The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Introduction

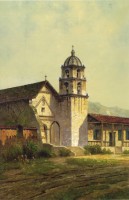

In 2014, the Santa Barbara Mission Archive-Library launched a fundraising campaign to conserve a series of paintings of the California missions by the prolific British-US artist Edwin Deakin (1838–1923). The paintings, one for each of the twenty-one Franciscan missions established by Spanish authorities in Alta California from 1769 to 1823, were privately donated to Mission Santa Barbara (fig. 1) in the 1950s. Like the buildings they represent, the works had fallen into disrepair in the years since their creation. Pushing for the conservation effort, the Santa Barbara Mission Archive-Library argued that the paintings are “important historical artifacts” that testify to California’s cultural heritage.[1] The hope the paintings would serve as visual and material evidence of California’s history was central to Deakin’s project from the start; indeed, contemporary critics proclaimed him the foremost “artist-historian” of his day.[2] A closer look at his work raises the complicated question of how history might be visually produced. In what way are Deakin’s paintings historical artifacts? What history are they artifacts of?

Completed between 1897 and 1899—more than six decades after the missions were mostly abandoned in the years following the 1833 Mexican Act of Secularization—Deakin’s paintings are not artifacts of the mission period itself. In fact, the project originated as its own preservation effort of sorts. At the turn of the twentieth century, the neglected missions were perceived to be in dire need of rescue and recuperation; Deakin’s endeavor was a deliberate attempt to raise awareness for the cause. Furthermore, the Santa Barbara series was produced with preservation in mind in a more literal sense: these small works are copies of twenty-one larger mission paintings, now in the collection of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. The duplicates were intended as backup in case of damage to the originals: Deakin lost much of his early work in the 1871 Great Chicago Fire and must therefore have been especially alert to the need for historical preservation. A third set of the mission paintings, in watercolor, is currently in the collection of the Santa Barbara Historical Museum. Finally, as if sixty-three paintings were insufficient to win attention to the efforts made to save the missions, the artist also reproduced the images in his short book The Twenty-One Missions of California, published in multiple editions starting in 1899.[3]

Deakin was far from the only artist to tackle this subject. Like many of his colleagues, his works integrate the mission buildings into their landscapes, creating a sense of harmony between man and nature. Deakin’s work is distinctive, however, in its rather strange approach to time. Presenting neither a romanticized past nor a specific present, the artist divorces the missions from history, even as he asks his viewers to celebrate and preserve it. In this, he was successful: Deakin exhibited the series to great fanfare at San Francisco’s Palace Hotel in 1900. Critics testified to the works’ authenticity, praising the artist’s picturesque approach and commitment to truth.[4] Surely, they wrote, Deakin’s own pilgrimages to each mission site would inspire others to follow in his wake. Reviews agitated not only for the preservation of the missions but for the purchase of the paintings themselves by the state of California on the basis of the important historical work they performed in documenting the feared-to-be-disappearing missions for posterity. One writer for Brush and Pencil suggests the conflation of representation and represented that has often characterized the project’s reception: “Being of the old California that is fast succumbing to time and change,” he wrote of the paintings, “they should be for the California of today.”[5]

We might fruitfully approach Deakin’s project from various art-historical angles. The paintings clearly belong to the diverse body of art and architecture associated with the missions. They also offer strong evidence that visual culture helped drive the widespread Spanish Revival of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century California. Landscape historian Elizabeth Kryder-Reid’s important recent examination of the lived spaces and physical landscapes of the missions has shown that these are significant but understudied fields.[6] Deakin’s work also participates in the long tradition of landscape painting in the western United States and can be seen in relation to the transnational adaptation of landscape aesthetics more generally.[7] And yet, while they have often acted as illustrations, Deakin’s mission paintings have rarely been examined from a critical art-historical perspective.[8] Perhaps this oversight is due to the perception—now as then—that the function of the series is primarily historical in nature. The paintings’ lack of stylistic originality or even contemporaneity for their time supports this explanation, as does their current display in history and natural history museums.

This article contends, however, that the understanding that Deakin’s paintings do valuable historical work is directly tied to visual concerns. The artist inarguably does produce a specific narrative of California’s history, a narrative linked to the physical transformation of the natural landscape effected by successive waves of colonization: the Spanish establishment of the missions on Native American land, the conversion of mission land into the rancho system in the years California was under Mexican rule, and the disintegration of the same after US expansion into the West in the Gold Rush years. I argue that these transformations are paralleled by Deakin’s own intensive and deliberate efforts to visually transform the land through the language of the picturesque. By bringing together diverse geographies and contested histories into a single aesthetic framework, Deakin envisions the landscape as a consistent and coherent image subject to the viewer’s gaze. That the paintings were then remade, reproduced, and redeployed as artifacts in a historical preservation project, which once again attempted to both physically and culturally remake the land, reveals a complex interplay between landscape and history and suggests the ways that this relationship is mediated by visual representation and contemporary viewing practices.

“A Critical Moment”

Edwin Deakin arrived in San Francisco in 1870, just one year after the Central Pacific Railway connected California to the rest of the continent (fig. 2). He completed his first mission paintings that year before moving to the city permanently in 1871. Born and raised in England, Deakin immigrated to the United States in 1856, settling first in Chicago before heading west to pursue his fortune. The artist never received a formal art education: in England, he was an apprentice furniture japanner, while in Chicago he dabbled in the booming photography industry, hand coloring photographs and using tintypes to paint portraits of Civil War soldiers.

Deakin turned to painting full time in 1867. He became well known in the increasingly competitive San Francisco art world for his prolific output of landscape, still life, and genre subjects. The artist was one of many flooding the city in pursuit of patrons in this period. The new wave of settlers migrating from the East Coast in the decades following the Mexican-American War (1846–48), the Gold Rush (beginning in 1848), and California’s statehood (1850) may not have had the fortunes of the previous generation’s railway barons, but nevertheless they looked to art to establish themselves in society. San Francisco was California’s unparalleled art capital: the San Francisco Art Association (founded in 1871) legitimized the city as a cultural center, while the California School of Design (1874) offered an academic education to West Coast artists for the first time. Prominent private art associations like the Graphic Club and Bohemian Club followed; Deakin joined both.[9] Rapidly improving communication and transportation networks enabled artists to travel and to send their work to East Coast and European exhibitions and dealers, as Deakin did throughout the 1880s. The artist traveled widely across the United States and Europe, while back at home the local press boasted about his submissions to the Paris Salon.[10]

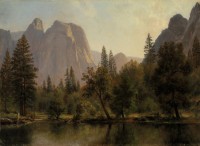

The landscape was by far the most popular subject for California’s quickly growing community of professional artists, amateur tourist sketchers, and commercial image-makers. Deakin was no exception. His earliest California subjects show the strong influence of German-born Hudson River school member Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902; figs. 3, 4), whose presence in San Francisco in the early 1870s also attracted prominent landscapists such as William Keith (1838–1911) and Thomas Hill (1829–1908). Like those artists, Deakin’s views of Mount Shasta, Lake Tahoe, and Yosemite Valley employ a dramatic visual language that contemporaries called “picturesque” to capture the untouched beauty and grandeur of California’s natural wonders. The solitary viewpoints, peaceful, smooth lakes, and deep, quiet valleys subordinate modern culture to a seemingly eternal nature even as they sell the potential of the vast West to post–Civil War tourists and settlers.[11]

