Monet / Mitchell: Painting the French Landscape

Reviewed by David O’BrienDavid O’Brien

Professor of Art History

University of Illinois

Email the author: obrien1[at]illinois.edu

Citation: David O’Brien, exhibition review of Monet / Mitchell: Painting the French Landscape, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 2 (Autumn 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.2.20.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Monet / Mitchell: Painting the French Landscape

Saint Louis Art Museum

March 25–June 25, 2003

Catalogue:

Simon Kelly, ed.,

Monet / Mitchell: Painting the French Landscape.

Saint Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum, 2023.

96 pp.; 62 color illus.; bibliography; notes; index.

$50.00 (hardcover)

ISBN: 9783777440927

The idea behind this exhibition—a comparison of works by Claude Monet (1840–1926) and Joan Mitchell (1925–92)—is irresistible, at least for those happy few who still enjoy immersing themselves in the formalist appreciation of canonical modernism. An exhibition with the same theme was held by the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris from October 2022 to February 2023, but it was a significantly larger show that included Mitchell’s pastels and drawings as well as more paintings. The exhibition under review here (fig. 1), organized by Simon Kelly, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Saint Louis Art Museum (SLAM), displays twelve mid- to large-scale canvases by Monet, all from between the years 1914 and 1926, and twelve large canvases by Mitchell, all from the period from 1976 to 1992, except for one from 1971. Thus, it is the late Monet of the Japanese bridges, waterlilies, and other pond flora painted in Giverny, and the late Mitchell of wide, gestural brushstrokes and massive, abstract polyptychs and single canvases, painted in Vétheuil, often responding indirectly to the landscape there. The exhibition is accompanied by a beautifully illustrated catalogue with three essays: a long one by Kelly that compellingly compares the work of the two artists, a shorter article by Marianne Mathieu with new research on Michel Monet’s (1878–1966) bequest to the Musée Marmottan, and a short account of Mitchell’s life and work in Vétheuil by Suzanne Pagé.

The comparison between Monet and Mitchell suggests itself because of their art’s obvious formal similarities and the proximity of the places in which they lived and worked in the final decades of their careers. Mitchell often made the comparison herself, at least initially after moving to France, and it was used by galleries and museums to market her work into the 1970s. Mitchell eventually began to downplay her connections to Monet, even mispronouncing and misspelling his name. As Kelly summarizes it, “Mitchell’s attitude to Monet during her time at Vétheuil evolved from ‘adoration’ in the early 1970s, to a growing need to distance herself from him by about 1980, to an outright disavowal of any influence from the French painter by the end of her career” (61). Her purchase of a home and studio in Vétheuil in 1967 had made the comparison with Monet inevitable: Monet had lived in Vétheuil between 1878 and 1881, Mitchell’s house was located on avenue Claude Monet, and her work was inspired by the landscape that surrounded her there, if not as directly as was Monet’s. Mitchell had every reason to be anxious regarding his perceived influence on her practice, as her own achievements might be subordinated to his. The catalogue makes clear that there is still a danger of overreading his influence and displacing a woman’s genius by explaining it as the result of a man’s.

All of this is true, but the burden Mitchell may have felt in being compared to Monet can be misconstrued. First of all, the question of influence is not simply about how Monet affected Mitchell. One might be excused in framing the question this way, as Mitchell was born less than a year before Monet died, thus rendering absurd the question of what Monet thought of her work. Focusing only on Monet’s influence, however, leaves aside an equally interesting question: how has Mitchell’s work influenced our perception of Monet’s? There is a scene in David Lodge’s novel Small World (1984) that addresses a similar situation. Persse McGariggle, a junior professor at a small Irish university, has written a dissertation about the influence of Shakespeare on T. S. Eliot, but to befuddle a tiresome senior academic he meets at a conference in England, he reverses the thesis and tells him that his research is about the influence of T. S. Eliot on Shakespeare. “That sounds very Irish, if I may say so,” replies his colleague. But later, when McGarrigle confesses his prank to a mysterious and brilliant scholar he is courting, she observes, correctly, that “it’s a more interesting idea, actually.” Similarly, this exhibition provokes the question of how our post-Mitchell, post-abex, post-modernist eyes see Monet.

