Practicing Art HistoryFarewell to Russian Art: On Resistance, Complicity, and Decolonization in a Time of War

by Allison Leigh

Allison Leigh

University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA

Email the author: allison.leigh[at]louisiana.edu

Citation: Allison Leigh, “Farewell to Russian Art: On Resistance, Complicity, and Decolonization in a Time of War,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 21, no. 3 (Autumn 2022), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2022.21.3.7.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

On March 3, 2022, Artnet News published an op-ed by two writers from Kyiv. It was penned less than a week after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and in the immediate wake of the ballistic missile attack near Babyn Yar, which killed at least five people. In it, the authors stated unequivocally: “Any support you provide to Russian culture right now is support taken away from Ukrainians.” According to the authors, this meant the way forward was clear: “To truly support Ukraine requires a complete boycott of Russia and a severing of international cultural collaboration.”[1]

Reading those lines, I felt like I was standing at a crossroads. As an art historian who specializes in Russian art, I had spent the previous week thinking constantly of my friends and colleagues across Eastern Europe. I, like so many in those first days and weeks of the war, was glued to news reports and social media, trying to make sense of this unprovoked and, in many ways, unfathomable invasion of a sovereign nation. The more I watched, the more devastated I became at the sight of such profound suffering, but I also realized that I now had some serious decisions to make. My first book, Picturing Russia’s Men: Masculinity and Modernity in 19th-Century Painting, had been out for a little over a year. But I was finishing a coedited volume on Russian Orientalism, and it seemed like everywhere I turned there were urgent calls to boycott Russia.[2] What is more, they were emerging in various sectors of the art world.

The day before the Artnet op-ed came out, the New York Post ran a piece about art collectors calling for the boycott of a sale that was soon to be held at the Russian-owned Phillips auction house. “Anyone involved in this auction has blood on their hands,” said one outraged art consultant. “The art world is delusional if it feels it can escape it,” said another retired hedge-fund manager.[3] A week later, I saw an announcement that the Cardiff Philharmonic Orchestra had canceled a performance of Tchaikovsky’s symphonies, describing its planned program of the nineteenth-century Russian composer’s music as “inappropriate at this time.”[4]

As I read all these news pieces, my heart sank. I have spent the last twenty years studying Russian culture, first by painstakingly learning the language and writing a dissertation about Russian art in the nineteenth century, and subsequently by producing articles and books I hoped would introduce readers to the astoundingly rich body of work that was made there. Suddenly, this work seemed impossible. Or perhaps not impossible, but potentially immoral. Everywhere I looked I was faced with the devastation Vladimir Putin was inflicting on Ukraine—from images of families hunkered in subway stations in Kharkiv (fig. 1) to newborn infants moved into bomb shelters in Dnipro.

In those devastating first days of the war, when so many of us were confronting a mix of shock and helplessness, I kept thinking about a novel by Nikolai Chernyshevsky (1828–89), first published in novel form in St. Petersburg in 1863. Its title in Russian is Chto delat’? (What Is to Be Done?) (fig. 2). I could picture those words on the spine of the English translation I kept in my office. And the question began to ring like a refrain in my mind every time I thought about all the lives being upended by Putin’s unjustified “special military operation.” What is to be done? How could I—as a specialist in the social, political, and cultural history of Russia—help counteract the imperialist narratives being advanced by Putin’s regime? In the face of the atrocities being committed, what was my responsibility as a scholar (and as a human being) now?

On the surface, the op-ed in Artnet News should probably have come as a relief. Its authors made the answer to that question abundantly clear: turn away from Russia, sever all ties. At the end of the piece, they even reproduced an open letter from the Kyiv-based Ukrainian Institute with a detailed list of actions it encouraged readers to take until Russia “completely withdraws from Ukraine and is held responsible for its war crimes.”[5] The letter outlined what solidarity with Ukraine would entail for someone in the art world: suspend any Russian participation in international exhibitions; boycott cultural events organized by government-funded Russian institutions; and cancel all cooperation with Russian artists who do not publicly oppose Putin’s regime.

Reading that list, I wondered whether such extensive and multipronged abstentions would be possible. For those who specialize in Russian art—who teach its unique history, who are currently writing dissertations or books about it, who curate the cultural artifacts that comprise it, who work to cultivate collectors for it at auction houses—would it be possible to divest themselves from the mothership in this way? And would such proscriptive actions have the effect those brave writers were intending? Would sweeping boycotts help break down colonialist legacies and counteract the hegemonic dominance of Russian cultural narratives in Eastern Europe?

It may seem like these kinds of questions have little to do with the field of art history more broadly or the history of nineteenth-century art to which journals like this one are devoted. But for a moment, consider the effect such embargos would have on your own art historical practice if they were imposed on your area of expertise. How would your work need to change if you were confronted with a sudden moral obligation to boycott completely your participation in or visitation of, say, French exhibitions? How would you respond if you were unexpectedly compelled to refuse funding from any British organizations that receive government funds? How would your teaching, research, or curation plans change if you could no longer work with any artist who refused to publicly denounce, for instance, President Biden?

Or, to extrapolate about some of the realities a bit further, what if securing the rights to reproduce images from the museums on which you depend was swiftly made impossible? What if you were faced with the possibility that you could never again visit the place where the art you study is held? This is the future that my colleagues and I now face. In the six months since the war first began, anyone and everyone who works on Russian art—graduate students writing dissertations, curators organizing exhibitions, and tenure-track (or underemployed) professors striving to finish books—has experienced sudden and unprecedented changes to how we do our work. In what follows I outline some of these changes and trace the emerging ethical dilemmas that accompany them. Each section begins with an episode or experience—a headline, a social media post, a museum announcement, or a call for papers—that served as a catalyst for my own exploration of these evolving obligations. I use these occurrences to investigate the larger range of responsibilities that art historians now face.

Without a doubt, there is no comparison between the kind of professional setbacks that Slavicists are encountering and the nightmarish reality facing the soldiers who are defending cities in Ukraine or all those who have been forced to flee their native land. Each of us, in our unique capacities, should consider how we can help those who are suffering because of the war, and act accordingly. For many, this might mean donating money or supplies to relief organizations. But for anyone involved in the study, exhibition, or sale of Russian art, this will not be enough. We must deeply interrogate how we have been involved in the creation of imperialist myths, and consider what part we play in undermining distinctive Ukrainian cultural narratives. For me, this has meant taking immediate action in those areas where I can—from submitting an op-ed on Russian propaganda to the New York Times to overhauling a seminar I teach on Russian art so that it now includes an equal amount of Ukrainian art.[6]

While this article is another of my efforts, it is also distinct from them, seeking to explore the radical transformations now necessary within the field of Russian art history. While these changes must occur, they cannot and should not minimize the fraught nature of continuing to write about Russia at all. For Ukraine, for its citizens, for its art and its culture, the stakes could not be higher. What Ukraine is now bravely facing down is a form of cultural and political annihilation that makes the death of the field of Russian art history pale in comparison. I hope my readers will keep this in mind as I consider the range of ethical impasses now emerging because of the war—all of which are rarely considered when we think about what it means to practice art history.

Resistance

On February 28, 2022, just four days after Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine, the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, one of the most important museums devoted to Russian art in the world, posted a photograph of a painting to its official Instagram account (fig. 3).[7] The canvas, titled The Apotheosis of War: To All Great Conquerors, Past, Present and Future, was painted by the Russian artist Vasily Vereshchagin (1842–1904) in 1871, at the height of Russia’s colonializing campaigns in Central Asia. Many saw the post as a subtle denunciation of Putin’s attack on Ukraine just a few days earlier. The caption beneath the photograph solidified that impression. It read, in Russian:

These days, we, like everyone else, are closely and anxiously following the ongoing events that cannot leave anyone indifferent. We believe that culture is designed to unite people, give hope, form a space for dialogue, and promote mutual understanding. The museum remains open; we are adjusting our plans and continue to work for you, upholding humanistic values.[8]

It was a brave move, one that clued me in to something very important in the earliest days of the war: not everyone in Russia supports the actions of Putin and his regime. It served as evidence that many may be cautiously trying to telegraph their opposition, despite the serious potential repercussions.

