“Far too black”: Fanny Eaton, Simeon Solomon, and The Mother of Moses

by Roberto C. FerrariRoberto C. Ferrari is the curator of art properties at Columbia University Libraries, where he oversees the university’s permanent collection. He received his PhD in art history from the Graduate Center, City University of New York, focusing on nineteenth-century British art. Ferrari most recently curated the exhibition Time and Face: Daguerreotypes to Digital Prints (Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University, 2021–22). He has taught courses in art history and curatorial practice at Columbia, Drew University, and other institutions. He is the founder and comanager of the Simeon Solomon Research Archive. He has published extensively and given numerous presentations on the Jewish artists Rebecca and Simeon Solomon, the Black model Fanny Eaton, the neoclassical sculptor John Gibson, and the US-born painter Florine Stettheimer.

Email the author: rcf2123[at]columbia.edu

Citation: Roberto C. Ferrari, “‘Far too black’: Fanny Eaton, Simeon Solomon, and The Mother of Moses,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.1.2v2.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

The model chosen by the artist was far too black, and he has failed to eliminate that appearance.

- Athenaeum, May 12, 1860

At the 1860 annual exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts in London, the Jewish artist Simeon Solomon (1840–1905) exhibited an oil painting called Moses, now known as The Mother of Moses (fig. 1), depicting an infant in the arms of his mother with his sister looking on. Solomon painted this biblical picture in the Pre-Raphaelite style that favored naturalism over academic idealism. Although the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (including the artists William Holman Hunt [1827–1910], John Everett Millais [1829–96], and Dante Gabriel Rossetti [1828–82]) had disbanded by the mid-1850s, their work, with its intimate, naturalistic details and bright colors inspired by art made before the time of Raphael, continued to influence Solomon and other young artists.[1] Solomon presented to Victorian audiences a historical narrative painting inspired by the book of Exodus; a depiction of Orientalism; and a sentimental portrayal of a mother and her two children. As a nineteen-year-old Jewish artist making his mark with an Old Testament subject—shown to predominantly Protestant viewers at the Royal Academy—Solomon was drawing on the history of the Israelites and his own Judaic heritage. This included his family’s experience living through “Jewish Emancipation” in nineteenth-century England, when Jews were gradually granted more legal rights that allowed them to become integrated into British society and improve their socioeconomic status.[2]

The Mother of Moses would become Solomon’s first great artistic triumph, praised and derided by critics in nine reviews, a surprising number for a little-known artist.[3] A significant part of the painting’s success—and failure—was the depiction of Jochebed and Miriam, the mother and sister, respectively, of the infant Moses. The model for both of these figures was Fanny Eaton (1835–1924), a multiracial, working-class woman born in the British colony of Jamaica and the daughter of a formerly enslaved woman (fig. 2). Critics at the time were unaware of Eaton’s identity, but their visceral reactions to her skin color—“far too black,” according to the Athenaeum—reveal racist and anti-Semitic attitudes regarding their expectations for Solomon’s picture. They were particularly challenged by its naturalism, which contrasted with the idealized presentations of biblical figures normally seen at the Royal Academy. This article, then, considers at length the creation, display, and reception of this early painting in Solomon’s oeuvre, with a focus on the racial and sociopolitical implications of the painting’s subject, vis-à-vis its model, and the connections between Jewish and Black cultural identities at this time.[4]

Scholarly studies of the lives and careers of models across nineteenth-century art have increased in popularity since the 1990s, but this research has been challenging because models’ names were often omitted from public records, private accounts, and memoirs. Art historian Susan Waller has noted this common practice, especially in regard to Black models: “Performing for an audience of one, a model’s identity was eclipsed by that of the figure whom they impersonated on the model stand.”[5] While this practice was common in London’s academic world, there was a significant, radical difference for the Pre-Raphaelites and their followers. They selected models who were usually family and friends as well as people they found among the working classes in London, all of whom were typically unaccustomed to working as models. Rather than aspiring to idealism, the Pre-Raphaelites presented a new form of beauty via their models that was based on naturalism. This distinctive approach to the model has been reinforced by art historian Elizabeth Prettejohn, who has argued that the model is essential to understanding Pre-Raphaelite narratives and subjects: “Pre-Raphaelite images allow us to make either one of two imaginative leaps: we may jump from the image to the model . . . or from the image to the imagined character. . . . It is the simultaneous availability of both responses that distinguishes the Pre-Raphaelite artistic project.”[6] Art historian Jan Marsh has also argued in regard to female models among the Pre-Raphaelites that the models could have opportunities for agency, “taking part in the creative process.”[7] This means that many of the models did not just pose for the artists but portrayed characters and, according to Marsh, were “‘cast’ in a specific role,” a proposition that argues for their more “active participation in the picture-making process.”[8]

Because of this intimate approach to the model and the figures they represented, Eaton should be seen as an essential part of any interpretation of Solomon’s painting, particularly because of her multiracial background and the reaction of critics to her skin color. Eaton’s “Blackness”—adopting the term utilized and theorized by art historians Adrienne L. Childs and Susan H. Libby for depictions of people of color in nineteenth-century art—meant that the model’s skin color, as seen in life and depicted in the painting, suggested to viewers her innate connection to “the realities of slavery and servitude.”[9] Childs and Libby argue further that “the notion that any amount of black blood, of African-ness, introduces essential qualities of blackness to the individual and impacts the way she or he is perceived and represented.”[10] Solomon may have chosen Eaton as his model because, as a working-class woman of color and a mother, she conveyed for him the naturalistic appearance and social status he wished to portray in his representations of Moses’s mother and sister. But Eaton’s Blackness also would have reinforced the biblical narrative of the Israelites enslaved in Egypt and, by association, would have drawn attention to contemporaneous interest in abolition for enslaved Black people around 1860. This multilayered interpretation suggests, then, that Eaton’s presence in this painting by a Jewish artist is more complex than the binary approach of Childs and Libby, who have contended that “blackness could only be perceived by whites in opposition to notions of whiteness that placed whites as agents (economic, political, legal, intellectual, cultural) and blacks as objects of agency.”[11]

Reviewers saw The Mother of Moses at the time as either a tour de force or a failure. While a critic for the Athenaeum believed the painting championed Solomon’s talents in a way that would make him “a man of mark” and “presage his future success,” another writing for the Saturday Review derided the painting as “a singular freak of fancy” and “the ugliest picture in the room.”[12] Nearly all the critics who panned Solomon’s painting did so because it did not meet their expectations of what the subject should represent: an idealized (i.e., whiter) biblical representation of Moses and his family. This criticism, discussed below, is blatantly racist and anti-Semitic. Indeed, the same Athenaeum critic who praised Solomon’s artistry also complained (see my epigraph) that the faces of Moses’s mother and sister were “far too black” and went on to assert that Solomon had failed to “eliminate” his model’s skin color.[13]

Considering both Eaton’s life and this criticism of The Mother of Moses, it is surprising to discover that neither the painting nor the model herself, to date, have ever been included in the historiography of Black people in nineteenth-century art.[14] Numerous individual works of art contemporaneous with Solomon’s painting that feature images of Blacks have received scholarly attention. These include sculptures such as Charles-Henri-Joseph Cordier’s (1827–1905) Bust of a Woman (African Venus) (1851; Art Institute of Chicago); John Bell’s (1811–95) A Daughter of Eve (The American Slave), exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1853 (National Trust, Cragside, Northumberland), and his The Octoroon, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1868 (Blackburn Museum & Art Gallery, Blackburn); and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s (1827–75) Why Born Enslaved! (fig. 3); and paintings such as Richard Ansdell’s (1815–85) Hunted Slaves (National Museums Liverpool) and Eyre Crowe’s (1824–1910) Slaves Waiting for Sale, Richmond, Virginia (fig. 4), both exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1861; and Edouard Manet’s (1832–83) Olympia (1863; Musée d’Orsay, Paris), picturing the model Laure.[15] This long-overdue art historical scholarship is beginning to restore the names of, and convey the challenges of life for, heretofore forgotten Black, Indigenous, and other people of color in the nineteenth century, leading to an acknowledgment of these individuals not as marginalized others but as significant individuals whose lives and circumstances are essential to a transatlantic-based history of nineteenth-century art. This scholarship, in which Solomon’s painting must be included, also foregrounds the socioeconomic, cultural, and political structures and ramifications of slavery, abolition, and emancipation.