Deakin’s first mission paintings depart from this aesthetic. In his first effort, Mission Dolores and the Mansion House (1870; fig. 5), the mission is quite at home in Victorian San Francisco with figures young and old inhabiting the scene. Early pictures of Mission Santa Barbara and Mission San Buenaventura likewise integrate the buildings comfortably into their landscapes. Others merely include a whitewashed mission wall as the backdrop for a still life, often an arrangement of lush grapevines. These early subjects made Deakin’s reputation, for good or ill: much to the artist’s consternation, they were popular enough to be frequently forged. Quoted by the San Francisco Examiner in 1889, he mourned seeing “fifty copies” of his Mission Dolores “placarded” around the city.[12] He would eventually return to the more dramatic picturesque approach in his 1897–99 mission project. These later views are irresolutely empty, the buildings in near ruins. If art historian Angela Miller has argued that Deakin’s colleague Bierstadt used the picturesque as a moral statement about nature as a retreat from society, “a way out of history” in the context of the Civil War, then I argue that Deakin deploys the picturesque as a way into history.[13]

According to contemporary critic Paul Shoup, Deakin emerged at “a critical moment” in the missions’ history to supply a “complete record of the appearance of these monuments to the strength of faith.”[14] Interested parties in Deakin’s time agreed that significant advances had been made to conserve California’s natural beauty, at least partly due to the work of artists such as Bierstadt. The preservation of California’s cultural heritage was another story, however, and for the still relatively new white, Anglo-American settlers of the state, the sense that they had no cultural heritage in the region was perhaps an even bigger threat.[15] Author Robert Louis Stevenson expressed this anxiety, noting in Across the Plains (1892) his impression that “Physically the Americans have triumphed; but it is not entirely seen how far they have themselves been morally conquered.”[16] While the East would no doubt remain British at heart, he continued, this was much less certain in California, where Mexican and Chinese histories—and, for that matter, their presence—were so strong. Deakin undertook his mission series with a self-conscious awareness of a much larger movement in the final decades of the nineteenth century to actively construct a history for the state so that it might have a bright future. This history was intimately connected to the physical and visual transformation of the landscape over time. It was also, as Stevenson suggests, explicitly racialized.

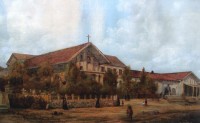

The origins of Deakin’s project are unclear. In November 1897, the San Francisco Chronicle announced the artist’s aim to “undertake, under the patronage of some wealthy man, a series of works which will perpetuate for all time the California missions, fast falling into decay.”[17] The same article falsely credits Deakin as the first artist to complete a full set of pictures of the twenty-one missions. Painters Henry Chapman Ford (1828–94) and Oriana Weatherbee Day (1838–86) each accomplished the goal in 1883 and 1884, respectively (fig. 6), while Carleton Watkins (1829–1916) produced a series of mission photographs in 1876. German-US artist Edward Vischer (1809–78) beat them all to the punch with a set of drawings published as a souvenir album as early as 1872.[18] (Deakin countered these earlier claims by saying that he had had the idea to complete the project in 1870.) Innumerable other painters, photographers, and sketchers, not to mention producers of popular visual culture, extended their attention to individual mission subjects through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. By contrast, there were few representations of the missions created while they were in actual use, and only a small number more from California’s Mexican years. These early efforts were produced by soldiers, sailors, and topographical artists in the employ of military and trade ventures; others can be found in illustrated travel narratives. Deakin drew directly and indirectly on all these sources for his own project.[19]

As the most visible reminders of California’s past, the missions held special currency in an increasingly romanticized historical narrative based on the state’s Spanish heritage. A well-told story, the mission system was founded by Father Junipero Serra in 1769 to extend the territory of New Spain up the West Coast from Mexico and expand Spanish control over the Native American inhabitants of the region. The missions quite literally transformed the California landscape by dividing it into well-defined parcels and introducing European farming practices. Through their common architectural features and prominent presence up and down the coast, the missions united the diverse geographies of the state, physically and visually claiming the land for Spain.[20]

Geographically isolated from both the rest of North America and from New Spain, the missions were essentially self-ruling until Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821 and passed the Act of Secularization in 1833. During this time, the landscape was reconfigured once again through the expansion of the rancho system. The subsequent Mexican-American War, Gold Rush, and granting of US statehood to California quickly and irrevocably transformed the region physically and culturally, with an influx of US settlers displacing Spanish, Mexican, and Native American populations. Over the course of these decades, the twenty-one missions and their lands passed into private ownership and met diverse fates. While several were returned to the Catholic Church beginning as early as the 1850s, the ravages of time and nature left others in varying states of ruin. Many were left to serve as homes for cowboy-robber gangs and Gold Rush squatters, or to function as stables, lumber warehouses, soldiers’ barracks, and, in the case of the mission at San Luis Rey, a liquor store. A small few were destroyed by natural disasters.[21]

The mission revival of the later nineteenth century took shape through the popularization of novels such as Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona (1884) and the cultural advocacy of figures such as Charles Fletcher Lummis (1859–1928). A growing fashion for mission-influenced architecture and design made the Spanish colonial style increasingly visible in public buildings and private homes across California; it became effectively state sanctioned when used for the California state buildings at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. Deakin himself built a mission-style home and studio in Berkeley, where he settled in 1890 (fig. 2). The missions were believed to be an especially suitable foundation upon which to stake a historical claim. Their connotations of faith, community, harmony between man and nature, and hard work before the age of industrialization formed a useful moral foundation for a narrative that sought to provide an appropriate cultural lineage for a new generation of Anglo Californians. Visual culture encouraged the movement, disseminating it widely through images in publications like Lummis’s magazine, Land of Sunshine.[22] Preservation of the missions themselves began slowly and in a scattershot way, picking up steam in earnest with the establishment of the Association for the Preservation of the Missions in 1880s and Lummis’s Landmarks Club in 1895 (both centered in Los Angeles). Many women’s philanthropic groups formed around the issue; indeed, critic Pauline Bird credited to Deakin specifically the vogue for preservation among Bay Area women’s clubs, particularly those advocating for the restoration of the Camino Real. Beginning in 1902, the rebuilding of this “royal road” once again brought the missions together, physically and imaginatively uniting the California landscape in a single geographic system and single historical narrative.[23]

The Pen and Scissors Man

Deakin’s series did much the same work for its turn-of-the-century audience, visually reuniting a system previously seen to be fragmented. The twenty-one paintings share a limited palette and polished finish. With one exception, they are horizontally oriented, and most show a single building set at an angle in the landscape. A neglected dirt road often cuts diagonally across the foreground. The same green fields, dirt paths, and mountain ranges provide the background for nearly all the images; the artist does not distinguish between the diverse regional geographies of northern, central, and southern California. The buildings themselves are shown in varying states of neglect, from the well-maintained church at Santa Barbara to the dilapidated walls of Soledad (figs. 1, 7).