Admittedly, such a post would not be possible today. In fact, I am surprised it remains up on the account, given that only a few weeks later Russia’s parliament unanimously voted to adopt amendments that criminalized all criticism of the government’s actions abroad. Such disparagement now carries steep penalties, including up to fifteen years in prison, and there are signs the law is being applied retroactively in order to charge anyone whose social media posts are perceived as “extremist,” even if they date from years earlier.[9]

Those terrifying amendments and the post itself led me to think about all the curators, researchers, librarians, and image custodians I know at the State Tretyakov Gallery. I had been interacting with many of them over the previous months because the museum was organizing the publication of a collection of essays stemming from a conference that took place at the Tretyakov in May of 2021. The conference commemorated the 150th anniversary of the foundation of The Partnership of Traveling Art Exhibitions (Tovarishchestvo peredvizhnykh khudozhestvennykh vystavok). This group, more well known in the West as the Wanderers (Peredvizhniki), organized shows that brought Russian art to cities throughout the empire beginning in 1871. I was honored to speak at the conference and to further establish relationships at the Tretyakov, where most of the nineteenth-century paintings I write about and teach are held. I was also thrilled when the researchers and other staff at the Tretyakov invited me to submit the paper I had originally presented for inclusion in the volume of essays. In fact, I had only just sent it to them in mid-January, a month before the war began.[10]

Now I wonder if the publication will ever see the light of day. If it does, it will be interesting to see whether it includes the contributions of all the Western scholars who participated in the conference. There are many signs that such collaborative, international cooperation is no longer possible, despite the hopes of the curators at the Tretyakov and whatever their intentions may once have been. All sorts of bans, withdrawals, and directives have been issued in recent months by a range of institutions and government authorities on both sides of the Atlantic.

In early March, the Hermitage Foundation UK, which had assisted the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg with fundraising since 2003, halted all its efforts at “building cultural bridges between the UK and Russia.”[11] Later that month, the Russian government barred its researchers from participating in international conferences. This was followed by the Russian Ministry of Science and Higher Education’s announcement that it would stop indexing Russian scientists’ publications in international databases.[12] In May, Russia “officially withdrew from a memorandum of understanding with the U.S. in the field of culture, education, and the media.” Soon after, the American Smithsonian Institution circulated a letter directing “employees and affiliated persons” to wrap up “all direct communications and collaborative work, research, programmes or projects with Russian government-affiliated counterparts.” The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York then issued a statement condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, stating further that “MoMA has suspended all activities involving the Russian Federation and its supporters until further notice.”[13]

Amid all these directives, there were a handful of voices calling for the need to maintain relationships with those in Russia who did not support the war. CEC ArtsLink, a New York-based organization founded during the Cold War to build trust between citizens of the United States and the Soviet Union, said: “It is critical that we maintain contact and engagement with independent artists from Russia and Belarus who oppose the war and stand for individual freedom, whose voices are silenced or suppressed.” Raymond Johnson, the founder of The Museum of Russian Art (TMORA) in Minneapolis, said that “if ever there was a time when the Soviet period should be studied in depth, this is it.” Other American museum directors lamented the sudden loss of relationships they had spent decades fostering. “With one big bang, everything that was built during the last thirty years is more or less destroyed,” said the newly appointed director of the Museum of Russian Icons in Clinton, Massachusetts. “The friendships, the relationships between museums, cultural relations, between people, business [have ended].”[14]

The more news I read, the more I began to wonder: should I withdraw my essay from the Tretyakov’s Peredvizhniki volume? If I was an employee of one of the Smithsonian museums (or MoMA for that matter) I might have no choice. But what would be the effect of pulling my work from the anthology? Would it show my opposition to the war and support for the Ukrainian people? Or was it merely a strange form of academic virtue-signaling that would only assuage my own guilt at having ties to the state-controlled (and government-funded) Tretyakov?

In the end, the historian in me won out. I decided not to withdraw my essay. My reasoning may seem strange, but ultimately my rationale was that retracting it would distort the historical record. An important exchange took place during that conference between Russian specialists (many of whom have devoted their careers to the study of the Peredvizhniki) and their Western counterparts. Each of us within these overarching groups brought unique perspectives to the material. I benefited tremendously from hearing the latest thinking coming out of Russia on these artists—especially because much of it was drawn from archives that I could not easily access. Likewise, I imagine that at least some of the Russian scholars found the methodologies and approaches we Westerners brought to bear on the subject illuminating.

If I pulled out of the publication then I would not only deprive all future students and researchers of this vibrant exchange but I would make it seem like it never happened. And I think that is what Putin and his cronies want. They are now actively engaged in quashing the kind of international collaboration and conversation that took place at that conference. If they have their way, there will be no more sharing of ideas between East and West—and it follows that any evidence of such recent cooperation must be disavowed.

My expertise makes me painfully aware of the long history of carefully calibrated propaganda that has been disseminated by leaders in this part of the world. In Russia, both photographs and artworks have played a particularly prominent role in manipulating the truth. Sometimes such maneuvers are fairly harmless, as when the tsars had themselves depicted in portraits looking a bit younger than they were in reality. Yet the control exercised over Russian visual culture is often more insidious, as when Leon Trotsky (1879–1940) was disappeared from photographs of Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924) in the 1920s (fig. 4) or when Stalin’s political opponents were erased from images during the purges. This long record of censorship and manipulation makes me hypervigilant about historical distortions of any kind; I will not be made even the smallest of pawns in that game.

Yet I think there are even greater lessons to be taken from this ethical dilemma about one small publication that I found myself in. Those of us engaged in the practice of art history should think more carefully and habitually about who is publishing our work. Maybe many of you already do. But before the war, I will admit that I did not regularly consider the implications of aligning myself with certain presses, editors, or host-publication countries. In the high-pressure academic world of “publish or perish” (and with my own tenure clock ticking), I was grateful whenever my work was accepted for publication. And my thoughts before submitting to certain journals or presses were mainly about the quality of the peer-review they offered or the prestige of the host societies and institutions.

But how far should such considerations be taken? For instance, China has a long history of committing human-rights violations against its citizens (which continue into the present). Should I have refrained from publishing my essay in the conference proceedings volume for the 34th World Congress of Art History, which took place in Beijing in 2016?[15] What about individual university and trade presses? If, say, one finds the psychologist Jordan Peterson’s vocal opposition to transgender rights abhorrent, should they refrain from submitting a book proposal to Random House (the press that published his wildly popular 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos)? Extrapolating further, I know that many were disappointed when the College Art Association (CAA) did not issue a statement condemning the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade (whereas CAA was quick to publicly condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine).[16] Should those individuals refrain from ever submitting their work for publication in CAA’s preeminent journal, The Art Bulletin?

These questions do not have easy answers, and, in many ways, each of us will have to draw these lines for ourselves. But this is an instance where the dilemmas currently facing those of us who work on Russian art (and routinely publish our work in the journals and books produced by Russia’s state-controlled museums) can foster a discussion about the kind of ethical considerations that are rarely discussed in our field. I made the difficult decision not to withdraw my essay from the Tretyakov’s volume because I did not want to participate in the willful historical distortions that I know the Russian authorities have been engaging in for nearly a century. But depending on what the future holds, I may make a different decision the next time I am faced with a similar situation. Right now, all I can say is that I am assessing decisions like this more carefully than ever before—and that seems like a good thing.