Art historian Sarah Thomas has shown how, after the establishment of the Royal Academy in 1768, antislavery paintings occasionally made appearances at the annual exhibitions to encourage abolition. The British government ended the slave trade in 1807 and slavery itself in 1834. With a renewed sense of nationalistic pride, the Royal Academy exhibition of 1840, according to Thomas, was where “the abject horror of slavery took centre stage” with the display of Joseph Mallord William Turner’s (1775–1851) Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On) (1840; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) and François-Auguste Biard’s (ca. 1798–1882) The Slave Trade (ca. 1883; Wilberforce House, Hull City Museums and Art Galleries), history paintings that suggested Britain’s history of slavery was in the past and “coincided with an invigorated anti-slavery movement whose attentions were turning to the international slave trade.”[16] The one significant area of the world toward which the British fight for abolition was strongly directed was the United States, an effort that climaxed in the 1850s, due, in part, to the immense popularity in England of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Paintings related to the book were also exhibited at the Royal Academy, and many theatrical iterations sprang up throughout London. According to literature scholar Sarah Meer, for better or for worse, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, “by virtue of its ubiquity in Britain . . . came to be seen as the primary available authority on American slavery.”[17] Despite the mixed messages readers perceive today in the novel’s depictions of enslaved people and enslavers, at the time the book exemplified what art and literature historian Marcus Wood has called the “visually bizarre, ethically inconsistent and morally disastrous” abolitionist material culture that was popular in the 1850s.[18] Complicating matters for the British, however, was the country’s economically important textile industry, a global enterprise dependent on imported cotton that tacitly supported international slave labor, most notably in the southern United States. Art historian Anna Arabindan-Kesson has argued: “As a country that decried slavery, Britain nevertheless allowed slave-grown cotton to sustain a significant part of its domestic industry,” that is, textiles produced in northern England and exported worldwide.[19]

I cite this history not to suggest that The Mother of Moses is an outright abolitionist painting or even to claim that Solomon himself was an abolitionist, as there is little biographical evidence to support this. Rather, painted and displayed in 1860, Solomon’s painting should be recognized as one among other important contemporaneous works of art that drew attention to people of color as central to the picture’s narrative and thus reflected the cultural and social politics of slavery at that time. Similar to the “the black presence” in Rossetti’s painting The Beloved (fig. 5)—for which Eaton was the model for a background figure and which has been interpreted by Marsh as related to slavery “politically as well as pictorially”—Solomon’s presentation of Eaton as the enslaved mother and sister of Moses is essential to any interpretation of the painting’s narrative.[20] Similarly, for Marsh, Hunt’s painting The Afterglow in Egypt (1854–63; Southampton City Art Gallery), with its visual and biblical references to Egypt “as a land of slavery,” was a reminder that “British artists were being urged to declare themselves as supporters or opponents of emancipation.”[21] Linked to these ideas of Egypt and slavery was Moses, savior of an enslaved people.[22]

Symbolic references aside, then, Solomon’s painting is about the Israelites enslaved in ancient Egypt, a narrative that deserves reconsideration not just because of its connection to artistic interest in Black bodies and slavery in works of art around 1860 but also because of the changes in the status of Jews living and working in mainstream London, a topic that would be of concerted interest to a Jewish painter at the time. As will be explored below, the immigrant Jewish population in England historically had had few opportunities for advancement, despite some families having lived in the country for multiple generations. Even after 1830, as Jewish Emancipation in England took hold, some Jews in mid-Victorian London remained marginalized in many areas of society and were often subject to discrimination, no matter how much they had acculturated. Solomon’s entrée into this world was due to the changing status of his Jewish family’s socioeconomic background, as more opportunities were made available for them to prosper. His art, in turn, largely focused on representations of Israelite figures and narratives from the Hebrew Bible (i.e., the Torah and the Prophets, or the Old Testament) as well as depictions of Jewish religious and cultural traditions (figs. 6, 7), drawing on the past but creating innovative subjects for a new audience.

These Hebraic subjects, then, were welcomed, even expected, from Solomon, by Jews and Gentiles alike because he was Jewish, and it was tacitly assumed that he was an expert on his people, unchanged from the past. For example, his friend and fellow artist William Blake Richmond (1842–1921) called Solomon “a fair little Hebrew, a Jew of the Jews,” and noted of his work that “no one but a Jew could have conceived or expressed the depth of national feeling which lay under the strange, remote forms of the archaic people whom he depicted and whose passions he told with a genius entirely unique.”[23] Art historian David Bindman has called this belief in an uninterrupted, contiguous visual history of racial and ethnic types, from antiquity to the present, a “representational fallacy,” and has noted extensively how it reinforced racist actions and practices in the nineteenth century.[24] Curiously, Solomon himself may have even believed this fallacy, or at the very least he may have had a sense of the expectation of what his Jewishness as an artist would mean for Gentiles and how he should depict the Israelites in his art.

Some scholars have continued to argue for this innate Jewishness as an important part of why Solomon was so popular then and now, inadvertently blurring these lines of race and ethnicity over time. For instance, art historian Norman Kleeblatt has pointed to the artist’s “dark, ethnic types, along with the appearance of exotically appropriate costumes, architecture, and other trappings” as having been perceived by his contemporaries “as a reflection of Solomon’s intimate connection to and understanding of his religio-cultural heritage.”[25] Art historian Gayle Seymour has argued that The Mother of Moses may have had personal meaning for Solomon, as the painting links “Moses to his family despite the eventual adoption [by the Egyptian daughter of the pharaoh], and therefore to his racial and religious roots—an allusion that must have been of particular importance to Solomon, himself a Jew living among gentiles.”[26] Seymour has also demonstrated that the artist’s early Hebraic subjects, painted and exhibited primarily for non-Jewish audiences, “addressed the paradox of Jewish emancipation—the fact that Jewish-Gentile interaction both fostered Jewish survival and undermined it.”[27] And art historian Susan Tumarkin Goodman has argued that Solomon’s Jewishness inevitably led to his interest in these religious narrative subjects, his background even guiding him later toward Christian subjects and demonstrating his more wide-ranging awareness of “social and political change throughout nineteenth-century Europe.”[28] She also contends that Solomon and his European Jewish contemporaries, operating through emancipation and acculturation, “were remarkably well placed to serve as intermediaries, by transmitting aspects of Jewish life and tradition as well as secular experience, in ways that non-Jews would comprehend.”[29]

The Mother of Moses was Solomon’s first critical success. After its exhibition, the painting was purchased by the important Pre-Raphaelite collector Thomas E. Plint, a stockbroker based in Leeds, who went on to purchase two more paintings and three drawings by Solomon, becoming his first major patron.[30] The painting was also awarded a silver medal in the category of history painting by the Society for the Encouragement of the Fine Arts, who noted of its merits: “the originality of the subject and treatment, the impressiveness with which it is rendered, as well as by the artistic skill displayed in its execution being such as to hold out high promise for the young artist who produced it, and who is only 18 [sic] years of age.”[31] Its success inspired Solomon to paint a sequel two years later, The Finding of Moses (fig. 8), in which mother and daughter celebrate the return of Moses to them by the pharaoh’s daughter so Jochebed can nurse him.[32] And the Dalziel brothers commissioned Solomon to transform The Mother of Moses into the first of twenty biblical subjects in wood engravings that later appeared in Dalziels’ Bible Gallery and Art Pictures from the Old Testament (fig. 9).[33] Building on this background, this article considers the intersections of Jewish and Black identities in mid-Victorian history as well as the subjects of slavery and emancipation in The Mother of Moses, the artist’s first success at the Royal Academy. Through its depiction and inclusion of the Black model Eaton, Solomon’s painting should be seen anew as a major contribution to the history of nineteenth-century art.