Picturesqueness was the quality contemporary reviewers singled out most frequently in Deakin’s mission series; it remains the lens through which the artist’s work is viewed today.[24] Given his English upbringing, Deakin must have been familiar with the aesthetic tradition; certainly, his viewers directly connected his family background and chosen stylistic approach. “Love of the old, the picturesque, and the romantic came to Mr. Deakin in the earliest youth, when, as a boy in England, he wandered among the ruins of churches and castles, dreaming of valorous deeds of bygone heroes, and, in fancy, weaving stories and pictures to fit the hallowed scenes,” wrote Pauline Bird in 1904. “It is not to be wondered at that . . . the crumbling walls of the Missions, the tender sentiment that clung about them, with their Old World air of peace and restfulness, should awaken anew his youthful devotion to the historic past.”[25] Bird could well have been describing Deakin’s representation of the mission at Soledad: the painting’s warmly toned juxtaposition of the crumbling stone of the mission walls against the monumental mountains that form the background draw the viewer’s attention to the long passage of time. But the credibility Bird and her fellow critics attributed to Deakin and to his mission subjects was based on more than the artist’s firsthand experience sketching the missions. Rather, it was his use of an aesthetic category associated with Europe (and perhaps especially with Britain) to elevate a specific regional landscape and history to a supposedly universal ideal that made his work so effective in the project of shaping and preserving a narrative of California’s cultural inheritance.[26]

It is somewhat unclear, however, just what “picturesque” meant to Deakin’s audience at this time. The style was, after all, considerably out of date for Californian artists, who had moved on to impressionist-inspired canvases by the 1890s.[27] Evidently the label still held currency more than a century after writers such as William Gilpin and Uvedale Price established the visual and perceptual conventions of the term: where beautiful and sublime landscapes were smooth and contained, vast and terrifying, respectively, the picturesque found middle ground in landscapes characterized by roughness, asymmetry, and a variety that engaged the viewer’s eye in playful visual exploration. Looking again at Deakin’s representation of the mission at Soledad, we see a number of picturesque conventions invoked. The alternating patches of green grasses and brown dirt in the foreground, for example, lead the viewer rhythmically through the landscape, encouraging discovery of the wealth of detail provided by the artist. The rough texture of the walls, both their surfaces and the uneven line of the structure itself, delivers even more of the visual variety that picturesque viewers craved.

And yet, there is also much that departs from the traditional picturesque in this image as well. The sheer barrenness of the ruins seems to exceed picturesque convention, which favors quaint dishevelment over outright destruction. The overwhelming emptiness of the canvas, the almost anti-human character of its landscape, suggests a mode of viewing more in line with a traditionally sublime aesthetic. In this respect, Deakin’s work can be seen as not just a product of his British upbringing, but specifically of his transatlantic background. The picturesque and sublime were, like the artist himself, mobile and flexible: over the decades and as they were adapted and translated to new far-flung regions of the world, the lines between these aesthetic categories blurred and became unstable. Perhaps a more consistent feature of the picturesque, then, was an understanding of the landscape as an image in itself, to be viewed in relation to other images. Initially associated with the work of French baroque artist Claude Lorrain, any given landscape’s relative picturesqueness could be judged on how closely it accorded to an already-established set of imagery. In this sense, the picturesque was what art historian Nicholas Green calls “a technology of perception,” a learned way of seeing that conformed to preconceived aesthetic norms and ideological meanings.[28]

Through his engagement with the picturesque, Deakin participates in an aesthetic tradition used to visually manage potentially threatening landscapes, from the discourse’s origins in the context of rural workers’ riots in enclosure-era Britain, to the work of European colonial artists who deployed the aesthetic to make visual sense of the empire’s diverse territories. Numerous scholars have argued that the picturesque visual language made those landscapes legible, safe, and desirable to white, bourgeois, metropolitan audiences.[29] Art historian Katherine Manthorne examines these dynamics in the specific context of nineteenth-century California, proposing the term “Pan-American picturesque” to describe landscape painting trends in California and Mexico after the birth of the railroad: “Imprinting its civilizing stamp on the terrain, the picturesque mode tamed or homogenized [the land], making it more open to appropriation. In their poetic landscapes, artists were creating a body of work that unified rather than differentiated the lands that were politically demarcated as Mexico and California.”[30] In Deakin’s work, the physical transformations of the natural landscape brought about by colonization find a parallel in the artist’s own intensive and deliberate efforts to visually transform the land to align it with the established aesthetic expectations of his audience.

Recalling the picturesque tourists of an earlier era, contemporary critics praised Deakin’s rigorous practice of sketching on site, ascribing to his work both a strong sense of documentary truth and a skillful perfecting of nature. “Journey after journey has been made to each mission,” wrote Paul Shoup in 1900, “innumerable sketches have been drawn; weeks have been spent in studies of wall and tower, and every painting has had its changes to conform to some improved conception.”[31] Deakin made over 150 sketches of the missions (fig. 8), using a drawing grid to systematically record their appearances and natural surroundings. Reviewers had responded ambivalently to this level of carefully observed detail in his earliest landscape work; while some allied him with the truth-to-nature goals of British critic John Ruskin, others criticized the rote, “mechanical cast” of the images.[32] In this respect, Deakin found himself squarely in the center of critical debates about mid-nineteenth-century US landscape painting.[33] By contrast, the mission paintings received unanimous praise on this front. Deakin’s image of the mission at San Juan Capistrano (fig. 9) is a good example: each brick in the wall, each crack in the dry earth, each flower in the tree in the foreground is individually delineated. The sense of veracity given by the details contribute to the impression that they must have been viewed onsite.

In turn, the apparent authenticity of Deakin’s detailed sketch practice reinforced the understanding that the artist’s works were important historical documents that testified to California’s heritage. Awed tales of his encounters with outlaws and wild animals during his quest to capture each mission in person contributed to the project’s critical success, with one critic concluding that the story of Deakin’s “struggles and sacrifices to perpetuate these missions before the destroying hand of time and vandalism of generations of robbery and abuse had utterly obliterated them is as noble a one and as pathetic as any of the many such stories in the realms of art and letters.”[34]

And yet, Deakin’s sketches are by no means directly reported. When examined closely, the sketches that initially seem to attest to the artist’s careful documentation of the missions in fact reveal that his working method involved a more complex visual mediation of his subject matter. Significantly, the textual annotations that supplement the sketches note changes to be made in the final product. In his sketch for San Juan Capistrano, words and phrases such as “white flowers,” “fine sand,” and “bits of tile and brick” substitute for visualized landscape features, suggesting that the final image will be (and indeed was) enhanced in line with picturesque conventions (fig. 8). This semiotic movement between text and image shows Deakin’s use of types, rather than the careful observation of nature for which he was celebrated, to compose the final painting. Moreover, in addition to preparatory work for the final images, Deakin’s sketch scrapbook frequently singles out various picturesque elements for attention—a crumbling doorway, a silent bell, a hollow niche, tiles falling off the roof. Altogether, the scrapbook reads as a book of motifs, ready to be plucked from the pages and assembled by an enterprising artist (fig. 10). A reviewer for the San Francisco Chronicle noted this tendency in Deakin’s work, writing, “He uses some of his sketches as the pen and scissors man his paragraphs.”[35] This reference to Deakin as an editor makes literal the idea of the picturesque as a visual language with its own underlying grammar of established components to be mixed and manipulated in the service of the message to be communicated.

