The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

The Rockies and the Alps: Bierstadt, Calame, and the Romance of the Mountains

Newark Museum, Newark, NJ

March 24–August 19, 2018

Catalogue:

Katherine Manthorne and Tricia Laughlin Bloom, with contributions by Patricia Mainardi and James M. Saslow,

The Rockies and the Alps: Bierstadt, Calame, and the Romance of the Mountains.

Newark: Newark Museum, in association with D. Giles Ltd., London, 2018.

176 pp.; 100 color illus.; bibliography; index.

$45 (hardcover)

ISBN-10: 190780496X

ISBN-13: 978-1907804960

When I was ten years old, my parents took my younger brother and me on our first summer vacation outside our native Holland—destination Switzerland. The years immediately after World War II experienced what was perhaps the last—admittedly receding—wave of Alpine travel, before mountain tourism, at least during the summer months, was defeated by the beach.[1] We stayed in a rented chalet in Iseltwald, overlooking Lake Brienz; made daily excursions in the Bernese Oberland to such natural wonders as the Aareschlucht, the Lütschineschlucht, and the Rhône Glacier; and learned to recognize the profiles of the famous mountains in the region, the triple crest of the Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau, and the massive peak of the Finsteraarhorn. My parents, not usually given to unnecessary spending, allowed us to buy souvenirs at every place we visited, in the hope—I gather in retrospect—that we would remember our trip. It worked. Thanks to our Alpine walking canes, covered with stocknageln bought at each site we visited, as well as our Alpine hats, black felt yarmulkes with red trim, covered with pins—miniature metal cowbells, miniature wooden chalets, and plastic Edelweiss—the trip and the names of the places we visited, are still sharply engraved in my brain.[2] The exhibition The Rockies and the Alps at the Newark Museum brought back many of my childhood memories, related not only to the trappings of Alpine tourism, but also to the grandeur of the landscape which made an unforgettable impression on a child used to the Dutch polder landscape.

Of course, the exhibition was not just about the Alps, but also about the Rocky Mountains, two major mountain ranges on either side of the Atlantic, the pictorial renderings of which were presented, according to the museum website, “in dialogue.” The exhibition’s point of departure was the Newark Museum’s impressive collection of American landscape paintings; its novelty was that it presented these canvases in the context of nineteenth-century European mountain painting, showing not only that many American artists working in the Rockies had first learned to paint mountains in the Alps, but also how depicting the Rockies gradually departed from Alpine painting as artists adjusted to a different terrain, travel ethos, and market for their work.

The idea of “dialogue” was graphically presented at the entrance of the exhibition where black and white portraits of the two main representatives of Alps and Rockies painting, Alexandre Calame and Albert Bierstadt, confronted one another (figs. 1, 2). Both portraits were mounted on full-color, wall-sized reproductions of details of their paintings, and each was accompanied by a short quote. The one by Calame seemed intended to convey, in a general way, the nineteenth-century attitude towards mountains: “Nothing elevates the soul as much as the contemplation of these snowy peaks . . . when lost in their immense solitude. Alone with God, one reflects on man’s insignificance and folly.” The one by Bierstadt announced the theme of the exhibition: “The [Rocky] mountains are very fine as seen from the plains. They resemble very much the Bernese Alps.”

As one entered the exhibition, installed in the attractive brand-new exhibition space on the second floor of the Newark Museum, one quickly became aware that it was divided into several modules, each devoted to a specific theme: “Artist-travelers Sketching Outdoors,” “Exploring the West,” “Bierstadt in the Rockies and the Alps,” “Bierstadt and Ludlow,” “The Grand Tour: Artists in Iconic Places,” “Wetterhorn and Lake Lucerne,” “Technology of the Picturesque,” and “Tourism and Conservation: A Delicate Balance.” The first section drew attention to the challenges of painting in high mountain terrain, where the most beautiful spots were often difficult to access. It was made clear that for the most part, the paintings shown in this exhibition were not produced outdoors, but in the studio from memory aided by drawings, watercolors, and/or small oil sketches made on the spot. A work by the New Hampshire painter Benjamin Champney portrays his travel companions, fellow artist John Kensett (left), medical student Fredrick Ainsworth (right), and Champney himself (middle) during a hiking trip to Switzerland (fig. 3). The painting is dated 1851, though their trip took place in 1845, which means that the work itself was based on memory and on-the-spot sketches (120).[3] In the painting, Kensett is making a quick oil sketch while Champney is drawing in a sketchbook. Rather unbelievably both stand and carry their paint boxes and umbrellas on their backs as they do so. Indeed, the only one who is seated and has divested himself from his backpack is Ainsworth, who is writing in a notebook with a quill. In his memoir, Sixty Years’ Memories of Art and Artists, Champney details the physical stamina artists needed for their mountain trips. Hiking in the Mont Blanc massif, he and his companions made a “hard tramp of thirteen hours,” which, he informs us, was not the longest hike they took during their Swiss trip.[4]

