Myth and Meaning in Edward Burne-Jones’s The Flower Book

(1882–98)

by Megan McNally

Megan McNally holds a BA from Wellesley College in art history and French, and an MA in art history from the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. She is a former Soriano Fellow at the Musée du Louvre, and works at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston. This article is based on her master’s dissertation at the Courtauld Institute, supervised by Caroline Arscott.

Email the author: C2016281[at]courtauld.ac.uk

Citation: Megan McNally, “Myth and Meaning in Edward Burne-Jones’s The Flower Book (1882–98),” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 2 (Autumn 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.2.6.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

In 1882, sixteen years before his death, the Pre-Raphaelite British painter Edward Burne-Jones (1833–98) embarked upon The Flower Book (1882–98), a project which would occupy him for the rest of his life and which has largely been neglected in scholarship despite its close affinity with the artist’s other work. The Flower Book consists of thirty-eight watercolor roundels, each approximately 6 in. (16 cm) in diameter. It was posthumously published in 1905 by his wife, Georgiana, Lady Burne-Jones (1840–1920), who commissioned three hundred color facsimiles for the Fine Art Society, printed with remarkable quality by Henry Piazza (1861–1929).[1] Each image takes its title from a flower name, generally a common name unique to English rural use. To find these flower names, many of them obscure, Burne-Jones relied upon the horticultural knowledge of his friend and correspondent, Eleanor, Lady Leighton Warren (1841–1914).[2] It was requisite that each flower name provide a suitable point of origin for an image, although in most cases the image is not a literal visual correlate to the flower: as Burne-Jones wrote, “farfetched is best.”[3] In each instance, it is the name rather than the flower itself that is illustrated, the name serving as the point of departure for a miniature, which is most often inspired by a biblical, mythological, or literary source already represented by Burne-Jones earlier in his career but which in some cases is far more cryptic. Traveller’s Joy (fig. 1), for example, takes its name from a flowering vine, but the miniature represents the Three Kings arriving at the manger. As a result, The Flower Book consists of a disparate series of images that I argue are united by the study of myth, which John Ruskin (1819–1900) identified as a critical component of Burne-Jones’s artistic practice.[4]

In The Flower Book, Burne-Jones seems to apply methods from both biblical and mythological studies of his time period to his own form of mythmaking. Through this exercise, a unifying, although not entirely scrutable, meaning is created from the relationships between both the watercolors themselves and Burne-Jones’s earlier work. In this article, I first discuss the linguistic and visual processes of The Flower Book to demonstrate how Burne-Jones presents himself as a mythmaker. I then describe the ways in which Burne-Jones’s repetition of motifs serves to produce meaning, and how he may have employed a parable model from Christian scripture to obscure that meaning. These two narrative forms of myth and parable are similar but distinct: both are variations on metaphor, but in parable this metaphor is made deliberately difficult to decipher. Unlike myths, which develop over time and pass through a series of storytellers, the parables of the New Testament come from Christ alone. While myth provides the organizational structure of The Flower Book, the images position the relationship between Burne-Jones and his viewer as one of a parable’s speaker and listener. Like myth and parable, The Flower Book operates through a series of metaphors: for every title or image that is given, something else is intended. Taken together, the watercolors of The Flower Book may present a single, epic myth which engages the viewer in interpretation but whose significance is never fully elucidated. As in parable, this opacity is purposeful, drawing the viewer into an interpretative experience which has its own rewards.

The Flower Book has seen little serious investigation in Burne-Jones scholarship. Some of the best descriptions of the book can be found in Penelope Fitzgerald’s biography of Burne-Jones (which I will further discuss later) from 1975. Fitzgerald, like Lady Burne-Jones (whose Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones gives a detailed account of her husband’s life and career), characterized the watercolors as a relaxing side project, but noted that Georgiana Burne-Jones failed to capture “quite how odd the ‘soothing work’ was.”[5] As Fitzgerald suggests, there is indeed something amiss—or rather, some mystery—in The Flower Book which deserves further consideration. That same year, the Arts Council of Great Britain placed The Flower Book in the “Minor Works” section of the catalogue for its exhibition of Edward Burne-Jones, remarking primarily upon the repetition of motifs from Burne-Jones’s previous work.[6] In Edward Burne-Jones: Victorian Artist-Dreamer, Stephen Wildman and John Christian thoughtfully describe the blend of new subjects and recycled themes as well as the influence of Rottingdean, Sussex, where Burne-Jones had a home, in the pastoral landscapes in many of the watercolors.[7] Fitzgerald also saw Burne-Jones’s life spilling over into the images, noting that the young woman in Welcome to the House (fig. 2), resembles his daughter Margaret (1866–1953), although most of the figures in The Flower Book have indistinct features.[8] While it is surely true that the artist’s life and surroundings play a role in the images, and in some cases provide a layer of meaning behind the metaphors, a primarily biographical approach fails to capture the total project of The Flower Book. Although it is widely accepted that Burne-Jones repeated themes of personal significance to him from one work to another, the question still remains as to why he chose to place these particular images together in The Flower Book, united by a common method and style. Beyond each watercolor’s potential connection to his own life, they hold connections to one another. In this article, I seek to address this question, first by looking at mythographic sources from Burne-Jones’s own era, primarily the work of Max Müller (1823–1900), to consider how Burne-Jones may have understood the operation of myth. I then apply strategies from structuralist theory to analyze the relationships between The Flower Book images, and I discuss how hermeneutics may be applied towards their interpretation. By examining The Flower Book through this broad lens, I explore not only its role in Burne-Jones’s life but also the role he may have intended it to play as an independent work of art.

What It Means to Make a Myth

Let us begin by taking a closer look at Burne-Jones as a mythmaker, starting with the watercolor Love in a Mist (fig. 3). Probably the first image Burne-Jones completed for The Flower Book, it likewise appears on the book’s first page.[9] It depicts “a mist which does not rise from the earth but is made of heaven’s blue” and enmeshes “Love himself, baffled and blinded by its folds.”[10] Except for its color, the image holds nothing in common with the flower from which it takes its name, a species of blue buttercup (fig. 4). In the illustration, a red-winged Cupid shields his eyes with his arms and hands as he gazes through a swirling blue mist. There is a transference of signification: the name love-in-a-mist, which perhaps originally referred to the color of the flower or the “misty” mass of wispy leaves surrounding it, now means something else entirely: the personification of love in an actual mist.