Deakin incorporated more than his own sketches into the final works, drawing instead from a wide variety of sources both general and specific. First, the artist looked to an established and remarkably consistent set of tropes used to represent California and the Spanish Revival: images of the state’s temperate climate, its citrus- and palm-filled landscapes, and the missions themselves dominated fine art and popular visual culture alike in the decades around the turn of the twentieth century. Discussing photography in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Los Angeles, Jennifer Watts describes how the missions in particular conform to what she calls an “aesthetic of the ‘best view,’” wherein certain vantage points were consistently privileged over others. She points to the almost total uniformity of representations of Mission San Gabriel as one example.[36] Deakin’s own version, which highlights the buttresses of the south wall, the bell tower, and the stairs, is clearly influenced by this body of imagery.

Deakin’s appropriation of specific images is even more striking. Many of his views are direct copies of other artists’ paintings and photographs.[37] Given that several missions were, in 1897–99, nearly or completely destroyed, Deakin was forced to rely on secondhand accounts for some paintings. The artist’s sources included daguerreotypes made by James M. Ford in the mid-1850s of Missions Santa Clara and San José (both destroyed in previous earthquakes; the former rebuilt as Santa Clara University; figs. 11, 12), a painting by Léon Trousset of Mission Santa Cruz (in ruins by the 1850s; figs. 13, 14), and photographs by Carleton Watkins of Mission San José and Mission San Luis Obispo (figs. 15, 16). Deakin’s sketches of Mission San Rafael, which had been completely destroyed, reveal the extent to which some of the final paintings were imagined recreations (figs. 17, 18). One is but a landscape sketch of the surrounding hills labeled “about the spot of the mission.” A small, hastily sketched building with a cross marks the location. In another sketch of San Rafael, a large tree in the foreground obscures our view of the church, as if to comment on the frustrating inability of study from nature to deliver the full picture.

And so, the Deakin mission paintings are indeed closely observed studies—of other images. The artist’s approach speaks to a fundamental operation of picturesque discourse: the reciprocal relationship between the landscape that “looks like a picture” and the picture that then looks appropriately “picturesque.” In his own time, Deakin’s visual adaptations were not cause for scorn, but rather respect that the artist would go to such lengths to attempt an accurate representation. Deakin himself acknowledged his borrowings in his book, while contemporary reviews described his process, documenting his sources to verify the truth of the works. As such, the perceived fidelity to his subjects that elevated Deakin’s work to the status of historical artifacts seems to have been as much about faithfulness to looking like a picture—whether to an established body of imagery, or to a very specific picture—than anything else.[38] The mission pictures were effective in formulating a narrative of cultural heritage and historic preservation not because they were true to what the landscape and its monuments actually resembled in 1897–99, but rather because they were faithful to a century or more of ways of visualizing said landscape.

“Better a Heap of Broken Bricks”

Deakin’s engagement with the picturesque was more than a visual framework for making the landscape legible and appealing to his audience; it was also about endowing the landscape with an appropriate historical lineage. In Deakin’s work, the California missions appear as neglected monuments of a long ago past, US versions of Turner’s Tintern Abbey (1794) or Constable’s Hadleigh Castle (1829). Critic Robert L. Hewitt even compared the artist to Piranesi capturing “the vanishing glories of Rome.”[39] Accordingly, Deakin’s missions appear almost exclusively in varying states of ruin, with crumbling roofs and walls. To further locate the buildings in the past, the artist exhibited his view of Mission San Diego (the first mission established in 1769; fig. 19) together with lines from English poet Charles Kingsley’s 1848 “Old and New”: “So fleet the works of men, back to their earth again; / Ancient and holy things fade like a dream.” In the image itself, a small fire in the foreground has been left to burn out. The parallel between the trace of smoke indicating the past presence of man and the mission itself as remnant of a previous age is not especially subtle.[40] In emphasizing the ruined quality of the missions, however, Deakin was once again forced to adapt his sketches and source material to better shape a preferred narrative. Not all of the missions were, in fact, in ruins. But by relegating the Spanish mission system to the pages of history, Anglo-American California gave itself a distinctive past and, perhaps more importantly, an uncontested present and future.

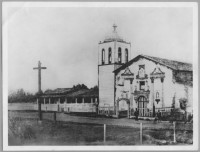

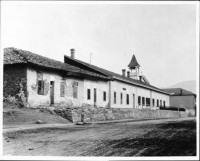

Even as preservationists mourned the state of affairs, the fact that the missions were in ruins was a large part of their appeal and their political utility as historical symbols. Even more troubling to heritage advocates than outright neglect were the modern renovations to many missions made piecemeal by local priests and congregations. With religious continuity and modernization taking precedence over cultural heritage, these early efforts sometimes resulted in additions such as New England–style wood siding and pointed steeples. These became the target of much criticism by a later generation of preservationists.[41] Paul Shoup, writing in Sunset magazine in 1900, for example, argued “better a heap of broken bricks than a wall that no mission builder ever intended should be smooth . . . Better a glorious memory of the quaint and graceful art of the Franciscan builders than the bevel edged, whitewashed, planed practicability of the saw, hammer, and brush.” He continued, “Our restoration should be truthful, else, afterwhile, we will wonder at the work of Edwin Deakin as the creations of the artistic imagination instead of a true presentiment of the California missions.”[42] Deakin’s series shows no evidence of these early renovations. The mission at San Luis Obispo, for example, saw its façade covered in white clapboard and a church steeple added to the bell tower in the 1870s and ’80s; these changes remained in place when Deakin was painting, although they are not present in the finished work (figs. 20, 21). Deakin’s representation of Mission Santa Clara reveals similar omissions (figs. 11, 12).

