In the Picture: The Emergence of the Female Amateur in Fin-de-Siècle Exhibition Posters in Brussels

by Ulrike Müller and Marjan SterckxUlrike Müller is a lecturer in heritage studies at the University of Antwerp and a research associate at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, specializing in the history and theory of collections and museums. She received a joint PhD in art history and history from the Universities of Ghent and Antwerp, respectively (2019), with a dissertation on the public role of private art-and-antique collectors in Brussels, Antwerp, and Ghent during the long nineteenth century. Her research focuses on the history of taste, material culture, public and private collecting, and the art market, in Belgium and internationally. She has published on the accessibility, display, and function of private collections in nineteenth-century Belgian cities; private collectors’ interaction with public cultural life in the past and the present; and the historical origin and sociocultural context of several Belgian museums and collections.

Email the author: Ulrike.Muller[at]uantwerpen.be

Marjan Sterckx is associate professor of art history at Ghent University, where she lectures on the history of nineteenth-century art and the history of interior design. She is the founding chair of the research group The Inside Story: Art, Interior and Architecture, 1750–1950 (ThIS), and supervises several PhDs in this field. Sterckx is a board member of the European Society of Nineteenth-Century Art and is founding coeditor of Brepols’ book series XIX: Studies in Nineteenth-Century Art and Visual Culture and the journal Tijdschrift voor Interieurgeschiedenis en Design. Her research considers the intersections between art, gender, and space during the period ca. 1750–1950. She coedited, with Tom Verschaffel, Sculpting Abroad: Nationality and Mobility of Sculptors in the Nineteenth Century (Brepols, 2020), and coedited, with Thijs Dekeukeleire and Henk de Smaele, Male Bonds in Nineteenth-Century Art (Leuven University Press, 2021). In 2021, she curated the exhibition Crime Scenes in Ghent.

Email the author: Marjan.Sterckx[at]ugent.be

Citation: Ulrike Müller and Marjan Sterckx, “In the Picture: The Emergence of the Female Amateur in Fin-de-Siècle Exhibition Posters in Brussels,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 21, no. 3 (Autumn 2022), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2022.21.3.3.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

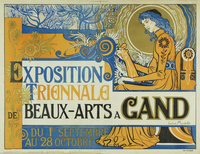

During the final decades of the nineteenth century, a new type of image emerged in Western visual culture, representing women and their intense engagement with art. In diverse media—including paintings, prints, and most notably in the emerging artistic poster as of the 1890s—women are captured in an intimate dialogue with precious objects, such as small-scale sculptures, engravings, pictures, or bibelots (fig. 1). In these images, women usually appear alone or, at times, in the company of another woman, in a gallery, artist’s studio, or another exhibition space, where they are shown immersed in the contemplation of their objects of interest. Almost invariably, they are shown wearing colorful, flowing, and elegant garments and elaborate accessories reflecting the influence of the contemporary art nouveau style. Dressed according to the latest fashion, these women can be identified as models of la femme nouvelle (the modern woman). Writing about the paintings of US artist William Merritt Chase (1849–1916), Isabel Taube characterizes such representations of female amateurs as novelties that radically modernized the existing image of the art lover, who still was predominantly male. They did “not conform to stereotypical portrayals of women in genre scenes with interior settings” and, most importantly, they indicated “the ‘feminization’ of art consumption during this period.”[1] In a similar vein, Ruth Iskin describes the rise of the iconography of the female print connoisseur in the new medium of the poster as a major artistic innovation during the 1890s, and identifies Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901) as “the first to represent a contemporary woman as a connoisseur of prints in a color lithograph.”[2] In observing how this imagery “broke with the tradition of representing print connoisseurship as a masculine practice,” Iskin argues that “representations of the female print connoisseur signified the democratization of collecting,”[3] a development that paralleled the rise of prints and posters as new collectors’ items and women as contributors to the expansion of this new culture of collecting.[4]

Iskin has also shown how the new iconography of the female amateur was “part of a broader phenomenon representing modern women in numerous roles.”[5] Highlighting the 1890s as the heyday of the femme nouvelle and of poster culture, she shows how the new medium was frequently used to represent women—via advertisements for such varied products as art prints, cigarettes, and bicycles—as highly visible and active agents in the expanding social and cultural life of the fin de siècle.[6] Posters not only reflected but also stimulated and popularized women’s new position in the public sphere through imagery that “helped shape the changing images and identities of modern women.”[7]

Building on the existing research of Taube and Iskin, this article addresses the question of what precisely the new imagery of the female amateur can tell us about changing perceptions of women’s position in the art world in Belgium during the fin de siècle, and how these images relate to women’s actual presence and role in exhibitions, artistic salons, and similar cultural events. We will examine the iconography of the female amateur in art nouveau posters designed to advertise art exhibitions in Brussels during the 1890s, with a particular focus on representations of women looking at and/or manipulating artworks and other precious objects. In this period, remarkable numbers of such posters were created in the Belgian capital, especially intended to promote exhibitions of modern art, including graphic and decorative arts. We will analyze in particular how these avant-garde exhibition posters represented fashionably dressed female art lovers as self-confident, assertive, and at times even provocative femmes nouvelles, thereby positioning them literally at the center of a new visual culture that reflected and at the same time encouraged their increased participation in the cultural sphere of fin-de-siècle Brussels. Taking into consideration the visual characteristics of these posters as well as contemporary documentary sources, we will argue that matters of fashion, distinction, and exclusivity were important factors that determined women’s presence and participation in the expanding art world in Belgium, and in particular its capital, at the turn of the twentieth century.

Home to a prosperous economy as well as a wealthy, liberal elite culturally and intellectually oriented toward Paris, Brussels was renowned for its flourishing avant-garde art scene and exhibition culture during the fin de siècle.[8] The city’s modern art scene thrived on a close-knit social network of socially and culturally progressive art animateurs (stimulating people), among whom the lawyers Edmond Picard (1836–1924) and Octave Maus (1856–1919) played a crucial role.[9] These two men stood at the foundation of the avant-garde art associations Les XX (The Twenty) (1884–93) and La Libre Esthétique (The Free Aesthetics) (1894–1914), and they were the founding editors, as of 1883, of the progressive art journal L’Art moderne, which functioned as the main public organ for voicing the artistic ideals of the avant-garde movement in fin-de-siècle Brussels.[10] This network, moreover, facilitated the organization of novel art exhibitions and a wide range of related events, including concerts, lectures, and semipublic salons, in which women increasingly participated as exhibiting artists, performers, lenders, and members of the audience.[11] The female amateur as an aesthetic motif adopted a hitherto unseen centrality in posters advertising the Salons of La Libre Esthétique. To be sure, not all posters for these exhibitions featured representations of women in the role of the engaged art lover; more conventional art nouveau imagery was also frequently used to draw attention to these shows, including stylized landscapes and women picking fruit or flowers.[12] However, posters such as the one advertising the 1900 Salon of La Libre Esthétique, which was designed by Léontine Joris (1870–1962), a female affichiste (poster artist) working under the pseudonym Léo Jo (fig. 2), show female visitors to the exhibition as prominent and decidedly modern figures actively involved with the arts in the public sphere. In discussing this example, Laurence Brogniez and Vanessa Gemis observed that such posters “give a veritable feminine identity to these Salons.”[13]

In this article we analyze the most representative and illustrative posters created during the 1890s for the purpose of advertising a range of different art exhibitions and made by the principal Belgian artists active in the field, including Henri Privat-Livemont (1861–1936), Théo van Rysselberghe (1862–1926), Armand Rassenfosse (1862–1934), and Auguste Donnay (1862–1921).[14] We will examine these posters and their visual language, as well as the actual presence and reception of women at the exhibitions they advertised, in the context of the avant-garde art and culture that flourished in fin-de-siècle Brussels. By combining close visual analysis with historical contextualization and the examination of contemporary archival and published sources, including exhibition catalogues and reviews in newspapers and art journals, we will show how these posters positioned contemporary art exhibitions as sites of alternative aesthetic experience and sociocultural distinction.

