The American Agriculturist: Art and Agriculture in the United States’ First Illustrated Farming Journal, 1842–78

by Stephen MandravelisStephen Mandravelis is an assistant professor of art history at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. He specializes in the art and material culture of the eighteenth and nineteenth-century United States, with a focus on the interaction of art and everyday life. Specifically, his research explores challenges to traditional artistic hierarchies by considering how vernacular objects and images helped shape broader conceptions of taste, geopolitical standing, and self-identity in the long nineteenth century. His work has been supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, SECAC, the Royster Society of Fellows, and others. His writing has appeared in Nineteenth-Century American History; Southern Things: A Place, Its People, and Its Things; and Not about Face: Identity and Appearance, Past and Present.

Email the author: Stephen-Mandravelis[at]utc.edu.

Citation: Stephen Mandravelis, “The American Agriculturist: Art and Agriculture in the United States’ First Illustrated Farming Journal, 1842–78,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 20, no. 3 (Autumn 2021), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2021.20.3.2.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

The American Agriculturist (1842–51, 1853–present), a popular trade periodical based in New York City that disseminated practical advice concerning the care, management, and improvement of the farm and rural home, has long been recognized by historians as one of the most significant farming publications of the nineteenth-century United States. Frank Luther Mott, author of the seminal A History of American Magazines (1931), stated that the Agriculturist “reached what is perhaps the most distinguished position ever held by an American agricultural periodical” in the wake of the US Civil War.[1] Similarly, agricultural historian Earl W. Hayter deemed the Agriculturist to be an “authoritative” and “leading” publication that “set the pattern” for rural communities.[2] This sentiment is furthered by contemporary historian R. Douglas Hurt, who lauds the Agriculturist as one of the two most important periodicals in the antebellum United States, and Albert Lowther Demaree—author of the authoritative (and only) monograph on the subject, The American Agricultural Press (1941)—who observed that the Agriculturist had “a more notable history than any of its rivals,” calling it one of the “most popular and influential journals of its day.”[3]

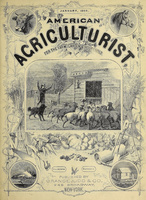

The Agriculturist’s own advertisement from January 1869 (fig. 1) anticipates many of these acclamations. The horizontal broadside is dominated by thirty small, rectangular woodblock engravings, each depicting a finely detailed vignette of animals, plants, or children at play. The engravings are stacked upon each other to form two large capital As, which serve as initials for the journal’s title stretched across the bottom edge. Boasts of the Agriculturist’s utility surround the leftward letter. “THE BEST PAPER” streaks across the top of the page, while “IN THE WORLD” cascades down the negative space of the letter’s counter. The clause concludes outside the leftward A’s diagonal strokes, where a list of fifty professions attests to the journal’s core audiences. It appeals, the advertisement informs the reader, not only to farmers, stockbreeders, and dairy producers, but also to wives, merchants, doctors, students, and—perhaps most unexpectedly—artists and engravers.

The text surrounding the right capital A elaborates upon the journal’s artistic character. “The American Agriculturist,” the broadside brags outside of the letter’s strokes, “FURNISHES EVERY YEAR FOUR HUNDRED to SIX HUNDRED BEAUTIFUL ENGRAVINGS, DRAWN AND ENGRAVED By the Best ARTISTS.” Building on the rhetoric of the opposing side, the right counter proclaims the Agriculturist as “THE BEST PAPER IN THE WORLD IN ILLUSTRATIONS,” noting only afterward in smaller, less ornate fonts its esteem in “Original Matter on AGRICULTURE, HORTICULTURE, HOUSEKEEPING, and for the BOYS AND GIRLS.” According to the advertisement, the Agriculturist was far more than a practical journal concerned with the betterment of the US farm; rather, it was an expansively illustrated publication that explicitly claimed artistic merit.

To contemporary audiences not familiar, or only passingly, with the American Agriculturist, the farming journal’s connection to art may seem surprising. But in its own time, this artistic association was both readily acknowledged and actively cultivated. The same year the journal published its broadside, the Friends’ Review noted that the Agriculturist’s “numerous, instructive, and beautiful” illustrations made it a worthy read for all those in the United States.[4] Only a year earlier, the Printer’s Circular suggested that the quality and extent of the these engravings made the Agriculturist “the best journal of its sort in the world.”[5] And, in 1870, the Aldine Press—one of the premier art periodicals in the United States—suggested that “among the illustrated papers of this country, The American Agriculturist is far ahead of its contemporaries in taste and attention to true art in its engravings.”[6] The Agriculturist’s editor and proprietor, Orange Judd (1822–92), carried this connection even further when he reminded readers, in 1877, that his journal was always intended to be “pleasing to the eye” and of “highly artistic” quality.[7]

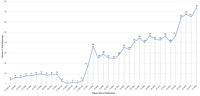

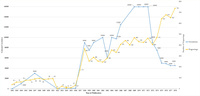

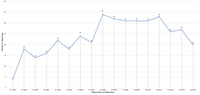

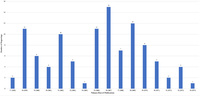

Yet, remarkably, in most modern accounts of the farming journal, its engravings are either ignored or mentioned only briefly, superficially, or pejoratively. Similarly, artistic and cultural historians have neither engaged with nor investigated them in any significant depth or detail. As a result, this core element of the Agriculturist’s materiality has been overlooked, and its role in shaping discourses about art, taste, and visual communication in the mid-nineteenth-century United States has never been duly examined. This essay aims to recover this lost visual history of the American Agriculturist by reassigning its engravings to their position of editorial importance. While the farming journal only modestly embraced illustrations throughout its first decade of publication, in its mature phase from 1858 to 1874, when the journal was edited by Judd, each volume contained hundreds of engravings (fig. 2), ranging from didactic depictions of machines, livestock, farmhouses, and crops to reproductions of popular paintings and pictorial compositions. I argue that, by bringing pictorial content to the Agriculturist’s readers, Judd, like his predecessors, aimed to enhance the practical and professional content of the journal through didactic engravings and diagrams; but by adding “artistic” engravings, whether reproductions of paintings or original compositions, he sought to establish greater cultural and aesthetic equity between city and country. Indeed, the Agriculturist’s engravings, during the first thirty-five years of the journal’s existence, chronicle the tribulations and successes of mid-century agricultural change as new technologies integrated themselves into its practice. Yet, they also register the gradual embourgeoisement of the farming population as it became increasingly familiar with the kind of art and subject matter that originated and was appreciated in the urban United States. In the end, however, the Agriculturist remained mindful of its primary goal as an agricultural journal and Judd was careful to create a distance between the world of art and the world of agriculture. While the Agriculturist could promote art through its associated prints, it was not a space containing “art.” Indeed, when Judd saw an opportunity for business growth in the sale of artistic prints, he set up a separate company to do so.

The discussion of the Agriculturist’s visual history in this article progresses along chronological lines. As the Agriculturist is largely unknown to contemporary audiences, a chronological account provides the best means to introduce readers to the larger history of the farming journal and frames its approach to art and engravings as the collective result of years of editorial developments, shifting cultural values, and technological advancements. One cannot understand the nuanced strategies of Judd without first knowing those of his predecessors. As such, the first section broadly discusses the field of agricultural journalism and analyzes the Agriculturist’s place within the historiography of the farm press. The second section examines the frequency and function of the Agriculturist’s engravings during the proprietorship of the journal’s founding editors, A. B. and R. L. Allen, from 1842 to 1851. The third section turns to the coeditorship of A. B. Allen and his young protégé, Judd, from 1853 to 1856, when financial hardships limited the incorporation of engravings. The fourth section focuses on the editorship of Judd from 1856 to 1878, during which time the presence and purpose of engravings expanded rapidly. Finally, the last section contextualizes these developments within the period’s debate over the “democratization” of art and outlines the middle ground upon which Judd established the journal’s visual system. This article, then, introduces an as-yet-unknown image provider to the chorus of such suppliers in the mid-nineteenth-century United States and establishes a framework from which to explore the evolving role of pictorial imagery in the rural culture of the period.