The metamorphosis which took place in the creation of this image may have its roots in mythography. Burne-Jones’s mythmaking developed during a period in the late nineteenth century when early anthropologists were investigating myths to understand not only their meanings but also their origins. Collectors of folklore such as Andrew Lang (1844–1912) became increasingly aware that stories from around the globe shared notably similar characteristics. Opinions about why this was so and how myths were first formed differed. The mythologizing process of The Flower Book holds most in common with the theory posited by Müller, a philologist of the previous generation. Müller was among the first to consider the origins of myths, in ideas widely disseminated in the late 1850s and 1860s. He traced many myths to the sun or the dawn, as he believed these “intangibles” represented the infinite and the divine in ancient civilizations.[11] Furthermore, he thought that the formation of early languages could explain the existence of mythological stories. According to Müller, myths were invented by early humans to explain archaic expressions and linguistic inconsistencies—what he called a “disease of language.”[12] Simply put, Müller believed that stories were invented for metaphorical expressions whose original meaning had been lost.[13] He wrote: “Whenever any word that was at first used metaphorically is used without a clear sense of the steps that led from its original to its metaphorical meaning, there is danger of mythology; whenever these steps are forgotten and artificial steps put in their place, we have diseased language, whether that language refers to religious or secular interests.”[14]

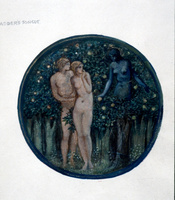

In theory this could happen in a number of ways. For example, Müller theorized that early people may have believed that synonyms came into existence because two or more gods had powers associated with a particular object; the object might be referred to by a name related to either god.[15] In other cases, what Müller regarded as the limitations of early language might create expressions that grow into myths. He suggested that stories of the dawn dying before the sun rises were a means of saying “the sun has risen—the dawn is gone” in a primitive language that lacked sufficient vocabulary to describe the phenomenon.[16] However, he emphasized that once this initial transformation occurs, the myth takes on a life of its own. He explained, “It is the essential character of a true myth that it should no longer be intelligible by a reference to the spoken language.”[17] The same is often true of the relationship between the flower names and Burne-Jones’s images. Adder’s Tongue (fig. 5), for example, shows Adam and Eve before the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. In the biblical book of Genesis, a snake offers Eve a taste of the tree’s fruit, although God has forbidden her to taste it. In the variation in The Flower Book, the figure of the snake has been further metaphorized, drawn instead as a blue-fleshed woman who rises from the trunk of the tree itself—and who bears a marked resemblance to Eve. Given the two parts, name and image, it is easy enough to see how they fit—the adder is a type of snake, and it is the words from the tongue of a snake, so to speak, that first draw Eve to temptation—and it is with her own tongue that she first tastes that temptation. However, looking at the image alone, the words “adder’s tongue” do not immediately spring to mind.

Considering that Müller lectured on mythography at Oxford while Burne-Jones was a student there, and that his ideas influenced Burne-Jones’s mentor Ruskin, it seems highly probable that Burne-Jones was at least familiar with the bones of Müller’s theory on language.[18] Müller’s enduring influence can be felt as late as 1891 on John Rhys’s (1840–1915) Studies in the Arthurian Legend. Burne-Jones, a prolific and scholarly reader, confessed himself disappointed and frustrated by this text on his favorite subject, which borrowed heavily from Müller and devoted much of its space to tracing the Welsh linguistic origins of various personages in Camelot.[19] In a letter to Lady Leighton Warren, Burne-Jones called it “a pedantic book full of hazardous doubtful conjectures of etymology & sickening stuff about culture heroes & sungods & little hints about things one is dying to know about.”[20]

While Burne-Jones clearly took issue with this extensive application of Müller’s theory, he himself may have been more under its influence than he cared to admit. Andrea Wolk Rager has compared his practice as an artist to the mythographic endeavors of Müller and Lang.[21] Likewise, Fortunée de Lisle (1866–1910) noticed something akin to a linguistic process in Burne-Jones’s artistic practice, describing his gift of bringing myths to life so as “to make them speak our own language.”[22] However, as Wolk Rager has noted, Burne-Jones’s relation to his sources is not one of “direct translation.”[23] Rather, The Flower Book presents a mythmaking act of transmutation.

Just as the connection between the original metaphor and the resulting myth is severed in Müller’s mythography, so there is no association between the flowers whose names Burne-Jones appropriated and his illustrations: as Georgiana Burne-Jones remarked, “not a single flower itself appears.”[24] Like Ruskin, who warned in Proserpina that “etymology, the best of servants, is an unreasonable master,” Burne-Jones was interested in etymology as not an end unto itself but rather as a tool in the service of mythmaking.[25] By imposing an image—and therefore a meaning—upon archaic flower names, Burne-Jones made himself the sole bearer of their truth. Georgiana Burne-Jones wrote that he rejected any flower names with “too obvious a meaning, as for instance Odin’s Helm or Fair Maid of France . . . because there was not any reserve of thought in them for imagination to work upon.”[26] Her statement suggests that Burne-Jones was deliberately seeking a potential point of rupture in which to be the mythmaker. Burne-Jones himself spoke of “making” the subjects of his pictures rather than finding them in a mythic source: “I make them—or at least, I entirely re-make them from vague impressions left by poems I have forgotten.”[27] As in Müller’s theory, a phrase whose meaning has been obscured by time could be reborn as something new.

We can return to Love in a Mist to further examine how Müller’s theory plays out in Burne-Jones’s mythmaking. As with “diseases of language,” Love in a Mist represents a loss of metaphor vis-à-vis the original reason for the flower’s name. In Müller’s example of the sun and dawn, the story of the personage of dawn physically dying before the sun takes literally the phrase “the dawn dies before the sun,” while the phrase originally was a metaphor for the sunrise. Likewise, the “mist” in the plant known as love-in-a-mist is a metaphor for the plant’s wispy leaves, while in Burne-Jones’s representation it is the literal weather phenomenon. As with Adder’s Tongue, the image of a winged man caught in a cloud of mist does not immediately strike the viewer as being equivalent to the phrase “love in a mist.”

