Goya’s Graphic Imagination

Reviewed by Reva WolfReva Wolf

Professor of Art History

State University of New York at New Paltz

wolfr[at]newpaltz.edu

Citation: Reva Wolf, exhibition review of Goya’s Graphic Imagination, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 20, no. 3 (Autumn 2021), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2021.20.3.28.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Goya’s Graphic Imagination

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

February 12–May 2, 2021

Catalogue:

Mark McDonald, with contributions by Mercedes Cerón-Peña, Francisco J. R. Chaparro, and Jesusa Vega,

Goya’s Graphic Imagination.

New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Distributed by Yale University Press, 2021.

320 pp.; 166 color illus.; chronology; notes; bibliography; index.

$50.00 (hardcover)

ISBN–978–1–58839–714–0

He stares directly at us, intensely, and worried, as is communicated through the positioning of his irises, each centered in the middle of the eye, touching the upper eyelid but not the lower, and through his peaked eyebrows. These are the eyes of Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) in a self-portrait drawing from the mid-1790s (fig. 1). Diminutive in size, at 6 by 3 5/8 inches, yet enormous in scale and emotion, it could serve as an emblem for Goya’s Graphic Imagination, a compact yet potent exhibition of the artist’s prints and drawings on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Spring 2021. The exhibition contained around a hundred works, occupying three relatively intimate rooms of the museum typically reserved for exhibitions of works on paper, and spilling into the adjacent hallway. It is entirely fitting that Goya’s self-portrait had pride of place in the exhibition, isolated on a pedestal and greeting us as we approach the space (fig. 2). In addition to echoing the spirit and scale of the exhibition, organized thoughtfully and insightfully by Mark McDonald, curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, it embodies some of the key interrelated themes explored throughout the chronologically arranged display: the human likeness to other animals, suggested in the self-portrait by Goya’s unruly hair, which circles his face like a mane; and human foible, implied by the medal he wears, with his name written upside-down, as if to be a gesture of self-criticism of his own vanity.

Within the chronological scheme of the exhibition, the first room begins with early works, from the 1770s, then moving on to drawings and prints of the 1790s, when the artist’s etching and aquatint series, the Caprichos, was published; the second room focuses on the first decades of the nineteenth century, and the final room, Goya’s last works of the late 1810s and 1820s. Drawings are interspersed with prints, encouraging viewers to discover the interconnections between them. The layout inspires close looking, inviting us to see what is there to see.

Goya’s Prints: Exhibition Challenges

Regarding the print series, there is no ideal way to show them on the walls of a museum. Goya conceived of most of these series—certainly the Caprichos (1799) and Tauromaquia (1816), and probably also the posthumously-published Disasters of War (ca. 1808–15; published in 1863) and Disparates or Proverbios (ca. 1815–19; published in 1864)—as what we now call artist books.[1] The Caprichos and Tauromaquia both were advertised by the artist in the Madrid newspapers as available for purchase in complete sets. The prints are numbered in sequences—distinct from the order in which the prints were made—to bring out specific associations and relationships between word and image, such as in the sequence of “ass” satires in plates 37 to 42 of the Caprichos, or the progressive ordering of captions to underline messages already apparent in the imagery in plates 21 to 23 of the Disasters of War: It Will Be the Same (Será lo mismo), All This and More (Tanto y mas), The Same Elsewhere (Lo mismo en otras partes). The complexity and richness of these associations and relationships depend upon us viewing the entire series in sequence. A sequence as experienced in a book, as we move from page to page in an intimate physical relationship with the prints, is different from a sequence viewed hanging on the wall, mounted and framed. Moreover, when the work in question is extensive—in the Caprichos, for example, there are eighty prints—they will occupy quite a bit of gallery real estate if hung in a row. It would be a considerable challenge to effectively display all Goya’s series in their entirety. One common approach, arranging them in double rows, compromises the sequencing. Moreover, the sheer volume of prints would make it impossible for viewers to take it all in, and to give each print its due.

