Domesticating Robespierre: The Victorian Historical Imagination in William Henry Fisk’s French Revolution Paintings

by Alice C. M. KwokAlice C. M. Kwok is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. She writes about the role of art and literature in mediating memories of French history during the long nineteenth century. Her dissertation examines the revival of Old Norse studies in France between the Restoration and World War I.

Email the author: alice.main270[at]gmail.com

Citation: Alice C. M. Kwok, “Domesticating Robespierre: The Victorian Historical Imagination in William Henry Fisk’s French Revolution Paintings,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 2 (Autumn 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.2.5.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

At London’s Royal Academy Exhibition of 1863, long-time exhibitor and established British genre painter William Henry Fisk (1827–84) displayed two scenes taken from the French Revolution. One was fairly standard; the other was wildly unexpected.

Royal Academy Exhibition item number 620, Fisk’s The Old Noblesse in the Conciergerie (fig. 1) reflected long-established British attitudes toward the Revolution’s aristocratic casualties. It depicted a crowd of elites locked in the titular prison awaiting their date with the guillotine.[1] Some figures face their doom with moving pathos; see, for example, the anguished couple in the left foreground or the priest and his two female congregants hiding in the shadows at the far right. Most of the painting’s actors, however, conform to the exhibition catalogue’s comment that despite their dire circumstances, the incarcerated nobles “carried on the gay life of the court and the chateau with all their national vivacity. . . . Musical parties, coquetting, and gambling were their occupation all day, which they pursued with an eagerness in proportion to the trouble they sought to drown.”[2] Fisk’s tableau drew on seven decades of British fascination with the plight of the French nobility during the Revolution.[3] Since the first flight of the émigrés (emigrants) in 1789, English politicians, philanthropists, and novelists had been sanctifying these high-born victims as martyrs in order to demonize the revolutionaries. At the same time, however, Anglo-Saxon observers obsessed over the perceived endurance of an aristocratic frivolity they imagined as uniquely French. They swapped stories of impoverished émigrés hawking their last jewels in order to buy a new gown for a ball at Coblentz, or of fashionable ladies impeding the march of the royalist army with their vast, luxurious carriages.[4] These tales of irrepressible French levity bolstered a British national self-image of stoic rationality. Fisk thus followed a well-trodden road in gently mocking the aristocracy for blind pleasure seeking in the midst of existential peril.

Fig. 2, William Henry Fisk, Robespierre Receives Letters from the Friends of His Victims, Threatening Him with Assassination, 1863. Oil on canvas. Musée de la Révolution Française, Vizille. Artwork in the public domain; image courtesy of Musée de la Révolution Française.

Royal Academy Exhibition item number 353, however, offered a strikingly unanticipated take on the Revolution.[5] Fisk’s Robespierre Receives Letters from the Friends of His Victims, Threatening Him with Assassination (fig. 2) portrayed the so-called Incorruptible—Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (1758–94)—alone in his room, perusing correspondence, nearly enveloped by an overabundance of flowers.[6] Fisk did not build on any traditional idioms for representing the most notorious member of France’s Committee of Public Safety. He did not sketch a major revolutionary flash point or incorporate other revolutionary actors. Even more surprisingly, this canvas refuses to wear its politics on its sleeve. Unlike previous portraits of Robespierre, item 353 steadfastly declines to take a clear stand. While there are certainly gestures towards condemnation—the title, Robespierre’s surly expression, the image of the guillotine tucked away at the far-left edge of the canvas—the spectator is nonetheless hard-pressed to recognize the bloodthirsty boogeyman of British historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle’s (1795–1881) histories in this domestic, floral tranquility. Fisk has created a stubbornly ambivalent scene, one that resists easy political dichotomies. The sheer idiosyncrasy of the canvas thus compels us to ask the question: Why would someone paint Robespierre in this way? Why is this image so difficult to read? And just what did the painter hope to accomplish with it?

In composing this picture, Fisk brought together two currents that marked the cultural landscape of Britain in the midcentury. The first was an evolving understanding of the French Revolution.[7] In the immediate aftermath of the Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, Britain was united by its unqualified antipathy towards the Revolution. Indeed, Linda Colley has argued that this antipathy proved instrumental in congealing a common British identity.[8] However, thanks to the largely peaceful July Revolution of 1830 and the fight for the Reform Bill of 1832, certain Whigs began to look favorably on the aspirations of 1789.[9] They claimed that the ideals of the early Revolution were admirable, even worthy of emulation, and blamed subsequent violence on the monarchists who vainly sought to halt the march of progress. The Revolution of 1848 accelerated this intellectual metamorphosis among both liberals and radicals. While a hard kernel of conservatives continued to frame the French Revolution as an unmitigated bloodbath of tragic proportions, according to French historian Fabrice Bensimon, “this ultra-Tory interpretation became more and more marginal. . . . If the French Revolution still occupied, by the end of the nineteenth and in the twentieth centuries, an important place in British culture, it was in a banal, euphemistic way, far distant from the real fears that it evoked during the forty years that followed 1789.”[10] Robespierre Receives Letters hints at this change through its softened portrayal of Robespierre. Yet, it simultaneously reacts against the hagiography of the Incorruptible promulgated by some nineteenth-century British Chartists, notably Bronterre O’Brien.[11] By forging a middle path between Carlyle’s hatred and O’Brien’s hero-worship, Fisk helped banalize Robespierre and the Revolution.

At the same time, a different transformation was rocking the art world. The Victorian era witnessed the inauguration of what Roy Strong has termed the “Intimate Romantic,” or popular depictions of historical protagonists in domestic settings.[12] Instead of capturing the famous figures of bygone ages at memorable political turning points, exponents of the Intimate Romantic showed them en famille (at home). These sentimental portraits, inspired by the works of Sir Walter Scott and other historical novelists, married the traditional subjects of history painting to the stylistic conventions of genre. In his representation of Robespierre, Fisk drew heavily on this new visual trend.

I contend that Fisk transposed the Incorruptible into a genre scene in order to render him politically illegible but artistically legible. This unique objective explains why the painting cannot be easily read as either pro- or anti-Robespierre. Instead of viewing the Revolution through the lens of ongoing ideological clashes, Fisk proposed appreciating it on aesthetic terms, as a colorful anecdote. Both Robespierre Receives Letters and The Old Noblesse in the Conciergerie embrace whimsy, refusing to take the Revolution too seriously. Rather, they foreground the incongruities and emotional vagaries of their protagonists. They ask the audience to consider the period not as a political problem but as an amusing melodrama. Robespierre is less menacing than picturesque. Revolutionary violence ceases to be a pressing calamity and becomes an exhilarating spectacle capable of titillating all observers on a shared level. Fisk insists that the Revolution should not divide us but entertain us.

What intellectual work does this startling reconceptualization perform? By deracinating Robespierre from the political debates that had embroiled his memory, Fisk participates in that distinctly British project of mobilizing art to dissipate political conflict. Scholars have demonstrated how nineteenth-century painters used their images to smooth and soothe fissures in the body politic by imagining an unproblematic British identity grounded in a shared appreciation for the beautiful.[13] This confidence in the power of a certain Victorian sensibility to unify and conciliate the public reflected the proud (and selectively forgetful) English self-conception as a nation gloriously free of revolution. A brand of British exceptionalism credited the nation with a uniquely flexible constitution and pacific populace that supposedly permitted gradual progress without violent rupture.[14] This exceptionalism of course underwrote conservative efforts to stifle working-class, feminist, and colonized demands for equitable change.

In this article’s two parts, I will disentangle the visual contradictions that obscure Robespierre Receives Letters. Specifically, I will trace Fisk’s dichotomous mobilization of the domestic Robespierre. First, I will highlight the ways in which posing Robespierre in this embowered garret effeminized him, foregrounding his violence, hysteria, and monstrosity. Then, I will demonstrate that this pose simultaneously and paradoxically vindicated him on the grounds of his passion, love, and humanity. The fundamentally inconsistent portrayal frustrates interpretation—which was precisely the artist’s intent.

Fisk’s painting is politically unintelligible because he wanted the Revolution to be politically unintelligible. The image seeks to neutralize Robespierre and the Terror as rallying points capable of dividing the British public along ideological lines. It thus contemplates, and endeavors to instantiate, a politically quiescent populace united by a common emotionalism. Unique among depictions of the Revolution, it rejects partisanship and embraces instead a pure aestheticism capable of stabilizing factional rifts. Ironically, of course, this tentative thawing of hostility toward the Revolution served the profoundly antirevolutionary goal of convincing the British people that their special national quality was to eschew progressive struggle. Consequently, careful attention to this painting helps resolve that enduring historiographic puzzle: how did Britain escape the violent mass revolutions of the long nineteenth century?