However, while Müller’s mythography offers an operational structure for the individual watercolor roundels, there remains the question of their relation to one another. The god of love was surely a significant personage for Burne-Jones, who illustrated the tale of Cupid and Psyche several times, including in a frieze for a private residence at No. 1 Palace Green in London (fig. 6) and in a series of drawings for wood engravings for his friend William Morris’s (1834–96) poem “The Story of Cupid and Psyche.” The drawings for the poem, made circa 1864, are in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford; wood engravings after Burne-Jones’s illustrations are at the British Museum in London (fig. 7), among other locations.[28] In the tale, it is Cupid’s human lover, Psyche, who is lost and whose vision is obscured. She is only permitted to meet Cupid in the darkness, but she breaks this interdiction by lighting a candle. Cupid flees her, and she must go on a quest to find him and restore their love. Does Love in a Mist represent a moment of untethered emotion in Burne-Jones’s own life? Or, as will be discussed below, should it be considered in a less biographical manner in relation to the other lost or seeking figures, such as the Three Kings, who are featured in The Flower Book? In other words, does mythmaking occur not only within the individual images but also between them?

There is an obvious problem in the conception of Burne-Jones as mythmaker, because many of the myths treated in The Flower Book already existed at the time its images were made. The work of the Soviet folklorist Vladimir Propp (1895–1970) is of some use here. Propp regarded myth and fairy tale as historically and structurally one and the same, a perspective that well suits The Flower Book, in which there is no distinction between how Greco-Roman and medieval sources are treated.[29] He noted that storytellers rarely invent new tales but instead alter or combine existing ones. There are some general rules for how this happens in practice. For example, storytellers should not alter the sequence of events, but they may choose what elements or events are included and what form they take. Above all, “the storyteller is completely free in his choice of the nomenclature and attributes of the dramatis personae [and] in his choice of linguistic means.”[30] Georgiana Burne-Jones remembered her husband as possessing a talent for spinning tales in this style: “He would find the dry bones of some ancient story buried in scholarly notes, and make them live again, in a form of his own devising, neither old nor new, but strangely romantic.”[31] In this sense, Burne-Jones is a mythmaker because he assumes linguistic authority, regardless of the previous state of existence of the myth he adopts. If we substitute the phrase “linguistic means” for “visual means,” he is further a mythmaker on account of his choices of representation.

Repetition and the Making of Meaning

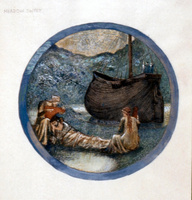

Perhaps the most striking aspect of The Flower Book is how many images are derivative of Burne-Jones’s earlier work. Burne-Jones frequently recycled themes throughout his career, and in The Flower Book many of the stories he favored from mythic and literary sources appear once again. Examples include Meadow Sweet (fig. 8), which depicts the same episode from Arthurian legend as The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon of 1881–98 (fig. 9), and With the Wind (fig. 10), an illustration of Dante’s Paolo and Francesca, which is one of several Flower Book entries to have a sister image in Burne-Jones’s The Secret Book of Designs of 1885–98 (fig. 11). Several stories and individuals also appear multiple times: Venus three times, for example, and the Annunciation twice. Concurrently, many of the images deal with themes of rebirth. This repetition and “resurrection” of subjects in The Flower Book allows for the making of meaning from myth.

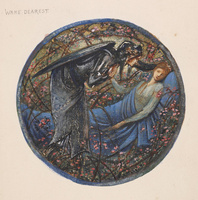

Among the mythical sources obviously related to Burne-Jones’s earlier work is the tale of Briar Rose (also referred to as Sleeping Beauty), portrayed in Wake Dearest (fig. 12). In this image, a knight clad in the silvery gray, shiny armor characteristic of Burne-Jones’s style leans over the sleeping princess and presses her hand to his heart, the two figures enclosed in a swirl of rosebuds. Briar Rose was a story of particular significance to Burne-Jones, who first depicted the theme in 1864 in a set of Morris & Company painted tiles for the home of Miles Birket Foster (1825–99). Sleeping Beauty was also a recurrent subject in the work of Burne-Jones’s contemporary Walter Crane (1845–1915), who, influenced by Müller, harnessed the story for a socialist allegory.[32] Burne-Jones continued to rework the motif, culminating in a series of paintings completed in 1890, now at Buscot Park in Oxfordshire (fig. 13, The Rose Bower, is from this series).[33] There is a good chance that Wake Dearest was painted sometime during or around the time of this project. What started as merely a source of inspiration may have burgeoned into something more personal, as the Buscot Park paintings are widely viewed as a metaphor for the marriage of Burne-Jones’s daughter Margaret in 1890.[34] For her wedding gift in 1888, Burne-Jones painted yet another Sleeping Beauty, this one in gouache (private collection).[35]

Burne-Jones repeated the representation of a sleeping figure in Flame Heath (fig. 14). Brynhilde, a figure from the Norse and Icelandic tradition, is, like Briar Rose, awakened from her sleep by a warrior, in this case the hero Sigurd.[36] Burne-Jones also illustrated Brynhilde for the 1898 Kelmscott Press edition of Morris’s poem The Story of Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of the Niblungs.[37] In Flame Heath Brynhilde lies asleep along a blue hillside, golden flames punctuating the length of the ridge like waves upon the sea. The similarity between the two sleepers’ poses suggests that Burne-Jones intended the viewer to make a connection. Wake Dearest is among the more colorful of The Flower Book images, with the princess wrapped in a bright blue cloth and surrounded by pink rosebuds whose branches curve along the length of her reclining form. Certainly, this image serves as an antidote to the numerous representations of heroes on a quest for a highly sought object or individual in other pictures of The Flower Book, from Theseus to the Three Kings; here, what was desired has been found. The horticultural element is also pertinent: Caroline Arscott describes the dual wounding of knights who attempt to fight through the briars enclosing the palace and of the princess on the spindle in the Briar Rose narrative as a kind of horticultural grafting.[38] Like two plants which have been cut and joined together, the successful knight and the princess both face injury from the briars and the spindle. In their union, new life and regeneration occurs.

In Flame Heath and Wake Dearest repetition operates on multiple levels. First, not only does each watercolor reference its sister image within The Flower Book, but it also recycles and makes reference to significant motifs from Burne-Jones’s earlier work. Each narrative also deals with resurrection, as both Brynhilde and Briar Rose wake from a deep sleep as if coming back to life. In Wake Dearest, the horticultural theme furthers this concept of rebirth through the cycle of injury and regrowth, loss and return in the natural world. In this way the image has much in common with Key of Spring (fig. 15), which shows an angel in vibrant blue against a desolate winter landscape, holding a key in her hand and “unlocking a tree that the sap may rise.”[39] As sleepers wake, so does the spring, and it does so again and again in the cycle of the seasons. The many and varied forms that the concepts of repetition and rebirth take in The Flower Book suggest that they are key to understanding the work.