In the past decade, curators have explored diverse methods for dealing with such challenges. Two examples will suffice to give an idea of the range of approaches that have been deployed in presenting Goya’s prints. Several groupings of prints were included in Goya: Order and Disorder, a large theme-based show of work in all mediums held at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 2014–15. Works on paper were clustered in groups and intermixed with paintings. For instance, a selection of twelve prints from the Disasters of War were grouped in three rows of four, which gave a sense of the full potency of the series but lessened our ability to look closely at each work, while another print from the same series, plate 22, All This and More (Tanto y mas), showing a pile of bodies, was placed suggestively next to a still life of a pile of fish (fig. 3).[2]

The second example, highlighting the wide expanse of Goya’s work as a printmaker, was the exhibition, also of 2014–15, Goya: A Lifetime of Graphic Invention, held at the Meadows Museum at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. Unique in this exhibition was the decision to display the Caprichos, Disasters of War, Tauromaquia, and Disparates not in the order Goya arranged them, but in groupings intended to reveal in new ways the myriad associations the print series contain. For instance, pairings of Caprichos nos. 11 and 76, 55 and 26, and 33 and 40 accentuate the ridicule of illicit behavior in men, perceptions of vanity in women, and quack medicine, respectively (fig. 4).[3] These two distinct approaches suffice to give a sense of the limitless possible ways of exhibiting Goya’s prints. Unfortunately, the one way they cannot be presented in a museum is as Goya intended them (at least in the case of the works he published, the Caprichos and Tauromaquia), as books that we handle.

For Goya’s Graphic Imagination, to his credit the curator chose to feature a small selection of prints from each series in order to amplify, in impressively lucid ways, some of the remarkable details within the prints—the kinds of details that might easily go unnoticed in a larger-scale presentation. The wall labels, which contain largely the information and insights in the accompanying catalogue, serve the purpose well. A case in point is the discussion of a working proof for plate 31 of the Tauromaquia, Banderillas with Firecrackers (Banderillas de fuego; fig. 5), which pulls us in and opens our eyes:

From 1808 on, bullfight advertisements announced a new, less bloody method of harassment that used firecrackers on banderillas (barbed darts). . . . Goya draws the viewer’s eye to the firecracker-laden darts in the bull’s neck by positioning them in the lightest part of the print. One of the most striking details in his entire graphic body of work, this area seems to smolder; it was created with burnished aquatint, which produced a stain of uneven dark borders suggesting a smoking explosive device (222).

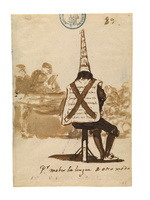

This description calls attention to an intriguing technique-content equivalency, an aspect of Goya’s work that merits further study and seems to be present in other works in the exhibition. In For Speaking in a Different Way (Por mober la lengua de otro modo), picturing a seated figure being sentenced by the Inquisition, lines moving down the legs and stains of ink puddling beneath them seem to be equated with blood, as the curator observed (fig. 6).[4] This equation of ink stained into the paper with blood is also suggested in a third work in the exhibition, Prisoners in Irons, in which the clothing looks soaked, and the shadow on the ground again brings to mind pooling of blood; the catalogue entry for this drawing hints at the possibility, concluding that the figures are “shackled over a stain of pitch-black shadow” (194).[5]

The attention to meaningful details was to the benefit even of scholars who have studied Goya’s work for decades. I saw things I had never before noticed. Still, one reviewer of the exhibition, Jason Farago, writing for the New York Times, proposed, in discussing the size of the exhibition, that Goya’s Graphic Imagination is “geared to beginners,” adding, “[m]e, I’d take a larger show, with the full run of the ‘Caprichos’ and the ‘Disasters.’”[6] But exhibition size and audience level are entirely distinct issues. And, when it comes to the work of certain artists, Goya included, perhaps we are all always “beginners.” Goya’s Graphic Imagination is proof that a sharp focus on a carefully selected group of works can teach us at least as much, if not more, than an exhaustive show containing all the works in Goya’s print series.

The exhibition was designed to share insights gained through close looking, but also to prod us to look on our own by providing good models for how to do it. The concluding sentence of the introductory wall text, positioned next to the 1790s self-portrait, is a direct statement of the aim to encourage close looking, setting a tone that is echoed in descriptions of individual works such as Banderillas with Firecrackers: “Through looking to arrive at seeing, the viewer draws closer to understanding Goya’s astonishing creative process” (fig. 2).