Farm Journalism and the Historiography of the American Agriculturist ↵

Agricultural literature first emerged in the United States in the late eighteenth century. At that time, the country’s agricultural system was in a state of stagnation, as the American Revolutionary War (ca. 1775–83) had decimated both farmland and a generation of its farmers, and exacerbated the already depleted soils and dwindling harvests resulting from years of inefficient farming practices.[8] Recognizing the unsustainability of the young country’s agricultural model, some farsighted gentleman farmers (i.e., affluent individuals who had the education, financial means, and luxury to indulge in experimental modes of agrarian production) turned to the rich and varied forms of farming literature produced during Britain’s Agricultural Revolution.

A broad term describing a complex array of scientific discoveries, social changes, and technological advances, the Agricultural Revolution had reinvigorated rural production in Britain in the 1700s and 1800s by promoting “improved” farming methods and techniques, such as fertilization, crop rotation, selective breeding, infrastructural improvements, and advancements in the design of farm machinery.[9] This information was initially disseminated through treatises and books published by scientists, academics, and agricultural societies, but by the end of the eighteenth century, a number of agricultural periodicals, such as Memoirs of Agriculture and Other Economical Arts (1768–1848), Letters and Papers on Agriculture, Planting, Etc. . . . (1780–1816), and Bell’s Weekly Messenger (1796–1896) were established. Like the books and treatises that preceded them, these journals were aimed at an educated audience, mostly other gentlemen farmers. They maintained the dense academic language of the scientific treatises and contained few, if any, illustrations.[10]

Wealthy and educated farmers in the United States began to acquire and reprint these British agricultural treatises and even began to publish some of their own to help combat the perceived slovenly farming practices of the time. Around 1800, they also began to organize agricultural societies. Even though membership to these societies was restricted along lines of class and race, the societies’ meeting proceedings and other correspondences were often published in local almanacs, such as Boston’s famed Farmer’s Almanack (1793), alongside agricultural calendars, articles reprinted from British agricultural periodicals, weather forecasts, and astrological readings. The young republic’s hearty newspaper network also poached agricultural passages from both these treatises and almanacs to produce their own farming columns. These short articles often discussed tips on soil treatment, planting schedules, weed elimination, and many other subjects.[11]

Agricultural historians do not generally credit these initial efforts with much practical change.[12] To keep things in perspective, only six agricultural treatises were published in the United States prior to 1840. These books were moderately priced but had low circulations, perhaps because they were written in the same scholarly style as their European counterparts, making them largely inaccessible to the average farmer. While almanacs were more widely read, their agricultural content shared space with other subjects. More problematically, almanacs often conflated scientifically advisable methods (such as fertilization or crop rotation) with the very superstitious, astrologically based practices (such as planting by cycles of the moon) that educated farmers were actively trying to discourage. Newspapers limited their agricultural advice to brief columns and rarely elaborated on, or explained the scientific rationale behind, the drastic changes to agricultural production they proposed. Exposure to agricultural information prior to the emergence of agricultural periodicals, then, was neither extensive, regular, nor wholly reliable. Moreover, the majority of farmers remained highly skeptical of these scientific farming practices, or “book farming,” as it was derisively termed. As most were subsistence farmers—that is to say, individuals who entirely depended on their crops for their livelihood—they were conservative and wary of change. Even if an older agricultural method resulted in yields that were lower than those promised in the farming literature, the guarantees of time-tested methods made them safe investments when compared to the unproven, “experimental” practices this literature advocated. Furthermore, the “improved” methods promoted by book farming often seemed and sometimes, in fact, were arduous, timely, and costly. For example, for much of the nineteenth century, it was less expensive to buy new property when a farm’s soil was exhausted than to preemptively invest in these farmyard improvements.

A concerted change to agricultural practice in the United States only commenced with the emergence of the farming periodical in 1810s. While these journals largely advocated the same scientifically based reforms promoted in earlier forms of agricultural literature, they differed from their predecessors in that they were inexpensive, widely accessible, and written in clear and simple language. They were edited by farmers for farmers and limited to the practices of agrarian cultivation. The first successful farming journal was John Stuart Skinner’s American Farmer (1819–34; Baltimore, MD). It was quickly followed by publications across the eastern seaboard, notably Solomon Southwick’s Plough Boy (1819–23; Albany, NY), Thomas G. Fessenden’s New England Farmer (1822–45; Boston, MA), Luther Tucker’s Genesee Farmer (1831–39; Rochester, NY), and Judge Jesse Buel’s Cultivator (1834–65; Albany, NY). Together, this first generation of farm journals disseminated agricultural information with a directness, professionalism, and relatability that cut across the period’s deep divisions in politics, geography, and ideology, and was able to effectively counter the public’s aversion to book farming. By the 1840s, agricultural journals had entrenched themselves in the farm and literary culture of the United States.[13]

The American Agriculturist was among the first periodicals comprising the second generation of farming journals. Founded in 1842 by two entrepreneurial siblings in New York City, Anthony Benezet (A. B.) and Richard Lamb (R. L.) Allen, the Agriculturist grew to a respectable size of about thirty thousand subscribers over its first decade of publication. But the farming journal attained a position of unsurpassed commercial dominance under the Allens’ apprentice and eventual successor as editor and proprietor, Judd. Each year between 1864 and 1878, the Agriculturist reportedly doubled the combined circulations of the three next largest farming papers and, at its commercial peak from 1869 to 1872, it was one of the United States’ five most popular periodicals of any genre.[14] During this period, the farming journal’s reported circulation of one hundred and sixty thousand exceeded the subscription totals of such renowned publications as Harper’s Weekly (1857–1916; New York City), Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News (1855–1922; New York City), and Godey’s Lady’s Book (1830–98; Philadelphia).[15]

The Agriculturist’s commercial success assured it a place of prominence in the canon of the nineteenth-century farm press. But the reasons for the journal’s popularity have only been casually explored. To date, the most extensive accounts of the journal’s history are the two short profiles, each only a few pages in length, written by Frank Luther Mott and Albert Lowther Demaree. These historians broadly attribute the journal’s popularity to its embrace of colloquial rhetoric; emphasis on scientifically driven agricultural methods; commitment to exposing humbug; and its general “non-political, non-partisan, non-sectional—in short . . . non-controversial character,” as one oft-cited period reviewer stated.[16] Later historians have been largely content to accept these conclusions, often only nominally recognizing the period’s most popular farming journal. The reasons for this paucity of historical investigation rest in the larger trends governing the study of agricultural journalism. The first is that historians tend to approach the farm press as a homogenous institution, relegating focused studies of individual journals to short reports that situate their espoused editorial missions within the farm press’s larger institutional framework.[17] In this sense, there has been little need to further investigate the Agriculturist, as Mott’s and Demaree’s short vignettes satisfy the summative reportage expected of individual journals.[18] Second, the Agriculturist’s commercial apex in the 1870s falls beyond the temporal scope of most farm-press historiographies. Nearly all scholars conclude their accounts of the farm press in 1860 with the “heroic” culmination of the first generation of farming periodicals.[19] While the Agriculturist and other second-generation farming journals are praised for greatly expanding access to agricultural information, they are typically framed as derivative enterprises that offered little new in terms of practical content or method.[20] Lastly, farming journals are often consulted as primary-source repositories for data on the economics and social development of agriculture in the United States. This function often supersedes the critical questions concerning their own status as ideologically constructed documents.

The Agriculturist’s association with art and engravings exists outside the scope of these extant scholarly interests. For historians employing the Agriculturist as a primary source document, its engravings do not merit comment. For those surveying the farm press, the illustrations merely serve as noteworthy corollaries. Mott, for instance, comments that the Agriculturist contained “woodcuts” from its very first issue and even remarks that the journal “had obtained a real distinction in these embellishments” by 1870, but he forgoes any specific description or analysis of the illustrations.[21] Similarly, Demaree only briefly notes that the Agriculturist “was also famous for its excellent illustrations; these were widely copied.”[22] Only Donald Marti affords modest consideration to the journal’s engravings. In his To Improve the Soil and the Mind (1971), Marti suggests that the Agriculturist “enticed readers . . . with cartoons, puzzles, and sentimental pictures with which to beautify their walls” and distributed these images “of gardens, gracious homes, and beautiful children” in an effort to turn farmers into gentlemen.[23] Marti correctly identifies the core imperatives of the Agriculturist’s artistic mission, but his dismissive characterization belies the complex and multifaceted visual character of the Agriculturist.

