American Art History Digitallysponsored by the Terra Foundation for American ArtImpossible Garden: A Contemporary Artist’s Digital Engagement with Women Artist-Naturalists of the Long Nineteenth Century and BeyondInterview with Emma Steinkraus

by Emma Steinkraus, with Carey Gibbons and Allan McLeod

Emma Steinkraus is a visual artist and assistant professor of fine art at Hampden-Sydney College. Her paintings and installations use strategies of juxtaposition and layering to explore ecology, gender, and the history of science. Her current project, Impossible Garden, highlights the contributions of women artist-naturalists through an immersive wallpaper collaged from reproductions of their work. Steinkraus’s work has been exhibited recently at galleries including 1969 Gallery (New York, NY), Deanna Evans Project (Brooklyn, NY), Poker Flats (Williamstown, MA), and Field Projects (New York, NY). She has been awarded artist residencies at the Studios at MASS MoCA, the Wassaic Project, the Blue Mountain Center, and the Vermont Studio Center, where she is a Helen Frankenthaler Fellow. In 2020, she was an Eliza Moore Fellow for Artistic Excellence at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation. Her work can be found on her website or on Instagram at @emmasteinkraus.

Email the author: woodemma[at]gmail.com

Carey Gibbons, Digital Art History Editor, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide

Citation: Carey Gibbons, “Interview with Emma Steinkraus,” in Emma Steinkraus, with Carey Gibbons and Allan McLeod, “Impossible Garden: A Contemporary Artist’s Digital Engagement with Women Artist-Naturalists of the Long Nineteenth Century and Beyond,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 20, no. 3 (Autumn 2021), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2021.20.3.29.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Editor’s Introduction|Interactive Feature|Interview|Project Narrative

Interview with Emma Steinkraus by Carey Gibbons

Carey Gibbons (CG): Can you explain the decision behind the title Impossible Garden?

Emma Steinkraus (ES): Impossible Garden is a research-based art project that depicts a panoramic landscape constructed from highly disparate sources. I made it using Adobe Photoshop to collage together imagery of flora, fauna, and fungi produced by women artists between roughly the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. My organizing principle was incredibly broad: if an image depicted a plant, mushroom, or animal in color and was made by a woman more than a hundred years ago, then it could belong. The result isn’t a realistic—or even possible—habitat. Instead, I think of it as a compendium of close looking that crosses borders of time and space, a garden in which a single tree might contain foliage, birds, and insects derived from illustrations made by women who worked across three centuries and as many continents.

So perhaps that explains the “impossible” in the title, but I also wanted the project to feel like a garden: immersive, abundant, and both ordered and unpredictable. At their best, gardens are experiments in caring for other organisms as they care for us. That ethos is one I hope to explore across my work, and one that I discovered time and again in the work of the historical women presented here.

CG: How does this project for NCAW develop or build on your previous work for Impossible Garden?

ES: Originally, this project took the form of a printed wallpaper that was a part of my solo exhibition in the Project Space at 1969 Gallery in New York City from July 8 to August 20, 2021 (fig. 1). Printed at that scale, the animals and plants were life-size and surrounded the viewer. The wallpaper was layered with paintings based loosely on the stories of historical women artist-naturalists. It was an exciting way to interact with Impossible Garden, but not one that was conducive to extensive annotations or historical context.

Fig. 1, Installation view of Emma Steinkraus, Impossible Garden, Project Space at 1969 Gallery, New York, 2021. Printed wallpaper and paintings with oil and photo transfers on canvas. Image courtesy of 1969 Gallery.

I knew I wanted to create a complementary way for viewers to learn more about the research and history that animated Impossible Garden. When NCAW reached out to me, this seemed like the perfect collaboration for creating a navigable, annotated version of the project that could be accessed online. I was also excited to incorporate new writing and original visual components, including the pink and red rose bushes.

CG: This project encourages us to reflect on the contemporary relevance of nineteenth-century art. Can you explain why you, a contemporary artist, are drawn to nineteenth-century art, and nineteenth-century botanical and natural history illustrations in particular? When did you first start working with these illustrations?