Of all of the repeating narratives in The Flower Book, White Garden (fig. 16) and Flower of God (fig. 17) are among the most intriguing. Unlike in other images where two different points in the narrative are depicted—the sighting of the star in Star of Bethlehem (fig. 18) and the arrival at the manger in Traveller’s Joy (see fig. 1), for example—here the same moment in the Annunciation is pictured twice. In both images, the Virgin Mary encounters the angel Gabriel. The two white-robed figures are set against a dense visual field abundant with vegetation (lilies in the White Garden; wheat in Flower of God) which ascends vertically, leaving no room for sky. In White Garden, Mary bows before the outstretched wing of Gabriel, while in Flower of God she accepts a lily from the angel. The plant motifs in both images further regenerative themes: wheat suggests the abundance of the harvest, while the lily is the flower of Easter and Christ’s resurrection. However, the focus in both images is not on the plants themselves but on the divine miracle they represent.

Burne-Jones had painted the Annunciation many times before, including a commission in gouache for the Dalziel Brothers in the early 1860s titled The Annunciation—“The Flower of God” (private collection).[40] The version of the subject in Flower of God is perhaps most similar to the mosaic The Annunciation which Burne-Jones designed for the American Episcopal Church in Rome in 1890 (fig. 19 shows a preliminary sketch for the mosaic).[41] Both share a certain starkness and the image of an angel with magnificently long, sweeping, teardrop-shaped wings. The compositions of White Garden and Flower of God are highly simplified, and each work has a dominant and striking color theme, either white or gold. While both colors might signify the Virgin’s purity, their purpose may also be to simplify the visual elements in each image, heightening the focus on the central action. This distillation contributes to the sensation of the mystery and intensity of the encounter, giving a strange power to The Flower Book Annunciations.

In her husband’s biography, Georgiana Burne-Jones quoted from The Poetry of Christian Art (1854) by Alexis-François Rio (1797–1874) to explain the preponderance of certain themes in her husband’s work: “The progress of an artist who seeks his inspiration beyond the sphere of sensible objects . . . [consists] in the development and progressive perfection of certain types, which, concealed at first within the most secret recesses of his imagination, . . . had at length become intimately combined with all that was poetical and exalted in his nature.”[42] Burne-Jones, she suggested, resurrected images in order to refine them.

Moreover, it is no accident that so many of the “resurrected” themes were ones that Burne-Jones considered as signifiers of moments in his own life. Besides Briar Rose, there is also Witche’s Tree (fig. 20), a variation on his The Beguiling of Merlin of 1870–74 (fig. 21), alluding to his doomed affair with the artist and model Maria Zambaco (1843–1914).[43] In Witche’s Tree, the enchantress Nimue stands with her back to the viewer, working a spell on Merlin, who under her power falls asleep among the densely winding, white-flowered branches of a tree. This tree is markedly similar to the one in which the wizard sleeps in The Beguiling of Merlin, although in the larger painting Nimue’s position is reversed. Parallel tales were a popular subject in both Victorian mythography and theology, as was the concept of typology, in which events, rituals, or personages of the Old Testament prefigure the resurrection of Christ. Unlike myths, types were considered to be grounded in historical reality.[44] However, in The Flower Book the typological and the mythic are not necessarily at odds. A central aspect of typology is the idea that “scriptural types could be fulfilled in the individual’s own life.”[45] If the images of The Flower Book are instead mythic types for Burne-Jones’s own experience, this would better contextualize their repetition. However, this is not to say that their significance can be reduced to the mere biographical. George Landow wrote that “the type allows one immediate access to the meaning of the universe.”[46] In a similar way, Fitzgerald described Burne-Jones’s process in The Flower Book: “If the name was right, it opened a direct access, like an intensified view through a small round window, into the world where his own limited range of private images joins the world’s store of archetypes.”[47] The repeating narratives of The Flower Book are perhaps best considered as a form of access to a new plane of meaning that transcends both the individual and the archetypal.

Like numerous other mythographers, Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009) understood myth as structurally akin to language or even a form of language. He noted that just as with language, meaning in myth comes from “the combination of sounds, not the sounds themselves.”[48] In Myth and Meaning, he further elucidated this point, writing that “the basic meaning of the myth is not conveyed by the sequence of events but—if I may say so—by bundles of events even although these events appear at different moments in the story.” To understand the myth, then, one must take instances of the same theme in the story, “pile them up one over the other, and to try to discover if they cannot be treated as one and the same event.”[49]

This tactic might be applied to The Flower Book as a whole, whose organization in both the original version and in Piazza’s 1905 facsimile defies a sequential reading (in the latter, the watercolors are individually numbered, but not entirely in the chronological order of their creation). Instead, the book might be understood in the grouping of like images, even if they depict different narratives. In this respect The Flower Book is perhaps not a collection of myths but a single epic myth. Could the striking visual similarities of Golden Cup (fig. 22) and Star of Bethlehem (see fig. 18), for example, suggest an equivalence between the quest for the Holy Grail and the Three Kings’ quest for the Christ child? What happens when the Annunciation, the waking of Briar Rose and Brynhilde, and the first day of spring are “treated as one and the same event”?

Certainly, the epic myth was a narrative form that was intimately familiar to Burne-Jones. Morris, his close friend and collaborator, was a writer and scholar of epic poems. As Florence Boos has documented, Morris’s poetry, beginning with The Earthly Paradise, is often characterized by both allegory and “extensive mythopoetic use of folk and saga material.”[50] There are also “epics” within Burne-Jones’s own work, when a myth is narrated by a series of images, such as the Cupid and Psyche murals for No. 1 Palace Green and the ten gouache studies of the Perseus series (1876–88; Southampton City Art Gallery, Southampton). Perhaps The Flower Book follows this same model, fashioning the epic not from one myth but from many. Stylistically, Burne-Jones was skilled at taking examples from across the canon of Western art and synthesizing them into cohesive works of art.[51] Elizabeth Prettejohn writes that he was “interested not merely in imitating specific artists but rather in revealing, or proposing, affinities and correspondences among them . . . [and he was] adept at combining sources of inspiration so as to create new meaning as well as new form.”[52] It seems likely that he would apply this approach to his own oeuvre, creating new meaning from the combination of disparate narratives.

