Near East to Far West: Fictions of French and American Colonialism

Reviewed by Alex ZivkovicAlex Zivkovic

Columbia University

Email the author: az2527[at]columbia.edu

Citation: Alex Zivkovic, exhibition review of Near East to Far West: Fictions of French and American Colonialism, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 2 (Autumn 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.2.23.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Near East to Far West: Fictions of French and American Colonialism

Denver Art Museum

March 5–May 29, 2023

Catalogue:

Jennifer R. Henneman,

Near East to Far West: Fictions of French and American Colonialism.

New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023.

288 pp.; 150 color and b&w illus.; selected readings; exhibition checklist; index.

$65 (hardcover)

ISBN: 9780300266047

Orientalism can refer to any number of representations of Near Eastern cultures across literature, philosophy, and (of course) painting. In the visual arts, French Orientalism is often seen as a coherent enough subset of paintings to be described and taught as a movement. This corpus of images is nonetheless diverse, including ethnographic portraits, architectural scenes, biblical stories, desert landscapes, and images of wild animals. At the Denver Art Museum, this nineteenth-century tradition is paired with a distant—yet surprisingly similar—set of paintings made in the US Southwest around the same time. Near East to Far West: Fictions of French and American Colonialism reveals direct influences between the French Orientalist school and US painters. Having established the fact of circulation of ideas and artists between these two areas, it further focuses on the colonial ideologies undergirding the images made in both occupied regions. Most of the galleries are organized around specific tropes shared between the two traditions like portraiture or desert scenes (fig. 1), producing a convincing account of how imperial ideologies function in art.

The exhibition and catalogue address directly the complicated questions surrounding intercultural contact, exploitation, and violence that Orientalism inevitably raises. Even the subtitle of the show calls attention to the colonial condition in which this art was made. The catalogue wisely follows an interdisciplinary approach that wrangles with different ways to account for the history and legacies of these images. Following an introductory essay by the curator Jennifer R. Henneman, the catalogue’s twelve essays traverse the intersecting fields of art history, history, native studies, and literature. Each essay roughly corresponds to a gallery of the exhibition. The exhibited artworks function as a nucleus around which the authors produce a network of related material, including nineteenth-century novels, contemporaneous visual images, and even twenty-first-century art. In addition to raising new questions, the catalogue successfully expands upon things mentioned in the wall labels, such as bison hunting or colonial settlements, developing them in well-researched and thoroughly documented essays.

The exhibition and catalogue participate in a wider art historical project that emphasizes transatlantic conceptual and material connections. This strategy has recently been adopted in other venues. For example, the editors of a special section of American Art focusing on race decided that the subject could only be properly treated by including artists and issues on both sides of the Atlantic. The introduction of that section notes that, though it may seem surprising to discuss Brazilian, Dutch, Andean, and Taíno art alongside art of the United States, doing so “locates North American art within a complex network of transnational negotiation.”[1]

Other recent projects have told the history of France and the US Southwest together. Most notably, Emily C. Burns’s Transnational Frontiers: The American West in Fin-de-siècle France (2018) explored how indigenous performers and exhibitions came from the United States to France (and Burns herself was an advisor to the exhibition and also contributed an essay on the same topic to the catalogue). The Rosa Bonheur exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay and Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux (2022–23) similarly addressed connections between Bonheur and Buffalo Bill.[2] In the Denver exhibition, this history of exhibiting Native Americans and cowboy performances is present in a room showing artifacts from the various Parisian Expositions universelles and the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, where these events occurred.

In addition to these moments of direct encounter, most of the galleries reveal visual similarities between the two traditions. Near East to Far West explores what a study of French-US networks might add to our understanding of both art making and empire building.[3] By positioning these objects in relation to actual colonial expansion—rather than just exoticism—the show embeds these objects in specific, often violent, histories. It picks up themes introduced in Linda Nochlin’s “The Imaginary Orient,” a sharp critique of dehistoricized, apolitical definitions of Orientalism in the visual arts first published in 1983 (and an essay frequently cited in the catalogue).[4] The Denver exhibition situates artworks as active agents in colonial processes. Beyond unpacking problematic sexual fantasies or racial myths, it proposes that art can shape public opinion by depicting people, animals, and lands in ways that supported driving colonial ideologies about white civilization and Manifest Destiny.