ES: This project has deep roots for me. My interest in natural history started in childhood. I grew up in the Arkansas Ozarks around naturalists. My dad is an entomologist and my mom is an excellent amateur botanist. Creatures were part of the rhythm of daily life around our house; you might find a tomato hornworm in the freezer or an observation beehive on the mantle. When my sister and I talk on the phone, our conversations are about what snakes or moths we’ve seen lately. Paying attention to other organisms is a deeply ingrained habit; one I wanted to find reflected in art.

I also struggled for a long time to find female role models within the art historical canon as I encountered it in books, schools, and museums. I was hurt by the historical marginalization of women artists and angry at the gender inequities that persist in the art world.[1] I was also struck by the unfairness of Western genre hierarchies: between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, European art theorists placed figurative art above landscapes, animal paintings, and still lifes.[2] In a very literal way, paintings of humans have been valued above those of other species. For me, living in a society that devalues art made by women and art about non-human nature feels intimately connected to the sexism and ongoing environmental crises that impact my life, which is to say, I take it personally.

I began this project about three years ago, hoping to find a lineage of women artists who shared my interest in natural history. I started looking at the nineteenth century and earlier because I couldn’t name many women artists who worked then. It turned out to be a serendipitous choice. Botanical art and scientific illustration were unusually accessible genres for women at that time. Sexist norms and barriers to education meant few women had the resources to paint, say, nudes on huge canvases, but studies of nature could be small, portable, and on paper. In Europe and the United States, there was also less societal resistance to women making botanical art. As John Claudius Loudon explained: “to be able to draw Flowers botanically. . . is one of the most useful accomplishments of young ladies of leisure.”[3]

As the project developed, my interest in the nineteenth century broadened. The lives of the women in this project led me to research many other things, from the colonization of Tasmania to abolitionist organizing in Philadelphia in the 1830s. Over time, I came to see that the nineteenth century was not so long ago really; we still live in its wake. Our world is shaped by the unresolved traumas of the nineteenth century, especially slavery and colonialism. The forms of justice that many fought for in the nineteenth century—for abolition, women’s rights, labor rights, and environmental protections—have not been fully realized. Nineteenth-century history is very unfinished business, and learning about the specific ways that oppression and activism played out in the everyday lives of people from the past made the present more legible.

CG: Do you see women’s persistent engagement with the natural world through the medium of illustration as part of a larger effort by women to claim a space for themselves? Can you explain how this is reflected in both your collaged wallpaper design and your paintings featuring women artist-naturalists? For example, in the works incorporated into your wallpaper that feature plants and animals with anthropomorphic qualities, were women artist-naturalists expressing a correspondence between the lives of plants and animals and their own lives and/or did illustrations provide them with a unique opportunity to express their own personal desires and anxieties?

ES: These are questions that really interest me. The women in this project asserted themselves in a variety of ways—some of which are legible in their biographies, others in their work—as they sought to fulfill their artistic and scientific ambitions.

Many, for example, fought against being confined to the roles of wife or mother. A surprising number didn’t marry or only married later in life, in their forties or fifties.[4] Those who did marry often found creative workarounds. The sixteenth-century Korean artist Shin Saimdang, for example, demanded that her husband study alone on a mountain for ten years, while the seventeenth-century German-born entomologist Maria Sibylla Merian left her husband and absconded with her mother and two daughters to an anti-hierarchical commune in a castle.

They chafed against societal expectations for women. Louisa Atkinson shocked her contemporaries by turning her skirts into trousers. Mary Delany was a bluestocking. Anna Maria Hussey wrote, “I am always under the uncomfortable impression that the thing I am doing is not the right thing to be doing.”[5] Her fellow mycologist Mary Banning put society’s assessment even more bluntly: “They regard me as a crazy woman.”[6]

They fought—often unsuccessfully—for institutional support: for access to formal education, professional circles, and paid opportunities. Banning worked for twenty years on the first illustrated, popularly accessible guide to American fungi; she sent her only copy to Charles Peck in hopes of having it published. It languished in a drawer for nearly a hundred years and still hasn’t been published today. The ornithologist and activist Graceanna Lewis repeatedly applied for professorships but was never hired; “I do not hope at all,” she wrote in a letter after applying to a job at Vassar, “not because I have not the very best of recommendations, but because of the preference for a masculine representative.”[7] Beatrix Potter received a posthumous apology from the Linnean Society for their sexist dismissal of her mycological research.[8] It seems inevitable to me that these lived experiences influenced their artistic work, and vice versa, but most of these women were not making images that look like “feminist art.” And, yet, I do think their work invites feminist close readings.

