American Art History Digitallysponsored by the Terra Foundation for American ArtFrom Zuni to Dupont Circle: Isabel and Larz Anderson’s Native American CollectionInteractive Feature

by Stephen T. Moskey and Isabel L. Taube

Stephen (Skip) T. Moskey is an independent scholar who writes about American cultural history, focusing especially on the intersection of social status, domestic architecture, and landscape design in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He is coauthor of The Turkish Ambassador’s Residence and the Cultural History of Washington, D.C. (Istanbul: Istanbul Kültür University, 2013) and author of Larz and Isabel Anderson: Wealth and Celebrity in the Gilded Age (Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, 2016). Recent projects include an article for White House History Magazine on Woodrow Wilson’s 1918 transatlantic voyage to the Paris Peace Conference and an edited volume of the collected letters of Elizabeth Kilgour Anderson. Current projects include a social and architectural history of the first Embassy of France in Washington, DC, and a biography of Theodore Frelinghuysen Dwight, Henry Adams’s literary secretary and archivist.

Email the author: skipmoskey[at]gmail.com

Isabel L. Taube has taught art history at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey; the School of Visual Arts, New York; and Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, and has curated exhibitions at the Frick Art and Historical Center, Pittsburgh; the SVA Galleries, New York; and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. She is also the comanaging editor of Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide. Her current book project focuses on the meaning and impact of eclecticism on nineteenth-century interiors and their representation. This study builds on her previous work on the US painters William Merritt Chase and Walter Gay.

Email the author: taubeisa[at]gmail.com

Citation: Stephen T. Moskey and Isabel L. Taube, “Interactive Feature,” in Stephen T. Moskey and Isabel L. Taube, “From Zuni to Dupont Circle: Isabel and Larz Anderson’s Native American Collection,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 2 (Autumn 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.2.24.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Scholarly Article|Interactive Feature|Project Narrative

Table of Contents

Introduction

Anderson House (1902–5)

Main Entrance

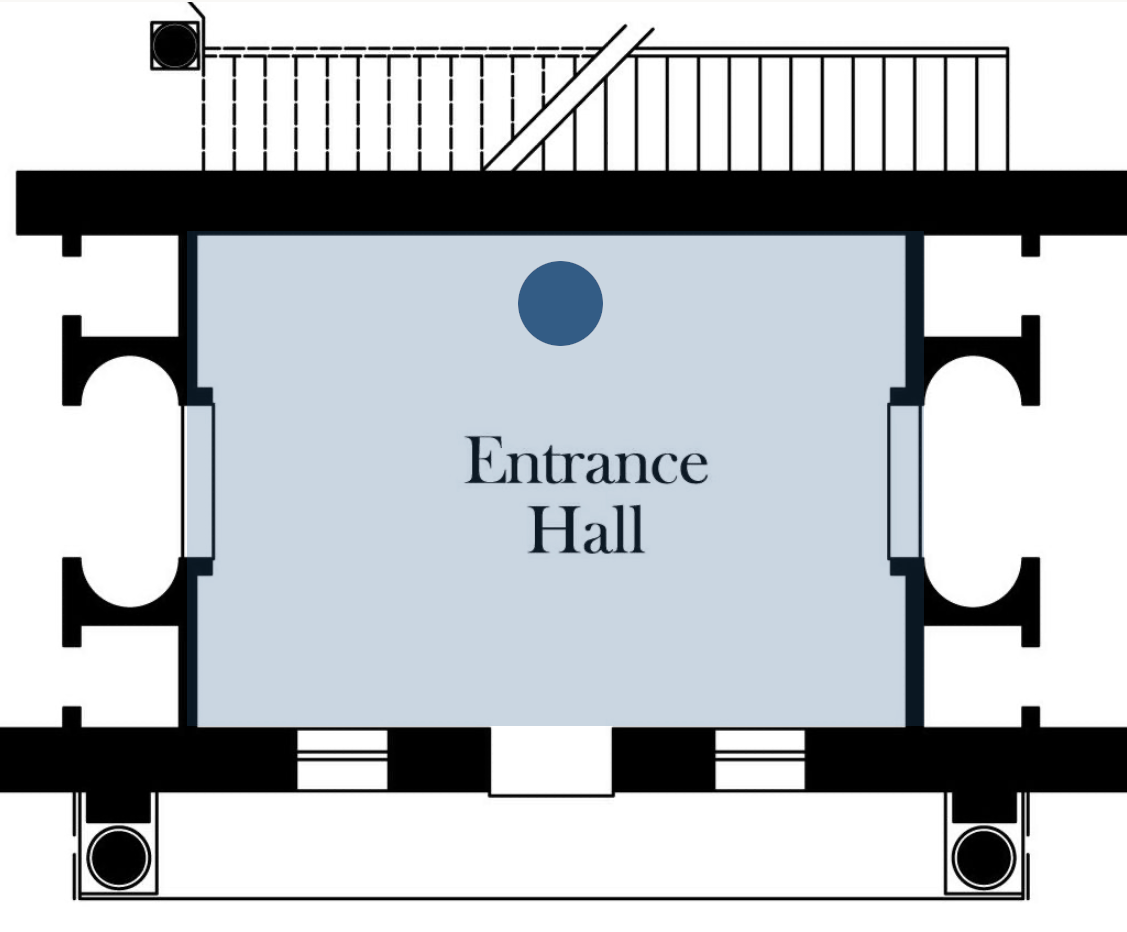

Entrance Hall

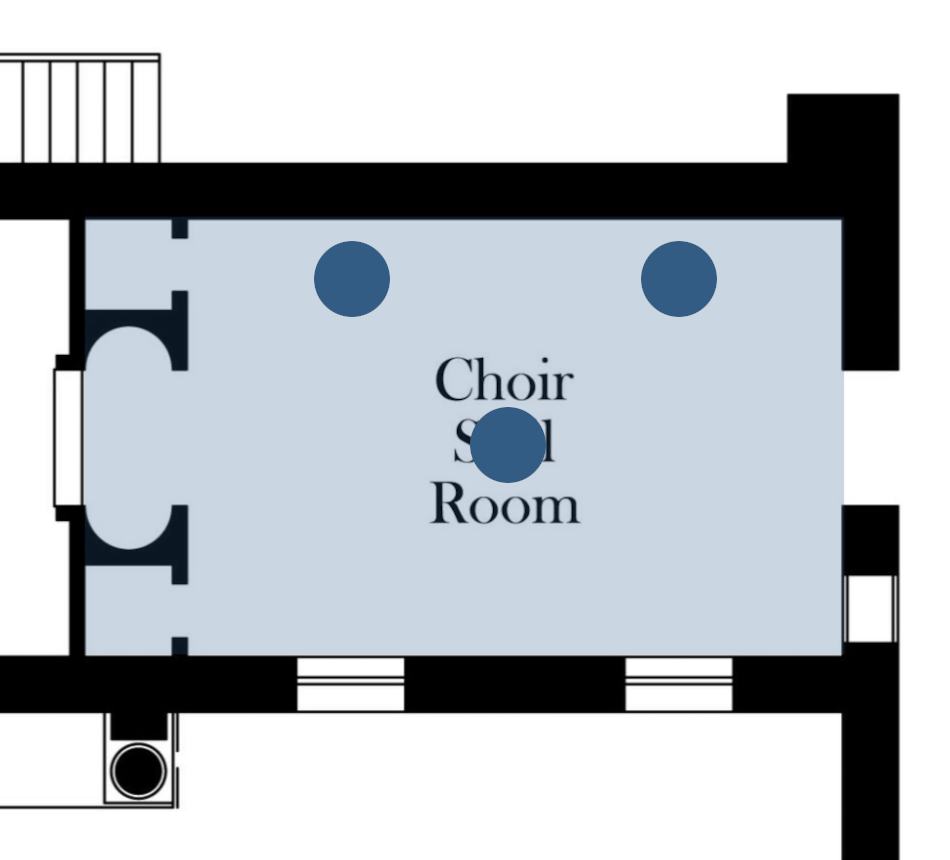

Choir Stall Room

Great Stairs Hall

Cincinnati (or Key) Room

French Room

English Room

Gallery

Dining Room

Saloon

Red Library

Winter Garden

Billiard Room

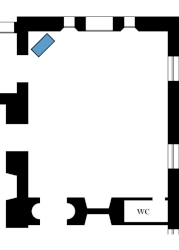

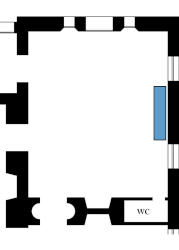

This digital component, with the aid of floor plans and photographs, offers a virtual tour that approximates the path and experience of guests who came to Anderson House in Washington, DC, in the early decades of the twentieth century for an evening dinner party of about twelve to fourteen couples, including Isabel Weld Perkins (1876–1948) and Larz Kilgour Anderson (1866–1937). The house offered a succession of rooms that guests moved through over the course of an evening’s entertainments, from arrival to greetings to having cocktails to dinner and then, finally, to after-dinner coffee, cordials, and conversation, accompanied by live music. Each room presented guests with a different ambience and a different experience of design, lighting, and, most importantly, art and other objects from the Andersons’ collections, displayed prominently in carefully planned, eclectic installations that served as hallmarks of their cosmopolitan identity. In each room, particular objects made reference to both the Andersons’ Anglo-European ancestry and their travels to places with what they regarded as exotic cultures. The tour begins on the ground floor with several rooms used for arrival and gathering before ascending the main stairs to the piano nobile (literally “noble floor”; the principal floor of a large house), where greetings and introductions as well as cocktails and dinner took place, and then culminates in a return to the ground floor where a series of rooms offered spaces for after-dinner entertainment. The only representation of a Native American person appeared in the mural on the ceiling of the Cincinnati (or Key) Room where guests were greeted by the Andersons, and Native American pottery was displayed in the Saloon, the Winter Garden, and the Billiard Room, all spaces used for after-dinner entertainment.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Front façade in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