Complicity

On March 6, 2022, ten days after the first missiles struck in Ukraine, the online arts magazine Hyperallergic published an opinion piece that caught my eye. The headline ran: “How the Hermitage Museum Artwashes Russian Aggression.” The short summary of the piece below it was even more striking: “Collaborations with the State Hermitage Museum are particularly problematic since the director, Mikhail Piotrovsky, flaunts his bond with Putin.” The article goes on to describe the close relationship between these two men and the ways that the Hermitage Museum, under Piotrovsky’s leadership, cultivated a strategy of global expansion that feeds directly into Putin’s efforts to use Russia’s cultural patrimony to advance his political objectives.[17]

There is a lot to unpack here, but before I delve into the dilemmas I see stemming from this particular intertwining of art and politics, let me provide some basic facts about the Hermitage. The museum itself is located in St. Petersburg, the city founded on the Neva River by Tsar Peter the Great in 1703. Most of the museum’s art collection is housed in what was once the Winter Palace, which served as the grand official residence of the Russian tsars and tsarinas up until the revolution in 1917. As a result, the museum is massive. In fact, at 2,511,705 sq. ft. (233,345 sq. m), it is the largest art museum in the world—nearly four times the size of the Musée du Louvre in Paris.[18] Its collection is equally extraordinary. It includes over three million works of art and cultural artefacts from all over the world. Nearly every major artistic figure from the last five hundred years is represented in the collection—Giorgione (1477–1510), Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), Raphael (1483–1520), Titian (1488–1576), Caravaggio (1571–1610), Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), Rembrandt (1606–69), Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), Francisco de Goya (1746–1828), Antonio Canova (1757–1822), Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Claude Monet (1840–1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Vincent van Gogh (1853–90), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), to name but a few.

Because the museum is federally funded, all of this is the property of the Russian government. In 2011, the museum even became subject to new statutes which specified that the Russian government was also to act as the museum’s founder.[19] Hence the word “State,” or Gosudarstvennii, in the museum’s name—a designation which appears in all the official titles of the state-controlled museums (the State Tretyakov Gallery [Gosudarstvennaia Tretiakovskaia Galereia], the State Russian Museum [Gosudarstvennii Russkii Muzei], and so on).

This is where Putin comes in. The close relationships he maintains with Russia’s museum directors (and Piotrovsky in particular) are well documented. Piotrovsky inherited the leadership position at the Hermitage from his father in 1992 and, by all accounts, he was associated with Putin throughout the 1990s. Piotrovsky has confirmed their long-standing connection in interviews, stating that “Putin has been my person from the early ’90s” and even going so far as to admit that “he is closer to me than many others.” Their closeness certainly has been beneficial for Piotrovsky. It shielded him from facing any serious repercussions after several scandals, including accusations that he allowed friends to profit from an art-transportation company. And his son, Boris, was appointed the vice governor of St. Petersburg in early 2021.[20]

Many have expressed concerns about the direction that Piotrovsky has taken the Hermitage in the last thirty years. The museum’s activities frequently correspond with Russia’s geopolitics, as when Piotrovsky capitalized on the surge of Russian troops in Syria to lead an expedition (with a Russian military escort!) to the ancient city of Palmyra.[21] More recently, in an interview published in the government’s official newspaper, Rossiiskaya Gazeta, Piotrovsky described Russian art and culture as important “exports,” before directly comparing their dissemination to the war itself. “Our recent exhibitions abroad are just a powerful cultural offensive. If you want, a kind of ‘special operation,’ which a lot of people do not like. But we are coming. And no one can be allowed to interfere with our offensive.”[22]

Such brash sentiments are frankly terrifying. But the rhetoric does not end there. In that same interview, Piotrovsky went on to state that he believes Russia has a distinct “cultural advantage” and that the arts are a sector in which “we are winning.” In fact, for Piotrovsky, “the joy” with which individuals and organizations in the West “rushed to condemn” all things Russian after the invasion is only a sign of how “strong we are in culture.”[23]

When I read the full interview on the Rossiiskaya Gazeta website, my first thought was that, clearly, art matters to Putin.[24] I had seen him exploit his relationship with the Hermitage and its director for political maneuvers before, but never on this scale. There were often press photographs showing Putin conducting diplomatic encounters in the Hermitage with a range of world leaders—from UK Prime Minister Tony Blair and Chinese President Xi Jinping to Austria’s Federal Chancellor Sebastian Kurz (fig. 5). Now I saw these art-infused meetings with heads of state as an essential element in what Piotrovsky was describing as Russia’s “powerful cultural offensive.” The abundance of art in Russia’s state-controlled museums had long served as a mechanism for awakening dignitaries to the sheer wealth of Russia. But now it was becoming clear that Russia’s exhibitions abroad, its loans to other museums, and the partnerships that various institutions had made with the Hermitage were part of a deeper effort to disseminate an image of Russia that celebrated its imperialist past. And all this had the added benefit of making the Western art world beholden to Putin’s largesse.

Without a doubt, numerous institutions and individuals took the bait over the years. In hindsight, it is almost unfathomable how many are now implicated. If we look only at examples from the most recent past, it becomes clear how far the “cultural offensive” infiltrated. When the war began, numerous loans from government-funded Russian museums were on view in the West. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London had a show dedicated to the iconic eggs made by the Russian goldsmith Carl Fabergé (1846–1920) (fig. 6).[25] The National Gallery in London was waiting for paintings from the Hermitage for its exhibition on Raphael.[26] The State Russian Museum, which is not far from the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, had exhibitions on Fëdor Dostoevsky (1821–81) and the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893–1930) in Spain.[27] And the Hermitage had loaned some twenty-four works to Italian museums for exhibitions on Titian and Grand Tours of Italy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[28]

There was also a blockbuster show of numerous avant-garde paintings bought by the prerevolutionary Russian collectors Sergei Shchukin (1854–1936), Mikhail Morozov (1870–1903), and Ivan Morozov (1871–1921) on view at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris.[29] That exhibition featured around two hundred works by the likes of Van Gogh, Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Matisse, and Picasso, many of which were loaned by the Hermitage. Several also came from the State Tretyakov Gallery and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts.[30]

Then there were the paintings loaned by oligarchs with close ties to Putin. Those works became embroiled in the maelstrom of geopolitical shifts occurring in the weeks after the invasion of Ukraine. By the end of May, headlines appeared revealing that two works from the exhibition at the Louis Vuitton Foundation had been seized by European authorities. One, a self-portrait by the Ukrainian-born Pëtr Konchalovsky (1876–1956), was owned by the Russian oligarch Pëtr Aven, whose assets were frozen as part of sanctions against Russia. A similar fate befell a portrait of Timofei Morozov by the Russian painter Valentin Serov (1865–1911) (fig. 7). It belonged to Moshe Kantor, another oligarch with close ties to Putin.[31]

All this made me wonder: Are the art-collecting oligarchs, the Russian museums, and directors like Piotrovsky going to become the new Sacklers? That family, as a source of funding and artistic benevolence, had become very problematic for museums when the source of their estimated $13 billion fortune was revealed by journalists in 2017. After decades of taking money and art from the family, who owed most of their wealth to sales of the highly addictive prescription opioid OxyContin, the art world finally turned its back on the Sacklers—because of what they represented. The National Portrait Gallery in London turned down a promised gift of $1.3 million in 2019, and the Tate Modern in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Guggenheim Museum in New York all followed suit. Many institutions, including Tufts University and the Louvre, also removed the Sackler name from their galleries, buildings, and programs.[32] “When it comes down to it, they’ve earned this fortune at the expense of millions of people,” wrote Allen Frances, the former chair of psychiatry at Duke University. “It’s shocking how they have gotten away with it.”[33] Much of the same could be said about the way art from Russia’s collections was used for political maneuverings as well.