The Painting

The Mother of Moses does not directly illustrate a story from the Old Testament (the Torah) but rather is inspired by it and presents a naturalistic, humanizing scene for a contemporary audience. According to the book of Exodus, the population of the Israelites, who had been enslaved in Egypt, had grown so large that the pharaoh ordered the execution of their newborn sons:

And there went a man of the house of Levi, and took to wife a daughter of Levi. And the woman conceived, and bare a son: and when she saw him that he was a goodly child, she hid him three months. And when she could not longer hide him, she took for him an ark of bulrushes, and daubed it with slime and with pitch, and put the child therein; and she laid it in the flags by the river’s brink.[34]

Solomon’s painting pictures the moment before Jochebed is about to be separated from her son. Miriam, who holds the cradle in which Jochebed will place the infant, reaches up to see him nestled in their mother’s arms. This palpable moment is about sacrifice, a demonstration of Jochebed’s faith in God that her son will be protected and that she needed to part with him in order to save him. Victorian audiences also would have known what happened next. Miriam would be watching from a distance and would see the child discovered by the pharaoh’s daughter. She would volunteer to find a wet nurse—Jochebed herself—after which the child would be raised by the pharaoh’s daughter as her own and named by her.[35] Moses would later witness the atrocities against the Israelites, kill a slave overseer, and eventually become the leader who forces the pharaoh to free the Israelites after God sends a series of plagues.

It may seem unusual that Solomon did not paint a heroic representation of Moses as an adult leader. Nor did he paint the more common image of the discovery of Moses by the pharaoh’s daughter. In one of Solomon’s early sketchbooks from the mid-1850s, an extant drawing in pen and ink over graphite shows the girl with long, dark hair playfully holding and kissing the newly-discovered infant Moses, who responds to her embrace (fig. 10). But rather than paint this subject, he focused on Jochebed and Miriam with the infant Moses in a domestic interior, highlighting maternal devotion and thus Jochebed’s importance in this biblical narrative. Theologians Carmen Yebra-Rovira and David J. Zucker have noted that in the mid-nineteenth century there was an increase in the number of books, written in various European languages, that celebrated the important role of women in the Bible.[36] Yebra-Rovira sees these texts as championing the “feminine story” in the nineteenth century, emphasizing religious women’s roles as caretakers and thus models of excellence and “composed for the edification of women or young people or for the formation of the clergymen in charge of the formation and/or accompaniment of women.”[37] One such book, The Women of Israel, was written by Grace Aguilar, a Sephardic Jewish woman who lived in England. Her book was so popular that it went through numerous editions and reprints, including in 1858, less than two years before Solomon painted The Mother of Moses. Her evocative visualization of the moment in which Jochebed is about to part from her infant seems to share similarities with Solomon’s painting:

We may picture, with perfect truth and justice, her last lingering kiss pressed upon the lips, cheek, and brow of the unconscious babe; her waiting till sleep closed those beauteous eyes, which, in their pleading gaze, seemed to her fond heart beseeching her not so cruelly to abandon him.[38]

Solomon’s depiction of Jochebed, Miriam, and Moses as an infant, then, may not be unique in the history of art, but it certainly was among the first to provide Victorian audiences with a more naturalistic representation of this biblical family. Viewers would have understood that this story recounted an act of bravery on Jochebed’s part. Thus, the painting becomes a profound statement, a biblical-themed exemplum virtutis (lesson in virtue) if not a morality picture, about maternal love and sacrifice for a greater good.[39] But Solomon does not idealize his figures or the setting; rather, he combines a historical genre scene with Orientalist traits, conveying an evocative scene in Egypt as an exotic time and place in the past but with relevance to contemporary audiences. These traits are evident in details such as the family’s humble hut; the cradle of woven bulrushes in Miriam’s arm; the ancient harp on the wall; the linear bands of bright color on the otherwise poor, woolen garments the women wear; and, most notably, the pyramid outside the window (fig. 11). The Mother of Moses is also significant for its emphasis on contours and distinctive edges of color as well as its rich use of symbols, all of which recall Pre-Raphaelite paintings in the quattrocento style. For instance, the thriving plant on a table at the left suggests Jochebed’s nurturing qualities as a mother, reinforced by the position of the infant at her breast as if he is suckling, a reminder of how Moses will grow from these humble beginnings to become a powerful leader, thanks to his mother. There are also two birds resting on the windowsill, on the precipice between the confined space of the interior and the freedom of the world outside. They are likely mourning doves, symbolizing peace, hope, and love, but one of them is trapped visually behind the strings of the harp, reminding viewers of the enslavement of Moses’s family.[40]

Art historian Michaela Giebelhausen has argued that the 1850s saw an important transition in the creation and display of religious-themed paintings in British art because of the Pre-Raphaelites. For Victorian viewers, who were predominantly Protestant, religious “pictorial traditions held no sway and belief centred exclusively on the biblical text,” leaving painters with “the complex task of translating the Bible for the age.”[41] Giebelhausen argues that this decade of change began with visceral criticism waged against the naturalism in Millais’s Christ in the House of His Parents (The Carpenter’s Shop) (1849–50; Tate Britain, London) but ended with high praise for Hunt’s attention to historical details in his painting The Finding of the Savior in the Temple (fig. 12), which was painted in 1854–55 but first exhibited in 1860 at Ernest Gambart’s German Gallery, near the Royal Academy where Solomon’s painting was on view.[42] Both Millais’s and Hunt’s paintings relate to scenes from the life of Christ, whereas the subject of Solomon’s painting is from Exodus. But for Protestant Victorian audiences, Solomon’s subject could have alluded to depictions of the Madonna and Child with Saint John or even lamentation scenes of the Madonna and the dead Christ with Mary Magdalene, Christian religious paintings that had a more established visual history.[43]

Seymour has suggested that Solomon’s figures may have been inspired by the standing mother and child seen in the far background of Hunt’s Finding of the Savior in the Temple, while Prettejohn has noted that Solomon’s painting shares much with Hunt’s work “in its attention to historically accurate details” and the artist’s efforts toward “ethnic or racial accuracy in the representation of his figures,” suggesting a “different kind of truth . . . the faithful depiction of his own religious community.”[44] Hunt’s efforts at historical accuracy, however, are more grandiose than Solomon’s. A different painting by Millais, The Return of the Dove to the Ark of 1851 (fig. 13), may, in fact, share elements with The Mother of Moses. In Millais’s painting the girls stand inside Noah’s ark, huddled closely and holding in their arms the dove. This simpler, triangular arrangement of figures recalls the compositional structure of Jochebed, Miriam, and Moses; the birds (doves) in both works have a similar symbolic meaning; and both works are rare examples of narratives from the Old Testament by Pre-Raphaelite artists. Ultimately, neither Millais’s nor Hunt’s painting was a direct influence on Solomon’s work, but seen in this context one can include The Mother of Moses in the spectrum of important British religious paintings at the time that emphasized naturalism and historical accuracy. What made Solomon’s painting unique was his approach to the subject as a Jewish artist and his choice of model, a multiracial woman of color, to represent two Israelite women.

The Artist

During the late nineteenth century and through most of the twentieth century, Solomon rarely appeared in surveys of Pre-Raphaelitism, and when he did there was a consistent emphasis on his tragic decline as an artist. In his lifetime, he was even rebuked by some former friends, such as the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, who referred to Solomon as “a thing unmentionable alike by men or women, as equally abhorrent to either—nay, to the very beasts.”[45] Solomon was branded this way after his arrests in 1873 in London and the following year in Paris for homosexual crimes, serving prison sentences for a few weeks in the first instance and six months in the second. He thereafter lived on the streets and in workhouses, and suffered from addiction.[46] Despite this so-called fall from grace, he produced hundreds of works of art and garnered a new group of supporters and patrons, and after his death in 1905 his work was shown again in London exhibitions.[47] While many scholars today have explored the queer content of Solomon’s art, I am focusing in this article on The Mother of Moses and the model Fanny Eaton, and considering instead the intersections of Jewish and Black cultural identities with regard to this painting.[48]