Anderson House, located at 2118 Massachusetts Avenue NW, in Washington’s Dupont Circle neighborhood, was the winter home of Isabel and Larz Anderson. It was designed by the Boston firm of Arthur Little (1852–1925) and Herbert W. C. Browne (1860–1946) starting around 1901, and construction began in 1902 and was completed in 1905. The house comprised forty-five thousand square feet and ninety-five rooms, including bathrooms, storage, and service areas. Its total cost, including land and outbuilding, was $838,000 (approximately $25.3 million in 2023). The Andersons took occupancy of the house in March 1905, several years before its furnishing and decorating were completed.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Driveway, front door, and portico columns in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

As guests arrived for a dinner party, they were dropped off under the portico and ushered through the mansion’s broad, paneled door into the Entrance Hall.

Plan of the ground floor of Anderson House redrawn by Harry I. Martin III in 2015 from the original Little and Browne blueprints in the collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image © Stephen T. Moskey.

This piece is described in the inventory of 1911 as “1 Old bronze statue of Buddha seated in lotus blossom, right hand raised in benediction; halo decorated with figures in relief. Inscriptions on costume. . . . Perfect.”[8] It measures 90 x 40 in. (229 x 102 cm), and in 1910 sat on a block base 52 in. (132 cm) square. The base was redesigned for its later move to an outdoor installation in the garden by the Society of the Cincinnati, as seen in this photograph. Larz described the purchase of this object in the inventory: “After having unsuccessfully sought a bronze Buddha while on trips to Japan in 1888 and 1897[.] This one was acquired from Mssrs. [A. A.] Vantine in 1903.”[9] By 1903, Vantine was a well-established New York dealer for Japanese antiques and handicrafts.

The front Entrance Hall, known during the Anderson era as the Lobby, provided arriving guests with their first view of the interior of the house. At the time of Frances Benjamin Johnston’s photograph in 1910, the Entrance Hall was furnished and decorated sparsely with fewer than a dozen items that allude to the Andersons’ interest in and travel to Asia and Europe: religious objects from Japan and India and wooden seating from Holland and Italy.

After arriving in the Entrance Hall, guests would turn to the right and (see floor plan) through the door flanked by two bronze Japanese-temple lanterns.

Left: Plan of the ground floor of Anderson House redrawn by Harry I. Martin III in 2015 from the original Little and Browne blueprints in the collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image © Stephen T. Moskey.

Right: Little and Browne (architecture firm), Entrance Hall looking west into the public side of the house in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

Plan of the ground floor of Anderson House redrawn by Harry I. Martin III in 2015 from the original Little and Browne blueprints in the collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image © Stephen T. Moskey.

This room was lit by what Larz called an “old Italian silver font-shape sanctuary lamp with pear-shape pendant of embossed figures and flutes” that was “fitted to electricity with Baccarat bead globe.”[12] On the south wall of the room, two electrified, Venetian gilded-polychrome torches with kneeling angels holding candlesticks provided supplemental illumination for the paintings above. These torches were acquired from the firm of Edward F. Caldwell & Company of New York, known for providing both antique and custom-designed lighting fixtures to numerous US churches, public buildings, and residences, including the White House.[13]

This photograph shows a view of the ceiling and east-end frieze with modern illumination. The emblems on the frieze above the paneling, from left to right, are the Order of the Crown of Japan; Military Order of the Spanish-American War; and Grand Officer of the Order of the Crown of Italy. The ceiling includes small cartouches and squares displaying the seals of Phillips Exeter Academy and of Harvard College, where Larz was educated, and the signal of the Andersons’ houseboat, the S. S. Roxana.

In the Andersons’ time, the Choir Stall Room was also called the Ante-Camera Stall Room or sometimes the Inner Hall. Serving as a transitional space between the Entrance Hall and the Great Stairs Hall and continuing the ecclesiastical character of the entry space, it was fitted with carved walnut paneling that had been removed from an unidentified church in Italy. The Andersons acquired the panels in 1905 from the antiquarian firm of E. & C. Canessa in Naples, Italy.[10]

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Choir Stall Room in 2015, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Bruce M. White, 2015.

This photograph of 2015 taken from the west end of the Choir Stall Room shows that the complexity and ornateness of the Italian woodwork and lighting fixtures harmonized with the complexity and lustrous painted surfaces of the ceiling and frieze above.

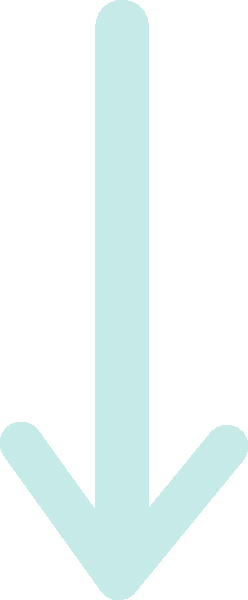

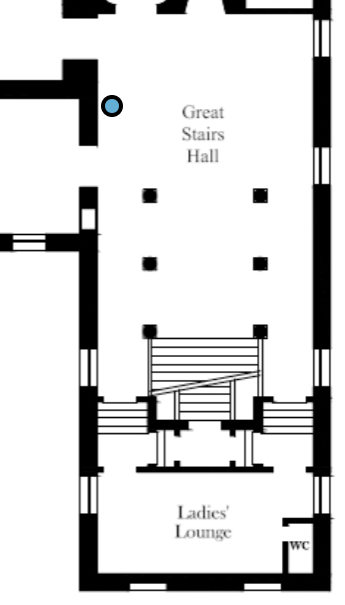

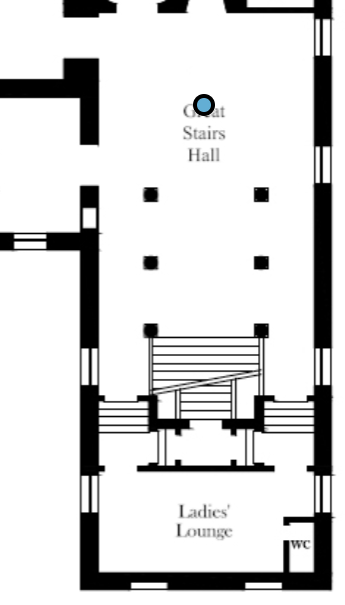

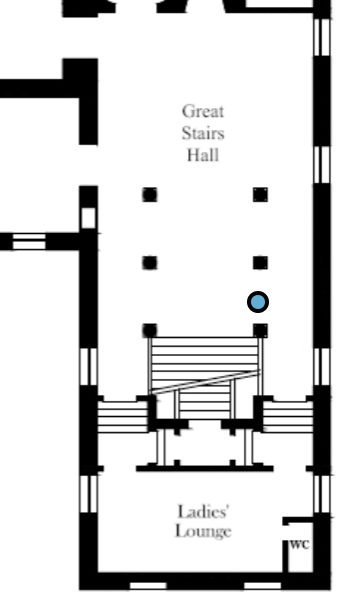

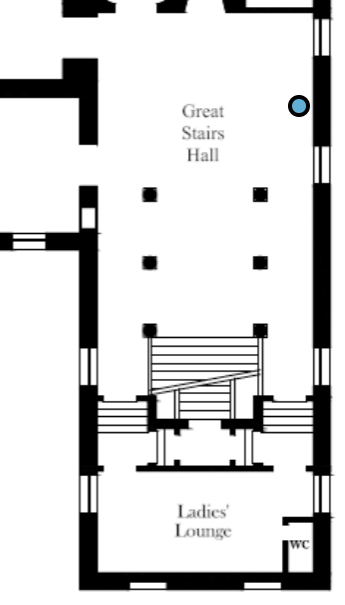

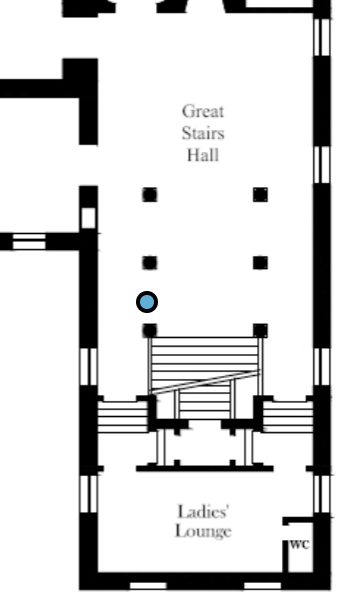

This room, known in the Andersons’ time as the Main Staircase Hall or the Great Stairs Hall, was an area where guests could remove their coats and get ready (see floor plan).

