Théodore Rousseau and the Rise of the Modern Art Market by Simon Kelly

Reviewed by Kelly PresuttiKelly Presutti

Assistant Professor

Cornell University

Email the author: kmp275[at]cornell.edu

Citation: Kelly Presutti, book review of Théodore Rousseau and the Rise of the Modern Art Market by Simon Kelly, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.1.14.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Simon Kelly,

Théodore Rousseau and the Rise of the Modern Art Market.

London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021.

250 pp.; 8 color and 64 b&w illus.; notes; 3 appendices; bibliography; index.

$120 (hardcover)

ISBN: 9781501343797

In his deeply researched account of Théodore Rousseau’s (1812–67) dealings with the art market, Simon Kelly cites a letter from Rousseau’s companion Jean-François Millet (1814–75). “Power is power from the very beginning,” Millet writes (75). The artist was speaking of painterly prowess, but he could just as well have been referring to Rousseau’s financial and social capital. The Rousseau who emerges from Kelly’s study may have cultivated a public image as a Romantic outlaw worshipping the woods, but he was equally a savvy player who befriended powerful elites, amassed and spent vast amounts of money, and carefully controlled the legacy he would leave behind.

Kelly seeks to reconcile this seeming contradiction in a book that draws on decades of scholarship and work as a curator. He sees Rousseau’s outsider identity as central, rather than counter, to the artist’s engagement with the market. In this, Kelly finds Rousseau anticipating contemporary realities in which artists have to self-promote even as their work attempts to critique the very system that supports them. Rousseau may not have been as tongue-in-cheek as, say, Jeff Koons’s inflation-proof balloons, but Kelly shows he was pulling just as many strings at a moment when the modern art market was still in formation.

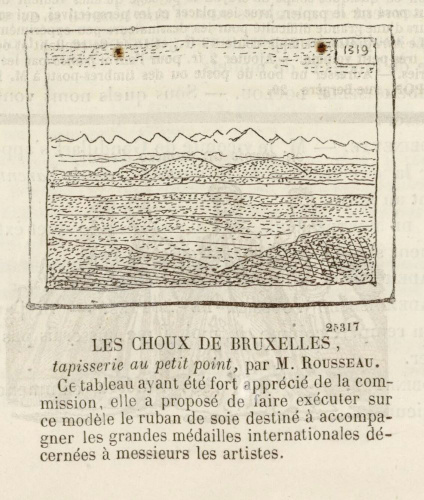

The first chapter outlines Rousseau’s relationship to the Salon, the point of origin for his “outlaw” identity. Rousseau is famously referred to as “le grand refusé” for all the rejections he received from that bastion of official culture. But Kelly corrects the record, pointing out that despite six refusals, Rousseau exhibited at the Salon both early in his career and every year but one from 1849 until his death in 1867. Kelly details the kind of work Rousseau sent for submission as his style evolved and the probable reasons for its refusal given the conservative makeup of the jury in the 1830s and 40s. He also shows how Rousseau managed to craft a public identity anyway, in part through the support of critics, including Théophile Thoré (1807–69). Thoré often mentioned the artist in his Salon reviews despite Rousseau’s absence from the exhibition. Though his work went unseen in 1844, Thoré affirmed in his review of that year’s Salon that Rousseau was “our leading landscape painter” (25). Thoré continued to help the artist shape his identity with a series of articles in 1847 that recounted an overnight trek the two took through the Fontainebleau forest. The critic relayed the quasi-mystical sentiments expressed by his companion as they experienced “a sort of ecstasy” given the beauty of the woods; Thoré then read that mysticism back into the artist’s depictions of nature (27). Kelly, too, links Rousseau’s persona to his painting, arguing that in more stylistically innovative works “technical audacity came together with his outsider identity to signal artistic ‘authenticity’” (30). That such audacity was the subject of critical ridicule, as in a caricature comparing his painting to a tapestry of brussels sprouts (fig. 1), only further contributed to Rousseau’s mythologized persona.