In the wake of the invasion, all those exhibitions which featured loans from museums controlled by Putin suddenly looked quite suspect, as did all the collaborations between Western institutions and the Hermitage specifically. Many sought to quickly divest themselves of those connections. The Hermitage Amsterdam, a privately funded satellite of the museum in St. Petersburg, officially cut ties with the latter, sending an exhibition of Russian avant-garde art that had been scheduled to run for a year back to Russia. It also quickly rebranded itself with a new series of exhibitions titled Dutch Heritage Amsterdam.[34] Plans to open a satellite of the Hermitage in Spain, which had been in development for a decade, were also quickly abandoned.[35] And some of the oligarchs began to step down from their roles as trustees of major museums.[36]

Both these cases and that of the Sacklers reveal something art historians do not often contemplate: that much of the art we study is, for lack of a better way to put it, dirty. Or maybe I should say that it has become as “dirty” as the frequently ill-begotten gains used to initially acquire it. Over the centuries, as art passes through the hands of various high-net-worth patrons and collectors and museums—whether they be corrupt Medici bankers, the drug-peddling Sacklers, or the boot-licking Piotrovskys of the world—it becomes tarnished. The history of who commissioned it, collected it, and donated it, as well as how it is now used (and for what purpose), is, as a result, embedded in the work. This often means that much of what we analyze and revere is embroiled in misdeeds, whether we choose to acknowledge that history or not.

Yet in this new age of scrutiny, I do not think we can afford to turn a blind eye to the murky underbelly that accrues to artworks or the ways that art collections are used in geopolitical games. Amid ever-increasing calls for accountability, we must think continually about how what we see on museum walls got there—and often that will mean reckoning with how art philanthropy is used to whitewash fortunes (and regimes) that have been built on human suffering.[37] Again, I think this is an instance where the war in Ukraine and the fallout surrounding long-standing relationships with the Hermitage, the oligarchs, and Russia’s state-controlled museums have much wider repercussions—and for many more individuals and institutions than just those of us who work on Russian art.

As individual researchers, professors, and writers on art and its histories, we can play an important role in counteracting the kind of “cultural offensives” that Putin and Piotrovsky have been engaged in. It will require us to be vigilant about how the scholarship we produce and teach might be contributing to the perpetuation of deep-rooted myths of cultural “greatness.” And we will need to transparently acknowledge the ways that artworks have been used as mechanisms for coercion, persecution, and sometimes real cruelty. For the reality is, virtually every major Western nation has, at one time or another, engaged in the kind of imperialist and colonialist atrocities that Russia is currently committing. Anyone who works on British art between the sixteenth and the nineteenth century (or French art or Dutch art or Spanish art, for that matter) is engaged with, at least peripherally, a history of oppression and exploitation, even if it does not directly bear on their work. This is sometimes a bitter pill to swallow, but it is already becoming a more important part of the field.

Lastly, there are some microlevel considerations that I, at least, had not often examined when going about my work before the war broke out. These may seem simpler than the factors I was just describing, but they are no less important. The next time you find yourself writing on an artwork, knowing you will need to buy the rights to reproduce it—pause and ask yourself: Who will you have to pay for those rights (and perhaps for the high-resolution photographic file itself)? How might such a payment align your work with larger political agendas?

In preparation for writing this piece, I went through all of my past contracts with Russian museums and discovered, much to my relief, that I have never paid the Hermitage for rights to reproduce any of the artworks in its collection. It was one of the museums that always generously granted me clearance (and provided beautiful high-resolution TIFFs) free of charge. But I now shudder to think of the thousands of dollars I have paid to other government-funded institutions in Russia, including the State Tretyakov Gallery and the State Russian Museum. I want to believe that when I sent wire transfers to those institutions, the money was not directly funding Putin’s agenda. Surely the museums use whatever funds are generated from reproduction rights to fund their own exhibitions or restoration projects, or to hire more curators. But I do not think I can afford to be so naïve anymore.

And this is not a quandary facing only a few outlying Russian art specialists. Because the Hermitage has such a vast collection, if it is not as generous in granting gratis reproduction rights in the future, many who work on more canonical artists may find themselves in dire circumstances when it comes to illustrations for their publications. For now, we are all off the hook. The bans on SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications) payments to Russia that went into effect, along with numerous other economic sanctions against Russia, make it impossible to pay for any images or reproduction rights from Russian museums.[38] But this creates a whole subset of new problems in terms of how to go about finding reproductions of artworks that are now completely inaccessible.[39]

This is the future—fraught with dilemmas—which we now collectively face. Some of these predicaments are not new; some have existed for a while (though we may have managed to disregard them). But others really are or will be new, and my hope is that reckoning with them might allow us to see how our research can become embroiled in processes of corruption—and resist ever being made complicit in such “cultural offensives” again.

Disinformation

On April 3, 2022, thirty-eight days after the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, The Guardian published a story about the National Gallery in London altering the title of one of the pastels by Degas in its collection (fig. 8). The work, long titled Russian Dancers, was renamed Ukrainian Dancers after many members of the general public called for the change on social media. They claimed that the yellow and blue found in the hair ribbons and garlands of Degas’s dancers plainly indicated Ukraine’s national colors, and as such made it clear that the women in the pastel were Ukrainian, not Russian. According to a spokesperson for the museum, the title of the work had been “an ongoing point of discussion for many years,” but the war had brought an “increased focus” that made it feel like “an appropriate moment to update the painting’s title to better reflect the subject of the painting.” After the change was announced, the National Gallery declared that it would remain “very open to receiving feedback from the public about specific works,” including via social media, and that efforts were underway to respond regularly to comments shared by audiences.[40]

Many celebrated the renaming and hoped that it would spur other cultural institutions to rethink labels that perpetuated the loss of Ukraine’s unique cultural heritage. Olesya Khromeychuk, the director of the Ukrainian Institute in London, was among those voices. “Every trip to a gallery or museum in London,” she wrote, “reveals deliberate or just lazy misinterpretation of the region as one endless Russia; much like the current president of the Russian Federation would like to see it.” The Ukrainian-born founder of an art-advising service called Art Unit, Mariia Kashchenko, agreed. “I understand that the term Russian art became an easy umbrella term which was useful but it’s really important now to get things right.”[41]

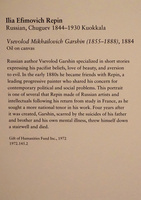

When I first saw the news, I was thrilled. I had long been troubled by exactly what Khromeychuk and Kashchenko were describing—this knee jerk tendency to label all artists who hailed from various parts of the former Russian empire (and then also the USSR) as “Russian.” In the past, when I had written on some of the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artists who hailed from Ukraine (or had Ukrainian heritage), I had felt torn about how to describe them. Two figures in particular gave me pause whenever I wrote about them or taught their work—Illia Repin (1843–1930) and Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935). Both of these painters are routinely described as Russian on museum wall labels, in textbooks, in news articles, and even sometimes in scholarly writing. But their origins and ethnic heritage are more complicated than those facile designations make it seem.

