New DiscoveriesFrançois-Auguste Biard, Bust-Length Study of a Man, ca. 1848

by Baptiste Henriot

Baptiste Henriot

Author of the catalogue raisonné of François-August Biard

Email the author: francoisauguste.biard[at]gmail.com

Citation: Baptiste Henriot, “François-Auguste Biard, Bust-Length Study of a Man, ca. 1848,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 2 (Autumn 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.2.7.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

In November 2021, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York acquired a bust-length oil sketch of a young Black man (fig. 1).[1] Formerly attributed to Théodore Géricault (1791–1824), the painting was long thought to be a study for his famous Le Radeau de la Méduse (The Raft of the Medusa) of 1819, but recent research has convincingly shown that it was painted by François-Auguste Biard (1799–1882), an artist eight years younger than Géricault. Mostly forgotten after his death until the 2020–21 exhibition at the Maison Victor Hugo in Paris and a simultaneous exhibition in Tromsø, Norway (both reviewed in this journal),[2] Biard was a successful artist in his time, though few critics would have characterized him as a “genius.” “The name of M. Biard does not evoke the name of a great master,” wrote Jules-Antoine Castagnary (1830–88) in 1861. “His work raises no question of aesthetics. M. Biard stands alone in contemporary painting, without ancestors, and probably without posterity. He is neither the first nor the last artist of his time. Thanks to a unique character, he has made a unique place for himself.”[3]

Biard was born on June 29, 1799, in Lyon, France. His mother, who desired an ecclesiastical career for her only son, apprenticed him as a clerk to an abbot in the region.[4] But Biard soon rebelled and decided instead to study at the École des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts) in his hometown. He worked in the ateliers of Pierre Révoil (1776–1842) and Fleury François Richard (1777–1852), where his natural talent was appreciated. When he was barely fifteen years old, he won a first prize in drawing, and his teachers predicted he would have a fine career as a painter. Little by little, Biard moved away from the “troubadour” style of his teachers, preferring the art of younger artists like Géricault, whose deathbed portrait he painted,[5] to focus on scenes from contemporary life. In 1824 he sent his first submission to the Paris Salon, and between that year and 1882 he participated in almost every Salon as well as in numerous provincial exhibitions, showing paintings on a wide variety of subjects, including genre scenes, historical events, seascapes, portraits, and landscapes. In total, he exhibited nearly 170 paintings, which were popular with the viewing public.

Meanwhile, Biard traveled frequently. In 1825, he went to Rome in the company of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875) to complete his artistic education. Two years later, he joined the French navy as a drawing teacher aboard a training corvette and toured the Mediterranean basin for about a year.[6] Travels to Great Britain and across Western Europe followed. During the summer of 1839, he was invited to take part in a scientific expedition to explore part of Spitsbergen, a large island bordered by the Arctic Ocean, the Norwegian Sea, and the Greenland Sea. There he painted numerous polar landscapes as well as genre scenes featuring the Sami, the Indigenous people of Lapland.[7] When shown at the Salon of 1841, Biard’s Spitsbergen paintings drew huge crowds. So successful were they that he was commissioned by King Louis-Philippe (1773–1850) to paint a series of large paintings for the Musée Historique in Versailles, recording the king’s visit as a young man to Lapland in the summer of 1795.[8]

Between 1841 and 1848, Biard was at the height of his success. Though he was not a favorite of all critics, the public loved his work and flocked to the Salon to see his paintings. In addition to his spectacular “ethnographic” pictures, they admired his burlesque paintings of life in France, such as his undated Chute à la sacristie (Fall in the Sacristy),[9] in which a priest has just fallen, dead drunk, on his way to the altar; or his undated Surprise du halage (Surprise Hauling),[10] representing the surprise (and unwanted) rescue of a bourgeois couple bathing in the Seine River.

