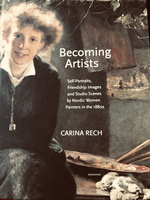

Becoming Artists: Self-Portraits, Friendship Images and Studio Scenes by Nordic Women Painters in the 1880s by Carina Rech

Reviewed by Alice M. Rudy PriceAlice M. Rudy Price

Adjunct Instructor,

Temple University, Tyler School of Art

alice.price[at]Temple.edu

Citation: Alice M. Rudy Price, book review of Becoming Artists: Self-Portraits, Friendship Images and Studio Scenes by Nordic Women Painters in the 1880s by Carina Rech, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 20, no. 3 (Autumn 2021), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2021.20.3.18.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Carina Rech,

Becoming Artists: Self-Portraits, Friendship Images and Studio Scenes by Nordic Women Painters in the 1880s.

Göteborg and Stockholm: Makadam Förlag, 2021.

448 pp.; 64 color and 28 b&w illus.; bibliography, notes, index of names, and 6 pp. summary in Swedish.

326 kr [about $38 USD] hardcover; free open-access PDF at diva-portal.org.

ISBN 978–91–7061–354–80

Carina Rech’s Becoming Artists integrates thoughtful and probing epistolary analysis and careful observation of select self-portraits, paintings of artists’ studios, and friendship paintings to interrogate how a pioneering generation of Nordic women painters fashioned their roles as worker-artists using emulation, collaboration, and appropriation. Through her narrow focus on a handful of mostly Swedish middle-class painters and sculptors active in the 1880s, Rech ably examines women’s networks, studios, travels, and personal and professional artistic development. Her analysis of paintings and letters as evidence of self-fashioning benefits from her access to previously unpublished archives and new acquisitions of works by women made by major Nordic cultural institutions. Makadam published this book in 2021, concurrent with Rech’s defense of the project as her dissertation at Stockholms universitet. The book’s publication is timely in that it also coincides with relevant exhibitions, including the forthcoming Hirschsprung Collection retrospective on Bertha Wegmann.[1]

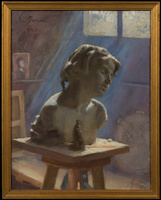

In her introduction, Rech summarizes her project: “In short, this book is about women who used painting to stage interventions into the representation of the artist” (14). Furthermore, the author asserts that the visualized connections between the women elucidate a strategic network eclipsed or erased in extant monographs, collective exhibitions, and theoretical approaches. Rech structures each section on exemplars of “painterly self-fashioning,” with extended analysis of seven paintings over three chapters. Chapter 1, “The Self-Portrait,” centers on Swedish expatriate Julia Beck’s 1880 painting executed and exhibited in Paris. Chapter 2, “The Friendship Image,” explores the paintings by Dane Bertha Wegmann of Swede Jeanna Bauck, including the 1881 example featured on the book cover (fig. 1), a later portrait from 1885, and a situational scene by Bauck depicting Wegmann painting a portrait (1889). Rech anchors the final chapter, “The Studio Scene,” on Hanna Hirsch-Pauli’s painting of The Artist Venny Soldan-Brofeldt (1886–87, fig. 2), which Rech furthermore concludes “unites all the central concerns” of the book (267). Rech supplements the atelier focus with comparative analysis of Swede Eva Bonnier’s studio interior (1886) and Norwegian Asta Nørregaard’s 1883 self-portrait.[2]

Rech’s introduction provides brief biographies of the principal artists and identifies points of intersection in their careers. Rech includes a good historiographic essay in which the author clearly positions the current project. Her argument builds from Oskar Bätschmann’s theory of the exhibition artist; gender, queer, and Scandinavian specialists; as well as cultural historians and philosophers who theorize performance and spatial environment as related to the body.[3]

Rech’s first chapter conceptualizes the manipulation of form, subject, and genre by Nordic women artists in the 1880s to construct a professional and social image “in relation to her contemporary audience and in relation to a pictorial tradition” (65). Rech carefully dissects visual evidence, including costume and subject matter. The author demonstrates that the composition and style of Beck’s self-portrait, her Salon debut, paid homage to canonical painters who were popular at the end of the nineteenth century, including Diego Velázquez and Rembrandt van Rijn (69–72). Beck’s visual expression of admiration for these seventeenth-century painters aligned with that of emerging Nordic artists, such as Ernst Josephson and Hugo Birger (77–79). Rech meticulously unpacks divergent audiences and conflicting goals for Beck’s self-portrait. As an exhibition artist, Beck had to balance Nordic middle-class expectations that a woman would be modest with a working artist’s incompatible necessity to self-promote. Additionally, of the women studied, only Beck, who settled in the French art colony Grez-sur-Loing after 1882, was “an outsider caught in between two national historiographies, the Swedish and the French” (98). Previously unpublished letters demonstrate that much later, at the end of her career, Beck would utilize the same self-portrait to solidify her artistic legacy. As Rech explains, the artist’s donation of the self-portrait to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm fifty years later was a deliberate move to “counteract her marginalization” (99).

