Dressing Up: The Women Who Influenced French Fashion by Elizabeth L. Block

Reviewed by Elizabeth CarlsonElizabeth Carlson

Assistant Professor of Art History, Lawrence University

Email the author: elizabeth.carlson[at]lawrence.edu

Citation: Elizabeth Carlson, book review of Dressing Up: The Women Who Influenced French Fashion by Elizabeth L. Block, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 21, no. 3 (Autumn 2022), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2022.21.3.15.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

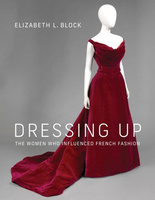

Elizabeth L. Block,

Dressing Up: The Women Who Influenced French Fashion.

Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 2021.

296 pp.; 71 color and 19 b&w illus.; bibliography; notes; index.

$34.95 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978–0–2620–4584–1

Elizabeth L. Block’s book Dressing Up: The Women Who Influenced French Fashion is an innovative examination of French fashion from the perspective of elite clientele in the United States. She convincingly argues that wealthy women played an integral role in the transnational exchange of high-end fashion during the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century. Block opens a new area of inquiry within a well-researched topic by disrupting two assumptions in the current scholarship. Dressing Up challenges the concept of the couturier as genius and instead positions the consumer as active participant, rather than passive consumer, in the French fashion industry. These consumers acted as “influencers within the system” (14) who helped to determine designs and trends. Thereby, Block shifts the focus to see the designer as “just one of the participants in the broader system” (5). Secondly, Block shows that fashion wasn’t solely moving from Paris outward but that US clientele, both wealthy socialites and celebrities, influenced the most famous Parisian houses of fashion—Charles Frederick Worth, Jacques Doucet, Maison Félix, and Jeanne Paquin. As Block concludes the introductory chapter, “the book seeks to change our conception of the power sources within the complex, transnational fashion industry” (14).

Block builds upon the more recent scholarship of Yuniya Kawamura, Joanne Entwistle, and Elizabeth Wilson, all of whom look at the theory and sociology of fashion, but also on the work of Heidi Brevik-Zender, Louise Crewe, and John Potvin, who examine the relationship between fashion and space and place. As Block writes, the guiding principle of the book is to “‘follow the dress,’ a tack that opens onto an analysis of labor, gender, space, and performance and the ways in which they relate to fashion” (4). This idea directs each chapter, focusing on individual dresses and patrons, understanding that the biographies of the material object and the consumer offer as much insight into the French fashion industry as the designers themselves. Maison Félix is used throughout the book as a lens through which to view the influence of French fashion on US women and their patronage. As Block asserts in the introductory chapter of the book, the existing scholarship is skewed towards Worth because the company is well documented, and the archives are more complete. Block offers a more complete picture by examining Félix, whose name was commonplace in the United States and whose company relied on US patrons. Block recovers the importance of Maison Félix in the French fashion industry, along with more recognizable names, such as Doucet and Paquin. To that end, she devotes two chapters to Maison Félix to track its success and abrupt closure in 1901. To emphasize the collaborative process between the customers and designers, the book is sprinkled with anecdotes about the dresses themselves and the women who bought and wore them, which are culled from letters, photographs, and promotional material.

Dressing Up is divided into three parts. Part I, “Power Dressing,” establishes Parisian fashion as a transnational industry and sets up the connection between French fashion and US consumers. This chapter shows that there was a long history of French imports being sold in department stores in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, and other urban centers throughout the nineteenth century. For example, A. T. Stewart and Lord and Taylor sold French fabrics, and department stores in the United States regularly sent buyers to Paris, some even opening Parisian offices. The chapter also shows that these foreign fashions were widely advertised throughout the United States, familiarizing their audience with French fabrics and designs.