Plan of the ground floor of Anderson House redrawn by Harry I. Martin III in 2015 from the original Little and Browne blueprints in the collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image © Stephen T. Moskey.

Larz acquired this “Mexican carved walnut confessional chair” (location unknown) from the early seventeenth-century Córdoba Cathedral in Mexico. In his inventory of 1911, he notes that he obtained it directly from a priest at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Córdoba, “in exchange for a contribution to the repair of the church” that the bishop had approved.[15] The piece measures 108 x 72 in. (274 x 183 cm). The Andersons hung a framed postcard of the cathedral on the front of the confessional to document its provenance. Though the confessional may seem out of place in these secular surroundings, its decoration harmonizes with that of the Great Stairs Hall. In particular, the shield at the top of the confessional incorporates a stars-and-stripes design that recalls the US flag and the themes of war and patriotism in the nearby murals.

The grisaille trompe l’oeil murals of the Great Stairs Hall of Anderson House were painted in 1909 by the Italian artist Oreste Paltrinieri (1873–1966). Larz described in his journal the genesis of this panel’s design: “Years ago I bought an ‘Ambassador’s Box,’ a silver box with ink well and place for pens and sealing wax, such as was presented to English Ambassadors ‘on their appointment’ in the old days, although it didn’t seem then that I should ever be able to make proper use of it: —but here it is now in its proper place: and I had ‘cheek’ enough to have this box design worked into the fresco work over the fireplace in the great staircase hall of the Washington house, to represent my career in Diplomacy (with swords, and ‘trophies’ of my own and my Father’s military services, etcetera) even before I had a right to do, or even an evident hope.”[17]

Larz described this piece as a “Hindoo antique stone idol” acquired from Watson and Company in Bombay (now Mumbai) on the Andersons’ wedding trip to India in 1899.[16] It measures 31 x 18 in. (79 x 46 cm). The placement of this object at a geometrically central position in a space otherwise dominated by Christian liturgical objects suggests that Larz wished to highlight both its similarity to other pieces (religious statues) and differences from those same pieces (Hindu versus Christian, male versus female). It is now displayed on the floor in the Gallery of the piano nobile at Anderson House.

The Great Stairs Hall continued the ecclesiastical character of the Choir Stall Room. Dark, heavy pieces of European domestic and ecclesiastic furnishings were placed at intervals along the walls, some of which referenced a specific liturgical activity like preaching or confessing. Religious figures from both Eastern and Western religions; secular sculptures; and architectural fragments, all placed in careful and well-spaced juxtaposition to one another, gave the Great Stairs Hall a processional, religious character that seems to recall the nave of a church.

The 1911 inventory describes this piece as an “old Spanish carved walnut figure of a crowned Madonna and Child.” In a handwritten notation, Larz further describes it as an example of “Spanish Gothic carving,” which thus dates it to circa thirteenth-to-fifteenth century. The Andersons acquired this statue on a trip to Madrid in 1906.[19] During the Anderson era, it was displayed in the Great Stairs Hall in juxtaposition with the Lord Shiva and His Wife Parvati sculpture, setting up a dialogue between Christianity and Hinduism.

The inventory of 1911 identifies this object as an “Old Spanish” statue that the Andersons acquired in Madrid in 1906. Larz thought this statue might have been of Saint Margaret, a saint venerated in the Anglican Communion, of which he was a member.[22] When the item was deaccessioned by the Society of the Cincinnati in 2000, a Sloan’s appraiser identified it as possibly early seventeenth-century Flemish.

In the inventory of 1911, Larz explains how he came to acquire six of these large Spanish tobacco jars (height of each: 25 in. [64 cm]). The Andersons traveled to Spain in 1906 with the intention of purchasing these jars directly from the manufacturer, but they were unable to do so. The jars “had been sold out of a factory in Sevilla a while before our visit,” Larz wrote, and were already on their way to the United States. By the time the Andersons returned to New York, “[the jars] were in a dealer’s hands (Watson of New York),” and they then purchased them from that firm.[23]

In the 1911 inventory, this sculpture, which the Andersons acquired on a trip to Madrid in 1906, is catalogued as an “old Spanish Mexican carved wood gilt and polychrome group of St. Anne holding on [her] knee [the] Madonna and Child.”[20] In a handwritten notation, Larz explained, “it is only in Spain that are found groups including the Christ Child, his mother and grandmother.”[21] During the Anderson era, it was placed in the Great Stairs Hall at the bottom of the staircase on the opposite side from the Crowned Madonna and Child, and it, too, contributed to the dialogue between Christianity and Hinduism in this room.

One of the main architectural features of the Great Stairs Hall is the six columns that recall the nave of a church or cathedral, furthering the ecclesiastical character of the space already evident with the confessional, the pulpit, and other pieces of church furniture in the room. In the inventory of 1911, Larz emphasized this connection to church architecture when he noted that, as shown in this photograph, the columns were sometimes draped in “old Spanish rose color velvet panels” as was often done in Spanish churches “on ceremonial occasions.”[18] This ecclesiastical reference is also continued in the arrangement of several statues of Christian female saints, the Madonna and Child, and female divines placed on pedestals and bases in front of columns, an arrangement that suggests the placement of statuary throughout a church sanctuary for devotional purposes.

Larz acquired this “Mexican carved walnut confessional chair” (location unknown) from the early seventeenth-century Córdoba Cathedral in Mexico. In his inventory of 1911, he notes that he obtained it directly from a priest at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Córdoba, “in exchange for a contribution to the repair of the church” that the bishop had approved.[24] The piece measures 108 x 72 in. (274 x 183 cm). The Andersons hung a framed postcard of the cathedral on the front of the confessional to document its provenance. Though the confessional may seem out of place in these secular surroundings, its decoration harmonizes with that of the Great Stairs Hall. In particular, the shield at the top of the confessional incorporates a stars-and-stripes design that recalls the US flag and the themes of war and patriotism in the nearby murals.

Larz described this piece as a “Hindoo antique stone idol” acquired from Watson and Company in Bombay (now Mumbai) on the Andersons’ wedding trip to India in 1899.[25] It measures 31 x 18 in. (79 x 46 cm). The placement of this object at a geometrically central position in a space otherwise dominated by Christian liturgical objects suggests that Larz wished to highlight both its similarity to other pieces (religious statues) and differences from those same pieces (Hindu versus Christian, male versus female). It is now displayed on the floor in the Gallery of the piano nobile at Anderson House.

possibly Saint Margaret

The inventory of 1911 identifies this object as an “Old Spanish” statue that the Andersons acquired in Madrid in 1906. Larz thought this statue might have been of Saint Margaret, a saint venerated in the Anglican Communion, of which he was a member.[27] When the item was deaccessioned by the Society of the Cincinnati in 2000, a Sloan’s appraiser identified it as possibly early seventeenth-century Flemish.

The 1911 inventory describes this piece as an “old Spanish carved walnut figure of a crowned Madonna and Child.” In a handwritten notation, Larz further describes it as an example of “Spanish Gothic carving,” which thus dates it to circa thirteenth-to-fifteenth century. The Andersons acquired this statue on a trip to Madrid in 1906.[30] During the Anderson era, it was displayed in the Great Stairs Hall in juxtaposition with the Lord Shiva and His Wife Parvati sculpture, setting up a dialogue between Christianity and Hinduism.

The Andersons acquired this carved walnut pulpit (height: 144 in. [289.56 cm]; location unknown) in Florence in 1899. According to Larz, it was “supposed to be the work of [the Italian Renaissance sculptor, Andrea] Riccio [1470–1532].”[26] It is supported by kneeling angels and includes statues of disciples and bishops as well as panels representing scenes from the life of Christ.

In the 1911 inventory, this sculpture, which the Andersons acquired on a trip to Madrid in 1906, is catalogued as an “old Spanish Mexican carved wood gilt and polychrome group of St. Anne holding on [her] knee [the] Madonna and Child.”[28] In a handwritten notation, Larz explained, “it is only in Spain that are found groups including the Christ Child, his mother and grandmother.”[29] During the Anderson era, it was placed in the Great Stairs Hall at the bottom of the staircase on the opposite side from the Crowned Madonna and Child, and it, too, contributed to the dialogue between Christianity and Hinduism in this room.

Plan of the ground floor of Anderson House redrawn by Harry I. Martin III in 2015 from the original Little and Browne blueprints in the collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image © Stephen T. Moskey.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Grand staircase with José Villegas Cordero, The Triumph of the Dogaressa, 1882–93, in 2015. Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Bruce M. White, 2015.

The staircase leading from the Great Stairs Hall to the piano nobile was then, as now, dominated by the massive painting The Triumph of the Dogaressa (1882–93) by José Villegas Cordero (Spanish, 1844–1921). It measures 192 x 295 in. (488 x 749 cm) framed and fills almost the entire wall on the landing. It depicts the end of a yearlong celebration, from 1423 to 1424, of the coronation of the 65th Doge of Venice, Francesco Foscari (1373–1457), and his wife, the Dogaressa Marina Nani (ca. 1400–73). The painting’s brilliant colors and the ceremonial splendor of its subject helped set the stage for an evening at Anderson House.