Art historians have similarly paid little attention to the engravings found in the Agriculturist. While studies of the pictorial press have become a critically rich subgenre of art historical discourse over the last twenty years, the Agriculturist seemingly offers few of the traits that helped popularize the study of illustrated magazines.[24] Unlike Harper’s Weekly or Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News, the Agriculturist offered no pictorial record of the period’s most pressing current events; unlike the Crayon or St. Nicholas, the Agriculturist employed few artists who would go on to lasting national fame; and unlike the Aldine, it introduced few innovations to popular artistic culture. After all, the majority of the journal’s engravings served as instructive illustrations of articles on the farm, garden, and household. On the other hand, the journal’s reproductions of artworks (or “sentimental pictures,” as Marti called them) embraced the conventions of a conservative style quickly giving way to the modernizing forms of the second half of the nineteenth century.[25] To many art historians, then, the Agriculturist appears to be a utilitarian document that exhibits little of the contemporary social reportage, visual creativity, and interpretative commentary traditionally foregrounded in art historical examinations of the pictorial press.

But it is exactly this distance from the traditional areas of art historical inquiry that frames the Agriculturist’s promotion of engravings as an index of the period’s larger changes in visual epistemology. The tenure of the journal’s first two editors—from A. B. and R. L. Allens’ initiation of the Agriculturist in 1842 to Judd’s retirement as the journal’s editor in 1878—corresponds to the period that art historian Michael Leja terms “the first wave of mass visual culture,” or the fifty years that saw the picture transform from something “rare and remarkable” to a “common object which permeated all socio-economic levels of the United States.”[26] Brought about by the significant advances in printing presses and other visual technologies, such as photography, lithography, and chromolithography, this epistemic shift brought easily reproduced and affordable images to new audiences. As a document ostensibly aimed at farmers and their families, the Agriculturist provides the means to examine the growth of visual culture in a populist rural context, as opposed to the more sophisticated sphere of urban centers.

The Allens’ Agriculturist, 1842–51 ↵

The Agriculturist’s founding proprietors, A. B. Allen (1800–1892) and R. L. Allen (1803–69), were born on a small farm in Westfield, Massachusetts.[27] In the early 1830s, the brothers moved to Buffalo, New York, where they opened a successful agricultural-supply warehouse and amassed a small fortune speculating in the region’s emerging land markets. After the Panic of 1837 bankrupted these enterprises, the Allens moved to New York City, where they founded a burgeoning publishing center of unparalleled size and logistical promise, but one without a successful agricultural journal.[28] Given the region’s extensive agrarian markets, the siblings saw potential for a regional farming periodical and they began raising funds for their own journal, to be titled the American Agriculturist, in late 1840.

The initial volume of the Agriculturist was published in April 1842. Printed by George Peters at 36 Park Row in lower Manhattan, it consisted of thirty-two royal octavo pages (about 6 by 9.75 in.), which was considerably smaller than the newspaper-sized quarto pages (around 9 by 12 in.) preferred by other farming journals of the period. The Allens believed this smaller size would enable readers to more easily store—and, by dint, reference—their journal on bookshelves.[29] The brothers priced a yearly subscription at $1, placing it within the means of most middle-class families.[30] The Agriculturist would maintain this relative affordability throughout its publication in the nineteenth century: the subscription price remained at $1 until volume 24 (1865), when it was raised to $1.50 per year; and then again raised to $1.60 per year twelve years later, in volume 36 (1877).

Editorially, the Allens claimed no special knowledge or superiority over the farm journalists who preceded them. Like other scientifically minded proponents of modern farming, they primarily sought to continue advancing “the pursuit of agriculture in its broadest sense.”[31] The Allens were advocates of “improved” farming techniques and envisioned the Agriculturist as a journal that promoted “an enlightened system of husbandry.”[32] They emphasized the subjects of planting, harvesting, husbandry, and horticulture, as well as advocated new scientific innovations, such as crop rotation, fertilizing, and deep plowing. The brothers also imbued the Agriculturist with nationalist and moralist directives. They argued that farming constituted “the basis of our national virtue and national wealth” and lamented that the occupation was “in its real merits, estimated below that of other professions in our land.” They therefore promised their readers to make farming “more popular and attractive” and to fashion agriculture as a distinctly modern profession.[33]

The Allens considered wood engravings to be an integral component of the journal’s “popular and attractive” allure. Illustrations were not wholly new to farming journalism; first-generation periodicals, such as New York Farmer (1828–32; New York City), and almanacs had occasionally included small didactic illustrations, usually as inserts, but they were neither common nor finely executed.[34] Accordingly, the brothers’ prospectus advertised that each issue of the Agriculturist would contain at least one or two “fine” engravings. But they were quick to temper any grandiose expectations, noting that the journal’s octavo format did not afford the space for the artfully engraved plates found in more “elegant” art publications. The editors assured readers, however, that the Agriculturist was “sufficiently large” for portraits of animals, machines, and plans for farms and buildings.[35]

In total, the first volume slightly surpassed these modest projections. It contained thirty-eight engravings published over its twelve issues. The contents also closely conformed to the brothers’ predictions, with fifteen mechanical diagrams, nine images of animals, six schematics of farm buildings, six depictions of plants, and two urban landscapes. Each of these engravings related to a specific article and they were always situated within the text or in its immediate vicinity. They operated as “epistemic images,” Lorraine Daston’s term for pictures that enlarged and validated the texts they illustrated.[36] Like most such images, they were generic—one might call them idealized—images offering the “best” representation to facilitate the widest array of didactic inquiries.[37] The journal’s depiction of a sisal hemp plant from January 1843 (fig. 3), for example, evenly distributes the seventeen slender leaves of the Mexican succulent across the page, displaying them, as the editors write, for “the consideration of our southern friends.”[38] No description accompanies the engraving, indicating that it alone was sufficient to provide the reader with the necessary information.

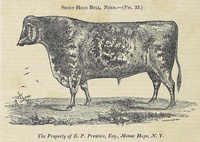

But not all images were so generic. In the journal’s account of the New York State Agricultural Society’s livestock competition from February 1843, an engraving portraying the short-horn bull Nero (fig. 4) is treated as a genuine stand-in for the animal. “Here he is,” the Allens summarily write, their rhetoric avoiding any suggestion of the depiction’s status as artistic mediation.[39] The artist who drew Nero, Thomas Kirby van Zandt (1814–86), was not acknowledged in the Allens’ commentary, despite his status as a well-known New York painter of horse and bull portraits for wealthy New Yorkers.[40] The depiction of Nero provides a permanent record of direct observation and experience—the reader could “see” Nero without physically being present. Like the engraving of the sisal plant, it was an informative, epistemic image meant to facilitate farmers’ visual assessment of bulls encountered over the course of their own agricultural activities. Despite being the work of a well-known artist, Nero would not have been seen by the readers of the Agriculturist as a work of art.