Prints and/with Drawings

Another way the exhibition foregrounds Goya’s creative process is by placing side-by-side prints and their related drawings, building upon the existing body of literature on the relationships between Goya’s works in these two mediums.[7] Connections between prints and drawings is a special interest of the curator of Goya’s Graphic Imagination. Previously, McDonald organized and wrote the extensive catalogue for Renaissance to Goya: Prints and Drawings from Spain, an exhibition held in 2012 at the British Museum, where at the time he was curator of Old Master Prints and Drawings. In his introduction to the section of the catalogue on Goya, McDonald commented, “Goya’s prints and drawings worked together and are discussed here chronologically.”[8] This is the same vision and approach that we see in Goya’s Graphic Imagination. In 2015, McDonald contributed an essay, “Goya’s Prints among his Drawings,” to the catalogue accompanying Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album, held at the Courtauld Gallery, focusing on a particular group of Goya’s works. He explained in this publication that prints and drawings “were complementary parts of a single visual language” and that their “cross-fertilization was at the heart of Goya’s graphic art.”[9] In an interview with McDonald about Goya’s Graphic Imagination, posted on the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he stated that it is “crucial” to consider these works together “because they are so intertwined,” observing: “While it is far easier to speak about works in clear categories, I found that there is so much overlap and that it is impossible to extricate Goya’s prints from his drawings. His themes intersect and interweave. Goya thought on paper through his prints and drawings.”[10] It could be argued that the intersections and interweavings extend to Goya’s painted work, especially since his early paintings that were designs for tapestries are, like most of the later prints and drawings, works in series and thematic groupings. Yet the small scale of the prints and drawings, the interplay of word and image in many of them, and their status as non-commissioned works, give them a special bond. Also, we can witness Goya’s working processes by comparing prints to drawings, and we are led to several such comparisons in Goya’s Graphic Imagination through careful installation choices.

A drawing on loan from the Prado Museum, related to Goya’s most famous print, The Sleep/Dream of Reason Produces Monsters (El sueño de la razon produce monstruos), plate 43 of the Caprichos, was hung directly next to the print. In the drawing, a jumble of multiple human faces, and, at top, the head and front legs of a horse, emerge from the mind of the artist, as conveyed by the lines emanating from around his head. All these elements are removed in the print to allow the winged creatures of the night, less pronounced in the drawing, to come forward, at the same time producing a tighter, less busy composition.

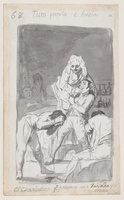

In a second example from the Caprichos, plate 33, To the Count Palatine (Al Conde Palatino), once again a tighter composition, with fewer elements, is presented in the print than in the related drawing, from Album B, page 68, Every Word Is a Lie (this caption written in imperfect Italian, as Tuto parola e busia) (figs. 7, 8). In the exhibition catalogue, two distinct interpretations of the subject of these works are offered. In the catalogue entry on the drawing, by McDonald, it is described as depicting a quack dentist yanking out a tooth; two figures in the foreground, having likely just endured the same procedure, are sickened, one clearly vomiting (88). The catalogue entry on the print, on the other hand, by Mercedes Cerón-Peña, proposes that this sickened individual may have been a victim of an experimental treatment of venereal disease that resulted in vomiting—and worse (114). This latter interpretation is interesting, and would be strengthened if accompanied by an explanation for why tooth extraction would be included in such a scenario. In any event, the wall labels in the exhibition, placed side-by-side, also offer both interpretations. It is an appealing strategy to present multiple plausible interpretations; at the same time, explicitly acknowledging this strategy would have provided a desirable clarity. Turning now to the compositions, in the drawing, the Count Palatine is standing on something (unidentifiable) and bends down to reach into the mouth of the figure standing in front of him whose tooth he apparently is extracting. In the print, he remains standing above and behind his patient, but he no longer is bending, his torso now straightened and his bent knee now absent entirely, as is the object that was supporting him. It is as if the quack has no legs and is levitating or supported by his patient: a magician whose tricks rely on those who are willing to be deceived.

In the matter of interpretation, Goya’s prints and drawings present fascinating challenges. He seems to have aimed to produce multiple meanings and associations within both individual works and serial groupings, but sometimes it is clear that he created concrete, specific meanings and associations. Therefore, it is a good idea to avoid a formulaic approach in trying to decode his work. An exciting aspect of the history of interpreting Goya’s art, reminding us that art history really is a collaborative activity, is that the insights of one scholar can open new doors to another, who arrives with fresh ideas and different perspectives. The very language we use can promote new research. In the wall label and catalogue entry discussions of drawings such as Construction and A Disheveled Woman with a Group of Figures, both from Album F, we are led to rethink how to understand them: in the first instance, it is proposed that the building in the background “might be the Madrid Opera House or the column in Buen Retiro Park,” both under construction in the late 1810s, and “might relate to the one [a drawing in Album F] preceding it” and in this context “perhaps . . . refers to rebuilding a democratic system through common endeavor” (all emphases mine); in the second case, again a mystery building is present, with “a distinctive dome flanked by a tower” which “suggests a specific form of architecture, but what does it represent?” (184, 192). The very posing of this question may lead, eventually, to a convincing answer. (Is it a mosque?)