With the abdication of King Louis-Philippe in 1848, Biard lost his protector and his popularity. But he continued to paint relentlessly and to present his works at the annual Salons. In April 1858, still eager for adventure, Biard decided to leave for Brazil. This trip, which was initially planned to last two or three months, would take two years. Upon his arrival in Rio de Janeiro, Emperor Pedro II (1825–91) invited the artist to his palace and asked him to paint numerous portraits of his entourage.[11] Biard was even offered the directorship of the Academia Imperial de Belas Artes (Imperial Academy of Fine Arts), a post he refused. After six months in Rio, Biard embarked on a trip into the Amazon rainforest. After a first foray into the forest in the province of Espiritu-Santo, he reached the Amazon River, traveled up to Manaus, and then explored the Rio Negro in a small canoe before ending his journey on the banks of the Rio Madeira, in Mundurucu territory. Biard returned to France tired and ill, with nearly twelve hundred drawings,[12] some photographs on glass plates, and many objects (such as adornments, headdresses, and weapons). He also had serious financial problems, which forced him to sell most of his paintings in two auctions.[13] He died in 1882, carried away by a mysterious disease probably contracted in Brazil, and was forgotten soon after his death. His burlesque paintings no longer seemed funny; his landscapes of faraway regions came to be seen as too fanciful.

Biard and the Slave Trade

One aspect of Biard’s work not touched upon thus far is his representations of the slave trade, a recurring subject in his paintings. During his Mediterranean voyage in 1828, he was confronted for the first time with the trade in humans on the coast of North Africa. He submitted a large canvas entitled La Traite des nègres (The Slave Trade) to the Salon of 1835 (fig. 2), now in the Wilberforce House Museum in Hull, United Kingdom, where it is titled Slave Trade (Slaves on the West Coast of Africa). A critical success in its time, the painting represented the entire process of the slave trade in a single image, possibly inspired in part by paintings such as Slave Trade (Execrable Human Traffick, or the Affectionate Slaves) (ca. 1788–89) by George Morland (1763–1804), which was widely reproduced in prints (fig. 3). The French abolitionist, journalist, and politician Victor Schoelcher (1804–93) described Biard’s painting in glowing terms:

This faithful account of an appalling trade is energetic and striking. On the right lounges the slave captain, the trader in negroes, his register before him. He supervises the checking of the merchandise. Two sailors hold down a black man stretched out at his feet; one presses his throat to force him to open his mouth, so as to judge by his teeth if he is young; the other strikes him on the chest, to find out if his lungs are good. Next to the slaver sits a black prince, who smokes with the most unflappable coolness. No doubt it is he who sells his prisoners for a few barrels of brandy or fifty of those bad guns that are called Gisquet guns, to shame the man who bears that name. Further on, children are violently torn from their mothers; to the right, the men and women bought are branded with a hot iron with the brand of the ship’s cargo; finally, in the background, one sees throngs of negroes, still bound to large beams and herded forward with strong lashings, awaiting the examination that will condemn them to the most brutalizing slavery, unless they are lucky enough to be consumptive. Such is M. Biard’s picture; it is a lively and painful scene which fills you with profound pity; it is one of the finest arguments that has been made against the slave trade. M. Biard has put a lot of soul and talent into it. His painting has vigor, and our only regret is that the picture is a little dark in color and its composition jumbled. It doesn’t have sufficient unity to grab your attention all at once; the episodes are not all linked together perfectly: one has to look for them one after the other.[14]

Schoelcher’s praise of the picture as a “lively scene” has much to do with the carefully observed details of the painting’s paraphernalia—carpets, pipes, mats, whips, branding irons, and so on. Biard’s interest in material details may be related to his activity as a collector of objects and curiosities picked up on his trips. The catalogue of a sale of the contents of his workshop, held in 1865, lists an iron yoke, a pair of handcuffs, ties to tighten the forehead, and whips, objects that are found in several of his works, notably in his Slave Trade (see fig. 2).