The formal qualities of individual objects are essential to the organization of the show. The first room (fig. 2), for example, compares two paintings that each show an older man, wrapped in large swaths of light cloth, standing in front of a building. The comparison calls attention to the similar dress and styles of different indigenous cultures adapting to desert climates in the Southwest and Near East. Furthermore, both paintings are by Gerald Cassidy (1869–1934) (his Cui Bono? from ca. 1911 and Midday Sun, North Africa from the 1920s), thus foregrounding the idea that it was not simply Orientalist strategies that were transnational in this period: artists themselves circumnavigated the globe. These works capture the gravitas of older men in an honorific way that also—intentionally or not—fits into a eulogizing, ethnographic accounting of “disappearing” races. With a single pair, the exhibition introduces numerous key themes and reveals the subtle, slippery interpretative frames surrounding all representations made in colonial conditions.

Several other rooms are structured around similarly compelling comparisons. In the following gallery, there is the Orientalist trope par excellence of the odalisque in the pairing of Charles Marion Russell’s (1864–1926) Keeoma [No. 1] (fig. 3) and Frederick Arthur Bridgman’s (1847–1928) An Oriental Beauty (fig. 4). The background wall shows a photograph of a similar scene, expanded to fill the wall. There are almost no similarities between the women other than their dark hair and jewelry, and yet they are all posed in extremely similar ways precisely because they are made to conform to a trope famous within Western painting. The theme of the reclining body is addressed wonderfully in a catalogue essay by Robert Warrior (Osage), extending the exhibition’s analysis of the female trope to also analyze male nudity and the way it participates in this tradition.[5] Entitled “Adam or Odalisque?: Or, the Recline of the West,” his essay traces the subject of the male nude forward into contemporary art with some projects that remediate art historical precedents by Michelangelo (1475–1564) and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) through a native lens, as well as other indigenous artworks that are completely uninterested in addressing Western precedents.

The show tries throughout to illuminate the underlying reasons that explain why two cultures so distant from one another were represented so similarly. If colonialism transformed the landscapes, built environments, and cultures of the places it went, artists prepared the ground. In rendering animals savage, they made way for their taming. In calling people “wild” in their titles, they paved the way for the French civilizing mission and the horrific history of boarding schools across North America. Visual tropes make unfamiliar spaces and people legible in ways that support and propagate patriarchy, white supremacy, and Manifest Destiny.

The subsequent rooms focus on specific case studies and topics. A section that pairs artists is the most biographical of the exhibition and presents Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) and Alfred Jacob Miller (1810–74) as one duo and Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) and George de Forest Brush (1855–1941) as another. Despite the fact that Gérôme was Brush’s teacher, their work is no more similar than the other artworks paired in the show, which perhaps emphasizes this exhibition’s point that the French Orientalist influence was pervasive. Miller’s small works on paper are not particularly visually interesting, though the complex histories of gender roles and indigenous marriage ceremonies they record are examined in a detailed essay by Scott Manning Stevens (Akwesasne Mohawk) entitled “Looking at Miller Looking at Indians” (likely a riff on Zig Jackson’s [b. 1957; Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara] photo series Indian Photographing Tourist Photographing Indians from the 1990s—coincidentally on display in another gallery).