Deakin’s historicization of the missions appears most clearly through the total absence of human figures: most of the missions have been quite literally left to the birds.[43] In many paintings, the foreground roads are empty and look like they have been for many years. They are overgrown with shrubbery, with no wagon grooves, footprints, or horse trails. But even in the late nineteenth century, several missions persisted as spaces of worship and work for Hispanic and indigenous communities. In the case of Mission San Buenaventura, for example, contemporary photographs show the mission in a bustling town center. Deakin’s painting (fig. 22), meanwhile, excises all signs of contemporary life, placing the mission in the countryside. Of all twenty-one paintings, it alone is oriented vertically so as to accommodate this imagined relocation. Here, Deakin departs from both the traditional picturesque approach, which frequently includes staffage figures in the form of happy peasants or hiking day trippers, and from his contemporaries’ mission subjects: compare Oriana Weatherbee Day’s lively representation of Mission Soledad with Deakin’s own bleak scene (figs. 6, 7). Some of the artist’s preparatory sketches do show farmers and others milling about the buildings. The monks in his sketches of Mission San Luis Rey, for example, are particularly engaging (fig. 23). The represented figures were friars from Zacatecas, Mexico, who in 1892 had come to start a seminary and under whose auspices modern renovations were proceeding; as such, they provide strong evidence for a continued living presence at the mission that is entirely absent from Deakin’s final painting.

Comparing Deakin’s paintings to his visual sources shows that this de-peopling was a deliberate change: compare his image of Mission Santa Cruz with the Trousset painting on which it was based, for example (figs. 13, 14). The same holds true even when Deakin looked to his own earlier work as a source: the difference between the artist’s 1870 painting of Mission Dolores and the 1897–99 version is stark (figs. 5, 24). Where the first iteration shows the mission as a center of public life, with a well-maintained roof, fence, and cemetery, the second lacks any human presence. Though the building’s position remains similar, the figures have been erased, replaced by moss growing on the roof and vegetation slowly enveloping the front fence.

Art historian John Ott has described Deakin’s work as “reconstruct[ing] the missions in a state of decay.” Describing a similar tendency in Deakin’s colleague Henry Chapman Ford, Ott argues that the latter artist’s works “do not so much reconstruct Spanish culture at its peak as they preserve and taxidermy its cadaver for Anglo delectation. Drained of historical specificity, set in the present, and vacated of intervening figures, these images foster a more direct relationship with viewers and . . . encourage them to identify personally with the iconic remnants of the Californio past.”[44] Unlike Ford’s, however, Deakin’s images of San Buenaventura, Santa Cruz, and Mission Dolores are not exactly set in the present. But neither are they set in the original mission period. Other visual qualities also suggest a peculiarly arrested sense of time. No weather, for example, is apparent in Deakin’s paintings: no sunrises or sunsets, no oncoming storms, nothing to suggest a particular hour of day or the passage of time. The only indications of atmosphere are the sunlit sky and Constable-like clouds, though Deakin’s work shows none of the animation of his more famous colleague’s studies.[45] Each painting is decidedly still: the grass does not rustle, the trees do not sway in the breeze. The bells, often prominent in the composition, hang silent. Even the birds, landing amid the abandoned buildings in several of the works, do not seem to fly so much as hover in place. In rebuilding the missions neither to their current-day realities, nor to the most flourishing moments in their pasts, but rather, to their most perfect states of ruin, Deakin displaces the missions outside of historical time. Even as the mission pictures operate under the pretense of preserving and documenting history, they exceed that history, simultaneously representing the past, present, and perhaps future.

Deakin’s manipulation of time was necessary because the distinctively Spanish Catholic nature of the missions’ history required some rhetorical negotiation by the largely Protestant Anglo-American preservationists attempting to claim it as their own. They did so in contradictory terms, at once elevating the missions as specific evidence of California’s Christian and European heritage and incorporating them into a “universal” narrative of Western civilization divorced from the historical facts of the missions’ founding: “The missions belong not to the Catholic Church,” Charles Lummis implored readers of his Land of Sunshine, “but to you and me. Let us save them—not for the church, but for humanity.”[46]

Deakin’s images foreground the religious nature of the mission landscapes by focusing on the churches to the almost total exclusion of the other parts of the mission complexes.[47] In one case, the landscape includes a hint of narrative with expressly Christian connotations (fig. 25). In Deakin’s painting of the mission at Carmel, sheep stand at the entrance to the church next to a cross acting like a shepherd’s staff, leading the lost flock out of the hills and into the welcoming open doors of the mission. More generally, though, the California landscape was itself viewed through the lens of the pastoral, or even paradisiacal: a nourishing, bountiful new Eden in the West. Elizabeth Kryder-Reid draws a comparison between the invention of the mission garden in the latter decades of the nineteenth century and European monastery gardens of the medieval period, both conceived as metaphorical spaces in which faith could bloom and prosper.[48]

John Ott argues that the collapsing of diverse histories into a Spanish and religious narrative was an attempt to “whiten” California’s history. “‘Spanish’ was more comfortably European,” he writes, “a designation for ‘white ethnics’ not significantly lower than Anglo-Saxons in period cultural hierarchies.”[49] In this line of thinking, the period of California’s Mexican rule could be excused as nothing more than a brief disruption in an otherwise stable, peaceful, and happy timeline. Furthermore, this minor aberration in history was a convenient place on which to pin the blame for the state of the missions. The understanding that the “correct” timeline would be saved and restored by a new generation of white, Anglo-American settlers is a complicated discourse that incorporates wider late nineteenth-century understandings of the colonial salvage paradigm. It was also a discourse that avoided the potentially troubling Spanish displacement of Native American populations in favor of disapproval directed at Mexican interventions, not to mention erasing the fact that, as Robert Louis Stevenson suggested, Anglo dominance was hardly a given in this still contested period.[50]

Conversely, understanding the mission landscapes as paradisiacal extended the state’s history well beyond its recent Mexican and Spanish past, presenting the possibility of, as Sheri Bernstein has said, “mythologizing the state as a Mediterranean haven along the lines of ancient Athens or Rome.”[51] Here, the ruined missions stand not as a New World Tintern Abbey, but a Californian Acropolis, vacated of their specific religious significance in favor of a supposedly universal historical character: not Eden, but Arcadia. The California landscape as the cradle of a new civilization—“an incubator for a better humanity”[52]—had clear political, cultural, and racial implications in a moment when the western United States was perceived (and indeed marketed) as a refuge for white East Coasters fleeing west in the face of urban class and race mixing that accompanied increasing immigration and post-abolition migration. The revival of Spanish themes in this context was about more than nostalgia or anxiety about the disappearing past. Rather, it was a key feature of modern California’s vision for the state’s present and future.[53]

Finally, the collapsing of time in Deakin’s mission series was an appealing way for the artist to deal with the problem of how to achieve the desired effect of historical accuracy when history itself was unstable and ill-defined. The missions themselves were, after all, built at different times, stretching over half a century of construction, from the first effort in San Diego in 1769 to the final San Francisco Solano in Sonoma in 1823. Even before the moment of secularization, the mission system’s success was extremely uneven, largely determined by each mission’s individual physical landscape and its predisposition toward flooding, fire, and earthquakes: some of the first missions had already been destroyed, relocated, rebuilt, or abandoned before the final ones were even built. Moreover, the majority of the grand churches painted by Deakin were not built at founding but were rather the product of later renovations. In essence, if Deakin’s images ask their viewers to recall a distant and vanishing past to advocate for its preservation, in reality there was no single coherent time to remember or return to. In this respect, the artist’s work participates not only in wider discourses of the picturesque as applied to the colonial landscape, but to colonial discourse more generally and the ways in which it enacts narratives of time, history, and progress: the colonial cannot be modern, it must always be displaced to a fantasy past. In this way, the Anglo-American triumph of civilization in California is positioned as inevitable, even as the drastic physical transformation of the land wrought by successive waves of colonization is made invisible through its picturesque aestheticization.