The story of Moses from the Torah was well known to Solomon from the time of his own childhood. Born in the East End of London in 1840, Solomon was the youngest child in a mercantile family of Ashkenazi Jewish descent that had emigrated from the Netherlands or Germanic states during the eighteenth century. Following the expulsion of Jews from England in 1290 by King Edward I, it was only during the Republic and Restoration periods of the seventeenth century that Jews were permitted to return to help invigorate a global economy. By 1851 there were approximately twenty-five thousand Jews in London, which was less than 1 percent of the entire urban population of 2.6 million; most were Ashkenazi and two-thirds were considered lower working class and impoverished.[49] Jews could not attend Oxford University or the University of Cambridge; nor could they serve in politics (along with Catholics and dissenters from the Church of England), because all students and politicians were expected to pledge an oath to the church. In 1829, Parliament passed the Catholic Emancipation Act, which, though it focused on Irish Catholics and their ability to enter Parliament, was the beginning of a series of reforms that also gradually impacted the legal status of Jews as British citizens.[50]

Art historian Monica Bohm-Duchen has suggested that the Solomon family was very conservative in their religious and cultural practices.[51] Most Jews in Victorian England were in fact Orthodox, but as historians Steven Singer and Todd Endelman have shown, Victorian Orthodoxy was not characterized by the same level of strictness associated with Orthodox Judaism today.[52] This was largely because of assimilation and acculturation: middle-class Jews in Britain presumably wanted to be part of society and not seen as foreigners. As Endelman has further noted, “by the end of the century, the Jewish community in England had become overwhelmingly English in manners, speech, dress, deportment, and habits of thought and taste.”[53] The Solomons exemplify, then, this assimilation and acculturation in the early-to-mid-Victorian period. For instance, Solomon’s father and all of the artist’s brothers are documented as having been circumcised, and the family belonged to the New Synagogue, established in the late 1700s by mercantile immigrant Ashkenazi Jews, but acculturation also meant that they most likely did not attend synagogue on a regular basis because of their commercial and artistic interactions with non-Jewish communities.[54] The Solomons celebrated Jewish holidays such as Passover, but Solomon’s friend and fellow artist Henry Holiday (1839–1927) noted in his memoirs that Solomon “did not observe the Jewish restrictions” regarding food.[55]

The greatest impact on the lives of Jews seeking to advance in society at this time was commerce. This advancement included Michael Solomon, Simeon’s father, who in June 1831 became one of the first men of the “Jewish Nation” to be granted the Freedom of the City of London.[56] This inclusion allowed Jewish merchants to legally expand their businesses—for the Solomons, this was the sale of Leghorn hats and embossed paper goods like doilies and stationery—and thus improve their socioeconomic status. The change in social status thus enabled Simeon and his older siblings Abraham (1823–62) and Rebecca (1832–86) to study and pursue careers in art, a choice likely encouraged by their mother, Kate Levy Solomon, who was reportedly an amateur painter of miniatures. Abraham and Rebecca became successful painters and were early influences on Simeon’s artistry, the trio even sharing a studio for a time at 18 Gower Street, Bedford Square, a few blocks from the British Museum.[57] Simeon was admitted to the Royal Academy schools in April 1856, following Abraham’s art education at this institution. However, Simeon only studied there for a few years, choosing instead the example of Rossetti who a decade earlier had abandoned the Royal Academy to form the countercultural Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Indeed, upon seeing Simeon’s early sketchbooks from his teenage years, the artist George Price Boyce recorded in his journal on two separate occasions: “Saw some remarkable designs by [Abraham Solomon’s] young brother (Simeon) showing much Rossetti-like feeling”; and “Much interested with a book of sketches by young Simeon.”[58] By connecting Simeon’s early designs with Rossetti’s art, with its medievalist effects and attention to detail, he was noting the youth’s future as part of the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

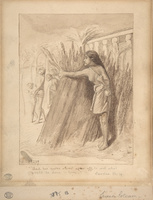

As mentioned above, one of the surviving drawings from these early sketchbooks is a depiction of the daughter of the pharaoh playing with the infant Moses (see fig. 10). This is not a subject Solomon chose to paint, but it does suggest his early interest in Moses, which manifested itself in at least two other extant drawings made a few years later. In the first, signed with his monogram and dated February 22, 1859, Miriam is shown hiding in the bulrushes, spying on the pharaoh’s daughter and her entourage in the distance as they are about to discover the infant on the Nile bank (fig. 14). Drawn in ink with added brown wash over graphite, this depiction shows Miriam in profile, a compositional arrangement that Solomon did retain in his painting.[59] Another drawing, in pencil and wash, also utilizes this profile view for Miriam, but it is more important as a working study for the final composition (fig. 15).[60] As in the painting, Solomon brings mother and daughter together, with Miriam holding the cradle and Jochebed embracing the infant. But in this drawing the family is outdoors, about to put the baby into the cradle and set it afloat on the Nile. This placement gives the narrative more clarity than in the painting and thus follows more closely the biblical text. The indoor scene shown in the painting, by contrast, reinforces the domestic nature and emotional connection among the figures. The drawing also has two inscriptions: the text at center top reads “shoulder lower”; the other, near Miriam’s arm, reads “straighter with should[er],” with the last two letters cut off. The handwriting closely resembles Solomon’s own and suggests that he was thinking about how to refine the anatomies of the figures, perhaps at the advice of an instructor or colleague. One additional noteworthy detail in this drawing is the way Solomon has rendered the skin tone of the figures with hatch marks and wash. This suggests Solomon’s interest in depicting Jochebed and Miriam as people of color.

In addition to these drawings, two of four head studies Solomon made of Eaton were utilized for the main figures in the painting and will be discussed below. Considering Solomon’s interest in head studies and portraits at this time, it is worth concluding this section with a brief look at his self-portrait made five months before the studies of Eaton.[61] Drawn on June 1, 1859, at the age of eighteen, Solomon’s self-portrait (fig. 16) is a close-up image of a dreamy-eyed youth with wavy hair, positioned before a stained-glass window possibly depicting King Solomon, which links the artist to the Pre-Raphaelites’ interest in medievalism as well as referencing his Judaic cultural past and his namesake. A tassel hanging before the window could be attached to an unseen shade or may suggest the tzitzit, the woven strings attached to the religious tallit worn by Jewish men to remind them of their connection to God.[62] The tassel’s elongated shape and form may also have phallic connotations, further evidence of Solomon’s self-awareness as a Jew. The phallus as a personal symbol represents what historian Sander L. Gilman has called the sign of the “damaged male body”: the circumcised penis, one of the primary markers of difference for Jewish men and masculine identity among Gentiles in nineteenth-century society.[63] As a Jewish youth coming to terms with his homosexuality and queer identity, the physical, psychological, and emotional significance of Solomon’s circumcision might have been strong, reinforcing feelings of marginalization he may have experienced among his homosocial (and uncircumcised) circle of male artist friends. Powerfully rendered, this self-portrait drawing is a testament to Solomon’s draftsmanship and artistic skill, and suggests the intimate approach to the model that he would take when he drew Eaton just a few months later.

The Model

Fanny Eaton (see fig. 2) was born a freewoman of color in Jamaica on June 23, 1835.[64] She was christened Fanny Antwistle, the daughter of a woman named Matilda who was born enslaved to a family of enslavers whose surname was alternatively documented as Foster and Forster. In the early nineteenth century, Jamaica was among the most financially lucrative of the British colonies, having transitioned from livestock to sugar as a major export by the late 1700s, which reinforced the need for plantations with large enslaved workforces.[65] Jamaica was also the site of the Baptist War, one of the largest rebellions of enslaved people in the Caribbean, which took place over eleven days from 1831 to 1832 and undoubtedly was one contributing factor in the British abolition of slavery. As noted earlier, although the British government had banned the slave trade in 1807 and slavery itself in 1834, scholars have shown that Britain tacitly supported a global economy of enslaved people through its support of the transatlantic cotton industry, which led to tremendous financial success for many during the Victorian period.[66]

This genealogy and history have relevance to the life of Eaton, not just because she was a woman of color born in Jamaica but because she was employed later as a model for the Pre-Raphaelites, appearing in their paintings as various typecast characters because of her skin color and physiognomy.[67] Solomon is credited with having produced the earliest dated images of Eaton. It is uncertain how the two met, but the United Kingdom’s census of 1861 suggests they lived relatively close to each other in London. Solomon resided with his family at 18 John Street in Holborn, about one mile southeast of where Eaton resided with her family at 4 Brunswick Street (now Tonbridge Street) in St. Pancras. Eaton was employed regularly as a charwoman and likely worked in numerous houses, although not that belonging to the Solomons, who had live-in servants at the time. It is possible the two met in the streets of London, where the Pre-Raphaelites often discovered their models. Solomon likely noticed Eaton’s distinctive, striking features, then captured them on paper and canvas.[68]