Just as the miniaturized, simplified compositions of The Flower Book lose the detail of large-scale series like Briar Rose, mythic tales reduced to a single epic in this way lose their individuality. What the images of The Flower Book gain from this distillation is the promise of renewal—that a story once started will find life again in a different guise. The meaning behind the images may be that as long as Burne-Jones’s own story can continue to be retold, it is not yet over. As Lévi-Strauss wrote, “what gives the myth an operational value is that the specific pattern described is timeless; it explains the present and the past as well as the future.”[53] Toward the end of his life, Burne-Jones mythologized his own past, finding meaning in the cyclical, whether that was the ebb and flow of his personal history, the reawakening of a princess, or a Christian story.

Parable and Meaning Made Mystery

In June of 1886, Burne-Jones wrote to his friend Lady Leighton Warren with a long list of flower names he intended to illustrate in The Flower Book. He told her, “You see how I want to deal with them—making them all a little mysterious & sibylline & Delphic & as if the secret they hold was very precious.”[54] Later, Georgiana Burne-Jones would write of her husband, “He was often amused by the anxiety people had to be told what they ought to think about his pictures as well as by their determination to find a deep meaning in every line he drew.”[55] While meaning might be ascertained from The Flower Book, the lack of detail and clarity in both the images and their floral titles do not make this an easy task. Burne-Jones deliberately obscured meaning in The Flower Book, perhaps taking scriptural parable as a literary model for its content.

As he was beginning to paint the first watercolors for The Flower Book in the autumn of 1882, Burne-Jones told Leighton-Warren, “But lovely and fanciful as the names are . . . I find how few really are capable of any artful treatment: & I wish not to do any commonplace thing in this world if I can help it, lest the people should understand and be converted & saved.” At the bottom of the page he scrawled two biblical citations, the first of which reads “Ephesian xi 53,” or possibly “Ephesian ii 53,” and the second of which reads “see also Corinthians, III xxv 2–6.”[56] These are immediately puzzling: there is no fifty-third verse in any chapter of Ephesians (nor does Ephesians 6:5–3 apply contextually); nor is there a third letter to the Corinthians. Two possibilities present themselves. The first is that Burne-Jones, who wrote letters prolifically and oftentimes hastily, put down the citations from memory without consulting a Bible and got them wrong. This seems unlikely: Burne-Jones, who had originally planned to join the ministry, would at the very least have known that there is no Third Corinthians. Most likely, these nonsensical references to Bible verses are a joke: by giving a citation which is impossible to understand, he ensures that the reader cannot “understand and be converted & saved.”

Even if the two citations are imaginary, the language Burne-Jones employs to describe his project is reminiscent of several very real passages in the Bible. For example, there is Isaiah 6:10 (“Make the mind of this people dull,/ and stop their ears,/ and shut their eyes/ so that they may not look with their eyes,/ and listen with their ears,/ and comprehend with their minds,/ and turn and be healed”) and Matthew 13:15 (“For this people’s heart has grown dull, and their ears are hard of hearing,/ and they have shut their eyes;/ so that they might not look with/ their eyes,/ and listen with their ears,/ and understand with their heart and/ turn—/ and I would heal them”).[57] It also brings to mind the parable of the sower in the Gospel of Mark, which makes reference to Isaiah and is, somewhat infamously, among the most inscrutable of Christ’s parables. Like Burne-Jones’s watercolors, the parable of the sower uses horticultural metaphor to communicate its message and can perhaps be employed as a model for the mysteries of The Flower Book.

In How to Do Things with Fictions, the scholar of comparative literature Joshua Landy takes on the question of parables in the Gospel of Mark. Although the parables are often taken as explanations of the Christian faith, Landy writes that the opposite is, in fact, often true, and that there is a “deliberate opacity”: “Far from taking something complicated and making it clearer, the parables take something transparent and render it incomprehensible.”[58] This is the case with the parable of the sower, which describes a farmer sowing seed across varied terrain. Some lands upon thorns and some is eaten by birds; only that which lands on fertile ground produces a crop. As Christ later explains to his confused followers, the story is a kind of metaparable, describing how, although many people may hear his teachings, only those who are not drawn astray by temptation gain access to the kingdom of God. This elucidation is shared only with Christ’s core circle of followers: “And he said to them,/ ‘To you has been given the secret of the/ kingdom of God, but for those outside, every/ thing comes in parables; in order that/ “they may indeed look, but not perceive, and may indeed listen, but not/ understand;/ so that they may not turn again and be forgiven.”’”[59] As Landy points out, Christ in this narrative purposefully makes it difficult for the wider public to access his message. Why would he do so, and why might this model have held particular appeal for Burne-Jones?[60]

Landy suggests that the reason for this lack of clear meaning may be that the spiritual work lies in the act of understanding: to be simply given the explanation is not enough. He writes, “Salvation depends on our ability to think parabolically, to dwell in metaphors, since to dwell in metaphors is to consider the entire sensory realm as a shadow-forthing of a higher realm of existence, and thus to see the world from God’s point of view.”[61] Saint Augustine (354–430) had expressed a somewhat similar view, writing that the obscurity of the parables “was divinely arranged for the purpose of subduing pride by toil, and of preventing a feeling of satiety in the intellect.”[62] Like a parable, The Flower Book relies on the ability to understand metaphor (and sometimes the metaphor for the metaphor). Something is always standing in for something else: a flower name for a myth, a myth for a lived experience or universal truth. Burne-Jones may have been reticent to tell people “what they ought to think” because to do so was to give the game away, to rob the viewer of the moment of metamorphosis.

The centrality of the viewer’s experience to The Flower Book project is further evidenced by the repetition of the tale of the Three Kings in its watercolors. The Three Kings appear twice, in Traveller’s Joy (see fig. 1) and Star of Bethlehem (see fig. 18). The latter shares its title with a large-scale watercolor of the same subject by Burne-Jones (1885–90, Birmingham Museum, Birmingham). In The Flower Book’s Star of Bethlehem, the Three Kings stand at disparate points in a rocky landscape, as if beginning the journey from their different kingdoms, faces turned toward a guiding angel in the foreground who carries a pulsing, gold star. In Traveller’s Joy, the kings emerge from the mountainous terrain, gazing toward the manger in the distance, at which they will soon arrive. Wolk Rager writes that Burne-Jones may have been drawn to the Three Kings as an analogy for “the viewer as witness, an active participant in the transformative aesthetic vision.”[63] The journey, surely, is key to this vision—to arrive is to understand. The Flower Book challenges the viewer not only to see but to perceive.