Floor plan of the piano nobile of Anderson House redrawn by Harry I. Martin III in 2015 from the original Little and Browne blueprints in the collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image © Stephen T. Moskey.

Larz called the ceiling murals by US artist Harry Siddons Mowbray (1858–1928) “an Apotheosis of the Spirit of the Cincinnati.”[33] In addition to two large, central medallions depicting a Triumphant Republic and the Genius of the Cincinnati, four blue-and-white panels in high relief portray scenes from US history, including one that represents a Native American titled “The Pioneers.”

One of the four blue-and-white panels represents two white settlers seated in a canoe adjacent to the shore and a Native American standing next to a tree nearby. The subject of the panel is identified in the inventory of 1911 as “The Pioneers” and is described as “Symbolizing the Exploration and Settlement of the Country and the Contact of the Red and White Races.”[34] This is the only decorative element from the Anderson era referencing Native American culture or history currently on display in Anderson House. The Native American appears as a primitivized, native type, wearing only a feathered headdress and a loincloth. His standing pose, with his right leg on the ground, his left leg still in the canoe, and his left hand resting on a tree trunk suggests that he may be portrayed as a scout or guide who has shared his mode of travel (the canoe) with the pioneers, facilitating the white men’s exploration and settlement rather than impeding it. The three men appear as a unit, a peaceful group with their weapons lowered and pointed away from each other. This panel conforms to the version of US history advanced by the white elite during this period that co-opts Native Americans and their culture in the figuring of white national identity in the United States. In this ceiling panel, the Native American and the pioneers together constitute the white nation’s foundations: as ethnic studies scholar Shari Huhndorf contends, “Although white America was literally built on the destruction of Native America, the stories European Americans told about themselves as the [nineteenth] century drew to a close also depended on the symbolic resurrection of the Indian as the originary figure of the nation.”[35]

These photographs show one of four historically themed murals in the Key Room that were executed in 1909 by US artist Harry Siddons Mowbray (1858–1928). Entitled The Society of the Cincinnati Was Instituted in Peace After Revolution, it provides an allegorical scene of the founding of the society: President George Washington presents a diploma of membership to the Marquis de Lafayette, while other US Revolutionary military officers stand grouped around the dais. Larz’s great-grandfather Col. Richard Clough Anderson (1750–1826) is depicted in the scene, as is Isabel Anderson, who was the model for the winged personification of Peace seen peeking out from the top right edge of the color photograph, above the allegorical representation of War in a gold helmet.

These photographs show one of four historically themed murals in the Key Room that were executed in 1909 by US artist Harry Siddons Mowbray (1858–1928). Located on the south wall of the room, this scene entitled The Order of the Loyal Legion Was Born out of Cruel Civil War portrays the development of the US Civil War from a Northern perspective, supported by the Andersons. The right side of the mural presents an event that marked the outbreak of the war: the Union-held Fort Sumpter, under the command of Larz’s great-uncle, Major Robert Anderson (1805–71), burns in Charleston harbor following an attack by Confederate forces on April 12, 1861. The central group depicts the South preparing to do battle with the North in an allegorical manner: a female figure signifying the South with a cotton branch in her arm raises her sword to a floating male figure symbolizing “War Bursting Forth” while the Republic, identified by the shield bearing a Union emblem, extends his left arm as though to hinder her. The left side of the mural represents the success of the North and its aims: Union troops led by Larz’s father, Colonel Nicholas Longworth Anderson (1838–92), march triumphantly to battle in the South, and an enslaved Black man is freed from his shackles by a white angel of Peace, representing the North’s goal of emancipation.[36]

This view shows two of the Key Room’s three tables (each 32 x 67 in. [82 x 170 cm]), surmounted by vitrines (16 x 67 in. [41 x 170 cm]) lined with green baize, where the Andersons displayed pieces of their Japanese lacquerware collection many of which were acquired in Japan on their honeymoon there in 1897. The collection included several paired boxes, one for writing utensils and one for paper.[37] The Georgian-style tables are decorated with lambrequins comprised of “carved basket[s] of flowers hung with two swags”[38] that complemented the floral imagery on the lacquerware and the “radiating acanthus leaves” on the circular, carved-and-gilded wood “electric candelabra”[39] (diameter: 40 in. [102 cm]) that hung from the center of the ceiling. Both the repeating natural motifs and the glossy surfaces of the objects and the murals would have visually unified the otherwise disparate contents of this room.

A large (height: 72 in. [183 cm]) Japanese bronze statue of Kannon (location unknown), the Buddhist goddess of mercy and compassion, standing in a lotus leaf, stood on the right side of the window in the southwest corner of the Key Room. Isabel appears to have understood the spiritual significance of Kannon in Buddhism, and devoted two pages of her book The Spell of Japan to the story of this goddess. She noted that Kannon was “often compared to the Christian Madonna,” thus articulating a cross-cultural connection between these female Buddhist and Christian divines.[40]

At the top of the grand staircase, guests entered a reception area called the Key Room, a reference to the Greek meander or key design of its marble floor. The Andersons also sometimes called it the Cincinnati Room, a reference to the wall murals depicting the founding of the Society of the Cincinnati and the early history of the city of Cincinnati, Ohio, and a painted ceiling that Larz dubbed “an Apotheosis of the Cincinnati.” The Key Room was the anteroom to the entire piano nobile. It was here that the Andersons and their guests of honor greeted guests arriving from the floor below, and they were reminded of Larz’s family’s contribution to the early history of the United States and the founding of the Society of the Cincinnati.

Left: Harry Siddons Mowbray, Detail of The Order of the Loyal Legion Was Born out of Cruel Civil War, 1909, in 1910. Oil on canvas. Anderson House, Washington. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

Right: Little and Browne (architecture firm), Detail of the Key Room looking north into the Great Stairs Hall in 1910 showing Kannon sculpture, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

Left: Harry Siddons Mowbray, The Order of the Loyal Legion Was Born out of Cruel Civil War, 1909, in 1910. Oil on canvas. Anderson House, Washington. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

Right: Little and Browne (architecture firm), Key Room looking north into the Great Stairs Hall in 1910 showing Kannon sculpture, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

The arrangement of the Key Room connects the Kannon to another female figure that Larz referred to simply as “the South,” a central figure in the nearby Civil War mural by US artist Henry Siddons Mowbray (1858–1928).[41] Both figures are in a direct line of sight to each other that suggests a tacit, sympathetic relationship between them: a figure representing compassion and mercy connected to another figure representing defeat and loss. Their relationship to each other is further established by similarities in costume and pose. Their hand gestures mirror one another and reinforce each figure’s significance: Larz described the position of the Kannon’s raised right hand as expressing “an attitude of blessing,”[42] whereas the South uses her raised left hand to tender her sword to an allegorical male figure representing “War Bursting Forth.”[43] The Andersons created several installations throughout the public rooms of the house in which figures representing East and West were juxtaposed, thus contributing to the eclecticism of the interiors and emphasizing the Andersons’ cosmopolitan outlook on the world.

After greeting the Andersons in the Key Room, (see floor plan). The French and English themes of these two rooms reflected the cultural importance of these two countries during a time when US elites like the Andersons looked to France and Great Britain for guidance on taste in art, literature, and fashion.

Floor plan of the piano nobile of Anderson House redrawn by Harry I. Martin III in 2015 from the original Little and Browne blueprints in the collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image © Stephen T. Moskey.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Northwest corner of the French Room in 2013, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph courtesy of Bruce Guthrie.

The French Room was the first of two adjacent drawing rooms on the piano nobile where the Andersons and their guests gathered for cocktails before dinner. It was not photographed by Frances Benjamin Johnston in 1910, likely because its décor was undergoing a significant alteration around this time as the Andersons were negotiating the purchase of a set of four tapestries, finally acquired in 1911, three of which are visible in this photograph from 2013.

Tapestry of silk, linen, and wool from the Gambara Series, also known as the Arbor or Flemish Renaissance Series, Flemish, late 16th century, in the French Room in 2023, Anderson House, Washington. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Artwork in the public domain; photograph by Stephen T. Moskey.

The Andersons’ Italian Garden, one of several themed gardens and landscapes on their estate named Weld in Brookline, Massachusetts, was designed by the US artist and landscape architect Charles A. Platt (1861–1933) in 1901, with plantings by the Olmsted Brothers in 1902. The gardens included Italian, English, Japanese, and Chinese; an outdoor theater-in-the round garden called the Rond Point; kitchen and cutting gardens; and large bonsai and topiary collections that were displayed in different locations around the estate.[52] This photograph shows one of three large pergolas around the perimeter of the Italian Garden. The Andersons often used them as the setting for formal luncheons and dinners, afternoon tea, or as a place to read and write. Indeed, a direct reference to their Italian Garden and its pergolas appears elsewhere in the house, in a mural in the Winter Garden, thus integrating an important reference to their other home into Anderson House.