William Henry Fisk: The Man

William Henry Fisk was born in 1827 to the prolific history painter William Fisk (1796–1872).[15] His father’s eldest son and pupil, William Henry achieved success in several arenas. He first exhibited his work in 1846, and in 1849 he was invited to Balmoral to paint watercolors of the countryside.[16] Four of his landscapes were selected for Queen Victoria’s souvenir album.[17] In 1850, he made his debut at the Royal Academy, where he quickly specialized in historical and biblical scenes.[18] He was appointed anatomical draughtsman to the Royal College of Surgeons, where he produced many memorable colored-pencil drawings of the musculature of birds and chimpanzees.[19] He also worked as an instructor, not only teaching drawing and painting at University College School in London but also lecturing to crowds throughout the country and organizing private lessons for groups of women artists.[20] As a tribute to his institutional success, in the 1860s Fisk was commissioned to contribute two designs to the Kensington Valhalla.[21] A series of mosaics depicting great artists of the past, the Valhalla was intended to grace the arcade niches that encircled the upper level of the South Court of the Kensington Museum in London. Fisk’s portraits of Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455) (fig. 3) for the Valhalla now reside at the Victoria and Albert Museum. When he died in November 1884, his obituary was published in the Athenaeum.[22] In his brief fifty-eight years, Fisk built a modest but acknowledged home for himself at the heart of Britain’s artistic establishment.

Despite this footprint in the records of the Victorian art world, William Henry Fisk’s political affiliations are an enigma, and I have not been able to locate his personal papers. As a result, I cannot rely on many of the most useful tools art historians would typically employ to decode a work’s ideological message. Fisk’s paintings themselves are the best and indeed the only keys to his political leanings, and they are far from textbook expressions of partisanship. The ambiguity around Fisk produced by this absence of sources both explains and is exacerbated by the lack of recent scholarship on him. To date, I know of no dedicated study of his life and oeuvre. Though he was respectably successful and well-attested in the universe of nineteenth-century British art, Fisk—and his paintings—remain something of a mystery.

Fisk Condemns Robespierre

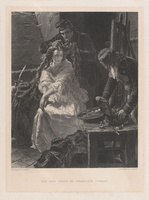

When Fisk set out to paint Robespierre, he encountered strong existing conventions. By 1863, a clear canonical British interpretation of Robespierre had emerged. This interpretation owed its origins to the so-called father of modern conservatism, Edmund Burke (1729–97). Burke described the Revolution as a horror show of human depravity run amok.[23] His condemnation of the revolutionaries themselves had a long afterlife. Though nineteenth-century historians such as Archibald Alison (1792–1867), William Smyth (1765–1849), and Carlyle had divergent attitudes towards the Revolution as a whole, they were united in their hatred of Robespierre.[24] This historiography unsurprisingly colored the artistic world, which was not kind to the Revolution or its leaders. The enduring British iconography of the Revolution was set down by the cartoonist James Gillray (1756–1815), whose contemporary caricatures of the Jacobins portrayed them as hateful, bloodthirsty demons (fig. 4). Gillray’s pictorial influence lived on well after his death in 1815. For example, in 1852, Edward Matthew Ward (1816–79) submitted to the Royal Academy Charlotte Corday Led to Execution. Ward depicted a demoniac Robespierre leering gruesomely at the lovely young martyr while his massive hound threatened to maul her. Ward was a devoted apologist of Jean-Paul Marat’s (1743–93) assassin. He depicted another scene from Corday’s final hours in La Toilette des Morts (fig. 5), which also hung at the Royal Academy Exhibition in 1863. It showed the beautiful Corday demurely submitting to a scowling Jacobin cutting her hair in preparation for the guillotine; Ward’s Toilette must have thrown the idiosyncrasy of Fisk’s Robespierre into even sharper relief.

Indeed, Fisk’s canvas marks an incontrovertible departure from established norms in the British representation of the Incorruptible. His whimsical domestic scene could not be more at odds with the usual vision of a deranged sadist, “sea-green . . . converted into vinegar and gall.”[25] Nevertheless, at first glance the painting betrays the same anti-Robespierrist bias espoused by Burke and Carlyle.[26] The paratext surrounding the image was unequivocally condemnatory. The work’s full title, Robespierre Receives Letters from the Friends of His Victims, Threatening Him with Assassination, immediately branded Robespierre with responsibility for the state violence of the Terror. It evoked the anguish of families severed from loved ones by the guillotine and the rift in the French community occasioned by Robespierre’s supposed tyranny. The catalogue for the 1863 exhibition further included a damning biblical passage to accompany the painting: “The merciful man doeth good to his own soul: but he that is cruel troubleth his own flesh. Though hand join in hand, the wicked shall not be unpunished. Proverbs xi. 17, 21.”[27] Robespierre was self-evidently the wicked in question, and he met his punishment in the Thermidor coup that ended his life.

Moreover, Fisk ensured that Robespierre’s cruelty did trouble his flesh. The figure’s eyes are deeply hooded, staring abstractedly into the middle distance, ruminating on bloodshed. The hard line of his frown, his pursed lips, and the sharp jut of his jaw telegraph a barely restrained violence. The crumpled papers on the floor beside his chair gesture backward in time toward a moment of potential eruption. Did he fly into a fit of rage while reading an earlier letter, then wad it up and cast it away? These clues reveal an unspoken depth of feeling that the subject keeps tightly locked away. The Spectator certainly read Robespierre’s visage this way, noting “the reference to the passage in Proverbs . . . is justified by the livid hue and red, unhealthy-looking eyes of the timid tyrant who maintained the Reign of Terror.”[28] Other reviewers amply praised Fisk’s mingling of emotional torment and malevolence in Robespierre’s face, often finding it the best thing in the image. The Morning Post wrote: “the work has much vigor and truthfulness of composition, and the ferocity of Robespierre’s nature is intimated with alarming distinctness by the cruel and remorseless expression of his thin, pale face, with its scowling brow, its white, compressed lips, and its cold, unmerciful eyes.”[29] The Allgemeine Zeitung (Universal news) insisted that “[Fisk’s] Robespierre succeeds admirably, and he has happily mixed in the physiognomy an understanding of the contemptuousness that dismisses humanity.”[30] The Art Journal offered a similar gloss:

“Robespierre receiving Letters from the Friends of his Victims which threaten him with Assassination” (353), by W. H. Fisk, also merits passing comment for the especial care in its painting. This scourge of God, seated in a luxurious chamber, is seen reading a letter, his lips pressed together in fierce resolve, his brows knit with anger. . . . Mr. Fisk’s picture—true to the character depicted, even to the pitch of the repulsive—possesses merit.[31]

The reviewers all agreed they were looking into the face of a murderer.

The temporality of the painting further highlighted Robespierre’s crimes.[32] Though not stated explicitly, the scene is clearly meant to take place on June 8, 1794, the Festival of the Supreme Being.[33] Fisk painted Robespierre in the outfit he famously wore the day of the festival: a sky-blue coat and nankeen trousers made specially for the occasion, accessorized with the tricolor sash and plumed hat of the people’s representatives.[34] The mud caked on the soles of his shoes recalls the day’s long parade through the grubby Parisian streets and his final climactic hike up the artificial mountain constructed for the occasion at the Champ de Mars. Even the abundant flowers in the room point to the date. The withering shrub in the right-corner foreground is an azalea (Rhododendron sp.), which begins to wilt by the end of spring. The tall flowering plant behind it is a branch trellis-supported sweet pea (Lathyrus odoratus), which blooms in early summer.[35]

Why did Fisk set his scene immediately following the festival? Historian Bronisław Baczko argues that “Robespierre occupied, the day after the Festival of the Supreme Being and the law of Prairial, the position of a hinge, where were joined, in the same finality, Virtue and Terror.”[36] The festival represented the apogee of his power and his revolutionary ambitions, the high-water mark of both his own political clout and his radically transformative vision. In painting Robespierre on June 8, Fisk painted him at the height of his influence, at the one moment, if ever, France could be said to have been in his thrall. However, at the same time, scholars have long described the festival as the beginning of Robespierre’s end. This showcase of the Incorruptible’s aspirations, or his arrogance, frightened other members of the government, setting them on the path toward the Thermidorian coup that would bring Robespierre to the scaffold on July 28, 1794.[37] Thus, the festival denotes a turning point, both the zenith of Robespierre’s might and the origin of his downfall.