Part II, “Paris as the Center of Haute Couture and Coiffure,” offers a history of the Parisian fashion industry, providing examples from an array of fashion houses and looking more holistically at the relationship between hair, perfume, and fashion. Chapter 3 introduces the book’s most original and significant contribution. Supporting the argument that fashion is a broad system, this chapter highlights the collaboration between hair, perfume, and dress, connections usually overlooked in the scholarship. Couturiers collaborated with coiffeurs and perfumers to create a full ensemble. The chapter opens with a cover illustration from Harper’s Bazar displaying a hairstyle from Lenthéric and a dress from Worth, revealing how each designer relied on the other. Milliners were informed by the latest hairstyles and dress designers looked to perfumeries to add scent to their dresses. Individual women created their signature scents with sachets sewn into their dresses. One’s identity was constructed by both one’s scent and specific sense of fashion. Block importantly pinpoints the relationship between the two, showing the multi-sensory performative experience of fashion in the latter half of the nineteenth century. This case study also demonstrates the influence of US clientele on French trends. An illustration for the hairdresser Lenthéric shows the salon offering two ways of shampooing—United States (with water) and French (without water)—revealing the influence of US practices in Paris. Chapter 4 investigates the role of International Expositions, which were important venues for showcasing fashions, hairstyles, and perfumes to an international clientele. While the houses of Paquin and Worth grew after the Paris 1900 Exposition, Maison Félix collapsed into bankruptcy shortly after. Chapter 5 reconstructs the transnational clientele by looking at individual patrons within the system. Studying specific personalities, such as Caroline Astor and Berthe Honoré Palmer, we learn of the fashions they preferred, how they used fashion, and the high prices they were willing to pay. Royalty, actresses, singers, and socialites used their knowledge of fabrics and designs and the acquisition of exclusive brands as cultural capital. Fashion even served as a strategic diplomatic tool in marriages between royal Europeans and women from the United States.

Part III, “The U.S. Market for French Fashion,” looks at how consumers used French fashion in the United States. Chapter 6 returns to an analysis of Maison Félix as a case study and offers anecdotes of the company’s business practices and patrons, proving that transnational patronage was integral to the success of the company. Chapter 7 focuses on the elaborate balls hosted by wealthy women in the United States, for which Parisian couture houses were often commissioned to design costumes. Block argues that these dresses “activated newly built homes,” filling them with the “cachet of Parisian couture” (135). Looking specifically at designs worn at costume balls, Block demonstrates how the whole environment was integrated with French fashions, bringing credibility to new money as the designs often mimicked French royalty. Chapter 8 turns to economics, revealing how significant taxes from the US government (specifically the McKinley Tariff of 1890 and the Dingley Tariff of 1897) encouraged wealthy women to buy locally made fashions, limiting the import of French designs. The final chapter examines how exorbitant prices led to both smuggling and counterfeit French couture. US designers copied these fashions and even sewed fake labels into the clothing. While some fashion houses directly fought these counterfeits, other houses like Worth sold department stores the right to copy their designs. In addition to reproductions, Block introduces the emergence of another market for French fashions as they were frequently repurposed with a new bodice or a new cut. Even though these women could most likely afford new dresses, they chose to recycle them. The final chapter demonstrates, once again, the US consumer as an active and collaborative participant in the transnational fashion system.

Dressing Up is widely accessible, clearly written, engaging, and thoroughly researched. Block incorporates a variety of archival sources from international exhibitions, advertisements, photographs, and private letters, most of which center the perspective of the consumer. These various anecdotes support the book’s larger argument and immerse the reader into the narratives of the wealthy clientele and the dresses that are threaded throughout the text. The book’s illustrations render the experience of reading it still more rewarding. Combined with the careful and colorful descriptions of the individual dresses, the images bring the dresses to life. Block brings to individual dresses the careful observation and creative interpretation usually reserved for paintings or sculpture. It is especially rewarding to see the side-by-side comparison of the dresses themselves and an artist’s rendering of the same dress or a historical photograph of an individual wearing the same dress. Such comparisons emphasize the cultural capital inherent in these designs and the importance of preserving them in paint.

The book ends rather abruptly with an unsatisfying conclusion. The broad scope of the book with its various threads would benefit from a more thorough analysis, returning to some of the case studies to weave them together and perhaps answer some lingering questions. What were the broader implications of the influence women from the United States had on French designs and the international market? How did power dynamics between French couturiers and their US clientele shift in the early twentieth century? Did any US houses of couture effectively compete with French ones?