The inventory of 1937 describes this panel, which measures 137 x 127 in. (348 x 323 cm), as “depicting two vases of flowers beneath a vine-wreathed pergola with five marble columns, and two figures of nymphs in the left foreground gathering flowers; naturalistic border of birds, animals, and fishes, in air, land, and sea[.] Brussels mark: B B [Brussels–Brabant] and shield in the lower selvage, and weaver’s mark in right selvage.”[50] Beyond their role in establishing a French style for the room, the tapestries also had a more personal meaning for Isabel and Larz. The scenes in the tapestries could be interpreted as a subtle allusion to the , which Isabel once called “our enchanted garden” and which served almost as the spiritual core of their relationship.[51]

Little and Browne (architecture firm), North wall of the English Room in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

The English Room, adjacent to the French Room, provided another large area where guests could mix and mingle over cocktails. The room’s English appellation comes from its display of six portraits of British aristocrats and an English landscape.[53] While the room’s draperies, boiserie, chandelier, and decorative objects installed in symmetrical arrangements projected a formal quality, the overstuffed sofas and armchairs, upholstered in red-and-white floral chintz and yellow chinoiserie chintz, seemingly arranged in an almost haphazard manner, underscored the room’s primary purpose of facilitating social introductions and creating opportunities for casual conversation in a comfortable setting. The art and decorative objects in this room also would have conveyed to the guests that the Andersons were not only Francophiles but also Anglophiles who treasured exotic things like many British aristocrats.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), South wall of the English Room in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

The opulent formality of the floor-to-ceiling, golden satin window draperies and lighting fixtures of the English room contrasted sharply with the informality of the seating arrangements. Much of the decoration, including the intricately modeled papier-mâché ceiling decorated with what the inventory of 1911 describes as “medallions of musical trophies” and framed in “acanthus cartouches”;[54] the floral designs of the English chintz slipcovers on the seating; and the carved-and-gilded, bow-shaped wood cornice of the drapery installation with, as Larz described it in the inventory of 1911, “shell, acanthus scrolls and shell cartouche[s] at ends, in relief,” repeated the garden theme of the tapestries in the French Room.[55]

Little and Browne (architecture firm), West (left) and east (right) walls of the English Room in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photographs by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Images in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

The west and east walls of the English Room contained two identically installed displays: a portrait of The Duke of Wellington (ca. 1830) by the English painter John Simpson (1782–1847), with or after Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830), on the west wall, and what the Andersons purchased as a study for Lady Cockburn and Her Children (1773) by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–92), on the east wall, placed above identical glass-fronted display cases surmounted by two “rare old Chinese jade blossoming trees” housed in glass domes.[56] Stephen T. Moskey has posited that these two portraits served for the Andersons as a private, allegorical reference to their marriage and to their unfulfilled hopes of having a family. The presence of a small portrait of Isabel and her two prized Japanese crystal balls in front of the Wellington portrait, and an inkstand and drinking cup (symbolizing, perhaps, Larz as a writer and connoisseur of wine and spirits) in front of the Cockburn portrait, help establish this interpretation.[57]

Floor plan of the piano nobile of Anderson House redrawn by Harry I. Martin III in 2015 from the original Little and Browne blueprints in the collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image © Stephen T. Moskey.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Gallery looking east in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

At around eight o’clock, after the Andersons and their guests had mingled over cocktails in the French and English Rooms, dinner was announced by the chief butler. Guests were assembled in their order of social precedence for a procession down a long gallery to the dining room. Like the long galleries in English country houses built in the Elizabethan and Jacobean styles, this space runs along the width of the central core of the house, with windows along one side and art collections on display. Oftentimes long galleries are filled with portraits of family or royalty, and the inventory of 1911 indicates that the Gallery at Anderson House had family portraits in miniature mounted together in frames, including four of Isabel’s mother, Anna Minot Weld (1835–1924), and one of Larz’s mother, Elizabeth Coles Kilgour (1843–1917), as well as an oil painting of Isabel’s father, George Hamilton Perkins (1835–99).[58] Yet, the dominant impression was not of a family portrait gallery but of an opulent display of fine and decorative arts that had cosmopolitan and ecclesiastical, not just familial and hereditary, associations.

The inventory of 1911 describes three “old Spanish . . . carved gilt and polychrome” groups that were displayed in the Gallery, this one showing a detail from the Crucifixion.[62] The crucifix itself, missing, was likely a separate piece that was hung on a wall behind it. The two other groups, still on display in Anderson House, are of the Flagellation and the Last Supper. The decorative arts specialist Caren Pauley has identified the three pieces as likely colonial South American, rather than “old Spanish.” The table setting for the Last Supper scene (not shown) includes a roast guinea pig on a platter in the center of the table, a specialty in the Andean Plateau region since the Spanish colonial period.[63] At the time this photograph was taken, the Crucifixion scene was still displayed on the same sixteenth-century Italian walnut marriage chest and in front of the Diana tapestries shown in Johnston’s 1910 photographs of the Gallery.

Along the wall without windows were three panels from a set of eight Diana tapestries woven in the late sixteenth century in Brussels. They depict the ancient Roman goddess Diana, patroness of the countryside, of hunters, of crossroads, of the moon, and of childbirth.[60] The installations that the Andersons arranged in front of these mythological scenes reinforced the ecclesiastical character of the space. They not only included liturgical or religious objects, such as ecclesiastical vestments, religious-themed paintings and , a reliquary-like cabinet, a baptismal font, and two bishop’s stalls (later donated to Washington National Cathedral), but they also were arranged along the wall to suggest the effect of altars or devotional stations in the nave of a church. The illumination of the Gallery at night by four grand torchères with figures of the Apostles, one of which appears here on the right, may have further contributed to the ambience of a candlelit church interior. Larz likely sought to evoke the sumptuous interiors of Catholic churches, whose aesthetic would have appealed to a High Church (or Anglo-Catholic) Episcopalian like himself during this period.[61]

Installation in the Gallery on the south wall in ca. 1942, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by US Navy Department. Record Group 80, General Records of the Department of the Navy, Color Photographs of US Navy Activities, Series NAID: 147873838, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA II), College Park. Image in the public domain; image courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration (NARA II).

This installation by the Andersons illustrates the methodology they used to create cosmopolitan, eclectic installations throughout their homes. In this instance, unrelated objects are put together in an aesthetically pleasing, formally unified way. A Madonna and Child with Saints, Man of Sorrows, the Virgin, and John the Evangelist in Roundels Below by the Master of San Jacopo a Mucciana (Italian, 14th century)[64] is hung in the interstices of two panels from a late sixteenth-century series of Diana tapestries from the Brussels workshop of Jacques Guebels the elder (act. 1580–1605) and Jan Raes I (act. 1610–31), based on cartoons by the French painter Toussaint Dubreuil (1561–1602).[65] Below the painting, a “Japanese ceremonial long sword [tachi] in carved ivory sheath,” as described in the inventory of 1911, sits on a large, sixteenth-century Italian, inlaid marriage chest (38 x 78 in. [97 x 198 cm]), placed in a lacquered stand so that its curvature echoes Diana’s bow and visually connects with her right hand and arm.[66] Unidentified armaments including guns and daggers, possibly of “antique Moorish” origin, are laid on the top of the chest under the Japanese tachi.[67] This disparate group of objects is not only linked through curved and connecting forms but also by the repetition and harmony of colors.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Gallery looking east in ca. 1942, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by US Navy Department. Record Group 80, General Records of the Department of the Navy, Color Photographs of US Navy Activities, Series NAID: 147873838. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA II), College Park. Image in the public domain; image courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration (NARA II).

This rare color photograph of Anderson House was taken around 1942, when Isabel was still alive and the new owners of the house, the Society of the Cincinnati, were maintaining the interiors as they had been at the time of Larz’s death in 1937. Many of the installations in the Gallery seen in this photograph had remained unchanged, exactly as they were when first photographed more than thirty years earlier, in 1910, by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Other than the flash used to take the photograph, the only sources of lighting in this photograph were the four grand torchères along the left side of the Gallery.

After enjoying cocktails in the French and English Rooms, (see floor plan). This room, like the other rooms in the house they had already passed through, offered a new experience that must have been almost breathtaking.

Floor plan of the piano nobile of Anderson House redrawn by Harry I. Martin III in 2015 from the original Little and Browne blueprints in the collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image © Stephen T. Moskey.