In 1848, after the July Revolution that gave rise to the Second Republic, the new minister of the interior, Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin (1807–74), acquired a monumental canvas from Biard[15] to commemorate the recent abolition of slavery in the French colonies (April 27, 1848), a measure in which he as well as Schoelcher had played a crucial role. Entitled L’Abolition de l’esclavage dans les colonies françaises (The Abolition of Slavery in the French Colonies) (fig. 4) and exhibited at the Salon of 1849, the painting was widely admired in its time and has remained so, as it is commonly reproduced in French history textbooks. Biard brought together in this painting both masters and slaves, united by a feeling of joy and brotherhood that belied reality. On the right, dressed in white, the ancient masters receive thanks from an ancient slave who is still on her knees and half naked, while in the center two former slaves celebrate the decree that Schoelcher, on the left, has just pronounced.

While Biard’s scene of a joyful reconciliation between masters and slaves appears improbably idealized, it does reflect the high-minded language of the abolition decree, written under the supervision of Schoelcher, who presided over the Second Republic’s Commission for the Abolition of Slavery.[16] Language in that decree, such as “slavery is an attack on human dignity” (l’esclavage est un attentat contre la dignité humaine) and “[slavery is] a flagrant violation of the republican dogma: ‘Liberty, Equality, Fraternity,’” (une violation flagrante du dogme républicain: “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité”), seems to have been at the root of Biard’s conception of the painting.

On his return from Brazil in 1860, Biard came back to the theme of slavery with a series of three paintings detailing different stages in the life of a slave: capture, sale, and escape.[17] That these paintings were well known in their time is suggested by the fact that the German-born American artist Theodor Kaufmann (1814–96) closely paraphrased one of Biard’s scenes (fig. 5) in a work called On To Liberty (fig. 6), transposing the scene from Brazil to the United States.

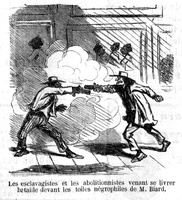

The travelogue illustrated with 180 engravings after his sketches (fig. 7) that Biard published in 1862, two years after his return from Brazil,[18] follows his wanderings through a country where slavery would not be abolished until 1888. His remarks on the slaves he met during his trip are often ambiguous by today’s standards. He writes, for example, that Brazil is the “country where they [the slaves] are . . . the least unhappy.”[19] But the illustrations often appear sympathetic to the fate of slaves. The French critic Théophile Gautier (1811–72), in his review of the Salon of 1861, wrote that Biard’s paintings would make “magnificent abolitionist vignettes.”[20] The caricaturist Cham (1818–79) also seems to have shared this opinion, evidence for which is his engraving for Le Charivari picturing a slaver and an abolitionist engaged in a battle in front of one of Biard’s canvases (fig. 8).

Biard’s Bust-Length Study of a Man

Biard’s Bust-Length Study of a Man, recently acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (see fig. 1), may be related to The Abolition of Slavery in the French Colonies. The figure’s hunched back, distant gaze, and shaggy beard suggest that the painter made the sketch not as a portrait study but with a narrative painting in mind: the figure shows signs of a past marked by hard work and suffering, which would make it a suitable study for a painting dealing with slavery.

As mentioned, Bust-Length Study of a Man was long attributed to Géricault. Klaus Berger and Diane Chalmers Johnson have shown that Géricault painted numerous Black men and women, in studies as well as in finished paintings.[21] Indeed, one of the most famous representations of a human back in nineteenth-century French painting is that of the Black man in Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, a study for which is found in the Musée du Louvre in Paris (fig. 9). It is therefore not surprising that Biard’s study has been reproduced in various books,[22] hung in several exhibitions,[23] and sold (for the first time) at auction at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris in November 2017 as a work by Géricault.[24] The attribution to Géricault was first questioned in the March 1980 issue of The Burlington Magazine by art historian Lorenz Eitner, who did not, however, offer an alternative attribution.[25] Only recently was the work reattributed to Biard, on the basis of comparison with another study of the same model, known as Study of a Man with Broken Shackles (fig. 10). Though less powerful artistically, this second study more explicitly evokes slavery, as it shows the model, seated, dressed in a white shirt, with a pair of open handcuffs by his side. The year “1848,” inscribed at the bottom right, suggests that it is closely linked to the decree of abolition promulgated in that year.

