The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

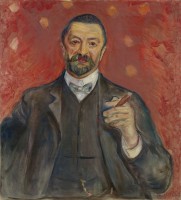

Though not a “new discovery” in the strictest sense, the portrait by Edvard Munch depicting the German physicist Felix Auerbach has not been seen in public for nearly forty years and was therefore one of the lesser-known works by the artist (fig. 1).[1] The portrait was first published in March 1964 in a short article in The Burlington Magazine.[2] The author, Ruth Kisch-Arndt, a niece of Auerbach and then owner of the painting, described the genesis of the portrait and its journey from Jena, Germany, to New York City. More than half a century later, this painting recently entered the collection of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam—representing a significant addition to the museum’s expanding collection of works by Vincent Van Gogh’s contemporaries.

Edvard Munch painted this portrait of the German collector and scholar Felix Auerbach in 1906, at a time when Van Gogh was very much on his mind. By then works by Van Gogh were widely exhibited and collected in Germany. The art dealer Paul Cassirer, for example, had organized an exhibition in Berlin in December 1904 with eleven of Van Gogh’s paintings, including several portraits. Around the same time, he displayed many works by Munch in his gallery. The artistic affinities between Van Gogh and Munch were recognized since the 1890s and the two artists were often mentioned in the same breath. The parallels between them were the central focus of the exhibition Munch: Van Gogh at the Van Gogh Museum (September 25, 2015–January 17, 2016), organized in collaboration with the Munch Museum in Oslo.

Munch clearly knew of Van Gogh’s work as early as 1889, when he was in Paris on a two-year study grant; specific effects found in Van Gogh’s art started to appear in his work the following year.[3] The two probably never met, but ever since the 1890s Van Gogh has been regarded as a major stylistic and conceptual source for Munch.[4] The artists shared a profound interest in the human figure. When Van Gogh was in Arles in 1888, he devoted himself to painting modern portraits, and color was essential to his process of modernization.[5] He believed in the expressive and decorative potential of colors and searched for alternatives to descriptive, local colors. Munch’s portraits follow the path set by Van Gogh, as is especially clear from his series of portraits from the 1900s. The portrait of Felix Auerbach is part of a group of portraits of intellectuals, collectors, and critics that he produced in the first decade of the twentieth century that also included portraits of Harry Graf Kessler, Curt Glaser, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Max Linde.

The Auerbach Portrait

It was on the occasion of a visit to the Friedrich Nietzsche Archive in Weimar at the end of 1905 that Felix Auerbach (1856–1933) and his wife Anna (née Silbergleit; 1861–1933) first became acquainted with the work of Munch. The couple was immediately impressed by Munch’s portrait of Nietzsche that they saw there, and shortly after they invited the artist to visit them in Jena to paint a portrait of Felix.

A childless Jewish couple, the Auerbachs belonged to the highly cultivated intellectual milieu of Jena, a university town in Thuringia, Germany. Auerbach was a physicist from Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland). In 1889 he was appointed associate professor of theoretical physics at the University of Jena. Owing to objections to his Jewish descent, it was not until 1923 that Auerbach was advanced to full professor, a position he should have been granted many years earlier given his stature as a scientist. Anna Auerbach was politically active as an advocate of women’s rights for Jena’s branch of the International Women’s League for Peace and Freedom.[6]

Felix and Anna took a great interest in music, literature, and the visual arts. Felix was particularly fond of music, and the investigation of acoustics and music even played a role in his scientific research. His inaugural lecture at Breslau, entitled “Harmonie und Melodie vom wissenschaftlichen Standpunkte betrachtet” (Harmony and Melody Considered from a Scientific Standpoint), bears testimony to his profound involvement with music.[7] Visual art, too, was an important part of the Auerbach household. Both Felix and Anna were founding members of the Jenaer Kunstverein (Jena Art Club), a progressive and outward-looking art society established in 1903.[8] The society provided a platform for the most avant-garde artists of the time, including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee—to name but a few.[9] The Auerbachs’ involvement in this society is telling of their enthusiasm and support of contemporary art. It was most likely through their close connection with the art society that the couple made the personal acquaintance of artists like Kandinsky and Klee. Their interest in modernism also extended to the field of architecture. In 1924, they commissioned Walter Gropius, director of the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar, to design a new home. Theirs was one of only a few private residences designed by Gropius (fig. 2).[10]