Picturing the Femme Nouvelle in Paintings and Posters

During the 1890s, the art nouveau poster witnessed a rapid blossoming in Belgium, in close connection to, and under the influence of, contemporary Parisian print culture. French posters were frequently exhibited at the Salons of Les XX and La Libre Esthétique, indicating the Belgian avant-garde’s strong admiration for modern French designs. In 1893, for example, a number of Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters were shown at the Salon of Les XX, including Le Divan Japonais (The Japanese Divan) and Aristide Bruant et son cabaret (Aristide Bruant and His Cabaret). Commenting on this show, L’Art moderne particularly appreciated Toulouse-Lautrec’s radically modern style, especially his “juxtaposition of flat tones” and his “synthesis of essential lines,” which were described as “truly prodigious.”[15] In the same year, the country’s first exhibition exclusively dedicated to contemporary French posters was held in the museum of Ixelles, a suburb of the Belgian capital known as a hot spot of the avant-garde.[16] The exhibition, which showcased works by, among others, Jules Chéret (1836–1932), Toulouse-Lautrec, and Eugène Grasset (1841–1917), was warmly received in the contemporary art press. The enthusiastic review in L’Art moderne hailed the medium of the poster as the ideal means by which to reach new audiences and explicitly expressed the hope that the exhibited posters might stimulate a prolific production of this new artistic medium in Belgium so that “one day, the streets of Brussels may become museums of beautiful works displayed in the open air.”[17] The reviewer, however, also emphasized that this would require that “the organizers of festivals and fairs . . . assign the execution of the posters to others than old geezers or twentieth-rate painters.”[18]

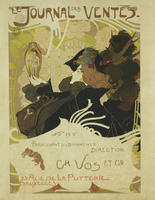

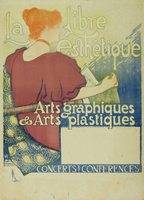

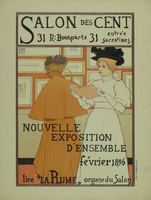

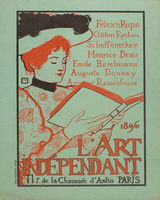

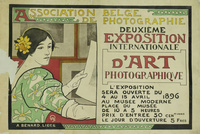

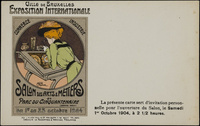

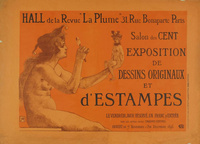

During the following years, the production of illustrated posters in Belgium did significantly increase, and—perhaps not surprisingly—avant-garde artists and exhibition organizers responded to L’Art moderne’s call to promote this development, the latter by commissioning posters for their public cultural events. In 1896—only three years after the Ixelles show—another poster exhibition was held in Brussels, now showcasing Belgian affiches (posters) alongside important French examples.[19] Notably, the exhibition took place at the Maison d’Art (House of Art), the semipublic gallery space housed in the former home of Picard that, between 1894 and 1900, hosted a broad range of exhibitions, concerts, and other cultural events in an alternative setting characterized by its quasi-domestic and aesthetic atmosphere.[20] In an article published on the occasion of the opening of the exhibition, L’Art moderne praised the enormous progress that had been made in the previous years in the production of artistic posters in Belgium, mentioning as particular achievements Van Rysselberghe’s poster for the 1896 Salon of La Libre Esthétique (fig. 3), Rassenfosse’s posters for the Salon des Cent (Salon of the One Hundred) (fig. 4) and the exhibition of the artists’ association L’Art Indépendant (Independent Art) (fig. 5), both held in Paris in the same year, and Auguste Donnay’s poster for L’Exposition d’Art Photographique (The Exhibition of Photographic Art) (fig. 6)—all of which date to 1896 and were displayed at the exhibition.[21]

The aforementioned posters all feature representations of female art amateurs, captured in acts of close inspection of a work of graphic art: an illustrated book, a framed print on the wall, or an unframed photograph. The women are characterized by their calm and graceful postures as well as their attentive, discerning gazes, giving them an air of natural self-confidence and agency. One of their most striking features is their fashionable attire: voluminous dresses with puff sleeves, and long gloves or overcoats, in bright, plain colors or decorated with extravagant flower motifs. Some wear lavish hats or a flower in their hair, or have swirling hair. Four of the five women have red hair, a seemingly omnipresent feature of female amateurs in Belgian posters that indicates the strong influence of the English Pre-Raphaelites on art circles in Brussels at the fin de siècle. This feature may also suggest the women’s ambiguous identity as femmes fatales, attractive and dangerous at the same time, foregrounding their modern style and relative freedom. Their appearance identifies them as exponents of the femme nouvelle, a privileged woman who profited from educational, legal, and professional changes occurring during the 1890s and who appeared more prominently in the public sphere.[22] In addition to their modern and unconventional appearance, the women’s self-confident fashionableness also draws attention to the ease and determination with which they move in their expanding environment. Iskin notes that the women represented in turn-of-the-century posters emphasize “the private experience of the sole female . . . connoisseur in the intimate space of the gallery,” while at the same time their highly fashionable outfits tie them to “the public spaces of spectacle.” According to Iskin, it was precisely this paradoxical combination of intimacy and fashionableness that assured them distinction.[23] Finally, by way of their self-confident modernity and their interest in art, the women represented in these posters draw particular attention to the newness of the exhibitions that the posters advertise.

Yet the iconography of the female amateur that flourished in art nouveau posters in the 1890s and early 1900s was not entirely new, nor exclusive to posters. In that same period, images of women represented in close interaction with art also became increasingly popular in Belgian painting. Gustave Vanaise (1854–1902), for example, painted a woman intimately engaged with art in an interior, which according to the title can be identified as an artist’s studio—maybe Vanaise’s own (fig. 7). Sitting in an armchair in a flowing yellow dress with large puff sleeves and turned away from the viewer, the woman has paused in her reading, keeping her finger on the right page of the book resting on her knees, just as Victorine Meurent (1844–1927) does in Édouard Manet’s painting The Railway (1873; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC), indicative of the temporary nature of the interruption. She is shown immersed in the contemplation of a large, framed artwork that stands on the floor next to her. The painting within the painting represents a historical scene, apparently by a Flemish old master—Vanaise admired Peter Paul Rubens’s (1577–1640) work. In the interior, a diversity of other artworks and artists’ attributes are visible, including a large sculpture or plaster cast of a horse. The same horse appears in another of Vanaise’s compositions, significantly entitled L’Amateur d’art (The Art Amateur) (fig. 8), suggesting that the sculpture was part of the artist’s studio interior. In the second painting, a slender woman is standing in front of a sideboard or console table placed against a wall densely covered with paintings in the style of the old masters. The scene features Frans Hals’s (ca. 1581–1666) The Gypsy Girl (1628; Musée du Louvre, Paris) in the upper right—or perhaps a copy of it, judging from its slightly cropped format.[24] In contrast to the sensuous facial expression of Hals’s Gypsy Girl and the explicit display of her décolleté, the female visitor to the studio is represented as a decent bourgeois woman, wearing a black skirt and tight red blouse with a high collar and modest puff sleeves that accentuate her small waist and elegant posture. Even though she is standing in close vicinity to Hals’s painting, she is not looking at it. Instead, she is focusing on a print she is holding, which seemingly represents a female figure in a landscape, perhaps in the style of Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721) or Thomas Gainsborough (1727–88). In both Vanaise’s paintings, the women are shown without a cloak, emphasizing the more private atmosphere of the scenes and suggesting that they have come to the artist’s studio not simply for a brief visit. The paintings represent the women as seriously involved with the art they are viewing. Shown with their backs to the viewer and therefore unaware of the beholder, the fashionably dressed women seem to be completely immersed in and absorbed by the artwork they are studying, rather than appearing as more theatrical, self-aware presences in the here and now of the contemporary art world.[25]

Other, slightly older, paintings represent women in the company of their husbands, a chaperone, or alone in museums and other public exhibition spaces, indicating that they featured prominently among the growing audience for these new venues. Museums were ever more eager in this period to make their collections accessible not only to art students but also to visitors from the broader middle class who desired to experience art in the public sphere and to learn more about its nation’s artistic heritage.[26] For instance, in 1886, Louis Pion (1851–1934) painted a young woman and her older companion visiting the Brussels Museum of Fine Arts (fig. 9). The young woman is shown looking up admiringly at a sculpture on a pedestal of a nude, seated youth holding a statuette—Thomas Vinçotte’s (1850–1925) Giotto of 1874.[27] Her chaperone looks away and seems embarrassed amid the many nude sculptures in the room. In the same year, Henri van Dyck (1849–1934) painted a sole female visitor in the monumental halls of the Antwerp Academy Museum holding up a small, open booklet—the museum’s catalogue (fig. 10).[28] While these images seem to focus on the impressive art spaces themselves and emphasize the educational function and the edifying character of the museum visit, they also illustrate the increased presence and visibility of women in Belgian museums and the role such visits played in women’s formation. In contrast to these images that reflect the bourgeois values of education and respectability, the posters, in turn, radically foreground modern, self-confident women, usually showcasing them in much more tightly framed compositions. The posters present a view of these women that places a stronger emphasis on vicinity and intimacy, thereby bringing them to the center of the image while simultaneously acknowledging them as an intended audience for art.