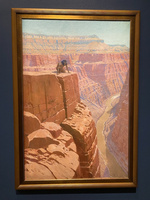

The more thematic rooms force us to consider how certain iconographies participate in longer art historical traditions and far-reaching colonial imaginaries (and, in my opinion, feature more exciting visual conversations than the biographical room). Paintings of the desert, for example, are inflected both by its perceived danger and its historical and biblical resonances in Western tradition. One of the standout works on this subject is Fernand Lungren’s (1857–1932) In the Abyss: Grand Canyon (fig. 5). In her introduction, Henneman explores how this scene ironically effaces railroads and other signs of modernity despite the fact that Lungren’s work was funded by the Santa Fe Railway. Lungren’s painting participates in a tradition of the sublime that is often understood to honor nature; however, the painting also empties the landscape and poses an indigenous person as if they are the sole—perhaps last—inhabitant of the space. This combination of respect for nature with disrespect for indigenous cultures, together with the obfuscation of white, Western harm to people and landscapes, is packaged into an undeniably gorgeous painting of a gorgeous place.

A less obvious Orientalist subject is animals, but, as the exhibition convincingly demonstrates, there are multiple colonial myths embedded in a painting like Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Night in the Desert (fig. 6). The tigers appear to be the sole inhabitants of a picturesque, empty desert. Gérôme’s lion and tiger studies have a quiet nobility despite the fact that the creatures he paints are trapped, imperial bounty encountered in Paris. A wall label for this room with the heading “Big Cats & Bison” notes this discrepancy by calling attention to the fact that zoos are spaces of contact and conquest. Animaliers, they say, “metaphorically liberat[ed] these animals in imagined landscapes,” freeing them from zoos and using landscape scenes to return them to their native habitats. Furthermore, the picturesque landscape they are placed into is a subject that many scholars have discussed as enabling and encouraging colonial conquest.[6] The lions are thus already trophies of conquest as well as props for a picturesque landscape scene that promotes further settlement. Though capturing the beauty of these creatures and places, Gérôme’s painting is a byproduct of the ongoing “taming” of animals and environments.

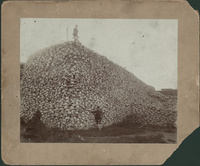

As the wall label further explains, control over animals was also about control over people. The biopolitical management of nature had direct effects on local peoples, as, for example, in the attempted extermination of bison in North America. The label mentions this complex history, stating that bison were “a symbol of the nation that nearly caused their extinction in an effort to control the indigenous populations who relied on them.” The hunting scenes suggest the deep connection between indigenous populations and bison, which is contrasted directly with the brutal history of their near extinction at the hands of settlers. In the galleries, there is a sculpture of an indigenous bison hunt and a painting of a herd of bison seemingly alone in the wild. The latter, William Jacob Hays’s (1830–75) Herd of Buffalo (fig. 7) is calm and idyllic, with a large group of bison gently roaming in the morning light. That illusion of seemingly untouched nature, however, is dramatically shattered as it is paired with a wall-sized enlargement of an anonymous 1892 photograph of a pile of bison skulls (fig. 8) that foregrounds the slaughter of animals whose species was near extinction. A video produced by the Fort Peck Indian Reservation was placed over the mural, foregrounding both human connections to bison and ongoing efforts to rehabilitate the species. The catalogue also includes a similar juxtaposition that reveals this darker history. Christine Garnier’s essay on animal imagery in the catalogue includes a horrifying photograph by Laton Alton Huffman (1854–1931) showing several dead bison from circa 1878 (fig. 9). It bears a title that emphasizes the speed of mass slaughter: Five Minutes Work—Buffalo Cows.

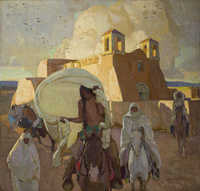

The final gallery looks at the artist community that formed in Taos, New Mexico, tracing this French Orientalist tradition as it extended into the twentieth century. Artists in Taos began to adopt a more modernist, flat style, but similar patterns of appropriation of indigenous cultures remained. This room is a fitting conclusion because these flattened paintings are a dramatic departure from the detailed gilding or intricate ornamentation seen in paintings in the first rooms. When one imagines paintings by earlier Orientalists like Gérôme or Delacroix, it is those ornate features that are conjured, but these tropes and techniques fall away in these later works. The curatorial placement of Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant’s (1845–1902) Evening on the Seashore—Tangiers (fig. 10) in the Taos gallery offers a sense of transition between the two different eras of Orientalism. It includes traces of that earlier, hyper-detailed approach in the ornamentation of the plate, rug, and necklaces of the central woman, but there are also vast swaths of smooth paint in the sky, ocean, building, and cloth that portend the Taos approach exemplified in a work like Ernest Blumenschein’s (1874–1960) Church at Ranchos de Taos (fig. 11).