Many of the artists I’m studying seemed to identify with other organisms. Often, they describe other species using tropes or descriptions normally reserved for women. For example, one of Atkinson’s favorite devices was to give an animal a little flower or leaf to hold, evoking an extensive history of portraits of women holding plants in just this way (figs. 2–6). Hussey did something similar for mushrooms by describing them using the language of fashion. Her “gorgeous” (and sometimes “dowdy”) mushroom friends wear “quiet Quaker garb,” or “a velvet coat,” or “a surtout of the smoothest kid-leather.”[9] Seen through a microscope, mildew is “tasseled with pearls.”[10] Her drawings are like mycological fashion plates. An upside-down golden chanterelle swishes around in a flouncy yellow skirt, while an earth star runs off to a ball (figs. 7–8).

Jane Bennett writes in Vibrant Matter (2010) that we “need to cultivate a bit of anthropomorphism—the idea that human agency has some echoes in non-human nature—to counter the narcissism of humans in charge of the world.”[11] This kind of anthropomorphism, one that asserts non-human agency, is what I have found in the work of many women. My hunch is that working at the margins, as outsiders and amateurs, made it easier for women artist-naturalists to greet fellow creatures—often themselves exploited or marginalized—with empathy and warmth.

I also suspect that many of these women found in non-human nature evidence that gender could be constructed differently. In Merian’s study of a Suriname toad or Dorothea Graff’s famous drawing of a mother caiman, we encounter female animals divorced from any societal pressure to be “pretty,” “demure,” or “nice” (figs. 9–10). It doesn’t surprise me that a great many of these women had a special interest in insects, whose matriarchal societies disturbed many of their contemporary male peers.

In an article for Art Herstory called “The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian” from 2019, I elaborated on this idea. In Europe during the seventeenth century, nature was widely considered a “second Bible” that revealed the hand of God.[12] Its exegesis, however, proved subversive. Observations about insects revealed paradigm-shifting truths. In 1609, Charles Butler published The Feminine Monarchie, in which he argued that the head of the beehive was not a king, as had been thought, but a queen. This discovery provoked what Drar Wahrman has called “a crisis” in the understanding of gender across Europe.[13] I wonder if these insect matriarchies might have emboldened the women who studied them to reject conventional gender expectations (figs. 11–13).

My own work reflects my engagement with both the biographies and the oeuvres of women artist-naturalists. The wallpaper foregrounds their artistic achievements, forming a sweeping survey of encounters between women and other species, while the paintings grapple with the complexities of some of their individual lives (fig. 14).

Fig. 14, Emma Steinkraus, Picking Oranges (for Dido Elizabeth Belle, Giovanna Garzoni, & Zaga Christ), 2021. Oil and photo transfers on canvas. Private collection. Image courtesy of Emma Steinkraus.

Stylistically, my work embraces many aesthetic elements with feminine associations. My paintings are full of bows, ruffles, and pastel colors. Textiles, fashion, and interior design all exert clear influences. My current paintings are not so different from the elaborate paper dolls I made as a kid: I still enjoy costuming women in fantastical outfits. Yet I am also interested in refashioning genres associated with versions of art history that excluded women. Many of my paintings blend portraiture and narrative painting, and frequently reference the poses found in European history paintings of religious or mythological scenes. Hanging these figurative works alongside paintings and pastels of plants, animals, and fungi is an attempt to flatten traditional Western genre hierarchies and assert the historical importance of both women and non-human nature (fig. 15).

Fig. 15, Installation view of Emma Steinkraus, Impossible Garden, Project Space at 1969 Gallery, New York, 2021. Printed wallpaper and paintings with oil and photo transfers on canvas. Image courtesy of 1969 Gallery.

CG: You’ve mentioned that it was much easier to find examples of work by white, wealthy women artist-naturalists than by women of color and/or modest socioeconomic backgrounds when completing your research for Impossible Garden. How does your work (either your paintings or wallpaper) examine racism, colonialism, and class?