Repin, for instance, is frequently cast as one of the most important Russian artists of the nineteenth century, a sort of father figure whose works are seen as anticipating the great masterpieces of the Russian avant-garde. But he was actually born in the town of Chuguev, just east of the modern-day city of Kharkiv, in a part of the Russian Empire then called Sloboda Ukraine. He came from a family of military colonists and spent his childhood visiting local fairs, watching Orthodox religious processions, and speaking Ukrainian. In fact, even his very first attempts at painting were devoted to a form of craft specifically associated with Ukrainian culture: decorating Easter eggs known as pysanky with intricate patterns. He ultimately moved to St. Petersburg in 1863 to study at the Imperial Academy of Arts, but as Thomas Prymak has written, “he never completely forgot his southern roots, occasionally turning to Ukrainian themes in his work [fig. 9] and maintaining contacts with prominent Ukrainians to his very death in Finnish exile in 1930.”[42] By the middle of the twentieth century, however, Soviet art historians were regularly avoiding discussion of these works, as well as any mention of Repin’s Ukrainian roots. Instead, he was consistently portrayed as one of the great heroes of Russian art and an important pioneer in what would ultimately become the official style of socialist realism.[43]

Such opacity concerning Repin’s heritage continues well into the present. One need look no further than the differences between the Russian and English versions of the artist’s Wikipedia page. In the Russian account, he is described from the very beginning as a “Russian painter” and his birthplace is given as “Chuguev, Russian empire.” In the remainder of the very lengthy account of his life and works, there is only one sentence that mentions “Ukrainian motifs” in the artist’s paintings, before noting that he tried “to maintain connection with his native city and Sloboda Ukraine.”[44]

The English Wikipedia entry for the painter, on the other hand, immediately gives both the Russian (Il’ya/Илья) and Ukrainian (Illia/Ілля) transliterations of Repin’s name, and then describes him more judiciously as “a Russian painter, born in what is now Ukraine.” An even more thorough account of his origins, stating that he was born “in the town of Chuguyev, in the Kharkov Governorate of the Russian Empire, in the heart of the historical region of Sloboda Ukraine” then follows. There is also a section later in the entry specifically devoted to “Repin and Ukraine,” which has a list of his paintings inspired by Ukrainian culture as well as a description of his relationships with artist unions and art schools in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Odesa.[45]

Such discrepancies and evasions are also common in discussions of perhaps the most famous of all “Russian” artists: Kazimir Malevich. He was born to Polish-speaking parents in the city of Kyiv in 1878, but these ethnic roots are routinely minimized in favor of narratives that posit him as the great Russian progenitor of the Suprematist style of abstract painting.[46] Most scholars are quite careful in how they describe him, quickly nodding, in different ways, to the intersecting Ukrainian-Polish-Russian elements in his ethnic and biographical background. Piotr Piotrowski refers to Malevich as a “Russian-Ukrainian of a Polish background,” while Charlotte Douglas notes that he was “born in Ukraine, [but] did his principal and best-known work in Russia.”[47]

If you search for Malevich in museum collections and databases, however, you will often see him listed as Russian or as some other rather garbled conglomeration of nationalities that begs for firmer explanation. The Buffalo AKG Art Museum (formerly the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York) falls into the former category, designating him simply as “Russian” (fig. 10), while the Yale University Art Gallery and MoMA list him as “Russian (Ukraine)” (fig. 11) and “Russian, born Ukraine,” respectively.[48]

Using this logic, one would expect to find other artists who hailed from one country but worked most of their lives in another described similarly on museum websites. Yet that is simply not the case. Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) is never listed as “French (America),” despite the fact that she was born in Pennsylvania and spent most of her life working in Paris. And Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) is never described as “Italian, born France,” though that would be an accurate parallel for labeling Malevich as “Russian, born Ukraine,” given that Ingres was born in Montauban, France, and spent the largest portion of his career in Rome.

So why do we find it so difficult to get it right when it comes to describing artists who hail from Ukraine, like Malevich and Repin? Why are more Western museums not making greater efforts to accurately portray the ethnic backgrounds of these and other Ukrainian artists given how important these distinctions have now become?[49]

When I first saw that the National Gallery in London was making changes to its wall texts and labels based on national distinctions (and being more sensitive to the differences between Ukrainians and Russians specifically), I thought we would soon see sweeping efforts to draw a finer line between ethnicities. I began routinely keeping an eye on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s website in particular, for that museum has three paintings and one drawing by Repin in its collection. I knew he had long been designated as Russian on both its website and the wall labels next to his paintings in the galleries (fig. 12). So, I began routinely checking to see if the designation would change in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The first time I looked it, at the very beginning of May, Repin was still listed as Russian on the website. When I checked three months later, while writing this article, it had not changed (fig. 13).

This distinction may seem like a small thing, but I want to make the case that it matters—a lot. And, much like the problems that stem from a lack of transparency and ethical awareness I described in the previous section, it is ultimately a matter of complicity. If those who work in museums and those who write about the art of the former Russian Empire fail to make these kinds of ethnic and cultural distinctions, they and we become guilty of perpetuating the precise mythology that Putin is using to justify the war. The successful co-optation of Ukraine depends on Putin’s claim that its culture, its people, its land, and its art are coterminous with Russia itself. But nothing could be further from the truth. And part of unraveling and counteracting this toxic ideological narrative will be recognizing—repeatedly and in every possible instance—distinctions among the nationalities of artists who hail from the region.

Speaking of transparency, it is probably time for me to admit that I have fallen short in this regard. It pains me to say it, but in preparation for this article, I went through all of my own publications to see how I had labeled Repin and Malevich—and whether I had ever succeeded in doing justice to their Ukrainian heritage. According to the standards to which I now hold myself, I did not. In the single article I published on Malevich, in 2019, I repeatedly referred to him as a “Russian” painter, and I never mentioned his birth in Kyiv or his Polish heritage.[50] I did only marginally better in an article I wrote on Repin’s interactions with French modernism later in the year. In that piece, I added a footnote to my first characterization of Repin as a Russian artist, explaining that he had, in fact, been born in Ukraine.[51] But then I immediately undermined that fact to justify my own description of him as Russian by quoting from a letter in which he portrayed himself that way in 1894.[52]

I also know that I have repeatedly called both Malevich and Repin Russian in the classroom. In general survey courses and even in more specialized seminars on Russian and Soviet art, I almost always simply describe them as Russian. In part, this is because they are characterized as such in the textbooks I use for those courses.[53] But really, that is not an excuse. It would be easy to add more nuance to my discussions of the major figures that hail from different parts of Eastern Europe.

Now I see my failure in this regard as a grave mistake, but one that is also slightly fascinating in the grander scheme of things, for it does not appear elsewhere in my art historical practice. I do not, for instance, call Picasso a French artist, despite the fact that he spent most of his career in France, was in dialogue with the leading figures of French culture, and has become an important part of the history of French art. These factors, albeit in the Russian context, are regularly used to justify calling Repin or Malevich Russian, but such distortions do not typically occur in the more firmly Western context. So, if Picasso can retain his Spanish origins despite his lifelong ties to France (much like Cassatt and Ingres retain theirs), then we should be able to properly account for Repin’s and Malevich’s heritage as well.

The work does not end there, however. If we really want to counteract Putin’s grandiose “Russia-is-everywhere-and-everything” rhetoric, then we must also vigorously counteract the dominant Russophilic transliterations of Ukrainian names and places. This has already begun to happen. You may have noticed it in the case of Kyiv (Київ)—Ukraine’s capital city—which until recently was often spelled by transliterating it from Russian (Kiev/Киев).[54] What you may not realize is just how important these distinctions are in terms of counteracting the dominance of the Russian language within Ukrainian culture. There are numerous other instances where the Ukrainian transliterations of place names carry significant weight, and I wish I was seeing more academic journals, university presses, and scholarly organizations add these spellings to their style guidelines for submissions. Many of the distinctions are quite subtle (Odesa instead of Odessa, Kharkiv instead of Kharkov, Serhiy instead of Sergei) and many of them might be challenging for those who are not familiar with Eastern European languages, but these distinctions now have an ideological weight that we cannot afford to ignore.[55]

Continuing to publish the Russian spellings of Ukrainian names and places, much like continuing to accept loans from those state-controlled museums (or funding from Putin’s oligarch buddies), sends a profound message. And, in this moment, we must do all we can to amplify the differences and distinctions between Russian and Ukrainian culture—to counteract every element of destruction that is being carried out by Putin and his armies. In the world Putin seeks to create, all Ukrainian artists are just Russian artists in disguise. And all those other spellings of cities and names are simply signs of the kind of “Nazification” that he uses to justify his invasion in the first place.[56]

Disinformation is the game here, and it is part and parcel of a much larger form of destruction that art historians have a responsibility to neutralize with every tool at our disposal. In this case, our weapons will be our writing, our classrooms, and our wall texts, and our ammunition will be names and nationalities and titles and origins and places. We can play a part in counteracting the forms of annihilation currently being wrought on Ukraine and its vital heritage—though it will sometimes require doing extra research or admitting where we have failed in the past. Looking back on my own work, I can now clearly see how I fell prey to the kind of imperialist narratives which surround Ukrainian artists like Repin and Malevich. I will not make that mistake again.