Larz called the two busts placed high on the north wall of the Dining Room “Old Roman white marble busts of Emperors” that were “[f]ound during excavations by Norton,” a reference to the US archeologist and classicist, Richard Norton (1872–1918).[69] Norton was a friend of Maud Howe Elliott (1854–1948) and John Elliott (1858–1925) in Rome, who often advised the Andersons on artistic matters and may have been involved in the Andersons’ acquisition of these and other Roman antiquities.[70] The Andersons were fascinated by the civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome. In addition to his extensive travels in Greece and Italy, Larz had been educated in the classics at Harvard and knew Greek and Latin, and Isabel had a deep knowledge of Greek mythology. She once wrote: “As a child, I loved Greek mythology and peopled the mountains and vales of Greece—as I saw them in my imagination—with gods and goddesses.”[71]

The Dining Room walls were hung with five Brussels tapestries, still in place today. They belong to the Diana Series, the other three of which hang in the Gallery next door. While the Diana Series includes five scenes that feature the goddess Diana, there also are two images that may serve as allegorical representations of Diane de Poitiers (1500–66), the mistress and advisor of King Henry II of France (1519–59) and one that appears to represent King Henry II killing a dragon. The one in this photograph seems to portray Diane and Henry in a formal garden surrounded by a colonnade. The triumphal arch on the left behind the king is perhaps a reference to one of Henry’s victories in war.

Isabel Anderson devoted an entire chapter of her book The Spell of Belgium (1915) to Renaissance tapestries, and included in it her version of the history of the Diana Series, which previously was part of the Barberini collection in Rome. She also noted that she and Larz had acquired the borderless panel hung above the fireplace separately from the other panels. The panel had been stolen at some point in its history, and its border was cut off to remove identifying marks. “We were able to get it, so that now the set is once more complete after hundreds of years,” she said.[72]

Upon entering the room, guests would have immediately noticed that there were fewer brightly lit lamps and lighting fixtures than there had been in other rooms. Nonetheless, the Dining Room was illuminated brilliantly and dramatically. The main illumination came not from overhead fixtures or table lamps but from a candelabrum, a pair of candelabra, and candlesticks that were arranged on the table and held dozens of candles. These pieces were part of the Andersons’ extensive collection of silver garniture de table (a set of objects used to decorate a table).[68]

This lighting design seemingly dictated the type of objects that could be displayed here. Unlike in other public rooms in the house, there were no small objets d’art or vitrines filled with curiosities. The lighting in the room was not adequate for looking at such objects, and guests remained seated during the formal dinner and were not free to walk around the room. Thus, the collections displayed in the room had to be matched to both the lighting of the room and the constraints of a formal dinner. This offered the Andersons a unique opportunity to reintroduce to their guests two of their favorite art forms: Greek and Roman sculpture and Flemish tapestries.

The Saloon at Anderson house, by far the grandest and most impressive room, was hidden from view until guests exited the Dining Room after dinner and stood on the musicians’ balcony overlooking the brilliantly illuminated, immense space of the room below. From the balcony, (see floor plan) for after-dinner coffee and drinks, cigarettes, and entertainment.

Floor plan of the piano nobile of Anderson House redrawn by Harry I. Martin III in 2015 from the original Little and Browne blueprints in the collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image © Stephen T. Moskey.

A room this large was essential to the way evening events were planned. The Andersons often treated their guests to after-dinner musical performances in the Saloon. When they did so, they sometimes invited a hundred or more additional guests to join them for the entertainment. This was a custom that allowed hosts to show off their famous dinner guests to a larger local audience than could be seated at the dinner table. Isabel’s choice of performers and programs favored European musical traditions.[73]

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Saloon looking east in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

The Saloon, like other areas of Anderson House, incorporated several features common in English country homes. Larz had once seen a so-called floating staircase, like the one shown here along the left wall, in an unidentified house in England and had been struck by the fact that it was located “inside a room” rather than outside it.[78]

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Northeast corner of the Saloon in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

This photograph shows an example of the eclectic array of decorative objects arranged by the Andersons in the Saloon. Ecclesiastical architectural elements found in Catholic churches, like the Italian “antique red Verona marble spiral-turned columns with carved Ionic stone capitals,”[80] were combined with furnishings linked to royalty, including the “old Venetian carved gilt wood throne chair,”[81] likely made in Europe for export to the US market,[82] and reproduction Louis XV-style armchairs below a Louis XV carved-and-gilded wood girandole with eight electrified candle branches that was one of the main sources of ambient lighting in the room.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), West wall of the Saloon in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

The west wall of the Saloon is marked by a strict symmetry that helps establish it as the focal point of the room, centered on what Larz called an “antique Italian carved stone mantel” that was acquired for the Andersons in Rome in 1899 by the US artist John Elliott (1858/59–1925).[83] The elegant mantel is perfectly integrated with the Saloon’s immense interior architecture by the broken pediment, in Caen stone, mounted high on the wall above it. The break in the pediment’s peak is filled by an ILA monogram (the initials of Isabel and Larz Anderson) that also appears in the coffered ceiling.

Plan of the ground floor of Anderson House redrawn by Harry I. Martin III in 2015 from the original Little and Browne blueprints in the collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image © Stephen T. Moskey.

Five smaller, more intimate, less formal rooms were accessible directly off the Saloon, offering guests alternate areas they could visit during the after-dinner phase of the evening if they wanted to get away from the hub of activity and music in the Saloon. The Red Library offered a quiet space where guests could go for small-group conversation or a game of cards. The Winter Garden was actually an interconnected series of three rooms: a central garden area filled with plants and sculpture where Isabel might entertain her female friends, a Breakfast Room with a distinctly feminine character, and a Smoking Room where men could smoke. And, finally, the Billiard Room was a space where men could gather for cigars and games of pool.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Northeast corner of the Red Library in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

Located off the southeast corner of the Saloon, the Red Library housed the Andersons’ collection of several thousand volumes that reflected their interests. Their cosmopolitan tastes and knowledge of the world were based not just on their travel and education but also on knowledge and insights acquired from books. They were both voracious readers with interests that ranged across many disciplines, including art and architecture; American, English, and French history and literature; and diplomacy and politics. Isabel had a particular interest in modern British and US poetry.[86] The room was furnished with many of the same objects typical of libraries in English country houses owned by the privileged and wealthy: built-in bookcases, comfortable armchairs, a desk, a card table, busts, and picturesque landscapes, such as the one over the fireplace identified in the inventory of 1911 as “Hasbrock, 1868: Old Mill” (likely by the US artist Du Bois Fenelon Hasbrouck [1860–1934]).[87]

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Winter Garden looking west in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

The Winter Garden that ran along the southern exposure of the house provided the Andersons with an opportunity to delight their guests with the experience of enjoying beautiful displays of tropical flowers and foliage blooming indoors in winter. Here they could also share stories with their guests about their love of gardens, and especially their Italian Garden in Brookline designed by US artist and landscape architect Charles A. Platt (1861–1933). The flowers, foliage, trellises, mirrored walls, garden sculpture, and wicker furniture re-created on a small scale features of their indoor and outdoor gardens in Brookline. Isabel especially enjoyed giving her female guests a tour of the Winter Garden, with its natural surroundings associated with women and with Isabel specifically. It included among its botanical specimens specific flowers and foliage that she was especially fond of. But one of Isabel’s favorite things about the garden was that her beloved pet parrots were allowed to fly free there. She once wrote: “I love to sit in our winter garden, surrounded by palms and blood-red azaleas, pure white cyclamens and sweet-smelling lilacs. A bronze Bacchus peeps at me around a heather bush and a little marble faun looks out of the ivy climbing on the golden lattice.”[88]

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Winter Garden looking east in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

In addition to displaying exotic and garden varieties of plants and flowers, the Winter Garden was also a venue for exhibiting pieces of sculpture and pottery as well as “old Italian” architectural fragments from the Andersons’ collection. In this photograph, a Zuni k’yabokya de’ele (water jar) with a heart-line deer motif, repurposed as a jardinière, is displayed prominently on a rattan table near the center of the garden. On the left, a bronze reproduction of an antique sculpture from Pompeii of Narcissus forms part of a corner floral installation set on the floor against the glass doors of the Breakfast Room. Another bronze of “a conquering young Neptune, with his spear lifted,” as described by Isabel,[89] rises from a violet Brescia marble and alabaster fountain at the right, between the two floor-to-ceiling round columns. The Zuni deer jar shares space with reproductions of antique sculptures, creating the kind of eclectic arrangement that the Andersons favored.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Breakfast Room in the Winter Garden in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

The Breakfast Room in the Winter Garden provided a specific, visual connection to the Andersons’ home in Brookline. A mural by the German-US muralist Karl Yens (1868–1945) provided a panoramic view of what Isabel had once called their “enchanted” Italian Garden there.[90] Larz worked closely with Yens on the design of the mural to assure accuracy and then, after it was completed, “touched up” parts of the painting himself to correct details.[91] The mural was intended to create the illusion of standing on a raised walkway overlooking the Italian Garden, so accuracy was paramount. The Winter Garden might have even seemed to be an extension of the garden portrayed in the mural, to the point that it was furnished with green wicker chairs that matched those shown in the mural. The potted and cut flowers displayed throughout Anderson House for dinner parties, afternoon teas, or just for the couple’s own enjoyment all came from their extensive horticultural operations in Brookline. Even in the dead of winter, their greenhouses produced potted plants in full bloom, cut flowers for floral arrangements, and fresh fruit for the table. All of this was transported in weekly shipments by train from Boston to Washington.