Photography as a tool of painting also makes an appearance in the Taos gallery. Various photographs depict Ben Lujan (n.d.) and Jerry Mirabal (n.d.) posing for painters Joseph Henry Sharp (1859–1953) and E. Irving Couse (1866–1933). They look uncomfortable as they assume unnatural postures. One photograph is even covered by a grid—an artist’s technique that unintentionally evokes the uncomfortable history of ethnographic and physiognomic portraiture that used grids as backdrops for standardizing photographs. Their awkward stiffness similarly recalls the paintings such as Gérôme’s Snake Charmer (1879), so brilliantly described by Nochlin: “taxidermy rather than ethnography seems to be the informing discipline here: these images have something of the sense of specimens stuffed and mounted within settings of irreproachable accuracy and displayed in airless cases.”[7] By bringing in photographs that show the conditions of the studio, the curatorial team helps make tangible the potentially fraught interactions between artists and their models. As in recent exhibitions like Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today at the Wallach Gallery (2018–19) and its French counterpart La Modèle noire, de Géricault à Matisse at the Musée d’Orsay (2019),[8] this exhibition foregrounds the interaction between white artists and non-white models. As is often the case, many of the figures who posed for paintings in other galleries unfortunately remain anonymous. When the models are forgotten, debates about the ethics of depicting other cultures can shade into abstractions around general issues of appropriation. Here, the representations of named people force us to reflect on these models’ lived realities more viscerally.

Another question that lingers at the end of the exhibition evokes a query that Nochlin foregrounded in her 1983 critique: what is the real colonial history behind the art? The exhibition texts frequently invoke violence, but little information about the displacement of peoples, violence of colonial wars, or actual patterns of settlement are featured in the gallery. The catalogue, fortunately, provides such information, as in a detailed chronicle of Algerian governance by historian Jennifer E. Sessions. A similar essay on the Southwestern context would have been welcome. In the gallery itself, timelines and demographic numbers could better ground that history, but—more fittingly for an art exhibition—so could reproductions of visual documents like maps or even paintings that capture urban development in an almost documentary mode, like Jean‐Charles Langlois’s (1789–1870) Panorama of Algiers (1833). This exhibition goes further than most in invoking the material realities of colonial power, but it would be helpful to feature visual artifacts that directly speak to how these regions were managed and controlled, rather than sometimes leaving empire as an abstraction.

The ethics of exhibiting images produced within extremely unequal power dynamics is another issue foregrounded by this show. Inequity occurs not only in individual relations between artist and model but also in the violent state operations that allowed artists to visit these occupied regions and produce such works. In response to these ethical debates, scholars sometimes choose not to reproduce violent images, especially images of the deceased or racist caricatures, preferring this strategy to the possibility of reinscribing or reproducing harmful or hurtful ideas. More ambiguous cases of indirect violence have been redistributed and then fairly critiqued for propagating visual exploitation which had long undergirded sexual violence in enslaved and colonial conditions—as in the backlash that recently greeted the book Sexe, race, et colonies in France.[9] On the whole, however, the museum obviously sees value in exhibiting Orientalist images, as they are the substance of this exhibition. Through thoughtful juxtapositions, contextualizing materials, and other activities related to the exhibition, the curatorial team had sought to address the problematic aspects of these objects and to speak to issues of diversity and inclusion.