Allusions to specific works of literature and to events of history and of Goya’s time have been convincingly ascribed to Goya’s prints and drawings and are especially fruitful avenues to interpretation, as is the consultation of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century dictionaries to consider the multiple meanings of words that he used in captions or that concern what he depicted. In the area of literature, an important path was paved in the work produced by Edith Helman in the 1950s and 1960s and later by Nigel Glendinning. Glendinning’s interesting discovery of Goya’s likely allusions, within the symbolic prints of the Disasters of War, to a satirical work by the Italian poet Giovanni Battista Casti, Gli animali parlanti (1802; Spanish translation, 1813), is given ample attention in the exhibition catalogue, serving in a way as the example of how Goya “drew inspiration from literature” (40).[11] This emphasis makes sense up to a point, since the work fits well with the theme of human associations with other animals that the exhibit invites us to consider, yet Helman’s earlier contributions, for example, are barely mentioned.[12] The by now vast scholarship on Goya makes it impossible to cover everything. Still, the mention of literary references and subjects in Goya’s art might have received a slightly more representative presentation.

Looking at the Drawings

The drawings, like the prints, have their own contexts as series. While comparing them to the prints provides valuable insight into Goya’s working processes, it also removes them from those contexts. The drawings have complex histories and seem to have been largely private, perhaps viewed among friends in intimate settings. Yet, there is some evidence that the existence of drawings by Goya conceived as works of art was not entirely a secret during his lifetime. A letter published in a short-lived Madrid daily, El conservador, a pro-constitutional paper with a brief existence during a time of great political upheaval, proposed that the municipality of Madrid commission Goya to draw or paint what he saw at the offices of the Inquisition, disbanded at the time, 1820 (only to be reinstated in 1823), “to serve as a permanent documentary record of fact” (“ad perpetuam rei memoriam”).[13] The mention of drawing is a tantalizing detail, especially given that, around this time, Goya made several drawings of Inquisition subjects (fig. 6, for example).[14]

Goya produced many of his drawings in specific groupings, referred to variously as “albums,” “sketchbooks,” “books,” “private albums,” or “journal albums.” McDonald assesses the significance of these distinct terms in his essay for the catalogue of Goya’s Graphic Imagination, noting that he favors, given the personal nature of the work, the term “journal,” which was proposed by Eleanor Sayre, the mid-twentieth-century curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, who had a special expertise in Goya’s works on paper and did some significant groundwork in helping us understand the groupings of Goya’s drawings—groundwork that was later built upon by other scholars, among the most notable, Pierre Gassier and Juliet Wilson-Bareau (15).[15] The task is being taken up currently by a team of researchers at the Prado Museum under the direction of José Manuel Matilla and Manuela B. Mena Marqués.[16] The very terms we use to describe these groups of drawings, as McDonald perceptively notes, have implications for how we interpret them and can influence the questions we ask about them. If they are “private albums,” might their secret nature be related somehow to Goya’s likely involvement in Freemasonry?[17] While McDonald favors “journal,” he continues to use “album” in both the exhibition and catalogue, as the more familiar term found in most publications on Goya, a reasonable choice. How do we decide when to stay with a given nomenclature and when to deviate for the sake of precision or interpretation? “Sketchbook” (cuaderno) was used in the catalogue of a recent, and in many ways spectacular, expansive exhibition of Goya’s drawings held at the Prado Museum, perhaps to link the practices of Goya to his forebears and contemporaries.[18] Goya’s sets of drawings, however (aside from a sketchbook he started around 1770, known as the Italian Notebook) are worked and reworked, with captions often added after the drawings, sometimes in a different medium, giving us a sense, as McDonald astutely noted in a review of the Prado Museum show, that Goya understood them as finished works, not “sketches.”[19]