ES: For me, one gap in the record led to another. I started looking for women artists because I couldn’t find enough. But as I found more women artists, I noticed that they were overwhelmingly white and privileged.[14] I knew that there had been women from all times, places, and socioeconomic backgrounds who observed non-human nature with an artist’s eye, so my questions were: What forms did their observations take? Was any trace of them preserved? And, if not, why? I saw each lacuna as an invitation to search harder and research more carefully the systems of value that had created the archive as I found it.

One aspect of my project has been to try to look at the injustices of the archive—its whiteness and elitism—head-on. While this project began as a celebration of work by women, it grew more critical as I learned how often the women I was studying failed to extend their versions of feminism to those who were enslaved, poor, or the Indigenous inhabitants of colonized land.

The painting Pink Caiman (after Maria Sibylla Merian), for example, wrestles with the legacy of Maria Sibylla Merian’s research in Suriname, which was then under brutal Dutch colonial rule. Merian’s magnum opus documenting the insects of Suriname has been called one of the first works of ecology, but it was built on the exploitation of the uncredited, enslaved Surinamese women who worked as her guides.[15] In the painting, the white gaze has distorted the creatures being observed into pink, fleshy reflections of whiteness (figs. 16–17). The dress is patterned with photo transfers that connect Dutch “Golden Age” painting to colonial extraction and juxtapose imagery of the past with images of neocolonialism today as it manifests in trade, consumption, and the vacation industry.

Fig. 16, Emma Steinkraus, Pink Caiman (after Maria Sibylla Merian), 2021. Oil and photo transfers on canvas. Private collection. Image courtesy of Emma Steinkraus.

Fig. 17, Detail of Emma Steinkraus, Pink Caiman (after Maria Sibylla Merian), 2021. Oil and photo transfers on canvas. Private collection. Image courtesy of Emma Steinkraus.

Another aspect of this project has been to search for and highlight work by women who weren’t white or wealthy, women like Sarah Mapps Douglass, Shin Saimdang, Yun Bing, and Mary Banning, all of whom deserve so much more attention and scholarship.

The painting Daisy Chain (for Sarah Mapps Douglass, Amy Matilda Cassey, and Matilda Evans) is loosely inspired by Douglass, an activist, poet, and artist, as well as her circle (fig. 18). Douglass is one of the most extraordinary women I’ve encountered through my research. She was a founding member of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Association. At twenty-five she helped start the first social library for Black women in the US and began fundraising for The Liberator, an abolitionist newspaper. In the years that followed, she founded a school for Black girls, a home that provided care for “aged and infirmed colored people,” and a lecture series that helped poor women gain control over their reproductive lives. After the Civil War, she started the Women’s Freedmen’s Relief Association, which sent clothes, books, teachers, and tools to Southern Black communities. All this while also painting, teaching, writing poetry, and studying medicine.

Fig. 18, Emma Steinkraus, Daisy Chain (for Sarah Mapps Douglass, Amy Matilda Casey, and Matilda Arabella Evans), 2021. Oil on canvas with acrylic medium transfers of drawings by Sarah Mapps Douglass and archival photographs. Private collection. Image courtesy of Emma Steinkraus.

Douglass’s extant paintings were made when she was a young woman for a friendship album curated by Amy Matilda Cassey. In the painting based loosely on her and her circle, I wanted to emphasize the role of friendship and Douglass’s interest in nature. Her illustration of a butterfly is included in the wallpaper, perched close by, and echoed in the pipevine swallowtail that flies through the upper-left corner. The floral pattern on the dress on the right is created from photo transfers of her illustrations, while the dress on the left is patterned with photographs of other women who formed Douglass’s milieu as activists, artists, and medical providers.

CG: How would you situate the United States’ natural history within a transnational context? Are there differences and/or crossovers between the ways in which US women artist-naturalists and their counterparts in Europe and/or Asia saw the natural world?

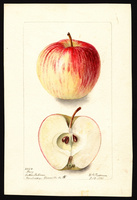

ES: In many ways, this is a project about entanglement: with other organisms, with other people and places, and with the past. Art and natural history in the United States can’t be easily isolated from global history. Deborah Griscom Passmore worked for the United States Department of Agriculture painting apples, which seems like a very “all-American” project at first, but apples were first cultivated in the Tian Shan mountains near modern Kazakhstan, and Passmore paints them in a style developed by generations of European botanical artists (fig. 19).