Fisk provided an additional indicator of his feelings towards the Incorruptible: the disintegrating revolutionary slogan inscribed on the back wall. Barely visible in the shadows behind Robespierre’s head, the three famous bywords of 1789—Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity)—are slowly rotting away. The Spectator understood this to mean that the picture’s subject had abandoned the Revolution’s ideals: “leaving the old motto of ‘Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité’ to decay on the wall behind him, [Robespierre] sets his ferocious little face towards the guillotine, which supplies unlimited food for his bloodthirstiness.”[38] The Examiner actually complained that this symbolism was a bit excessive. The reviewer noted that “there is much that is clear in design, with good painting, in Mr. W. H. Fisk’s Robespierre, but the design is laid out too obtrusively, down to the crumbling away of the inscription Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité upon the plaster of the wall.”[39] The commentators clearly understood this as an anti-Robespierre image. Indeed, they seemed to feel Fisk was browbeating his audience with an overly obvious political message.

However, Fisk did not merely tar Robespierre in the generic terms that might apply to any authoritarian. Specifically, he linked the Incorruptible to the sexually and politically anarchic female revolutionary who haunted British discourse.[40] Even more specifically, he denigrated Robespierre in sexed ways that borrowed from the Pre-Raphaelite visual lexicon. A coterie of painters and writers united by friendship as well as a shared aesthetic program, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood aimed to restore art to the purity it supposedly enjoyed before the Renaissance. Fisk was a thoroughly establishment artist, as his biography demonstrates. Nonetheless, he enjoyed dabbling in the style of the iconoclastic brotherhood. Art critic Ernest Chesneau argued that although Fisk “does not, strictly speaking, belong to the early pre-Raphaelite school,” his work ought to be classed with theirs.[41] Chesneau defined the Pre-Raphaelite project as the restoration of Truth to art through meticulous attention to detail and the rejection of the beautiful but corrupting artifice that had dominated painting since the Renaissance.[42] Chesneau saw these goals pursued in Fisk’s Last Evening of Our Lord at Nazareth, which was first displayed at the Royal Academy in 1864.[43] Chesneau encountered the painting at “the English gallery in the Champ-de-Mars in 1867,” and in it “observe[d] the same earnest desire to restore with perfect accuracy, in the most minute details, the appearance of truth. . . . They [the Pre-Raphaelites] adhere to the historical reality of events in order that they may interpret the letter and the spirit.”[44] Chesneau found the “same carrying out of minutiae . . . in the pictures of Messrs. H. Hunt, Fisk, and A. Hughes.” Indeed, he compared Last Evening of Our Lord at Nazareth at length to leading Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt’s (1827–1910) The Light of the World (fig. 6).[45] To be fair, Hunt himself detested this comparison. According to scholar George P. Landow, “Chesneau, whose conceptions of English painting were largely dependent upon the 1867 International Exhibition in Paris, annoyed Hunt by placing a minor American [sic] painter named Fisk in the Pre-Raphaelite group. The painter had decided to tell his own version of the history of Pre-Raphaelitism, and therefore he chose not to correct Chesneau’s version.”[46] Hunt wrote to John Ruskin (1819–1900) in 1884 that “for years after I had done the ‘Light of the World’ I could only pay my rent by doing tinkering. There will be enough to shew that I was independent in my course, and that ‘Mr. W Fisk,’ and some other notables, to be discovered thro M. Chesneau, were not exactly the painters whose essays were to be taken as examples of my intentions in Art.”[47] Nonetheless, when Cassell’s Family Magazine reviewed Chesneau’s book, they accepted his inclusion of Fisk in the brotherhood’s wider orbit:

The second part of “The English School of Painting” is devoted to our modern masters, leading off with the Pre-Raphaelites and their apostles. The most perfect justice is done to them and their works, beginning with Mr. Holman Hunt’s “Light of the World,” exhibited in 1855, and a far less known picture, Mr. Fisk’s “Last Evening of Our Lord at Nazareth.” A very important aspect of the early Pre-Raphaelite work is here insisted on, and that is the conflict between accuracy and faithfulness in detail, and nobility of design, but no one perhaps has ever before so clearly set forth the original aims of the first disciples of the cult.[48]

Additionally, when J. B. Manson compiled Frederick George Stephens and the Pre-Raphaelite Brothers in 1920, he included Fisk, who had done a very handsome portrait of Stephens.[49] As recently as 2016, Stefan van den Bossche classified Fisk among the forerunners of Pre-Raphaelitism.[50]

As in his Last Evening of Our Lord at Nazareth, Fisk deployed the Pre-Raphaelite hyperabundance of exacting detail when painting Robespierre. Contemporary reviewers fixated on this choice; unsurprisingly, they were not pleased about it. The Art Journal opined that “history may be dealt with, in so large and loose a way, as to lack circumstance and reality, or it may be made to chronicle an infinity of trivial detail destructive of power and grandeur. H. Fisk, in his picture of ‘Robespierre,’ in the last exhibition, fell into the latter snare.”[51] Another article from the same publication, one which otherwise praised the painting, lamented that “the whole canvas is worked up with the minuteness of a miniature, and thus the breadth and grandeur required for a historic work are frittered away in dotted detail. This is the defect.”[52] The Art Journal paraphrased this review again in a later article, complaining that “the picture is of considerable merit, but all is worked up with a minuteness of elaboration altogether destructive of the breadth and the grandeur that become an historic work.”[53] The Spectator similarly groused that the painting was “a remarkable study of character, though a little overdone with details.”[54] The establishment art-world’s hostility toward Pre-Raphaelite minutiae found a ready target in Robespierre Receives Letters. Significantly, literary scholar Gavin Budge has argued that Victorian viewers understood the “undiscriminating profusion of typological detail” and concomitant “radical decentering characteristic of Pre-Raphaelite vision . . . as a loss of masculine self-control.”[55] As we shall see, Fisk used the Pre-Raphaelite idiom to frame Robespierre as emasculated and out of control.

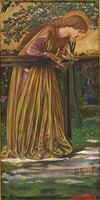

Specifically, Fisk quoted from the brotherhood’s many famous depictions of mythical maidens in his portrait of Robespierre. The first (and most striking) citation is the painting’s floral abundance. In the words of the Morning Post, the canvas “is as full of choice flowers as a conservatory.”[56] By 1863, John Everett Millais’s (1829–96) Ophelia (1852; Tate, London); Arthur Hughes’s (1832–1915) Fair Rosamund (1854; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne); Edward Burne-Jones’s (1833–98) The Blessed Damozel (fig. 7); and Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s (1828–82) Golden Water (1858; Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge), Bocca Baciata (1859; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), Hanging the Mistletoe (1860; private collection), Burd Alane (1861; private collection), and Mrs. James Leathart (1862; private collection) had cemented one of the signatures of Pre-Raphaelite portraiture: lone female sitters swathed in blossoms. William Michael Rossetti, Dante’s brother, called this trope “beautiful women with floral adjuncts.”[57] The profusion of petals engulfing Robespierre feminized him, linking him to the Pre-Raphaelite oeuvre of beautiful young medieval and literary women.

The incongruous juxtaposition of the murderous tyrant and the effeminate bouquets generates a lurking sense of unease that stalks the margins of the picture. Helen Margaret Sutherland observed a similar botanic menace in Fisk’s painting The Secret of 1858 (fig. 8), which depicts a pair of lovers hiding in a hedge while spied on by a child. Sutherland says of The Secret that “densely packed and carefully reproduced details of nature are intermingled with equally carefully painted artificial detail. Coupled with disruption of scale and . . . whimsicality and intensity which borders on insanity, this painting creates a nightmare world which is all the more threatening for its surface innocence.”[58] The disjuncture in Fisk’s work between floral splendor and hidden danger merely added another layer of sinister suspense. Such danger is telegraphed in Robespierre Receives Letters by the dying leaves that litter the floor.

Other little ornaments cluttering the room helped rewrite Robespierre’s gender. The Morning Post wrote that Robespierre “is installed in luxurious quarters. The room he occupies, which looks out upon the Seine, is elegantly furnished. . . . Costly articles are lying about in every direction.”[59] Like the flowers, these ornaments pop with the “jewelled luminosity of colour” and distinct lines sought by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.[60] Indeed, the reviewer for the Morning Post complained that “the general effect of this picture is impaired by the extravagance of color.”[61] Fisk’s obsession with exacting and exquisite detail produced a scene lush with feminine baubles. The rich teal cloth draped across the rear of the room, the paintings of various sizes arrayed on the walls, the books on the dropleaf table, the delicate vase on the desk, the shell on the windowsill, the lace curtains—all bespeak feminine preciousness.[62] Even the tricolor sash and plume, emblems of masculine authority, are rendered feminine by breezy lightness and satiny opulence. The painting’s varied textures beg to be touched, from the soft nap of feather and fabric to the cool smoothness of glass. Fisk’s plethora of trinkets was more than just a gesture toward the historicity demanded in nineteenth-century painting. The specific choice of trinkets—frivolous, dainty, sensuous—reads as the choice of a woman decorating her own space.