Even before the Auerbachs moved into their new Bauhaus-style house in the fall of 1924, their home had been an important cultural center of Jena for more than two decades.[11] Over the years, they had welcomed countless intellectuals, academics, artists, writers, musicians, and architects. Their many friends included the writer and art patron Harry Graf Kessler, Nietzsche’s sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, the architect Henry van de Velde, the poet and writer Richard Dehmel, and the composer Max Reger. The couple frequently hosted musical soirées at their house. Felix, himself an accomplished amateur musician, livened up such evenings with performances of his own.[12] It was in the music room—the center of gravity of the Auerbach household—that Munch’s portrait of Felix found its place on the wall and witnessed the countless get-togethers that took place there.[13]

Painting Felix Auerbach

After their introduction to the art of Munch, the couple made an endeavor to get in touch with the artist to commission a portrait of their own. It is possible that the contact between Munch and the Auerbachs was facilitated by the archaeologist and art historian Botho Graef, who had settled in Jena in 1904.[14] He had made the acquaintance of Munch in Berlin, and a short note dating from December 21, 1905, shows that he passed on a letter from Munch to the Auerbachs.[15] Munch initially expressed his doubts about accepting the commission to paint Felix, as he feared for his mental health. This becomes clear in a letter from Anna Auerbach to Munch in which she kindly reassures him that the great temperament expressed in his paintings was exactly what she and her husband admired, and that they did not expect its creator to possess a conventional personality (Persönlichkeit).[16] Apparently, this put Munch’s mind at rest, as he made the journey to Jena in early February 1906. Munch would go on to receive a sum of 500 marks for the commission.[17] Although Munch spent several days at the Auerbach residence to paint his portrait of Felix, the image was laid down fluently and confidently in a single session.[18]

Characteristic of Munch’s portraits from this period, and hence also that of Auerbach, is the way Munch conveyed the vitality of modern life. He has rendered Auerbach as an assertive man of the world. The painting is a frontal portrait of Felix, smartly dressed in a three-piece suit and bow tie. His watch chain and cigar are further signs of his sophistication. The most outstanding feature of the portrait is the bright red background interspersed with coarse blotches of yellow. Using these strong colors, Munch modeled an undefined, yet decorative and highly expressive background that gives the portrait a monumental appearance. In so doing, Munch was following a tradition that had originated in the late nineteenth century and that can also be found in the oeuvre of Van Gogh—namely in his 1888 portraits from Arles like the one of Madame Ginoux, the so-called L’Arlésienne (1888; Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Furthermore, the abrupt cropping and the sparse filling of the background are also typical of this period.

It seems that Munch initially refrained from signing the portrait, as Felix Auerbach had asked of him in a short cryptic poem written in April 1906.[19] The surviving correspondence indicates that Munch had the desire to make some changes to the hand of the figure, but this never happened.[20] In an undated letter, Munch claims that he was afraid of ruining the painting: “Unfortunately, I was unable to make any changes to the portrait of Professor Auerbach—I was afraid I might ruin the painting—and the painting is very good.”[21] Anna Auerbach later confessed that she was relieved that Munch had refrained from making any changes as “it would have been such a shame if [the painting] had forfeited any of its assurance and passion.”[22]

The Auerbachs’ Fondness of the Portrait and Its Creator

The Auerbachs were delighted with the painting and cherished it throughout their lives, as is evident from their surviving letters to Munch. For example, on July 1, 1908, Anna wrote, “I am so pleased to tell you again how much I love every stroke and every dot of your portrait of my dear husband, and how much it pleases me to own it, every day afresh.”[23] Their appreciation of Munch and the portrait is emphasized further by the fact that they agreed to lend the portrait to several exhibitions. By allowing their beloved painting to leave their home on several occasions, the couple helped shape Munch’s artistic reputation. It was first exhibited barely a month after its completion, when it was featured alongside three Munch landscapes in an exhibition at the Jenaer Kunstverein (March 7–18, 1906).[24]

As is clear from the letter quoted above, Munch himself was pleased with the portrait. Consequently, he asked to borrow it from the Auerbachs on several occasions. For example, in the winter of 1907 it was included in a major exhibition at the Kunstsalon Cassirer in Berlin (fig. 3), where it was presented alongside his portraits of Nietzsche and Harry Graf Kessler as illustrative of the group of portraits he painted during his stay in Thuringia in 1906.[25] Munch also selected the painting for the landmark Sonderbund exhibition of 1912 in Cologne, which was an extremely important retrospective for the artist (fig. 4). Like Van Gogh, he was allocated his own gallery in the center of the exhibition (room 20), in which he exhibited thirty-one paintings (nos. 522–53), including ten portraits. In a letter to Jappe Nilson, Munch wrote: “The main section is Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Cézanne. Three rooms of Van Gogh! Eighty-six pictures, of the greatest interest. I am almost ashamed to have been honored so highly—but, it was their opinion. Hopefully, they don’t regret it.”[26]