Many of the women in Impossible Garden were explicitly inspired by women artists of the past, including those from very different places. Sarah Mapps Douglass sometimes wrote under the pseudonym Sofonisba after the Italian Renaissance painter Sofonisba Anguissola.[16] In studying Chinese art, I learned that Tang Souyu wrote a history of women artists in 1824 that includes 216 women painters from across the ages—way more women than are in my own modest project.[17] I’m far from the first woman artist who has wanted to know about women artists of the past, including those who lived in very different times and places.

That said, I’m still learning how to situate my understanding of natural history within a transnational context. Impossible Garden is a product of curiosity, not expertise. I’m not a trained historian or art historian. It’s an amateur project, and I’m proud of that. Many of the women I’m studying were also amateurs. It’s a beautiful word, “amateur”: to study something for love.

There are many aspects of global art history I want to know more about. I’m especially new to studying East Asian art. Slowly I’m learning more about the many Ming- and Qing-dynasty women who painted flora and fauna. Some aspects of their lives are familiar, as they too labored within patriarchal societies that limited the scope of their education, travel, and professional opportunities. On the other hand, botanical art played a very different role in Chinese art history than in Western art history. Bird-and-flower painting was a major genre for artists of all genders, unlike in the West, where botanical art was often neglected and feminized.

CG: How does the contemporary concern over climate change, environmental degradation, and the decline of biodiversity relate to your project? Did any of the nineteenth-century women artist-naturalists selected for your project express particular concern about the human impact on the environment or the fate of plant and animal life? Additionally, how does your work fit within the context of writings by scholars of ecofeminism, such as Donna Haraway?

ES: What’s happening to the biosphere is terrifying, catastrophic. We’re living through the sixth great extinction of life on this earth. It’s a scale of biological annihilation that is completely unprecedented within the span of human existence. The current extinction rate is one hundred times higher than normal, which means that every year we lose a century’s worth of species.

In my lifetime, the monarch butterflies I used to watch migrate each fall have declined by 90 percent, a loss of nine hundred million individual butterflies.[18] Populations of migratory freshwater fish have declined by 76 percent since 1970.[19] The number of fish in the ocean has been halved.[20] We’re cutting down fifteen billion trees a year.[21] In the US we’ve destroyed nearly one hundred million acres of topsoil.[22] We’re depleting groundwater at an alarming rate. I haven’t even mentioned climate change yet. I don’t think anyone has the emotional and intellectual tools to adequately process what we are losing or the danger we’re in.

I often feel environmental degradation as background stress, repressed panic. It permeates all my work, but obliquely. While I think a lot about the politics of my work, I also see art as a slow, winding, unwieldy form of political action. There are powerful things that we can do to support ecosystems and build a more just world, and most of them are not art. Some of my favorite women in this project were artists and activists, like the abolitionists Sarah Mapps Douglass and Graceanna Lewis, or the conservationists Louisa Atkinson and Beatrix Potter.[23] They remind me that making art is both important and insufficient.

That said, I do feel like the women I’m studying have taught me a variety of artistic strategies for articulating an ecological ethic. For example, many of the women in this project focused on creatures that were overlooked or demeaned, like insects or mushrooms. Almost none painted megafauna, like the lions and stags found in work by many of their male contemporaries.[24] Creatures shouldn’t have to be “majestic” or “charismatic” or “exotic” for us to care about their existence and well-being.

On average, the artists in this project also have a noted preference for observing living animals at a time when many scientific illustrators worked from dead specimens. Time and again I’ve come across snippets like Maria Sibylla Merian asking James Petiver to please stop sending her dead specimens because she was only interested in living insects and “the formation, propagation, and metamorphosis of creatures, how one emerges from the other [and] the nature of their diet.”[25] Or a letter about Elizabeth Gwillim drawing living birds that “stare, or kick, or peck, or do some vile trick or other that frightens her out of her wits.”[26] Most approached non-humans as fellow living beings, rather than as trophies or specimens.

In many ways, the women in this project depict what Donna Haraway calls an “intersecting gaze” of reciprocity across species.[27] Their work testifies to the agency of other organisms and sees in them something akin to, but broader than, humanity. Let’s call it “creaturity”: the dignity and innate worth of living things.