“The Friendship Image” significantly extends current scholarship on Wegmann and this pioneering generation of women artists. Rech investigates these artists’ strategic use of friendship images, mining previously unpublished letters between Wegmann, Bauck, and their colleague Hildegard Thorell. The integration of textual and visual evidence helpfully illuminates the dynamics of professional practice and personal relationships as the women physically age and vocationally mature. Rech perceptively theorizes how works by Bauck and Wegmann compare to friendship images in partnerships such as that between Norwegians Kitty Kielland and Harriet Backer. Careful observation provides the chapter’s foundation. Rech delves into various aspects of Wegmann’s 1881 portrait of Bauck: the informality of a woman sitting on a table and leaning toward the beholder/viewer; the light that seems to radiate from within and reflect the daylight of the studio windows; the mingled attributes of painting and reading. Rech interrogates the historical significance, critical legacy, and gendered context of each of these.

Rech argues that the tight-knit friendship circles of the women she studies were different from artistic brotherhoods; they were “more interpersonal, informal and pragmatic, rendering emotional community” (118). She characterizes the relationship between Wegmann and Bauck as “based on affection, identification and at times even co-dependence” that “basically excluded the rest of the world” (130). Their intimacy was complicated when Wegmann entered into a new cohabitation with a younger partner, Toni Müller, who cared for Wegmann until the end of the artist’s life. Rech cautions that despite the emotional tone of the correspondence, contemporary readers cannot determine whether “these women engaged in any sexual intimacy.” Like other women of their generation, they faced dangers to their “reputation and respectability” and so were “discreet . . . about physical desire” (135). Rech concludes that if partnerships like that between Bauck and Wegmann were not necessarily sexual, they certainly provided necessary emotional, financial, and professional support generally denied to married women (138). The conclusion to the book cautions that such relationships do not fit neatly into current classification. “These were queer relationships in the sense that they cannot be grasped by hetero-versus homosexual categorizations” (271).

The author effectively contrasts the 1881 and 1885 portraits of Bauck by Wegmann using epistolary evidence from Thorell and Wegmann. Their letters expressly differentiate the reception of the 1881 portrait in France from that in Denmark. Critics and visitors to the Paris Salon praised the portrait of Bauck. However, in Copenhagen, Wegmann’s home, the situation was the reverse. Wegmann complained of Danish “philistinism” and that “no one comprehends one whit of my painting” (169). Rech interprets the 1885 portrait’s more formal posture as a rejoinder to Copenhagen’s conservative backlash against the 1881 portrait at the annual Salon. Yet Rech emphasizes that each painting draws attention to the professional partnership.

In discussing Bauck’s double portrait, The Danish Artist Bertha Wegmann Painting a Portrait (1889; fig. 3), Rech dissects the structure of the painting, which has Wegmann’s unfinished canvas at the compositional center. Rech writes:

In fact, what the beholder sees on the canvas in the center of the composition is not the portrait of Dethlefsen, but rather Wegmann’s head, which is framed by her own canvas, as she blocks the likeness she is working on from view. From the beholder’s perspective, Wegmann thus becomes a portrait head on her own canvas, which turns the scene into a mediated self-representation painted by her artist friend Bauck (149).

Rech elucidates the entangled artistic identities in the double portrait (150). The author’s probing conclusion of the degree and quality of professional cooperation is especially provocative. Bauck reminisced in 1924 that when she shared the same studio space with Wegmann, she used to “paint the clothes, the background, and the details in [Wegmann’s] portraits” (186). Furthermore, according to Müller, Wegmann liked to paint hands and in several instances executed this detail in Bauck’s paintings (187). Rech likens the collaboration to traditional early modern workshops, while also emphasizing how unusual their practice was: “The purposeful pragmatism of the artists’ productive collaboration runs contrary to the widespread understanding of the modern artist as autonomous, independent, self-contained and creating original work” (187–88).