Conclusion

At least part of the historical value of Deakin’s project was its conception as exactly that: a project. Deakin’s work was intended to be understood as a whole greater than the sum of its parts: the entirety of the California landscape and its history arranged as an image for the benefit of the viewer and his or her gaze. The works were originally exhibited in the Maple Hall of San Francisco’s Palace Hotel. Built in 1875 as the largest and grandest hotel in the western United States, the Palace was itself a symbol of progress and civilization in California.[54] The exhibition was geographically organized, and it included a large handmade map showing each mission’s location. The pictures were further united through specially designed frames, each embellished with Christian symbols, such as crosses, nails, and thorns. Seen together, they encouraged viewers to adopt a picturesque gaze, evaluating the relative beauty of the different buildings and landscapes as compared to one another and to preconceived expectations. A full tour of all twenty-one missions was unnecessary; instead, one could conveniently see them all in a hotel lobby in San Francisco.

Should a viewer choose to undertake the trip themselves, Deakin supplied a portable guide in the form of a book. His The Twenty-One Missions of California was just one among a flurry of illustrated books about the missions published around the turn of the twentieth century, many written with preservation efforts in mind. Like others of its type, Deakin’s text sits uncomfortably between genres: part history, part tourist guide. Though it includes short descriptions of each mission’s history, the book is structured geographically, tracing the missions from south to north as opposed to in the chronological order of their construction. As a history, Deakin’s book showed its viewers what to look at, while as a picturesque illustrated tourist guide it taught them how to look.

This conceptualization of the works as a united and reproducible set made possible an understanding of both the varied and ever-changing geography of the mission landscapes and the non-linearity of mission history as consistent and coherent. If the original establishment of the missions intended to visually and spatially join a large and diverse territory under Spanish control, then Deakin’s exhibition and publication of the paintings as a set enabled a contemporary visual unification of the same territory, functioning to bring distant times and spaces together in one scheme, subject to the viewer’s own possessive gaze. Ultimately, Deakin refused to separate the works, insisting so strongly that the pictures be kept together that he was unable to sell them in his own lifetime.[55]

After the exhibition, critic Pauline Bird proclaimed hopefully that Deakin would open “the eyes of Californians to the urgency of preserving these landmarks.”[56] In his own call for the state to purchase the set in the face of competition from the University of Illinois, Paul Shoup slips between what exactly needs saving: the missions themselves or Deakin’s paintings of them. “The missions are still one of California’s chief charms,” he writes, “but we must remember that today the twenty-one, as built, exist only on canvas, and only on one painter’s canvas; if California of today permits the priceless heritage that Edwin Deakin has created for her to pass from her possession, her grandchildren will not only mourn the loss but blush for the ignorance that permitted it. . . . We have saved the Big Trees; but we have no Congress to help us save the mission pictures.”[57] Here, the mission myth replaces its origins entirely.

The paintings were valuable to Shoup because they acted as historical evidence of a cultural legacy that would help to shape California’s future (and as the future president of Southern Pacific Railroad, he was an interested observer). Critic Robert L. Hewitt agreed, writing, “It will readily be seen that the interest of the canvases is largely historical.” He later continued, “It is quite outside the province of this article to discuss these paintings purely as works of art. They fall into a category of their own. They were designed as faithful transcriptions of vanishing monuments, and hence the artist has taken no liberties whatever with his subjects. He has simply selected the best views of the different structures and has been faithful in all his work to fact.”[58] But as I have shown, the sense of authenticity contemporaries attributed to Deakin’s work meant something beyond pure visual mimesis.

Rather, what Deakin’s series offered its viewers was faithfulness to an established way of seeing the California landscape and, moreover, to a way of seeing that invested said landscape with a cultural heritage appropriate to the needs of Anglo-American settlers attempting to claim it as their own. In Deakin’s day, California’s landscape was once again being transformed, this time in the service of historical preservation and the tourist industry. Increasingly, historical preservationists turned to the visual imagery of Deakin and his colleagues as sources for their own work. That Deakin’s careful visual remaking of the landscape might itself be put to the use of a physical remaking of the landscape speaks strongly to the complex relationship between landscape, history, and visual culture.

[1] The conservation project was completed in 2016. Monica Orozco, “Conserving the Art of Early California,” Santa Barbara Mission Archive-Library, published April 29, 2014, https://sbmal.wordpress.com/2014/04/29/conserving-the-art-of-early-california/.

[2] Pauline R. Bird, “The Painter of the California Missions,” The Outlook 76 (1904): 74; Paul Shoup, “An Old Story in Crumbling Walls,” Sunset 16 (April 1900): 244.

[3] Edwin Deakin, The Twenty-One Missions of California (Berkeley: Murdock Press, 1899).

[4] For example, “Local Exhibitions of Unusual Interest,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 6, 1900.

[5] Robert L. Hewitt, “Edwin Deakin, An Artist with A Mission,” Brush and Pencil 15, no. 1 (January 1905): 8.

[6] Elizabeth Kryder-Reid, California Mission Landscapes: Race, Memory, and the Politics of Heritage (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016). For the most complete recent survey of visual and material culture relating to the missions, see Edna E. Kimbro and Julia G. Costello, with Tevvy Ball, The California Missions: History, Art, and Preservation (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 2009). See also a number of the essays in Katherine Manthorne, ed., California Mexicana: Missions to Murals, 1820–1930 (Laguna Beach, CA: Laguna Art Museum and University of California Press, 2017); as well as Joan Stern et al., Romance of the Bells: The California Missions in Art (Irvine, CA: Irvine Museum, 1995); and Karen J. Weitze, California’s Mission Revival (Santa Monica, CA: Henessey and Ingalls, 1984). A recent trend in scholarship shows interest in the visual culture of the missions as evidence of cross-cultural networks in line with wider scholarly interventions in colonial Latin American art and understandings of the Pacific Rim. See, for example, J. M. Mancini, “Pedro Cambón’s Asian Objects: A Transpacific Approach to Eighteenth-Century California,” American Art 25, no. 1 (2011): 29–51, doi:10.1086/660031.