In the original Flower Book Burne-Jones left no descriptions of the watercolors beyond their titles. As it was a work in progress, he may have intended to do so later, but there is no evidence to indicate this. In the 1905 facsimiles commissioned by Lady Burne-Jones, each illustration is accompanied by a brief explanation. Whoever wrote these descriptions (almost certainly Georgiana Burne-Jones herself) perhaps did so with the thought that, like the disciples, the average reader was going to need some help deciphering the images. Lady Burne-Jones may have filled in explanations based on her extensive knowledge of her husband’s favored motifs or from memories of previous conversations with him. Naturally, images such as Wake Dearest are perfectly legible without the accompanying text. Others may have been more difficult for the viewer to understand, such as Arbor Tristis (fig. 23). This starkly beautiful roundel takes its name (which means “sad tree” in Latin) from night-flowering jasmine. It depicts the base of a tree atop a desolate mound, a cityscape in the background eerily blue amid a sunset sky. The first impression is not so much one of narrative but of loneliness: the tree is bare, almost dead in appearance, and seems separated by some distance from the lighted city windows which dance in the background. In the Piazza version, the caption reads: “The foot of the Cross.”[64] It is possible, but not probable, that the viewer would reach this Christian interpretation after having seen only the image and read its title. While Arbor Tristis suggests a certain lifelessness and sense of abandonment, fitting for the death of Christ, its unusually magnified, ground-level perspective on the Cross (or tree) makes it difficult to recognize this most identifiable of Christian symbols. Without the benefit of the caption, the viewer risks misunderstanding the image or making up their own narrative about it. As Müller wrote, “there is danger of mythology.”[65] Like the parables in the Gospel of Mark, the facsimile of The Flower Book is torn between mystery and elucidation, the desire to let metaphors lie and to be the one true and authoritative narrative.

Burne-Jones may have found this tension more trying than he let on. He completed Ladder of Heaven (fig. 24), an image of a winged female figure holding a flowering branch while ascending a rainbow, in late 1882. It is possible that the title refers to the perennial bloom called Jacob’s Ladder (also illustrated in The Flower Book), a variety of which is known as Stairway to Heaven, but this is not clear.[66] Unlike the long, bird-like wings of Cupid and the angels, the protrusions on this figure’s back have the shape and translucency of butterfly wings. Burne-Jones wrote to Lady Leighton Warren, “I shouldn’t like to be cross-examined about the person going up the rainbow—pagans like Mallock (who as you will observe, is unfit to be laid on a drawing room table) may call it Iris. But Christians like you & me will have it be a soul—and it shall go up to the top of the rainbow & never come down the other side.”[67] Here he is likely harnessing comparative mythology to make a joke: William H. Mallock (1849–1923), far from being a pagan, was a High-Church Anglican.[68] What is most interesting is the inherent contradiction in Burne-Jones’s words: he insists that he “shouldn’t like to be cross-examined,” but then goes on to provide the desired information anyway. Like a prophet, Burne-Jones prided himself on reticence, and on giving away just enough information. In this sense he is like the Barber of The Arabian Nights, whose tale he read with Ruskin early in their acquaintance.[69] It is the Barber’s inclination toward silence which is a sign of his godliness, but conversely he demonstrates this quality through storytelling: “Now I will relate to you an event that happened to me, that ye may believe me to be a man of few words.”[70] This statement could practically be taken as Burne-Jones’s modus operandi in The Flower Book.

Myth, Parable, and Interpretation

If the images in The Flower Book do in fact represent parables, this suggests not only that they do hold meaning but also that there is only one true interpretation of that meaning. We might further explore this possibility through the field of hermeneutics. The early nineteenth-century theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1786–1834) viewed the New Testament as authored by God and mediated through human writers. While a single, correct interpretation might be found for a biblical parable, he found this not to be the case for myth, “because it cannot originate in one individual.”[71] The myths of Burne-Jones are perhaps an exception to this rule, as his process of merging an image’s title and its story requires the work of a single mind to complete the transition, one which in Müller’s mythography took place over thousands of years. The “forgotten poems” are transformed not by generations of storytellers but by the processes of Burne-Jones’s imagination alone. It might be said that the images of The Flower Book are mythic in their structure but parable-like or prophetic in their intention.

Taking this to be true, a singular interpretation might be possible. Just as Lévi-Strauss found meaning in myth by layering similar events, the hermeneutical scholar Hans-Georg Gadamer maintained that there is a “circular movement of understanding” which takes place between part and whole.[72] He wrote that from a Reformation perspective, scripture is not intelligible in its every individual passage, because “the whole of Scripture guides the understanding of individual passages: and again this whole can be reached only through the cumulative understanding of individual passages.”[73] Meaning in The Flower Book seems to operate in a similar way. Arbor Tristis, a scene of desolation at the foot of the Cross, means something more when juxtaposed with the scenes of the Three Kings and the Annunciation elsewhere in the book, which remind the viewer that the story of Christ’s death began with his miraculous birth. It means still more when juxtaposed with Ladder of Heaven: here the prophecy of life after death seems to find itself fulfilled. Arbor Tristis is not an ending, as its sunset backdrop suggests, but rather one dark episode in an ultimately hopeful and redemptive epic. The repetition of themes not only draws attention to particular motifs of quests, awakenings, and births but also to the greater story that may be assembled from these pieces. Above all, The Flower Book seems to be a story of the cyclical nature of life. As each of its tales speaks to resurrection after death—the Sleeping Beauty, the life of Christ, the angel who awakens the spring—these stories “pil[ed] . . . up one over the other,” in the words of Lévi-Strauss, suggest an unending narrative, circular like a watercolor roundel, in which rebirth plays out again and again among different settings and characters.

When examined through this lens, meaning in The Flower Book is not present “in every line he drew” but rather in the book as a whole and the ways in which the individual images work within it. Naturally, as with all acts of interpretation, complete understanding remains unachievable. Schleiermacher, while recognizing this reality, was not deterred by it. Even when some mystery surrounding the meaning remains, understanding can still be brought about by degrees, which he found preferable to allowing a total collapse of meaning.[74] In the catalogue for the Arts Council of Great Britain exhibition on Burne-Jones in 1975, John Christian and Penelope Marcus remarked that “ultimately Burne-Jones believed that a picture should present a mystery because nothing less would be a valid comment on life.”[75] In The Flower Book watercolors, as in life, discovery is not made all at once but rather by slow progression, repetition, and the retracing of steps. Like reading a parable, paging through The Flower Book becomes a kind of spiritual work, a project perhaps equally as rewarding as Burne-Jones’s process of making it.