Another significant issue of terminology, with implications for interpretation, concerns how we classify each of the known eight groups of drawings. McDonald informatively calls attention to this issue as well, making note, briefly, of how in the mid-nineteenth century the groups of drawings were divided up for sale, making their reconstruction a challenge and our knowledge of how Goya grouped them, difficult, if not impossible, to ascertain. Eleanor Sayre made significant headway in this direction in discerning eight distinct groupings, which she placed in chronological order based on style (their chronology being another challenge with which we are still grappling). She classified them in a non-descriptive way, alphabetically, according to the chronology she devised, beginning with “Album A” and concluding with “Album H.”[20] This classification was helpful, just in allowing us to get a basic handle on the drawings, and continues to be used even though aspects of Sayre’s chronology have been questioned over the years by several scholars: no consensus exists today on the dates of most the albums.[21] This question then arises: do we change how we classify them since the chronological progression implied by the alphabetical sequence of “A” through “H” is no longer accepted? Taking up the question, Juliet Wilson-Bareau proposed switching the alphabetical designations with names that capture the spirit of each drawing group.[22] The idea is appealing, yet its execution creates new problems, as McDonald observes:

While the descriptive titles given to the albums broadly convey their subjects, categorizing them in this way implies a conceptual point of origin, presuming that Goya set out to create coherent series of images, which is not the case. His drawing practice was ongoing and nuanced—unconstricted. The drawings reveal varied ambitions. The Inquisition Album, for example, includes numerous drawings of subjects completely unrelated to the Inquisition (16).

It’s not entirely clear, then, why McDonald opted, in the exhibition catalogue, to use the heading “The Inquisition and Images of Spain Albums,” for example, in his discussions of Album C and Album F, respectively (168). This choice sustains the very problem he diagnoses. However, on the walls of the museum, he sometimes underplayed and qualified the problematic names of the groupings, such as in the wall label for Albums C and F, despite its heading, “Reflecting Spain”:

Shown here is a group of drawings that Goya produced mainly during the second decade of the nineteenth century in two albums (known as C and F). They reveal a staggering range of subjects, testifying to the artist’s ongoing commitment to drawing as a principal means of expression.

One of the longest and most complex of Goya’s compilations of drawings, Album C comprises 125 known drawings of great diversity, suggesting that he added to it over a long period of time and did not begin it as a cohesive project. The compilation has been called the Inquisition Album, because its most common theme is the abuses of the Spanish tribunal for upholding religious orthodoxy, but it also features images of visions, allegories, religious subjects, and the repercussions of human behavior.

The drawings in that album overlap chronologically, thematically, and technically with those in the so-called Images of Spain Album (F). Close to a hundred sheets treat a range of subjects that relate mainly to human behavior rather than supernatural or esoteric themes. Like Album C, the compilation’s visual variety suggests that Goya did not conceive it as a single project with defined content.

Various factors come into play, no doubt, that affect decisions on which terminology to embrace and which to omit. The recent Prado Museum exhibition of Goya’s drawings and the accompanying catalogue avoided using Wilson-Bareau’s nomenclature, choosing instead the “A” through “H” classification system initiated by Sayre. While imperfect, Sayre’s classification system is beneficial in not imposing titles and subjects that Goya did not devise. It has the additional advantage of having been used in the scholarship on Goya since the late 1950s, providing a clear point of reference for researchers. Perhaps the best approach moving forward is to continue with it.

Invitations to Look

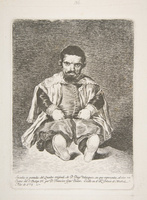

In large exhibitions, we might be easily tempted to skip over Goya’s earliest etchings, based on paintings by his renowned seventeenth-century forebear, Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), assuming they are, as copies, less worthy of close looking than works of his own compositional devising. In Goya’s Graphic Imagination, with no impetus to rush past his first attempts at printmaking, it became startlingly clear that Goya had achieved a technical mastery as a printmaker already at this relatively early stage in his career. A stand-out among the four prints after Velázquez included in the exhibition is El Primo of 1778 (fig. 9). The wall label reminds us that even copying the work of others involves interpretation (not unlike the practice of translation from one language into another):

Goya accentuates the intensity of the man’s gaze; the dark background created by a dense network of lines serves to project his figure toward the viewer. Here, El Primo appears altogether more assertive, even confrontational—subtle differences intentionally introduced by Goya that make his interpretation distinct.

