Three Books about Elizabeth Siddall’s Poetry

Reviewed by Deborah CherryDeborah Cherry

Professor of Art History and Theory

Central Saint Martins

University of the Arts London

deborah.cherry[at]arts.ac.uk

Citation: Deborah Cherry, book review of Three Books about Elizabeth Siddall’s Poetry, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 20, no. 3 (Autumn 2021), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2021.20.3.11.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Serena Trowbridge, ed.,

My Lady’s Soul: The Poems of Elizabeth Eleanor Siddall.

Brighton: Victorian Secrets, 2018.

122pp.; 6 b&w illus.; notes; appendices.

$14 (paperback)

ISBN 978–1–906469–62–7

Anne Woolley,

The Poems of Elizabeth Siddal in Context.

Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021.

284 pp.; 20 b&w illus.; bibliography; notes; index.

$120 (hardcover)

ISBN 978–1–5261–4384-6

Stephania Arcara, ed. and trans.,

Elizabeth Siddal: Di rivi e gigli: poesie e lettere (Elizabeth Siddal: Of Rivers and Lilies: Poetry and Letters).

Bari: Palomar, 2009.

130 pp.; 4 b&w illus.; notes.

Free open access PDF at Academia.edu

ISBN 978–88–7600–315–8

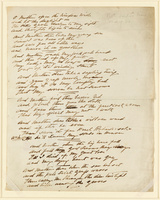

Elizabeth Siddall is reading, drawing, posing, and reposing in surviving drawings of her (fig. 1); she is not portrayed writing, pen or pencil in hand.[1] Known as a model and muse to Pre-Raphaelite painters, Siddall was a poet as well as an artist.[2] A small collection of her poetic manuscripts is held in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (fig. 2),[3] along with fair copies by both Rossetti brothers. Siddall’s poems were released piecemeal by William Michael at the fin-de-siècle. The first collection, judiciously edited by Roger C. Lewis and Mark Samuels Lasner in 1978, has now been followed by two new editions.[4] While all agree on a corpus of some fifteen poems, Serena Trowbridge’s My Lady’s Soul: The Poems of Elizabeth Siddall also includes surviving verse fragments.[5] Trowbridge elucidates Siddall as an artist and a poet and outlines the publication history and reception. She emphasizes the clarity and forthrightness of Siddall’s voice, that of “a woman who knows what it is to be valued only for her appearance, as a woman who has to fight to be taken seriously” (14). For each poem she provides line-by-line annotation, enlightening comparison, and commentary. She disposes of the titles invented by William Michael Rossetti. In this review I follow her use of the first line, adding the more familiar title in parentheses. Stephania Arcara’s Di rivi e gigli: poesie e lettere introduces Siddall’s poetry and responses in Italian and English. Arcara uncovers “a surprisingly vigorous poetic voice, vibrant with anger and contempt” resistant to yet isolated by the failures of romantic love (33). Her spirited feminist analysis concludes that the thematic core of Siddall’s literary corpus is “an articulate and passionate meditation on feminine desire, a poetic investigation of the restless soul of a woman who loved and was loved” (37).[6] Writing in Italian, Arcara includes parallel translations of the poems and letters. The inclusion of Siddall’s surviving letters (six in Arcara, two in Trowbridge) is a reminder of how often Siddall has been spoken for in Pre-Raphaelite diaries, letters, and memoirs.