Conclusion

In this article, I have demonstrated the possibility that The Flower Book is an exercise in myth and parable—and above all, an exercise in the creation of meaning and its interpretative limits. Müller’s mythographic “diseases of language” theory, which cites metaphors as the origin of myths, may be the key behind the transformation of meaning—from flower names to fairy tales—which serves as the work’s system. Like an epic myth, The Flower Book is further defined by the repetition of key events and themes. When examined through a structuralist lens, this repetition can be understood as creating meaning by emphasizing the book’s essential motifs, which unite stories of different origins, such as the theme of rebirth in Briar Rose and Brynhilde. These essential motifs also interact with one another, as in Arbor Tristis, whose themes of death and loss create a larger, epic myth centered on renewal when paired with Wake Dearest, Flame Heath, and others. However, as Burne-Jones’s own writings suggest, he intended this epic myth to not be fully decipherable from the images. Rather, like an unfolding parable, The Flower Book engages its viewer in an experience both scholarly and spiritual, in which interpretation is achieved only by degrees.

Even from this partial understanding something is gained. The figure of Iris in Ladder of Heaven, ascending steadfastly up the rainbow to the heavens, brings to mind Landy’s phrase: “to dwell in metaphors is to consider the entire sensory realm as a shadow-forthing of a higher realm of existence, and thus to see the world from God’s point of view.” Iris’s upward path is not easy: she climbs with an alpinist’s gait, her right knee bent at a sharp angle as her foot presses against the rainbow’s steep ridge. She has not yet reached the end of her journey, but already the view from above yields some rewards: a glorious landscape of rolling hills and trees and even the edge of a lake. To “read” The Flower Book is not to see the world from the height of the rainbow, from God’s point of view, but to labor upward, and to perhaps catch glimpses of a higher meaning.

Acknowledgments

My sincere thanks to Caroline Arscott at the Courtauld Institute of Art and to the team at NCAW. I am grateful to the Cheshire Record Office, the British Museum, the British Library, and Wellesley College Art Library for assistance with primary and secondary sources.

Notes

[1] Edward Burne-Jones, The Flower Book (London: Henry Piazza for the Fine Art Society, 1905), n.p.

[2] Burne-Jones corresponded extensively with Eleanor, Lady Leighton Warren, during the years he worked on The Flower Book. The wife of a conservative member of Parliament, she had met Burne-Jones in London in 1877. Her horticultural aid extended to sourcing briars for Burne-Jones to study for the Briar Rose series. For more details about the correspondence, see “Antiques, Antiquities, and Textiles,” lot 473, November 8, 2018, Dominic Winter Auctioneers, accessed May 28, 2023, https://www.dominicwinter.co.uk/. Lady Leighton Warren’s brother, John Warren, 3rd Baron Tabley (1835–95), was a poet as well as a botanist. After his death, Leighton Warren oversaw the publishing of his book on local plants, Flora of Cheshire (1899). Several of the common names of The Flower Book are listed in this volume. John Warren, The Flora of Cheshire, ed. Spencer Moore (London: Longmans, Green, 1899). For biographical information, see “Warren, John Byrne Leicester (1835–1895),” Representative Poetry Online, University of Toronto Libraries, 2003, https://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/.

[3] Edward Burne-Jones to Lady Leighton Warren, August 8, 1888, NRA 3636 Leicester-Warren, Title deeds and estate papers, family and personal papers, Leicester-Warren Family of Tabley House, Cheshire Archives and Local Studies, Cheshire Record Office, Chester, UK (hereafter NRA 3636 Leicester-Warren).

[4] See the entry for the plant known as Traveller’s Joy (Clematis vitalba), Woodland Trust, accessed July 7, 2023, https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/. See also John Ruskin, The Art of England (New York: Wiley and Sons, 1884), 37.

[5] Penelope Fitzgerald, Edward Burne-Jones (London: Michael Joseph, 1975; Gloucester: Sutton Publishing, 2003), 195–96, https://archive.org/.

[6] John Christian and Penelope Marcus, eds., Burne-Jones: The Paintings, Graphic and Decorative Work of Sir Edward Burne-Jones, 1833–1898, exh. cat. (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1975), 89, https://archive.org/.

[7] Stephen Wildman and John Christian, Edward Burne-Jones: Victorian Artist-Dreamer, with essays by Alan Crawford and Laurence des Cars, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), 285–86.

[8] Fitzgerald, Edward Burne-Jones, 196.

[9] Fitzgerald, Edward Burne-Jones, 196. Historically, The Flower Book watercolors have been given the dates that span the project as a whole (1882–98). Here, I have used Burne-Jones’s correspondence with Lady Leighton Warren to date the individual watercolors with greater accuracy, although, in some cases, this still allows for a difference of several years. However, these revised dates may be useful for understanding the progression of The Flower Book as a whole as well as how the individual roundels relate chronologically to Burne-Jones’s other work.

[10] Burne-Jones, The Flower Book, n.p.

[11] See Antonius de Cocq, “Andrew Lang: A Nineteenth Century Anthropologist” (PhD diss., University of Utrecht, 1968), 86; and Max Müller, Lectures on the Science of Language Delivered at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, 2nd ser. (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green, 1864), 499.

[12] Quoted in Dinah Birch, Ruskin’s Myths (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), 40–42.

[13] See Birch, Ruskin’s Myths, 40–42.

[14] Müller, Lectures on the Science of Language Delivered at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, 358.

[15] Max Müller, Comparative Mythology: An Essay (London: Routledge, 1909), 71–73, 94. Müller’s essay was first published in Max Müller, Montague Bernard, and George Butler, Oxford Essays 1856 (London: J. W. Parker, 1856).

[16] Müller, Comparative Mythology, 82, 118.

[17] Müller, Comparative Mythology, 91.

[18] Birch, Ruskin’s Myths, 40.

[19] Like Müller, Rhys relied on etymological research. He believed that the sun held special significance for early peoples and that it played a key role in mythology and the development of mythological personages. In Studies in the Arthurian Legend, he suggested that the etymology of Galahad’s name demonstrated that he was one such “Solar Hero.” John Rhys, Studies in the Arthurian Legend (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1891), 13.

[20] Edward Burne-Jones to Lady Leighton Warren, April 7, 1891, in NRA 3636 Leicester-Warren.