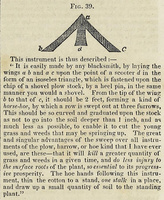

Several of Allens’ engravings facilitated the comprehension of complex textual material. An example of this function can be found in the schematic rendering of a cotton sweep, a tool that weeds the area surrounding cotton plants or corn stalks (fig. 5). The engraving elucidates the associated article’s description of the instrument’s construction, rendering it schematically from above, with the key parts marked a, b, c, and d. “The sweep,” the article writes:

is easily made by any blacksmith, by laying the wings a b and a c upon the point of a scooter d in the form of an isosceles triangle, which is fastened upon the chip of a shovel plow stock, by a heel pin, in the same manner you would a shovel. From the tip of the wing b to that of c, it should be 2 feet, forming a kind of horse-shoe . . . this should be so curved and graduated upon the stock as not to go into the soil deeper than 1 inch.[41]

In addition to the epistemic illustrations of the journal, it featured a pictorial masthead (fig. 6). Framed by the Agriculturist’s arching title and a quote commonly attributed to George Washington, “Agriculture is the most healthful, the most useful, and the most noble employment of Man,” the roughly executed vignette visually indexes the journal’s content. Read from left to right, the engraving depicts farm buildings, crops, insects, tools, livestock, homesteads, and agricultural procedures—all subjects that directly correlate to the Allens’ editorial interests and, to paraphrase Maria Grazia Bartolini’s analysis of illustrated title pages (which play a role similar to that of mastheads), exemplify and expand upon the textual content.[42] The plentiful and productive farmscape thereby serves as an aspirational model for readers, suggesting an equally expansive yield of crops and livestock awaits the dedicated reader who closely follows the journal’s prescribed methods. The quote from Washington enhances this association by tying the aspirational production of the Agriculturist’s reader to the Agrarian Myth, or the widely held cultural belief in the United States that the simple, self-sufficient existence of independent farmers constituted the most moral, productive, natural, and heroic form of life—one akin to the perceived republican paradises of Greece and pre-imperial Rome.[43] While the inclusion of the illustrated masthead was highly conventional for the time, its presence demonstrates the Allens’ at least passing awareness of such socio-artistic principles, such as the Agrarian Myth, Georgic literature, and rural beauty. The exclusion of these aesthetic conventions from the journal’s interior didactic engravings enhances the intentionality of their epistemic and illustrative nature.

At the end of the first volume, the Allen brothers promised to significantly bolster the frequency of illustrations in volume 2 (1843), and they indeed increased the total number of illustrations by 60 percent to sixty-one engravings.[44] That figure grew steadily over the following years. By volume 5 (1846), the total had risen by another 30 percent, to seventy-nine illustrations, and it had increased again to ninety-six illustrations by volume 7 (1848). This additional visual content neither signaled a shift in aesthetic approach nor a greater diversity of function. The engravings continued to show the same subjects—machines, animals, schematics, and plants—and they retained their didactic function.

The increase in pictorial content likely resulted both from the Allens’ realization that the illustrations added appeal to their journal and from their growing financial liquidity. At the beginning of volume 3 (1844), A. B. Allen explicitly links the quantity of the journal’s engravings to his available capital, explaining that he could provide a “handsomer” periodical “with more illustrations” only if he received more subscriptions.[45] The parallel growth of both total engravings and subscriptions during the 1840s supports this correlation (fig. 7), as the apex of engravings per volume (ninety-six in volume 7 [1848]) coincides with the journal’s highest reported subscription totals (about thirty thousand). During this period, the Allens also began to supplement their income with other business ventures. In January 1847, the brothers incorporated, forming A. B. Allen & Co., and they opened an agricultural supply store at 189 Water Street in Manhattan. The warehouse doubled as the Agriculturist’s editorial office, and the store’s success gave the brothers an income stream independent from the journal. In June 1848, the brothers again expanded, buying Josiah Tatum’s Farmers’ Cabinet and American Herd Book (1840–48; Philadelphia) and entering into a partnership with J. M. Saxton of Boston, giving the journal three centers of distribution.[46]

The Allens’ acquisitions in 1848 were perhaps too aggressive, though, as a number of circumstantial factors suggest that the journal began experiencing financial hardships in the following years.[47] Indeed, historians often describe the Agriculturist of the late 1840s as a journal on the brink of financial ruin.[48] But despite the lower number of subscriptions, the Allens only slightly decreased the number of engravings between volume 7 (1848) and volume 8 (1849). And, over the following two years, they actually increased it, first to eighty-nine engravings in volume 9 (1850) and then to ninety-four in volume 10 (1851). This resistance to decreasing the number of engravings, even when faced with financial hardships, indicates that the editors considered the illustrations to be important enough to warrant the continued expense. The brothers effectively doubled down on the “modernizing” novelty of the farming journal’s engravings in the hopes that this visual content would attract new subscribers. The gambit proved unsuccessful. In October 1851, the Allens announced that the Agriculturist would suspend publication at the conclusion of volume 10 (1851). The journal would be merged with a new literary venture, the Plow (1852), to be edited by one of the Allens’ long-time correspondents and assistant editors, Solon Robinson.

Publicly, the Allens stated that they were retiring from the “arduous duties of editors” to better meet the demands of their other agricultural businesses.[49] But their abandonment of the Agriculturist signaled a lack of public enthusiasm, especially as the merger with the Plow was almost purely nominal. The “new” journal retained the same thirty-two page imperial octavo format, double-column layout, typeface, and frequency of engravings as the Agriculturist, as well as the same office, publisher, staff, network of correspondents, and agents. Moreover, all subscriptions to the Agriculturist carried over to the Plow, and the Allens remained its proprietors in addition to regularly contributing articles.[50] While the brothers proclaimed every intention of later resuscitating “an enlarged and highly improved” sixty-four-page Agriculturist, the merger with the Plow was popularly understood as the death of the ten-year-old farming periodical.[51]

A. B. Allen, Orange Judd, and the Absence of Engravings, 1853–56 ↵

The opportunity to resurrect the recently defunct Agriculturist arose only two years later. The Plow succumbed after one volume and a legal scandal involving one of the Allens’ employees forced the closure of two other recently acquired agricultural periodicals in the summer of 1853.[52] Without other recourse, A. B. Allen—his brother had moved to Buffalo to open a second agricultural warehouse—announced that the Agriculturist would be revived for an eleventh volume, beginning in September 1853.[53]

The reissued Agriculturist was a radical departure from its earlier iteration. The revised journal abandoned its predecessor’s octavo format for the larger and more conventional quarto size. It featured a new three-column layout, a crisp typeface, and a decreased size of only sixteen pages. The old masthead vignette was replaced by a new purely textual header (fig. 8). The new Agriculturist more closely resembled a newspaper than a farming periodical—a design decision likely intended to reduce postal rates.[54] Finally, A. B. began publishing the journal weekly in order to be more up to date on current market prices and economic reportage. He hoped that the Agriculturist, as the only farming journal in the United States to be published weekly, would be indispensable to the business-minded farmer wanting to stay abreast of the changing price for produce, cattle, and other products.[55]

The most significant boon for the reissued Agriculturist, however, was A. B.’s decision to hire Judd as his associate editor. Born near Niagara Falls, New York, in 1822, Judd graduated in 1850 from the Analytical and Agricultural Chemistry program at Yale University, where he became a devoted advocate of the methods of renowned European agriculturists Justus von Liebig and Jean-Baptiste Boussingault. Judd first came to A. B.’s attention early in 1852, when the young agricultural chemist gave a series of seventy-two lectures on scientific farming in Connecticut.[56] A. B. was impressed with Judd’s ability to clearly and compellingly explain scientific theory and thought that such rhetorical skill would enhance the accessibility of his journal. The next year, A. B. asked Judd to join his editorial team as the young agriculturist passed through New York City while en route to a teaching position in Chicago. Judd abandoned his westward prospects as he saw potential to educate more farmers through the journal than he could teach students in the classroom.

While the new coeditors promised that the eleventh volume would continue to feature “numerous engravings” for the educational benefit of their subscribers, the new Agriculturist did not maintain the same commitment to illustration as its predecessor.[57] The first two issues contained five engravings apiece, but the remaining twenty-four issues totaled just fourteen. Unsurprisingly, the claim to feature “numerous engravings” was dropped from the prospectus in the middle of the volume. The paucity of visual matter continued throughout the shared editorships of A. B. and Judd: volume 12 (1854) featured just six engravings, volume 13 (1854–55) contained fourteen, and volume 14 (1855) included only nine. The illustrations that did appear in the journal adhered to the same subjects and didactic purposes as those in the earlier Agriculturist.