The final chapter considers depictions of artists’ studio interiors as akin to self-portraits that express professional ambitions and social identity. The analyses of Hirsch-Pauli’s Portrait of Venny Soldan-Brofeldt (fig. 2) and Eva Bonnier’s Interior of a Studio in Paris (1886; fig. 4) deftly interweave issues of studio culture, gendered spaces, artistic rivalry, agency, and style. The historian draws on both studies of studio culture (217–29) and of paragone (240–55) to scaffold her conclusions. To bolster the visual and epistolary evidence, she also assesses sketches and descriptions of studio spaces by other women artists found in letters and albums from study trips to Paris and Munich. Hirsch-Pauli and Bonnier both depict their studios as sparsely decorated workspaces dedicated to the physical work of making art, in contrast to lavishly decorated show studio examples preferred by many male contemporaries.[4] The women thereby identified with the working classes. For example, Rech elucidates how Hirsch-Pauli and Bonnier each lived intentionally frugal lives, emulating male worker-artists, and suppressing their own bourgeois backgrounds.

Rech then turns to the Pygmalion myth to elucidate professional and gender issues, comparing contemporary French and Nordic interpretations of the myth by male painters, including Jean-Léon Gérôme (1890), Édouard Dantan (1887), and Carl Larsson (1888–89). This excursion away from her core subject allows her to contrast the varying use of the myth by men and women. In Interior of a Studio, Paris, Bonnier makes the sculpture the focal point of the painting and substitutes the studio for the body of the artist, suggesting that it made the sculpture. In sharp distinction from the versions done by male painters, the viewer/beholder does not see a female body as primarily a sculpted object or an artist’s subject. Bonnier emphasizes instead what she has made: a bust rather than a nude. Rech observes furthermore that in Portrait of Venny Soldan-Brofeldt, Hirsch-Pauli handles the theme more dramatically than Bonnier:

. . . literally takes sculpture down from its pedestal and lets it sit on the wooden floor of a humble studio. This is a radical move given the traditional role of woman as the artist’s model and the female body as the subject for sculpture. Soldan’s pose is not only provocative in the sense that it counteracts feminine decorum by appropriating the ideal of the worker-artist, it is also unusually proprietorial in the sense that it stages an act of appropriation of the studio as a professional space and hence turns Soldan into the creator of the sculpture (251–52).

These musings on Pygmalion appropriately set up a discussion about agency in the portraits and studio paintings. Whereas Hirsch-Pauli earned positive acclaim when the painting was exhibited at the Salon, the sitter, Soldan-Brofeldt, shouldered the burden of public censure in Helsinki, where the painting was subsequently exhibited (252–53). Rech queries, “[W]ho bore the main responsibility for the friendship image: the artist who painted or the artist who posed?” (254). Whereas the friendship portraits may convey “emotional support” through their “naturalistic portrayal” within the artists’ sisterhoods, Nordic audiences perceived such depictions as threats to the norms of middle-class decorum, and hence to the affluent bourgeois public most likely to purchase or to commission works of art (255).

Under the subheading “the Self-Portrait Extended into Space” Rech reprises her 2018 article in Kunst og Kultur on Asta Nordgaard’s In the Studio (1883), which uses the studio to provide a professional resumé at a pivotal point in the artist’s career.[5] At the time, Nørregaard was working on the altarpiece for the Gjøvik church, noteworthy for it being the first religious commission offered to a woman in Norway. Furthermore, In the Studio mixes genres and styles: the altarpiece uses the licked surface touted by academies, the still-life is executed in a trompe l’oeil manner, and an impressionist-style plein-air landscape is framed by the mullions of the atelier’s clerestory. The artist is positioned at the compositional center, in command of the depicted Parisian studio, armed with a carefully arranged palette and all the professional tools required by her work. Rech summarizes, “The painting thereby turns into a painted manifesto and a carte de visite advertising its maker. Ultimately Nørregaard’s self-portrait is not about self-questioning, but about self-presentation” (260).

Rech’s focused and in-depth study on a specific decade within a narrow geographic region extends English-language scholarship on several important artists. Moreover, her focus on a “conspicuous occupational group” (267) identifies the unique, gendered strategies used by women to fashion their careers and promote their art. The visual, epistolary, and archival evidence is compelling and suggests future areas of research, whether in different generations or different geographic regions. Rech relates the studio practice of artists in the 1880s to Virginia Woolf’s “room of one’s own,” a book that was published forty years later (267–68). The comparison is more provocative than applicable, suggesting possibilities to analyze similarly the self-mediation strategies of subsequent generations in a variety of media. And although Rech restates in the conclusion three shared practices–emulation, collaboration, and appropriation—that labeling system oversimplifies the rich findings in the book.