Decolonization

On July 29, 2022, five months and five days into the war, I saw a call for submissions for a new edited volume titled Towards Decolonizing Eastern European and Eurasian Art and Material Culture: From the 1800s to the Present. The description had a powerful opening line: “The world changed forever on February 24, 2022, when the Russian Federation invaded Ukraine.”[57] The authors then outlined the stakes of the project, citing an urgent need to reassess Slavic studies, to develop approaches that illuminate Russian colonialist narratives, and to deconstruct the imperialist history that laid the foundation for Russia’s aggressive geopolitics. Next they outlined the major points in Russia’s unfolding history of expansionist endeavors—from Peter the Great’s building of a new capital on the Swedish lands he gained in the Great Northern War (1700–21) to Catherine the Great’s annexation of Crimea in 1783 to the colonization of the Caucasus and Central Asia in the second half of the nineteenth century to the Soviets’ imposition of the Russian language throughout the USSR in the 1930s.

Reading through the full description, I began to feel a spark of hope about the future of my field. I had seen a similar call for papers earlier in the summer, but now the demands for reassessment seemed to be growing in urgency and momentum. The earlier call, which was issued by the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES)—the leading organization dedicated to the advancement of knowledge about the region—had been limited to decolonizing efforts in the realms of teaching and alterations to curricula.[58] But together, both calls for papers revealed a field that was becoming more introspective and self-critical than I had ever known it to be in the past.

These forms of engagement appeared to be infusing numerous sectors within Slavic and Russian studies as well. On the same day that ASEEES sent out the call for submissions on the subject of decolonizing undergraduate teaching and graduate training, a message from the organization’s board of directors also appeared in my inbox. It condemned “the lies the Russian government is using to justify its invasion” and called on members to support the people of Ukraine by “offering what support we can to those whose livelihoods and lives hang in the balance.” What struck me most about the message, however, was the final line—which expanded upon the code of conduct for participation in the annual conference. It stated that ASEEES would “consider the spreading of disinformation” a violation of this code, and it asked all participants in this year’s convention, which will be held in Chicago, to be especially “aware of how language or images may be perceived by others.”[59]

These kinds of appeals—spread out across scholarship and teaching, sent out by both major organizations and individual researchers—were what I had been hoping for. They make it clear that research on Russia does not have to end, but what constitutes our practice, and the nature of our investigations, will have to change.[60] This is a moment where real innovation is possible, where fresh narratives and understandings can finally find a foothold. It is a time in which new hierarchies of value can be established and, in the case of art, this might give rise to shifts in status that allow new works and makers from long-understudied regions to come to the fore. As old notions of what constitutes “greatness” are reevaluated (and interrogated for the role they have played in formulating hegemonic narratives), it will be possible to amplify a wider variety of voices and perspectives, enriching our understanding of the complexity of the region and its cultural production.

In many ways, this moment—fraught as it is with both opportunities and challenges—reminds me of the efforts to decolonize art history that have been unfolding in recent years. Thinking about the parallels and divergences between what is now occurring in Russian studies and the kind of critical reassessments happening in art history led me to return to the special issue of the journal Art History which was devoted to decolonizing the field, coedited by Catherine Grant and Dorothy Price in 2020. There was much in the issue that could be applied to the situation Slavicists now find themselves in. When Tim Barringer wrote that “art history can decolonize itself only to the extent that it acknowledges that Euro-colonial art and our discipline itself are themselves products of empire,” I immediately thought that the same was true of Russia.[61] The field will only be able to divest itself from imperialist narratives once it admits that it has, like the empire itself, been built on subordinating non-Russian voices and perspectives. And as Pamela Corey wrote: “To decolonize art history now is to cite, expose, and critically respond to the structures and residues of the colonial project as they have shaped the discipline and its institutionalization.”[62] This is exactly the challenge that those of us who work at the intersection of art history and Russian studies are now facing.

At the same time, however, I have concerns about how all this will be achieved on a practical level. How are graduate students, for instance, many of whom are at the forefront of these efforts to decolonize, going to write their dissertations when they can no longer work in Russian archives, see the art held in museum storage areas, or access the wealth of sources in Russian libraries? What are those who are working on books and articles about Russian paintings, prints, drawings, and sculpture going to do when they cannot obtain the rights to reproduce works of art in their illustrations? Or, thinking even more specifically, how is someone who is writing on the Ukrainian landscape painter Arkhip Kuindzhi (1842–1910) going to continue their research, given that the museum devoted to his works was destroyed in late March?[63]

Yet again, I think this is an instance where those of us who work across these disciplines have insights to offer that might propel the kind of decolonization efforts outlined in the special issue of Art History to new levels. For this is not just about studying Russian art in a way that does not perpetuate hegemonic center/periphery narratives or reinforce old discourses that have been used to undermine Ukrainian cultural narratives. Anyone who continues to write about or teach Russian art now is engaged in the study of an active colonizer. There is no benefit of historical hindsight here, no distancing from the acts of atrocity, no dignified objectivity that allows for critical detachment. But do we have tools for this kind of work in art history?

So often discussions of decolonization tend to focus on making up for past brutalities or on recalibrating the way we look at the Euro-American past. The legacies of these circumstances—whether we are talking about the history of American slavery, Japanese colonialism in Asia, or the oppression of Indigenous peoples in Canada—are undeniably still with us. These earlier phenomena have repercussions in the present (as scholars in postcolonial and critical race studies have been pointing out for decades). But how do we proceed with a case like Russia, where it is not about decolonization as “an approach to the past” (as Zehra Jumabhoy put it in her comments in the special issue of Art History) or about recovering the “‘forgotten’ cultures that comprise the vast colonized past” (as James Elkins wrote)?[64] Is it possible to think about histories of imperialist conquering at the same time as the horrors of such efforts to subjugate and destroy are being carried out? I am not sure. But we must try.

Those of us who study Russian art are certainly not the first to find ourselves at such a precarious juncture, and we will probably not be the last. Scholars found ways to keep studying German art in the years after Adolf Hitler brought Europe to its knees, and those in Persian studies carried on despite being largely shut out of Iran after the revolution in 1979.[65] Decolonizing the history of Russian art may look different than efforts to decolonize in other cultural contexts. It will require more than simply making it more inclusive or transforming its canon so that it is less hierarchical and Russia-centered. One thing is certain: decolonization in this instance will not mean turning away from the study of art that was produced in the former Russian and Soviet empires. What we need now is not the cancellation of all things Russian but an exhaustive exposé of Russia for what it really is.

At no time have the stakes of such decolonizing efforts been higher. Nor can I think of a case where the need is more urgent. It must happen right now. If this work does not begin immediately, then we will be forced to heed the demands in the op-ed I opened with and boycott Russia and its cultural patrimony entirely. In the end, I hope this article has perhaps served as something of a cautionary tale about what happens when imperialist legacies do not undergo decolonization (or do not undergo them quickly or thoroughly enough). In this sense, Russia presents challenges that are unique within the larger field of art history, but it also affords us an opportunity to think through the broader moral implications of our work as cultural historians, regardless of the geographical areas each of us works on.