The Impossible Garden series uses a variety of strategies to articulate an ecological ethic. Within my paintings, I almost always situate humans within a world that includes other organisms, and I try to make plants and animals as detailed, lively, and specific as their human counterparts. Like many of the women in my project, I’m especially interested in creatures that are small, ordinary, or maligned. My work is full of bugs, toads, and mushrooms. Perhaps you can see the influence of the women I’m studying in a piece like Cabbage with Eight-Spotted Forester Moth (fig. 20). While I was making it, I thought about Anna Maria Hussey’s special ability to make mushrooms look like they are twirling around in ball gowns. I wanted to give the cabbage a similar joie de vivre, to show it delighting in the sun, rain, and good soil, as I know cabbages do.

Fig. 20, Emma Steinkraus, Cabbage with Eight-Spotted Forester Moth, 2021. Pastel on paper. Private collection. Image courtesy of Emma Steinkraus.

CG: There is an interesting interplay in your work between the idea of discrete elements or fragments collaged together and the idea of a unified, immersive experience. Can you discuss the relationship between these two concepts in your work and explain how you use individual pieces or components to create a cohesive, immersive panoramic garden landscape? Additionally, can you comment on the difference between the multidimensional experience of nature in your garden and the more focused engagement with nature associated with the creation and study of botanical illustrations?

ES: I created an immersive, cohesive space for a number of reasons, some intuitive and some deliberate. A central argument of Impossible Garden is that women artists before the twentieth century were less scarce than we’ve realized but have been overlooked because they often worked in the neglected genres of botanical and scientific art. To realize that argument visually, I needed to present overwhelming evidence of women’s artistic production in those genres. My goal was to communicate the abundance and diversity of images made by women and the centrality of non-human nature to their artistic practices.

I also wanted to reframe their work. I think one of the reasons that depictions of flora and fauna have been historically overlooked is that each individual work is often a small part of a larger project. The ambition of many artist-naturalists is realized through a series or book project. I thought that constructing a more panoramic, simultaneous view of their work might make it easier for viewers to immediately comprehend the scope of their contributions. Creating a shared visual context for their work also emphasizes the connections between women across cultural and generational divides. In the words of Vera Norwood, I wanted to “shift singular women away from their subordination within the male-dominated stream of environmental history and situate women’s group achievements within female culture.”[28]

As an artist, I use a lot of collage, which always involves building something cohesive out of smaller, disparate parts. Nearly all of my paintings include acrylic-medium photo transfers, which are a form of collage where the ink from a toner-based print is transferred to another surface. For this series, the transfers make up the patterns on the clothing, embedding archival and contemporary images directly into the painting’s surface. They work almost like visual footnotes. The transfers annotate the paintings, acknowledging the source material and providing viewers a way into the associative “internet rabbit hole”–style research that goes into every piece. Whether I’m making paintings, digital projects, or wallpaper installations, I find collage a useful tool for toggling between the collective and the individual, the human and the non-human, the historical and the present.

CG: There is also an interesting interplay or tension in your work between artifice and the natural world. Can you explain why this tension exists and how it relates to your concern with the ambitions and experiences of women artist-naturalists during the nineteenth century?

ES: I didn’t intentionally cultivate a tension between the artificial and the natural. Some of the aesthetic decisions that look artificial were either practical or intuitive. The project has a flat, digital aesthetic because I made it in Adobe Photoshop in order to move around hundreds of discrete images. I gave the sky a gradient because I’m a ’90s kid raised on Lisa Frank. Objects rarely overlap because I wanted each art historical image to be legible.

There are almost certainly more interesting ways to interpret the relationship between artifice and nature in my work, but I have trouble seeing my own style clearly. When I’m making aesthetic decisions, I feel like a MacGregor’s bowerbird building his bower or a beaver building a dam. Arranging things until they look “right” is one of the things that the particular animal that I am likes to do. What might look artificial feels natural to me.

That said, I haven’t shied away from qualities associated with artifice, like flatness and digital construction. I’m interested in theatricality and trompe l’oeil. Representational painting has always felt like a magic trick to me: you take a flat canvas and voilà! it becomes a person or a place. I often use iconography that draws attention to flatness and illusion. The painting Frog Ballet (for Beatrix Potter), for example, is set in a Victorian paper theater, while Cut Paper (for Mary Delany, Sylvia Drake, & Charity Bryant), includes two paper dolls (figs. 21–22).