Fisk further feminized his subject by locating him within a quaintly domestic setting. Instead of portraying the grand ceremony of the Festival of the Supreme Being, Fisk places Robespierre at home, recovering from the exertions of the day. Victorian artists often painted middle-class women indoors in order to tacitly affirm the cult of domesticity.[63] By enclosing a woman within household walls, far from the economic and political tumult of public life, painters reified her role as the angel of the hearth. The inclusion of a window, as in Robespierre Receives Letters, juxtaposed these exterior and interior universes, underscoring the woman’s shelter (and seclusion) by emphasizing her distance from the world outside. As in Fisk’s painting, the bright airiness of the window contrasted starkly with the dark wood and stone of the room within.

Robespierre’s activities within the room also coalesce to effeminize him. He lounges—passive, horizontal, at his leisure. He does not adopt the virile, active verticality that conveyed the Victorian man’s command of his world. No door is visible in the room, suggesting that the viewer is gazing through it at Robespierre. He does not react to the entrance of the anonymous viewer—a friend? colleague? supplicant? assassin? The viewer intrudes unnoticed on Robespierre’s inner sanctum, violating his space of private thought. This transgression situates Robespierre in the receptive feminine role of being peeped at. Moreover, he is reading letters, a literary genre linked to the housebound woman. The secrétaire (secretary desk) at the left edge of the painting reinforces this link. As Dena Goodman has demonstrated, in the eighteenth century the domestic secrétaire—in contrast to the larger, masculine bureau of the business world—became the quintessential emblem of the cultivated female letter writer, a woman both educated and wealthy enough to maintain correspondence.[64] This constellation of feminine pursuits, either depicted or implied within the image, compromises Robespierre’s masculinity.

A tacit allegation of unmanaged lust also suffuses Robespierre Receives Letters. The two letters suggestively positioned on the Incorruptible’s lap mimic an erect phallus. The image of a person reading alone in their room, genitalia engorged, would immediately trigger the Victorian public’s paranoia about masturbation.[65] Fisk draws on his audience’s presumed engagement with ubiquitous anti-onanism discourse to imply that letters from Robespierre’s victims’ families arouse him. Fisk contends that Robespierre is not merely politically or intellectually monstrous but physically and sexually monstrous.

The accusation that revolutionary leaders derived sexual satisfaction from murder dates back to the legacy of the Thermidorian coup. Julia Douthwaite reports that, after the fall of Robespierre, “members of the Committee of Public Safety were rumored to reread favorite passages of [the Marquis de Sade’s] Justine during breaks from committee meetings and to return to work with their appetites newly whetted for killing.”[66] These rumors were perpetuated in part by the contemporary pornographer Nicolas Rétif de la Bretonne (1734–1806), who claimed in his autobiography Monsieur Nicolas (1794–97) that Georges Danton (1759–94) enjoyed reading “Justine, a work that drives men to cruelties . . . for the excitement it offered.”[67] Sade himself claimed in his essay “Idée sur les romans” (published in English as “Some Thoughts on the Novel”) of 1800 that the horrors of the Revolution had driven previously healthy French citizens to the deviant behavior described in his novels.[68] The royalist songwriter Louis Ange Pitou (1767–1846) perhaps most perfectly captured this conflation of sadism and Terror in his biting “La Queue, la tête, et le front de Robespierre” (“The Tail, Head, and Forehead of Robespierre”):

Robespierre’s tail is most in fashion

To soothe and still the ladies’ passion.

When his tail and his sharp blade

Penetrate some charming glade,

I hear a young virgin’s plea:

O how this knife stabs me!

This Robespierre of a tail

With blood will gorge and swell;

Squeeze it if you dare

Till pleasure wakes up there.

This murderer’s huge tail

Makes the whole world quail;

This tail bears a deep stain

Of pleasure, love and pain.[69]

Fisk was thus working within an established interpretive framework when he accused the Incorruptible of taking pleasure in death.

Like Fisk, Thermidorian satirists also charged Robespierre with effeminacy. Polemical pamphlets such as Coupons-lui la queue (Cut off his tail), Coupez-moi la queue (Cut off my tail), Rendez-moi ma queue (Give me back my tail), Renvoyez-moi ma queue (Send me back my tail), La tête à la queue (The head to the tail), Les Parties honteuses de Robespierre restées aux Jacobins (Robespierre’s private parts left to the Jacobins), and Testament de I. M. Robespierre, trouvé à la maison commune (Last will of I. M. Robespierre, found at city hall) portrayed a castrated Robespierre who had lost both his head and his penis to the guillotine.[70] These tracts lingered with vicious relish over the Incorruptible’s suffering and impotence. The loss of virility, both physical and political, translated to an assault on not only Robespierre’s policies but also his manhood.

Fisk’s accusations of effeminacy and incontinence, presaged by the Thermidorians, represented a uniquely effective attack on Robespierre and his ideological vision. In his most famous speech before the National Convention, Robespierre proclaimed that virtue was “the fundamental principle of popular or democratic government, the essential spring that supports and animates it. . . . The spring of popular government in revolution is both virtue and terror: virtue, without which terror is fatal; terror, without which virtue is impotent. Terror is nothing other than prompt, severe, inflexible justice. It is therefore an emanation of virtue.”[71] The Incorruptible himself incarnated this doctrine of the virtuous Terror. As his famed epithet implies, he was renowned for his personal character and self-discipline, believed to be free of the venal weaknesses that tarnished so many other revolutionaries. This righteous persona served as the fundamental validation of the policy of the Terror. As a virtuous man, Robespierre could be trusted not only to resist abusing the Terror’s awesome power but also to realize its transformative potential. He himself was the model citizen the Terror sought to replicate. His very existence proved that virtue was possible, and his role as the Terror’s architect imbued the system with legitimacy. However, the personification of the Terror in one man left it vulnerable to attack through that man.

Historian Joan Scott famously asserts that during the Revolution, the rights-bearing individual who composed the contractual, democratic nation-state was simultaneously conceived as “the abstraction of a genderless political subject” and embodied as a heterosexual white man.[72] Opposition to women’s political participation relied upon the representation of women as physically “saturated with their sex,” totally filled and determined by it, while men’s sex was naturalized.[73] Women’s gender made them fluid, hysterical, changeable, and generally unreliable as the constituent basis of a republic. Portraying Robespierre as effeminized sapped his right to govern. By calling into question Robespierre’s normative masculinity and sexual morality, Fisk (and the Thermidorians) undermined the very core of his claim to authority.

Or so it seems, at first.

Fisk Rehabilitates Robespierre

The middle of the nineteenth century witnessed in Britain the flourishing of the Intimate Romantic style in history painting. Strong defines this style as “paintings which take as their subject-matter personal, domestic glimpses of earlier ages, the great [individuals] of the past caught informally,” or, more colorfully, “glimpses of the private lives of the great recorded as though we looked not through an archway into the past, but through a keyhole.”[74] Notable examples of this prolific category include Frederick Goodall’s (1822–1904) An Episode in the Happier Days of Charles I (fig. 9), John Callcott Horsley’s (1817–1903) Lady Jane Grey and Roger Ascham (1853; private collection), and John Everett Millais’s Boyhood of Raleigh (1870; Tate, London). Though frequently displayed on the walls of the Royal Academy at the time, Intimate Romantic paintings have since been largely shunned by art historians as intellectually and stylistically trite. However, Strong argues that they performed important ideological work in their day. Not only did they affirm the Victorian cult of domesticity, “these scenes and their heroes were selected to inspire calm, even complacency, with regard to the present. They gave expression and substance to the all-pervasive Whig interpretation of history as progress. . . . They were aimed at kindling patriotic pride and moral virtue in the minds of onlookers, and a fear of revolution. In short, they were history as cast in the mental mould of the post-Reform-Bill electorate.”[75]

Strong demonstrates that this artistic idiom successfully rewrote controversial figures from British early modernity as unproblematic embodiments of domestic virtue. Charles I (1600–49), the king who lost his head in the English Civil War, became merely an “ideal husband and father . . . the historical prototype of the middle-class domestic happiness” valorized by the nineteenth-century bourgeoisie.[76] Jane Grey (1537–54) and even Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–87)—religious and factional opposites as they may have been—found niches in the “Victorian pantheon of perfect womanhood,” painted as meek, sensitive, devoted women assailed by hostile forces from outside the walls of their cozy mansions.[77] Safely in the distant past, these erstwhile flash points of political discord could be recovered as romantic emblems of a lost era of heroic—but comfortably bourgeois—virtue.