In Anne Woolley’s The Poems of Elizabeth Siddall in Context, the first book on Siddall’s poetry, the “contexts” include, first, Siddall’s art, each chapter opening with an illuminating discussion of one or two artworks; second, her life and death, with biography a constant point of reference; and third, literary comparisons to “some of the most illustrious nineteenth-century male poets” (263) with concise discussion of women writers. Comparison to Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s The House of Life (final version 1881) highlights attitudes to love, desire, and beauty; a focus on Algernon Charles Swinburne shapes an investigation of the ballad revival; the social position of women is explored in relation to Alfred Tennyson’s “The Princess” (1847) and John Ruskin’s “Of Queens’ Gardens” (1865) alongside Siddall’s encounters with mid-century feminists and the drawings they made of her; a chapter on John Keats traces specters and hauntings. In a fascinating account Woolley considers that Siddall’s poetic output is marked by dualism and paradox, ambiguity and elusiveness, caught between the spectral and the earthly, divine and human love, voice and mutedness, autonomy and restraint. The risk is that Siddall’s slight oeuvre may be overwhelmed and outpaced, especially when, as here, her poems are summarized with inline quotation rather than quoted in extended offset. Although publishing after Arcara and Trowbridge, Woolley follows the 1978 edition. The images on the book covers testify to the interlacing of art, life, and poetry: respectively, Anna Mary Howitt, Elizabeth Siddall, 1854 (Mark Samuels Lasner collection, University of Delaware Library), Elizabeth Siddall, Pippa Passes, 1854 (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford), and Elizabeth Siddall, Self-Portrait, 1853–4 (private collection).

Arcara and Trowbridge elucidate Siddall’s prosody, revealing a poet attentive to structure and form, sound and word play, imagery and tone, the art of the line. Siddall wrote poems with three, four, and six line stanzas, varying the rhythms, line lengths, and metrics and playing with internal rhymes, multiple valances, alliteration, and repetition. Trowbridge emphasizes that deceptive simplicity occludes internal complexity (14). Siddall’s poems participated in the ballad revival; she was an avid reader and attentive student of Romantic poetry, Border ballads, and contemporary poetry. Literary parallels featured in these publications reveal the connections and exchanges between the poetry she read, the poetry she wrote, and the visual images she made. Her poetry, like that of her contemporaries, was textured in a dense web of echo, reprise, and citation, an intertextuality that Antony H. Harrison identifies as characteristic of the mid-century medievalizing Siddall favored.[7]

In her writing and her art, Siddall focused on emotionally charged moments. Her studies for Jephthah’s Daughter test different configurations for the two principals to convey their mutual recognition that to honor the father’s vow to God, the daughter must be sacrificed (fig. 3). In Clerk Saunders (1857), inspired by the ballad of the same name from Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, Margaret confronts the ghost of her departed lover.[8] Lady Clare (1857), its subject from Tennyson’s Poems (1842), portrays a daughter’s challenge to her mother about her birth. The interiors, with their multiple openings and levels, intensify the drama. Markers of time, place, and location are sparse in the poems—a graveyard, a wood, a room with a window. While mood-enhancing settings draw on the writer’s engagement with the natural world (Trowbridge, 14), the imagery of lilies and rivers and angels comes, I suspect, from poetry and pre-modern art. Whereas Siddall’s watercolors are realized with bold blocks of strong color, her poetic palette is restrained, with rare bursts of vivid red, green, and blue. Her poetic world is animated with the metonymic body parts of Romantic poetry—hands, face, eyes (Trowbridge, 16); with sound—singing, the “clang” of birds, wild and sighing winds; touch and sensory experience; and contrasts of light and shadow in which light signifies Christian revelation and daylight while shadow is a cast shape (“Take thou thy shadow from my path,” quoted below), a darkened wood, a departed soul.