Secondly, when Mitchell began her career, Monet’s late work was still challenging, even baffling, for the general public, and it was not firmly part of the academic canon. As Mathieu recounts in her essay, when Monet’s Water Lilies murals in the basement of the Orangerie first opened to the public in 1927 they were “roundly criticized” (74), and visitors to these rooms were few for decades. Monet’s dealers found the more gestural and abstract paintings, which make up the majority of works in this exhibition, too radical, and they had left them in the artist’s studio. Monet’s late work remained little known and “entered into the purgatory of art history” (74). The reception of the late work continued to be largely negative into the 1950s, though it enjoyed renewed prestige in avant-garde circles and particularly with abstract expressionists.[1] Then the market picked up. The Museum of Modern Art acquired its first Water Lilies in 1955; Clement Greenberg’s “The Later Monet” appeared in 1957.[2] In the early 1970s, the bequest of Michel Monet to the Musée Marmottan Monet, filled with gestural, abstract, possibly unfinished works, began to go on display and slowly gained the traction that it still enjoys today.

Mitchell received her BFA in 1947 and her MFA in 1950, both from the Art Institute of Chicago. Leo Castelli financed and curated the famous “Ninth Street Show,” which included Mitchell, in 1951. Thus, when she began her career, Monet’s late work could still be considered unconventional and experimental. One could hardly imagine its regular inclusion in the blockbuster shows of the 1980s. Her own apparently changing attitude towards Monet needs to be seen against this backdrop: by the 1980s, comparison to Monet not only raised issues of influence, but also connected her to banal mass-cultural spectacles.

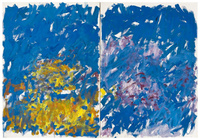

Finally, the similarities between Monet and Mitchell—great as they are—can be overdrawn. Monet made his reputation with his figurative landscapes and usually painted en plein air; Mitchell produced abstract works in her studio, often at night. Monet never dripped or spattered paint; Mitchell did. The exhibition under review negotiates these complexities remarkably well by not forcing the comparison. Works are generously spaced, and walls often emphasize the work of one or the other artist (fig. 2). The themes announced by wall texts in three of the five rooms foregrounded subject matter (“Gardens and Trees,” “Gardens and Flowers,” “Fields, Water, and Reflections” [fig. 3]), while those in the two others were formal (“Color and Abstraction” [fig. 4] and “Experiments in Pictorial Space”). The attention to subject matter may skew things toward Monet, encouraging viewers to look for illusions, but Mitchell’s work more than holds its own. Indeed, her tendency to push formal experimentation to its breaking point, where one is not sure if effects are intentional, makes Monet’s own explorations seem highly structured. Mitchell’s work is louder, so to speak, than Monet’s: the contrasts of tone and hue are greater, the canvases are generally larger, the strokes are bigger and applied more forcefully. For this viewer, Mitchell’s work dominated the show, in part because its complex formal logic demanded more attention, but also because some of the Monets in the show were chosen not because of their inherent qualities, but for the comparisons they offer with the Mitchells.

One of the most intriguing canvases in the show was Mitchell’s Minnesota from 1980 (fig. 5), an enormous (260.4 x 621.7 cm) four-panel polyptych—so big, interestingly, that Mitchell would not have been able to put all the panels together in her studio. The individual panels are sometimes joined by strokes that cross from one canvas to another and by forms that do the same, such as those, for example, created by the dark, descending strokes at the bottom of the leftmost panels, or the purple strokes at the bottom of the center two. At the same time, transitions between panels can be jarringly abrupt, as is the join between the two panels on the right. There is clearly some organization and unity. For example, the agitated, dense, and interwoven strokes of the outermost panels in some sense frame the inner two and throw into relief the large areas of thinly applied, washy, lemon-yellow paint. The darker tones on the sides similarly set off the lighter central area. And the mood of the center panels—especially the one on the right—appears serene and the space deep precisely because of the contrast with the outer panels. At the same time, no consistent system is used to join the panels—sometimes the handling and color scheme crosses the divide between canvases and sometimes it does not. The painting fascinates in part because it experiments with so many formal effects but refuses any conclusions regarding the system or logic that governs the whole.