Although Robespierre was both French and less-than-a-century dead when Fisk painted Robespierre Receives Letters, making him an unlikely candidate for Intimate Romantic treatment, Fisk nonetheless trained this fashionable lens on the Incorruptible. By painting him in the Intimate Romantic idiom, Fisk suggested that Robespierre, too, was a virtuous innocent victimized by circumstance. From this angle, Robespierre’s historically attested introversion became not vicious coldness but demure reticence.[78] The pacific young man who composed love poems in the countryside of Arras learned to overcome his natural diffidence to advocate for his nation in peril. This rereading introduces an alternative significance to the titular letters. Could Robespierre be reading these missives from his victims’ families out of remorse? Is his stoic expression evidence not of hard-heartedness but quiet resignation? Like the tragic figures of Tudor and Stuart history memorialized in other Intimate Romantic canvases, he is a being of strong will, beset by calamity, facing his grievous situation with calm sadness.

While Fisk effeminizes Robespierre, another woman haunts the scene by her absence: Éléonore Duplay (1768–1832). Éléonore was the daughter of Parisian carpenter and ardent Jacobin Maurice Duplay, who rented out a room in his home to Robespierre during the latter’s tenure in the National Convention legislature.[79] Rumors circulated during the Revolution and ever after that Éléonore was the Incorruptible’s “mistress, intended, or common-law wife.”[80] Fisk implies such a relationship via tiny clues hidden throughout the image. First, the foundational choice to set the painting inside Robespierre’s room at the Duplay home evokes the possible liaison. Second, Éléonore was herself a painter who studied at a studio for young female artists run by Jean-Baptiste Regnault (1754–1829) in the Musée du Louvre.[81] Could the painting of a guillotine mounted on an easel be hers? What about the landscape, the still life, or either of the silhouettes hanging on the back wall? Each of these paintings is as ambiguous and potentially polysemic as the painting they appear in, refracting and focusing Fisk’s own elusiveness. Could all of the little trinkets that litter the scene be Éléonore’s doing, thoughtful tokens to brighten the room of her beloved? Did her hands place the shell on the windowsill, or the blue vase on the desk? Do these objects bear the invisible imprint of her touch, caring for the Incorruptible? The obvious question is whether any of the room’s many, many flowers came from her—or, alternatively, are they gifts Robespierre plans to give to her. With that possibility in mind, decoding the flowers that can be identified by type becomes imperative.

The first flower in this painting, the azalea, possessed a highly ambiguous signification in Victorian floriography. In Flora’s Lexicon: An Interpretation of the Language and Sentiment of Flowers (1855), Catharine Harbeson Waterman observed that the “azalea, with large and rich scarlet flowers,” represented romance.[82] Christian Parlor Magazine (1845) similarly asserted that “the splendor of its flowers has been thought sufficient cause to render the Azalea a suitable emblem of Romance.”[83] However, The Hand-Book of the Language and Sentiment of Flowers (1850), The Illustrated Language of Flowers (1856), and The Language of Flowers: An Alphabet of Floral Emblems (1858) all associated the azalea with temperance.[84]

These two elements, romance and temperance, exist in balanced tension in Fisk’s depiction of Robespierre. On the one hand, temperance was a virtue conventionally associated with the Incorruptible. While other revolutionary leaders like Danton or Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau (1749–91), earned historical reputations as hard-drinking womanizers who financed their bodily indulgences through graft, Robespierre was known for his austere, almost ascetic personal life. Unlike many of his colleagues, Robespierre rarely dined out; he famously kept to the Duplays’s home on evenings when he was not needed at the National Convention or the Jacobin Club.[85] Fisk reconciles that Robespierre—a revolutionary homebody working alone in a humble, even shabby rented room above a carpentry shop—with a putative amorous Robespierre through deft allusions to Éléonore. The artist speaks through the language of flowers to insist his subject was simultaneously abstemious and affectionate.

However, the nature of the azalea complicates this message yet further. The azalea is highly poisonous, yet another visual oracle foreshadowing Robespierre’s death on the guillotine, which will bring a tragic end to his affair with Éléonore. Someday Citoyenne Duplay will be like Hunt’s bereaved heroine in Isabella and the Pot of Basil (fig. 10), similarly weeping over her loved one’s decapitated head. The azalea also gestures again toward Robespierre’s bloody acts, the violence he was willing to mete out to protect his revered patrie (fatherland). If the toxic azalea, blending fatality and love, reminds the viewer of Robespierre’s guilt, it also reminds them that he did what he did out of self-annihilating devotion.

The other identifiable plant in the painting, the sweet pea, has a comparably cryptic meaning. The Language of Flowers: Being a Lexicon of the Sentiments Assigned to Flowers, Plants, Fruits, and Roots (1849) and The Hand-Book of the Language and Sentiment of Flowers linked the sweet pea to “delicate pleasure.”[86] The Illustrated Language of Flowers and The Language of Flowers: An Alphabet of Floral Emblems, on the other hand, connected it to “departure.”[87] The Ladies’ Hand-Book of the Language of Flowers (1844) listed both associations.[88] Like the azalea, then, the sweet pea’s dual signification hinted toward both love and loss.

These floral references conjure a relationship as equivocal as they are. By withholding further explanation, Fisk leaves it to the audience to guess at Maximilien and Éléonore’s connection. Was there one at all? Are all of these visual hints of a lover for Robespierre mere red herrings? The moral valence of the relationship, if it exists, is similarly unclear. Like the provocatively posed letters, the summoning of the spectral Éléonore could underline Robespierre’s potential for sexual predation. Fisk certainly leaves open the possibility that Robespierre is a venal cad who seduced his unwitting host’s vulnerable daughter. However, the painting also holds out the prospect of the idealized companionate alternative. Robespierre has chosen not to live in the luxury his power could buy him. Instead, in the words of the writer for The Spectator, he “affects a character for self-denial by living in a garret, and for purity by surrounding himself with flowers.”[89] He resides in a family setting amid an upright, hardworking, clean-living, adoptive clan. The tender little cares lavished on his room readily point to a deep and mutual passion between him and Éléonore. By casting Robespierre in the conjectural role of sentimental lover, Fisk domesticates him. The ghost of Éléonore humanizes the Incorruptible, giving him interiority and noble feelings. He begins to appear not as a bloodstained tyrant but as a model Victorian man, his moral uprightness ensured by the cozy hearth and adoring woman who sustain him. Victorian thinking held that romantic love, a stable home, and family life tamed man’s vicious impulses and made him fit to participate in public life. Fisk’s implied Éléonore does not just make Robespierre sympathetic; she makes him potentially virtuous.

Unraveling Robespierre Receives Letters

With all of its conflicting messages, some contemporary reviewers had a hard time reading this painting. The Athenaeum for one knew that something was decidedly off. Beholding the odd, flower-strewn scene, the critic ruled that Fisk had utterly failed to capture the true Robespierre: “Mr. W. H. Fisk’s Robespierre receives letters from Friends of his Victims, threatening him with Assassination (353) is grim and absurd. If Mr. Fisk will paint the Incorruptible, let him first take a peep at a genuine likeness. There is a very good one in the great Gallery of Versailles.”[90] The canvas’s absurdity hinged on its act of misrecognition. In the writer’s opinion, Fisk had not understood Robespierre, had not conveyed his historical reality. The critic balked at the depiction of a domestic, whimsical Robespierre, a depiction which in his mind could have no historical merit. As a result of this foundational misrepresentation, the entire painting was preposterous.

Though Fisk surely would have resented such an attack on his work, the significative opacity The Athenaeum condemned was clearly the painting’s intended effect. The mercurial mishmash of conflicting messages I have reviewed to this point structured the very DNA of the image. But why? Why did Fisk create such an unrecognizable Robespierre? And why does it matter that this painting is so resistant to a singular interpretation? I contend that Fisk’s choice to avoid passing a definitive judgment on his subject represented a conscious move away from the vehement anti-Jacobinism of the British tradition enshrined by Burke. Instead, Fisk attempted to inaugurate a softening of hostility toward the revolutionaries. The genre elements grafted onto this painting sever the revolutionary past from the political debates that had dominated its reception in Victorian Britain to that point. By approaching Robespierre through a genre lens, Fisk offered not a value statement on the Incorruptible but a normative statement on the relationship between art, history, and the present. He suggested that his audience should appreciate even tragedy on aesthetic terms.