Indeed, the eyes in this print, and especially the positioning of the irises, are curiously similar to those in Goya’s self-portrait drawing of the mid 1790s (fig. 1). In the self-portrait, with his upside-down medallion, is he equating his role as portrait painter to the king to that of court jester? In the caption to El Primo, Goya calls himself a painter (pintor), not a printmaker (grabador), a distinction of rank, it would seem, that he would carry over to his print series, beginning with the Caprichos, in which in the self-portrait that opens the set he identifies himself as “pintor.”

While the exhibition was laid out chronologically—El Primo was positioned on the first wall of the first room—thematic threads were woven throughout, as already suggested. For example, the human associations with other animals that is brought to mind in the self-portrait drawing (fig. 1), is introduced in the second of the three main rooms of the exhibition, in which the Tauromaquia is located, along with prints of and drawings related to the Disasters of War and to some of Goya’s album drawings. The heading accompanying the wall text about the Tauromaquia is “Man against Beast.” This is a topic that later artists would elaborate and that weighs on our minds today. A forthcoming show, scheduled to open in early 2022 at the Royal Academy, London, has the title Francis Bacon: Man and Beast. Here, too, we are brought back to the question of terminology and its implications. What if “Man” and “Beast” were replaced by “Humans” and “Other Animals”?

Another thread present in Goya’s Graphic Imagination if not emphasized in the wall labels was picked up by a few previous reviewers of the show, who, with the January 6, 2021, assault on the US Capitol fresh in their minds, associated it with Goya’s reflections on the presence and dangers of the “populacho”—the mob. In his review, Christian Viveros-Fauné associated the Spanish term with Abraham Lincoln’s “mobocracy,” writing:

Goya’s representations of the “populacho” constitute the flip side of his decades-long obsession with rationalism—the engine that drives, among other works on view at this exhibition, the satirical print series Los Caprichos (1796–98). These exist not as meditations on the uses and abuses of Enlightenment liberalism (whose present-day counterpart we might identify as a belief in science or expertise or legacy media or cosmopolitan multiculturalism), but as allegories of his time’s xenophobic and bloody popular clapback against reason. . . . Then, as now, the rabble rarely countenances the humanitarian ideals of the elites. In times of great tumult and confusion huge chasms open up between popular and privileged cultures, which can lead to civil strife, war, genocide, or worse (there is always worse).[23]

Likewise, Linda Yablonsky’s review foregrounded the parallels with our own time: “With the Capitol insurrection so recent in our experience, there can’t be a better time to reckon with Goya than now.”[24] Goya’s exploration of the “mob” is not, in fact, a theme featured in the exhibit, but it is referred to in the wall label accompanying the print Spanish Entertainment, one of the four lithographs from the Bulls of Bordeaux, made in 1825, when Goya was exiled in Bordeaux, where he lived out the final years of his life: “Made for French audiences, Spanish Entertainment hints at a Romantic identification of bullfighting with Spain. Yet, as the work of an artist living in semi-exile because of the political situation at home, it may also reflect his disillusionment with the masses, presented here as an irrational crowd.”[25]

The word “graphic” in Goya’s Graphic Imagination has a double meaning. In his introductory essay for the catalogue, also titled “Goya’s Graphic Imagination,” McDonald outlines the following topics (which overlap with but do not exactly match the thematic headings included in the exhibition): Dreams and Disorientation; Violence; Madness; the Five Senses; Reading Goya (about interpretation); and, Truth to Life. McDonald’s essay concludes with a reminder that the romantic myth of Goya as a “solitary genius” is just that. The point makes a perfect transition to the other introductory essay in the catalogue, “Goya in Context,” by the art historian Jesusa Vega. Vega’s essay offers a contextual framework for Goya’s modern perspective on the world with its useful overview of the various forward-looking Spanish organizations founded in the eighteenth century, the “sociability” of the age, attitudes towards women, and the importance of particular locations, such as the cosmopolitan port city of Cádiz.

The introductory essays by McDonald and Vega are followed by succinct catalogue entries on the individual works by McDonald, Mercedes Cerón-Peña, and Francisco J. R. Chaparro, each accompanied by a full-page, high-quality image. This part of the handsomely designed catalogue is divided into chronological and series-based sections, each with its own introduction. A few highlights are: interesting details of provenance unique to particular impressions, such as the American painter John Singer Sargent’s ownership of plate 1 of the Caprichos, a self-portrait; the special relevance of plate 30 of the Disasters of War to Pablo Picasso’s composition of Guernica (1937); and, the discussion of the disturbing drawing known as A Woman Attacking a Sleeping Man, from Album F, which “manifests Goya’s unique ability to suggest sequence by indirectly condensing time” by showing the man, already wounded and about to be attacked again with an axe that, as the two pieces of wood in the foreground imply, he had been using previously himself (102, 146, 200).