Chapter 2 shows how Rousseau made his career exhibiting outside of the Salon and in so doing provides a history of alternative exhibition spaces in nineteenth-century Paris and beyond. The studios of friends like Ary Scheffer (1795–1858), artists’ societies, regional exhibitions, and private clubs all provided opportunities for Rousseau to cultivate an audience and entice buyers. Kelly considers the works shown in each venue, demonstrating how carefully Rousseau was tailoring his work to his audience. In a classic example of presumed provincial stereotypes, the artist chose to send a more “finished” painting to an 1851 exhibition in Bordeaux, as opposed to the experimental sketches he was showing in Paris. “The Bordelais will thank me,” he wrote, “for showing a good deal of discretion in this regard” (69). Rousseau was strident when works were chosen without his oversight; for the 1860 Belgian Salon in Brussels, he wrote to express his displeasure that paintings had been sent without his approval and insisted they exhibit only the work he had finished “specially” [Rousseau’s underlining] for the show (70). Rousseau’s most important exhibition was his 1867 retrospective at the Cercle des Arts, an exclusive arts club on the rue de Choiseul. A summation of thirty-five years of work, with an accompanying catalogue by Philippe Burty (1830–90) to which Rousseau himself likely contributed, the show traced both the evolution of Rousseau’s work and the significance of studies to his overall oeuvre. As what Kelly terms “a key example of a monographic retrospective of an avant-garde painter,” the Cercle provided a way for Rousseau to market his preparatory studies and served as a precedent for the subsequent popularity of solo exhibitions as a means of surveying an individual artist’s oeuvre (82).

We come to know Rousseau’s patrons in the third chapter. From the early support of the duc d’Orléans (1810–42) to the backing of the banker Paul Périer (1812–97) and the later close relationship with industrialist Frédéric Hartmann (1822–80), Rousseau had an influential group of supporters. These figures provided a steadying force against the fluctuations of an emerging art market. While Kelly is keen to show that Rousseau nevertheless managed to preserve his independence, the artist was undoubtedly bound to occasionally provide, for example, “that small variety that you desire on a cow” in response to a dealer’s demands (136). Rousseau’s resistance often came in the form of a refusal to deliver, holding on to paintings in his studio as he worked and reworked them. Hartmann wrote Rousseau repeatedly in the 1850s to request delivery of a commissioned painting, Farm in the Landes (ca. 1852–67, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown). Rousseau defended his protracted process as one of “serious thought and study,” despite being “out of tune with the rapidity of production of our age” (106). Rousseau’s rhetoric managed to raise the price of that painting to 9,000 francs—three times the agreed upon amount—without ever delivering it. He may have been working the patron as much as the picture, claiming, when Hartmann suggested Rousseau may want to sell the work to another collector, that to do so “would remove all the intimacy that has built up between us over time” (106). Hartmann’s “intimacy” with Rousseau extended to nearly 100,000 francs over the course of their relationship in both purchases and unrepaid loans.

Rousseau also worked closely with dealers, as Kelly describes in chapter 4. While initially reluctant to engage so directly with the market, by the 1850s Rousseau took advantage of the growing number of commercial dealers in Paris—the city boasted 102 by 1858 (132). Kelly usefully catalogues an impressive network of art dealers and gallerists and shows how Rousseau strategically worked with at least ten of them to negotiate increasingly higher prices for his paintings. Rousseau, it may be surprising to read, was earning rates comparable to Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) for paintings of similar sizes and was making more than Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875) through the 1850s (137). Higher prices corresponded to an increased production of paintings of what Rousseau’s biographer Alfred Sensier (1815–77) termed “simple, elementary motifs” including “copses, attractive plains, and pretty villages” that would be pleasing to his public (137). In explaining Rousseau’s appeal to a growing market, Kelly’s argument parallels Anne Wagner’s analysis of Gustave Courbet’s (1819–77) landscapes, which Kelly references in his introduction. Wagner found the very form of Courbet’s landscapes to be dictated by their buyers, as beleaguered bourgeois urbanites took refuge in an effect of paint they might call nature. Wagner pointed out that, at least in the nineteenth century, “commercial and critical success in one genre [landscape] did not stifle the controversy and threat of the other [socially engaged painting].”[1] Kelly similarly remarks that “[Rousseau’s] engagement with the commercial sphere provided him with the financial security to produce other work that was more inventive” (138).

Rousseau’s “more inventive” production included a heavily worked style Kelly terms “proto pointillist,” as in the stippled surface of The Rock Oak (Forest of Fontainebleau; fig. 2). These paintings were poorly received at the time, but they shine in Kelly’s ekphrasis. Throughout the book, Kelly’s familiarity with both Rousseau’s paintings and the process by which they were made makes for especially compelling description. For Kelly, the foliage of The Rock Oak is not just green but “a range of pigments from viridian to emerald green,” applied in “repetitive, stippled marks” to create “an effect of all-over flatness and semi-abstraction” (40). That Rousseau’s contemporaries viewed this mark making with a degree of confusion is, to Kelly’s eye, further evidence of the painter’s radicalism, anticipating Seurat (1859–91).