This rubric permits a rereading of Robespierre that in turn opens up a novel understanding of the French Revolution. Foregrounding the aesthetic, even romantic, appeal of the Incorruptible’s story disconnects him and the Terror he embodies from the problems of faction and ideology. Suddenly, the Revolution is not about the pursuit of radical political transformation; it is about the personal, emotional experience of its actors. No longer a moment of societal destruction, it is simply the showcase of extreme, and therefore interesting, human feeling. Fisk displaces the French Revolution from its position as modernity’s founding catastrophe and the origin of nineteenth-century social upheaval. Rather than Victorian Europe’s central problem in need of a solution, it becomes an intriguing curiosity. Fisk extracts the Revolution from its pervasive political framing, permitting it to be retrospectively enjoyed as a stage for high human drama.

Fisk’s aspirations to aestheticize the Revolution come into even sharper relief when Robespierre Receives Letters is juxtaposed with a third painting by the artist depicting the eventful summer of 1794: Awaiting Publication of “Le Moniteur” for News of the Arrest of Robespierre (fig. 11). Displayed at the Royal Academy in 1866, Awaiting Publication of “Le Moniteur” portrays a grim crowd crammed into a French newsagent’s office, clamoring for the paper which would detail the Thermidorian coup that toppled Robespierre. As in Robespierre Receives Letters, Fisk repudiates the obvious approach to his subject matter, in this case Thermidor. He does not reproduce the shocking confrontation between Robespierre and his enemies in the legislature, nor the nighttime siege of the Hôtel de Ville, nor even the Incorruptible’s final execution, all popular subjects in French academic art in the 1860s and ’70s. Indeed, Fisk ignores the plot’s protagonists entirely, focusing instead on passive Everymen who experience the event secondhand. Like Robespierre Receives Letters, Awaiting Publication of “Le Moniteur” declines to take a clear side. Are the stoic citizens who populate the scene hoping Robespierre will triumph or fall? Does the tricolor cockade of the bewigged man in the foreground indicate his Jacobin allegiance or merely his generic patriotism? It is impossible to know for certain. Moreover, Fisk festoons the image with whimsical flowers, ribbons, and feathers that hark directly back to Robespierre Receives Letters. Indeed, Awaiting Publication of “Le Moniteur” shares Fisk’s earlier commitment to unexpected settings, political evasion, and fanciful beauty.

This artistic sensibility performs subtle political work while it simultaneously decries politics as a category. By rejecting an ideologically driven posture vis-à-vis the Revolution, Fisk defuses a cultural bomb. Unlike the stridently militant portraits of Robespierre produced by French artists in the same decade, Robespierre Receives Letters does not seek to reignite revolutionary tensions; it seeks to stifle them.[91] It thus contributes to a wider project in British art of dampening the public’s political engagement. By valorizing beauty at the expense of message, Victorian artists constructed a national identity that was triumphantly apolitical. They believed a common admiration for visual grace could unite the nation and extinguish roiling dissent. Indeed, the (willfully perceived) lack of revolutionary uproar became a hallmark of Britishness in conservative eyes. By choosing to thus ignore the activism of working-class, female, and colonized leaders vocally vindicating their rights, conservative thinkers effectively marginalized that activism. Consequently, Fisk’s embrace of Robespierre as dramatic subject was part and parcel of neutering revolutionary action.

Conclusion

After their exhibition at the Royal Academy, both The Old Noblesse in the Conciergerie and Robespierre Receives Letters were purchased by Mr. Albert Grant, who immediately attempted to sell them in November 1863.[92] He was evidently unable to unload the latter, as he put it up for auction again in April 1877, when it sold for forty-eight pounds, six shillings.[93] After disappearing from the historical record for over a century, Robespierre Receives Letters came up for auction once more in 2009 at the Lécuyer Gallery in Paris, where it was purchased by the Musée de la Révolution Française in Vizille in the Isère department, an institution dedicated to celebrating France’s revolutionary heritage.[94] Since its reappearance, the painting has become an object of fascination in the corners of the internet devoted to Revolution fandom; Rodama: A Blog of 18th Century & Revolutionary French Trivia and importanttomadeleine both display notable affection for it.[95] Rodama calls it “glorious,” and importanttomadeleine uses it as the blog’s cover image. When the user needsmoreresearch posted a photo of Robespierre Receives Letters to Tumblr, it received 1,192 notes.[96] Anthony Pascal of the blog Les Dentus even visited the site of the Duplays’s home to determine the accuracy of the painting’s floor plan.[97] In a more serious example, the Université Paris Diderot featured Robespierre Receives Letters prominently in its advertising for the 2016–17 seminar series “Imaginaires de la Révolution Française de 1789 à Aujourd’hui” (Imaginaries of the French Revolution from 1789 to the present).[98]

What does it mean that this painting has been embraced by online fans and scholarly institutions alike? First and foremost, it demonstrates the canvas’s potential to be read sympathetically. Even today, far removed from Fisk’s own aesthetic milieu, audiences readily intuit that this image does not straightforwardly condemn Robespierre. Though not fluent in the visual language of the 1860s, contemporary viewers arguably sense that this picture elevates its subject from simple despot to true original. It awards him a private and inner life; it revels in his body, clothing, and décor. It cannot detest Robespierre, because it is too fascinated by him.

Fisk came to praise Robespierre but also to bury him. By eschewing the stark black-and-white partisanship that had dominated depictions of Robespierre up to that moment, the artist effectively neutralized the dead man’s disruptive potential. On Fisk’s canvas, the Incorruptible ceased to be the blood-soaked tyrant of Carlyle’s nightmares and consequently also ceased to be the foundational architect of modern left-right political divisions. By refusing to paint him as a simple villain, Fisk took away his significance. This eccentric, feminine Robespierre embodied a Revolution devoid of contemporary resonance. Politically incomprehensible, he could only be appreciated on an aesthetic basis, as the incarnation of outsized human passions and a distant history stranger than fiction.

By downplaying Robespierre’s traditional role as potent ideological symbol, Fisk attempted to depoliticize British art and the public sphere at large. This act of de-escalation supported a broader cultural project of short-circuiting radical protest through the discursive production of an imagined prepolitical—indeed, apolitical—Britishness. Painters such as Fisk honed a distinct Victorian style that valued beauty, emotion, and excess. They conceptualized British identity in these terms, as something aesthetically rather than politically defined. Britons were united not by shared ideological struggles but by common sensibilities—soft, homely, nonthreatening sensibilities at that. Thus, paradoxically, Fisk transformed Robespierre—of all people—into a vector of political apathy.

Acknowledgments

My profound thanks to Nancy Rose Marshall, Suzanne Desan, Brandon Bloch, Guiliana Chamedes, and the students of the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s modern European history reading group for their generous and constructive comments on this article. Thanks also to Isabel Taube, Julia Thomas, and the anonymous peer reviewer for their invaluable feedback.

Notes

All translations, unless otherwise noted, are my own.

[1] I have not been able to locate the original painting, so I am using an engraving to illustrate it (see fig. 1). A preparatory study in watercolor was at one time held by the Chris Beetles Gallery in London.

[2] Royal Academy of Arts (Great Britain), The Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts (1863), exh. cat. (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1863), 28.

[3] Kirsty Carpenter, Refugees of the French Revolution: Émigrés in London, 1789–1802 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999); Adriana Craciun, “Citizens of the World: Émigrés, Romantic Cosmopolitanism, and Charlotte Smith,” Nineteenth Century Contexts 29, no. 2–3 (2007): 169–85; Maya Jasanoff, “Revolutionary Exiles: The American Loyalist and French Émigré Diasporas,” in The Age of Revolutions in Global Context, c. 1760–1840, ed. David Armitage and Sanjay Subrahmanyam (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 37–58; and Juliette Reboul, French Emigration to Great Britain in Response to the French Revolution (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillian, 2017).

[4] Margery Weiner, The French Exiles, 1789–1815 (London: Unwin Brothers, 1960), 31–38.

[5] Royal Academy of Arts (Great Britain), Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts (1863), 17.

[6] Robespierre Receives Letters from the Friends of His Victims, Threatening Him with Assassination is the title given in the Royal Academy’s 1863 catalogue and in all contemporary reviews. Robespierre Receiving Dispatches only ever appears as the title on the frame in the Musée de la Révolution Française in Vizille in the Isère department.

[7] J. R. Dinwiddy, “English Radicals and the French Revolution, 1800–1850,” in Radicalism and Reform in Britain, 1750–1850 (London: Bloomsbury, 2003), 207–28.

[8] Linda Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707–1837 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009).

[9] Roland Quinault, “The French Revolution of 1830 and Parliamentary Reform,” History 79, no. 257 (1994): 377–93.

[10] Fabrice Bensimon, “L’Écho de la Révolution française dans la Grande-Bretagne du XIXe siècle (1815–1870),” Annales historiques de la Révolution française, no. 342 (October–December 2005): 13–15.

