Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection

Reviewed by Laurinda S. DixonLaurinda S. Dixon

Professor Emerita

Syracuse University

Email the author: dixon01[at]twc.com

Citation: Laurinda S. Dixon, exhibition review of Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 2 (Autumn 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.2.17.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis

Part 1: May 14, 2022–March 26, 2023; Part 2: April 1–December 10, 2023

Catalogue:

Tom Rassieur, Winifred Smith, and Gabriel P. Weisberg,

Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection.

Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2022.

519 pp.; 189 color illus.; checklist; addendum; bibliography.

(hardcover) in a limited edition unavailable for purchase

ISBN: 978–0–9985872–4–0

(digital) available at no cost from the Minneapolis Institute of Art

ISBN: 978–0–9985872–3–3

Today, the real world is reproduced endlessly in photographs and films of actual people and places, and we take realistic depictions of daily life for granted. But this is a relatively recent phenomenon. In the nineteenth century, unidealized representations that sought simply to be true to nature could appear shocking, ugly, or offensive. The Minneapolis Institute of Art’s (Mia) exhibition Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection is an important reassessment of the realist and naturalist movements in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century art. It takes on the broad implications of these traditions within the varied contexts of daily life and culture. The exhibition also celebrates the shared lives of Gabriel and Yvonne Weisberg, who are recognized authorities in the realms of collecting, connoisseurship, and scholarship (fig. 1). Gabriel Weisberg has more than fifty-five books and catalogues to his name and worked throughout his career to broaden the canon of realist artists. The exhibition is a culmination of the couple’s tireless efforts to pave the way for a new understanding of realism as both an artistic style and a philosophical mindset. Indomitable art sleuths, the Weisbergs scoured galleries, bookstores, flea markets, and attics over a period of more than fifty years to discover works by lesser known and as-yet-undiscovered artists. Armed with impeccable credentials, engaging personalities, and scholarly knowledge, they rescued many a realist masterpiece from oblivion, including works by such able artists as François Bonvin (1817–87), Charles Milcendeau (1872–1919), Léon-Augustin Lhermitte (1844–1925), and Charles Jouas (1866–1942), among many others. These artists, though recognized in their time, are not household names today. Visitors to the exhibition will not find a single Gustave Courbet (1819–77) or Jean-François Millet (1814–75), the more canonical representatives of realism in art history. Nor will they find Vincent van Gogh (1853–90), who began his career as a realist, laying bare the tragic lives of coal miners in Nuenen (Netherlands) in The Potato Eaters (1885). Like Van Gogh, however, many of the artists in the Mia’s exhibition began as realists and assimilated other styles and approaches as their careers evolved. What unites them is the fact that too many have been ignored until now—some after becoming known in their lifetimes as proponents of realism in some form. The Weisbergs have brought them back to life and given their works renewed importance within the arc of history. As a result, there are some real discoveries in this show, and some important revelations as well.

So large is the Weisberg collection that the Mia wisely and generously presented it in two parts. The first ran from May 14, 2022 to March 26, 2023, and included works dating to the period from 1830 to 1900 (fig. 2); part 2, shown from April 1 to December 10, 2023, covered the years from 1900 to 1930 (fig. 3). Consisting mostly of French drawings, interspersed with a few well-chosen paintings, the exhibition’s more than thirty-nine artists and 189 works expand the definition of “realism.” Boundaries between artistic styles are fluid, and the works on display show traces of impressionism, symbolism, and art nouveau; together they explode any preconceived notion of realism as a style defined especially by Courbet. Meticulously finished drawings share space with preparatory sketches, and creative mixtures of media—chalk, gouache, ink, watercolor, charcoal, pencil—are often laid on tinted and textured paper. Multiple variations on the traditional themes of portraiture, landscape, and genre are contextualized by intelligent, substantive wall labels that provide windows into a complex and unstable period in European history. French politics from the July Monarchy (1830–48) through the Third Republic (1871–1940) were complex, contradictory, and mutable—swinging like a pendulum from republic to empire to anarchy and back again. Suffering, violence, and death were inescapable, as the era endured warfare, economic instability, class prejudice, and the relentless spread of incurable diseases such as tuberculosis, cholera, and syphilis. Simultaneously, the nineteenth century experienced unparalleled industrial advancement, wealth, and cultural excellence. The Mia’s show links these extremes, documenting the real world from farms to city streets, from kitchens to cabarets, from the glory of youth to the infirmities of old age.