But Solomon was certainly not the only artist who wanted to draw or paint Eaton, as she became a popular model during the first half of the 1860s. There is a possibility that Solomon’s head studies were made during a series of sessions with the sketching club that he formed with friends from the Royal Academy school, including Holiday, Albert Joseph Moore (1841–93), Richmond, and Marcus C. Stone (1840–1921).[69] This club allowed the men the opportunity to embrace the spirit of Pre-Raphaelitism in their drawings and paintings, which were intentionally different from the rote copy work taught at the Royal Academy. Thereafter, Eaton’s face appears in works by many artists associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, including Ford Madox Brown (1821–93), Millais, Frederick Sandys (1829–1904), Rebecca Solomon (fig. 17), Joanna Boyce Wells (1831–61) (fig. 18), and others. Rossetti had employed Eaton as a model (fig. 19), and, as noted above, incorporated her as a figure in the background of The Beloved (see fig. 5). In a letter of 1865 to Brown, Rossetti corrected Brown’s misunderstanding about Eaton’s multiracial identity: “She isn’t Hindoo however but mulatto.”[70]

Brown’s conflation of South Asia with the West Indies is problematic unto itself, but more relevant to this article is Rossetti’s use of the racist term “mulatto,” common at that time and long afterward, to describe Eaton and her contemporaries’ multiracialism. According to historian Steeve O. Buckridge, Jamaican society during Matilda’s and Fanny’s lifetimes was divided into three castes: Africans who were enslaved; multiracial people of color, the children of white people and enslaved people or freed people from Africa, conceived either through rape or consensual relationships, known generally across the Caribbean as Creoles; and white plantation owners, workers, and enslavers of predominantly English, Irish, and Scottish nationality.[71] In this caste structure, then, Fanny and Matilda were Creole. In a slave registry of 1826 Matilda is in fact documented as Creole, born in 1818 to an enslaved woman named Bathsheba and the property of John Forster, Esq.[72] In the context of genealogy, then, it is worth noting that the nearly absent name of Antwistle in extant archival records of Jamaica suggests that the only likely identity for Fanny’s biological father may be a twenty-year-old British soldier named James Entwistle, who died and was buried in St. Catherine’s parish eleven days after Fanny’s birth. Matilda’s decision to give her daughter a version of the father’s surname thus emphasized that Fanny was born free and had a white British father.

The abolition of slavery throughout the British empire was followed by four years of enforced apprenticeship, during which time formerly enslaved people such as Matilda presumably continued working for their previous enslavers. In the 1840s, Fanny and Matilda traveled to London. They appear in the United Kingdom’s census of 1851, with Matilda declaring herself married under the name Entwistle. Around 1857, Fanny seems to have entered into a common-law relationship with James Eaton, as no record of their marriage exists. His family worked as porters and horse cab proprietors. Fanny and James had at least ten children who survived to adulthood. When Eaton began modeling for Solomon in November 1859, she already had one child (Fanny Matilda Eaton) and was pregnant with her second (James Eaton), born in early 1860, at the time Solomon was painting The Mother of Moses. The infant Moses pictured in the painting may in fact be Eaton’s newborn son, whom she would have been nursing at the time. That Moses appears in the painting cradled in Jochebed’s arms, near her nourishing breast, reinforces the double nature of Eaton as model and mother, intrinsically embedded into the painting’s biblical narrative and subject.[73]

When considered among other subjects with themes of slavery in visual culture and art at the time, this maternal image is significant. Depictions of enslaved mothers and children reinforced calls for emancipation because of the constant threat that this maternal bond would be torn apart. This can be seen, for instance, with the figures at the center of Crowe’s contemporaneous painting Slaves Waiting for Sale, Richmond, Virginia (see fig. 4). One of the primary storylines in Uncle Tom’s Cabin relates to the enslaved woman Eliza, whose son is going to be taken away from her and sold; as a result, she flees with him so they will not be separated, eventually making their way to freedom. Jochebed’s desperation to hide her child so he is not killed, and then her choice to part with him in order to save him, is part of this tragic legacy of slavery and motherhood.[74]

Consider another contemporaneous example of a painting depicting an enslaved mother with children, for which Eaton was also the model: The Slave, ca. 1865 (fig. 20), by Richmond, Solomon’s friend and one of the members of their sketching club. In the painting, a mother clutches an infant in her arms, holding it near her breast, while her second child, naked, clings desperately to her leg. It is possible, but uncertain, that Richmond’s painting also depicts Jochebed, Miriam, and Moses, but here viewers witness their anguish, pain, and desperation, strongly reinforcing the atrocity of slavery and its brutal reality in association with motherhood.[75] This is a stark contrast to the more subtle, yet still heartbreaking, sentimental scene of the enslaved mother and her children in Solomon’s painting.

In late 1859, Solomon made a series of intricate head studies of Eaton. Three of the studies are signed and dated November 7, 8, and 11, 1859, respectively, making them the earliest-documented record of Eaton having posed for the Pre-Raphaelites. Solomon utilized two of them for The Mother of Moses. In the first (fig. 21), Eaton is shown looking down with her head turned slightly to her right. Solomon paid close attention to her facial structure and applied light-colored hatching to suggest a complexion darker than the color of the paper, emphasizing this further on her proper left side, which is seen in shadow.[76] The second drawing, made the following day, is a profile of Eaton (fig. 22). Here Solomon spent less time on her features and more on distinguishing her from the background. What both drawings convey with skill are the waves and loose tendrils of hair that Solomon saw when looking at Eaton. The third drawing (fig. 23), dated November 11, is also a head study which Solomon may have used for other paintings a few years later.[77] In this drawing, he captured Eaton’s head turned slightly to her left. By either erasing the graphite in the depiction of her eyes or adding white highlights to them, he suggested a reflection of light that gives the portrait vitality, a sign of his artistic skill also seen in his own self-portrait five months earlier. Solomon’s attention to detail and the close-up views of Eaton’s face in all three of these drawings exemplify the “intimate and personal” approach to figurative subject matter that art historian Colin Cruise has described in Pre-Raphaelite drawings, which opposed academic norms and “helped challenge accepted rules of representation and encouraged individuality and variety.”[78] Solomon’s extant studies of heads and portrait drawings from this time exemplify this practice: they dominate each sheet, making them seem larger-than-life while simultaneously capturing a remarkable level of intimacy.

This approach is seen further in the drawing of Eaton that Solomon made eleven months later, on October 2, 1860 (see fig. 2). While it too may have been intended as a study for later paintings, this drawing appears to be more a finished portrait and less a study, as seen in the drawings of 1859. Inscribed on the bottom, in another hand, is an early effort to identify the sitter: “Port of Rebecca Solomon.” To date, no known photographs of Solomon’s sister have been found, and it is unclear if any of the other women one sees in his paintings and drawings are representations of Rebecca, so this question of identity is not surprising. But one can see clearly that the figure represented is Eaton. Related to this is a similarly mistaken identification of the sitter for the Fitzwilliam Museum drawings, who until recently had been identified as “Mrs. Fanny Cohen,” a misreading of the inscription on the bottom of the third head study from November 11.[79]

Speculation about the identities of sitters in portraits and figurative works is common and attributions may change over time. But it is concerning that these studies of Eaton, a multiracial woman of color from Jamaica, were assumed by viewers and scholars, even in recent years, to be depictions of Jewish women (Rebecca Solomon and a certain Fanny Cohen). This misidentification suggests assumptions about physiognomy and otherness that continued to persist long after the Victorian period, when phrenology and ethnographic taxonomy were popular. As noted earlier, Eaton’s identity has been documented for decades, but assumptions about Solomon’s “Jewish” models suggest ongoing (likely unconscious) racial and anti-Semitic biases, reminding us of Bindman’s “representational fallacy,” that is, the idea that an artist who was a Jew could only have used Jewish models for his Hebraic subjects.[80] In fact, what is remarkable is that the Solomon-Eaton collaboration suggests interactions between two marginalized groups in mid-Victorian London that have rarely, if ever, been researched.[81] Nevertheless, ongoing prejudices have prevailed. Eaton’s great-grandson, Brian Eaton, has noted in his research that until recently Fanny had been “erased” from Pre-Raphaelite history and was someone her own descendants were “able to ‘forget,’” referring to her as Native American or Portuguese but never Black or a woman of color from Jamaica, let alone the daughter of a formerly enslaved woman.[82]