Rech’s volume invites the reader into the lives and experiences of the women. One encounters specific personalities, relationships, and struggles. These details about individuals and small friendship groups sometimes obscure the overall circumstances of Nordic women who hail from distinct and specific Nordic places. Although Rech summarizes the education and exhibition opportunities for women in Stockholm in chapter 1, the different gendered cultural milieus of Copenhagen, Oslo, and Helsinki are not as clear. The reader would benefit from a direct explanation of how women from distinct national and linguistic groups fostered a collective “Nordic” bond. The artists’ Nordic identity functions to limit Rech’s sample set rather than to reference ways that Nordic-ness may have impacted how or why these women adopted particular strategies as exhibiting artists. The Scandinavian context might have been particularized by a more nuanced account of how its gender conventions differ from other periods and places (e.g., Scandinavia vs. France). Given that most of the artists in the study are Swedish, it is surprising not to find any reference to local feminists such as Ellen Key. To contextualize the letters and the images, the positions of middle-class women in the respective countries and their regional opportunities for work, education, and independence could be fleshed out more fully.

Like many books that derive from dissertations, On Becoming Artists could benefit from another round of editing. A dissertation’s function as a demonstration of proficiency for a degree often results in extended expositions of theoretical underpinnings. Similarly, while dissertations are obliged to provide a complete account of the historiography, in a book some of this might be relegated to the notes, condensed, or omitted. At the same time, Rech is to be commended for her extremely clear historiographic synopses and for clearly situating her own arguments in relation to the existing literature. The structure of the book is apparent, but its transitions are sometimes laborious. Signposts like “In the following . . . will be outlined” (72) detract from the generally elegant prose and argument and make the book longer than necessary.

Rech’s division of the body of the text into only three chapters corresponds to her methodology but taxes the reader. Subtitles signal focused sections. However, some of the comparisons and key findings get buried under piles of evidence. Each chapter is more like a short book. For instance, “The Friendship Image” is over one-hundred pages and could easily be broken into two or three chapters. Such a division might help some of the lesser-known works of art or artists emerge as more fully formed.

Makadam has published a clean, well-proportioned book that is effectively laid out. Becoming Artists includes many full-page and half-page color illustrations of works that are little known in the United States and often outside the canon of even the home countries of the artists. As many of the discussed paintings are unfamiliar to English-speaking audiences, it would have been helpful to have more complete captions that included the collection, medium, and size. This information, however, can be found in the list of illustrations. The reproductions are mostly high quality, and the reader can almost always locate the relevant details from Rech’s argument. The high-resolution reproductions of letters, pages out of albums, and photographs support the text excellently. The documentation might be more useful if divided by chapter or page range instead of the consecutive numbering of one-hundred pages of endnotes that numbered over one thousand.

Rech should be commended for an excellent volume that fills a void in the literature. The book will be useful to scholars of Scandinavian art, gender, the juste-milieu, and modernism. I look forward to future contributions from this emerging scholar.

Notes

Translations from Nordic languages are by Carina Rech.

[1] Bertha Wegmann. The Hirschsprung Collection, Copenhagen. February 16–May 22, 2022, https://www.hirschsprung.dk/en/udstillinger/udstilling-bertha-wegmann.

[2] Although Rech meticulously uses the maiden names (Hanna Hirsch, Venny Soldan) for works executed prior to the artists’ marriages, for clarity in this much shorter review, I use only the hyphenated names they used professionally for the rest of their career.

[3] See Oskar Bätschmann, The Artist in the Modern World: The Conflict Between Market and Self-Expression (Cologne: Dumont, 1997); Rech divides the methodological section between “Theories and Methods” (34–54) and “Previous Research” (54–62).

[4] Rech interprets the studio interior as a self-portrait and distinguishes the working studio from the show studio based on Rachel Esner, “At Home: Visiting the Artist’s Studio in the Nineteenth-Century French Illustrated Press,” in The Mediatization of the Artist, ed. Rachel Esner and Sandra Kisters (Cham: Spring International Publishing, 2018), 15–30.

[5] Carina Rech, “Revisiting Asta Nørregaard in the Studio,” Kunst og Kultur, 101 (2018): 1–2, https://www.idunn.no/kk/2018/01-02/revisiting_asta_noerregaard_in_the_studio.