Many of the works in part 1 demonstrate how artists boldly flouted the conventions imposed by the Academy, rejecting idealization, escapism, and exoticism in favor of gritty, truthful renderings of reality. They accentuated the inherent “crudeness” of their models by means of earthen colors, rough surfaces, and unapologetic exactitude, often obtained with the aid of the new medium of photography. The impact of the “real” world was felt across the cultural landscape of the era. In music, both bawdiness and pathos were celebrated in popular chansons and the verismo operas of Puccini (1858–1924). In literature the vivid, often brutal novels of Gustave Flaubert (1821–80) and Émile Zola (1840–1902) explored eroticism, violence, and the strictures of social conventions. The democratization of society, championed by many French critics and philosophers, coincided with Karl Marx’s (1818–83) Communist Manifesto (1848), which urged a proletarian uprising. It seemed that a world wounded by war, disease, and revolution sought healing in the recognition of the nobility, vulnerability, and pain of the human condition.

Demonstrating the power of art to express protest and achieve change in an evolving society is a major goal of the Mia’s exhibition, though it is part 1 that introduces Realism (with a capital “R”) as a distinct art movement. Though the new style was a shock to romantic sensibilities, it did not lack historical precedents. Many of the artists found inspiration in seventeenth-century Dutch art, which depicted more than ever before the bourgeoisie and coincided with the first capitalist democracy in the West. However, the quiet materiality of comfortable bourgeois life, evoked by Dutch painters such as Pieter de Hooch (1629–84) and Gerard Terborch (1617–81), excluded the poor peasant class in favor of monied merchants, who benefitted financially from bloody colonialism and capitalist financial ventures. Nonetheless, French realist artists selectively absorbed the lessons and spirit of the earlier era, which they saw as reflecting an ideal, egalitarian society. They applied those lessons to honest depictions of disadvantaged people, rendering them in subdued colors, subtle light effects, and structured compositions. These stylistic borrowings are evident in the appealing and masterful works of Bonvin (fig. 4), Jules Breton (1827–1906, fig. 5), Louis Welden Hawkins (1849–1910, fig. 6), and Milcendeau (fig. 7).

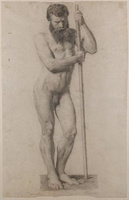

The realist school owed much to its seventeenth-century predecessors, but several works embody history and tradition in other ways. Lhermitte’s Standing Male Nude of 1864 (fig. 8), for example, may not immediately resonate with modern viewers, but it is in fact a sensitive restating of an ancient tradition. At a young age, Lhermitte moved to Paris, where he trained at the École impériale de dessin (Imperial School of Design), eventually achieving success and fame as an artist. His male nude draws upon a precedent that would have been familiar to him through his formal training, the Farnese Hercules (fig. 9), which was a standard academic reference in the nineteenth century. In the legendary work, Hercules the demi-God ponders the human frailty that determined his fate. In contrast, Lhermitte’s mortal man has a more ordinary physique and is exhausted by the burdens of life. Compared to the exaggerated musculature and elongated proportions of the antique Hercules, Lhermitte’s figure belongs unabashedly to the people, betraying his mortality in his stocky proportions, rugged, tanned forearms, and large feet. What better way to conjure the strength and nobility of a working man than by transmuting him into a modern god?

As realism emerged as a style, France was experiencing a period of immense prestige, when French cultural, educational, and technological innovations were studied and emulated everywhere. Leisure time was now attainable for members of the upwardly mobile middle class, who frequented fine restaurants like Maxim’s and the Moulin Rouge nightclub. Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s (1809–91) renovation of Paris bestowed the city with wide boulevards, green spaces, and sidewalks. The new Paris Metro allowed easy access to these neighborhoods, intermingling their populations in new ways. At the same time, there still existed a large underclass who never encountered these wonders and entertainments. The rural peasantry and Parisian slum dwellers experienced this era as a continuation of the struggles that had always marked their lives. Part 2 of the exhibition builds upon the stylistic innovations presented in part 1, enlarging the definition of realism to encompass a broader range of artists than is normally the case and focusing on the overarching themes of progress and social consciousness.

Jouas’s masterful pencil and chalk drawing The Mermaid of Hautefeuille Street (fig. 10) presents a less optimistic view of a historical remnant than does Lhermitte’s working-class Hercules. This powerful drawing is one of three similar works by Jouas that present the vanished glories of French medieval history, seen through a dark glass. The drawing depicts an architectural carving of a mermaid or siren dating from the thirteenth century. The figure originally served as an elaborate wooden buttress that once supported a monastic structure. By the time Jouas discovered it, the piece had been hidden in a cramped storage space and no longer served as an architectural ornament. The drawing, at once moving and disturbing, pictures the fierce and beautiful mermaid peering from her closet prison as if animated by some melancholy spirit. The detritus of old books and papers accompany her ignominious solitude. This work eloquently calls forth the relegation of France’s glorious past to the dustbin of history. Incredibly, the Weisbergs’ determined detective work tracked down the actual artifact, now restored and reincorporated into the architectural structure of the Hôtel des abbés de Fécamp in Paris.