There is no indication that the Auerbachs and Munch ever met again in person, but they maintained friendly relations by correspondence for many years. Munch expressed his appreciation of the couple in an undated letter to the art collector Albert Kollmann, in which he also wrote that he regretted never having painted Anna Auerbach.[27] Anna occasionally sent Munch letters in which she continued to express the desire to see him again. She also had hopes that he would again exhibit in Jena in the autumn of 1912; however, her dream went unrealized.[28] In early 1908, Anna suggested that Munch come to Jena so that they could listen to music in the music salon where his “wonderful duo” heightened the beauty of the rhythm and sound of the music performed there.[29] There is no indication as to what this second artwork of the “duo” might have been, and in all probability the couple did not own another painting. Nonetheless, the fact that Munch’s portrait of Felix was displayed in the music room for their many guests to see reflects their appreciation of the artist.

The Auerbachs eventually augmented their collection with the acquisition of some graphic works by Munch. In 1911, Anna wrote to the artist about their trouble in finding examples with art dealers; they did not seem to be available anywhere.[30] Eventually, however, the Auerbachs managed to acquire a couple of Munch prints in October 1911, one being a version of Kristiania-Bohème II.[31]

From New York to Amsterdam

Felix and Anna Auerbach took their own lives in late February 1933. According to a letter from Anna addressed to her niece, they passed away with peace of mind. They had decided it was their time, as the seventy-seven-year-old Felix was suffering from the consequences of a recent stroke.[32] However, the fact that Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany several weeks earlier on January 30, 1933, can hardly be overlooked, as German-Jewish suicides were a common response to Nazi racial policy during this period. In the months after the Nazis came to power, storm troopers frequently and arbitrarily attacked Jews, and many committed suicide out of fear of violence.[33] Whether this had any connection to the Auerbachs’ joint suicide cannot be verified, but Bruno Kisch—the husband of Ruth Kisch-Arndt, who inherited Munch’s painting after their deaths—had no doubt that this was indeed the case.[34]

In 1938, during the build-up to the outbreak of the Second World War, Ruth Kisch-Arndt and her husband took refuge in the United States, and fortunately they were able to take Munch’s portrait of Felix Auerbach with them. Between 1971 and 1980, the Auerbach portrait was on long-term loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.[35] It was auctioned in 1980 and remained in private collections until its acquisition by the Van Gogh Museum in the summer of 2017.

Now that this iconic portrait has found its way to the Van Gogh Museum, it is finally possible to permanently visualize the artistic connections between Munch and Van Gogh. The expressive, colorful and decorative portrait of Auerbach is a beautiful and strong example of this affinity. Together with the paintings by Van Gogh in the museum’s collection, it will show how both Munch and Van Gogh sought to modernize art, and how they each developed an expressive visual language to understand and express the universal emotions of human existence (figs. 5, 6).

During his short life, Van Gogh did not allow his flame to go out. Fire and embers were his brushes. I have thought and wished that I would not let my flame go out, and with a burning brush to paint until the end.

—Edvard Munch, October 28, 1933.[36]

Lisa Smit

Associate Curator

Van Gogh Museum

Maite van Dijk

Senior Curator

Van Gogh Museum

Das Haus Auerbach was published by Martin S. Fischer and Barbara Happe in 2003. It has proved an important source of information on Munch’s portrait of Felix Auerbach—and we are grateful for their insights. In addition, we would like to express our gratitude to various colleagues for sharing their knowledge and expertise, which greatly contributed to our research: Magne Bruteig, former senior curator of prints and drawings, Munch Museum, Oslo; Petra Pettersen, curator of Munch paintings, Munch Museum, Oslo; Lasse Jacobsen, research librarian, Munch Museum, Oslo; Michael Simonson, archivist, Leo Baeck Institute Archives, New York; Hadassah Assouline and Tami Siesel, Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, Jerusalem; René Boitelle, senior conservator, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; Marije Vellekoop, head of collections and research, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; Alison Hokanson, assistant curator of European paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and Kate Bell, editor.