[21] Andrea Wolk Rager, “‘Smite This Sleeping World Awake’: Edward Burne-Jones and The Legend of the Briar Rose,” Victorian Studies 51, no. 3 (Spring 2009): 443, https://www.jstor.org/ [login required].

[22] Fortunée de Lisle, Burne-Jones (New York: Dodge, 1904), 90, https://archive.org/.

[23] Andrea Wolk Rager, The Radical Vision of Edward Burne-Jones (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2022), 60.

[24] Georgiana Burne-Jones, Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, vol. 2 (New York: Macmillan, 1906), 118.

[25] John Ruskin, Proserpina: Studies of Wayside Flowers, vol. 1 (London: George Allen, 1897), 64.

[26] Edward Burne-Jones, The Flower Book, n.p.

[27] Edward Burne-Jones, quoted in Robert de la Sizeranne, “In Memoriam: Sir Edward Burne-Jones, Bart., A Tribute from France,” The Magazine of Art (London: Cassell, 1898), 519, https://archive.org/.

[28] Burne-Jones and Morris met as students at Oxford and shared an intensively collaborative relationship in their artistic careers. While Burne-Jones is primarily remembered as a painter, he completed many designs for engravings, stained glass, and decorative art for Morris’s artistic endeavors, such as the home-goods producer Morris & Company and the Kelmscott Press printing company.

[29] Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folktale, 2nd ed., ed. Louis A. Wagner, trans. Laurence Scott (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1968), 90. First published in Russian in 1928.

[30] Propp, Morphology of the Folktale, 112–13.

[31] Georgiana Burne-Jones, Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, 2:53.

[32] Morna O’Neill, Walter Crane: The Arts and Crafts, Painting, and Politics, 1875–1890 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 150, 156–57.

[33] Caroline Arscott, William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones: Interlacings (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 109.

[34] Charlotte Gere, “Portraits,” in Edward Burne-Jones, ed. Alison Smith, exh. cat. (London: Tate, 2018), 157.

[35] Wildman and Christian, Edward Burne-Jones, 161.

[36] Elizabeth Prettejohn, “The Series Paintings,” in Smith, Edward Burne-Jones, 180.

[37] Wolk Rager, Radical Vision of Edward Burne-Jones, 3.

[38] Arscott, William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, 118.

[39] Edward Burne-Jones, The Flower Book, n.p.

[40] Christian and Marcus, Burne-Jones, 30.

[41] “Design for the Annunciation Mosaic for the American Episcopal Church, St. Paul’s within the Walls (the American Church in Rome), Italy,” Burne-Jones Catalogue Raisonné, https://www.eb-j.org/.

[42] Alexis-François Rio, quoted in Georgiana Burne-Jones, Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, 2:141.

[43] “Three Studies for ‘The Beguiling of Merlin,’” Tate, September 2004, https://www.tate.org.uk/.

[44] Patrick Fairbairn, Typology of Scripture, vol. 1 (Philadelphia: Smith and English, 1854), 19.

[45] George Landow, Victorian Types, Victorian Shadows: Biblical Typology in Victorian Literature, Art, and Thought (Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1980), 50.

[46] Landow, Victorian Types, Victorian Shadows, 40.

[47] Fitzgerald, Edward Burne-Jones, 196.

[48] Claude Lévi-Strauss, Structural Anthropology, trans. Claire Jacobson and Brooke Grundfest Schoepf (London: Allen Lane, the Penguin Press, 1969), 208. First published in French in 1958.

[49] Claude Lévi-Strauss, Myth and Meaning, (1978; repr., London: Routledge, 2001), 40–42.

[50] Florence Boos, “‘The Banners of the Spring to Be’: The Dialectical Pattern of Morris’s Later Poetry,” English Studies: A Journal of English Language and Literature 81, no. 1 (2000): 16, https://www.tandfonline.com/ [login required].

[51] Elizabeth Prettejohn, Modern Painters, Old Masters: The Art of Imitation from the Pre-Raphaelites to the First World War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017), 163–66.

[52] Prettejohn, Modern Painters, Old Masters, 163.

[53] Lévi-Strauss, Structural Anthropology, 209.

[54] Edward Burne-Jones to Lady Leighton Warren, June 21, 1886, in NRA 3636 Leicester-Warren.

[55] Georgiana Burne-Jones, Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, 1:297.

[56] Edward Burne-Jones to Lady Leighton Warren, October 28, 1882, in NRA 3636 Leicester-Warren.

[57] The verses quoted from the biblical books of Isaiah and Matthew come from the New Revised Standard Version with the Apocrypha.

[58] Joshua Landy, How to Do Things with Fictions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 45–47.

[59] Mark 4:11–12 (New Revised Standard Version with the Apocrypha).

[60] Landy, How to Do Things with Fictions, 47.

[61] Landy, How to Do Things with Fictions, 59–62.

[62] Augustine, On Christian Doctrine, in Four Books (Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library, n.d.), 24, http://www.ntslibrary.com/.

[63] Wolk Rager, The Radical Vision of Edward Burne-Jones, 212.

[64] Edward Burne-Jones, The Flower Book, n.p.

[65] Müller, Lectures on the Science of Language Delivered at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, 358.

[66] “Polemonium reptans ‘Stairway to Heaven,’” Gardenia, accessed July 7, 2023, https://www.gardenia.net/.

[67] Iris was the ancient Greek goddess of the rainbow and the messenger of the Gods.

[68] The novelist W. H. Mallock’s Tory views and antisocialist writings placed him in a distinctly different political camp from Burne-Jones. His novel The New Republic satirized the aestheticist art critic Walter Pater (1839–94). See “Mallock, William Hurrell,” in The Oxford Companion to English Literature, ed. Dinah Birch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), https://www.oxfordreference.com/ [log-in required].

[69] Georgiana Burne-Jones, Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, 1:300.

[70] E. W. Lane, Lane’s Arabian Nights, vol. 1 (London: Jarrold and Sons, 1915), 533. First published in 1840.

[71] Friedrich Schleiermacher, Hermeneutics and Criticism, ed. and trans. Andrew Bowie (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 16. First published in German in 1838.

[72] Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, 2nd rev. ed., trans. and rev. Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall (London: Continuum, 2004), 292. First published in German in 1960.

[73] Gadamer, Truth and Method, 176.

[74] Andrew Bowie, introduction to Schleiermacher, Hermeneutics and Criticism, xxvi.

[75] Christian and Marcus, Burne-Jones, 48.