New DiscoveriesAugustus Saint-Gaudens, Antinous, 1874

by Stefania Corsini, Etta M. Madden, and Caterina Y. Pierre

Stefania Corsini

Independent Scholar, Pistoia, Italy

Email the author: stecorsini1[at]gmail.com

Etta M. Madden

Professor Emerita, Missouri State University

Email the author: ettamadden[at]missouristate.edu

Caterina Y. Pierre

Professor, City University of New York, Kingsborough Community College

Visiting Associate Professor, The Pratt Institute

Email the author: caterina.pierre[at]kbcc.cuny.edu, cpierre[at]pratt.edu

Citation: Stefania Corsini, Etta M. Madden, and Caterina Y. Pierre, “Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Antinous, 1874,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.1.6.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s (1848–1907) bust of Antinous (1874) (fig. 1), listed as unlocated in the catalogue raisonné of John H. Dryfhout’s The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1982; reprinted in 2008), rests today on a marble-topped stand in a salone (living room) of the Villa Papiano in Tuscany.[1] The villa, a private residence, was once owned by the Philadelphia art collector and philanthropist Laura Towne Merrick (1842–1926) (fig. 2), who commissioned Antinous, a copy of the head and shoulders of the ancient sculpture of Antinous at the Capitoline Museum in Rome (fig. 3). How did Saint-Gaudens’s Antinous come to be described as unlocated? How did it arrive at the Villa Papiano in the hills of Tuscany? And how has the sculpture recently come to light? The answers to these questions, the subject of this essay, speak to the role of women art patrons and their contributions to the development of Saint-Gaudens’s career as well as to the importance of women’s art networks, both in the nineteenth century and today.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (fig. 4) is today considered one of the most important sculptors of the Beaux-Arts period (1830–1920) in the United States. Born in Dublin, Ireland, to an Irish mother and a French father, he was raised in New York. By the age of thirteen, he entered an apprenticeship with a cameo carver, Louis Avet (active ca. 1849–84). Saint-Gaudens later attended Cooper Union and the National Academy of Design, both in New York, to continue his artistic training before traveling to Europe. In 1867 he arrived in Paris, where he studied at the Petite École until he was admitted into the École des Beaux-Arts (in 1868) and aligned himself with François Jouffroy (1806–82). He remained in Paris for three years, but the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 obliged him to travel to Rome, a city where he stayed for many years and to which he frequently returned within the decade. It was in Rome that Saint-Gaudens made many important contacts, particularly with expatriate women such as Merrick and her friend, the writer and foreign correspondent Anne Hampton Brewster (1818–92) (fig. 5), both of whom would become essential sources of support in his early career.[2]

This article’s three authors—one an art historian with a specialty in nineteenth-century sculpture (Caterina Y. Pierre), one a literary historian focused on US writers in nineteenth-century Italy (Etta M. Madden), and one a native of Tuscany whose career teaching English reflects an interest in US expatriate life (Stefania Corsini)—collaborated to bring this story of Antinous to eyes beyond the Villa Papiano. Corsini, a resident of Pistoia, the province which is also home to the Villa Papiano, followed her fascination with Merrick’s life in Tuscany to research and write the biography entitled Miss Merrick: L’Americana che visse a Papiano.[3] During that process, Corsini learned of Madden’s publications on Brewster, who visited galleries with Merrick during her first stay in the Eternal City.[4] Brewster also supported the career of Saint-Gaudens by publishing descriptions of his studio work in Rome in US newspapers such as the Boston Daily Advertiser and the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin and by introducing him to wealthy patrons such as Merrick.[5] After learning of the Saint-Gaudens sculpture and visiting the Villa Papiano with Corsini, Madden reached out to Pierre, whom she knew was an expert on sculpture of the era. Almost a decade earlier, Madden and Pierre had met at the American Academy in Rome, where they were each conducting independent research projects.[6] This collaborative article, then, reflects the power of networking, similar to the intertwined relations which brought about Saint-Gaudens’s creation of the Antinous sculpture for Merrick in the nineteenth century and the rise of his career, fostered by Brewster’s writing and Merrick’s patronage. Two women advanced the creation of Antinous in 1874, and three women wish to contextualize it and reinsert it into the art historical record in 2024, one-hundred and fifty years later.

The evidence of Merrick’s commission to Saint-Gaudens and Brewster’s role in that commission lies in letters, an account book, and newspaper publications, many of which were either misread by Saint-Gaudens scholars (such as the account book—more on that below) or were never read by them (for example, Merrick’s letters and Brewster’s news publications). This evidence, and additional information of what travel to Italy meant for US women in the nineteenth century, round out the story of how Saint-Gaudens’s Antinous made the journey from Italy to Philadelphia and finally back to Italy to the Villa Papiano, where it exists today.