I want to close by explaining why I titled this piece “Farewell to Russian Art.” I chose the title because I knew that the publication of this article would mean I could never go to Russia again—at least not as long as Putin or any of his followers or close associates are in power. So much of what I have written here forecloses the possibility that I will ever again be granted a visa to enter the country. And even if I was, I fear it would be too dangerous, given how clear I have made my feelings on the war and Putin’s use of art for political maneuverings. The moment I referred to the war as “unjustified” or wrote that the Russian government is using “lies” to justify the invasion of Ukraine, I knew it was over for me. Having now called Piotrovsky “boot-licking” in print, I also imagine that the Hermitage will not be a place I can visit or obtain image permissions from any longer.

To say that I am devastated by these losses would be a great understatement. Many years ago, I decided to devote my life to studying the art and culture of Russia. I developed relationships with curators and scholars and people there, and it became like a second home in my mind—a place I loved to visit and explore, filled with paintings that are as much puzzles as they are treasures. But now, I must say farewell to all that. I know it is time to part ways with the Russia I thought I knew, but which perhaps never existed. Now is the time for new projects to commence, ones that are more just, more clear-sighted, and more careful. My hope is that this new work will help advance the coming of a glorious post-Putin Russia and an even more glorious free and autonomous Ukraine.

Notes

This article is dedicated to my paternal grandmother, who was born Sophia Lukasky in New York City in 1914 to parents who hailed from Ukraine.

All translations, unless otherwise noted, are my own.

[1] Oleksandr Vynogradov and Lisa Korneichuk, “Russian Cultural Elites Want to Call This Putin’s War. But They, Too, Bear Responsibility for the Atrocities in Ukraine,” Artnet News, March 3, 2022, https://news.artnet.com/.

[2] This volume, coedited with Maria Taroutina and titled Russian Orientalism in a Global Context: Hybridity, Encounter and Representation, 1740–1940, is scheduled to be published by Manchester University Press in 2023.

[3] Jennifer Gould, “Art Collectors Call for Boycott of Russian-Owned Phillips Auction House,” New York Post, March 2, 2022, https://nypost.com/. In the face of these protests, Phillips announced on March 3, 2022, that it would donate the full net proceeds from its twentieth-century and contemporary art evening auction in London to the Ukrainian Red Cross Society. See Taylor Dafoe, “Russian-Owned Phillips Will Donate the Full Net Proceeds from Its London Sale—$7.7 Million—to the Ukrainian Red Cross Society,” Artnet News, March 3, 2022, https://news.artnet.com/.

[4] Norman Lebrecht, “Breaking: Wales Bans Tchaikovsky,” Slipped Disc, March 9, 2022, https://slippedisc.com/.

[5] The full open letter can be read at: https://ui.org.ua/.

[6] I would like to thank my colleagues in the Department of Visual Arts at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette for their immediate support of this new course (now titled “Russian and Ukrainian Art”) and for allowing me to offer it immediately, in the fall of 2022.

[7] As of August 7, 2022, this post remains up on the Tretyakov Gallery’s Instagram feed and can be viewed in its entirety here: https://www.instagram.com/.

[8] “B эти дни мы, как и все, внимательно и с тревогой следим за происходящими событиями, которые никого не могут оставить равнодушными. Мы верим, что культура призвана объединять людей, давать надежду, формировать пространство для диалога, способствуя взаимопониманию. Музей остается открытым, мы корректируем наши планы и продолжаем работать для вас, отстаивая гуманистические ценности.”

[9] “Russia Criminalizes Independent War Reporting, Anti-War Protests,” Human Rights Watch, March 7, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/.

[10] The essay I submitted was a slightly modified version of the talk I gave at the conference, entitled “Masculinity and Partnership: The Artel of Artists, the Peredvizhniki, and Fraternal Values from 1863–1885.” In the last correspondence I had with the Tretyakov Gallery, they indicated that they were having my text translated into Russian and that it would be published under the title “Мужское начало и товарищество: артель художников, передвижники и братские ценности 1863–1885.” The full program of the conference, with a list of all the presenters, can still be viewed, in Russian, on the Tretyakov Gallery’s website (as of August 1, 2022): https://www.tretyakovgallery.ru/.

[11] Martin Bailey, “After Amsterdam, the Hermitage Foundation UK Now Also Cuts Ties with the St Petersburg Museum,” The Art Newspaper, March 9, 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/.

[12] Pola Lem, “Russia Bars Academics from International Conferences,” Times Higher Education, March 22, 2022, https://www.timeshighereducation.com/.

[13] All these statements and withdrawals are described by Sophia Kishkovsky in “Cold War Era Returns as Cultural Ties Are Severed between Russia and US,” The Art Newspaper, July 8, 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/.

[14] All quotes in this paragraph are found in Kishkovsky, “Cold War Era Returns.”

[15] Information about this conference, which was organized by the Comité International d’Histoire de l’Art (CIHA), can be found at: http://www.ciha.org/. My essay, entitled “Russian Occidentalism: The Hybrid Self in 18th-Century Russian Portraiture,” can be found in the conference proceedings: Terms: Proceedings of the 34th World Congress of Art History, ed. Shao Dazhen, Fan Di’an, and Zhu Qingsheng (Beijing: Commercial Press, 2019), 3:1530–34.

[16] This statement, entitled “CAA’s Anti-Colonialism Solidarity Statement,” was published in CAA News Today on March 2, 2022, on the College Art Association’s website, accessed August 29, 2022, https://www.collegeart.org/.

[17] Rachel Spence, “How the Hermitage Museum Artwashes Russian Aggression,” Hyperallergic, March 6, 2022, https://hyperallergic.com/.

[18] See “Hermitage in Facts and Figures” on the official website of the State Hermitage Museum, https://hermitagemuseum.org/.

[19] This decree (no. 984), dated November 29, 2011, is described briefly on the State Hermitage Museum’s website: https://hermitagemuseum.org/. Before it went into effect, a decree dated June 12, 1996, placed the State Hermitage Museum under the personal patronage of the president of the Russian Federation.

[20] The quote and other information in this paragraph comes from Sophia Kishkovsky, “‘Putin’s Been My Person Since the 90s’: Ahead of Russia’s Parliamentary Elections, Hermitage Director Mikhail Piotrovsky Talks Politics,” The Art Newspaper, September 17, 2021, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/.

[21] Sophia Kishkovsky, “Russia and Syria Sign Agreement to Restore Ancient City of Palmyra,” The Art Newspaper, November 27, 2019, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/.

[22] The original Russian reads: “А наши последние выставки за рубежом - это просто мощное культурное наступление. Если хотите, своего рода ‘спецоперация’. Которая многим не нравится. Но мы наступаем. И никому нельзя дать помешать нашему наступлению.” For the complete interview, see Elena Yakovleva, “Почему необходимо быть со своей страной, когда она совершает исторический поворот и выбор. Отвечает Михаил Пиотровский” (Why it is necessary to be with your country when it makes a historical turn and choice. An interview with Mikhail Piotrovsky), Rossiiskaya Gazeta, June 22, 2022, https://rg.ru/.

[23] The original Russian reads: “Хотя радость, с которой они кинулись нас осуждать, рвать и изгонять, опять же говорит о том, что мы сильны в культуре.” Yakovleva, “Почему необходимо быть со своей страной.”

[24] The interview first came on my radar when I saw a short piece on it by Bendor Grosvenor in late June, 2022. He describes the interview (and the way that Piotrovsky inherited his position from his father) as “all a bit North Korean,” and goes on to summarize the situation aptly: “Perhaps when people owe their jobs to politics, rather than competence, it’s not surprising they leap to defend their political masters.” See Bendor Grosvenor, “Dictator Museums,” Art History News, June 28, 2022, https://www.arthistorynews.com/.

[25] “‘Love, Friendship, and Unashamed Social Climbing’: A New Show Reveals the Story Behind Fabergé’s Opulent Egg-Making Atelier,”Artnet News, November 25, 2021, https://news.artnet.com/.

[26] Tessa Solomon, “Hermitage Pulls Raphael Painting from Major Retrospective at London’s National Gallery,” ARTnews, March 11, 2022, https://www.artnews.com/.