Biard’s second study calls to mind The Captive Slave painted in 1827 by the British artist John Philip Simpson (1782–1847) (fig. 11). The model for this work was Ira Aldridge (1807–67), an American-born British actor and playwright, best known for his Shakespearian roles. It is possible that Biard knew of the British painting, which had been widely disseminated through engravings since 1827.[26] Whether or not it was inspired by Simpson’s painting, Biard’s Study of a Man with Broken Shackles was clearly painted from a live model, the same one who posed for the Metropolitan Museum of Art study. In all likelihood, it was a model Biard had recruited in Paris from among the small community of Black people who had come to the city from one of the French colonies in North Africa, the Caribbean, or Louisiana. In an article published in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide in 2022 (in which Biard’s study was reproduced), Susan Waller, an authority on nineteenth-century artists’ models in France, wrote that in the first half of the nineteenth century “there were a number of Blacks posing in Parisian studios, but the names and histories of these men and women are largely unknown.”[27] Indeed, as Waller shows, it is not until the second half of the century that contemporary interest in artists’ models led to increased knowledge about their names, ages, and backgrounds. We may never know the identity or the life story of the model who posed for Biard’s studies. But the two works do tell us something about the period in which they were painted—a time when slavery was still rampant in many parts of the world and Paris had become something of a haven for those who, no doubt with great difficulty, had escaped those parts in search of better lives.

Just as we cannot identify the model in Biard’s study, we also do not know Biard’s position on the issue of slavery, at least not through written sources such as diaries or letters. While it is undeniable that he is one of the few artists to repeatedly seize on the theme of slavery, he also, like many of his contemporaries, remained silent as to his position on the issue, and never, as far as is known, expressed himself in favor of, or against, abolition. Despite this ambivalence, Biard sided modestly and discreetly with convinced abolitionists such as Schoelcher and Victor Hugo (1802–85).

Notes

All translations, unless otherwise noted, are my own.

[1] The auction was held on November 9, 2021. See Maîtres anciens et du XIXe siècle: Tableaux, dessins, sculptures, auction cat. (Paris: Artcurial, 2021), 178, lot 122.

[2] France Nerlich, “François-Auguste Biard peintre voyageur and The Life of Others,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 20, no. 3 (Autumn 2021), https://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/.

[3] “Le nom de M. Biard n’éveille aucun nom de grand maître. Son oeuvre ne soulève aucune question d’esthétique. M. Biard se pose dans la peinture contemporaine, seul, sans aïeux, et vraisemblablement sans postérité. Il n’est ni le premier, ni le dernier artiste de son temps. Grâce à un caractère à part, il s’est fait une place à part.” Jules-Antoine Castagnary, Salon de 1861: Les Artistes au XIXe siècle, pt. 7 (Paris: Librairie Nouvelle, 1861).

[4] For a complete chronology of Biard’s life, see my website, François-Auguste Biard, which also contains a catalogue raisonné in progress, www.francoisaugustebiard.com.

[5] François-Auguste Biard, Géricault sur son lit de mort (Géricault on His Deathbed), 1824, private collection, France.

[6] For nine months, Biard gave lessons to apprentice sailors in order to teach them some drawing fundamentals.

[7] The Sami used to be referred to as Lapps, but that name, a Swedish pejorative that means “wearers of rags,” is no longer used today.