The exhibition showed several sketchbooks to demonstrate the visual notations artists made on their travels. It was remarkable how much alike they were—small books with light pencil sketches outlining specific mountain crests or broad panoramic views. Occasionally, drawings of a Swiss peasant in regional dress or a mountain chalet would allude to the human presence in the mountains. A particularly smart aspect of the exhibition was the addition of an iPad featuring a sketchbook by Sanford Robinson Gifford, which allowed viewers to follow Gifford on his journey (fig. 4). In addition to sketchbooks, the exhibition also included some oil sketches, including Frederick Edwin Church’s beautiful Rainbow near Berchtesgaden quickly brushed in oils on paper board (fig. 5).

The second section, “Exploring the West,” began with Bierstadt’s Landscape Study: Estes Park, Colorado, Morning of ca. 1859, based on the artist’s earliest encounters with the Rocky Mountains and depicting a site that, thanks in part to Bierstadt’s paintings, would become known as “America’s Switzerland” (fig. 6). Though born in Germany, Bierstadt had come to America at the age of one, then returned to Germany to study painting in Düsseldorf in 1853–56. In 1856, he went on a sketching trip to Switzerland and Italy, together with Worthington Whittredge (1820–1910), whom he had met in Germany. After returning to America in 1857, he made his mark at the 1858 spring exhibition of the National Academy of Design, where he showed a large painting of Lake Lucerne and the Alps (whereabouts unknown). A year later he traveled out West joining Frederick W. Lander’s survey party of the Rocky Mountains. He returned in the fall, with a trunkful of sketches, photographs, and Native American artifacts. Estes Park shows the extent to which Bierstadt, on his first trip, was still conditioned by the European mountain landscape aesthetic that had been part and parcel of his training in Düsseldorf. His painting resembles a formula often found in the work of Alexandre Calame: a dark foreground is contrasted with a light background of snow-covered mountains and sky separated by a middle ground of water. A dark repoussoir tree connects the three successive layers (see, for example, Calame’s Lake of the Four Cantons in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London).

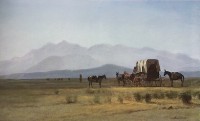

Around the same time that Bierstadt painted Estes Park, he also produced quite different works, such as Surveyor’s Wagon in the Rockies, which shows mountains rising from a low foreground plane—a composition rarely encountered in Europe, in part because it is rarely seen there (fig. 7). Bierstadt initially viewed the West “through the lens of his European experiences,” but soon came to see the unique aesthetic qualities of the Rockies (93).

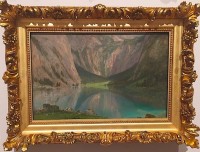

The next two sections both focused on Bierstadt. “Bierstadt in the Rockies and the Alps” further elaborated on the dialogue that exists in the artist’s works between his paintings of European and American scenes, while “Bierstadt and Ludlow” was devoted to the artist’s relationship with his companion on his second trip out West, the young writer Fitz Hugh Ludlow. In 1863, when the two men undertook their trip, Bierstadt was already famous. Ludlow’s role was to make him even more so by writing articles about the trip to be sent to newspapers and magazines. Seven years after the trip and just months before his death at age thirty-four, Ludlow would republish these articles, revised and expanded. A short but fascinating article on Ludlow by James M. Saslow in the exhibition catalogue connects Ludlow’s often ecstatic descriptions of the Western landscape with the writer’s lifelong drug addiction. Saslow makes the point that “the delirious fantasy” in some of the “drug-fueled passages” in Ludlow’s writing seems to be “fulfilled” in some of Bierstadt’s landscapes, such as Western Landscape Mount Whitney (fig. 8). While there is certainly an emotional connection between Ludlow’s prose and Bierstadt’s painting, it is difficult to say whether the ecstatic sentiment they both evoke is nature- or drug-induced (or both). Nature, and especially mountains, do seem to have had the power of provoking forms of ecstasy during the Romantic period, and there are other landscapes in the exhibition, such as Church’s oil sketch Obersee, Germany, July 1868 that at first glance looks like a hallucinogenic vision but that appears to have been inspired by aesthetic rapture instead (fig. 9).