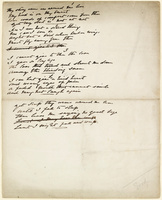

Trowbridge’s suggestion to read Siddall’s poems aloud offers an interpretative route lightly touched on in these volumes and worthy of further consideration (37). Siddall’s poems are stages for varied protagonists with distinctive voices who offer elegiac reflections on grief and loss, gentle counsel, loving care, wistful regret, imperious declaration, and what Christina Rossetti identified as “a cool bitter sarcasm.”[9] Siddall’s poems are performative, declarative, and interlocutory, sharing some of the characteristics of the dramatic monologue, a poetic form that relies on the separation of poet and protagonist.[10] In “O mother open the window wide” (“At last,”) a mother consigns her son and her death rituals to her own mother’s care (fig. 2).[11] More often, Siddall relishes an indeterminacy for her speakers who, unlike the characters delineated in dramatic monologues, are not named or historically situated. In an absorbing analysis of “Oh never weep for love that’s dead” (“Dead love,”) the poem so admired by Christina Rossetti, Carol Rumens proposed in 2015 “[t]he speaker is perhaps a mother, advising a listener who is perhaps her daughter,” though “it’s not impossible to imagine a male addressee.” For Rumens, repetition and metrical informality “help to dramatize the poem as speech,” one of “murmured but impassioned assertion.”[12] Siddall’s speakers hail unidentified and undecidable counterparts; even when affectionately construed, little is disclosed as to whether the addressee is present, can hear, or is listening.

Oh never weep for love that’s dead

Since love is seldom true

But changes his fashion from blue to red

From brightest red to blue

And love was born to an early death

And is so seldom true.

Then harbour no smile on your bonny face

To win the deepest sigh

The fairest words on truest lips

Pass on and surely die

And you will stand alone my dear

When wintry winds draw nigh

Sweet, never weep for what cannot be,

For this God has not given

If the merest dream of love were true

Then, sweet, we should be in Heaven,

And this is only earth my dear

Where true love is not given (Trowbridge, 76)

This is one of five poems to begin with “O” or “Oh.” An exclamation, invocation, solicitation, recognition, O/Oh carries into these poems what Gabe Rivin identifies as its “unique emotional color—a yearning, and a kind of rapturous crying out.”[13] For poet Laurence Goldstein, O announces a text “spoken by poets’ characters, not in the voices of poets themselves,” appearing when poets adopt a “mask or persona.”[14] Some of Shakespeare’s most famous soliloquys begin with O, and Siddall may have used this literary device to signal her poems are speeches.

In the title poem of Trowbridge’s edition, (also known as “The lust of the eyes”) a masculine protagonist dissects the power relations and ocular pleasures of masculine desire in a vociferous refutation of the conventions of courtly and romantic love and the prizing of woman for her appearance.

I care not for my Ladys soul

Though I worship before her smile

I care not wheres my Ladys goal

When her beauty shall [lose its wile.]

Low sit I down at my Ladys feet

Gazing through her wild eyes

Smiling to think how my love will fleet

When their starlike beauty dies

I care not if my Lady pray

To our Father which art in Heaven

Though for joy in my heart wild pulses play

For to me her love is given

Then who shall close my Lady’s eyes

And who shall fold her hands?

Will any hearken if she cries

Up to the unknown lands? (Trowbridge, 36)

The poem enacts a skillful doubling, voicing the woman poet’s appropriation of a masculine voice. The speaker scorns and sneers, mocking the lady’s transient beauty and deriding her “soul,” connoting at once her inner life and her afterlife, her piety and her spiritual existence after death. “Ope not thy lips thou foolish one” (“Love and hate”) stages an escalating see-sawing tension between the speaker and the anticipated actions of the addressee. The protagonist issues a series of vehement injunctions—be silent, stop asking,[15] look away, go away, and stay away—to one she views as a destructive force.

1

Ope not thy lips thou foolish one

Nor turn to me thy face

The blasts of heaven shall strike thee down

ere I will give thee grace

2

Take thou thy shadow from my path,

Nor turn to me and pray

The wild wild winds thy dirge may sing

Ere I will bid thee stay

3

Lift thy false brow from the dust

Nor wild thy hands entwine

among the golden summer leaves

To mock the gay sunshine

And turn away thy false dark eyes

Nor gaze upon my face

great love I bore thee now great hate

Sits grimly in its place

All changes pass me like a dream,

I neither sing nor pray

and thou art like the poisonous tree

that stole my life away (Trowbridge, 80)