Harry Siddons Mowbray, Detail of mural in the Smoking Room in the Winter Garden, ca. 1908–9, in 1910. Oil on canvas. Anderson House, Washington. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

If the Breakfast Room on the east end of the Winter Garden, with its mural and painted furniture, was a feminine space, then the west end of the Winter Garden was surely a masculine space. Identified on the original blueprints as the Smoking Room, this was a place where men could gather to smoke without women present.[92] Located just outside the Billiard Room, a venue for tobacco smoking and games of pool,[93] the Smoking Room was decorated with bespoke murals documenting Larz’s love of the automobile and the automobile trips he liked to take with Isabel by his side in the Washington area. The maps pictured in the detail of the mural in this photograph were done in what Larz called ‘old style’ and were commissioned from US muralist Henry Siddons Mowbray (1858–1928).[94] The Andersons’ houseboat, the S. S. Roxana is shown at anchor in the Potomac River, along with the sailing yacht Virginia that they chartered from time to time for trips to the Caribbean. The maps can be illuminated at night, suggesting they received special attention at evening functions when Larz could use them as props as he talked with his male guests about his local automobile travel and, farther afield, houseboat cruises along the East Coast of the United States.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Northeast corner of the Billiard Room in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

Located in the southwest corner adjacent to the Saloon and facing the garden, the Billiard Room functioned as a space for Larz to entertain his male guests after dinner in a club-like atmosphere with its “billiard and pool table,” brown oak paneling, comfortable armchairs, and, hanging on the walls, portraits of notable Washington men. Today it serves as a gallery for temporary exhibitions primarily on American Revolutionary history and the art of eighteenth-century warfare, and occasionally exhibitions about the Andersons themselves. The original Anderson furnishings and decorative objects have been relocated or sold.

Little and Browne (architecture firm), Northwest corner of the Billiard Room in 1910, Anderson House, Washington, constructed 1902–5. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Collection of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC. Image in the public domain; courtesy of The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

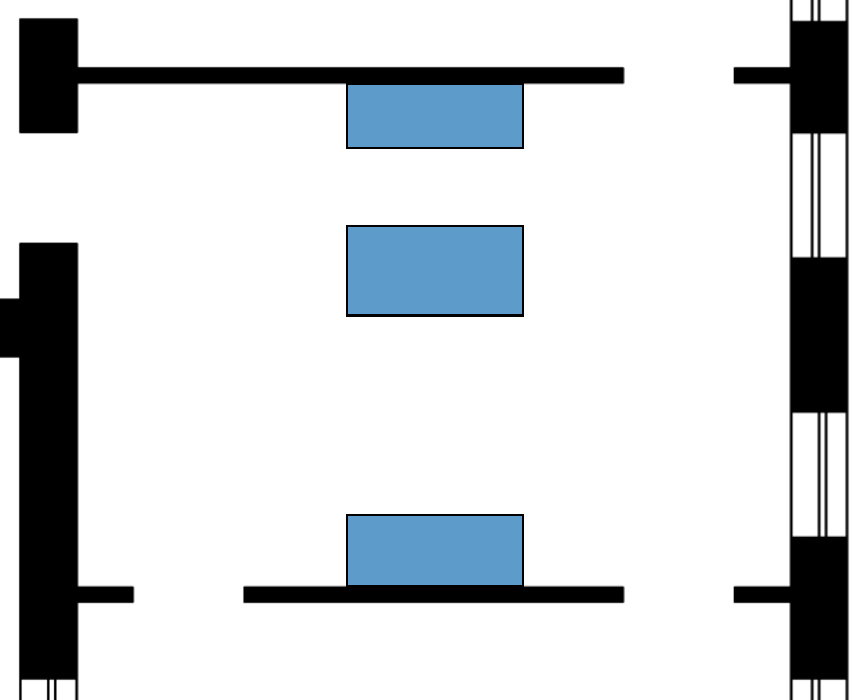

This photograph of the northwest corner of the Billiard Room includes the pottery from a variety of Southwestern producers and locations (Zuni, Acoma, Hopi, and possibly Laguna) stacked in an orderly fashion both inside and on top of a carved wood cabinet with glass doors and arranged together with a collection of Larz’s yachting flags and photographs of yachts owned by the Andersons and by the Weld branch of Isabel’s family. According to the inventory of 1911, there were fourteen pots, though they are not all visible in this photograph.[96] As discussed in more depth in the accompanying article, the Billiard Room exemplifies how Isabel and Larz incorporated Native American objects into their eclectic interior arrangements as a means to convey to visitors their actual and aspirational cosmopolitan identity.

Hanging on the walls of the Billiard Room, as seen in this photograph of the southeast corner, were sixty-nine “caricatures of well-known Washington characters,” all Larz’s acquaintances and friends, commissioned from US artist Clary Ray (1865–1916).[106] Isabel donated them to Washington’s Alibi Club after Larz’s death. Larz remarked in the inventory of 1911 that “this collection continually being added to painted by Clary Ray on order of L.A. Among the first, about 1906, were the portraits of Doctor Frank Loring and Mr. Hugh Legare, which were seen by L.A. and suggested the collection.”[107] Many of the portraits represent their sitters in urban business suits with hats and walking sticks; however, several of them depict their subjects in riding or hunting attire suitable for a country gentleman, and in one of them the subject appears as a chef. Although family photographs and heirlooms like those displayed throughout this room might not seem that unusual in a domestic interior, these caricatures have a more eccentric character and seem to reinforce the clubby atmosphere associated with a Billiard Room while contributing to its eclectic and ecclesiastical aesthetic, as discussed in the article that accompanies this digital component.

The whereabouts of the set of Japanese lacquerware is unknown, and there unfortunately are no detailed or color images of it. In the inventory of 1911, it was described as “Japanese black lacquered tin set with gold lacquer decoration of typical figure scenes,” and Larz added a notation in his own hand: “This very interesting and complete set of lacquer on metal acquired from Koopman (abt 1906) probably English or Dutch Chinoiserie.”[104] There also is a note in graphite in Isabel’s hand: “sent to Weld – Brookline,” indicating that it may have been moved to Brookline after the house was gifted to the Society of the Cincinnati in the late 1930s.[105]

Installed in the southwest corner of the Billiard Room near the Native American pottery was a carved teakwood, Shvetambara Jain household shrine (ghar derasar).[98] The woodwork frame, seen here, would have been separated from its icon(s) and been deconsecrated prior to its arriving in the hands of the major dealer of Indian art and antiques, Watson and Company in Bombay (now Mumbai), where the Andersons purchased it during their wedding journey in 1899. In addition, to suit Anglo-European and US tastes in that era, the frame was stripped of its brightly colored paint, though traces remain across its surface.[99] Placed in the corner against the wall on a pedestal like a piece of sculpture, this shrine, like the Native American pottery, was divorced from its original function. It became part of the Andersons’ eclectic collection, serving as a souvenir of their trip to India. In a letter to his mother, Larz associated the wood carving on the two shrines they acquired with their visit to see the “exquisite work in marble” on the Dilwara Jain temples not far from Mount Abu.[100]

Larz’s annotation in the inventory of 1911 suggests that he was particularly proud of this Jain household shrine, now located in the Great Stairs Hall at Anderson House, partly due to its rarity: “With other specimen at ‘Weld’ [the Andersons’ Brookline home][,] probably unique in America.”[101] However, he misunderstood its symbolism, as revealed by the description of the iconography in the inventory, along with Larz’s comments about it.[102] Rather than Vishnu or Buddha with elephants and nautch (court) dancers, it features a Gajalakshmi scene with elephants at the top of the universe bathing Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of wealth, fertility, and prosperity, who, in turn, holds lotuses with elephants on top of them and is surrounded by a trailing vine that emerges from the mouths of two sea creatures (makaras). The Jains, who were merchants, regarded this subject as particularly meaningful and auspicious: according to the Indologist John Cort, Lakshmi “is essentially the occupational deity of the Jains.”[103] This scene frequently appears on household shrines and temples along with the door guardians (dvarapala) at the bottom of the four pillars and the “faces of glory” (kirtimurka) along the lower edge just below the door with the rosette pattern.

The display cabinet, now in use in a library office of the Society of the Cincinnati, measures 86 in. (218 cm) wide, 50 in. (127 cm) high, and 22 1/2 in. (57 cm) deep, with 17 in. (43 cm)–deep shelves in the center suitable for the Andersons’ collection of pottery from the Southwest and 15 in. (38 cm)–deep shelves on the sides. The Andersons removed the shelves so that they could stack the pots in the central section of the cabinet. The cabinet resembles the glass cases used for displays in natural history and anthropological museums, art museums, department stores, and at world’s fairs; however, its carved wood details, including the Ionic columns, the festoon of roses in the center of the frieze, and the rosettes on the glass doors, are more elaborate than those on many such cases and harmonize with the other wood decoration on the furnishings and the walls of the Billiard Room. For the Andersons and their guests, many of whom may have been unfamiliar with Southwest pottery, the cabinet lent a preciousness and an aesthetic value to these objects, linking them to the other decorative items in the room.

