New DiscoveriesFrançois Flameng, Grolier in the House of Aldus, 1889, Grolier Club, New York

by Eve M. Kahn

Eve M. Kahn

Independent Scholar

evemkahn[at]gmail.com

Citation: Eve M. Kahn, “François Flameng, Grolier in the House of Aldus, 1889, Grolier Club, New York,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 20, no. 3 (Autumn 2021), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2021.20.3.4.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

François Flameng’s painting Grolier in the House of Aldus (fig. 1) is not, strictly speaking, a new discovery. Since around 1890, it has been steadily on view at the Grolier Club in Manhattan. A preliminary sketch for the painting, also in the Grolier Club’s collection, appears on the Wikipedia article about Jean Grolier de Servières (ca. 1489–1565), the Renaissance bibliophile after whom the New York institution is named.[1] Yet the work is little known beyond the small circle of the club’s members and until recently has received little scholarly attention. In the last year, however, in-depth research about the painting has led to interesting discoveries related to its commission and its one-time popularity, expressed in reproductions made in diverse media for various purposes.

Painted in 1889 by Flameng (1856–1923), a French artist, Grolier in the House of Aldus depicts a meeting of the French collector Jean Grolier and the Italian printer Aldus Manutius (1449–1515) in Venice in the early 1510s. The painting was commissioned for the Grolier Club, founded in 1884 (North America’s oldest surviving bibliophile society), by one of its early members, the art dealer and philanthropist Samuel Putnam Avery (1822–1904). He ran a gallery at 366 Fifth Avenue at East Thirty-Fifth Street and lived with his wife, Mary Ann Ogden Avery (1825–1911), at 4 East Thirty-Eighth Street (building no longer extant). Near his home (fig. 2) and office, the Grolier Club opened its first headquarters, a Romanesque building designed by Charles W. Romeyn (1853–1942), extant at 29 East Thirty-Second Street. Grolier in the House of Aldus was commissioned for a large wall recess in the new building’s main exhibition hall.[2]

Among the Averys’ other gifts to the club were scores of fine bookbindings. One highlight is an exhibition checklist for a Grolier Club show of editions of the seventeenth-century author Izaak Walton’s The Compleat Angler from 1893. Its binding, by Tiffany & Co., is made of Javanese sharkskin and Florida garpike skin, with blue silk doublures patterned with gilded fish and a silk bookmark ribbon looped through a carved jade fish.[3] Avery also commissioned the Grolier Club’s medal with reliefs depicting Aldus in profile and his dolphin-and-anchor insignia; it was a facsimile of a medal that the printer commissioned in Venice around 1500, based on ancient Roman coins.[4] Other institutions also benefited from the Averys’ generosity. They gave varied objects and artworks, including a spoon collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Ching dynasty cloisonné vessels to the Brooklyn Museum, and prints by the thousands to the New York Public Library.[5] And they financed Columbia University’s architecture library, in memory of their son, architect Henry Ogden Avery, who died of tuberculosis in 1890—one of four of the couple’s six children to predecease them.

Avery likely knew François Flameng (fig. 3), age thirty-five at the time of the club commission, through the latter’s father, Léopold Flameng (1831–1911), a Paris-based etcher and engraver born in Belgium.[6] Working with a US agent in Paris, George A. Lucas, Avery avidly collected Léopold Flameng’s prints.[7] François Flameng had studied with his father, as well as with the Belgian painter and sculptor Constantin Meunier and the Parisian artist Jean-Paul Laurens. At the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris, François Flameng trained briefly with Alexandre Cabanel. While still in his teens, François Flameng began exhibiting artworks to acclaim at the Paris Salon. In 1881, he made a strategic marriage to Henriette Turquet (1863–1919), the daughter of the French arts patron and politician Edmond Turquet. Over François Flameng’s long career, he painted French Revolutionary and Napoleonic scenes, allegorical murals for institutional and commercial buildings, and portraits of society figures as well as of his wife and three children. He designed French banknotes and illustrated books, including Victor Hugo’s collected works. He also depicted World War I’s devastation, as documented in a book by the French scholar Alexandre Page published in 2019.[8] (François Flameng occasionally sat for portraits as well; in 1880, John Singer Sargent painted him alongside fellow artist Paul Helleu.)[9]