[1] Gerd Woll, Edvard Munch: Complete Paintings. Catalogue Raisonné 2 (London: Thames & Hudson, 2009), 689, catalog no. 686. The provenance of the work reads: Felix Auerbach, 1906–33; Ruth Kisch-Arndt (niece of Felix Auerbach), subsequently inherited by her family, 1933–80; Private collection, 1980–2008; Private collection, 2008–17. The exhibition history includes Portrait von Hr. Professor Auerbach, Kunstverein, Jena, 1906; Bildnis: Professor A., no. 78, Cassirer, Berlin, 1907; Professor F. Auerbach, Jena, no. 537, Sonderbund, Cologne, 1912; long-term loan, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1971–80.

[2] Ruth Kisch-Arndt, “A Portrait of Felix Auerbach by Munch,” The Burlington Magazine 106 (March 1964): 131–33.

[3] Munch may have seen the Salon des Indépendants of 1889, where Van Gogh was represented with the paintings Starry Night and Irises. He must have visited the Salon des Indépendants of 1890, where Van Gogh was again represented, this time with ten paintings. See Maite van Dijk, Magne Bruteig, and Leo Jansen, Munch : Van Gogh, exh. cat. (Amsterdam; Oslo: Van Gogh Museum; Munch Museum, 2015), 122.

[4] Thadée Natanson was the first to identify Van Gogh as a source of inspiration for Munch in La Revue blanche 12 (1897): 458.

[5] Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Arles, August 15, 1888, letter no. 662, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, http://vangoghletters.org/vg/.

[6] Martin S. Fischer and Barbara Happe, Das Haus Auerbach: Von Walter Gropius mit Adolf Meyer (Tübingen, Germany: Wasmuth, 2003), 60. Felix’s own affiliation to this organization attests to his support of his wife in these activities.

[7] Fischer and Happe, Das Haus Auerbach, 62–64. Other publications by Auerbach about music include “Das absolute Tonbewusstsein und die Musik,” Sammelbände der Internationalen Musikgesellschaft 8 (1906/07) and Die Grundlagen der Musik (Leipzig, Germany: J. A. Barth, 1911).

[8] Rausch und Ernüchterung: Die Bildersammlung des Jenaer Kunstvereins—Schicksal einer Sammlung der Avantgarde im 20. Jahrhundert (Jena, Germany: Bussert & Stadeler, 2008), 7.

[9] See Rausch und Ernüchterung.

[10] Fischer and Happe, Das Haus Auerbach, 12. The house still exists in all its original glory.

[11] Fischer and Happe, Das Haus Auerbach, 39.

[12] Volker Wahl, “Felix und Anna Auerbach: ‘Kunstmäzene’ in Jena,” in Deutsch-jüdisches Kulturerbe im 20. Jahrhundert: Lebensleistungen, Schicksale, Humanistisches Vermächtnis, ed. M. Schmid and U. Zwiene (Jena, Germany: Städtische Museen, 1992), 40.

[13] Fischer and Happe, Das Haus Auerbach, 53. In the house designed by Gropius, Munch’s portrait again featured prominently, as is indicated by a postcard from the Auerbachs addressed to Edvard Munch of December 26, 1927 (see fig. 2), letter no. MM K 2050, Munch Museum, Oslo, accessed on November 20, 2018, https://www.emunch.no/.

[14] How the Auerbachs and Munch met cannot be indisputably proved. According to Ruth Kisch-Arndt, one of the Auerbachs’ illustrious friends (Meier-Graefe, Van de Velde, or Dehmel) must have introduced them to Munch. Ruth Kisch-Arndt, “A Portrait of Felix Auerbach by Munch,” The Burlington Magazine 106 (March 1964): 131. According to Volker Wahl, the Auerbachs and Munch met in person at the Nietzsche Archive on December 7, 1905. Volker Wahl, Jena als Kunststadt. Begegnungen mit der modernen Kunst in der thüringischen Universitätsstadt zwischen 1900 und 1933 (Leipzig, Germany: Seemann, 1988), 95–96. We have found no substantial proof for either premise.

[15] Letter from Franz Botho Graef to Edvard Munch, December 21, 1905, letter no. MM K 2405, Munch Museum, Oslo, accessed on November 20, 2018, https://www.emunch.no/.

[16] Letter from Anna Auerbach to Edvard Munch, December 18, 1905, letter no. MM K 2040, Munch Museum, Oslo, accessed on November 20, 2018, https://www.emunch.no/.

[17] This is comparable to $3,600 in 2018.

[18] According to René Boitelle, senior conservator at the Van Gogh Museum.