At the end of the show, a sign guided visitors to another exhibition, Speaking with Light: Contemporary Indigenous Photography (February 19–May 22, 2023), on the floor below for further explorations of indigenous representation. Curated by John Rohrbach from the Amon Carter Museum of American Art and Will Wilson (Navajo/Diné), this exhibition featured work from over thirty indigenous photographers. The two exhibitions address shared themes of indigenous relationships to place but approach the material very differently. Near East to Far West: Fictions of French and American Colonialism is about the cross-pollination of art historical traditions in an age when colonizing practices cross-pollinated between two geographically disparate regions. By contrast, this focus on Western art history is almost entirely absent from the photography show; there are no remixes of Western art historical references in any of the photographs or collages in the style of Kent Monkman (b. 1965, Cree). Instead, the photographs span a range of topics sparked by the artists’ indigenous identities, including spiritual documents and images addressing the historical effects of racism. I flag this not to advocate for artists or exhibitions focused on one mode or the other, but to emphasize the differing approaches. After an exhibition full of ambiguous, often uncomfortable, presentations of indigenous people, it was refreshing to see indigeneity represented and celebrated by indigenous people themselves. For example, in mixed media works by Sarah Sense (b. 1980, Choctaw and Chitimacha), historic colonial maps are interwoven together with photographs—bringing settler documents into indigenous history and then critiquing them from an indigenous point of view.

The activities that the Denver Art Museum sponsored to bolster the critique of Orientalism in Near East to Far West included scholarly commentary and community feedback centering the views of people of indigenous North American and Near Eastern descent. Funded in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, these responses and the processes that elicited them are transparently documented on the museum’s blog.[10] In the galleries and an accompanying online exhibition guide, “Community Voices” feature both scholars and focus group participants who respond to the artworks.

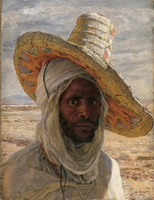

In focus groups, some local people presented their personal stories. Mariam Hama from Aurora, Colorado, noted, for example, a rug in the painting which prompted her to ask: “How can we tell what is based on fantasy in these paintings?” Indeed, many art historians face this very challenge, as, for example, in japoniste paintings showing collections of Japanese objects or work by Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) that appropriates Oceanic motifs. Even “authentic” objects pass through the painter’s eyes, hands, and tools, which can further distort our perception of them. In other moments, the community voices defend the poignancy of the artwork in the exhibition, as in a comment about John Singer Sargent’s (1856–1925) Egyptian Woman (fig. 12): “I am from Egypt, and for me, this is one of the few images, or portrayals, in the exhibition that doesn’t seem obviously filtered through an Orientalist imagination.” This respondent captures the difficulty of separating stereotypes from sympathetic and discerning portrayals of individuals. Nearby, a wall label raises a similar issue, asserting that Homme au Grand Chapeau (Man in a Large Hat) (fig. 13) by Nasreddine (Alphonse-Étienne) Dinet (1861–1929), is a “psychologically poignant portrait.” As a method of curatorial framing, this plurality of voices both strengthens some of the exhibition’s main narratives and presents issues for future scholarly inquiry. For example, in his catalogue essay and in a wall label, Robert Warrior notes Blackness’s presence in French Orientalism and its absence in images of the West.

Supplementing the nineteenth-century paintings, the exhibition also featured a contemporary installation by Dana El Masri (b. 1987), a multimedia artist of Egyptian Lebanese descent trained as a perfumer. In this “reflection zone” inside the galleries, visitors could open the lids of boxes that contained two different scents, entitled “Sarab” and “Hawa” (“mirage” and “air/wind/longing,” in Arabic).[11] Composed of notes of cedar, amber, and various spices, the perfumes were complex and—like the paintings—incorporated numerous references to distinct cultures. El Masri stated that she hopes to use smell to guide people towards “a narrative closer to reality and away from colonial fantasy.” Unfortunately, the relation between Orientalism’s visual and olfactory traditions was not clearly articulated by the curatorial team. Though scents can also fall into tropes, amidst visual objects (and for visitors like myself more familiar with visual traditions), more guidance would be welcomed about the history of exoticism in perfumes. Similarly, it was a missed opportunity to not directly connect these scents to the “recreated” ethnographic villages that were part of the world’s fairs system in the nineteenth century, where visitors could eat and drink Near Eastern cuisines.