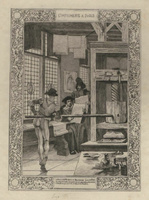

Avery’s hiring of his friend Léopold Flameng’s son for a tableau of Grolier and Aldus may have been partly due to François Flameng’s experience with related subject matter. Avery, a frequent traveler to Paris, was no doubt familiar with François Flameng’s mural in a Sorbonne stairwell depicting a fifteenth-century printing workshop (1887; fig. 4). Set in 1469, the scene shows Jean (Johann) Heynlin and Guillaume Fichet, two Sorbonne professors who were the founders of France’s first printing press, located in the university’s cellars. In the mural, the two men are proofing some newly printed pages under the watchful gaze of a figure in striped clothing, possibly representing one of the Swiss workmen they had brought in to operate the press.[10] Avery would have realized that François Flameng, a printmaker’s son who illustrated books, had expertise in conveying the importance of book patrons and artisans collaborating in major capitals at turning points in publishing history. Page notes that the Grolier Club commission also served as a crucial steppingstone for François’s career: “He wanted to extend his fame to America, where his father was already known.”[11]

On December 29, 1889, François wrote to Avery, explaining the nearly finished painting’s inspirations and source material.[12] What follows is an annotated translation by the author and a team of consultants led by scholar Henry Raine:[13]

Sir,

Permit me first of all to thank you. I am very much flattered to have been chosen to execute the panel for the Grolier Club, and although pecuniarily the affair was remarkably bad, I only regret that the work is not more important.

As you wished I have represented Aldus the elder in his printing house at Venice, receiving the visit of Grolier and showing him some bindings.

I first researched the location of the Aldus printing house, but regrettably I found no historical information that shed light on the matter. I imagined the establishment at the end of the quai des Esclavons; this scene is visible through the windows (the palace of the Doges, the Salute, S. Giorgio Maggiore, and the quai degli Schiavone). [Flameng wrote “quai des Esclavons” for the first reference to the Riva degli Schiavoni and “quai degli Schiavone” for the second.]

There is no likeness of Grolier in existence, the only known one having been on his tomb in the crypt of the church of St. Germain des Prés, Paris, and that stone carving no longer exists. [The church was badly damaged during the French Revolution, and no other verified likeness of Grolier has yet been found.] But happily there is one of Aldus, made about thirty years after his death, and we have those which ornamented the frontispieces of his books. I made use of all these portraits.

I have represented Grolier in the Milanese fashion of the beginning of the sixteenth century in costume half-French, half-Italian. As he was then very young and had always lived near his father in Italy, it is plausible that he wore the costume of the young Lombards with certain French customary pieces, such as the small hat, the shoes, doublet, and breeches. The coat is of Venetian cut; I copied it from a sixteenth-century coat that I purchased at the Baron Davillier sale. [Grolier is portrayed wearing a crimson-and-gold cape, modeled after a sixteenth-century Venetian cape that Flameng had acquired from the writer and art collector Baron Charles Davillier (1823–83).[14]]

As for Aldus, elderly at that time, his costume is of the fifteenth century, with the long black robe worn by old men of his day. I have only followed the portraits’ indications.

For the printing press I have used information from the library of San Marco, at Venice, and from a small press from the early sixteenth century, which survives in the Plantin printing house at Antwerp [now the Museum Plantin-Moretus].

The stained-glass panes that ornament the window represent the arms of Aldus [with dolphins and anchors].

I have placed on the printer’s stand the first page of your edition of the Philobiblon—it is an anachronism, but I thought later it will become a souvenir of one of the first publications of your interesting society (very worthy, because of its interest, of having been published by Aldus). [Flameng represented the title page of the Grolier Club’s 1889 edition of the English bibliophile Richard de Bury’s fourteenth-century essay collection.][15]

Here, sir, is all the necessary information. I have gilded certain parts of this painting executed in wax, to give it an amusing touch of archaism and a little more sparkle. The painting should remain absolutely matte and not be varnished.

Please, sir, accept assurances of my best regards.