Arcara highlights the adroit use of anaphora to heighten the poem’s expressive power and intensify the “apocalyptic ferocity with which the woman hurls her curses at the beloved”(41).[16] In a perceptive analysis of Siddall’s poetry published in the late 1990s, Constance Hassett takes line 14 as the core of the poem to highlight its contradiction between “a speaker disinclined to use words and the artist who makes a poem out of rhymed ballad stanzas.” While this poem “flaunts its own outspokenness,” she notes that elsewhere Siddall takes up “the challenge of representing withheld speech and even muteness,” finding in ballads “ways to write of what her speakers do or cannot say.”[17] This point is echoed by Woolley in her discussion of what she identifies as a “fractured female voice” (110–13).

Siddall’s protagonists contemplate the state of the heart, a poetic concern beautifully realized in Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “My Heart and I” (1862). With homophony and alliteration, Siddall lyrically captures the joy when “Love floated on the mists of morn” (Trowbridge, 63). She also creates striking images of violent shock when “love turned and struck me down / Amid the blinding snow” (Trowbridge, 86) (fig. 4). Read together, the poems yield probing investigations of loss, grief, and memory. “Many a mile over land and sea” (“Speechless”) recalls a traumatic moment when hearing, memory, and speech failed, when an unsolicited meeting provoked aphonia and amnesia: “I remember not the words he said,” “. . . words came slowly one by one / from frozen lips shut still and dumb” (Trowbridge, 57). Only the senses remain in memory—the touch of chill wind, the sound of sighing trees, the stench of mold. The speaker is reduced to a state akin to “living death.” Elsewhere, emotional exhaustion is likened to “beaten corn of grain” (Trowbridge, 43). To read Siddall’s poetic practice as performative is to concede a conceptual differentiation between the I who writes and the I who lives. In 1878 the poet Augusta Webster advised her readers of this separation in her essay “Poets and Personal Pronouns,” writing “as a rule, I does not mean I.”[18] More recently Zadie Smith has identified the gap between “the ‘I-who-is- not-me’ of the writer” and “the ‘I-whom-I-presume-is-you’ that the reader feels they can see,” an insight that perfectly captures the persistent slippage between Siddall’s life and art. Smith explains that in first person writing “you [the writer] take on an impossible identity, someone you can’t be, because you are already you—and not this ‘I’ in the book.”[19]

Siddall’s poetry, like Tennyson’s, was enmeshed in Christian reference with quotation, echoes, phrasing, and imagery drawn from the King James Bible and from recent hymns, as in her vision of heaven as “unknown land/s” or the anaphoric variation in “Life and night are falling” (“Lord may I come.”)[20] Somewhere between a devotional poem, a hymn, and a prayer, this poem dwells on mid-century anxieties besetting Christian faith. Christian subjects, including the Madonna and Child, the Nativity, winged angels, and Jephthah’s Daughter (from Judges 11 and Tennyson’s “A Dream of Fair Women” in Poems, 1842), feature in Siddall’s art (fig. 3). In a chapter on her exquisite watercolor, St Agnes’ Eve, Trowbridge has written compellingly of the artist’s visual representation of Christian piety.[21] Trowbridge and Hassett, both scholars of Christina Rossetti, share with Arcara an attention to the correspondences between the two women poets, including their preference for divine love over human love.

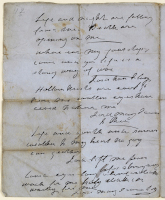

Siddall wrote on small-size off-white or blue unlined folded paper of a kind commonly used for letter-writing: pages are creased, torn, and chipped, some no more than scraps. Like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, she revised verses and sequences; unlike him, it seems she had no bound notebooks with lined paper in which to draft, edit, and preserve her writing. Similarly, as far as is known, she owned no bound artist’s sketchbooks of the kind used by her contemporary, the artist Joanna Mary Boyce, and now in the British Museum. Siddall’s cursive can be challenging to decipher, at times almost illegible (fig. 5). While some pages are assured with few changes or redaction (fig. 4), on others, words and phrases are squashed against the margins, written cross-wise, out of line, and scored out. The initials “E.E.R” on her fair copy of “True Love” indicate the months between her marriage in May 1860 and her death in February 1862.[22] The sheets are undated, making it impossible to establish chronology or artistic trajectory. Siddall left no authorized texts: her poems were not published in her lifetime.[23]