New Visual and Tactile Experiences

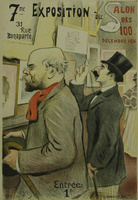

Rassenfosse’s poster for the 1896 Paris Salon des Cent features two women in a gallery space, one of whom is shown from the back while attentively examining the prints on the wall with the help of hand-held eyeglasses (see fig. 4). This motif might have been influenced by French illustrator Fernand Fau’s (1858–1919) poster of 1895 for the same exhibition—the Salon des Cent was a constantly changing commercial exhibition showcasing contemporary graphic arts, including colorful lithographic posters, established in 1894 by Léon Deschamps (1864–99), founder of the Parisian avant-garde literary and artistic magazine La Plume, in whose offices the Salons took place. Fau’s poster similarly showcases a female visitor to the show, dressed in a fashionable dress, coat, and hat, who uses a similar device to examine the exhibited artworks in greater detail (fig. 11).[29] Also known as a lorgnette or face-à-main, this fine pair of eyeglasses with a stem at one side became very popular during the Belle Époque among well-to-do women. As an aid to the visual examination of artworks in the context of an exhibition, the lorgnette clearly distinguishes the female amateur from her male counterpart. The attribute par excellence of the male connoisseur-collector was the loupe or magnifying glass (in private spaces) or the monocle or pince-nez (in public spaces). Both of the latter categories appear, for example, in an 1894 poster for the seventh Salon des Cent (fig. 12) (also showing a cropped figure of a female visitor in the background), emphasizing the duration and seriousness of the act of looking, which was considered characteristic of the connoisseur’s gaze. In a similar way, the lorgnette highlights the intensity and intimacy of the visual experience, while at the same time the more extravagant shape of the device and its conspicuous handling add a more fashionable, elegant, and modern touch to the represented women.

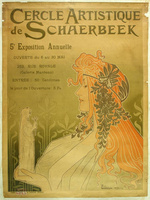

The motif of the female amateur using these eyeglasses frequently appears in Belgian posters during the fin de siècle. Privat-Livemont represented the fashionable trinket several times, such as in his poster for the 1896 Salon of the Cercle Artistique de Schaerbeek (Salon of the Artistic Circle of Schaerbeek) in Brussels, which shows a slim woman in fashionable outerwear looking at a painting on an easel of an equally graceful woman—possibly Fama, the Roman goddess of fame and renown (fig. 13). The bottle of varnish and the cloth on the easel seem to suggest that this female viewer is a privileged visitor, admitted to the show in question—or to the artist’s studio to see an artwork destined for the show—during the vernissage, a private viewing before the formal opening of an exhibition.[30] A poster announcing the Exposition d’Affiches (Exhibition of Posters) held in conjunction with the Brussels World’s Fair of 1897 shows a self-confident, modern woman, holding a lorgnette in her left hand and a fan in her right, immersed in the examination of a modern color print which she inspects while standing slightly below it (fig. 14). The rendering of the woman in profile and the poster’s sharp but harmonious color contrasts accentuate not only her extravagant hairstyle, fashionable dress, and accessories, but also draw attention to her attentive gaze and slight smile, signaling concentration as well as the pleasure of looking. Henri Meunier (1873–1922) depicted the same magnifying device to present his women art lovers as highly engaged beholders, such as on his poster for the Salon des Arts et Métiers (Salon of Arts and Crafts) at the Brussels Cinquantenaire site in 1904, the design of which was reused on the invitation card for the opening (fig. 15).[31] It shows a red-haired, corseted woman with a feathered hat who bends over an art nouveau display case to examine the modern vases and plates it contains with the help of her lorgnette.

Another distinctive feature of the posters discussed in this article is the women’s direct physical engagement with diverse types of objects. The posters often represent female amateurs holding in their hands the artistic objects they are inspecting (see figs. 1, 3, 6). Iskin notes that the frequent representation of women holding and inspecting works of graphic art—including prints, posters, and photographs—mirrors the flourishing collecting culture of such artworks, especially among an emerging group of female amateurs. Modern prints, posters, and other works on paper were usually more affordable for female amateurs than paintings or sculptures and thus were easier for them to collect. In addition, as relatively new collectors’ items, such artworks were much less a part of the traditional—and generally male-dominated—art historical canon, which was strongly comprised of old master paintings that were considered ideal signs of taste and models of an intellectual engagement with art. According to Iskin, the new iconography of the female print connoisseur thus indicates the gendered nature of art consumption at the turn of the twentieth century.[32]

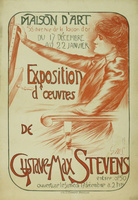

However, Belgian fin-de-siècle posters also represent women handling other types of art. Gustave-Max Stevens (1871–1946), for example, designed a poster for the 1896 exhibition of the art circle Le Sillon (The Furrow)—established in 1893 by pupils of the Brussels Academy and presided over by Stevens himself—showing a female figure in an eye-catching, red reform dress, seemingly engaged in hanging a picture on a wall (fig. 16).[33] Two years later, he exhibited a selection of his works at the Maison d’Art.[34] The poster he designed for this show features a seated woman manipulating a canvas that rests on an easel in front of her and which she examines attentively (fig. 17). Stevens’s fine, monochrome drawing accentuates the woman’s serious gaze, tense body, and outstretched right arm with which she handles the artwork (the other arm rests casually on a traditional armchair), thereby drawing attention to her concentration, self-confidence, discernment, and critical attitude. Another frequent motif in posters representing female amateurs is a woman holding a statuette or another piece of (sculptural) decorative art.[35] The posters by Constant Montald (1862–1944) and Privat-Livemont, for example, each feature a slender, young, and decorative woman—in the case of Privat-Livemont, represented with swirling red hair—who holds in her hands and attentively examines a statuette of a female figure in a long robe (figs. 18, 19).

The representation of female figures in these posters with an emphasis on direct, tactile engagement with diverse art objects recalls similar art nouveau posters designed to advertise other kinds of consumer goods during the 1890s, including coffee (fig. 20), cigarettes, or even salad oil and bicycles.[36] However, posters intended to advertise foodstuffs and other products for daily use can be more readily associated with the kind of direct handling and manipulation by their consumers that is pictured in the prints. But the representation of individuals physically interacting with artworks and other precious objects may not seem appropriate in posters advertising exhibitions. After all, art displays—in museums, galleries, or other exhibitions—usually require maintaining a strict distance between the visitors and the shown objects. The representation of the physical handling of art objects instead recalls images of artists in their studios, private art collectors, and art dealers who, by definition, have unlimited and unrestricted access to their possessions, emphasizing the important role of tactility and the sense of touch in the artist’s and the connoisseur’s practice.[37]

Moreover, unlike art nouveau posters advertising consumer goods, the Belgian affiches representing modern female art amateurs do not advertise a specific product but rather an event—including its corresponding experience. The events these posters advertise are in most cases exhibitions of modern art (graphic and decorative arts included), and often these were organized in the context of the flourishing avant-garde art scene in fin-de-siècle Brussels. For example, the Salons of the art associations Les XX and La Libre Esthétique and the exhibitions organized at the Maison d’Art were characterized by a new approach to presenting art objects. In contrast to the triennial art Salons—alternately organized in Brussels, Antwerp and Ghent—that mainly showcased paintings hung in overwhelming displays of several rows and close to each other, the modernist art circles of the fin de siècle promoted smaller displays with a greater variety of objects, giving more prominence to works of graphic and decorative art, next to paintings and sculptures. At the above-mentioned poster exhibition held at the Maison d’Art in 1896, for example, French and Belgian affiches were deliberately shown together with examples of modern Belgian porcelain that “completed the display” with an “astounding result.”[38] This focus on diversity points to an effort to broaden the artistic canon and elevate “lesser” media such as the decorative and graphic arts. This was a trend typical of art nouveau in general in Brussels in the 1890s and early 1900s, paralleled by a growing demand among the middle class for art objects to decorate their dwellings. Belgium’s avant-garde art circles also developed exhibition concepts that presented more diverse and less numerous art objects in a more integrated and aesthetically appealing manner.

In Picard’s Maison d’Art, for example, works of contemporary fine and applied arts were not only presented alongside one another but also in a domestic setting, complete with furniture, architectural elements, and interior decorations. At its foundation in 1894, the Maison d’Art was presented as an alternative exhibition venue “intended to facilitate the freedom and progress of the Arts in all their contemporary manifestations.”[39] It was also advertised as an establishment where artworks were presented in an “atmospheric and domestic context” with an eye on the “destination for which they have been created.”[40] Visitors were even allowed to touch the exhibited artworks, contributing to the intimate experience of the aesthetic qualities of the objects.[41] This novel approach to displaying and experiencing art objects could, according to Picard, enable a special connection among artists as well as art lovers, one that contributed to participation and the “formation of a compact aesthetic company.”[42] Such discourses of interconnectedness and progress were consciously used to distinguish the venues of the avant-garde from the more conventional artistic circuits as well as “the banal décor of an exhibition hall.”[43]

The posters designed to advertise the exhibitions—and their corresponding experience—at these alternative venues, such as the Maison d’Art, La Libre Esthétique, and Pour l’Art (For Art), among others, reflect these new artistic strategies. By highlighting a greater diversity of art objects and aspects of close inspection and tactility, the posters also give shape to an aesthetic concept characterized by an atmosphere of intimacy and personal experience as well as a strong sense of cross-disciplinary inspiration and interaction, all aspects that were key to the ideals of the artistic avant-garde developed during the 1890s.