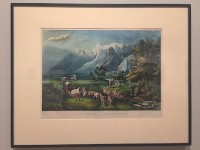

The next two sections “The Grand Tour: Artists in Iconic Places” and “Wetterhorn and Lake Lucerne,” took the viewer back to the Alps and demonstrated that, unlike the still unexplored Rockies, the Alps were well-trodden terrain with tourist sites that were celebrated for their natural beauty. Codified in popular tourist guides, such as Murray’s and Baedeker’s, and marked with one or more stars to indicate their level of attractiveness, these sites became household names among real as well as armchair travelers.[5] This wholesale tourism set the Alps apart from the Rockies, which, until the end of the nineteenth century, were not very accessible to tourists, but were nonetheless popular in the imagination. It was a popularity on which publishers like Currier and Yves banked by producing lithographs such as The Rocky Mountains: Emigrant Crossing the Plains (1866) by British-born Francis Flora Bond Palmer, one of whose specialties was Western landscapes (fig. 10). Since Palmer never traveled out West, these prints must have been based on sketches and paintings by other artists or on photographs.

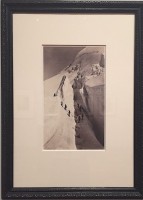

As the exhibition demonstrated in the next section, “Technology of the Picturesque,” the growing interest in mountain travel and the developing medium of photography were closely connected. Photography was used both for documentation and as a means to popularize the Alps and the Rockies. As an example of documentation, the exhibition showed the dramatic photograph Ascent of Mont Blanc by Auguste-Rosalie Bisson, recording an expedition scaling Mont Blanc in 1861 (fig. 11). The photograph strikingly demonstrates the challenges and dangers of the new “sport” of “Alpinism,” popular since the 1850s. Though mountain climbing was practiced both in the Alps and the Rockies, the Alps were famous for challenging climbs, including Mont Blanc, the Wetterhorn, the Eiger, and especially the Matterhorn or Mont Cervin, which was not “conquered” until 1865 (79–83). In Bisson’s photograph, we see mountaineers trying to cross a crevasse, a deep fissure in the glacier surface of the mountain.

As an example of the use of photography to popularize mountains, the exhibition included a magic lantern show, with a real magic lantern that digitally projected a group of lantern slides of famous mountain peaks as well as Swiss peasants in local dress (fig. 12). The original lantern slides could be seen as well, against a light table mounted on the wall (fig. 13). The exhibition also included a stereoscope that visitors could pick up to look at several stereoscopic photographs (fig. 14). And it demonstrated how photographs were transformed into popular prints and picture postcards.

The final section of the exhibition focused on mountains and conservation and ended with a large board on which visitors could post notes to answer the question “Do mountains still matter”? (fig. 15). The responses were mostly of very young visitors, who seemed almost unanimous in the opinion that they did. Juliana answered emphatically with a big “yes” inscribed over two smiling, lip-smacking mountain heads.

“Do mountains still matter?” Without attempting to answer that rather big question, I do want to note that, apparently, they matter to museums. In 2018 there were several other exhibitions devoted to mountains. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, early in 2018, hosted an exhibition called Diamond Mountains: Travel and Nostalgia in Korean Art, featuring some thirty works depicting the famed and culturally important mountain range on the border of the two Koreas (https://www.metmuseum.org/). The China Institute in New York presented Art of the Mountain: Through the Chinese Photographer’s Lens, a year-long exhibition of contemporary Chinese mountain photography (https://www.chinainstitute.org/). And, the Kunstmuseum in Winterthur, Switzerland mounted an exhibition with the oxymoronic title Dutch Mountains, which was devoted to mountain landscapes by Dutch seventeenth-century artists Jacob van Ruisdael and Allaert van Everdingen (https://www.kmw.ch/), both of whom were drawn to mountains as an alternative to the Dutch landscape in which they grew up.

The Rockies and the Alps exhibition was accompanied by a handsome catalogue with four essays, two by co-curators Katherine Manthorne (CUNY) and Tricia Laughlin Bloom (Curator of American Art, Newark Museum), and two by Patricia Mainardi and James M. Saslow, both faculty emeriti at CUNY.

Manthorne’s essay largely follows the outline of the exhibition and deals with its overriding theme, the “struggle [of American artists] to reconcile the hallowed European traditions with the specificity of Rocky Mountain geology, flora, and fauna [she might have added, ethnography] to present a distinct American reality” (90). While dealing specifically with several of the central themes of the exhibition, she also adds some that are only tangentially presented, like the encounters with native people in the West and the role of women in exploring the region, representing it in paintings and literature, and popularizing it, as in the case of Flora Bond Palmer.