Other works in part 2 demonstrate the absorption of realist elements by late-century artistic movements such as impressionism (fig. 11) and symbolism (fig. 12). An elegant example of the merging of painterly styles is Albert Maignan’s (1845–1908) October (fig. 13), a vivid landscape whose mournful effect is achieved by the contrast of earthen tones with vivid blue. The drawing’s dark mood is enhanced by the saturated colors of the pastels, which vividly evoke the distinctive light of dusk. Stylistically, the scene recalls the realist tradition, yet its rough handling and spiritual aspect link it to impressionism and symbolism. The scene depicts the single figure of a melancholy woman, dressed in black. She makes her way purposefully across the picture plane, symbolically approaching the end of her life, alluded to by the setting sun and the October landscape. The floral bouquet she carries recalls the fragility and brevity of youth, relinquished to the onslaught of time.

Several works directly relate to popular novels that eviscerated social mores, revealing corrupt and violent stories of human passion and crime. Art, literature, and music were closely intertwined in the nineteenth century, as is extensively documented in both the choice of pieces and the exhibition’s wall labels and catalogue. One example is a drawing rendered in crayon and watercolor by Louis-Maurice Boutet de Monvel (1850–1913, fig. 14) and created as an illustration for Ferdinand Fabre’s (1827–98) novel Xavière (1890). The scene of a young woman, collapsed in her sickroom and attended to by concerned family, was ubiquitous in French art and literature of the day. But the realist tradition, which did not shrink from brutality, explodes its normal meanings. Fabre’s story, set in rural Auvergne, tells of a widowed mother who plots to kill her daughter Xavière to gain the girl’s inheritance. Considered in this context, de Monvel’s subtle drawing is not a sweet expression of concern for the girl’s condition, but rather a representation of murder for money. The grim story also furnished the plot for an 1895 opera, also titled Xavière, by the composer Théodore Dubois (1837–1924).

Emile Claus’s (1849–1924) Ernestine (fig. 15), rendered in red chalk and wash, is another example of the merging of art and the written word. This is a virtuosic drawing in which the artist’s formal academic training and realist sympathies co-exist. The scrupulous linearity of the young woman’s face and hands, too fine to translate photographically, contrasts markedly with the sketchy treatment of her clothing. Her placid frontal pose and averted eyes mark her as a member of the humble class, a natural subject for realist artists. But in this case, as with de Monvel’s Xavière, the drawing’s title evokes deeper significance. It is doubtful that a nineteenth-century viewer would have assumed that Ernestine is simply the name of the young subject of the drawing. More likely, The Story of Ernestine, written by Marie Riccoboni (1713–92) in 1765 would have come to mind. The book was popular in the nineteenth century and recounts the story of an orphaned apprentice painter who becomes smitten by the handsome, aristocratic Marquis de Clemengis. As the heroine learns to negotiate questions of honor and reputation, she is confronted with the realities of class privilege and the precarious balance between financial security and the compromising nature of male generosity. The stylistic tension between the drawing’s meticulous line and sketchy finish echoes the clash between the ancien régime privilege and emerging egalitarianism.

Other works wrestle in different ways with questions of female expectations and capabilities. Georges d’Espagnat’s (1870–1950) crayon drawing Yvette Guilbert Singing (fig. 16) is one example. Guilbert (1865–1944) was a popular cabaret singer who headlined at the famous Moulin Rouge in Paris. Her stage act did not feature the indecent dancing and contortions practiced by other entertainers, such as Jane Avril (1868–1943) and Louise Weber (1866–1929), known as La Goulue. Guilbert’s appeal lay in the fact that she appeared onstage as seemingly virginal—pale, perilously thin, modestly dressed, and without rouge. However, the songs she sang, which described extreme states of passion, heartbreak, and abandonment, were far from chaste. Guilbert belonged to a large underclass of women, which included prostitutes, actresses, dancers, singers, and others who chose independence at any cost rather than submit to the constraints of marriage and motherhood. Their lives, lived outside the sphere of domestic respectability, predisposed them to a diagnosis of neurasthenia, a nervous disorder widely ascribed to women who challenged male authority. Guilbert resembles a typical neurasthenic in her sallow, green-tinged skin, listlessness, and thin, insubstantial body. D’Espagnat’s drawing contrasts with depictions of Guilbert by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901) and others, which show her as more buxom and animated. Like the stories of Xavière and Ernestine, this image of Guilbert draws attention to the limited choices and physical vulnerabilities of nineteenth-century women.