In each of Solomon’s head studies, Eaton’s hair is a focal point. Contemporaneous images of Black women with their hair uncovered are more frequently found in French art; artists such as Carpeaux (see fig. 3) and Cordier deployed hair to both exoticize and sexualize their figures. Art historian James Smalls has astutely dubbed depictions of this sort the “dressing up” and “stripping down” of Black women in Western art, concepts laden with colonialism and misogyny.[83] In Pre-Raphaelite art, hair is a well-known trope, operating as a symbol of beauty, rebelliousness, power, and seduction, especially among Rossettian “stunners.”[84] In this context, it is perhaps less surprising that Eaton’s hair is revealed, but this exoticization of Eaton as a woman of color makes it necessary to consider more closely how her hair is presented in Solomon’s drawings and the final painting. He drew attention to Eaton’s ethnic and racial origins in his head studies, but he imbued them with intimacy and attention to detail. They do not “dress up” or “strip down” Eaton, as Smalls suggests. Yet, the use of the drawings as preparatory studies meant that Solomon did “dress up” Eaton in another sense, to suit his biblical narrative in the painting The Mother of Moses.

Indeed, Pre-Raphaelite attention to historical accuracy meant it was necessary to represent Jochebed, as a married woman, wearing a headscarf, while Miriam, who was young and unwed, could appear with her hair uncovered. In traditional Jewish law, married women are prohibited from exposing their hair because it is an ervah, or erotic stimulant, reserved for their husbands, while for younger, unmarried women this is less taboo.[85] These practices are largely associated with Orthodox and Hasidic Judaism. As noted above, Solomon and his family, though Orthodox, were not as conservative as Orthodoxy implies today. Nevertheless, the painting suggests an awareness on his part of these practices regarding women’s hair, which can be seen in other works by him as well. For instance, in a wood engraving showing a family celebrating the Passover seder (see fig. 7), one of a series of illustrations Solomon made of Jewish customs, the mother seated at the far left wears a headscarf, as does the young woman standing behind her, suggesting she is married to one of the men at the table. In contrast, the girls and younger women at the table have their hair uncovered. The unknown author of the essay accompanying the illustration noted that Passover serves to remind all Jewish people “that, as they were all equally in bondage, they should all equally return thanks for their redemption.”[86]

For Eaton and her mother, of course, the wearing of a headscarf would have had very different meanings. Jamaican-born, they would have been readily familiar with the varieties of headscarves worn by Caribbean women. These headscarves became fashion statements and signifiers of class, or even acted as cultural references to West African figural sculptures, drawing attention to the statuesque quality of a woman’s face and head.[87] This headdress was known as the tignon in Louisiana and in Spanish and French colonies in the Caribbean. In Jamaica it was called the tie-head and was worn predominantly by women in the multiracial community (both enslaved and free), with variants worn by enslaved African women and, when fashionable, even by some white enslavers.[88] While the tignon’s use was enforced by law as a way to identify multiracial women of color, Buckridge contends that the use of the tie-head in Jamaica was more practical: it helped protect the wearer from the intensity of the tropical sun. Nevertheless, the headdress could have coded meanings, such as signifying its wearer’s resistance to slavery, as it was deployed elsewhere in the Caribbean and in Louisiana. More significant for Buckridge, however, was the evolution of women’s fashion choices in Jamaica postemancipation, predominantly among the multiracial community who began to wear British-style Victorian fashion, such as bonnets rather than headscarves.[89]

Born in postemancipation Jamaica, Eaton may not have felt a cultural necessity to wear a tie-head and may have worn a bonnet instead. Certainly, in mid-Victorian London, women rarely went out without some form of a head covering such as a bonnet. Then again, employed as a charwoman in London, Eaton might have worn a tie-head to keep her hair clean while she worked. The point is, Eaton, a freewoman of color, had some level of choice, something her mother did not have in Jamaica. It is tempting to take that idea of choice even further, to believe that Eaton also exercised agency by deciding to pose with confidence and poise for the artists for whom she modeled, showing off her full head of hair as part of her personal identity. But in reality, as a working-class woman, she modeled to earn extra money to support her growing family. Ultimately, she was subject to the gaze of numerous artists who sought to “dress up” a figure in their paintings by working with a model who arguably represented Blackness. Nevertheless, in Solomon’s drawings, Eaton’s hair and the artist’s detailed attention to its structure, shape, and sweep are reminders to the viewer that she was a freeborn British citizen with multiracial, Caribbean origins, despite her mother’s association with slavery.

The Exhibition and the Reviews

The ninety-second annual exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts in London took place in its shared building with the National Gallery at Trafalgar Square from May 7 to July 28, 1860. The catalogue documents 1,258 works of art on view (three-quarters of which were oil paintings) made by 642 artists, only 12 percent of whom were academicians.[90] Among the works, hung Salon-style in a dense display of contemporary art, were pictures by the three Solomon siblings, painted, as the catalogue attests, in the same studio at 18 Gower Street, Bedford Square. Rebecca’s work Peg Woffington’s Visit to Triplet, no. 269 (private collection), was displayed in the Middle Room; it would become one of the most successful paintings of her career.[91] Abraham’s painting Drowned! Drowned!, no. 478 (location unknown), a moral and literary subject, was not received as well as his previous pictures exhibited at the Royal Academy.[92] This work hung in the West Room on the last wall, undoubtedly on the line (i.e., on a railing eight feet up from the floor) based on the number of works and their overall arrangement in that space.

Simeon’s painting, titled in the catalogue Moses, no. 346, was also in the West Room, but it was hung on the entry wall to the right of the last wall where Abraham’s painting was displayed. The exhibition catalogue that year specified: “The Numbers of the PICTURES follow from Left to Right; the first Number being over the Door.”[93] That meant that Solomon’s painting was the ninth sequential picture in the West Room and was installed, along with the others in this initial group of pictures, high above the line, over or very close to the top of the doorframe.[94] As a result, even with its top protruded outward to facilitate viewing from below, Moses would not have been easy to see. One critic even noted that the painting was “placed with little regard to its merit.”[95] Despite its location, the quality of the painting was distinctive enough that at least nine critics wrote about it.

In fact, Solomon’s picture might have attracted more attention because there were few other paintings with religious subjects on view. Giebelhausen has shown that only 2.5 percent of the entire number of paintings shown at the Royal Academy in 1860 had religious subjects, nearly evenly divided between those from the New Testament and those from the Old Testament but favoring those from the former.[96] This low percentage reinforces, then, Prettejohn’s proposition that the exhibition of 1860 was significant for the “public demand for serious religious painting,” with a particular focus on “modern research and thinking” that “introduced new perspectives that excited rather than undermined contemporary interest in religious pictures.”[97] The Mother of Moses was just one of these new religious paintings. There were also, for instance, three religious paintings by William Dyce (1806–64) on view. And, as noted above, there was a sensational response to Hunt’s painting The Finding of the Savior in the Temple (see fig. 12), which was on view nearby at Gambart’s German Gallery. Prettejohn and art historian Keren Rosa Hammerschlag have argued that the increase in subjects drawn from the New Testament were efforts on the part of artists to visually reclaim Christ’s historic and racial origins for their largely Protestant audience.[98] However, it is worth remembering that, in addition to Solomon’s painting, there were a number of Old Testament subjects on view, including Hagar and Ishmael (location unknown) by J. Clark (possibly Joseph Clark [1834–1926]); The Prophet Isaiah (location unknown) by George A. Patten (1801–65); and a sculpture entitled Jephthah and His Daughter (ca. 1860; Walker Art Gallery, National Museums Liverpool) by Giovanni Fontana (ca. 1821–93). Among these works, only Solomon’s was a Pre-Raphaelite painting by a Jewish artist.