Neither A. B. nor Judd directly commented on the journal’s turn away from visual content. If the cost of engravings had indeed contributed to the demise of the first Agriculturist and the Plow, the decision to withhold visual content would suggest a more conservative fiscal strategy. A. B. and Judd often noted that the journal was not a profitable venture for Allen & Co., and they regularly described the journal as their magnanimous “contribution to the cause of improvement.” This account of monetary self-sacrifice was surely exaggerated for public goodwill, but A. B. and Judd were indeed on shaky financial grounds at the time.[58] Moreover, the logistical demands of publishing a weekly journal did not easily comport with the timeline for producing original woodblock engravings. The Agriculturist was put to press either Sunday afternoon or Monday morning and mailed to subscribers every Tuesday. This schedule left only five days to plan, write, and set the type for the next issue. In the early 1850s, a talented engraver required a few days to a week to produce a quality woodcut at a reasonable price.[59] With this time-sensitive schedule and labor-intensive production process, the editors either had to reuse existing woodcuts, plan for the illustrations’ inclusion in advance (which did not comport with the journal’s emphasis on topical subject matter), or pay a premium for expedited engravings.

The weekly Agriculturist therefore approached illustrated content in a manner similar to that of its predecessor: engravings were luxuries whose inclusion often rested on the journal’s financial flexibility. With a subscription list estimated to have been only in the hundreds, A. B. and Judd simply had less available capital. Yet circumstances did begin to improve, as Judd, who had taken over the majority of the journal’s editorial operations while A. B. attended to the warehouse, steadily built a receptive audience. By February 1855 the Agriculturist reported that its subscription lists had doubled.[60] A little over a year later, in 1856, A. B. was again expressing his intentions to return to solely managing his agricultural warehouse, and on March 3, the Agriculturist’s founding editor announced he had sold his interest in the periodical, complete with “its good will, type, and fixtures”—as well as list of 812 subscribers—to Judd for $226.[61]

The Embrace of Engravings under Judd, 1856–78 ↵

Within two years of Judd’s acquisition of the Agriculturist, the former agricultural chemist had turned the struggling publication into one of the country’s most widely read farming journals. The dramatic increase in popularity stemmed from several changes.[62] First, Judd returned the Agriculturist to a monthly publishing schedule, expanding each issue to twenty-four pages in order to make up for the perceived loss of content.[63] Second, he initiated an aggressive advertising campaign, capitalizing on a marketing strategy in which the Allens had never seriously engaged. Third, he engineered the importation and free distribution of twenty-five thousand packets of sorghum seeds (a new and more formidable variety of wheat) to the journal’s subscribers. Fourth, in 1858, Judd started a German-language edition of the Agriculturist, tapping into a hitherto untouched demographic market.[64] Last but not least, he cultivated a cordial editorial persona who stridently fought for the interests of his readers. He held all the journal’s content (including its advertisements) to a high standard of veracity, even penning a section in each issue that exposed all varieties of prominent scams, false reports, and humbug. These protectionist tendencies, coupled with his clear, familiar, and relatable voice, endeared Judd to readers, and by the start of 1858, the Agriculturist reported a circulation approaching one hundred thousand.[65]

The innovative advertising and subscription practices and the revised publishing schedule once again afforded revenue and time necessary to include wood engravings. The Agriculturist experienced an exponential increase in visual content during the first years of Judd’s tenure. While volume 15 (1856) contained only thirty-two engravings (itself a substantial increase from the nine engravings featured in the previous volume), volume 16 (1857) contained 173 engravings in its twelve issues, a 456 percent increase from the year before.[66] That number rose by another 105 percent in volume 17 (1858) to a total of 366 engravings—nearly equaling the volume’s 380 pages. The same two-year period, then, which saw the Agriculturist subscription numbers grow from 812 to nearly one hundred thousand, also saw the journal’s engravings similarly increase from nine to 366. The journal’s volumes would continue to average just under 350 engravings throughout the 1860s, with the individual total per volume spiking to over six hundred engravings in 1875 and reaching a peak of 739 engravings in the 501 pages of volume 38 (1878).

Importantly, Judd’s acquisition of the Agriculturist coincided with technological advancements that greatly facilitated the production of illustrated periodicals. The introduction of the Rampage Perfecting Press (1855) and Taylor’s Perfecting Press (1858) significantly enhanced the speed at which image and text could be printed together.[67] Indeed, the first self-defined “illustrated periodicals” in the United States, Gleason’s Pictorial in Boston and Frank Leslie’s and Harper’s Weekly in New York, were all inaugurated just a few years before the Agriculturist’s own visual turn. The success of these periodicals demonstrated the economic viability of Judd’s strategy and frames his embrace of visual content, in part, as an attempt to keep up with the competition.

Initially, Judd justified the presence of engravings in the same way as the Allens. Emphasizing their didactic nature, the editor assured readers in January 1859 that he had no intention of publishing a “picture book”—a derisive label devised by high-minded cultural commentators to describe periodicals that contained “amusing” pictures offering no educational benefit other than “abstract attractiveness.”[68] The wood engravings in the Agriculturist, Judd explained, rendered the material culture of the farm “as if one looked at the objects themselves,” more easily communicating information on animals and tools than long columns of text.[69] The engravings retained the same subject matter and didactic function as the illustrations in the first Agriculturist, and Judd promised that the journal would remain a practical and scientific publication that only offered “really instructive” pictures.[70] By volume 19 (1860), though, such rhetorical defenses of engravings had ceased, suggesting Judd’s audience had embraced the journal’s visual turn. Indeed, the editor would later boast that “not one subscriber in a hundred . . . would part with the knowledge and pleasure” derived from the journal’s new emphasis on imagery.[71]

Judd, however, also began to expand the range of images in the Agriculturist. An article entitled “The Two Pictures,” published in volume 16 (1857), tells a story, probably apocryphal, in which two of the Agriculturist’s editorial assistants purportedly stumbled across a drawing of the dilapidated farm of Mr. B. in the drawers of the journal’s offices. Knowing that the “energetic” Mr. M. had bought the old farm the previous summer, the two assistants dispatched an artist to obtain a present sketch for comparison. The two depictions were reproduced at the top of the page (fig. 9), with the shabby property of Mr. B. at left and the renovated one of Mr. M. at right. The article describes the appearance of the before-and-after pictures, calling attention to the condition of the fences, animals, houses, compost heaps, and woman walking to the outhouse in the upper right of each image.[72] It concluded by telling readers that the images “will bear studying,” hinting that more instruction can be gleaned from the pictures. Readers were to determine for themselves that the farmyard of Mr. M., with its straighter fence, fatter animals, cleaner and lusher yard, better-supplied toolshed and barn, and more orderly house, was the preferable of the two properties. From this, they could conclude that Mr. M.’s more productive farm resulted from the owner’s hard work, intelligent management, and his active application of the “improved” farming techniques promoted by the Agriculturist. The image’s purpose deviated from the traditional function of engravings in the Agriculturist by not merely representing an animal, plant, or tool but also by presenting an image that needed to be “read” to understand its life lesson about hard work and applying oneself. The didactic depictions of animals, tools, farm structures, plants, and machines never ceased during Judd’s tenure as editor of the Agriculturist, and they remained the most common type of engraving found in the journal. However, engravings that told a story or taught a lesson, such as the one accompanying “The Two Pictures,” began to appear with increasing frequency and quickly became a distinguishing aspect of the journal, with Judd noting in 1859 that engravings enhanced the “peculiar worth” of his journal.[73]

This “worth” also stemmed from another new type of engraving introduced to the Agriculturist in 1858. In the August issue, Judd printed The Green Lanes of England (fig. 10), an illustrated piece of sheet music originally published by the London Illustrated News a few months earlier. The song’s bar lines and lyrics occupy the lower half of the full-page engraving, while a depiction of eight small children playing along the edge of an idyllic wooded grove appear in the upper half. The editor acknowledged that Green Lanes was an atypical inclusion for an agricultural journal but argued that the “refreshing” scene would help assuage the heat of the “torrid month” of August, as well as appeal to the “general interest” of readers.[74] Gone, apparently, was his earlier objection to the “abstract attractiveness” of “picture book” images, as Judd added that he saw no reason why those involved in rural occupations could not also enjoy “some of the more pleasant things” that “interest and elevate the feelings.” He even concluded the article on The Green Lanes of England by proposing that, if subscribers enjoyed the engraving, he would happily publish other pictorial compositions when space in the journal allowed.