Provocation and Emancipation

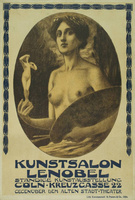

In some of the posters discussed in this article, the visual language of the female amateur’s close engagement with an art object and the associated notions of intimacy and tactility have an erotic undertone. A curious example is a poster by Rassenfosse, initially designed for an exhibition of prints and drawings by Félicien Rops (1833–98) to be held in Brussels in 1896 but recuperated later that year for the Salon des Cent in Paris (fig. 21). The poster shows a naked woman wearing a jester’s hat and holding in her left hand a statuette of a small, nearly nude figure, which she examines with a magnifying glass. The figure strongly resembles the type of prostitute often drawn by Rops. Here, the representation of the woman handling an artwork clearly deviates from that pictured in other posters designed for similar advertising purposes. Exhibition posters usually show the female amateurs as fashionable, self-confidently modern, and at times daring but always fully dressed and decent bourgeois women. In contrast, nude or seminude figures in posters who are shown manipulating artworks and/or artists’ attributes are usually intended as personifications of the arts, as muses, or as similar allegories. The advertisement for the Art Salon Lenobel in Cologne by German artist Hans Deiters (1868–1922), for example, represents a woman holding a sculpture in her right hand and a palette and brushes, the attributes of a painter, in her left (fig. 22). Her nudity and her lofty gaze, as well as the laurel wreath on her head, clearly identify her as an allegorical figure. While her exposed breasts and the naturalistic style in which she is represented would certainly have drawn viewers’ attention in the public sphere, the poster’s idealistic subject matter is essentially in line with bourgeois norms and values.

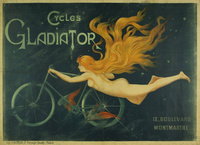

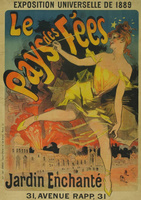

A similar ambiguity is at the heart of numerous posters advertising modern consumer goods and entertainments. Georges Massias’s poster design for the bicycle brand Gladiator, for example, features a nude woman with flowing red hair hovering next to the bicycle she is advertising (fig. 23). She appears in the guise of an allegory of progress and victory, but her sensuous and sexualized body was, in the first place, certainly intended to attract the attention of male buyers.[44] The “sex sells” strategy was most prominently applied in the advertisements designed by Chéret for numerous Parisian entertainment establishments. His posters had an international impact and were also well-received in Brussels, where they featured prominently at the 1893 poster exhibition.[45] In his posters for theaters, bars, and other night-life venues, Chéret frequently used attractive, sparsely clad and often red-haired women to attract the attention of (male) consumers (fig. 24). In so doing, he foregrounded the women not so much as self-confident femmes nouvelles but rather as provocative filles publiques, bohemian women active at the margins of society and thereby breaking with bourgeois standards and conventions.

The naked woman in Rassenfosse’s exhibition poster can hardly be regarded as ideal. Wearing a jester’s hat instead of a laurel wreath and exposing her naked, rather inelegantly posed body, she seems to ridicule all bourgeois conventions of taste. In subject matter and style, the poster clearly refers to the satiric oeuvre of Rops, who was notorious for his provocative and often erotic or even pornographic drawings, prints, and paintings. By transposing this imagery to the medium of the poster, Rassenfosse not only enlarged the imagery’s format but also brought Rops’s iconography out into the open. While Rops’s small-scale graphic works were usually intended for intimate examination in the private sphere, the poster made the provocative imagery publicly visible in the streets, attracting broader attention to the exhibition and to Rops’s controversial art. By this means, the poster underscores the artist’s unconventional style. Sex in advertising is intended to sell, but what it sells here is especially daring newness, modernity and the transgression of the rules of bourgeois society.

In contrast, the two women in Van Rysselberghe’s poster for the 1897 Salon of La Libre Esthétique are fashionably dressed (fig. 25). The red cloaks they are wearing and their tied-up, red hair—as well as the simplified, elegant style in which these elements are represented—demonstrate the influence of Toulouse-Lautrec’s works on Belgian artists.[46] Yet, both women seem caught in an intimate and erotically allusive act while visiting an artist’s studio. One of them holds a nude statuette, which she seems to handle in a sexually suggestive way, while her companion is staring somewhat dreamily at the figurine.[47] Here, the tactile engagement with the artwork—a practice essential to traditional notions and images of the (male) connoisseur—may seem to allude to a casual manipulation of an object for banal pleasure and (sexual) fantasies.

Certainly, such eroticizing subjects were not exclusive to posters; in fact, they were much more common—and usually more explicit—in other, less public, printed or artistic media. In an earlier drawing by Rops entitled Curiosités et comparaisons (Curiosities and Comparisons) (1878–81; Musée Félicien Rops, Namur), two women in evening dresses with low-cut necklines conspiratorially look at a statuette of a nude male figure, which one of them holds in her hands. In light of Rops’s oeuvre, the drawing’s title is undoubtedly meant to be sexually suggestive: What is the subject of the women’s “curiosities,” and with what male bodies are they comparing the idealized statuette? The scrutinizing female gaze of the two women therefore clearly objectifies the male body.[48] Van Rysselberghe’s poster, however, may appear especially provocative and ambiguous given its public function. Remarkably, although destined for placement on the streets (another poster was designed for the same exhibition to be shown in indoor, semipublic spaces), the poster did not arouse any public debate: references to it in the press mainly complimented the lithograph’s bright and harmonious colors, and it quickly became a desirable collector’s item that could be purchased at the print-and-photograph dealer Dietrich & Compagnie in Brussels.[49]

The particular quality of Van Rysselberghe’s advertisement for La Libre Esthétique becomes apparent if one compares its visual language to that of other posters presenting female figures in a sexually suggestive way. Alphonse Mucha’s (1860–1939) 1896 poster for the twentieth exhibition of the Salon des Cent, for example, shows a seductive, nude muse with closed eyes, an exposed breast, and long, decoratively stylized hair, holding a brush and a quill, rather than a femme nouvelle (fig. 26).[50] This passive sensuality stands in strong contrast to Van Rysselberghe’s active rendering of the two female amateurs, seen from the back and the side, fully clothed and with their hair tied up, as elegant and fashionable yet self-assured and resolute modern women. They even demonstrate a certain desire to attract public attention—a desire to be seen: their vivid red and orange dresses, in combination with their wide, flowing overcoats, give them a monumental presence and an air of physical strength and mental self-possession that is absent in Mucha’s seductive fantasy figure. Notably, in this same era, women were increasingly gaining access to art academies and universities in Belgium, and a law allowing married women to have and administer their own savings accounts was introduced in 1900.[51] The women’s calm but assertive body language and their conspiratorial appearance show them to be self-confident femmes nouvelles, who consciously, and possibly through provocative behavior, break boundaries in order to assert their newly gained freedom in the public cultural sphere. This included visiting, alone or accompanied by a husband or a female friend, artists’ studios and (avant-garde) exhibitions as well as appearing at, and participating in, associated cultural events such as concerts, lectures, and semipublic salons.

Avant-Garde Exhibitions as Showcases of Sociability and Distinction

While the profusion of female amateurs represented in Belgian posters at the fin de siècle suggests that women became more present and visible in their relation to art during this period, it remains to examine to what extent and how women actually became actively engaged in the art scene. What position did they take in the art world, especially in the context of exhibitions of contemporary fine and decorative art? Where and how did they interact with artworks and artists? And how do the female amateurs represented in posters relate to women’s actual engagement with the arts and contemporary cultural life? In order to answer these questions, this section will take a closer look at textual and archival evidence and what this reveals about women’s actual presence at exhibitions and their involvement with avant-garde artistic circles in Brussels during the fin de siècle, thereby providing a wider sociocultural context for the posters in question.