Fig. 21, Emma Steinkraus, Frog Ballet (for Beatrix Potter), 2021. Oil on linen. Private collection. Image courtesy of Emma Steinkraus.

Fig. 22, Emma Steinkraus, Cut Paper (for Mary Delany, Sylvia Drake, & Charity Bryant), 2021. Oil and photo transfers on canvas. Private collection. Image courtesy of Emma Steinkraus.

CG: Your creation of a garden encourages us to reflect on the different ways we comprehend or experience nature. How is the experience of knowledge different in the garden versus in the wilderness? How does the sense of interactivity and free play within the digital space of your project replicate or diverge from our experience of gardens in the real world?

ES: Wilderness is an interestingly contested word, and I’m not sure where I stand. Emma Marris wrote a book called Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World (2013) that I read years ago.[29] If I remember it correctly, she argues that human-caused climate change, among many other factors, means there aren’t any true wildernesses because no place on Earth is unaffected by human activity. If every environment is shaped by humans, then one way to look at the Earth is as a giant garden—one that is under our control and that we need to learn to tend to better.

I’m sympathetic to that argument, and to related critiques of “wilderness” and “nature” by thinkers like William Cronon or Timothy Morton.[30] Though I also wonder if defining wilderness as a place untouched by humans sets up a straw man. Paul Kingsnorth talks about the wild as a place that is “lived in and off of by humans, but . . . is not created or controlled by them,” a space where no one species dominates.[31] That feels like a more useful definition of wilderness and one we can actually work toward realizing.

Maybe all this is to say that I see “gardens” and “wildernesses” as different points within a matrix of human/non-human entanglement. Both are collaborative interspecies environments that humans have impacted for millennia, though to different extents.

Impossible Garden is inspired by some of the things I like best about gardens—the joy of looking at other species, the controlled unruliness, the surprise encounters with insects and other small organisms. My hope is that this digital project mimics many of those qualities, encouraging viewers to explore an archive in a playful, nonlinear way. But perhaps one last reason it’s an “impossible garden” is that no digital project or wallpaper can really compare to a garden, with its wealth of other lives, other intelligences. The wisdom, problem solving, joy, and meaning contained within the biosphere will always outstrip anything humans can construct on their own. So, you know, get off whatever device you’re reading this on and go outside.

Notes

[1] To learn more about contemporary gender inequity in the arts, view the statistics compiled by the National Museum of Women in the Arts: “Get the Facts,” National Museum of Women in the Arts, accessed September 25, 2021, https://nmwa.org/.

[2] Emmelyn Butterfield-Rosen, “The Hierarchy of Genres and the Hierarchy of Life-Forms,” Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 73/74 (2020): 76.

[3] John Claudius Loudon, The Gardener’s Magazine and Register of Rural and Domestic Improvement, vol. 7 (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1831), 95.

[4] Mary Kirby married at age forty-three, Beatrix Potter at forty-seven, Sarah Mapps Douglass and Sarah Anne Drake at age forty-nine, and Anne Pratt at sixty. Teresa Vitelli, Lydia Shackleton, Mary Banning, and Graceanna Lewis never married, while Giovanna Garzoni had her marriage annulled.

[5] Anna Maria Hussey to Miles Berkeley, quoted in Judith W. Page and Elise L. Smith, Women, Literature, and the Domesticated Landscape: England’s Disciples of Flora, 1780–1870 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 111.

[6] Alicia Puglionesi, “The Lost Mushroom Masterpiece Unearthed in a Dusty Drawer: How an Obscure Woman Mycologist Left Her Mark on Fungi,” Atlas Obscura, July 27, 2016, https://www.atlasobscura.com/.

[7] Marcia Bonta, “Graceanna Lewis: Portrait of a Quaker Naturalist,” Quaker History 74, no. 1 (Spring 1985): 36.

[8] 8 Rebecca Stiffe, “The Surprising Life of Children’s Writer and Natural Scientist Beatrix Potter,” Irish Examiner, July 29, 2019, https://www.irishexaminer.com/.