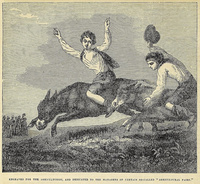

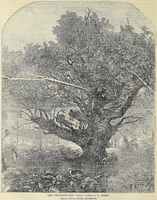

The Agriculturist published three more “pictorial” engravings in volume 17 (1858): first a depiction of two boys racing horses (fig. 11); then a scene of spectators watching a horse race (fig. 12); and, finally, a reproduction of a painting, The Monarch Oak (fig. 13), by the British landscapist Henry Mark Anthony. The presence of these narrative genre scenes continued to grow in subsequent volumes, with each issue of the journal from volume 18 (1859) onward containing at least one or two of the half- or full-page pictorial engravings (fig. 14). The journal averaged eighteen such engravings per volume between 1859 and the end of the US Civil War in 1865, before nearly doubling that total to thirty-four in volume 25 (1866). The journal continued to average just under thirty-two pictorial engravings per volume over the next five years before their frequency began to decline in volume 31 (1872). In total, the Agriculturist published over four hundred pictorial engravings during its commercial peak from 1858 and 1874, and its editor often boasted of the enormous cost of this investment in visual material. In volume 28 (1869), he claimed to spend over $13,000 on the engravings.[75] In volume 29 (1870), that monetary expense rose to a reported $15,000, and by volume 36 (1877), to over $20,000—a total that Judd claimed was higher than the amount most $3 and $4 illustrated periodicals spent on their own illustrations.[76]

The expanded prominence of pictorial engravings necessitated profound changes to the journal’s operations and physical format. As the pictorial engravings had to be printed on better-quality presses than the journal’s ordinary text, Judd devised an entirely new printing schedule and layout for the Agriculturist.[77] In 1866, he added a three-quarter-sheet engraving to its title page below the Agriculturist’s textual masthead (fig. 15). The large engravings ranged from scenes of pioneers readying for a journey into the wilderness to renderings of domesticated livestock and were usually anchored by a short expositional article at the base of the page. A few years later, in 1869, the Agriculturist added an embellished cover page (fig. 16) that protected the integrity of the “valuable” title page and allowed the journal’s art department to present a “pleasing” design.[78] The ornamental framework of agricultural implements, ripe vegetables, and luscious crops formed a template for five engravings—one circular vignette in each corner and a large rectangular scene at center—that changed monthly. With this decorative cornucopia, the cover embraced notions of abundance and aspirational success similar to the masthead vignettes of the Allens’ Agriculturist.

More importantly, the pictorial engravings expanded the journal’s editorial mission, for they signaled Judd’s aspiration for the Agriculturist to be not just a resource for farmers but to operate as tastemaker for rural families in the United States. “Why should not the farmer’s own family paper or magazine have not only a practical character,” he rhetorically proposed in 1859, “but also be got up in the best style and in a form to please, instruct, and inculcate true artistic taste?”[79] Judd believed that art did not solely belong to urban dwellers but could—and should—enrich the homes and lives of rural populations. After all, the editor explained, “other classes [by which he probably meant the urban wealthy and middle classes] have access to avenues of art that are denied to the family isolated upon the farm,” before adding that “the Agriculturist it is hoped will in some degree make up for this deficiency.”[80] He then boasted that his assistants had “untrammeled discretion” to procure pictures, “not black blots, called pictures for want of other names, but really fine artistic engravings—those that cultivate true taste in the eye and mind, and that both please and instruct.”[81] The significance of these proclamations does not necessarily rest in their novelty—similar rhetorical boasts of artfulness and aesthetic cultivation regularly appeared in pictorial journals at the time—but in the fact that they appeared within a space previously reserved for practical professional advice. As opposed to the Allens’ Agriculturist, which concerned itself solely with matters of farming, Judd’s journal explicitly adopted a mission of artistic cultivation, joining the larger effort by mid-nineteenth-century periodicals and organizations like the American Art Union to bring art to those throughout the United States.[82]

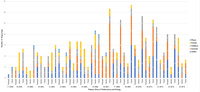

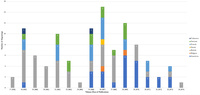

Accordingly, the subject matter, stylistic approaches, and moralizing messages of these pictorial engravings closely followed conventional modes of art then popular in both the United States and Europe. Indeed, Judd’s selection for the Agriculturist closely mirrored the types of pictures promoted by other prominent cultural producers in the United States—lithographic firms, such as Currier & Ives and Louis Prang; pictorial magazines, such as the Crayon, St. Nicholas, and Appleton’s; and numerous others—that depicted life in the United States as one idyllically brimming with patriotic optimism, familial harmony, imbued with the majesty of the American wilderness, and playful yet moralized adventure.[83] A statistical breakdown (fig. 17) of the Agriculturist’s pictorial engravings demonstrates the consistency of these themes. The greatest percentages of these scenes—just under 44 percent (or 176 of the 402 pictorial engravings)—highlighted the animals, human adventures, and restorative joys found within the uncultivated setting of the wilderness. Seventy-two of these nature-focused pictorial engravings took wild animals or livestock as their central subjects. Some, such as the reproduction of Rosa Bonheur’s painting A Group of Highland Cattle (fig. 18), from 1866, or the family of birds in Just Hatched (fig. 19), an original composition drawn and engraved for the Agriculturist in 1871, served as didactic examples of breeds that compliments article’s descriptions their behavior, while others, such as Many a Slip between Cup and Lip (fig. 20) from 1867 and Coming Events Cast Their Shadow (fig. 21), an engraving based on a drawing by Henry Herrick (1869), showcased the perils of surviving within the natural environment. Hunting scenes, such as The Last Shot (fig. 22), a reproduction of a painting by Richard Ansdell published by the Agriculturist in 1868, were also popular, but the vast majority of the fifty-nine pictorial engravings featuring adults and families in the uncultivated landscape were either scenes of work, such as A Change of Pastures (1869; fig. 23); playful excursions, like A Family Sleigh Ride (fig. 24) from 1865; or coy flirtations, as in The Passing Shower (fig. 25) from 1859. The forty-one engravings of children in the wilderness once again celebrated the innocence of virginal landscapes, such as in the peaceful communion between child, animal, and nature in Jolly Companions from 1869 (fig. 26), a reproduction of a painting by Julius Schrader, or as sites for the lighthearted play of children, as in Having a Good Time (fig. 27) from 1865. Rounding out the 176 pictorial engravings of natural settings were four depictions of plants set within traditional conceptions of landscapes, such as An Ornamental Group of Aquatic Plants (fig. 28).

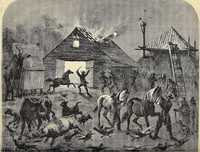

The second-most-frequent type of pictorial engravings found in the Agriculturist were farmyard scenes, which made up 33.5 percent (135 of 402) of the total. The same three subjects once again inhabited the farmyard setting: thirty-nine engravings primarily depicted livestock within stables or other areas of the farm, such as the F. S. Church’s humorous The Modern Tantalus (fig. 29) from 1872. The majority of the seventy-five farmyard scenes depicting adults and families once again glorified the act of farm work, such as in The Harvest (fig. 30) from 1865 or The Steam Plow in Operation (fig. 31) from 1871, although several “eventful” or playful scenes, such as The Burning Barn (fig. 32) from 1866 and A Little Rustle Brought Her to Her Consciousness (fig. 33) introduced variety to this particular genre. The twenty farmyard scenes of children, meanwhile, almost exclusively showcased the innocent games, frivolous activities, and sometimes even mischievous actions of boys and girls. Little Mischief (fig. 34), for instance, published in 1869 from a sketch by Thomas Worth, shows a child tantalizingly dangling some hay just out of the reach of a hungry horse.