The research of Brogniez and Gemis has shown that in Les XX and La Libre Esthétique, women, largely from the middle and upper-middle classes, were well represented and constituted about 30 percent of the audience at the exhibitions and other events, such as concerts and lectures as well as semipublic and private salons, organized by these associations.[52] Contemporary exhibition reviews and similar articles in newspapers and art journals confirm that during the 1890s, these events included an increasing number of women as integral members of their modern and fashion-conscious audiences in the Belgian capital. In February 1897, for example, the Brussels daily newspaper Le Petit Bleu du matin noted that the opening of the annual Salon of La Libre Esthétique had drawn “large crowds of people, ladies, artists and aesthetes with more or less long hair . . . a crowd so dense that it was impossible to look at a canvas, a bust or an art pottery.”[53] A similar trend was also observed with regard to other exhibitions associated with avant-garde movements, such as the annual shows of Pour l’Art—a Brussels art association created by the symbolist painter Jean Delville (1867–1953) in 1892. Following the opening of its first Salon, for example, the liberal newspaper L’Indépendance belge noted the “great attendance” at this event, in particular the presence of “many ladies.”[54] On the occasion of the opening of Pour l’Art’s second Salon, in January 1894, another journalist similarly noted that “in the midst of a fairly large crowd, . . . the ladies formed the majority: the usual elegant audience for this kind of ceremony.”[55]

Already in 1887, Belgian symbolist writer Georges Rodenbach (1855–98) had observed how modern art exhibitions were becoming preferred and fashionable social spaces for (young) women. In the journal Le Progrès, on the occasion of the opening of the fourth Salon of Les XX, he wrote:

Definitely this particular exhibition becomes an event in Brussels. A month in advance we chatter about it, we worry about it, we argue about it; young women have new outfits made for that day, the hunt for invitation cards begins, and it is a social solemnity which becomes fashionable to attend.[56]

Sharply analyzing the atmosphere at the Les XX exhibition and the audience’s sociocultural profile, Rodenbach noted:

We examine, we listen, we stop, we joke, and everyone there is having fun and seems to know each other. And in fact, everyone knows each other: it’s the Tout-Bruxelles artiste, the people who know the painters, who love Wagner and who put the latest Parisian novel on their coffee table.[57]

Rodenbach thus characterized the visitors at the Salons of Les XX as a (seemingly) coherent social group of modern art lovers—among which were many women—that sought not only aesthetic pleasure but also a certain social experience as well as cultural distinction. It was a social, cultural, and financial elite that distinguished itself by its progressivist taste and ideas, characterized by a “love for Wagner” and an interest in the latest trends in Parisian literature and culture.

That these artistic Salons were dominated by an atmosphere of self-fashioning and sociocultural distinction is also apparent in a review of the 1893 Salon of Les XX published in La Gazette. The reviewer was particularly struck by the “complete harmony that reigned between the bright colors of the modernist canvases displayed on the picture rail and those that the many ladies who were there and who never miss this little social event, had adopted for their clothing. It was only purple dresses and green veils, blue bodices with yellow sleeves, mauve coats and red hats.”[58] While the journalist’s elaborate description of the many female visitors’ fashionable attire seems to foreshadow Van Rysselberghe’s posters designed for the exhibitions of La Libre Esthétique some three years later (figs. 3, 25), it also hints at the character of these exhibitions. They were attended not only for the art but also—and perhaps especially—for their particular air of modernity and distinction, which set them apart from the larger and more commercial triennial Salons that were nevertheless also very social events.

Commenting on a concert that took place in the context of the same 1893 Salon of Les XX, a (presumably female) correspondent for the rather conservative newspaper Le Soir, writing under the pseudonym Corinne, likewise noticed not only that female visitors constituted the majority of the public but also that there was a strong similarity between the attendees and the painted figures on the exhibition walls:

The other day, at an exhibition of ultra-modernist painting, during a concert, . . . I took pleasure in looking at the curious picture formed by a brilliant audience where women, as always, were in the great majority, and comparing this picture to the bizarre compositions that decorated the walls. After a moment of contemplation, I no longer distinguished fiction from reality, and I vaguely sought an author’s name for each of my elegant neighbors, so striking was the resemblance between the people seated around me and the figures exhibited on the wall.[59]

Observing in particular the female visitors’ extravagant appearance—“their dresses which are veils, their sleeves which are wings, and their hats which are halos”—the correspondent described the women as “pre-Raphaelite angels according to their dress, and very modern in their appearance.”[60] That this is, however, not meant as a compliment becomes clear in the reviewer’s rather critical conclusion:

These were not portraits and their models; no, they were creatures of the same order, of the same essence, disturbing and indefinable, whimsical and chimerical, as seen in a hashish intoxication. . . . These incomprehensible paintings, daring and childish, pretentious and burlesque, seem made for the temple of some barbarous divinity, and the women who are inspired by them or who inspire them, however good bourgeois they may be at heart, contribute as much as this art, if not more, to the deprivation of manners and taste.[61]

The commentator for Le Soir thus demonstrates that the modernist fashions and social practices associated with the avant-garde exhibitions were by no means generally accepted but instead highly contested and subject to criticism from the more established bourgeoisie. At the same time, the aforementioned reviews all confirm the degree to which matters of fashionableness, exclusivity, and distinction were crucial to the functioning of avant-garde exhibitions. The flourishing of the avant-garde in Brussels, in fact, was in line with the emergence of specific discourses aiming to differentiate and justify the new forms of artistic expressions they promoted.[62] This discourse especially emphasized the anticommercial character of the art and the context in which it flourished, and the ideal of the close-knit social networks that supported it and that nourished ideas of exclusivity and aesthetic superiority. An article published in L’Art moderne in 1885 dedicated to the theme of “Les Esthètes” (The Aesthetes) sheds light on the functioning of this discourse. In the article, the aesthete is characterized as a true art enthusiast with an inner creative spirit of his own, for whom art is inseparable from life and who rejects the tastes and fashions dictated by commercial experts and dealers who operate in a circle detached from the actual artistic production of the moment.[63] During the 1890s, this theory was put into practice in, among other venues, Picard’s Maison d’Art, which was conceived as a place “established to promote, in a new and original form, private exhibitions, musical auditions, artistic conferences, purchases and sales of paintings and art objects, theatrical performances, outside from any spirit of mercantilism.”[64] The Brussels avant-garde thus particularly promoted the ideal of the artistic community as a close-knit network in which all participants—artists, collectors, and critics as well as truly devoted audiences—played a central role in the advancement of contemporary art and culture.

It is therefore not surprising that the catalogues of the Salons of Les XX and La Libre Esthétique provide the names of the patrons, collectors, and other owners of art who lent pieces to the exhibitions. Between 1884 and 1914, a few dozen women were also mentioned as lenders of contemporary French and Belgian paintings, some of them repeatedly, and were often referred to by their marital status as “madame” or “mademoiselle.”[65] That fin-de-siècle female amateurs owned or collected contemporary paintings rather than old masters seems to have been an international phenomenon.[66] There might have been various reasons for this preference, such as the artworks’ subjects, styles, formats, and decorative qualities as well as their lower prices, their availability, and their visibility in exhibitions and artists’ studios. At the same time, women’s increased access to the art press—which discussed contemporary art and as such influenced taste and collection choices—and the possible contact and dialogue it could stimulate with artists, also may have played a role. Finally, for some women, promoting and collecting works of contemporary art may have also served as a suitable means to distinguish themselves from fathers, husbands, brothers, or others collecting art by the old masters.

Artists that seem to have been particularly favored by Belgian women amateurs lending to Les XX and La Libre Esthétique were Georges Lemmen (1865–1916)—whose work was lent by at least six different women—and Van Rysselberghe—whose work was lent by at least five women, including Madeleine Gevaert (1874–1944), referred to as Mme Octave Maus. Both Lemmen and Van Rysselberghe, who were popular for their portraits, flowers, and interior scenes with women and children, executed in the pointillist style, were also closely involved in the organization of the Salons of Les XX—as committed vingtistes (members of The Twenty)—and La Libre Esthétique, together with Maus.[67] Their wives were also well acquainted. It also happened that the wives or widows or other close female relatives of male artists lent their work. While these women perhaps cannot be considered collectors in the true sense of the word, they nevertheless formed an important and recognizable group of female amateurs who sometimes supported specific artists.[68] It is clear that social networks were crucial for male as well as female amateurs: artists, patrons, and collectors were often close friends—and at times were relatives—owning each other’s works and lending them for exhibitions.[69] In 1914, a woman named as Mme L. Anspach lent to the Salon of the Libre Esthétique no less than nine paintings (mainly of flowers but also a nude) by Juliette Cambier (née Ziane; 1879–1963) from Brussels, who was a niece of Maus.[70] The work of Dario de Regoyos (1854–1913) and Xavier Mellery (1845–1921), who was much appreciated for his atmospheric symbolist interior scenes, also appealed to women art lovers.[71] Anna Boch (1848–1936), another niece of Maus and the only female vingtiste, rose to the forefront as a frequent exhibitor and lender at the Salons of Les XX and La Libre Esthétique. For eleven Salons, she lent works by fourteen French and Belgian artist-colleagues, including Constantin Meunier (1831–1905) in 1887; Emile Bernard (1869–1941) in 1893; Vincent van Gogh (1853–90) in 1904; Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) and Georges Seurat (1859–91) in 1904 and 1910; James Ensor (1860–1949) in 1905; and Paul Signac (1863–1935) in 1908.[72] A descendant of the wealthy Boch family, active in the earthenware and ceramics industry, Anna, who remained unmarried, became an influential figure within the avant-garde artistic network in fin-de-siècle Brussels. As of the 1880s, she was a distinguished hostess who organized exclusive salons, concerts, and choir recitals at her home—first located on the avenue de la Toison d’Or, where she was a neighbor of Picard, and after 1903 at rue de l’Abbaye in Ixelles, where she was a neighbor of Van Rysselberghe and Constantin Meunier.[73]

