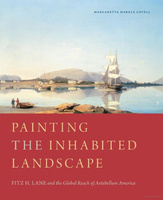

Painting the Inhabited Landscape: Fitz H. Lane and the Global Reach of Antebellum America by Margaretta M. Lovell

Reviewed by Kim OrcuttKim Orcutt

Independent scholar

Email the author: kimorcutt301[at]gmail.com

Citation: Kim Orcutt, book review of Painting the Inhabited Landscape: Fitz H. Lane and the Global Reach of Antebellum America by Margaretta M. Lovell, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 2 (Autumn 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.2.11.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Margaretta M. Lovell,

Painting the Inhabited Landscape: Fitz H. Lane and the Global Reach of Antebellum America.

University Park: Penn State University Press, 2023.

352 pp.; 84 color and 80 b&w illus.; bibliography; notes; index; appendices.

$94.95 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978–0–271–09278–2

This fascinating volume offers a truly fresh, original take on a well-known subject. Margaretta Lovell’s Painting the Inhabited Landscape not only provides a new perspective on the work of Fitz Henry Lane (1804–65), but also offers larger lessons for scholars who read it. To start, this is a beautiful volume, pleasingly designed and luxuriously illustrated. In an era of increasing online reading, it reminds us of the aesthetic pleasures of the book as object. It is also a pleasurable intellectual experience, substantial but straightforward. It is always interesting to read what can be considered a “magisterial” work from a seasoned scholar who puts the reader at ease with their confidence and insight, built on decades of accumulated knowledge.

The study is clearly laid out and the chapters are easy to follow. Lovell’s prismatic, somewhat non-linear structure results in frequent cross-referencing of images and doubling back. However, that complexity probably gets closer to the reality of multiple influences on Lane’s work than does a clean and potentially reductive narrative or totalizing explanation. The author’s kaleidoscopic approach is based on chapters that address selected aspects of Lane’s life and work to show that his paintings are not about stillness, but rather are about movement. She proposes that they are “not empty canvases full of silence but busy seascapes, landscapes, and townscapes full of purposeful activity. . . . They are about points of intersection between globally understood social and ecological systems” (17). For an artist whose career spans little more than twenty years and whose work (as the author shows) resists attempts to impose a trajectory of stylistic development, Lovell moves between the chronological and the thematic. The first three chapters introduce what can be known of Lane’s life, reputation, and early career, and the following chapters examine aspects of his work thematically, drawing on remarkably in-depth research to illuminate previously neglected elements of his work that offer a new understanding of the artist.

Lovell introduces her ambitious project to recast our ideas about Lane along the lines of canon formation and the intersection of the local and the global in the pre-Civil War period. She seeks to revise modernist binaries of large/small, grand opera/still small voice, and national/spiritual that have defined landscape paintings of the period, and to introduce nuance without losing sight of the distinctions that provide definition. Her research on the artist’s hometown of Gloucester, Massachusetts offers a vivid sense of the world that informed his works, and she explains the state of the Lane archive and the dearth of personal records that necessitate her emphasis on cultural anthropology via deep contextualizing, a methodology that downplays formalist readings and the role of individual “genius” that defined foundational writings on Lane. Similarly, the binaries of individual/culture and formal/contextual have sometimes functioned as poles on a methodological continuum for art historians in the past, but they don’t have to. While one approach can be overemphasized to the neglect of other perspectives, in Lane’s case, existing scholarship already provided formalist and individualist readings of his work so that Lovell’s book provides a balancing perspective.