[19] “Wann kommen Sie? / Der Hypnotiseur. / Wann kommen Sie? / Das zu signierende Porträt /.” Letter from Felix Auerbach to Edvard Munch, April 24, 1906, letter no. MM K 2041, Munch Museum, Oslo, accessed on November 20, 2018, https://www.emunch.no/. It is likely that the portrait was eventually signed in early 1907, when it was sent to Berlin to feature in an exhibition at the Cassirer gallery.

[20] This was confirmed by René Boitelle, senior conservator at the Van Gogh Museum.

[21] “Es war mir leider nicht möglich das Portrait Professor Auerbach zu verändern—Ich fürchtete dass ich das Bild verderben konnte—und das Bild ist sehr gut.” Letter from Edvard Munch to Anna Auerbach, n.d., letter no. MM N 2770, Munch Museum, Oslo, accessed on November 20, 2018, https://www.emunch.no/.

[22] “Ja, ich danke Ihnen noch ganz besonders, dass Sie nicht versucht haben, irgend etwas daran zu ändern. Es hätte können etwas von der Sicherheit und Leidenschaftlichkeit einbüssen . . . und das wäre zu schade gewesen.” Letter from Anna Auerbach to Edvard Munch, July 1, 1908, letter no. MM K 2044, Munch Museum, Oslo, accessed on November 20, 2018, https://www.emunch.no/.

[23] “Ganz besonders freut es mich, Ihnen wieder einmal sagen zu dürfen, wie ich jeden Strich und jeden Punkt an Ihrem Bildniss meines Mannes liebe und wie ich mich über diesen Besitz an jedem neuen Tage von neuem freue.” Letter from Anna Auerbach to Edvard Munch, July 1, 1908, letter no. MM K 2044, Munch Museum, Oslo, accessed on November 20, 2018, https://www.emunch.no/.

[24] Wahl, Jena als Kunststadt, 97.

[25] Wahl, Jena als Kunststadt, 98.

[26] “Die Hauptabteilung wird van Gogh, Gauguin und Cézanne—3 Säle voll van Gogh! 86 in höchstem Maß interessante Bilder—lch schäme mich fast daß ich so viel Platz bekommen habe—aber wenn das nun so gedacht war—Hoffentlich bereut man es nicht.” Letter from Edvard Munch to Jappe Nilsen, May 23, 1912, letter no. Ms. fol. 3578, PN 752, Munch Museum, Oslo, accessed on November 20, 2018, https://www.emunch.no/.

[27] Letter from Edvard Munch to Albert Kollmann, n.d., letter no. MM N 2296, Munch Museum, Oslo, accessed on November 20, 2018, https://www.emunch.no/. The letter is undated, but it is most likely a response to a letter from Kollmann to Munch dated March 2, 1912.

[28] Letter from Albert Kollmann to Edvard Munch, March 2, 1912, letter no. MM K 2684, Munch Museum, Oslo, accessed on November 20, 2018, https://www.emunch.no/.

[29] Letter from Anna Auerbach to Edvard Munch, February 22, 1908, letter no. MM K 2043, Munch Museum, Oslo, accessed on November 20, 2018, https://www.emunch.no/.

[30] Letter from Anna Auerbach to Edvard Munch, July 13, 1911, letter no. MM K 2046, Munch Museum, Oslo, accessed on November 20, 2018, https://www.emunch.no/.

[31] Letter from Anna Auerbach to Edvard Munch, October 28, 1911, letter no. MM K 2048, Munch Museum, Oslo, accessed on November 20, 2018, https://www.emunch.no/.

[32] Farewell letter from Anna Auerbach to her niece Elsa, February 25, 1933, Felix Auerbach collection, inventory no. AR 3958, Leo Baeck Institute, New York.

[33] Christian Goeschel, Suicide in Nazi Germany (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 96–97.

[34] Bruno Kisch, Wanderungen und Wandlungen: Die Geschichte eines Arztes im 20. Jahrhundert (Cologne: Greven Verlag, 1966), 261.

[35] And not, as is wrongly listed in the catalogue raisonné, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York City. See Woll, Edvard Munch, 689.

[36] “van Gogh lod i sit korte løb sin flamme ikke slukke—Ild og glød var i hans pensel de få . . . år han brændte sig op for sin kunst— . . . Jeg havde tænkt og villet i mit længere løb og med flere penger til min raadighed som han ikke la min flamme slukne . . . og ikke og med brændende pensel ma male til det sidste.” Note from one of Munch’s sketchbooks, October 28, 1933, letter no. MM T 2748, Munch Museum, Oslo, accessed on November 20, 2018, https://www.emunch.no/.