[8] François-Auguste Biard, Le Duc d’Orléans descendant la grande cascade de l’Eijanpaikka sur le fleuve Muonio (Laponie), septembre 1795 (The Duc d’Orléans Descending the Great Waterfall of the Eijanpaikka on the Muonio River [Lapland], September 1795), 1840, oil on canvas; and Le Duc d’Orléans recevant l’hospitalité sous une tente de Lapons, août 1795 (The Duc d’Orléans Receiving Hospitality in a Lapp Tent, August 1795), 1840, oil on canvas. Both works are located in the Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles.

[9] François-Auguste Biard, Chute à la sacristie (Fall in the Sacristy), undated, oil on canvas, Galerie Michel Descours, Paris, https://www.peintures-descours.fr/. The Galerie Michel Descours gives the painting the title Le Bedeau ivre (The Drunk Beadle).

[10] François-Auguste Biard, Surprise du halage (Surprise Hauling), undated, oil on canvas, Tomaselli collection, Lyon, https://tomaselli-collection.com/.

[11] These paintings are now in Brazilian public collections, notably the Pinacoteca and the Paulista Museum in Sao Paulo and the National Museum of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro.

[12] Only a dozen of these drawings are known to us today; most are lost and were sold in lots of several dozen or of hundreds during his workshop sales.

[13] The first sale took place at the Hotel Drouot in Paris from March 6 to 8, 1865, with 383 lots: paintings, sketches, objects brought back during travels (weapons, vases, objects related to slavery, musical instruments, and so on). The second took place on March 18, 1875, and only included about forty paintings.

[14] “Cette relation fidèle d’un exécrable commerce est énergique et saisissante. A droite est couché le capitaine négrier, le marchand de nègres, son registre sous les yeux. Il fait vérifier si la marchandise est bonne. Deux matelots tiennent un noir étendu à ses pieds; l’un lui presse la gorge pour le forcer à ouvrir la bouche, afin de reconnaître aux dents s’il est jeune; l’autre lui frappe sur la poitrine, pour savoir si le coffre est bon. A côté du négrier est assis un prince noir, qui fume avec le plus imperturbable sang-froid. C’est lui sans doute qui vend ses prisonniers pour quelques barriques d’eau-de-vie ou cinquante de ces mauvais fusils qu’on appelle fusils Gisquet, à la honte de celui qui porte ce nom. Plus loin, des enfants sont violemment arrachés à leur mère; vers la droite, on marque d’un fer rouge, à la marque de la cargaison du navire, les hommes et les femmes achetés; enfin, dans le fond apparaissent, conduites à grands coups de fouet, des bandes de nègres liés encore à de grosses poutres, en attendant l’examen qui doit les condamner à l’esclavage le plus abrutissant, s’ils n’ont le bonheur d’être poitrinaires. Tel est le tableau de M. Biard; c’est une scène vive et douloureuse qui vous pénètre d’une profonde pitié; c’est un des plus beaux plaidoyers qui aient été prononcés contre la traite. M. Biard y a mis beaucoup d’âme et de talent. Sa peinture a de la vigueur, et nous regrettons seulement que le tableau soit un peu terne de couleur et confus d’arrangement. Il ne vous prend pas par une assez grande unite d’ensemble; tous les épisodes ne se lient point parfaitement entre eux: il faut aller les chercher l’un après l’autre.” Victor Schoelcher, “Salon de 1835,” Revue de Paris, March–April 1835, 52–53. Translation by Nerlich, “François-Auguste Biard peintre voyageur and The Life of Others.”

[15] Though most sources on Biard state that the painting was commissioned, an official document to that effect has never been found. It is possible that Biard painted the work on his own initiative and that the government later bought it from him.

[16] For the full text of the decree abolishing slavery in the French colonies, dated April 27, 1848, see “Décret d’abolition de l’esclavage du 27 avril 1848,” Wikipedia (French), https://fr.wikipedia.org/.