Museum curator Tricia Laughlin Bloom focuses on the history of the Newark Museum’s collection of American landscape paintings. She points to the intersection of the histories of that collection and the museum’s natural science holdings. Using the Newark Museum collections as a case study, her essay demonstrates how the nineteenth-century fascination with nature (and, perhaps, mountains in particular) was intimately linked to religion and the aesthetic, as well as the scientific. Tourists, including artists, while enraptured before the beauty of nature, which reminded them of the infinite power of God, were also keenly focused on its physical properties and habitat. On their mountain travels they collected rock specimens, plants (which were dried and put in herbaria), and even small animal specimens, such as birds and eggs. These were the final days of the concept of the “book of nature,” and the belief, best formulated by Galileo, that “ . . . God is known first through Nature, and then again, more particularly, by doctrine; by Nature in His works, and by doctrine in His revealed word.”[6] Like the bible, the book of nature had to be read carefully, leaving no stone unturned as it was understood that its holistic grandeur was composed of an infinite number of wondrous parts.

Patricia Mainardi in her essay “Julie to Frankenstein to Heidi: The Alps in the European Imagination” relates the fascination with the Alps to late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literature, which, like Alpine painting during the same period, reflects the gradually changing attitudes towards mountains and the Alps in particular. Moving from Jean-Jacques Rousseau to Johanna Spyri, she shows how the Alps could inspire awe, terror, elation, or a sense of wholesomeness, each to a different degree depending on the period and the individual.

The final essay, “Nature, God, and Hashish,” by James Saslow, also makes the link between art and literature, specifically between Bierstadt and his ‘publicist’ Fitz Hugh Ludlow. Saslow relates Ludlow’s The Heart of the Continent (1870), a book based on his travels with Bierstadt to the Rocky Mountains in 1863, to the author’s earlier publication, The Hasheesh Eater (1857), which was something of a succès de scandale in its time. He points out the extent to which the descriptions of his reactions to landscape sites in the second book resemble Ludlow’s account of drug-induced states in the first book, which graphically details the “altered perceptions of space and time, of light and water, and the symbolic associations they provoked in his mind” (155). Saslow is right, of course, in emphasizing the importance of rapture to nineteenth-century Romantics, to whom ecstasy was the antidote to ennui. Drugs, nature, religion, and sex were ever so many avenues along which ecstasy could be achieved.

All in all, The Rockies and the Alps was a modest-sized but big ideas exhibition, organized by a curatorial team that thought long and hard about ways to capitalize on the strengths of a specific museum collection, in this case that of the Newark Museum. In so doing, they produced a show of an international scope that also, in interesting ways, reflected the history of the museum in which it was held. Indeed, John Cotton Dana, the founder of the Newark Museum, a man who is seen by many as one of America’s great museum curators, would have been proud of this exhibition. While firmly rooted in the museum’s history, The Rockies and the Alps is also forward looking, especially for the cross-disciplinary connections it makes between nature, art, science, religion, tourism, the environment, and human emotional needs.

Petra ten-Doesschate Chu

Seton Hall University

petra.chu[at]shu.edu

[1] The post-war attraction of Switzerland may also have been related to the fact that, unlike most other European countries, Switzerland, neutral in World War II, had not suffered the kind of destruction other European countries had. Indeed, from the same trip I remember driving through Frankfurt, then a city still largely in ruins.

[2] Stocknageln are tin or aluminum souvenir badges that are nailed to a hiking stick.

[3] The exhibition catalogue reproduces a pencil and watercolor drawing by Kensett of a Standing Artist (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC), which may have served Champney in the painting of his self-portrait. The use of a friend’s drawing is uncommon, though it may be less so than we generally assume.

[4] Benjamin Champney, Sixty Years’ Memories of Art and Artists (Woburn, MA, 1900), 62. On-line access is available at https://archive.org/.

[5] Baedeker’s guide to Switzerland was first published in 1844. It was the best-selling Baedeker guide ever. It ran into dozens of German editions and was translated into French as well as English.

[6] Galileo’s letter to Christina, the Grand-Duchess of Tuscany, was written in 1611 and rewritten in an expanded version in 1615. It set out Galileo’s views on the relation between science and religion. The letter was initially circulated in handwritten copies and was not published until 1636 (Strasbourg). It has become a classic text, reprinted thousands of times and translated into hundreds of languages. For an on-line version, see, among many, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/.