[9] See Anna Maria Hussey, Illustrations of British Mycology, Containing Figures and Descriptions of the Funguses of Interest and Novelty Indigenous to Britain, vol. 1 (London: Reeve, Benham, and Reeve, 1847), n.p., plate 76; Hussey, Illustrations, vol. 1, n.p., plate 47; Anna Maria Hussey, Illustrations of British Mycology, Containing Figures and Descriptions of the Funguses of Interest and Novelty Indigenous to Britain, vol. 2 (London: Reeve, Benham, and Reeve, 1855), n.p., plate 9. Hussey, Illustrations, vol. 2, n.p., plate 17; Hussey, Illustrations, vol. 2, n.p., plate 23.

[10] Hussey, Illustrations, vol. 2, n.p., plate 17.

[11] Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), xvi.

[12] Emma Steinkraus, “The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian,” Art Herstory, August 9, 2019, https://artherstory.net/protofeminist-insects-in-art/.

[13] Drar Wahrman, quoted in Deirdre Coleman, “Entertaining Entomology: Insects and Insect Performers in the Eighteenth Century,” Eighteenth-Century Life 30, no. 3 (Summer 2006): 115.

[14] I also want to call attention to the limitations of this project. I looked for observational drawings, prints, and paintings, which are not major art forms in every tradition. The geographic, racial, and socioeconomic diversity of this project might be very different if I had included more abstract depictions of nature, work by unnamed artists, or work in other media.

[15] This idea comes from Kay Etheridge’s essay, “Maria Sibylla Merian: The First Ecologist?,” in Women and Science, 17th Century to Present: Pioneers, Activists and Protagonists, ed. Veronique Molinari and Donna Spalding Andreolle (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011), 35–54.

[16] Mary Kelly, “‘Talents Committed to Your Care’: Reading and Writing Radical Abolitionism in Antebellum America,” New England Quarterly 88, no. 1 (2015): 42.

[17] Tseng Yuho, “Women Painters of the Ming Dynasty,” Artibus Asiae 53, no. 1–2 (1993): 251.

[18] Brooke Jarvis, “The Insect Apolcalypse Is Here,” New York Times, November 27, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/.

[19] Stefan Lovgren, “Many Freshwater Fish Species Have Declined by 76 Percent in Less than 50 Years,” National Geographic, July 27, 2020, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/.

[20] Alister Doyle, “Ocean Fish Numbers Cut in Half since 1970,” Scientific American, September 16, 2015, https://www.scientificamerican.com/.

[21] Justin Worland, “Here’s How Many Trees Humans Cut Down Each Year,” Time Magazine, September 2, 2015, https://time.com/.

[22] “One-Third of Farmland in the U.S. Corn Belt Has Lost Its Topsoil,” Yale Environment 360, February 18, 2021, https://e360.yale.edu/.

[23] Potter’s legacy as a conservationist is complicated. She bequeathed four thousand acres of countryside and fourteen farms in the Lake District to the National Trust, helping form England’s largest scenic reserve. However, her ideas about how the land should be managed were often nostalgic or paternalistic. She refused, for example, to add gas lighting or indoor bathrooms to any of her properties, as the following article details: Keith Thomson, “Beatrix Potter, Conservationist,” American Scientist 95, no. 3 (May–June 2007), https://www.americanscientist.org/.

[24] Rosa Bonheur is a noteworthy exception.

[25] Etheridge, “Maria Sibylla Merian: The First Ecologist?,” 35.

[26] Letter from Mary Symonds to Hester James, Madras, February 7, 1803, British Library, India Office Records, Mss.Eur.C.240/2, ff. 107r–110v.

[27] Donna Haraway, When Species Meet, Posthumanities, vol. 3 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 21.

[28] Vera Norwood, Made from this Earth: American Women and Nature (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1993), xvi.

[29] Emma Marris, Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World (New York: Bloomsbury, 2011).

[30] I’m thinking here of Timothy Morton’s book Ecology without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009); and of William Cronon’s essay, “The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature,” Environmental History 1, no. 1 (1996): 7–28.

[31] Paul Kingsnorth, “Dark Ecology: Searching for Truth in a Post-Green World,” Orion Magazine, 2012, https://orionmagazine.org/. There’s plenty in this article that I don’t relate to, but Kingsnorth’s definition of wilderness has stuck with me.