[11] Michael J. Turner, “Revolutionary Connection: ‘The Incorruptible’ Maximilien Robespierre and the ‘Schoolmaster of Chartism’ Bronterre O’Brien,” The Historian 75, no. 2 (Summer 2013): 237–61.

[12] Roy Strong, Painting the Past: The Victorian Painter and British History (London: Pimlico, 2004), 9, 47. See also Jochen Wierich, “The Domestication of History in American Art: 1848–1876” (PhD diss., College of William and Mary, 1998).

[13] Caroline Arscott, “Sentimentality in Victorian Paintings,” in Art for the People: Culture in the Slums of Late Victorian Britain, ed. Giles Waterford (London: Dulwich Picture Gallery, 1994), 65–82; and Julia Thomas, “Nation and Narration: The Englishness of Victorian Narrative Painting,” in Pictorial Victorians: The Inscription of Values in Word and Image (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2004), 105–24.

[14] Emily Jones, “Constructive Constitutionalism in Conservative and Unionist Political Thought, c. 1885–1914,” English Historical Review 134, no. 567 (April 2019): 334–57; and Bensimon, “L’Écho de la Révolution française dans la Grande-Bretagne,” 2, 9, 13.

[15] Lionel Henry Cust, “Fisk, William Henry,” in Dictionary of National Biography, ed. Leslie Stephen, vol. 19 (New York: Macmillan, 1889), 76; J. B. Manson, Frederick George Stephens and the Pre-Raphaelite Brothers (London: Donald Macbeth, 1920), 2; “Fisk, William Henry,” in Algernon Graves, The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and Their Work from Its Foundation in 1769 to 1904, vol. 3 (London: Henry Graves, 1905), 118–20; Christopher Wright, Catherine Gordon, and Mary Peskett Smith, eds., British and Irish Paintings in Public Collections: An Index of British and Irish Oil Paintings by Artists Born Before 1870 in Public and Institutional Collections in the United Kingdom and Ireland (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006), 340; G. B., “Fisk, William Henry,” in Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon, vol. 40 (Munich: K. G. Saur Verlag, 2004), 498–99; and Henry Ffiske, Fiske Family Papers (Norwich: Fletcher, 1902), 367–71.

[16] Cust, “Fisk, William Henry,” 76.

[17] “Ghiberti: Design for a Mosaic in the Museum (the ‘Kensington Valhalla’),” The Victoria and Albert Museum, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/.

[18] Cust, “Fisk, William Henry,” 76; and “Fisk, William Henry,” 120.

[19] Susan Isaac, “Flayed Penguin: Anatomical Drawings by William Henry Fisk (1827–1884),” Royal College of Surgeons of England, April 21, 2017, https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/.

[20] Cust, “Fisk, William Henry,” 76; Manson, Frederick George Stephens and the Pre-Raphaelite Brothers, 2; and Pamela Geraldine Nunn, “The Mid-Victorian Woman Artist: 1850–1879” (PhD diss., University College London, 1982), 147–48.

[21] “Ghiberti: Design for a Mosaic in the Museum (the ‘Kensington Valhalla’).”

[22] Cust, “Fisk, William Henry,” 76.

[23] Iain McCalman has provocatively suggested that Burke’s attack on the French Revolution was actually inspired by his revulsion toward the Gordon Riots of 1780 in Britain. This interpretation intriguingly flips the usual France/Britain binary, presenting Britain as the country of anarchic mob violence and France as the country which must fear the contamination of that violence. See Iain McCalman, “Mad Lord George and Madame La Motte: Riot and Sexuality in the Genesis of Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France,” Journal of British Studies 35, no. 3 (July 1996): 343–67.

[24] Randolph A. Miller, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Robespierre: Toward a Reconstruction of Socialist Historiographical Assumptions Before Marx” (master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, 2009).

[25] Thomas Carlyle, The French Revolution: A History, vol. 3 (Leipzig: Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1851), 313.

[26] H. M. Leicester Jr. has argued convincingly that there are actually two Robespierres in Carlyle’s writing: Robespierre the historical individual, and Robespierre the poetic avatar of anarchy. H. M. Leicester Jr., “The Dialectic of Romantic Historiography: Prospect and Retrospect in The French Revolution,” Victorian Studies 15, no. 1 (September 1971): 5–17.

[27] Royal Academy of Arts (Great Britain), Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts (1863), 17.

[28] “Fine Arts. The Royal Academy. Third Notice,” The Spectator, May 23, 1863, 2036.

[29] “Royal Academy,” Morning Post, May 14, 1863, 3.

[30] “In dem andern Bild ist ihm Robespierre trefflich gelungen, und er hat dessen Physiognomie den verächtlichen, die Menschheit wegwerfenden Zug glücklich beizumischen verstanden.” “Die englische Kunst. V,” Allgemeine Zeitung, October 8, 1864, 4585. Thanks to Dr. Chad Gibbs of the College of Charleston for this translation.

[31] “The Royal Academy,” The Art Journal, 1839–1912, June 1863, 107. Some of this passage was reprinted in “The Old Noblesse in the Conciergerie, from the Picture in the Possession of the Publishers,” The Art Journal, vol. 8 (London: Virtue, 1879): 140.

[32] According to Helen Margaret Sutherland, the Victorian era “was a period in which painting was marked by a very strong narrative drive. . . . This technique of reading a painting (from the viewer’s point of view) or constructing it (from the artist’s) became the accepted, indeed, almost the only way of looking at paintings.” This process of constructing and reading a painting’s narrative is clearly at work in Fisk’s canvas. Helen Margaret Sutherland, “The Function of Fantasy in Victorian Literature, Art and Architecture” (PhD diss., University of Glasgow, 1999), 30.

[33] For the most recent monograph on the Festival of the Supreme Being, see Jonathan Smyth, Robespierre and the Festival of the Supreme Being: The Search for a Republican Morality (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2016).

[34] G. H. Lewis, The Life of Maximilien Robespierre (London: Chapman and Hall, 1849), 341, 380; and John Hardman, Robespierre (New York: Routledge, 2014).

[35] My profound thanks to Dr. Kai Battenberg of the RIKEN CSRS Plant Symbiosis Research Team in Yokohama, Japan, for identifying these specimens.

[36] Bronisław Baczko, Ending the Terror: The French Revolution after Robespierre, trans. Michel Petheram (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 28.

[37] Fisk may well have read G. H. Lewis’s description of the coup’s genesis in the Festival. See Lewis, Life of Maximilien Robespierre, 344.

[38] “Fine Arts. The Royal Academy. Third Notice,” 2036.

[39] “Fine Arts,” The Examiner, July 18, 1863, 456.

[40] On the long life of this trope, see Linda M. Shires, “Of Maenads, Mothers, and Feminized Males: Victorian Readings of the French Revolution,” in Rewriting the Victorians: Theory, History, and the Politics of Gender, ed. Linda M. Shires, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2012), 147–65.

[41] Ernest Chesneau, “The Pre-Raphaelites,” in The English School of Painting, trans. Lucy Etherington, 4th ed. (London: Cassell, 1885), 199.

[42] Chesneau, “Pre-Raphaelites,” 205.

[43] “Fisk, William Henry,” 120.

[44] Chesneau, “Pre-Raphaelites,” 184, 186–87.

[45] I have been unable to locate Fisk’s Last Evening of Our Lord at Nazareth.

[46] Landow errs in calling Fisk an American. George P. Landow, “‘Your Good Influence on Me’: The Correspondence of John Ruskin and William Holman Hunt II,” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library of Manchester, no. 59 (1976–77): 367–96.

[47] William Holman Hunt to John Ruskin, 1884, quoted in Landow, “‘Your Good Influence on Me,’” 387.

[48] E. C., “Some Great English Painters,” Cassell’s Family Magazine (London: Cassell, 1885), 505.

[49] Manson, Frederick George Stephens and the Pre-Raphaelite Brothers, 2.

[50] Stefan van den Bossche, Zuiver en ontroerend beweegloos. Prerafaëlitische sporen in de Belgische kunst en literatuur (Antwerp: Garant, 2016), 81.

[51] “The Royal Academy,” The Art Journal, 1839–1912, June 1864, 159.

[52] “The Royal Academy,” The Art Journal, 1839–1912, June 1863, 107.

[53] “The Old Noblesse in the Conciergerie, from the Picture in the Possession of the Publishers,” 140.

[54] “Fine Arts,” 2036.

[55] Gavin Budge, “The Hallucination of the Real: Pre-Raphaelite Vision, Democracy and Masculinity,” in Romanticism, Medicine and the Supernatural: Transcendent Vision and Bodily Spectres, 1789–1852 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 176.

[56] “Royal Academy,” 3.