Arcara and Trowbridge adjudicate, with different outcomes, between Siddall’s manuscripts, Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s 1865 fair copies of six poems, and William Michael Rossetti’s autograph and published versions. While she has carefully consulted the manuscripts, Arcara exerts a level of editorial consistency in line with earlier editors. Trowbridge closely follows Siddall’s texts. She considers that “the previously published versions are poems created by William Michael Rossetti from the fragments available to him” (17); he “tidied up” (53), inserted punctuation, changed and sometimes added words such as those in square brackets in line 4 of “I care not . . .” (36). In transcribing and assembling numerous variants she acknowledges the occasional difficulty of arriving at a conclusive version. For Siddall’s best-known poem Trowbridge selects not the well-known text compiled by W. M. Rossetti, “A year and a day,” preferring instead “the most complete MS of this poem in Siddall’s handwriting,” four stanzas beginning “It is not now a longing year” (41).[24] She restores lines to “Many a mile . . .” and “O Silent Wood . . .” and stanza breaks to give clarity. In “O God forgive me that I ranged” (“The passing of love”), she follows Siddall’s stanza order, ending the poem on an upbeat (63–65).

Siddall’s poems have been judged unworthy of serious consideration: too personal, too sad, or as her brother-in-law opined “restricted in both quantity and development.”[25] Recent reappraisal disagrees. For Carol Rumans, Siddall’s “stripped-down, direct, emotionally intense” poetry was written by “a conscious craftswoman, aware of voice, form and characterization.”[26] These three publications acknowledge Siddall’s poetry as poetry, produced in conversation with texts by her predecessors and contemporaries, literary outputs worthy of scholarly attention. Changing the horizon grants Siddall an autonomous poetic voice, one that is recognizably, as Zadie Smith puts it so succinctly, “the-I-who-is-not-me.”[27]

Notes

[1] Virginia Surtees, Rossetti’s Portraits of Elizabeth Siddal: A Catalogue of Drawings and Watercolours (London: Scolar Press, 1991). I retain her family name, Siddall.

[2] For her artworks see Jan Marsh, Elizabeth Siddal: Pre-Raphaelite Artist, 1829–62, exh. cat. (Sheffield: Ruskin Gallery, 1991).

[3] John Bryson collection, WA1977.182. Some are available online, for example, https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/799472. Warmest thanks to Caroline Palmer, Ashmolean Print Room, for exhilarating discussion and access to the manuscripts and to Amy Taylor at the Ashmolean Picture Library for facilitating the images.

[4] Poems and Drawings of Elizabeth Siddal, ed. Roger C. Lewis and Mark Samuels Lasner (Wolfville: Wombat Press, 1978). This is the source for selected poems published in Marsh, Elizabeth Siddal, 1991, where she replaces lines 11–12 of “I care not . . .” with the 2 closing lines from “O Mother . . .” (34).

[5] It is not known whether Siddall wrote other poems for which the manuscripts are now lost. By 1903 W.M. Rossetti had identified the 15 poems included in all three collected editions: “The amount of verse which she produced was, I take it, very small; certainly what remains in my hands is scanty.” W. M. Rossetti, Dante Rossetti, and Harold Hartley, “Dante Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddal,” Burlington Magazine 1, no. 3 (1903): 291, https://www.jstor.org/stable/855671 [login required].