Curiously, The Mother of Moses shared its subject with works by three other artists who exhibited works picturing the infant Moses, all of which were on view together in the North Room, separated from Solomon’s painting in the West Room: Moses, in the House of Pharaoh by J. D. Marshall (possibly John Dalrymple Marshall [?–1890]); The Mother of Moses by Marshall Claxton (1813–81); and The Mother of Moses Hiding, After Having Exposed Her Child on the River’s Brink by Edward Armitage (1817–96). The dates and locations of these paintings are unknown, but descriptions of the works exist in reviews. Among these artists, only Armitage had a significant career.[99] For instance, an unidentified writer for the British Quarterly Review, after noting this preponderance of paintings with subjects featuring the infant Moses, described Armitage’s painting as possessing “a very fine head . . . of his [Moses’s] mother watching from her reedy covert the fate of that frail ‘ark of bulrushes.’”[100] This author is also among the reviewers at the time who criticized Armitage, Claxton, Marshall, and Solomon for incorrectly depicting the skin color and physiognomy of the figures in their paintings: “But, with strange perverseness in every case, the mother and sister [of Moses] are far darker than Israelitish women could have been.”[101] The writer goes on to describe Claxton’s figures as “not quite so Egyptian, but still the mother is actually swarthy”; Marshall’s mother of Moses as “just as dark as the princess”; and Armitage’s figures as “scarcely Jewish enough,” adding that, while the artist “properly avoided the Egyptian type of feature,” Jochebed never would have worn Egyptian dress.[102] The harshest criticism was reserved for Solomon:

This blunder, singularly enough, is most glaring in the “Moses” (346) of Mr. Simeon Solomon. Here is the anxious mother gazing with tender earnestness on the infant in her arms, while the sister stretches up, leaning on her mother’s arm more easily to see him; but not only does the mother’s complexion, the genuine red-brown, but the contour of her features, belong to the Egyptian race, while the very shape of Miriam’s head is the long narrow type, with the almost woolly hair, too, of the Copts of the present day.[103]

It is significant that this reviewer criticized the physiognomy and skin color of the figures in these paintings, which says more about his expectations that the Israelites should be white than about how the artists painted them as people of color.

Of all the reviews, the Athenaeum, as noted above, was extraordinary in its high praise of Solomon and his artistry, declaring that he “will be a man of mark” based on his painting The Mother of Moses. But this review was also the most critical of his choice of model and her physical features, referring to Eaton as “far too black,” chiding Solomon for having failed to “eliminate that appearance,” and pointing out that the model was “not . . . educated in the constraint of civilized life.”[104] This criticism of the model was also apparent in other reviews. For instance, Frederic George Stephens (1827–1907), one of the original members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood who abandoned painting for art criticism, began by looking favorably upon Solomon’s painting. He remarked that “the colour throughout this picture is extremely good, the varying textures of the dresses excellently rendered, and the accessories all displaying thought and originality,” but then he stated bluntly that the faces of the two women are “a little too dark.”[105] Other critics also sought to categorize the ethnicity or nationality of the models/figures. A writer for the Daily News, in a backhanded compliment, wrote: “The artist has avoided all taint of conventionality by painting low-type oriental physiognomies and accessories, but although the expressions of the mother and young Miriam are appropriate, the general expression is mean.”[106] The Art Journal, rarely favorable to the Pre-Raphaelites, saw “an oppressive influence in this work that sinks the spirits” and went on to criticize the figures as “rather Egyptian than Jewish.”[107] The Critic was complimentary in its appraisal of the female figures, even if its reviewer, too, resorted to ethnic typology: “both of strongly marked Oriental features—in fact Indian—type face and form, not beautiful, but exceedingly characteristic and impressive; more suggestive of the actual mother of Moses than any study from European women could be.”[108]

This last comment was, of course, Solomon’s point: to depict with more naturalism the ancient Israelites in Egypt, without relying on idealized (i.e., white) European or British models. The writer for the British Quarterly Review was the most scathing, so harsh, in fact, that the novelist and critic William Makepeace Thackeray came to Solomon’s defense:

[O]ne of the pictures I admired most at the Royal Academy is by a gentleman on whom I never, to my knowledge, set eyes. This picture is No. 346, Moses, by Mr. S. Solomon. I thought it had a great intention. I thought it finely drawn and composed. It nobly represented, to my mind, the dark children of the Egyptian bondage, and suggested the touching story. My newspaper says: “Two ludicrously ugly women, looking at a dingy baby, do not form a pleasing object;” and so good-bye, Mr. Solomon. Are not most of our babies served so in life? . . . So cheer up, Mr. S. S. It may be the critic who discoursed on your baby is a bad judge of babies. When Pharaoh’s kind daughter found the child, and cherished and loved it, and took it home, and found a nurse for it, too, I daresay there were grim, brickdust-coloured chamberlains, or some of the tough, old, meagre, yellow princesses at court, who never had children themselves, who cried out, “Faugh! the horrid little squalling wretch!” and knew he would never come to good; and said, “Didn’t I tell you so?” when he assaulted the Egyptian. Never mind then, Mr. S. Solomon, I say, because a critic pooh-poohs your work of art—your Moses—your child—your foundling.[109]

Note that even Thackeray saw Solomon’s figures as appropriately representing, in his mind, the “dark children” of Israel.

Regardless of their opinions about Solomon’s success or failure as an artist, these critics blatantly reveal their true concern: a near-obsessive panic over the presence of Blackness in the depiction of a biblical subject. While the skin color and physiognomy of Solomon’s model for Jochebed and Miriam arguably reflect his effort to depict naturalistically a devout, enslaved woman under duress, the figures also represent the Orientalist qualities of an important biblical story: the Israelites as a people of color enslaved in Egypt. Simultaneously, the presence of the model Eaton, a woman of color, the daughter of a formerly enslaved mother, and a mother herself, reminds the viewer, then and now, that this painting is one of numerous important works of art from the time that drew attention to Blackness as central to the subject of slavery. Ultimately, the painting’s achievement is its ability to operate on multiple levels, utilizing the traditions of history painting and a biblical narrative to reflect not only the artist’s own Jewish cultural experience in London but also debates over slavery and abolition for Black people at that time.

Coda: The Artist as a Racist?

Recently, a previously unknown sketch attributed to Simeon Solomon, discovered in a small archival collection of his letters at the Getty Research Institute, has come to light. Undated and unsigned, the pen-and-ink drawing resembles stylistically other comical sketches by the artist. Solomon, like Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones (1833–98), was known among his contemporaries for his efforts at humor and his satirical sketches. Examples of his cartoons include witty illustrations to stories and poems in his early sketchbooks (held in the Jewish Museum, London; and the Mishkin Museum of Art, Ein Harod, Israel) as well as undated, stand-alone drawings such as A Pre-Raphaelite Studio Fantasy (private collection), mimicking art critics and the traditions of the Royal Academy, and Sir Galipot Bearing the Holy Gruel (fig. 24), poking fun at Arthurian lore popular in the Victorian period. At times he included self-deprecating caricatures of himself in letters he wrote to friends and colleagues, such as the painter Holiday and the collector Eleanor Tong (later Mrs. William Coltart).[110] Solomon also wrote satirical monologues on scientific subjects that he recited at parties, and he reportedly may have written a play poking fun at Cleopatra’s Needle after its erection in London.[111] This newly discovered drawing, however, is problematic for its blatant racial overtones.

The drawing (fig. 25) shows a man seated in an interior with two women. The man has a mustache and is bald on the top of his head. Photographs from the later 1860s suggest Solomon’s hair was balding by that time. The woman on the left has a voluminous body dominated by her day dress, while the second one appears more statuesque in a cinched bodice and crinoline. She leans toward the woman on the left as if seeking to take care of her. The faces of both women have sharp diagonal lines running across them (more so in the case of the larger woman), suggesting dark skin color, while the man’s face has no lines. The taller woman’s dress and the man’s suit are covered in similar diagonal lines, likely to indicate the dark color of the fabric. The man asks, “Don’t you think so / Mrs. L x x ?” and the larger woman replies, “I donno / massa.” The woman’s use of slang is meant to show her lack of education, while addressing the man as “massa” (master) indicates her assumed subordination to him as possibly having been a formerly enslaved person. In looking at this drawing, I cannot help but speculate that the man is Solomon and the two women Fanny Eaton and her mother Matilda Foster, although there is no factual basis for this conjecture.