[57] William Michael Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti: His Family Letters; With a Memoir by William Michael Rossetti, vol. 1 (London: Ellis and Elvey, 1895), no. 203, quoted in Allen Staley, “Pre-Raphaelites in the 1860s I: Rossetti,” British Art Journal 4, no. 3 (Autumn 2003): 13.

[58] Sutherland, “Function of Fantasy in Victorian Literature, Art and Architecture,” 244. For further analysis of The Secret, see Mary Cowling, Victorian Figurative Painting: Domestic Life and the Contemporary Social Scene (London: Andreas Papadakis, 2000), 36.

[59] “Royal Academy,” 3.

[60] Sutherland, “Function of Fantasy in Victorian Literature, Art and Architecture,” 44.

[61] “Royal Academy,” 3.

[62] For detail in art as coded feminine, see Naomi Schor, Reading in Detail: Aesthetics and the Feminine (New York: Methuen, 1987).

[63] On the cult of domesticity, see Bonnie Smith, Ladies of the Leisure Class: The Bourgeoises of Northern France in the Nineteenth Century (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981); Mary Poovey, Uneven Developments: The Ideological Work of Gender in Mid-Victorian England (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988); Judith Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992); and Erika Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure: Women in the Making of London’s West End (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000).

[64] Dena Goodman, “The Secrétaire and the Integration of the Eighteenth-Century Self,” in Furnishing the Eighteenth Century: What Furniture Can Tell Us about the European and American Past, ed. Dena Goodman and Kathryn Norberg (New York: Routledge, 2007), 188.

[65] On Victorian concerns about masturbation, see Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, vol. 1, An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage Books, 1980); Emma L. Rees, “Narrating the Victorian Vagina: Charlotte Brontë and the Masturbating Woman,” in The Female Body in Medicine and Literature, ed. Andrew Mangham and Greta Depledge (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2011), 119–34; and April R. Haynes, Riotous Flesh: Women, Physiology, and the Solitary Vice in Nineteenth-Century America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

[66] Julia Douthwaite, The Frankenstein of 1790 and Other Lost Chapters from Revolutionary France (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 273.

[67] Jean Marie Goulemot, Forbidden Texts: Erotic Literature and Its Readers in Eighteenth-Century France, trans. James Simpson (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995), 38.

[68] Mary Ellen Snodgrass, Encyclopedia of Gothic Literature (New York: Facts on File, 2005), s.v. “sadism.”

[69] Louis Ange Pitou, “La Queue, la tête, et le front de Robespierre” / “The Tail, Head, and Forehead of Robespierre,” in Antoine de Baecque, Glory and Terror: Seven Deaths under the French Revolution, trans. Charlotte Mandell (New York: Routledge, 2003), 163. Mandell cites the title of the poem in both French and English but provides only the poem’s English translation.

[70] Jean-Baptiste-Moïse Jollivet, Coupons-lui la queue (Paris: Amis de la Vérité, 1794); Coupez-moi la Queue, ou la Chanson des Carmagnoles [Paris, 1794–95]; Jean-Claude-Hippolyte Méhée de la Touche, Rendez-moi ma queue, ou lettre a Sartine Thuriot, sur une violation de la liberté de la presse et des droits de l’homme (Paris, 1795); Renvoyez-moi ma queue, ou Lettre de Robespierre à la Convention nationale (Paris: Guffroi, 1794); La Tête à la queue, ou Première lettre de Robespierre, à ses continuateurs (Paris: Guffroy, [1794–95]); Lamberti, Les Parties honteuses de Robespierre, restées aux Jacobins [Paris, 1794–95]; and Testament de I. M. Robespierre, trouvé à la maison commune (Paris: Journal du Soir, 1794).

[71] “Le principe fondamental du gouvernement démocratique ou populaire, c’est-à-dire le ressort essential qui le soutient et qui le fait mouvoir. . . . Le ressort du gouvernement populaire en révolution est à la fois la vertu et la terreur: la vertu, sans laquelle la terreur est funeste; la terreur, sans laquelle la vertu est impuissant. La terreur n’est autre chose que la justice prompte, sévère, inflexible.” Maximilien Robespierre, “Rapport sur les principes de morale politique,” 1794, in Discours par Maximilien Robespierre: 17 avril 1792–27 juillet 1794, ed. Charles Vellay (Kindle, 2011), loc. 2292.

[72] Joan Wallach Scott, “French Feminists and the Rights of ‘Man’: Olympe de Gouges’s Declarations,” History Workshop, no. 28 (1989): 1; and Joan Wallach Scott, Only Paradoxes to Offer: French Feminists and the Rights of Man (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 19–56.

[73] Denise Riley, “Does a Sex Have a History? ‘Women’ and Feminism,” New Formations, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 39–40.

[74] Strong, Painting the Past, 9, 47.

[75] Strong, Painting the Past, 62.

[76] Strong, Painting the Past, 144.

[77] Strong, Painting the Past, 130.

[78] On Robespierre’s personal psychology and early life, see Ruth Scurr, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006); and Peter McPhee, Robespierre: A Revolutionary Life (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012).

[79] Susan Siegfried, “The Visual Culture of Fashion and the Classical Ideal in Post-Revolutionary France,” The Art Bulletin 97, no. 1 (2015): 88–89.

[80] Siegfried, “Visual Culture of Fashion,” 89.

[81] Siegfried, “Visual Culture of Fashion,” 88.

[82] Catharine Harbeson Waterman, Flora’s Lexicon: An Interpretation of the Language and Sentiment of Flowers (Boston: Philips, Sampson, 1855), 32.

[83] “The Pink Azalea, or American Woodbine,” Christian Parlor Magazine, March 1845, 340.

[84] Robert Tyas, The Hand-Book of the Language and Sentiment of Flowers (London: Houlston and Stoneman, 1850), 14; L. Burke, ed., The Illustrated Language of Flowers (London: G. Routledge, 1856), 9; and The Language of Flowers: An Alphabet of Floral Emblems (London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1858), 9.

[85] Marissa Linton and Mette Harder, “‘Come and Dine’: The Dangers of Conspicuous Consumption in French Revolutionary Politics, 1789–95,” European History Quarterly 45, no. 4 (2015): 625.

[86] The Language of Flowers: Being a Lexicon of the Sentiments Assigned to Flowers, Plants, Fruits, and Roots (Edinburgh: Paton and Ritchie, 1849), 27; and Tyas, Hand-Book of the Language and Sentiment of Flowers, 42.

[87] Burke, Illustrated Language of Flowers, 46; and The Language of Flowers: An Alphabet of Floral Emblems, 14.

[88] Lucy Hooper, The Ladies’ Hand-Book of the Language of Flowers (London: H. G. Clarke, 1844), 34.

[89] “Fine Arts,” 2036.

[90] “Royal Academy,” The Athenaeum, May 16, 1863, 656.

[91] On the French republican portraits of Robespierre produced during the nineteenth century, see Antoinette Ehrard, “Un sphinx moderne? De quelques images de Robespierre au 19e siècle,” in Images de Robespierre, ed. Jean Ehrard (Naples: Vivarium, 1996), 263–97.

[92] “Advertisement,” The Athenaeum, October 24, 1863, 514; “Advertisement,” The Athenaeum, October 31, 1863, 555; “The Choice Collection of Modern Pictures and Drawings of A. Grant, Esq.,” Morning Post, November 2, 1863, 8; and “Picture Sales,” The Art Journal, 1839–1912, January 1864, 18.

[93] “The Kensington House Collection,” The Architect: A Weekly Illustrated Journal of Art, Civil Engineering, and Building, May 5, 1877, 295.

[94] Didier Rykner, “Acquisitions du Musée de la Révolution Française à Vizille: Le XIXe siècle,” La Tribune de l’Art, August 10, 2010, https://www.latribunedelart.com/ [login required].

[95] Rodama1789, “Robespierre: The View from Victorian England,” Rodama: A Blog of 18th Century & Revolutionary French Trivia, August 25, 2013, http://rodama1789.blogspot.com/; and importanttomadeleine, “18th Century: Robespierre Receiving Letters from Friends of His Victims with Assassination Threats, by William Henry Fisk,” importanttomadeleine, June 24, 2014, https://importanttomadeleine.blogspot.com/.

[96] needsmoreresearch, “Robespierre sitting around in his feathery hat and checking his hate-mail. William Henry Fisk (1827–1884),” Tumblr, February 27, 2015, https://needsmoreresearch.tumblr.com/.

[97] Anthony Pascal, “J’ai visité la chambre de Robespierre,” Les Dentus, April 21, 2014, http://les-dentus.blogspot.com/.

[98] “Imaginaires de la Révolution française de 1789 à aujourd’hui,” Université Paris Diderot, accessed April 14, 2020, http://seebacher.lac.univ-paris-diderot.fr/.