Interior scenes constituted the final 22.6 percent or ninety-one of the 402 pictorial engravings in the Agriculturist. Unsurprisingly, wholesome depictions of the family, such as The Christmas Tree (fig. 35) and Feeding the Sparrows (fig. 36), dominated these domestic settings. More humorous depictions of homely activities, however, were primarily the subject of the twenty-nine of these engravings that featured children, such as The Railroad Ride (fig. 37), where a team of children create their own train from household materials in their living room, and The First Smoke (fig. 38) from 1871, which highlights the nauseating aftermath of a young boy’s first puff of a pipe. The interior scenes of animals also followed this humorous tone. Making up only fifteen entries in the set of interior engravings, pictures such as The Faithful Guard (fig. 39) and The Artist’s Pets (fig. 40), after Edwin Landseer, foregrounding the loyalty and humor of humankind’s closest companions.

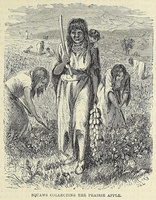

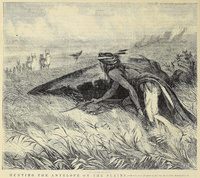

This categorical breakdown of the Agriculturist’s pictorial engravings does not, however, pay credit to the vast number of thematic relationships developed over the set of pictures. In addition to expected commentaries on agrarian work and gender relations, the Agriculturist’s pictorial engravings also provide insight into the period’s developing discourses on westward expansion, technological development, and the formation of nationalism within a global context. There were, for example, pictorial series on Native American life, such as William M. Cary’s Squaws Collecting the Prairie Apple (fig. 41) and Hunting Antelope on the Plains (fig. 42), which were both commissioned by Judd exclusively for the Agriculturist in 1870 and 1871, respectively; foreign locales, such as Drying and Packing Tea by the Chinese (fig. 43) and Treading Out Grain in Egypt (fig. 44), a reproduction of Jean-Léon Gérôme’s painting Treading Out the Grains in Egypt (ca. 1859; private collection), once again from 1870 and 1871, respectively; and fanciful scenes of imagination, such as A Mouse’s Dream—A Cat in Court (1863; fig. 45), Fairy Marauders (1870; fig. 46), and Gulliver before the Citizens of Brobdingnag (1874; fig. 47). The contribution of these thematic collections to the growth and development of larger cultural trends in the visual culture of the mid-nineteenth-century United States requires further consideration.

As suggested in the statistical breakdown of the Agriculturist’s pictorial engravings, this effort to bring art to rural populations relied upon reproducing popular paintings. Indeed, of all the Agriculturist’s pictorial engravings published between 1858 and 1874, at least 102 (25 percent) can be identified as reproductions of paintings or well-circulated fine art prints (fig. 48). This percentage was even greater over the first five years, when reproductions comprised about 45 percent of all pictorial compositions in the journal. The vast majority (70 percent) of these pictures were sourced from British painters (fig. 49), including Edwin Landseer, Joseph Clark, Alfred Elmore, and Walter Goodall. While the later 1860s witnessed a continued emphasis on British art, the journal also began to reproduce works by French, German, and US artists. By the early 1870s, though, Judd had largely ceased publishing reproductions of paintings in favor of original engravings. Judd hired a team of artists and engravers in the mid-1860s to reduce the costs of outsourcing the production of the journal’s pictures.[84] This in-house team initially only produced the journal’s didactic engravings, but they soon began to create their own pictorial compositions—a shift that allowed Judd to position the Agriculturist as a producer of artistic content in addition to a purveyor of it. During the later 1860s and 1870s, Judd also hired artists working in the United States, such as Edwin Forbes, William de la Montagne Cary, Thomas Worth, Granville Perkins, and Jerome Thompson, for special prestige assignments.

Yet, unlike many of the prominent New York art institutions, such as the American Academy of Fine Arts and the National Academy of Design, or even other contemporary art periodicals, the Agriculturist did not seek to elevate the status of US artists or justify their talents in relation to international standards. Indeed, the Agriculturist did not overly concern itself with the nationality or individuality of the artists whose work it reproduced. While the pictorial engraving was always identified as either a reproduction or an original composition, the attributions to specific artists were inconsistent and their nationalities rarely mentioned. For example, the Agriculturist’s version (fig. 50) of Edwin Landseer’s A Distinguished Member of the Humane Society (1831; Tate, London) is a relatively faithful reproduction of the original, but the accompanying article states only that the engraving “is a portrait by Landseer” and that most readers should recognize the Newfoundland dog sitting calmly on the ledge in the picture as “an astonishingly faithful representation of a good Newfoundland.”[85] The questions of who Landseer was, why he was important, and what specifically made the “portrait” astonishing were taken to be self-evident and left for the reader to determine on their own. As the Agriculturist’s own artists produced ever more of its pictorial content, authorial attribution became an even lesser concern. One of the sole artists to gain extensive discussion within the Agriculturist was Rosa Bonheur, whose paintings were reproduced four times between 1862 and 1869. Judd praised Bonheur as “among the most eminent of living painters of animals, if she be not, indeed, the most celebrated of all” and noted that her compositions contained a “vigor and action which but few artists are capable of imparting to their works,” her talents conveyed “wonderful individuality,” and the “marvels of [her] color and drawing” were unsurpassed.[86] Even in these instances, though, the discussion of Bonheur’s artistic genius constitutes only a small part of the accompanying article. Of the three columns of text accompanying the reproduction of Bonheur’s Group of Highland Cattle (fig. 19), for instance, Judd’s praise of the artist fills only the first column, while a discussion of the physical and nutritional merits of the Highland Cattle breed constitute the final two columns. Just like the journal’s epistemic engravings of agrarian material culture, the “art” of the Agriculturist’s pictorial engravings remained secondary to their ability to provide opportunities for instruction.

The educational imperative of the pictorial engravings is perhaps best understood as a response to the Agriculturist’s development from a purely agricultural periodical into a general interest and family one. As the journal grew in subscribers, Judd needed to include content that would appeal to readers who had little interest in the optimal operations of the family farm. Early in his tenure as editor, he had added a section devoted solely to matters of housekeeping, intended for rural women, and, later, a section with puzzles and games for children. The pictorial engravings were primarily featured on the journal’s cover, title page, and in these family sections. Many of them, in addition to being works of art, rather than epistemic illustrations, were didactic in a moral sense. In the engraving Prayer (fig. 51), for example, the depiction of a modestly dressed little girl, kneeling on the floor of a sparsely decorated interior with her hands clasped together in the lap of her mother, is positioned as an illustration of proper Christian behavior. “Surely this lovely picture needs no words of explanation or description,” the accompanying article begins, before launching into both an explanation and a description.[87] It discusses the engraving by printing extracts from John Ruskin’s criticism of the original painting (unnamed in the Agriculturist) by Pierre-Édouard Frère, when it was exhibited in the French Gallery in London in 1857. The journal quoted the renowned English critic’s praise of the painting, which centered on its moralizing nature: Ruskin writes that the daughter’s bare feet, resting upon the garment spread on the floor, were “as reverently and surely in God’s presence as if the poor cottage floor were the rock of Sinai,” or the mother’s “dear, bowed, patient face and hands folded” were “clasped in solemn awe, lest they should part or move before her Father’s blessing had been given in fullness.”[88] The painting, Ruskin concluded, stood as a paradigm of Christian life: “Return to it,” the Agriculturist quoted, “and still return. It should be the last picture you look at in all the year; carrying the memory of it with you far away through the silence of thatched villages and the voices of the blossoming field.” Judd seconded these sentiments, expressing the hope that there is “not one of our dear young readers, who lives a prayerless life . . . It is not childish to pray; it is noble, it is manly, it is Christ-like.” Prayer, then, served as an exemplary model of Christian behavior for young readers.