Avant-garde exhibitions and associated events such as concerts and lectures thus came to the fore as social events that functioned on the basis of tight social networks and that circulated around a largely consistent group of like-minded aesthetes, artists, and art lovers. It was this social coherence—in combination with a certain elitism and desire for distinction—that opened up new possibilities for women artists and amateurs to participate more actively in the art world.[74] Furthermore, this close-knit network and the corresponding sociability provided ideal conditions for female amateurs to inspire one another. Isabelle Goldschmidt (1869–1929), wife of the lawyer and Université Libre de Bruxelles professor Paul Errera (1860–1922), also regularly held musical salons that were attended by, among others, Boch and Maus.[75] In 1905, the young Antwerp writer and artist Emma Lambotte (née Protin; 1876–1963) referred to the impact that other women amateurs had on her in a letter to Ensor. She wrote how impressed she was by works of his that she had seen at the exhibition of La Libre Esthétique, and how much she had envied the owners of these paintings—notably Boch and Mariette Hannon (1850–1926) and her husband Ernest Rousseau (1831–1908)—for possessing them.[76] This experience would inspire Lambotte to assemble the largest private collection in Belgium of works by Ensor in the following decade.[77] Lambotte’s case shows the extent to which female amateurs drew on each other as role models and sources of inspiration. These women’s social and artistic activities gave them a presence and agency in the art world that was a new phenomenon in fin-de-siècle Brussels, one that is also reflected in—and was possibly encouraged by—the poster culture that flourished in precisely this same context.

Conclusion

A remarkable number of fin-de-siècle posters by Belgian artists advertising exhibitions of modern art, including posters, photography, and decorative arts, feature the new motif of the female amateur. In these posters—created with the aim of encouraging a wider public to visit the exhibitions—the female amateur appears as a modern, self-confident, and fashionable woman and a knowledgeable and critical viewer who is actively looking at and/or manipulating artworks. The female art lover—in the role of a museum or exhibition visitor accompanied by a husband, chaperone, or friend—also appears in other visual media, including paintings, created in Belgium during the last decades of the nineteenth century, attesting to the popularity of the motif as well as to the increasing presence and agency of women in these public spaces. Such paintings, however, usually show women as elegant “extras” in scenes focusing on the representation of a lavish museum interior full of artworks. In contrast, art nouveau posters from the 1890s by modern Belgian artists, especially those advertising exhibitions of modern art and avant-garde art circles, radically foreground the female amateur as the central figure, showcasing her as a fashionable and at times even provocative femme nouvelle who actively participates in the expanding cultural sphere of the fin de siècle. As such, the posters were a manifestation of the broader phenomenon—in Belgium as well as internationally—of women’s increased presence and participation in the art world as visitors to museums, exhibitions, galleries, and artists’ studios (a presence that was also frequently commented on in the contemporary press), and subsequently as amateurs, and as collectors and lenders of artworks to exhibitions.

This article suggests that it was, in particular, the exhibition venues associated with the Brussels avant-garde such as the Salons of Les XX and La Libre Esthétique—or rather the artists and organizers behind them—that played a pioneering role, in the 1890s, in noticing, identifying, and representing the figure of the modern female amateur, thereby reflecting the new visibility of women in the art world and further promoting it through the new medium of the exhibition poster. Thanks to their representation of women as active, fashionable, and highly engaged female amateurs, these posters thus constituted an intense and accessible means of echoing, endorsing, and encouraging women’s increased participation in the changing art and cultural scene in fin-de-siècle Brussels. However, while the posters do reflect an ongoing “feminization of art consumption,”[78] they are not necessarily indicators of a broader democratization of this particular art culture. Although the avant-garde networks and circles in fin-de-siècle Brussels seemed to have become more inclusive and open to women, they still remained rather elitist realms in which the experience of, and participation in, artistic events functioned as a means of social and cultural distinction.

Notes

All translations are by the authors unless otherwise noted.

[1] Isabel L. Taube, “William Merritt Chase’s Cosmopolitan Eclecticism,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 15, no. 3 (Autumn 2016), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2016.15.3.6.

[2] Ruth E. Iskin, The Poster: Art, Advertising, Design, and Collecting, 1860s–1900s (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2014), 82–83.

[3] Ruth E. Iskin, “The Material Culture and Gender of Print Connoisseurship in 1890s Paris,” in Making Waves: Crosscurrents in the Study of Nineteenth-Century Art, ed. Laurinda S. Dixon and Gabriel P. Weisberg (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2019), 109.

[4] Iskin, The Poster, esp. ch. 2.

[5] Iskin, The Poster, 82.

[6] Ruth E. Iskin, “Art Nouveau and the New Woman: Style, Ambiguity and Politics,” in Goddesses of Art Nouveau, ed. Wim Hupperetz and Martijn Akkerman, exh. cat. (Zwolle, the Netherlands: WBOOKS, 2020), 35–49; and Ruth E. Iskin, “Popularising New Women in Belle Époque Advertising Posters,” in A Belle Époque? Women and Feminism in French Society and Culture 1890–1910, ed. Diana Holmes and Carrie Tarr (Oxford and New York: Berghahn Books, 2006), 95–112.

[7] Iskin, “Popularising New Women in Belle Époque Advertising Posters,” 96.

[8] See, for example, Anne Pingeot and Robert Hoozee, eds., Paris-Bruxelles, Bruxelles-Paris: Réalisme, impressionnisme, symbolisme, art nouveau; Les Relations artistiques entre la France et la Belgique (Antwerp: Mercatorfonds, 1997); Jane Block, “Bruxelles-Paris: La Maison d’Art d’Edmond Picard et la galerie L’Art nouveau de Siegfried Bing,” in Siegfried Bing & La Belgique/België, ed. Virginie Devillez (Brussels: Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, 2010), 92–117; Debora Silverman, “‘Modernité sans Frontières’: Culture, Politics, and the Boundaries of the Avant-Garde in King Leopold’s Belgium, 1885–1910,” American Imago 68, no. 4 (2011): 707–97; Laurence Brogniez, Tatiana Debroux, and Judith Le Maire, “The Rise of a Small Cultural Capital: Brussels at the End of the 19th Century,” in Other Capitals of the Nineteenth Century: An Alternative Mapping of Literary and Cultural Space, ed. Richard Hibbitt (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 129–57; and Debora Silverman, “Boundaries: Bourgeois Belgium and ‘Tentacular’ Modernism,” Modern Intellectual History 15, no. 1 (2018): 261–84.

[9] The term animateur d’art denotes a mediator figure in the art world who can assume multiple roles, such as editor, publisher, critic, dealer, connoisseur, amateur, and collector. See Ingrid Goddeeris and Noémie Goldman, eds., The Animateur d’Art and His Multiple Roles: Pluridisciplinary Research of These Disregarded Cultural Mediators of the 19th and 20th Centuries (Brussels: Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, 2015).

[10] See, for example, Paul Aron and Cécile Vanderpelen-Diagre, Edmond Picard (1836–1924), un bourgeois socialiste belge à la fin du dix-neuvième siècle: Essai d’histoire culturelle (Brussels: Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, 2013).

[11] See Laurence Brogniez and Vanessa Gemis, “Les femmes, les XX et La Libre Esthétique: Entre ombre et lumière,” in Bruxelles, convergence des arts (1880–1914), ed. Malou Haine and Denis Laoureux (Paris: Vrin, 2013), 227–47; and Laurence Brogniez and Tatiana Debroux, “Une exposition à l’échelle de la ville: Sociabilités des espaces complémentaires aux Salons des XX et de La Libre Esthétique,” COnTEXTES. Revue de sociologie de la littérature, no. 19 (2017), http://journals.openedition.org/contextes/6327.

[12] See, for example, the posters designed by Gisbert Combaz for the Salons of La Libre Esthétique of 1897, 1898, 1899, and 1901.

[13] Brogniez and Gemis, “Les femmes, les XX et La Libre Esthétique,” 343.

[14] On Belgian posters, see, for example, Yolande Oostens-Wittamer, De Belgische affiche 1892–1914 (Brussels: Koninklijke Bibliotheek Albert I, 1975); and Jane Block, Homage to Brussels: The Art of Belgian Posters (1895–1915), exh. cat. (New Brunswick: Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 1992). Ernest Maindron’s Les Affiches illustrées, 1886–1895 (Paris: Boudet, 1896) features numerous designs by Belgian artists.