Lovell clearly defines the parameters of her project: as a revisionist study, she focuses on single works and groups of works to shed light on the ways that Lane’s practice reflected his time and to provide a new understanding of not only the artist, but also of the nature of canon formation. She nonetheless covers a great deal of Lane’s career and many of the themes of his paintings and works on paper. Chapter 1, “Reputation,” concentrates on self-fashioning; that is, how Lane presented and promoted himself and his work. Lovell positions Lane as a “public artist” who played an active role in Gloucester, painting signs for businesses (such as fig. 1) and banners for public events, and whose works were often seen and promoted by local organizations. She addresses his sales strategies, including a surprising number of commissions, working with dealers, and through auctions and even a raffle. A cache of preparatory drawings offers clues that aid in understanding his preparatory process and his relations with patrons, as well as in pondering unlocated paintings. She also fleshes out early works such as book illustrations and ship portraits. The results of Lane’s efforts are demonstrated in contemporary responses to his works that coalesce around their accuracy, their efficacy in evoking memories and associations, and to a lesser extent, their poetic feeling.

Chapter 2, “Value,” addresses cultural fashioning—that is, the fall and rise of Lane’s posthumous reputation. Lovell explains that the artist was largely forgotten immediately after his death and traces his revival in the early to mid-twentieth century. She examines how Lane’s work was interpreted with a strong emphasis on formalism that culminated in his being identified with “luminism,” an invented movement that addressed the need for a triumphalist narrative of US art that ultimately served to legitimize the ascendant abstract expressionist movement. Lovell clearly and gently illuminates the drives behind canon building in previous decades. She builds a compelling case for an entirely new view of Lane’s work that upends received wisdom. For instance, she employs impressive research and incisive analysis to question the long-held (and naggingly convenient, I always thought) link between Lane’s work and Emerson and transcendentalism. Stripping away these layers of traditional understanding guided by scholarly agendas (however well meaning) allows the reader to see Lane’s work with fresh eyes.

The following chapters turn from chronological to thematic, discussing aspects of the antebellum United States as Lane presented them in his paintings. Chapter 3, “Canvas,” uses the material as a stand-in for discussing questions of identity. Lovell looks to contextual information about Gloucester to trace Lane’s evolving early identity, including an amusing and instructive account of the longstanding misidentification of the artist’s name as “Fitz Hugh” before it was finally corrected to “Fitz Henry” in 2004. Numerous quotations from the local newspaper suggest the issues and attitudes that shaped Lane’s world; the author successfully walks the fine line between providing context and making unwarranted connections. Lane’s evolution from shoemaker to lithographer to painter of the world that he saw and knew culminates with an examination of signatures and other coded allusions that would have been more legible in his time, thereby offering new insights on his work.

“Fish,” chapter 4, delves into Lane’s depictions of Gloucester’s economies of fishing and tourism. Lovell examines the artist’s renderings of different kinds of fishing—international, coastal, and recreational—pointing out how Lane distinguished himself from his contemporaries by painting extractive industries when other artists tended to suppress evidence of them or seek less domesticated scenes. Lovell observes that Lane depicts vignettes of activities that would have happened on a massive scale, for example, fish cleaning, and she describes the dangerous realities of the industry that would have informed the viewing experience of Lane’s fellow Gloucesterites. In another example of questioning received wisdom, Lovell argues persuasively that Lane’s pictures of wrecked boats on Brace’s Rock (fig. 2) were not allusions to the Civil War as previous scholarship posited, but more likely reference the actual wrecks that were a frequent and tragic part of local life. The rise of tourism in Gloucester and local leisure fishing gave rise to an “economy of looking” (135), creating new ways of valuing land for its views rather than its utility and landscapes that depicted scenery rather than human productivity.

Lane’s seemingly poetic Maine paintings of the 1850s and 60s often focus on aspects of the lumber industry and as with fishing, chapter 5, “Lumber,” demonstrates that the artist rendered specific vignettes rather than the large-scale activities that he would have observed. Lovell provides even-handed contextual information on the industry through the lens of its time and points out Lane’s respect for the important role that lumber played in building the world that he inhabited. Lovell also searches out indications of disharmony and imbalance in his selection of sites and within his paintings of Castine and Penobscot Bay, and small details are made to bear considerable conceptual weight. She identifies two very small figures in Castine, Maine (fig. 3) as Native American basket sellers and uses this as a point of departure for a lengthy discussion of the United States’ deplorable treatment of Native Americans in the antebellum era and the interactions of Lane’s ancestors with Native Americans, who killed several of his ancestors over the previous two centuries. It is also suggested that the cannons that Lane depicted in two paintings directly reference the town’s history of violence and military conquest that stretches back to the seventeenth century.