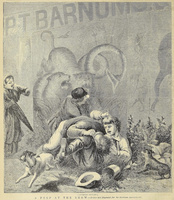

Moralizing commentary accompanied nearly all other pictorial engravings as well. In July 1873, the journal published William M. Cary’s A Peep at the Show (fig. 52), which, like Prayer, was used to teach proper comportment. At first glance, the engraving appears to depict two tigers and a large snake lunging at a pyramidal group of boys, huddled in fear near the bottom center of the composition. The middle boy, with a dark shirt, tucks his head into the lap of his seated, aghast-faced, white-shirted friend. Their exasperated dog darts away to the scene’s lower left with a look of abject terror, while another dog in the bottom right barks aggressively toward the looming animals. Meanwhile, an old, bonnet-clad woman enters the composition from the mid-left and gasps at the horrific scene unfolding in front of her. Yet, A Peep at the Show does not depict the moments before a ghastly tiger mauling. Upon closer inspection, the viewer notices the name “P. T. BARNUM” diagonally stretching across the upper register of the image and then realizes that the exotic animals are not real, but painted figures on a linen siding bordering the famous entertainer’s circus tent. Indeed, the cap-clad boy at the apex of the pyramid is not about to have his head consumed by the mouth of the rightward tiger but instead looks gleefully through a stark-white peephole at the circus inside; the tumble of the middle boy into the lap of his friend was seemingly caused by the push of this leftward boy to access the peephole. Cary’s composition deliberately misleads the viewer for humor’s sake—the shocked older woman and dogs represent the reader’s momentary belief that the tigers are real—but the reader is intended to eventually realize the fallacy of this initial presupposition and take pleasure in the playful and amusing engraving. Yet, the article accompanying A Peep at the Show once again establishes the correct instructional benefit of the engraving by lecturing on the “chaos” that results when young “rascals” try to circumvent societal rules—in this case, failing to properly buy admission to the show.[89] For Judd, the effort to “inculcate true artistic taste” extended beyond the skill of base artistic connoisseurship. More importantly, it meant that the reader would understand the moral lessons distilled from those images.

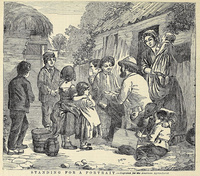

In order to ensure this visual comprehension, the Agriculturist’s pictorial engravings also encouraged the cultivation of artistic practice. In Standing for a Portrait (fig. 53), from August 1864, a group of young children and a young woman stand around an itinerant or amateur artist in a farmyard, while a young boy at the center has his portrait drawn. After pointing out the “moral countenance” of the model, the accompanying article discusses the act of art making.[90] While some individuals are born with talent, the article explains, everyone is capable of learning to serviceably draw with practice. “It is considered a disgrace not to be able to write,” it continues, “and the same pains taken in learning to draw would give equal success as in learning to use the pen”—even going so far as to claim that “such knowledge is of the greatest use, as by its descriptions can be given and facts preserved much better than by any use of words.” Similar justifications for the promotion of artistic practice accompany the engravings Taking Carlo’s Portrait (fig. 54) and The Young Photographer (fig. 55).[91] In all three articles, the Agriculturist frames drawing and artistic practice as a skill that had real merit to society in the United States. But, surprisingly, unlike the period’s numerous drawing manuals, which clearly linked the ability to draw to practical skills like increased perception and visual acuity, the Agriculturist offered no clear indication as to the nature of the specific benefit of artistic practice. This telling absence suggests that, for Judd, it was his normalization of artistic practice within US society that took primacy; a general sense of artistic enterprise, it is positioned, stands as an essential skill of the well-rounded citizen.

For Judd, the availability of artistic cultivation for all readers—rural or urban, rich or poor, young or old—became the guiding principle of his journal’s promotion of the arts. For example, an engraving titled First Effort (fig. 56) again shows that drawing was in everyone’s purview. A young boy, dressed in dark, baggy clothes, sits on a stool in the middle of a sparsely decorated interior, cheerfully smiling at the viewer while displaying a stick figure drawn in chalk upon a piece of slate. Judd writes that the simple figure is “not handsome to our eyes,” but he points out the boy’s happiness, calling him just as pleased with his drawing as “Benjamin West could be over one of his great paintings.”[92] The article informs the reader that the source of the boy’s pride is his act of original artistic creation, noting that the boy has “done it . . . all [on] his own.” The article continues to explain that the boy began by tracing forms from the book discarded at his feet, which—with its three barely discernable columns of text and a centered black horse standing in profile—bears a striking resemblance to the form of the Agriculturist. The self-reference is telling: the journal was capable of providing the visual spark that initiated the process of artistic discovery.

The mid-1870s once again brought hard times for the Agriculturist. The Panic of 1873 devastated all periodicals in the United States, and the farming journal’s subscriptions plummeted from a reported one hundred and sixty thousand in 1872 to ninety thousand in 1873 to only forty-five thousand in 1878. The rise of smaller, regionally focused farming journals also contributed to this decline in subscribers because they provided farmers with local alternatives that more specifically addressed the agricultural issues affecting a particular area. Faced with these financial challenges, Judd appears to have succumbed to the same misguided impulse as the Allens years before. Despite the precipitous drop in subscribers, the journal’s number of engravings markedly increased in volume 33 (1874) and beyond, with Judd spending more on engravings in the hopes of attracting new subscribers. Like with the Allens, the risky investment cost Judd his journal. He was forced to retire as editor in June 1878.[93] Control of the Agriculturist then passed to Judd’s brother, David W. Judd, and, upon his death in 1888, it was acquired by Herbert Myrick’s Phelps Publishing Company.[94] The agricultural journal continued to change hands throughout the twentieth century, eventually coming under the purview of Farm Progress, an agricultural publishing collective, where it is still currently issued in an online format.[95]

Negotiating the Agriculturist’s Position between Agriculture and Art ↵

Judd positioned the American Agriculturist as an illustrated agricultural journal that simultaneously provided instructional agricultural information, didactic engravings, and artistic depictions of US life aimed at “inculcat[ing] true artistic taste.” But, despite these rhetorical boasts, Judd did not intend for the Agriculturist itself to be considered art. Indeed, Judd developed both rhetorical and organizational strategies that situated the Agriculturist as art-adjacent, thereby allowing the periodical to maintain a delicate balance between the realms of practical agriculture and aesthetic art.

In June 1867, for example, the Agriculturist published a pictorial wood engraving titled The First Lesson (fig. 57). In the article accompanying the depiction of an older sister patiently teaching the alphabet to her begrudging younger sibling, the engraving was praised as “a specimen of art” not equaled or excelled by any journalistic picture published in the United States.[96] Yet, the article explicitly discouraged readers from tearing the picture out of the journal and hanging it on their walls. The engraving, the article explained, had advertising text printed on its verso that would eventually bleed through, thereby ruining the picture. Instead, the readers were encouraged to purchase a lithographic copy of The First Lesson, printed on “fine, heavy paper, fit for framing” and offered for sale by the Agriculturist’s parent company, Orange Judd & Co. Even though the two engraved pictures were nearly identical in composition and promoted the same lesson of hard work and study, the journal’s preference for the lithographic version demonstrates Judd’s adherence to the hierarchical standards of popular art in the United States.

For many middle-class homes throughout most of the nineteenth century, the most popular and appropriate forms of art and decoration were black-and-white or color (“chromo”) lithographs or copper engravings, either original compositions or, more often, reproductions of work of art. Writers like George W. Bethune advocated the edifying influence of such images, suggesting that houses that prominently displayed lithographs were characterized by a “neatness, temperance, and thrift.”[97] Similarly, Catherine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe, coeditors of the American Woman’s Home, extolled the virtues of lithographs as substitutes for paintings. When “well-selected and of the best class,” these women reasoned, lithographs became instrumental building blocks of the harmonious Christian household.[98] The Agriculturist, accordingly, echoed these writers by regularly positioning well-made prints as ideal decorations for the ideal home: “A bare wall is very cheerless,” Judd wrote in 1869,

Even the coarse colored lithographs that are hawked about are better than nothing to put upon the walls for the eyes to rest upon, but a well-executed engraving is much better. The introduction of Chromo Lithographs, or chromos as they are now popularly called, has placed it within the power of persons of moderate means to adorn their dwellings with beautiful pictures. Only the wealthy can afford to have original pictures, but almost every one can have the next best thing to them,—a good copy in chromo.[99]

In adhering to the populism promised by the lithograph and chromo, Judd signals his belief that the lithograph and chromo represented the most appropriate form of art for middle-class households. But, importantly, the engravings within the Agriculturist ostensibly did not meet the appropriate material standards put forth by these cultural commentators. It is implied that the Agriculturist’s engravings—like its version of The First Lesson—could be “artistic,” but only the lithographic renditions could be “art.”