A pervasive theme in the exhibition is industrialization and mechanization, which affected the arts directly. Chemical colors enriched the craft of painting and viewers’ responses to it, and in the realm of music, the invention of new instruments enhanced the experience of listening and performing. The piano is the most familiar of these, but Antoine-Jean Bail’s (1830–1919) painting The Cornet (fig. 17) records the transformative improvements made in the construction of brass instruments in the nineteenth century. Bail’s cornet is carefully painted to show the addition of valves, which allowed brass instruments to produce every pitch along the harmonic spectrum. Before this time, these instruments were so difficult to play that they were the province of elite guilds and not heard outside of orchestras and court functions. The relative ease with which they could now be learned and played attracted an increased number of interested performers. The valved horn, though controversial, was ultimately greatly beneficial to both performers and audiences. However, the march of progress did not always yield such positive results. An example is the fatal blow dealt to “cottage” industries, small family businesses that became obsolete with the rise of industrialism. Lhermitte’s The Weaver (fig. 18) shows this phenomenon in a pessimistic light. The scene is the grimy interior of a weaver’s studio, where a man and woman, probably a husband and wife, labor over the making of cloth by manual spinning and weaving. Reinforcing the simplicity of their surroundings is their basic two-harness loom, capable of producing only a simple plain weave pattern. By the time of this drawing—1887—cloth was no longer made on individual looms operated by hand shuttles and foot pedals. The new looms were powered by steam and controlled by cards with punched holes. Luxurious mass-produced silks and damasks became available for sale on the mass market, but at the expense of “bedrock” family businesses, such as the one memorialized by Lhermitte.

Landscape is the vehicle for a great variety of stylistic approaches, from scrupulous linearity (fig. 19) to postimpressionist freedom (fig. 20). The theme of the natural world had both aesthetic and ecological relevance in the nineteenth century, as it does today. Visions of untrammeled nature reminded some viewers of the ecological threats of railroads and factories to formerly pristine lands. Some artists saw real beauty, however, in the new environments created by industrialism. Édouard-Louis Henry-Baudot’s (1871–1952) Deule Bridge, Douai (fig. 21), for example, dematerializes its industrial subject with diaphanous clouds of impressionistic vapor that contrast markedly with the stark reality of a typical nineteenth-century factory landscape.

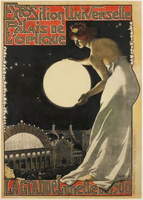

Many life-changing scientific and technological innovations were developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including the automobile, telegraph, electric light, telephone, cinematography, the germ theory of disease, and Freudian psychology. The bright optimism of the age is apparent in a remarkable pairing that testifies to the diligence of the Weisbergs in locating and identifying unique preliminary studies of larger, finished works. Several examples appear in the Mia exhibition, but Georges Paul Leroux’s (1877–1957) study for the poster Exposition Universelle—Palais de l’optique la grande lunette de 1900 (fig. 22) is a notable example. International expositions such as the one in 1900 served as vehicles for informing and entertaining the public about new marvels of art and technology. The Grande lunette was a giant telescope that allowed greatly magnified views of the moon, and perhaps inspired Georges Méliès’ 1902 film Le voyage dans la lune (Voyage to the Moon). The finished color lithograph poster (fig. 23), hung next to the preliminary charcoal study (fig. 22), features the lunar muse, whose feminine grace belongs to the fashionable style of art nouveau that swept the world at the turn of the century.

Reflections on Reality is more than a display of beautiful objects, though it is that, to be sure. Its expansive approach is enhanced by the accompanying catalogue, which is essential to a full appreciation of both parts of the exhibition. Its text and images are all available digitally, free of charge through the Mia’s permanent website, which offers zoomable images of all works. The book contains reproductions and entries for nearly every piece, biographical information on each artist, and thoughtful historical contextualization. Winifred Smith’s biographical essay begins the catalogue and relates the art historical adventures of the Weisbergs, the Holmes and Watson of art history, with admiration and warmth. Following it is Tom Rassieur’s concise scholarly essay introducing the collection, the philosophy that guides it, and its art-historical significance. For ease of reference, the catalogue’s 189 high-quality images and entries are arranged alphabetically according to artists’ names. Together, the exhibition and catalogue demonstrate the rare qualities of connoisseurship, substance, and intellectual rigor that define every corner of this thoughtful show. Its carefully chosen pieces comment on many rich and complex aspects of nineteenth-century art and offer an expansive exploration of a time that was, in fact, much like our own in its rapid change and disparities of wealth.