[27] For more on these exhibitions, held at the Colección Museo Ruso in Málaga from October 30, 2021 to April 24, 2022, see “Exposiciones Pasadas,” Colección Museo Ruso, accessed August 29, 2022, https://www.coleccionmuseoruso.es/.

[28] Sara Rossi, “Italian Museums to Return Loaned Works to Russian Galleries,” Reuters, March 10, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/.

[29] The show, titled The Morozov Collection: Icons of Modern Art, ran from September 22, 2021 to April 3, 2022.

[30] Fascinatingly, both Putin and French President Emmanuel Macron contributed essays to the catalogue. Putin’s read, in part, “Events as significant as these in the field of culture and art, symbolically connecting Russia and France, consolidate the long-standing special relationship between our countries and undoubtedly contribute to the continuing development of bilateral cultural links.” Bernard Arnault, President of the foundation, said something not altogether dissimilar: “I am confident that [the Morozov exhibition] will constitute a memorable moment celebrating the cultural friendship between France and Russia.” Quoted in Chris Jenkins, “Fondation Louis Vuitton Presents the Morozov Collection,” Arts and Collections, accessed August 29, 2022, https://www.artsandcollections.com/.

[31] Vincent Noce, “Masterpieces from Morozov Collection Return to Russia from France—But Three Works Have Been Retained,” The Art Newspaper, May 25, 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/. I should point out, however, that not all oligarchs found themselves the subject of such interdictions in terms of their art holdings. Israel’s official Holocaust memorial and museum, Yad Vashem, attempted to intervene in sanctions against Roman Abramovich, even though he has been a longtime supporter of Putin. They argued that such sanctions would harm Jewish institutions that rely on his philanthropy. See Shira Rubin, “Israel’s Holocaust museum is so dependent on a Russian Oligarch that it wants to protect him from sanctions,” The Washington Post, March 2, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/.

[32] Farah Nayeri, Takedown: Art and Power in the Digital Age (New York: Astra House, 2022), 182.

[33] Quoted in Patrick Radden Keefe, “The Family That Built an Empire of Pain,” New Yorker, October 23, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/.

[34] They also set up a new Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/dutch.heritage.amsterdam. See Sophia Kishkovsky, “Hermitage Branch in Amsterdam Rebrands After Cutting Ties with Russia,” The Art Newspaper, April 1, 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/. It should be noted that not everyone was so quick to divest. The general secretary of the Hermitage Italy, Maurizio Cecconi, continued to actively champion the alliance well into March.

[35] Tessa Solomon, “Faced with Local Opposition, Russia’s Hermitage Museum Could Call Off Barcelona Satellite,” ARTnews, January 28, 2022, https://www.artnews.com/.

[36] The case that was most often in the news involved the Russian billionaire Vladimir Potanin, who stepped down from his role as a trustee at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in early March. See Valentina Di Liscia, “Russian Oligarch Steps Down as Guggenheim Trustee as Outrage Grows Over Ukraine Invasion,” Hyperallergic, March 3, 2022, https://hyperallergic.com/.

[37] Those in positions of authority should probably also start weaning themselves off loans of artworks from the collection of the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, given the role he played in the murder of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018. Museums might also consider whether it is appropriate to negotiate loans of artworks with a country that routinely punishes homosexuality with death and conducted a mass execution of eighty-one men in March of 2022. For more on human rights abuses in Saudi Arabia, see “Saudi Arabia: Mass Execution of 81 Men,” Human Rights Watch, March 15, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/.

[38] Russell Hotten, “Ukraine Conflict: What Is Swift and Why Is Banning Russia So Significant?” BBC News, May 4, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/.

[39] This situation will also hit hardest those who work on less canonical artists or long undervalued media like printmaking. While many of the most popular artworks in the Hermitage’s collection are available in the public domain, there are many thousands of objects that can only be viewed on the Hermitage’s website (and those images cannot be reproduced without the museum director’s permission).

[40] Ben Quinn, “National Gallery Renames Degas’ Russian Dancers as Ukrainian Dancers,” The Guardian, April 3, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/.

[41] Quinn, “National Gallery Renames Degas’ Russian Dancers.”

[42] Thomas M. Prymak, “A Painter from Ukraine: Ilya Repin,” Canadian Slavonic Papers / Revue Canadienne des Slavistes 55, no. 1/2 (March/June 2013): 20–21, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23617571 [login required].

[43] See Svitlana Shiells, “Ilya Repin’s Ukrainian Heritage,” Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard University News, September 27, 2016, https://huri.harvard.edu/.

[44] The sentence reads in full: “Связь с родным городом и Слободской Украиной Илья Репин пытался сохранять до конца жизни, а украинские мотивы занимали важное место в творчестве художника.” There is, in addition, a hint at Repin’s Ukrainian roots in a brief section on “The House Museums of Repin [Музеи-усадьбы Репина],” where it is noted that there are currently four museum-estates devoted to Repin—in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. But no further explanation or description of the Repin museum in Ukraine is given. See “Репин, Илья Ефимович” (Repin, Illia Efimovich), Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, last modified August 2, 2022, 18:15, https://ru.wikipedia.org/.

[45] “Ilya Repin,” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, last modified August 14, 2022, 19:52, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

[46] Charlotte Douglas, Kazimir Malevich (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994), 7, 44.

[47] Piotr Piotrowski, Art and Democracy in Post-Communist Europe, trans. Anna Brzyski (London: Reaktion Books, 2012), 23; and Charlotte Douglas, preface to Rethinking Malevich: Proceedings of a Conference in Celebration of the 125th Anniversary of Kazimir Malevich’s Birth, ed. Charlotte Douglas and Christina Lodder (London: Pindar Press, 2007), i. It is worth noting that Russian scholars are also often very careful to accurately portray Malevich’s heritage. For an example of this kind of transparency, in this case from one of the world’s leading Malevich specialists, see the Q&A which followed Aleksandra Shatskikh’s talk on Malevich entitled “Black Square: Malevich and the Origin of Suprematism” at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in 2014. Available from YouTube, beginning at 46.50, https://www.youtube.com/.

[48] These descriptions can be found on the museums’ websites. See the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, https://buffaloakg.org/; the Yale University Art Gallery, https://artgallery.yale.edu/; and the Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/.

[49] It is worth pointing out that these distinctions are also considered important in Russia. Censuses conducted by the Soviets always distinguished between narodnost’ (ethnicity) and natsional’nost’ (nationality). The former was determined by language spoken, while the latter by ethnic group declared, even if the ethnic language was not spoken. For more on these terms and their use in earlier periods, including in the nineteenth century, see Alexey Miller, “Natsiia, Narod, Narodnost’ in Russia in the 19th Century: Some Introductory Remarks to the History of Concepts,” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 56, no. 3 (2008): 379–90, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41052105 [login required].

[50] Allison Leigh, “Between Communism and Abstraction: Kazimir Malevich’s White on White in America,” American Communist History 18, no. 2 (Summer 2019): 1–15, https://www.tandfonline.com/ [login required]. The references to Malevich as a “Russian artist” or “Russian painter” can be found on 3, 8, and 13.

[51] Allison Leigh, “Il’ia Repin in Paris: Mediating French Modernism,” Slavic Review 78, no. 2 (Summer 2019): 434, https://www.cambridge.org/ [login required].

[52] The line from the letter I cite reads: “I think that this is a disease among us, Russian artists, jammed with literature. We do not have that burning, childlike love of form. . . . Our salvation is in form, in the living beauty of nature, but we crawl to philosophy, to morality.” Letter from I. E. Repin to E. P. Antokolskii, August 7, 1894, in Illia Repin, Izbrannie Pis’ma (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1969), 2:74. Cited and quoted in English in Molly Brunson, Russian Realisms: Literature and Painting, 1840–1890 (Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2016), 128.