Most of the works in the exhibition are from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s superb collection. These were enhanced by select drawings and print proofs from the Prado Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and some private collections. Four unique works from the Biblioteca Nacional de España that are in the catalogue did not make it to the show; this lending partner dropped out when it had to be rescheduled from Fall 2020 to Spring 2021 due to the closure of the museum during Covid (76–77, 132–33, 134–35, 224–25). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, working deftly under uniquely difficult circumstances, replaced the BNE works with items from its own collection, such as the striking El Primo (fig. 9), a print that for me was a highlight of the show; this switch was perhaps a blessing in disguise. In any event, the focus on works in the Museum’s collection, and the manageable size of the exhibition, together constitute an excellent model for special exhibitions. It is a model allowing for research that enhances knowledge of the collection, the production of an exhibition that can be readily absorbed by viewers, and, on a practical level, is unwasteful of all kinds of precious resources.

A special place in Goya’s Graphic Imagination was afforded to the print known as the Colossus, positioned in the middle room of the exhibition on a pedestal and directly behind the mid-1790s self-portrait, also, as already noted, set off by being placed on a pedestal. The arrangement created a dialogue between the two works (fig. 2) that served multiple purposes—among them, to sum up the focus of the exhibition on prints and drawings. This is also a unique case in which a painting by Goya is brought into the discussion, both in the exhibition and in the catalogue (the catalogue entry is around twice the length of the others, 164–67). The attribution of the painting, which is in the collection of the Prado Museum, and which, like the print, is known as the Colossus, has been questioned. The occasion of Goya’s Graphic Imagination was used to re-open the question—itself a reasonable task—by comparing the print to the painting. Yet does this discussion belong in an exhibition in which the stated purpose is to explore the connections between Goya’s prints and drawings? However, the suggestive placement of the Colossus in dialogue with the small-sized but giant-scaled self-portrait was compelling. While perhaps unwittingly tied to the longstanding romantic vision of Goya as an isolated genius that the words of the catalogue aim to dispel, this placement presents the idea that Goya himself was, like the colossus he portrayed, a “lonely giant,” this being the inevitable destiny of anyone willing and able to observe the follies of humanity and to convey them through unflinching and engrossing creations. Goya’s Graphic Imagination invites us to see how Goya shows us who we are. In this respect, and many others, the exhibition was a resounding success.

Acknowledgments

With gratitude to Eugene Heath, who offered numerous valuable editorial suggestions, and who made possible my visits to the exhibition during Covid, sharing useful insights along the way.Notes

[1] On Goya’s Caprichos as among the precursors to today’s artist book, see Bibiana Crespo-Martín, “El Libro de Artista de ayer a hoy: seis ancestros del Libro de Artista contemporáneo. Primeras aproximaciones y precedentes inmediatos,” Arte, Individuo y Sociedad 26, no. 2 (2014): 215–32.

[2] This comparison also was featured in the catalogue; see Janis A. Tomlinson, “War,” in Goya: Order and Disorder, by Stephanie Loeb Stepanek, Frederick Ilchman, and Janis A. Tomlinson, exh. cat. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2014), 284–85.

[3] As the curator, Alexandra Letvin, explained: “By hanging the 228 prints not in their published order, but in thematic groupings, I emphasized Goya’s graphic work as a locus of experimentation and encouraged visitors to discover the multiple interpretations that his prints accommodate.” Alexandra Letvin, “Curatorial Projects,” accessed October 3, 2021, https://www.alexandraletvin.com/.

[4] Mark McDonald, comment to the author at the exhibition, May 1, 2021.

[5] Another example, not in the exhibition, is Estropiada codiciosa (translated alternately as Wounded Greedy Woman or Covetous Old Hag); see Reva Wolf, “Folly, Magic and Music in Goya’s Album D,” in Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album, ed. Juliet Wilson-Bareau and Stephanie Buck, exh. cat. (London: Courtauld Gallery in association with Paul Holberton Publishing, 2015), 46–47.

[6] Jason Farago, “Goya: The Dreams, The Visions, the Nightmares,” New York Times, February 11, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/.