[15] “L’effet auquel il arrive par la juxtaposition de tons plats, par la synthèse des lignes essentielles est vraiment prodigieux.” “Les Arts décoratifs au Salon des XX,” L’Art moderne, February 26, 1893, 66.

[16] Brogniez and Debroux, “Une exposition à l’échelle de la ville.” See also Laurence Brogniez and Tatiana Debroux, “Les XX in the City: An Artists’ Neighborhood in Brussels,” Artl@s Bulletin 2, no. 2 (2013): 38–51.

[17] “nous ne perdons aucun espoir de voir un jour les rues de Bruxelles se faire les musées de belles œuvres étalées au plein air.” “L’Affiche,” L’Art Moderne, February 19, 1893, 58.

[18] “Mais pour cela il faut que les organisateurs de fêtes et de kermesses . . . confient l’exécution des affiches à d’autres qu’à de vieilles badernes ou des rapins de vingtième ordre.” “L’Affiche,” L’Art moderne, February 19, 1893, 58.

[19] On the diverse poster exhibitions held in Brussels during the 1890s, see Block, Homage to Brussels.

[20] Jane Block, “La Maison d’Art: Edmond Picard’s Asylum of Beauty,” in Irréalisme et Art Moderne: Mélanges Philippe Roberts-Jones, ed. Michel Draguet (Brussels: Université Libre de Bruxelles, 1991), 145–62; Block, “Bruxelles-Paris: La Maison d’Art d’Edmond Picard,” 112; and Paul Aron, “‘La Maison d’art’ d’Edmond Picard: Ongesien kan geschien. Un avocat esthète et collectionneur,” in Genius, grandeur & Gêne: Het fin de siècle rond het Justitiepaleis te Brussel en de controversiële figuur van Edmond Picard, ed. Willy van Eeckhoutte and Bruno Maes (Herentals, Belgium: Knops, 2014), 187–200.

[21] “À la Maison d’art. Exposition d’affiches françaises et belges,” L’Art moderne, May 17, 1896, 157.

[22] Iskin, “The Material Culture and Gender of Print Connoisseurship,” 111; and Deborah Silverman, Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siècle France: Politics, Psychology, and Style (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), ch. 4. On the changing conditions for women in fin-de-siècle Belgium, see, for example, Gita Deneckere, 1900: België op het breukvlak van twee eeuwen (Tielt, Belgium: Lannoo, 2006), 165–81.

[23] Iskin, “The Material Culture and Gender of Print Connoisseurship,” 109.

[24] The painting entered the Louvre in 1869 via the bequest of Louis La Caze. The original has a somewhat wider format and shows a larger portion of the woman’s left sleeve than the version represented in Vanaise’s painting.

[25] We refer here to Michael Fried’s Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980).

[26] Kate Hill, Women and Museums, 1850–1914: Modernity and the Gendering of Knowledge (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2016), 103–26. On the changing accessibility and audiences of Belgian museums, see Liesbet Nys, De intrede van het publiek: Museumbezoek in België, 1830–1914 (Leuven, Belgium: University Press Leuven, 2012).

[27] This statue is still in the museum collection today. When Eugène Bertrand (1858–1934) painted in 1886 the visit of two bourgeois women to the same museum, a little guide in hand, he made them look up at a statue of a nude woman (Le Hall d’entrée du musée à Bruxelles [The Entrance Hall of the Museum in Brussels], Museum of Ixelles, Brussels). Michèle Van Kalck, ed., De Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België: Twee eeuwen geschiedenis, vol. 1 (Brussels: Dexia Bank-Lannoo, 2003), 292. On p. 301 is an engraving by Louis Titz of yet two other bourgeois women visiting the Brussels museum around 1900.

[28] The authoritative nineteenth-century catalogue of the Antwerp Museum of Fine Arts was written by Théodore Van Lerius and first published in 1857. See Barbara Caen, “Catalogues from Johan De Laet up to Pol De Mont (1845–1905),” in The Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp: A History; 1810–2007, ed. Leen De Jong et al. (Oostkamp, Belgium: Stichting Kunstboek, 2008), 214–15. During the nineteenth century, the compilation of collection catalogues remained principally a male domain, even though women were active in different branches of art writing and criticism. On the interrelated topic of female art writing, connoisseurship, and criticism, see “Old Masters, Modern Women,” special issue, 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, no. 28 (2019); “Women’s Expertise and the Culture of Connoisseurship,” ed. Meaghan Clarke and Francesco Ventrella, special issue, Visual Resources 33, no. 1–2 (2017); and Meaghan Clarke, “The Art Press at the Fin de Siècle: Women, Collecting, and Connoisseurship,” Visual Resources 31, no. 1–2 (2015): 15–30.

[29] For a detailed discussion of Fernand Fau’s poster, see Iskin, “The Material Culture and Gender of Print Connoisseurship,” 110.

[30] Benoît Schoonbroodt, Privat-Livemont: Entre tradition et modernité au coeur de l’Art Nouveau (Brussels: Racine, 2007), 22.

[31] A quasi-identical woman features in a set of twelve illustrated, color lithographed postcards entitled Leurs Gestes (Leonard A. Lauder Poster Archive, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), published in Brussels by Dietrich & Co. around 1900, once mirror-inverted and without the display case in the title card, and once looking at prints in the display case, demonstrating that this imagery was literally and figuratively widespread.

[32] See Iskin, “The Material Culture and Gender of Print Connoisseurship.” See also Ruth E. Iskin and Britany Salsbury, eds., Collecting Prints, Posters and Ephemera: Perspectives in a Global World (New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020).

[33] The exhibition is discussed in Roland de Marès, “Le Sillon,” L’Art moderne, October 11, 1896, 323.

[34] The exhibition closed on January 22, 1899. See L’Art moderne, January 22, 1899, 4.

[35] On this topic, see Marjan Sterckx, “Sculpture and the Decorative in Fin-de-Siècle Brussels: Women as Consumers and Creators,” in Sculpture and the Decorative in Britain and Europe, Seventeenth Century to the Contemporary, ed. Imogen Hart and Claire Jones (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020), 113–24. Occasionally, the motif also appears in other formats, such as Louise Danse’s (1867–1948) Portrait of a Woman, an undated etching in the Museum Plantin-Moretus in Antwerp, featuring a woman scrutinizing a statuette held in her hands.

[36] For an analysis of selected posters advertising such consumer goods as cigarettes, salad oil, and bicycles, see Iskin, “Art Nouveau and the New Woman,” esp. 38–46.

[37] Manuel Charpy, “Patina and the Bourgeoisie: The Appearance of the Past in Nineteenth-Century Paris,” in Surface Tensions: Surface, Finish and the Meaning of Objects, ed. Glenn Adamson and Victoria Kelley (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2013), 49. On touch as related to artistic artifacts and gender, see, for example, Constance Classen, The Deepest Sense: A Cultural History of Touch (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012) 132–46; and Peter Dent, ed., Sculpture and Touch (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2014).

[38] “Quelques faïences à reflets métalliques sorties des fours de la Manufacture de Hasselt . . . complètent l’exposition. . . . Et vraiment, le résultat est stupéfiant.” See “À la Maison d’art. Exposition d’affiches françaises et belges,” 157.

[39] “La Maison d’art . . . réalise le type d’un établissement privé destiné à favoriser la liberté et le progrès des Arts dans toutes leurs manifestations contemporaines.” See the advertisement for “La Maison d’art de Bruxelles,” L’Art moderne, November 5, 1899, 375.

[40] “Pour la première fois, on exhibira les objets d’art dans leur atmosphère, sous le jour pour lequel ils ont été créés, avec leur destination spéciale.” “Les industries d’art,” L’Art moderne, October 21, 1894, 332.

[41] Block, “Bruxelles-Paris: La Maison d’Art d’Edmond Picard,” 112; Sterckx, “Sculpture and the Decorative,” 117; and Ulrike Müller and Marjan Sterckx, “Art and Domestic Space: Continuity and Change in Private Collectors’ Interiors in Belgium, ca. 1830–1930,” in Domestic Space in France and Belgium: Art, Literature and Design (c. 1850–1920), ed. Claire Moran (London: Bloomsbury, 2022), 62–63.

[42] “Il aboutira, sans doute, . . . à la formation d’une compagnie esthétique compacte.” “Comment vivra la Maison d’art,” L’Art moderne, December 5, 1895, 387. See also Aron and Vanderpelen-Diagre, Edmond Picard, 198.

[43] “L’ameublement, le papier peint, la céramique, la verrerie, le Livre, la reliure, la ferronnerie . . . y seront montrés dans leur cadre et non plus dans le décor banal d’une salle d’exposition.” “Les industries d’art,” 332.