[6] “una voce poetica sorprendentemente vigorosa, vibrante di rabbia e disprezzo”; “il nucleo tematico della sua produzione è costituito, a mio avviso, da una articolata e appassionata meditazione sul desiderio femminile, una indagine poetica sull’animo irrequieto di una donna che ha amato ed è stata amata.” All translations by the author. See also, Stephania Arcara, “Sleep and Liberation: The Opiate World of Elizabeth Siddal,” in Sleeping Beauties in Victorian Britain: Cultural, Literary and Artistic Explorations of a Myth, ed. Beatrice Laurent (Bern: Peter Lang, 2014), 95–120.

[7] Antony H. Harrison, “Arthurian Poetry and Medievalism,” in A Companion to Victorian Poetry, ed. Richard Cronin, Alison Chapman, and Antony H. Harrison (Oxford: Blackwell, 2002), accessed July 29, 2021, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9780470693537.

[8] Siddall owned volumes 3 and 4 of a four-volume edition of Walter Scott, Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (London: A.C. Black, 1807). Thanks to Nicholas Robinson for access to these volumes at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

[9] Letter from Christina Rossetti, February 6, 1865. Quoted in Rossetti Papers: 1862 to 1870, ed. William Michael Rossetti (London: Sands, 1903), 76.

[10] I draw here on E. Warwick Slinn, “Dramatic Monologue,” in A Companion to Victorian Poetry, ed. Richard Cronin, Alison Chapman, and Antony H. Harrison (Oxford: Blackwell, 2002), accessed July 29, 2021, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9780470693537.

[11] “True Love” is the only poem titled by Siddall herself.

[12] Carol Rumens, “Poem of the Week: Dead Love by Elizabeth Siddal,” Guardian, September 14, 2015, accessed August 3, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2015/sep/14/poem-of-the-week-dead-love-by-elizabeth-siddal. For Arcara a man warns a young woman about the fickleness of love and about the inconstancy of male flattery (41).

[13] Gabe Rivin, “What Happened to O?,” Paris Review, August 27, 2015, https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2015/08/27/what-happened-to-o/.

[14] Ibid. He quotes Goldstein on Sylvia Plath’s “Lady Lazarus.”

[15] Pray’s meaning to beseech another was then in use but is now archaic.

[16] “ferocia apocalittica con la quale la donna lancia le sue maledizioni all’amato.”

[17] Constance W. Hassett, “Elizabeth Siddal’s Poetry: A Problem and Some Suggestions,” Victorian Poetry 35, no. 4 (winter, 1997): 447–48, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40002261 [login required].

[18] Augusta Webster, “Poets and Personal Pronouns,” 1878, quoted in Richard Cronin, Reading Victorian Poetry (Oxford: Blackwell, 2012), 28.

[19] Zadie Smith, “The I who is not me,” Feel Free: Essays (London: Hamish Hamilton, 2018), 337, 346.

[20] For example, Isaac Watts’ hymn on the passage of the soul: “My soul, come meditate the day, And think how near it stands, When thou must quit this house of clay, And fly to unknown lands”. Thomas Haweis’s hymn “O thou from whom all goodness flows” has a similar repeated refrain to “Life and night . . .”

[21] Serena Trowbridge, “Gender and Space in Pre-Raphaelite Paintings of ‘The Eve of St Agnes,’” in Poetry in Pre-Raphaelite Paintings: Transcending Boundaries, ed. Sophia Andres and Brian Donnelly (New York: Peter Lang, 2018), 17–28.

[22] A few pages are stamped with the initials E.E.R. dating the composition or the copy to 1860–62; a few have black borders, used for mourning.

[23] Woolley considers Siddall wrote in secret and in private, not wishing or intending her work to be read by others.

[24] Trowbridge notes additional stanzas on pages 39 through 40 transcribed in the “Rossetti Album” in the Getty collection, accessed July 29, 2021, http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/gettymsbook.rad.html.

[25] W. M. Rossetti also remarked: “she developed a genuine faculty for verse as well as for painting—both assuredly under the stress of Rossetti’s prompting.” “Dante Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddal,” 291.

[26] Rumens, “Poem of the Week.”

[27] Smith, “The I who is not me,” 337.