Despite Flameng’s in-depth research, the painting has many features that would now be considered inaccuracies. Firstly, it depicts a scene that almost undoubtedly never happened. According to the scholars G. Scott Clemons and H. George Fletcher, “the evidence shows that Aldus Manutius and Jean Grolier met precisely once, in 1511, in the Treasurer’s house in Milan.”[16] Aldus operated chaotic, crowded workplaces in rather humble Venetian buildings (two addresses are known, on side streets near modern-day Campo Sant’Agostin and Campo Manin). His quarters almost definitely had no sweeping piazza and waterfront views, nor high ceilings, immaculately glossy floors, loose pages somehow unaffected by Venetian breezes, and marble Corinthian colonettes dividing arched windows. There would likely not have been any stained-glass panes, let alone colorful rondels depicting saints and surrounded by clear rectilinear panes—that Northern European Renaissance fenestration tradition can be seen, for instance, in Vermeer paintings.[17] (Flameng’s view of the cellar-printshop at the Sorbonne is similarly generously fenestrated, particularly improbable for a Parisian school basement.) The Museum Plantin-Moretus’s antique presses, which Flameng used as precedents for Aldus’s machine, were actually made a century after the printer’s death. Flameng’s preliminary sketch for the Grolier Club painting (fig. 5), which remained in Avery descendants’ hands, surfaced at a Bonhams auction in New York in 2010 (philanthropist Anne Hoy purchased it for the club).[18] Its waterfront-facing wall, an ethereal scrim of clear and tinted panes, is even more historically improbable than the version in the final painting. Grolier is portrayed husky, bearded, and approaching middle age—although he was barely twenty-five years old when Aldus died.

When the canvas was first displayed in New York, the art dealer Frederick Keppel deemed it “probably the most precious possession of the Grolier Club.”[19] The Collector’s editor, Alfred Trumble, praised the artist’s “close research and archaeological knowledge.”[20] Avery even paid Léopold Flameng to turn the painting into etchings (fig. 6). “I have very faithfully translated it,” the engraver told his patron.[21] The club published and marketed signed proofs on vellum and paper. (François Flameng’s Sorbonne mural was also adapted by his father into a widely published black-and-white print [fig. 7].)[22] The original copper plate remains in the club’s collection, along with multiple states of the etching and Léopold Flameng’s portraits of Shakespeare, Thomas Bewick, and the explorer Richard Burton.

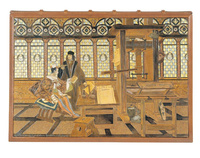

Avery also had the Flameng tableau adapted for a bookbinding (fig. 8) by the Parisian artisan Charles Meunier (1865–1940)—the son of François Flameng’s early teacher. Meunier rebound a history of bibliophiles, written and published by Jacques-Joseph Techener, a French antiquarian book dealer and bibliophile, from 1861.[23] According to Grolier Club staff members Eric Holzenberg and Fernando Peña, the binding gaudily combines Meunier’s repertoire of “inlay, onlay, paint, gilding, marbling, tooling, cuir ciselé—no technique is unrepresented.”[24] Meunier made minor changes to the original painting’s composition and palette. He closed the casement windows, rendered the panes in creamy lichen and metallic gold, lightened the chair cushion and Aldus’s robe, and added polychrome to Grolier’s tights.

In 1894, the engraver Edwin Davis French miniaturized the painting for the club’s bookplate (fig. 9).[25] Around this time, Frederick Wilson (1858–1932), a longtime staffer at Louis Comfort Tiffany’s glassworks, created a window (fig. 10) depicting Aldus in opulent Venetian quarters on commission for the main public library in Troy, New York. Glass historian Diane C. Wright has posited that the Grolier Club scene inspired Wilson’s opalescent view of a waterfront workplace, where a coed, bejeweled, multigenerational crowd ogles the printed word and papers spill floorward.[26]

Léopold Flameng’s etching of his son’s canvas traveled widely. Examples appeared at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1892, the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, and the Rowfant Club in Cleveland in 1897.[27] François Flameng’s sketch was shown at the Architectural League of New York in 1900.[28] Avery donated Léopold Flameng’s prints to institutions, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the British Museum.[29] His gift to the New York Public Library includes multiple states of the etching, similar to the Grolier Club’s set.[30] Grolier in the House of Aldus was reproduced on book frontispieces and in publications, including the Art Journal, Art Interchange, and Printing Art.[31]