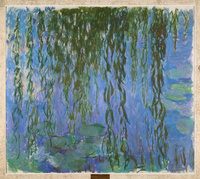

Many of the works by Monet in the show seem selected for their ability to stand next to Mitchell—that is, for their forceful handling and rich color schemes. While some of these are especially bold versions of familiar Giverny themes or modes (e.g., Water Lilies, [fig. 6]), the raw, spontaneous character of others raises the question of whether they are finished (e.g., Water Lilies with Weeping Willow Branches, [fig. 7]). It is salutary to remember that Pierre Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) and Monet did not initially regard the sketches they made in 1869 at La Grenouillère as finished and only later viewed them in this way, and yet they have become canonical works of impressionism. Perhaps Monet arrived at a similar realization in Giverny. Nonetheless, some of the works seem unfinished by any standard. The exhibition includes two long panels depicting garlands of wisteria from ca. 1919–20 (figs. 8, 9). Much of the paint that was on the bottom of both canvases has been scraped away, leaving formless patches of purple, blue, and pink, through which the white primed canvas sometimes shows. These paintings may have been intended to hang in the pavilion Monet once envisioned for his work beside the Musée Rodin in Paris, above panels of water lily paintings, including SLAM’s very own from ca. 1915–26 (fig. 10), which is displayed on the opposite wall of the same gallery. They are thus fascinating works and provide valuable insight into Monet’s multi-canvas projects and late-career ambitions, but they are probably not complete works.

One painting by Monet, the Water Lilies from ca. 1917–19 (fig. 11), is particularly challenging in this regard. Much of the canvas is bare, and the forms of willows, lilies, and other plants have only just been sketched in using an unusually varied, even disjunctive palette that includes a few dark tones approaching black. Kelly chose to hang the painting so that it is turned 180° from the way it appears in the catalogue raisonné.[3] I have difficulty deciding which way it should be oriented. The inclusion of the painting and its hanging are daring: so many curators obsess over landing acknowledged masterpieces to the exclusion of all else. The painting forces viewers to consider what counted as finished in Giverny and how little we know about Monet’s own attitude towards such canvases. Still, it does not invite the same level of aesthetic engagement, nor does it offer the same rewards as clearly finished paintings by both Monet and Mitchell.

While there were a few works that must have tested the mettle of even Monet’s most ardent admirers, there were many that provided exactly what one expects. The Saint Louis Water Lilies (see fig. 10) was intended by Monet as the centerpiece of a triptych that was broken up and sold in 1956. The Fondation Louis Vuitton show reunited it with the other panels, now in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and the Cleveland Museum of Art, but the value of the works to their respective collections made this feat impossible to repeat. It stands very well on its own and offers an example of the carefully worked up handling and finish Monet could bring to these canvases. Other Monets in the exhibition pursue very different effects. There are numerous paintings that employ a jarring color scheme or chromatic range, that feature unusually thick, gestural, dense handling, or that leave parts of the canvas unpainted—works like Weeping Willow from ca. 1921–22 (fig. 12) and The Japanese Bridge from ca. 1918–24 (fig. 13). One might wonder to what extent they are affected by Monet’s cataracts or whether they are finished, but they hardly shock today. On the contrary, the best of them provoke a formal engagement on the same level as Mitchell’s work.