Another commissioned work combined poetry and video and, by contrast, related more directly to the themes of the exhibition. The video project Us (2023) was a collaboration between poet Jennifer Elise Foerster (b. 1979, Mvskoke), who wrote the text, and visual artist Steven Yazzie (b. 1970, Navajo/Laguna Pueblo), who used AI to make the video. The online description notes the potentially thorny issues raised by AI usage, but its inherent technological transmutation of existing artworks feels like an apt metaphor for Orientalism’s own appropriations.[12] After all, it was not just that Orientalist artists responded to the tropes of earlier paintings, but also that they incorporated indigenous pottery, jewelry, and other decorative arts into their paintings, a form of plunder in paint. The text of the poem evokes a sense of mourning over historic losses that acknowledges these nineteenth-century histories. Crucially, it also points to climate change today with references to a river “now dried, which means dead,” evoking drought, which is a subject uncomfortably familiar in the Southwest today. The imagery in the video directly evokes the visual repertoire of the galleries including empty deserts, bison, tiger-like forms, and robed dancers. Remixing images from the past with an uncanny, science-fiction sensibility, the video shows us an uncertain—possibly even uninhabitable—future.

The curatorial team of Near East to Far West encouraged visitors to see the indigenous photography show, but in the permanent galleries there were also unannounced pairings of works that raised similar issues. Henneman supervised the rehanging of the Western American Art galleries in the Denver Art Museum’s Martin Building, which reopened in 2021, with explicit attention to telling more diverse histories about race, gender, and ecologies. The special exhibitions and permanent galleries covered shared ground. For example, in the Western American Art galleries, there is a beautiful pairing of two sensitive portraits of indigenous individuals (fig. 14)—Homer Boss’s (1882–1956) Koh-tseh (Yellow Buffalo) (about 1931) and Andrew Dasburg’s (1887–1979) Bonnie (1927). The titles of these portraits record the names of their sitters, who thus differ from the often-anonymous figures featured in Near East to Far West, but they raise similar questions about the relations of artists to subjects, especially under occupied conditions.

The Western American Art galleries also highlight a major omission from Near East to Far West: the almost total absence of white figures. The permanent collection features a range of early works celebrating—and later works interrogating—the figure of the cowboy (fig. 15). A masculine, often white archetype of the colonial frontier of the United States, the cowboy played a significant role in the self-image of both white settlers and white citizens watching westward expansion from afar. In Near East to Far West, by contrast, there is only one painting of a white subject, the cowboy in Frederic Remington’s (1861–1909) Only Alkali Water (fig. 16). Besides representations of Buffalo Bill and other performers in the display of fairground ephemera, the paintings of North Africa and the Southwest in the exhibition focus solely on indigenous inhabitants or depopulated landscape scenes. Even Speaking with Light dealt directly with making legible the whiteness that stood behind many representations of indigeneity. For example, Zig Jackson’s series Indian Photographing Tourist Photographing Indian (1990s) is a set of photographs capturing precisely the dynamic described by the title. The white people wielding a camera participate in the same tradition as the Orientalist painters. Jackson too now wields a camera to depict the very act of voyeurism.

The cowboys and tourists in the work from the permanent galleries made evident that an interrogation of whiteness could have offered a powerful conclusion to Near East to Far West. Even if images of settlers are often not included in the canonical Orientalist corpus, they offer a more complete picture of colonialism. If the exhibition is about the fictions of colonialism, then we need to show the “writers” and omissions of that story too. Doing so would interrogate the so-called “unmarked” identity, rather than just considering the race of Orientalism’s non-white subjects. “Whiteness,” an ascendant critical term in art history,[13] appears just once in the catalogue as a reference to identity. That said, the other spaces in the museum provoked this reflection on whiteness, showing how powerful it can be to thoughtfully re-stage permanent collections (as the Denver Art Museum has so successfully done) and how productive it can be to have two resonant exhibitions overlap on the calendar.