Into the early twentieth century, the painting attracted public and media attention; the club owns a copper halftone block (fig. 11) used for its reproductions in various publications. In 1910, the literary critic Vance Thompson wrote a cover story on François Flameng for The Cosmopolitan, lauding the Grolier Club canvas “with its grave and delicate understanding of the men of the sixteenth century.” Thompson praised the Sorbonne printery scene as well, deeming it “an admirable decor, dignified, strong, rare in its sobriety.” He noted that although Flameng’s portrait subjects included European royals and American plutocrats, his historical scenes showed clear respect for workmen.[32] In 1917, the club put the canvas on view in a new neo-Georgian brick headquarters at 47 East Sixtieth Street (which remains the organization’s home), designed by club member Bertram Goodhue.

By the 1920s, however, skepticism surfaced about the painting, as its academic style went out of fashion and the estates of the Grolier Club’s founding generation were sold off—including their Flameng prints. In 1922, Edmund G. Gress, editor of the American Printer, roamed Venice seeking the marble-columned aerie where Grolier supposedly met Aldus. Gress realized that the workshop’s actual locations were unprepossessing, although Flameng “paid no attention to these traditional sites.”[33] The club’s seventy-fifth anniversary book from 1959 called the Meunier leather extravaganza “a treasured sentimental possession,”[34] implying perhaps that it was not to be taken seriously. In 1975, bookbinding scholar Anthony Hobson dismissed Flameng’s “fanciful” canvas as “once famous.”[35] In the 1990s, the fine press publisher Luke Pontifell used Léopold Flameng’s original plate for the Grolier Club’s restrike of one hundred numbered copies of the print. In the club’s show Aldus Manutius: A Legacy More Lasting than Bronze in 2015, an exhibition label described the Flameng painting as “artistic license run wild.”[36]

Today, the canvas still hangs prominently in the main gallery (albeit with some varnish that obscures the artist’s “amusing touch of archaism”). Meunier’s book is tucked into a glass-topped table in an upstairs corridor. François Flameng’s sketch adorns a stairwell, not far from the 1894 bookplate and some of Léopold Flameng’s etchings.[37] And so Avery’s gift of a portrait of his Renaissance role model in bibliophilism, swathed in crimson and gold, and starting to buy books from a venerable innovative printer about to retire, remains a linchpin of a Midtown Manhattan museum devoted to storytelling on the page.

Notes

[1] “Jean Grolier de Servières,” Wikipedia, accessed June 23, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

[2] “Two Benefactors of the Club,” Gazette of the Grolier Club, November 1921, 31.

[3] Grolier Club Library call number \19.5\C21.

[4] William Loring Andrews, Jean Grolier de Servier . . . (New York: The De Vinne Press, 1892), 24, 25, 66. Also see Robin Raybould, “Erasmus, Grolier, and Aldus,” in Gazette of the Grolier Club, ed. Declan Kiely (New York: Grolier Club, 2020), 55–68.

[5] Catalogue of the Collection of Spoons Made by Mrs. S. P. Avery . . . (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1899).

[6] Henry Pène du Bois, Four Private Libraries of New-York (New York: Duprat & Co., 1892), 42–72. I am grateful to the historian Madeleine Beaufort for her insights into Avery as a collector and patron.

[7] The New York Public Library owns hundreds of Léopold Flameng’s prints. S. P. Avery Collection, New York Public Library, New York.

[8] Alexandre Page, François Flameng (1856–1923), un artiste peintre dans la Grande Guerre (Puy-de-Dôme [Auvergne], France: self-published, 2019).

[9] In 2016, Colby College’s art museum acquired Sargent’s double-portrait of Flameng and Helleu, which had long remained in the Flameng family. Numerous journal entries by Flameng family friend Marguerite de Saint-Marceaux give glimpses of François’s social life and family. Journal de Marguerite de Saint-Marceaux: 1894–1927 (Divers Histoire, 14) (Paris: Fayard, 2007).

