleries of a large museum. The advantage is that visiting the Cassatt exhibition in these galleries one is always in close proximity of the artworks. This contrasts with most Impressionist exhibitions, which tend to be blockbusters in major museums and display the works in sizable galleries accommodating a very large number of visitors. The limited space for this exhibition, however, also presents some limitations with which the curators and exhibition designer had to contend. It did not allow for English wall texts and must have led to the unusual decision to use even a small cramped area within a space designated for the toilets, placing two stands in front of which visitors could sit down to view exemplars of the exhibition catalogue.

The beautifully illustrated and informative exhibition catalogue presents a surprising emphasis on Nélie Jacquemart. The second image in the catalogue is a full-page reproduction of a photograph of a mother and child attributed to the mansion owner from the days she was a portrait artist. Discovered (along with a trove of additional photographs) by Curie, the curator of the museum, this photograph features a well-attired Parisian mother of the late nineteenth century with an almost naked child casually sitting on her lap. Jacquemart used this kind of photograph for painting her portraits. She thus supervised photo sessions at a local photographer’s studio in order to obtain images that suited her goals for her painted portraits.[7] The connection to the theme of mother and child that is so closely identified with Cassatt’s oeuvre, as well as the wish to highlight the venue, likely motivated the prominent presence of this image in the catalogue, yet the full page photograph overstates Jacquemart’s significance in this context.

There is some historical irony in the choice of this venue—the nineteenth-century private mansion of Nélie Jacquemart and her husband Edouard André—for this exhibition. He, from a banking family and she, a former painter, the couple were contemporaries of Cassatt, and the construction of their mansion was completed about a year after Cassatt settled in Paris. The couple was dedicated to collecting old master paintings and succeeded in forming an impressive collection that filled their mansion. Like them, Cassatt had a deep appreciation for old masters and an interest in collecting them, by advising American collectors, chiefly, Henry Osborne Havemeyer and his wife, Louisine Elder Havemeyer on collecting European masterpieces (along with Gustave Courbet, Edouard Manet, and the Impressionists). But unlike the Jacquemart-Andrés, Cassatt also had an avid interest in promoting the collection of contemporary avant-garde French painting. And she was dedicated to do all she could so that as many great masterpieces, old and new, would reach America. Nélie Jacquemart, who gave up her own painting when she became Mrs. André, dedicating herself to collecting instead of making art, had no interest in the art of painters of her own time, Cassatt included. Thus, using her mansion as the site for this belated homage to Cassatt in Paris, is an ironic twist. On the other hand, it may also be a fitting venue, for one, because Cassatt believed so strongly in seeing the avant-garde art of her time in the longer historical context of the old masters, and in proximity to them.

Ruth E. Iskin

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

Beer-Sheva, Israel

ruth.e.iskin[at]gmail.com

[1] Nancy Mowll Mathews, ed., Cassatt and Her Circle, Selected Letters (New York; Abbeville Press, 1984); Mathews, Mary Cassatt (New York: Abrams in association with the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1987); Mathews and Barbara Stern Shapiro, Mary Cassatt: The Color Prints (New York: Abrams in association with Williams College Museum of Art, 1989); Mathews, Mary Cassatt: A Life (New York: Villard Books, 1994).

[2] Letter by Eliza Haldeman to Mrs. Samuel Haldeman, May 15, 1867, in Nany Mowll Mathews, ed., Selected Letters, 46.

[3] The painting has elicited a lot of commentary. See, for example, Griselda Pollock, Mary Cassatt: Painter of Modern Women (London: Thames and Hudson, 1998).

[4] Mathews initially curated an exhibition of Degas and Cassatt in 1981 at the San Jose Museum of Art, in which she viewed the relatedness of the art of Degas and Cassatt as a mutual dialogue rather than merely an influence of the former on the latter. A larger exhibition, Degas Cassatt, curated by Kimberly A. Jones, at The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, in 2014, elaborately explored the Degas-Cassatt artistic dialogue.

[5] For an analysis of the problematic discourse of Cassatt as Degas’ disciple, and more broadly issues of gender and art history as they relate to the discourse on Degas and Cassatt, see Ruth E. Iskin, “The Collecting Practices of Degas and Cassatt: Gender and the Construction of Value in Art History” in Perspectives on Degas, ed. Kathryn Brown (London: Routledge, 2017), 205–30.

[6] Cassatt, letter to Louisine Havemeyer, in Mathews, Selected Letters, March 12 [1915], 322. For revised figures and identifications of the works by Cassatt in the 1915 exhibition, see Iskin, “The Degas and Cassatt 1915 Exhibition in Support of Women’s Suffrage,” in Monographic Exhibitions and the History of Art, eds. Maia Gahtan and Donatella Pegazzano (London: Routledge, 2018), 26–37.

[7] My thanks to Pierre Curie for sharing this information with me.