This Hopi jar with its feather and wing motifs is attributed to the renowned Hopi-Tewa potter Nampeyo (1859–1942) or her daughter Annie Healing Nampeyo (1884–1968) and once belonged to the Andersons, though there is no archival evidence that they were aware of the identity of its maker. It appears in Frances Benjamin Johnston’s photograph stacked on top of another Hopi pot with strapping, and was used as a container for holding the signal (a triangular red flag with a jumping black horse) for the Andersons’ houseboat, the S. S. Roxana, another example of how the Native objects were appropriated and repurposed by their elite white owners.

This Zuni k’yabokya de’ele (water jar) with a heart-line deer motif by a maker once known, previously belonged to the Andersons. It is described in detail at the beginning of the article that accompanies this digital component. Given that formal harmony and balance were important considerations in interior decoration during the Andersons’ period, it is not surprising that the colors of the pots in the Andersons’ collection—red, ochre, black, and white—would have harmonized with the brown oak wall panels, the inlaid oak floor, and the carved walnut furnishings throughout the room, and the reddish earth tones would have complemented the green cover of the billiard or pool table and “the green plaited silk” shades on the light fixtures nearby.[97] In addition, the natural motifs painted on their surfaces, like the deer and the birds on this jar, would have been in concert with the patterns and designs derived from nature—ranging from animals to flowers to leaves—on the carved furnishings, the upholstery, the lacquerware, and the Jain household shrine.

This floor plan of the Billiard Room indicates the careful placement of the Andersons’ collection of Native American pottery along the west side of the house across from the door to the Saloon so that it would have been visible before entering the space and would have assumed a prominent position in the room. The Andersons also carefully arranged the room so that an almost triangular sightline was created among the pots, the Japanese lacquerware, and the Jain household shrine, all objects that authenticated the Andersons’ worldwide travels and their interest in what they regarded as exotic cultures.

Notes

[1] Isabel Anderson, “Home Journal, 1909,” p. 62, box 11, The Larz and Isabel Anderson Collection (1895–1948), Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center, Boston University, Boston, MA.

[2] These details come from the original blueprints for Anderson House prepared by Little and Browne in 1902. Anderson Collection, Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

[3] Larz Anderson’s Letters and Journals of a Diplomat contains more than two dozen references to “tiffin.” Isabel Anderson, ed., Larz Anderson: Letters and Journals of a Diplomat (New York, London, and Edinburgh: Fleming H. Revell, 1940).

[4] On Belton House, see Adrian Tinniswood, Belton House, Lincolnshire (London: National Trust, 1992). The similarities between Anderson House and Belton House are so marked that the latter could have been a historical source for it. The exterior façade, basic floorplans, and interior décor of some of the main public rooms of Anderson House seem to have been inspired at some level by Belton House, though there is no documentary evidence to support this observation, only the evidence that comes from the buildings themselves.

[5] See Jean-Marie Pérouse de Montclos, ed., Le Guide du patrimoine: Paris (Paris: Hachette, 1994), 277.

[6] For a discussion of Japonisme in Boston, see Victoria Weston, “‘Wonderland of the World’: The Andersons and Japan,” in Eaglemania: Collecting Japanese Art in Gilded Age America, ed. Victoria Weston, exh. cat. (Boston: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 2019), 10.

[7] Undated Town Topics clipping (before 1911), MSS L1938D11 [box 2], file NN18, Indian Purchases, Anderson Collection, Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

[8] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House, Washington City” (with annotations), 1911, p. 2, MSS L1938D1 M, Anderson Collection, Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

[9] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 3.

[10] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 4.

[11] Larz Anderson, Schematic drawing identifying the emblems, crests, and family members referenced in the ceiling and frieze of the Choir Stall Room, Anderson House, Washington, DC, ca. 1920, reproduced in Self-Guided Tour Book: The Society of the Cincinnati Museum at Anderson House (Washington, DC: Society of the Cincinnati, [1996]), [5].

[12] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 4.

[13] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 4.

[14] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 6.

[15] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 8.

[16] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 11.

[17] Larz Anderson, Some Scraps [Journals, 1888–1936], vol. 17, An Embassy to Japan. Across Siberia and through Korea to Happy Days and Associations in Tokyo [1912–13], pp. 10–12, MSS L2004G19.16, Anderson Collection, Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

[18] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 9.

[19] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 12.

[20] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 12.

[21] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 12.

[22] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 11.

[23] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 12.

[24] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 8.

[25] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 11.

[26] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 7.

[27] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 11.

[28] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 12.

[29] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 12.

[30] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 12.

[31] William Walton, “The Recent Mural Decorations of H. Siddons Mowbray,” Harper’s Magazine, April 1911, 724–35; and Stephanie Wiles, “The American Muralist H. Siddons Mowbray and His Drawing for the Larz Anderson House,” Master Drawings 31, no. 1 (Spring 1993): 21–34.

[32] In the mural, the female representing the South grasps the hilt of a sword in her bare hand. The sword is pointed downward, perhaps as a symbol of defeat and surrender. This symbolism also appears in the US artist John Trumbull’s (1756–1843) painting Surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga, New York, October 17th, 1777, in which Burgoyne presents his sword to George Washington in a similar fashion. The Trumbull painting is installed in the rotunda of the US Capitol in Washington and would have been well known to both Larz and Mowbray.

[33] “Restoring the Key Room Murals at Anderson House: An Appeal for Your Support,” booklet (Washington, DC: Society of the Cincinnati, n.d.), 4.

[34] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 93.

[35] Shari M. Huhndorf, Going Native: Indians in the American Cultural Imagination (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001), 52.

[36] This discussion of the mural is based on Larz’s account in the 1911 inventory. See Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 90.

[37] Weston, “‘Wonderland of the World,’” 8.

[38] Leslie A. Hyam (appraiser), American Art Association, Anderson Galleries, “Inventory and Appraisal of the Art, Literary and Other Property Contained in the Residence[,] Garage, Stables and Garden at 2118 Massachusetts Avenue[,] Washington, D.C.: Belonging to the Estate of the Honorable Larz Anderson,” 1937, p. 50, MSS L1938D3.1, Anderson Collection, Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, DC.

[39] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 95.

[40] Isabel Anderson, The Spell of Japan (Boston: Page, 1914), 298.

[41] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 90. The full description is: “An Allegorical figure represents War bursting forth, while the South tends her sword and the Republic seeks to restrain her.”

[42] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 98.

[43] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 90.

[44] The green satin damask wall covering is mentioned in the 1911 inventory, and the tapestries are included in both the 1911 and 1937 inventories though they are misidentified as Gambaud set rather than Gambara Series in the 1911 inventory. Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 156 (wall covering) and 162 (tapestries); and Hyam, “Inventory and Appraisal of the Art, Literary and Other Property,” 46.

[45] For dates and descriptions of the two sets of tapestries the Andersons acquired from Charles Ffoulke, see The Ffoulke Collection of Tapestries, Arranged by Charles M. Ffoulke (New York: privately printed by Frederic Fairchild Sherman, 1913), 79–87 (Diana Series) and 97–99 (Arbor Series), available on Internet Archive. For a discussion of Ffoulke’s and Larz Anderson’s relationship and their correspondence, see Denise M. Budd, “Charles Mather Ffoulke and Larz Anderson: Dealing and Collecting Tapestries in the Gilded Age,” in Collecting Early Modern Art (1400–1800) in the U.S. South, ed. Lisandra Estevez (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2021), 1–22.

[46] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 157–58.

[47] For a list of “art objects” in the French Room, see Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 164–70.

[48] Hyam, “Inventory and Appraisal of the Art, Literary and Other Property,” 45–46.

[49] Hyam, “Inventory and Appraisal of the Art, Literary and Other Property,” 47–50.

[50] Hyam, “Inventory and Appraisal of the Art, Literary and Other Property,” 46.

[51] The words come from Isabel Anderson’s poem “The Sun Goes Down (at Weld),” in Near and Far (Boston: Bruce Humphries, 1947), 70.

[52] See Richard G. Kenworthy, “Bringing the World to Brookline: The Gardens of Larz and Isabel Anderson,” Journal of Garden History 11, no. 4 (1991): 224–41; and Peter Del Tredici, “From Temple to Terrace: The Remarkable Journey of the Oldest Bonsai in America,” Arnoldia 64, nos. 2–3 (2006): 2–30.

[53] The seven paintings in the English Room are: School of Sir Joshua Reynolds (English, late eighteenth century), Lady Cockburn and Her Children (n.d.); attributed to Sir Thomas Lawrence (English, 1769–1830), Portrait of Lady Browning; Sir Peter Lely (Flemish, 1618–1680), Portrait of Anne Brudenell, Countess of Shrewsbury; attributed to School of Sir Thomas Lawrence (English, late eighteenth century–early nineteenth century), Duke of Wellington (n.d.); John Hoppner (English, 1758–1810), Portrait of Miss Kelvin; attributed to Sir Henry Raeburn (English, 1756–1823), Portrait of the Countess Dundonald (n.d.); and John Crome Sr. (English, 1766–1831), Cottage by a River (n.d.). An eighth, non-English painting also was hung there: Oswald Achenbach (German, 1827–1903), The Old Mill—Holland (n.d.).

[54] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 172.

[55] Larz Anderson, “An Inventory of Articles in Anderson House,” 173.