[10] Anatole Claudin, The First Paris Press (London: Bibliographical Society, 1898), 3.

[11] Alexandre Page, emails to the author, 2021.

[12] François Flameng, “Grolier in the Printing House of Aldus the Elder” (1889), box 1, folder 15, Grolier Club Artistic Properties Information File, 1889–[ongoing], The Grolier Club of New York, New York.

[13] Flameng, “Grolier in the Printing House of Aldus the Elder.”

Monsieur,

Permettez-moi d’abord de vous remercier je suis très flatté d’avoir été choisi pour exécuter le panneau destiné au Grolier Club, et quoi que pécuniairement cette affaire soit remarquablement mauvaise, je ne regrette qu’une chose, c’est que le travail ne soit pas plus important.

J’ai comme vous le désirez représenté Aldus l’ancien dans son imprimerie de Venise, recevant la visite de Grolier et lui montrant des reliures.

J’ai d’abord fait des recherches pour connaître l’emplacement de l’imprimerie Aldus, malheureusement je n’ai trouvé aucun renseignement de nature à m’éclairer. Et j’ai imaginé cet établissement au bout du quai des Esclavons; on voit tout ce paysage à travers les fenêtres (le palais des Doges, la Saluté, S. Giorgio Maggiore, et le quai degli Schiavone).

Il n’existe pas de portrait de Grolier—le seul connu ornait sa pierre tombale dans l’Eglise St Germain des Prés, Paris, et cette pierre n’existe plus, par contre il en existe un très heureusement de Aldus, fait environ 30 années après sa mort et nous avons ceux qui ornaient les frontispices de ses éditions. Je me suis servi de tous ces portraits.

Pour Grolier je l’ai représenté à la mode Milanaise du commencement du 16eme siècle son costume est moitié Français moitié Italien—comme à cette époque il était fort jeune et avait toujours vécu près de son père justement en Italie, il est vraisemblable qu’il portait—le costume des jeunes lombards avec certaines coutumes Françaises, comme la petite toque, les chaussures, le pourpoint, et le haut de chausses. Le manteau est de coupe Vénitienne, je l’ai copié d’après un ancien manteau du 16eme que j’ai acheté à la vente du Baron Davillier.

Quant à Aldus, très âgé à cette époque, il a un costume du 15eme siècle, la grande robe noire, comme la portaient les vieillards de ce temps. Je n’ai fait que suivre les indications des portraits.

Je me suis servi pour la presse des renseignements puisés à la bibliothèque de San Marco à Venise, et d’une petite presse du commencement du 16eme qui existe à l’Imprimerie Plantin d’Anvers.

Les vitraux qui ornent les fenêtres représentent les armoiries d’Aldus.

J’ai placé sur la tablette de l’imprimeur la première page de votre édition du Philobiblon—c’est un anachronisme, mais j’ai pensé que plus tard ça serait un souvenir d’une des premières publications de votre intéressante société (fort digne par son intérêt d’avoir été publiée par Aldus).

Voici monsieur tous les renseignements nécessaires. J’ai doré certaines parties de de cette peinture exécutée à la cire, pour lui donner un côté d’arcaïsme amusant ainsi qu’un peu plus d’éclat. La peinture doit rester absolument mâte et ne pas être vernie.

Agréez, monsieur, l’assurance de mes meilleurs sentiments.

[14] In the catalogue for an auction of Flameng family treasures in 1919—the artist sold many heirlooms after his wife died of diphtheria, contracted while she served as a battlefield nurse—the Davillier textile is listed as velours bouclé d’or (velvet textured with purled gold thread). Catalogue de Tableaux Anciens . . . (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, 1919), 109. I am indebted to historian Donna Ghelerter’s insights into Grolier’s finery.

[15] Richard de Bury, The Philobiblon (New York: Grolier Club, 1889).

[16] G. Scott Clemons and H. George Fletcher, “Aldus Manutius: A Legacy More Lasting than Bronze, an Exhibition at the Grolier Club, 25 February to 25 April 2015, Exhibition Wall Text,” in Kiely, Gazette of the Grolier Club, 121.

[17] I am grateful to the historians Julie L. Sloan and Alina E. Kulman for their insights into the windows.