[7] The literature on the relationship between landscape painting, national identity, and the settlement of the United States is immense. Select foundational texts include Albert Boime, The Magisterial Gaze: Manifest Destiny and American Landscape Painting, c. 1830–1865 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991); Angela Miller, The Empire of the Eye: Landscape Representation and American Cultural Politics, 1825–1875 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993); Barbara Novak, Nature and Culture: American Landscape and Painting, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); and William H. Truettner, ed., The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820–1920 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991). Scholars have also expanded this discussion beyond painting to include photography, for example, Joel Snyder, “Territorial Photography,” in Landscape and Power, ed. W. J. T. Mitchell (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 175–201; and, more recently, print culture, such as Matthew N. Johnston, Narrating the Landscape: Print Culture and American Expansion in the Nineteenth Century (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016). Recent examples of scholarship on the transnational development of US landscape painting in the nineteenth century include Peter John Brownlee, Valéria Piccoli, and Georgiana Uhlyarik, eds., Picturing the Americas: Landscape Painting from Tierra del Fuego to the Arctic (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015); Elizabeth Kornhauser and Timothy Barringer, Thomas Cole’s Journey: Atlantic Crossings (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018); and Andrew Wilton and Timothy Barringer, American Sublime: Landscape Painting in the United States, 1820–1880 (London: Tate, 2002).

[8] The most complete account of Deakin’s life and work is Scott Shields’s catalogue for a 2008 exhibition at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, CA, Edwin Deakin: California Painter of the Picturesque (Petaluma, CA: Pomegranate, 2008). Deakin’s mission project is also the subject of a short catalogue published by the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles (NHMLA) in 1966, Ruth I. Mahood, Paul Mills, and Donald C. Cutter, A Gallery of California Mission Paintings by Edwin Deakin (Los Angeles: County of Los Angeles Department of the Museum of Natural History, 1966). Both the Santa Barbara Mission Archive-Library and the Santa Barbara Historical Museum recently published reproductions of their respective sets of paintings. Other aspects of the artist’s career—his work in San Francisco’s Chinatown and his still life subjects—are explored in Anthony Lee, Picturing Chinatown: Art and Orientalism in San Francisco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001); and Shana Klein, “The Fruits of Empire: Contextualizing Food in Post-Civil War American Art and Culture” (PhD diss., University of New Mexico, 2015). Archival material is held by the Oakland Museum of California and the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM); Deakin’s sketch scrapbooks for the mission project are in the collection of the Seaver Center for Western History Research at the NHMLA.

[9] On Deakin’s participation in the Bohemian Club, see Lee, Picturing Chinatown, ch. 2. On patronage and the social contexts for art in San Francisco in this period, see especially John Ott, Manufacturing the Modern Patron in Victorian California: Cultural Philanthropy, Industrial Capital, and Social Authority (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2014). The art scene in other California regions where Deakin painted lagged until well into the 1890s, even as the land boom of the 1880s saw the population and wealth of the state increase rapidly. Los Angeles, San Diego, and Santa Barbara all attracted their fair share of artists like Deakin looking to paint the charms of the southern California landscape, but the cities lacked any substantial market, especially for the work of native Californian artists. On the art world in Los Angeles at the turn of the twentieth century, see Jasper G. Schad, “‘A City of Picture Buyers’: Art, Identity, and Aspiration in Los Angeles and Southern California, 1891–1914,” Southern California Quarterly 92, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 19–50, doi:10.2307/41172506.

[10] “Palette and Easel,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 6, 1879; “Palette and Easel,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 8, 1879.

[11] On Bierstadt in this context, see Angela Miller, “Albert Bierstadt, Landscape Aesthetics, and the Meanings of the West in the Civil War Era,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 27, no. 1 (2001): 40–59, doi:10.2307/4102838.

[12] “The Pirates of Art,” San Francisco Examiner, September 22, 1889.

[13] Miller, “Albert Bierstadt,” 40. The dynamic relationship between nature and history has also been explored in relation to the landscape work of Thomas Cole. See, for example, William H. Truettner and Alan Wallach, eds., Thomas Cole: Landscape into History (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994).

[14] Shoup, “An Old Story in Crumbling Walls,” 244.

[15] I use the term “white, Anglo-American” or “Anglo” throughout to designate this new generation of settlers; here, I follow scholars such as William Deverell, John Ott, and Phoebe Kropp.

[16] Robert Louis Stevenson, Across the Plains: With Other Memories and Essays (Leipzig: Bernard Tauchnitz, 1892), 95.

[17] The identity of this possible patron is unknown. “Holiday Hours in Artists’ Studios,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 28, 1897.

[18] “Holiday Hours in Artists’ Studios.” Perhaps the first to attempt a full series was artist and entrepreneur Henry Miller, who drew several missions in the 1850s with the aim of producing a panorama, though it seems this was never completed (Stern, Romance of the Bells, 87).

[19] The first oil painting of a mission subject is thought to be Ferdinand Deppe’s San Gabriel, ca. 1832–35 (Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach). Deppe (1794–1861) was a German naturalist who traveled extensively in Mexico and California to collect natural history specimens.

[20] The critical literature on the history of the missions is vast and has been well rehearsed elsewhere. For a sampling of recent trends in this scholarship, see the essays in Steven W. Hackel, ed., The Worlds of Junipero Serra: Historical Contexts and Cultural Representations (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018).

[21] This history has also been well rehearsed elsewhere, often verging into the realm of legend. The most complete account can be found in Kimbro and Costello, with Ball, The California Missions.

[22] An excellent body of scholarship relating to the cultural contexts of the Spanish and Mission Revivals exists, though little written from an explicitly art-historical perspective. In addition to Kryder-Reid, some of the most useful include Dydia DeLyser, Ramona Memories: Tourism and the Shaping of Southern California (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005); William Deverell, Whitewashed Adobe: The Rise of Los Angeles and the Remaking of Its Mexican Past (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004); Phoebe S. Kropp, California Vieja: Culture and Memory in a Modern American Place (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006); Kevin Starr, Inventing the Dream: California through the Progressive Era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985); and D. H. Thomas, “Harvesting Ramona’s Garden: Life in California’s Mythical Mission Past,” in Columbian Consequences: The Spanish Borderlands in Pan-American Perspective, vol. 3 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991), 119–57. On visual culture in this context, see Sheri Bernstein, “Selling California,” in Made in California: Art, Image, and Identity, 1900–2000, eds. Stephanie Barron, Sheri Bernstein, and Ilene Susan Fort (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2000), 64–101; Michael Komanecky, “‘The Treasures of Sentiment, the Charms of Romance, and the Riches of History’: Artists’ Views of California’s Missions,” in California Mexicana: Missions to Murals, 1820–1930, ed. Manthorne, 172–95; and Jennifer Watts, “Photography in the Land of Sunshine: Charles Fletcher Lummis and the Regional Ideal,” Southern California Quarterly 87, no. 4 (Winter 2005–6): 339–76, doi:10.2307/41172283.

[23] Bird, “The Painter of the California Missions,” 74. John Ott explicitly roots Bay Area women’s patronage of mission preservation efforts in contemporary understandings of race and culture by situating it in the greater context of white matronage of working classes and minorities in this period (Manufacturing the Modern Patron in Victorian California, ch. 6). On the revival of the Camino Real, see especially Kropp, ch. 2.