[17] François-Auguste Biard, Emménagement d’esclaves à bord d’un négrier (Moving Slaves Aboard a Slaver), 1861, unlocated; Vente d’esclaves dans les États de l’Amérique du Sud (Slave Auction in the States of South America), 1861, unlocated; and Chasse aux esclaves fugitifs (Pursuit of Fugitive Slaves), 1861, unlocated.

[18] François-Auguste Biard, Deux années au Brésil (Paris: Hachette, 1862).

[19] “Ils sont bien drôles ces nègres de Rio, le pays où ils sont, je crois, le moins malheureux.” Biard, Deux années au Brésil, 89.

[20] “Quelles magnifiques vignettes abolitionnistes on ferait avec [s]es toiles.” Théophile Gautier, Abécédaire du Salon de 1861 (Paris: E. Dentu, 1861), 61–62.

[21] Klaus Berger and Diane Chalmers Johnson, “Art as Confrontation: The Black Man in the Work of Géricault,” Massachusetts Review 10, no. 2 (Spring 1969): 301–40, https://www.jstor.org/.

[22] Philippe Grunchec, Tout l’oeuvre peint de Géricault (Paris: Flammarion, 1978), 112–13 (where the work is identified as Portrait de nègre by Géricault, in a private collection in Paris); La Famille des portraits, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée des Arts Décoratifs, 1979), 92 (where the work is dated ca. 1818–19); Gisela Hopp, “Géricault: ‘Wirklich ist nur das Leiden,’” in Goya: Das Zeitalter der Revolutionen 1789–1830, exh. cat. (Munich: Hamburger Kunsthalle, 1980), 507 (where the work is placed within Géricault’s oeuvre as related to his studies for the Raft of the Medusa and to his contact with Alexandre Corréard, a survivor of the shipwreck of the Medusa and a strong advocate for the abolition of captive peoples’ markets in Africa); Werner Hofmann, “Kurzbiographien der Künstler und Verzeichnis ihrer ausgestellten Werke,” in Goya: Das Zeitalter der Revolutionen 1789–1830, 534; Germain Bazin, Théodore Géricault, étude critique, documents et catalogue raisonné, vol. 5 (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 1992), 119, 310 (where the work is titled “Nègre vu en buste” by “auteur inconnu,” in a private collection); and Jean-Pierre Changeux, La Lumière au siècle des lumières et aujourd’hui: Art et science, exh. cat. (Paris: Odile Jacob, 2005), 39, 345 (where the work is identified as an unfinished work by Géricault and dated ca. 1819).

[23] Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, La Famille des portraits, October 25, 1979 to February 15, 1980 (where the work is identified as Portrait d’un noir by Géricault, lent by a private collection); Hamburger Kunsthalle, Goya: Das Zeitalter der Revolutionen, 1789–1830, October 17, 1980 to January 4, 1981 (where the work is identified as Kopf eines Negers by Géricault, lent by a private collection in Paris); and Galerie Poirel, Nancy, La Lumière au siècle des lumières et aujourd’hui: Art et science, September 16 to December 16, 2005 (where the work is identified as Portrait de Nègre by Géricault, lent by a private collection in Saint-Mandé).

[24] The auction was held on November 8, 2017. See Tableaux, mobilier et objets d’art, auction cat. (Paris: Hôtel Drouot; Tessier & Sarrou et Associés, 2017), n.p., lot 12 (where the work is titled “Portrait d’homme noir” and attributed to Géricault).

[25] Lorenz Eitner, “The Literature of Art,” The Burlington Magazine 122 (March 1980): 209.

[26] See, for example, Edward Finden, after John Simpson, The Enslaved Man, 1827, engraving on cream wove paper, tipped onto brown wove paper, Art Institute of Chicago.

[27] Susan Waller, “Salem, the Prince of Tombouctou: A North African Model in Nineteenth-Century Paris,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 21, no. 3 (Autumn 2022), https://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/.