The comparison with Mitchell accentuates Monet’s adherence to certain procedures: with Monet, attention is often distributed evenly across the entire canvas (Greenberg’s “alloverness”), a geometric structure undergirds his composition, with the horizontal and vertical axes often reiterated even if color plays an unprecedented structural role, and some sense of symmetry is usually present. Even when he departs from these conventions, as in Water Lilies and Agapanthus of ca. 1914–17 (fig. 14), cropping and the disposition of the motifs across the surface suggest that Monet is mindful of the overall shape of the canvas. Mitchell finds other ways of organizing her paintings, almost as if such modernist procedures had themselves to be interrogated. There are plenty of marks and shapes in her work that reiterate the shape of the canvas, including her penchant for dark vertical strokes along the bottoms of paintings, an almost jocular recollection of the inclusion of a foreground traditional in Western landscape painting. Her Plowed Field from 1971 is positively Hans Hoffmannesque in its insistence on rectangular fields of color, though its chronological and stylistic difference sets it apart from the rest of her work in the show. Mitchell is, however, most captivating when she plays with structure and symmetry and threatens to undermine them. In Red Tree from 1976 (fig. 15) she becomes engrossed with a small area just to the right of the center of the canvas, changing her stroke and palette, as if forgetting the overall shape and larger motif of the painting. In Beauvais from 1986 (fig. 16), the diptych is united by white strokes along the adjoining edges of the canvas that mirror the shape of one another. There is symmetry in the areas of forest green at the top outer corners of the diptych and also, though more vaguely, in the areas of blue paint, but there is hardly any at all in the areas of kelly green paint and red strokes. The edges of some strokes are extraordinarily crisp; those of others not at all. Almost everything seems provisional, experimental. A similar play between the two panels is present in Cypress (1980). Other paintings, in particular Row Row (fig. 17) and South (1989), explore various ways of achieving depth or emphasizing surface by varying certain effects of color, texture, and overlapping strokes in different panels. For example, in Row Row, the yellow strokes in the left panel are generally applied on top of the other strokes, and they appear to come forward in space, yet the purple strokes on the right, also painted on top, nonetheless recede. Many times, Mitchell’s diptychs seem to juxtapose two panels that are governed by a similar procedure regarding facture, color, composition, or some other formal element, but the panels are different enough to suggest that in fact no procedure is essential or necessary—that there is no singular or perfect way of proceding. Whatever Mitchell took from Monet—and it was a lot—her restlessness and experimentation make him appear comfortable and settled in his ways.

The wall text and labels accompanying the exhibition were straightforward and concise, geared toward engaging the general public. A recording by the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra of Debussy’s “Nocturnes” (admired by both Monet and Mitchell) played softly throughout the galleries. There was an “Explore Lab” where visitors could draw their own landscapes based on images provided by Forest Park Forever, a private nonprofit conservancy that partners with the city of St. Louis. In the same room played excerpts from two films: one of Monet from Sacha Guitry’s “Ceux de chez nous” (1915) and one of Mitchell from Angeliki Haas’s “Joan Mitchell in Vétheuil” (1976). Monet and Mitchell rarely appear without a cigarette in hand or mouth; Monet discloses that he starts the day with a piece of andouille sausage, a glass of white wine, and a cigarette, before devoting the rest of it to painting. Those were different times . . .

This exhibition focused on the twentieth century, as it featured one major modernist working at the beginning of the century and another working at the end of it. It relates to the nineteenth century, however, because it links one of the dominant figures of this period to the tradition of painting that followed out of his work and impressionism more generally. In this respect, it continues a series of important exhibitions curated by Kelly at the SLAM focused on French nineteenth-century art and sometimes on its legacy—shows like Millet and Modern Art: From Van Gogh to Dalí (2020), Paul Gauguin: The Art of Invention (2019), and Degas, Impressionism, and the Paris Millinery Trade (2017). While producing these exhibitions, all of which have been of the highest quality, the museum has maintained a slate of other exhibitions that are admirably diverse in terms of the identities of the artists shown, the global range of the art, and the types of media included. French nineteenth- and twentieth-century modernism may not seem as necessary or liberating as it did in the twentieth century, but SLAM has kept it vital and integrated it into a larger art historical picture.

Notes

[1] Michael Leja, “The Monet Revival and New York School Abstraction,” in Monet in the 20th Century, ed. Paul Hayes Tucker (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 98–108.

[2] Clement Greenberg, “The Later Monet,” first published in Art News Annual 26 (1957), reprinted with substantial revisions in Clement Greenberg, The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 4, Modernism with a Vengeance, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 3–11.

[3] Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 4 (Lausanne and Paris: La Bibliothèque des Arts, 1985), no. 1902.