Overall, Near East to Far West was an important, visually stunning contribution to studies of US art and French Orientalism. It successfully demonstrates patterns of influence between these two important corpuses, but it also speaks to larger questions of colonialism and identity that reverberate beyond the visual material into the founding myths of empire.

A correction was made on November 7, 2023: an earlier version of this review stated that there was not a photograph of industrial bison slaughter in the gallery titled “Big Cats & Bison.”

Notes

[1] Nika Elder, Catherine Roach, and Daryle Williams, “Art Institutions and Race in the Atlantic World: 1750–1850,” American Art 36, no. 2 (Summer, 2022): 2.

[2] Verónica Uribe Hanabergh, exhibition review of Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899), Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.1.20.

[3] This exhibition also resonates with work outside of art history. Its driving force is closely aligned with Arid Empire: The Entangled Fates of Arizona and Arabia (2022) by geographer Natalie Koch. In her account of agricultural science in the United States and the Middle East, Koch reveals how networks of desert experts moved between the two regions in order to help various governments wield agricultural knowledge as a means to exert control over territories.

[4] Linda Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient,” in The Politics of Vision: Essays on Nineteenth-Century Art and Society, first edition, Icon Editions (New York: Harper & Row, 1989), 33–59.

[5] The catalogue and wall labels of the exhibition identify the nation or tribe of Native American authors, a practice we have kept in this review.

[6] W. J. T. Mitchell, “Imperial Landscape,” in Landscape and Power, ed. W. J. T. Mitchell (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 5–34; Philippa O’Brien, No Stone Without a Name: A Visual History of Possession and Dispossession in Australia’s West (Ellenbrook: Ellenbrook Cultural Foundation, 2022); John Zarobell, Empire of Landscape: Space and Ideology in French Colonial Algeria (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010).

[7] Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient,” 10.

[8] Adrienne L. Childs, exhibition review of Le Modèle noir de Géricault à Matisse, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 18, no. 2 (Autumn 2019), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2019.18.2.18.

[9] Pascal Blanchard, Nicolas Bancel, et al., Sexe, race et colonies (Paris: Éditions La Découverte, 2018). The prominent feminist group Cases Rebelles condemned it in a manifesto: Cases Rebelles, “Les corps épuisés du spectacle colonial,” CASES REBELLES (blog), September 2018, https://www.cases-rebelles.org/. For a summary of this controversy, see Priscille Lafitte, “‘Sex, Race & Colonies’ Book Hits Nerve in Post-Colonial France,” France24, October 22, 2018, https://www.france24.com/.

[10] JR (Jennifer R.) Henneman, “New Exhibition Presents Diverse Perspectives,” Denver Art Museum (blog), March 27, 2023, https://www.denverartmuseum.org/.

[11] Carleen Brice, “Q&A with Perfumer Dana El Masri,” Denver Art Museum (blog), March 23, 2023, https://www.denverartmuseum.org/.

[12] Eric Berkemeyer, “Video Uses Artificial Intelligence to Reconsider Artwork,” Denver Art Museum (blog), March 13, 2023, https://www.denverartmuseum.org/.

[13] Most recently Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby demonstrates how biological conceptions of race—including whiteness—were destabilized by the diverse connotations of “Creole” identity, which could be applied to someone of mixed-race parentage but also to someone whose family had lived in colonies. Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Creole: Portraits of France’s Foreign Relations during the Long Nineteenth Century (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2022). On the topic of whiteness in the American Southwest, see Alexis Monroe, “Whiteness and the West before the Transcontinental Railroad,” American Art 36, no. 3 (Fall 2022): 28–32.