[44] On this poster, see also Iskin, “Art Nouveau and the New Woman,” 44.

[45] See “L’Affiche,” L’Art moderne, February 19, 1893, 57.

[46] On Toulouse-Lautrec’s influence on Van Rysselberghe and other Belgian poster artists, see Iskin, The Poster, 98.

[47] On this poster, see also Sterckx, “Sculpture and the Decorative,” 115–19.

[48] A work with a similarly erotic subject is the painting Curiosité (Curiosity), exhibited in 1894 at the Universal Exhibition in Antwerp by the Hungarian artist Gyula Stetka (1855–1925), picturing a woman looking at a print of a nude whose gender cannot be discerned. Behind her is a curious man with an amused expression, peering through an open window at both the print and the woman looking at it.

[49] See, for example, L’Art moderne, February 21, 1897, 63. See also Sterckx, “Sculpture and the Decorative,” 118–19.

[50] See also Iskin, “Art Nouveau and the New Woman,” 40.

[51] Sabine Van Cauwenberge and Leen De Jong, “Vrouwelijke kunstenaars in België van 1800–1950,” in Elck zijn waerom: Vrouwelijke kunstenaars in België en Nederland 1500–1950, ed. Katlijne Van der Stighelen and Mirjam Westen (Gent: Ludion, 1999), 68–87; and Annemie Vanthienen, “De eerste feministische golf in België,” RoSa Fact Scheets, no. 28 (2003): 4. On the history of women’s emancipation in Belgium, see also Hedwige Peemans-Poullet, Femmes en Belgique, XIXe–XXe siècles (Brussels: Université des Femmes, 1991); and Monika Triest, Wat zoudt gij zonder ’t vrouwvolk zijn? Een geschiedenis van het feminisme in België (Antwerp: Uitgeverij Vrijdag, 2018). Clarke and Ventrella note that women’s access to a university was not a necessity for developing connoisseurship: “The lack of an academic discourse for art history in Britain until the 1930s entailed that connoisseurship was practiced mostly outside academia, which meant that women could develop their expertise in spite of having restricted access to universities.” “Women’s Expertise and the Culture of Connoisseurship,” 1.

[52] Brogniez and Gemis, “Les femmes, les XX et La Libre Esthétique”; and Brogniez and Debroux, “Une exposition à l’échelle de la ville.”

[53] “Grande affluence de monde, de dames, d’artistes et d’esthètes aux cheveux plus ou moins longs; gracieux caquetages mondains, mais foule tellement dense qu’il était impossible de regarder une toile, un buste ou une poterie d’art.” “A travers la ville,” Le Petit Bleu du matin, February 26, 1897, 1.

[54] “grande affluence de monde, et beaucoup de dames.” “Au jour le jour. Échos de la ville,” L’Indépendance belge, November 14, 1892, 1.

[55] “au milieu d’une affluence assez considérable, . . . les dames formaient la majorité: l’élégant public habituel de ce genre de cérémonies.” “Faits divers. Pour l’Art,” La Meuse, January 15, 1894, 3.

[56] “Décidément cette exposition particulière devient un événement dans Bruxelles. Un mois à l’avance on en jacasse, on s’en préoccupe, on en dispute; de jeunes femmes font faire des toilettes neuves pour ce jour-là, la chasse aux cartes d’invitation commence, et c’est une solennité mondaine à laquelle il devient de bon ton d’assister.” Georges Rodenbach, “Tête de vingtistes,” Le Progrès, February 10, 1887, n.p.

[57] “Enfin l’ouverture a lieu: quel bruit, quelle cohue, quels croisements de regards et de voix. On examine, on écoute, on s’arrête, on plaisante, et tout le monde, là, s’amuse et semble se connaître. Tout le monde se connaît en effet: c’est le Tout-Bruxelles artiste, les gens qui connaissent les peintres, qui aiment du Wagner et mettent sur leur guéridon le dernier roman de Paris.” Rodenbach, “Tête de vingtistes,” n.p.

[58] “Si vous y étiez, vous avez dû être frappé par l’harmonie complète qui régnait entre les couleurs vives des toiles modernistes s’étalant à la cimaise et celles que les nombreuses dames qui se trouvaient là et qui ne manquent jamais ce petit événement mondain, avaient adoptées pour leurs toilettes. Ce n’étaient que robes violettes et voilettes vertes, corsages bleus à manches jaunes, manteaux mauves et chapeaux rouges.” X, “Le Salon des XX,” La Gazette, March 20, 1893, cited in Brogniez and Gemis, “Les femmes, les XX et La Libre Esthétique,” 344.

[59] “L’autre jour, à une exposition de peinture ultra-moderniste, pendant un concert, . . . je pris plaisir à regarder le curieux tableau formé par un brillant auditoire où les femmes, comme toujours, étaient en grande majorité, et à comparer ce tableau aux bizarres compositions qui décoraient les murs. Au bout d’un instant de contemplation, je ne distinguais plus la fiction de la réalité, et je cherchais vaguement un nom d’auteur pour chacune de mes élégantes voisines, tant la ressemblance était frappante entre les personnes assises autour de moi et les figures exposées sur la cimaise.” Corinne [pseud.], “Mon jour. L’Art et les femmes,” Le Soir, March 16, 1893, 1.

[60] “avec leurs robes qui sont des voiles, leurs manches qui sont des ailes, et leurs chapeaux qui sont des nimbes; anges préraphaélites par le costume et bien modernes par la physiognomie.” Corinne, “Mon jour,” 1.

[61] “Ce n’étaient pas des portraits et leurs modèles; non, c’étaient des créatures de même ordre, de même essence, troublantes et indéfinissables, fantasques et chimériques, comme vues dans une ivresse de haschisch. . . . Ces peintures incompréhensibles, audacieuses et enfantines, prétentieuses et burlesques, semblent faites pour le temple de quelque divinité barbare, et les femmes qui s’en inspirent ou qui les inspirent, si bonnes bourgeoises peut-être qu’elles soient dans le fond, contribuent autant que cet art, sinon davantage, à la déprivation des mœurs et du goût.” Corinne, “Mon jour,” 1.

[62] See Noémie Goldman, “Un monde pour les XX. Octave Maus et le groupe des XX: Analyse d’un cercle artistique dans une perspective sociale, économique et politique” (PhD diss., Université Libre de Bruxelles, 2012). On the discourses that flourished in the networks of the artistic avant-garde and that especially promoted the concepts of individualism, artistic independence, freedom of aesthetic judgment, and anti-commercialism, see Robert Jensen, Marketing Modernism in Fin-de-Siècle Europe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994).

[63] “Les Esthètes,” L’Art moderne, September 13, 1885, 296–98.

[64] “La Maison d’art . . . établie pour favoriser, sous une forme nouvelle et originale, les expositions privées, les auditions musicales, les conférences artistiques, les achats et les ventes de tableaux et objets d’art, les représentations théatrales, en dehors de tout esprit de mercantilisme.” Advertisement for “La Maison d’art de Bruxelles,” L’Art moderne, November 5, 1899, 375.

[65] Le Salon des “XX” et de La Libre Esthétique: Répertoire des exposants et liste de leurs œuvres; Bruxelles, 1884–1914, ed. Pierre Sanchez (Dijon: L’Échelle de Jacob, 2012), 49–56 (“Index des collectionneurs”).

[66] See, for example, Clarke, “Art Press,” 23.

[67] Le Salon des “XX” et de La Libre Esthétique, 49–56, 254–58, 390–91. Lemmen himself also lent works to the Salons of Les XX.

[68] Examples are Cornelia van Hove, also known as Mme Charles Van der Stappen; Mlle Anna Verheyden (daughter of Isidore Verheyden); and Mme [Louise] Van Mattemburgh, lender in 1905 of work by Henri Evenepoel, her deceased cousin, and the mother of their son Charles. Work by Evenepoel was also owned and lent by a woman identified as Mme S. Fraikin. A woman identified as Mme S., who lent work by Charles Samuel in 1897; another identified as Mme O. D., who lent a painting by the Brussels painter Paule(tte) Deman in 1907; and a third identified as Mme H. S., who lent a work by Paul Signac in 1893, perhaps were the mothers of Samuel, Deman, and Signac, respectively. Other examples of French women who lent work to the Brussels Salons are Mme [Georges] Seurat, Mme Eugène Carrière, and Mme Henri-Edmond Cross. Le Salon des “XX” et de La Libre Esthétique, passim.

[69] Notably, Maria Monnom, also known as Mme Théo Van Rysselberghe, lent a drawing by Georges Lemmen in 1893 to the Salon of Les XX; and Mlle Maréchal, who lent Roses by Lemmen to the 1905 Salon of La Libre Esthétique, had already been portrayed by the artist in a work exhibited at the Salon of Les XX of 1892. See Le Salon des “XX” et de La Libre Esthétique, passim.