[7] A notable previous exhibition and catalogue to explore these connections was Eleanor A. Sayre, The Changing Image: Prints by Francisco Goya, exh. cat. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1974).

[8] Mark P. McDonald, Renaissance to Goya: Prints and Drawings from Spain (London: British Museum Press; Burlington, VT: Lund Humphries, 2012), 235.

[9] Mark McDonald, “Goya’s Prints among his Drawings,” in Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album, 32.

[10] Rachel High, “Fragments of Dreams: Mark McDonald on Goya’s Graphic Imagination,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Blog, March 26, 2021, https://www.metmuseum.org/.

[11] Other references to Casti in the catalogue are in Jesusa Vega’s essay, “Goya in Context,” 56–57, and Francisco J. R. Chaparro’s catalogue entry for He Defends Himself Well, Disasters of War, plate 78, 158 (cat. no. 45). On the case for Goya drawing upon Casti’s verses, see Nigel Glendinning, “A Solution to the Enigma of Goya’s ‘Emphatic Caprices’ nos. 65–80 of The Disasters of War,” Apollo 107, no. 193 (March 1978): 186–91.

[12] Edith Helman, Trasmundo de Goya (Madrid: Revista de Occidente, 1963) and Jovellanos y Goya (Madrid: Taurus, 1970).

[13] Juan Turbio, Letter to the Editor, El conservador 18, April 13, 1820, 4.

[14] Additional discussion of the El conservador letter and Goya’s drawings of Inquisition persecutions is included in Reva Wolf, “The Victim as Martyr: The ‘Black Legend’ and Eighteenth-Century Representations of Inquisition Punishments, from Picart to Coustos to Goya,” in The Black Legend in the Eighteenth Century: National Identities under Construction, ed. Catherine Jaffe and Karen Stolley, forthcoming from Oxford Studies in the Enlightenment; for an interesting alternative interpretation of the El conservador letter, see Janis A. Tomlinson, Goya: A Portrait of the Artist (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 276–77.

[15] Eleanor A. Sayre, “An Old Man Writing: A Study of Goya’s Albums,” Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts 56, no. 305 (Autumn 1958), and, also by Sayre, “Eight Books of Drawings by Goya—I,” Burlington Magazine 106, no. 730 (January 1964): 19–31; Pierre Gassier, Francisco Goya: Drawings, The Complete Albums, trans. James Emmons and Robert Allen (New York: Praeger, 1973); Juliet Wilson-Bareau, Goya: Drawings from his Private Albums (London: Hayward Gallery, in association with Lund Humphries, 2001).

[16] So far, one volume of this new catalogue raisonné of Goya’s drawings has been published: Francisco de Goya (1746–1828): Dibujos: catálogo razonado, vol. II, 1771–92 (Madrid: Fundación Botín and Museo Nacional del Prado, 2018).

[17] Reva Wolf, “Goya and Freemasonry: Travels, Letters, Friends,” in Freemasonry and the Visual Arts from the Eighteenth Century Forward, ed. Reva Wolf and Alisa Luxenberg (New York and London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020), 73–93.

[18] José Manuel Matilla and Manuela B. Mena Marqués, Goya, Drawings: Only the Strength of My Will Remains (Goya, dibujos. Solo la voluntud me sobra) (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2019).

[19] Mark McDonald, Review of Goya, Drawings: Only the Strength of My Will Remains, by José Manuel Matilla and Manuela B. Mena Marqués, Master Drawings 59, no. 1 (Spring 2021): 89.

[20] Sayre, “An Old Man Writing” and “Eight Books of Drawings by Goya—I.”

[21] For example, the Album C drawings (such as fig. 6) are given a date range of 1808–14 in Goya’s Graphic Imagination, 170–75 (cat. nos. 49–51) and of 1814–23 on the website of the Prado Museum, at https://www.museodelprado.es/.

[22] Juliet Wilson-Bareau, Goya: Drawings from his Private Albums (London: Hayward Gallery, in association with Lund Humphries, 2001).

[23] Christian Viveros-Fauné, “Our Time Begs for Goya: ‘Goya’s Graphic Imagination,’ at the Met, Channels the Spirit of the Capitol Mob,” Village Voice, February 12, 2021, https://www.villagevoice.com/.

[24] Linda Yablonsky, “The Big Review: Goya’s Graphic Imagination at the Met,” Art Newspaper, March 3, 2021, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/.

[25] See also Chaparro, Goya’s Graphic Imagination, 286 (cat. no. 103).