This drawing shares similarities with what Bindman has noted about racial tropes in British satirical cartoons such as the one published in the series Life in Philadelphia (fig. 26), in which Black people are parodied wearing elaborate fashions lacking in taste and speaking with poor pronunciation, revealing their “aspiration beyond one’s social rank” which cannot “disguise the ‘real’ nature of the person, but only produce an effect of humorous incongruity.”[112] In Solomon’s drawing, “Fanny” seems more comfortable in her clothes than “Matilda,” whose body language and verbal skills reveal her inability, as a (presumably) formerly-enslaved person, to fit comfortably within middle-class society. Indeed, the dialogue becomes more important than the image, providing meaning beyond what otherwise might seem like a comical domestic scene and reinforcing how text is a powerful tool in drawings and cartoons to elucidate otherness and social class. Literary scholar Frank Felsenstein has pointed this out in particular in British caricatures of Jews speaking with lisps and other affectations.[113]

In Solomon’s undated drawing, Mrs. L. is not identified as Mrs. Foster. Yet only two identified Black women, Eaton and her mother, intersected with his life and art, one of whom had formerly been enslaved and the other of whom was reportedly a statuesque model whose appearance, as Rossetti once observed, was not unlike that of Jane Morris (1839–1914), another famous Pre-Raphaelite model.[114] If this drawing depicts Eaton and her mother seated with Solomon, it implies he may have had a more social relationship with the two of them together than the transactional one he had with Eaton alone as a model. However, it also suggests that Solomon has placed himself in the reprehensible role of “master,” a position that not only contradicts his own life as a Jewish man whose cultural legacy included the ancient Israelites enslaved in Egypt but also reinforces the standard, accepted ethos of most white Victorians, including abolitionists, who believed they were superior to people of color.

This role of “master,” then, suggests a strikingly different artistic narrative than the one I have argued above—that Solomon’s head studies of Eaton are intimate, naturalistic, and sympathetic portrayals of her as a Black woman, and that the painting is one of a number of contemporaneous works of art in support of emancipation that draw attention to the plight of Black people enslaved in the US South—even if we acknowledge that this drawing was intended for private distribution and the painting for public consumption. Regardless of whether Eaton and her mother are actually depicted in this drawing, it is still insensitive to, and disparages, Black people, an apt reminder from Felsenstein that images such as this “reveal as much, if not more, about endemic English attitudes than they do of the ethnic minority they attempt to caricature.”[115]

In 1987, art historian Linda Nochlin published a groundbreaking essay that called attention to Edgar Degas (1834–1917)—Solomon’s contemporary—as an anti-Semite, exploring works of art by the French artist in which one might find evidence of his anti-Semitism and evaluating its relevance thereof.[116] As she noted later when looking back at this essay, “the visual evidence is ambiguous, the life apparently at odds with or irrelevant to the art,” yet “it is an apparent anomaly which challenges the whole notion of an unproblematic identity between biography and work.”[117] Nochlin did not want us to stop appreciating Degas; rather, she wanted scholars to better understand that artists of the past need to be examined critically, lest we allow ourselves to become blind to their humanity. Commenting on Nochlin’s essay, Bindman more recently has noted that artists like Degas and his peers were “people [who] were invariably inconsistent, at different ages and times, and between their private and public life.”[118] Solomon, then, was no different. So, can we pass judgment on him today as a racist based on one very disturbing drawing, possibly made as a joke for sharing with friends, when no other evidence by him or about him shows him to have had racist beliefs or engaged in racist practices?

Among the Pre-Raphaelites and their contemporaries, the art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900) was known for his racist and proslavery views, for which many disparaged him. In contrast, Rossetti and his family, colleagues, and friends, are documented as being largely opposed to slavery and supportive of emancipation. But Rossetti was also known for what Marcus Wood has called “‘catch 22’ racism,” derisive language and behavior against Black people meant as a form of humor.[119] Burne-Jones, Rossetti, Swinburne, and others referred to Solomon as their little “Jewjube,” a clearly anti-Semitic nickname, and Burne-Jones was known to have made anti-Semitic cartoons as well.[120] Solomon was also caricatured in the satirical magazine Punch with a large nose (which he did not have). The US artist Elihu Vedder (1836–1923) recounted how Solomon suffered divine consequences (almost being struck by lightning) for having eaten bacon (reflecting the perpetual stereotype of Jewish desire for forbidden foods such as pork and the association of Jews with pigs).[121] We do not know how Solomon responded to these jokes, but his ongoing association with these friends and colleagues suggests he accepted them.

With regard to abolition, I would argue that Solomon likely shared the Pre-Raphaelites’ support of emancipation. Moreover, his Orthodox Jewish upbringing; the religious legacy of Israelite slavery in Egypt reaching back to the time of Moses; and the contemporaneous struggles of Jews in Victorian England to be treated as equals in British society all arguably reinforced his proactive stance for the end of slavery for Black people. That said, in this article I have made a conscious effort not to directly argue what Solomon personally may have intended in painting The Mother of Moses. Rather, I have proposed scholars give renewed attention to this work of art because, like other contemporaneous British and European paintings and sculptures depicting people of color, it is directly concerned with Blackness and slavery. This is evident in the painting’s Pre-Raphaelite attention to details discussed earlier in this article; its biblical narrative about the Israelites; and the fact that its main figures were painted directly from the model Fanny Eaton, who was born a freewoman in Jamaica, the daughter of a formerly enslaved woman. The Mother of Moses is undoubtedly one of the most important works of art painted and exhibited in London in 1860. It altered the career of this nineteen-year-old Jewish artist through his skillful combination of biblical history with contemporary events, drawing attention to Jewish emancipation in London and the lives of people “far too black” who were still enduring the ongoing horrors of slavery.

A correction to endnote 44 was made on April 3, 2024: an earlier version stated that Keren Hammerschlag “misreads the model for Solomon’s painting as a Jewish woman.”

Acknowledgments

I have been formulating this article for nearly two decades, a span of time that has allowed my research and personal reflections on its topic to evolve in many ways, not the least of which relates to new and evolving understandings and interpretations of racism, anti-Semitism, and homophobia. I am humbly grateful to the numerous scholars whose groundbreaking work, cited in the notes below, has helped me formulate my ideas about Solomon and Eaton. This project on The Mother of Moses first took form as a seminar paper on “exoticisms” in Western art under the guidance of Judy Sund, whom I thank for her early feedback and her encouragement to develop the paper into an article. I have given presentations on aspects of this topic at the conference Pre-Raphaelitism Past, Present and Future (Oxford University, 2013) and as a guest speaker at the Delaware Art Museum in Wilmington (2023). My thanks to the audience members whose questions and responses helped generate more ideas. My heartfelt gratitude goes out to Carolyn Conroy and Sophie Lynford for their excellent feedback on early drafts of this article; to Brian Eaton for his steadfast support and encouragement of my work over the years related to his great-grandmother, who died a century ago in 1924; to Carol Jacobi and Margaret D. Stetz for our insightful conversations on Pre-Raphaelite art; and to the anonymous peer reviewers and the editorial team at Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide for their advice and assistance in bringing this project to publication.

Notes

Epigraph: “Royal Academy,” Athenaeum, May 12, 1860, 654.

[1] Literature on the Pre-Raphaelites is vast, but among the more recent overviews are Tim Barringer, Reading the Pre-Raphaelites (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999); Elizabeth Prettejohn, The Art of the Pre-Raphaelites (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000); Tim Barringer, Jason Rosenfeld, and Alison Smith, Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design, exh. cat. (London: Tate; New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012); and Jan Marsh, Pre-Raphaelite Sisters, exh. cat. (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2019).

[2] On Jewish Emancipation, see Abraham Gilman, The Emancipation of Jews in England, 1830–1860 (New York: Garland, 1982). See also Todd M. Endelman, The Jews of Britain, 1656 to 2000 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), esp. chap. 3, “Poverty to Prosperity (1800–1870),” 79–124.