[24] Interestingly, few reviews used the exact term to describe his earliest landscape work.

[25] Bird, “The Painter of the California Missions,” 77.

[26] Timothy Barringer has called the picturesque and the sublime the “transatlantic inheritance” of US landscape artists like Thomas Cole (Picturesque and Sublime: Thomas Cole’s Trans-Atlantic Inheritance [New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018]). Also useful in this context is Kenneth Haltman, “Picturesque Nostalgia as Ironic Dislocation: Joshua Shaw’s Disruptive Visions of the Old New World,” Art History 34, no. 4 (September 2011): 696–713, doi:10.1111/j.1467–8365.2010.00842.x.

[27] Mission subjects were also popular among these artists, but they tended to concentrate on different aspects: small-scale vignettes of stone arcades and lush gardens were more likely to appear than the grand landscapes of Deakin’s work.

[28] Nicholas Green, The Spectacle of Nature: Landscape and Bourgeois Culture in Nineteenth-Century France (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990), 111.

[29] See, among others, John Barrell, The Dark Side of the Landscape: The Rural Poor in English Painting, 1730–1840 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980); Ann Bermingham, Landscape and Ideology: The English Rustic Tradition, 1740–1860 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986); Green, The Spectacle of Nature; Andrew Hemingway, Landscape Imagery and Urban Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992); Geoff Quilley, “Pastoral Plantations: The Slave Trade and the Representation of British Colonial Landscape in the Late Eighteenth Century,” in An Economy of Colour: Visual Culture and the Atlantic World, 1660–1830, eds. Geoff Quilley and Dian Kriz (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003), 106–28; Romita Ray, Under the Banyan Tree: Relocating the Picturesque in British India (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013); and Krista P. Thompson, An Eye for the Tropics: Tourism, Photography, and Framing the Caribbean Picturesque (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006).

[30] Katherine Manthorne, “Pan-American Picturesque: Railroad Travel and Artistic Tourism, 1870–1910,” in California Mexicana: Missions to Murals, 1820–1930, 138. Elizabeth Kryder-Reid argues that the invention of the mission garden in the later nineteenth century was immersed in similar power dynamics: a re-ordering of the physical landscape to align with the “powerful ideological naturalization of Western conquest and asserted racial superiority” (California Mission Landscapes, xi).

[31] Shoup, “An Old Story in Crumbling Walls,” 244.

[32] “San Francisco Art Association,” San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin, December 6, 1872. Deakin’s scrapbook at the SAAM includes a reproduction of George Richmond’s 1857 portrait of Ruskin. Microfilm reel 4201, Edwin and Robert Deakin papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

[33] Jennifer Raab, Frederic Church: The Art and Science of Detail (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015), 3–4. See also Miller, “Albert Bierstadt,” 44–45.

[34] Bird, “The Painter of the California Missions,” 77.

[35] “Brush and Pencil,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 22, 1874.

[36] Watts, “Photography in the Land of Sunshine,” 226.

[37] Anthony Lee shows that Deakin did much the same work of translating one image to another in his Chinatown pictures, here drawing on the work of photographer Isaiah West Taber (Picturing Chinatown, 91).

[38] Kryder-Reid discusses a similar response to the new mission gardens built in the final decades of the nineteenth century, which she argues visitors found believable because they looked like images of Spanish and Italian gardens reproduced in illustrated books (California Mission Landscapes, 83). More broadly, the strength of the Western landscape tradition depended on its visual consistency across various media. Joel Snyder, for example, has argued that US landscape photography and painting were mutually reinforcing through their use of established aesthetic conventions, painting giving photographers a way of looking at the landscape, and photography giving some of its perceived truth value back to painting (“Territorial Photography,” 185).

[39] Hewitt, “Edwin Deakin,” 1. Deakin himself compared the missions and European antiquities at least once. An undated pamphlet published by the California Art Gallery in the SAAM Deakin scrapbook, likely from the mid-1870s, reports that he exhibited “two pictures which hang near one, a view of the old Mission Church and the other a street in ancient London. Each subject is rich in suggestions and interesting by association as well as intrinsically attractive.” Microfilm reel 4201, Edwin and Robert Deakin papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

[40] The motif is repeated in his images of Missions San José and Santa Inés.

[41] First among them Charles Lummis, whose Landmarks Club advocated strongly for preservation rather than restoration, presaging modern debates around conservation (Kimbro and Costello, with Ball, The California Missions, 71–74).

[42] Shoup, “An Old Story in Crumbling Walls,” 245. William Deverell takes the whitewashing of adobe structures as a guiding metaphor for the Anglo-American erasure of Los Angeles’s Mexican history (Whitewashed Adobe, 7–8).

[43] A more practical reason might underlie the lack of people in Deakin’s work: because he was formally untrained, his contemporaries believed the artist to be unskilled at figure painting (“Edwin Deakin,” Evening Wisconsin, April 23, 1883).

[44] Ott, Manufacturing the Modern Patron, 221, 232.

[45] Deakin was familiar with the significance of his British predecessor. In an undated, uncited brief titled “An Exodus” included in Deakin’s SAAM scrapbook, a journalist describes the artist going to New York with his pictures, including “a copy of Constable’s Stormy Day being interesting from the story that, with the production of its original, the Claude Lorrain school received its death blow, artificiality thereafter giving place to realism, and Nature being painted as she is.” Microfilm reel 4201, Edwin and Robert Deakin papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

[46] Quoted in Kimbro and Costello, with Ball, The California Missions, 59.

[47] On this tendency in the mission myth generally, see Thomas, “Harvesting Ramona’s Garden,” 138.

[48] Kryder-Reid, California Mission Landscapes, 83, 154–67. On California as Eden in diverse contexts, see Bernstein, “Selling California,” 65; Deverell, Whitewashed Adobe, 4–5; Watts, “Photography in the Land of Sunshine,” 358–66; and Blake Allmendinger, “All about Eden,” in Reading California: Art, Image, and Identity, 1900–2000, eds. Stephanie Barron, Sheri Bernstein, and Ilene Susan Fort (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2000), 112–27. Jason E. Pierce extends this discourse to the Western US as a whole in Making the White Man’s West: Whiteness and the Creation of the American West (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2016).

[49] Ott, Manufacturing the Modern Patron in Victorian California, 219.

[50] Deverell, Whitewashed Adobe, 28.

[51] Bernstein, “Selling California,” 82. See also Kryder-Reid, California Mission Landscapes, 154–67.

[52] Watts, “Photography in the Land of Sunshine,” 222–23.

[53] Kropp, California Vieja, 4–5.

[54] Barbara Berglund, Making San Francisco American: Cultural Frontiers in the Urban West, 1846–1906 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007), 40–47.

[55] Hewitt, “Edwin Deakin,” 3.

[56] Bird, “The Painter of the California Missions,” 80.

[57] Shoup, “An Old Story in Crumbling Walls,” 245.

[58] Hewitt, “Edwin Deakin,” 3 and 4.