Granite is the subject of chapter 6. Lovell discusses the omnipresence of the rocks on Cape Ann and their commercial uses as seen in Lane’s treatment of them. Rather than painting rock portraits, the artist juxtaposed them with other materials, featured them prominently in landscapes, and occasionally made reference to the quarrying that played a significant role in the local economy. Lovell expands the discussion to the granite’s ultimate use in Bostonian monuments and architecture. She also studies Lane’s stone house in Gloucester. Employing a material rarely used in domestic architecture, he designed and built a home that shows his personal experience with the elemental material. Lovell suggests that his involvement with the heavy stone and the characteristically dark Gothic style of his house form another counter to the “luminist” characterization of his work as poetic and light-filled. The discussion of rocks segues to their role as catalyst for shipwrecks and a study of Lane’s lithographs and paintings of wrecks, which were more than a metaphor for Lane’s Gloucester viewers, but rather a reality that would have struck an emotional chord.

The final two chapters examine Lane’s patrons and how their travels, their global businesses, and their personal involvements gave Gloucester and Lane’s own paintings an unexpectedly cosmopolitan cast. In chapter 7, “Travelers I: Surinam and California,” Lovell again calls on the reader to look closely at the activity that they might have previously glossed over in Lane’s work. Paintings executed for George H. Rogers, an owner of Surinam-bound ships, lead to an interconnected web of associations with rum, the temperance movement that Lane supported, slavery, and abolitionism. Lovell suggests that Lane may have been an abolitionist as well, and the subject might explain the rift between the artist and his brother-in-law in 1862. If that was the case, it also raises the intriguing question of why the artist would take a commission from a man whose business depended on slavery. The California gold rush provides a backdrop for commissions that Lane received for works to be sent to the West Coast to preserve the memory of New England origins and ethos. The author uses vivid contemporary accounts to remind readers of how California gripped the public imagination as an “alternative utopia” where the prospect of striking it rich offered an escape from hard, steady labor. Lovell mines clues from preparatory drawings to suggest what the unlocated works might have looked like and makes a case for them as sermons on New England values.

Chapter 8, “Travelers II: Ireland, China, and Puerto Rico,” outlines Lane’s projects for two well-travelled patrons. His early work as a lithographer included an important commission for three ship portraits for Robert B. Forbes. Their dramatic backstories enliven our understanding of what now seem like innocuous, conventional images. Forbes’s involvement in the opium trade (then legal) is contextualized with remarkable research that includes the account of a seaman on one of the ships depicted, the Antelope (fig. 4). Lane’s commissions for Sidney Mason are illuminated by extraordinary documentation and posited as a set of “memory paintings” that hark back to important episodes from the patron’s life, and Lovell argues convincingly for additional Lane paintings as Mason commissions.

Lovell wisely notes that the meanings held by artworks can change over time, and she acknowledges that her interests in Lane’s global reach and the material world he inhabited are informed by the moment in which she is working. Her consciousness of how interpretive strategies change and are shaped by their time prompts us to ponder the biases and agendas (however unconscious) that shape our own approaches to US art history, and how we will be judged by future scholars. The author concludes that Lane is “an artist who speaks to us as he did to his contemporaries, but distance makes it a little harder for us to hear” (253–54). Painting the Inhabited Landscape offers new ways to hear Lane’s message and lets his works speak more fully and more eloquently, with their own voices. It provides an exemplary model for scholarship that invigorates and illuminates artworks on their own terms and those of their era. It uncovers the great richness of Lane’s work and transforms our experience of it. After reading this book I scanned through the Cape Ann Museum’s Lane catalogue raisonné, and it confirmed my conviction that I will not see his work in the same way again.