[18] Bonhams New York, European Paintings sale, October 29, 2010, lot 76. Signed and inscribed “à mon bon ami Lucas François Flameng” (lower right), just below a partly illegible three-line inscription in a different hand at the printing press’s base: “Mille [illegible word, possibly eight letters, starting with c and ending in t] F. Flameng [illegible word, possibly four letters starting with h] / présente [?] ses [or perhaps nos?] mille saluts destinés / à ‘mon bon ami Avery’ G. [George] A. Lucas.”

[19] Frederick Keppel, “Mr. Keppel’s New Lecture,” The Collector, March 15, 1891, 120.

[20] Alfred Trumble, “A Gift to the Grolier Club,” The Collector, November 1, 1890, 5.

[21] Léopold Flameng letter and receipts to Samuel P. Avery, 1891, Samuel Putnam Avery Papers, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

[22] Albert Kelsey, The Architectural Annual (Philadelphia: Architectural League of America, 1901), 185.

[23] Jacques-Joseph Techener, Histoire de la bibliophilie . . . (Paris: Librairie de J. Techener, 1861).

[24] Eric Holzenberg and Fernando Peña, Lasting Impressions: The Grolier Club Library (New York: Grolier Club, 2004).

[25] Copies of French’s bookplate are widely scattered, for instance at the Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Theodore Sizer 1922.226.

[26] Diane C. Wright, “Frederick Wilson: 50 Years of Stained Glass Design,” Journal of Glass Studies 51 (2009): 201, https://www.cmog.org/.

[27] See Algernon Graves, The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors . . ., vol. 3 (London: Henry Graves and Co., George Bell and Sons, 1905), 123; Revised Catalogue, Department of Fine Arts . . . (Chicago: W. B. Conkey Co., 1893), 243; and A Show of Books . . . (Cleveland: Shelburne Press, 1897), n.p.

[28] Catalogue of the Fifteenth Annual Exhibition . . . (New York: Architectural League of New York, 1900), 27.

[29] Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, accession no. M7394, donated March 21, 1891; and British Museum registration no. 1891,0627.136.

[30] See note 7.

[31] Examples of frontispieces include Howard J. Rogers, ed., International Congress of Arts and Science, vol. 15 (New York: University Alliance, 1908); and Charles Meunier, Cent reliures de la Bibliothèque Nationale (Paris: Société des Amis du Livre Moderne, 1914). Publications include Georges Cain, “Francois Flameng,” in Art Journal (London: J. S. Virtue & Co.), 1891, 65–71; Henry Gower Hose, “The Grolier Club ‘Transactions,’” Art Interchange (New York), May 1895, 126; and Printing Art (Cambridge, MA), August 1903, frontispiece.

[32] Vance Thompson, “Flameng—Interpreter of Beauty,” The Cosmopolitan, March 1910, 403–8. The Hermitage owns Flameng’s portraits of Empress Maria Feodorovna (inventory number ЭРЖ.II-685) and Princess Zinaida N. Yusupov (ЭРЖ-1370). Buckingham Palace displays Flameng’s portrait of Queen Alexandra (RCIN 405360), Empress Maria Feodorovna’s sister. Among his US clients were Adaline Noble (her portrait at the Smithsonian American Art Museum is object no. 1933.4.3) and Ruth Livingston Mills (his portrait of her hangs at her former home, Staatsburgh State Historic Site in Staatsburg, NY).

[33] Edmund G. Gress, “An American Printer’s Dash through Europe,” American Printer, September 5, 1922, 28–30.

[34] Grolier 75 (New York: Grolier Club, 1959), 1.

[35] Anthony Hobson, Apollo and Pegasus: An Enquiry into the Formation and Dispersal of a Renaissance Library (Amsterdam: Van Heusden, 1975), 103.

[36] See note 16.

[37] After a version of this article appeared as a blog post on the Grolier Club’s website, Alexandre Page noted that some of its information and images were new to him, including the existence of the Meunier binding. Page states that the father and son artist team, so long “unjustly forgotten,” now merit “a major exhibition” that would give them “visibility and rehabilitation.” Page, emails to the author, 2021.