Auctions, the subject of chapter 5, offered yet another venue to show and sell one’s work, though arguably a riskier one. Rousseau had been a buyer at auctions for years as a collector of Japanese prints and of his friends’ works. He approached auctions of his own work with the same astute curation as he had navigated other aspects of the market, including strategically publicizing his sales, organizing pre-sale exhibitions, and ensuring a critical reception in the press. Kelly has transcribed the unpublished procès-verbaux of several of Rousseau’s sales in an appendix. While the listed titles are vague, the documents do allow for an accounting of both prices and purchasers, which notably included the state. Charles Blanc (1813–82), the Directeur des Beaux-Arts, bought ten paintings at Rousseau’s 1850 auction. The artworks were then distributed amongst ministerial offices, the Luxembourg Museum, and the Museum of Nantes (167). Blanc’s purchases are clear evidence that by the 1850s, Rousseau was an outsider in name alone.

The book’s final chapter considers how new reproductive technology allowed Rousseau to further disseminate his work. Rousseau collaborated with printers in his lifetime to create and sell reproductions of his paintings in both etching and lithography. The artist was also concerned with his enduring legacy and was especially interested in the potential of photographic reproduction to transmit his work across time and space. In his will, he requested that a selection of his work be photographed and reproduced in a published volume he referred to simply as Oeuvre (Work). Undertaken by Sensier and the critic Théophile Silvestre (1823–76), Choice of Painted and Drawn Compositions by Théodore Rousseau Reproduced by the Photographic Procedure of Adolphe Braun of Dornach (Bader: Mulhouse, 1869) features 120 photographs of Rousseau’s drawings, watercolors, and paintings. An introductory essay links the lesser-known drawings to the more publicly visible paintings, giving an impression of coherence to the artist’s oeuvre. The soaring prices of the artist’s posthumous market suggest his strategic self-positioning was a success.

The depth of research across Kelly’s book makes it an essential reference text for anyone working on the emergence of the art market in Paris. Kelly has highlighted numerous dealers, galleries, art spaces, and auctions that rarely figure in histories of the avant-garde.[2] He shows that practices we have come to see as emblematic of impressionism in fact began much earlier, and that the impressionists were working on a foundation of alliances between dealers, critics, auctioneers, patrons, and publics that had been formulated through the actions of Rousseau and his contemporaries. Many of these practices persist today, including solo shows and artist-organized auctions. It is this contemporary relevance that Kelly seeks to underscore in his use of the term “modern” in his title, though within the text itself Kelly refers to a “post-modern view of the artist as a savvy marketer” (7). Yet one of the things Kelly does most effectively is to deconstruct any pretense of a divide between artist and market, showing instead how thoroughly Rousseau’s technique developed in relation to his self-fashioning for specific publics.

Rousseau’s mythical identity as a modern, pioneering innovator was subtended by extensive, exceptional support. He had access to private means, formal training, all-male clubs, generous friends, the patronage of the elite, and exorbitant loans to cover his spending. Articulating the details of such support better contextualizes the limited numbers—and identities—of artists who eventually figure in our histories. As both Séverine Sofio and Paris Spies-Gans have recently shown, for example, there were far more women painting in nineteenth-century Paris than have been recognized.[3] Rousseau claimed to want to live and work “in complete freedom” (138). Yet freedom, as we well know, was only available to a select few. And even for Rousseau, it seems to have come at a price. In so meticulously tracing all of the ways in which Rousseau was intertwined with and indebted to a larger system, Kelly’s work helps us to continue to break down unilateral histories of modern art as a progression of independent agents and to study instead the structural conditions by which particular visions came to be celebrated. Rousseau’s prominence today has as much to do with the mechanisms he put in place to disseminate and publicize his work as it does with the work itself. Revealing the extent of those mechanisms offers a way of tracking how art history was made, and how it might be productively remade.

Notes

[1] Anne Wagner, “Courbet’s Landscapes and their Market,” Art History 4, no. 4 (December 1981): 411.

[2] For another effort to track the formation of the art market in Paris, including via auctions, see Lea Saint-Raymond, À la conquête du marché de l’art Le Pari(s) des enchères (1830–1939) (Paris: Classiques Garnier, 2021).

[3] Séverine Sofio, Artistes femmes. La parenthèse enchantée, XVIIe–XIXe siècles (Paris: Editions du CNRS, 2016); Paris Spies-Gans, A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in Britain and France, 1760–1830 (New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre and Yale University Press, 2022).