Relocating Antinous through Textual and Visual Evidence

Saint-Gaudens’s son, Homer Saint-Gaudens (1880–1958), recounted in The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1913) that his father had received commissions, without naming the patron, for “copies of antique figures and busts,” including one of Antinous and another of Apollo Belvedere, during his second stay in Italy from 1873 to 1875.[7] In his discussion of an unlocated Apollo Belvedere, ordered by Merrick between 1873 and 1874, Dryfhout, in The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, asserted that

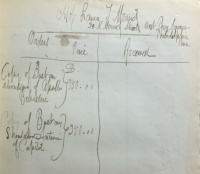

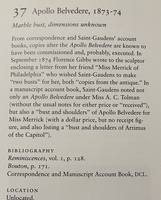

in 1874 Florence Gibbs wrote to the sculptor enclosing a letter from her friend “Miss Merrick of Philadelphia” who wished Saint-Gaudens to make “two busts” for her, both “copies from the antique.” In a manuscript account book, Saint-Gaudens noted not only an Apollo Belvedere under Miss A. C. Tolman (without the usual notes for either price or “received”), but also a “bust and shoulders” of Apollo Belvedere for Miss Merrick (with a dollar price, but no receipt figure, and also listing a “bust and shoulders of Artimus of the Capitol”).[8]

To clarify Dryfhout’s error (he reads the word “Antinous” as “Artimus” in Saint-Gaudens’s account book), we are reproducing both the relevant account-book notes and the entry for Apollo Belvedere in Dryfout’s catalogue raisonné (figs. 6, 7). As seen in figure 6, the first artwork listed on the account-book page for Merrick’s orders is a “Copy of Bust and Shoulders of Apollo Belvedere,” to be sold for $350; the second artwork mentioned on the same page, also for the price of $350, is a “Copy of Bust and Shoulders [of the] Antinous of Capitol.” Nowhere on this page is there an order for an Artimus, and thus it also seems evident that Dryfhout misread the account book. There is also no Greek god named Artimus, unless Dryfhout misspelled the word “Artemis,” the Greek goddess of the hunt whose Roman counterpart was Diana. Therefore, we conclude that Merrick ordered two busts and shoulders from Saint-Gaudens, one after the Apollo Belvedere and the other after the Antinous of the Capitol[ine Museum], for $350 each. While we have not located the copy of the bust and shoulders of the Apollo Belvedere ordered by Merrick, we have located Merrick’s bust and shoulders of Antinous, at the Villa Papiano.

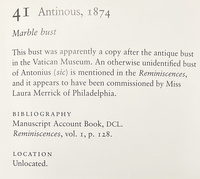

Although Dryfhout names an Artimus in the entry for Apollo Belevedere in The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (see fig. 7), he does acknowledge that Merrick also seems to have ordered an Antinous.[9] In the catalogue entry for Antinous (fig. 8), Dryfhout says that a bust of Antinous was mentioned in Reminiscences and “it appears to have been commissioned by Miss Laura Merrick of Philadelphia.”[10] Why should Dryfhout have cited Reminiscences when the account book indicates that Merrick definitely ordered an Antinous? Dryfhout may have believed there to be another Antinous after an antique bust in the Vatican Museum, but he gives no further evidence of the existence of this second Antinous. However, it seems more likely that Dryfhout misread Saint-Gaudens’s handwriting in the account book.

We invite readers to compare figures 1 and 3 below as visual evidence supporting our claim that Augustus Saint-Gaudens made Merrick’s Antinous as a copy after the Capitoline Antinous. Both versions have the same turn of the head and neck to the sculpture’s right; a slight tipping back of the shoulders, creating a V-shaped clavicle; and short-cropped, curly hair that ends just below the ears. One can also see in both a tipping down of the head so that the eyes seem to look down and away from the body.

Fig. 1, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Antinous, 1874. Marble. Private collection, Pistoia. Artwork in the public domain; photograph courtesy of the Venturini Collection, Pistoia.

Fig. 3, Capitoline Antinous, Roman copy of a Greek statue, 2nd century, originally from the Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli. Marble. Capitoline Museums, Rome. Artwork in the public domain; available from: Wikipedia.

Dryfhout suggests in the catalogue entry illustrated in figure 8 that Saint-Gaudens made a bust of Antinous after a bust of Antinous found at Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli in 1790, located today at the Vatican Museums (fig. 9).[11] While Saint-Gaudens may have made such a work for someone else, it seems clear that the Vatican Antinous was not used as the model for the bust of Antinous made for Merrick (figs. 10–12). In the former work, the face is fuller and the long curls of hair extend well below the ears. The head is turned towards the sculpture’s left and the head is held straight. The gaze is focused forward, not down and to the right as in both Antinous by Saint-Gaudens and the Capitoline Antinous. We maintain that there is a clear visual connection between Saint-Gaudens’s Antinous made for Merrick and the Capitoline Antinous. In the account book, Saint-Gaudens notes that Merrick ordered a “copy of bust and shoulders [of the] Antinous of Capitol,” and that is exactly what she received.

It is not surprising that Merrick might have wanted a copy of the antique Capitoline Antinous, since it was a main attraction of the Capitoline’s collection in the nineteenth century and was widely recognized for its beauty.[12] In addition, it was common for US patrons of the period like Merrick to commission copies after the antique from young artists like Saint-Gaudens as high-end souvenirs, and these artists, who were seeking work and connections, were keen to oblige. As Thayer Tolles has noted, “These unsigned works were representative of the type of souvenirs that cultivated Grand Tourists purchased to memorialize their visits to the Eternal City.”[13] During his five-year stay in Italy from 1870 to 1875 (which included a brief return to New York in 1872–73), Saint-Gaudens made many busts in marble after ancient works he saw there as well as portrait busts of his early patrons. Antinous fits among other busts of classical influence and copies after the antique that Saint-Gaudens completed at this time, including Young Emperor Augustus (now called Gaius, 1872–73), commissioned by New York City Attorney Montgomery Gibbs and Secretary of State William M. Evarts; Marcus Junius Brutus (1873), sculpted for the diplomat Edwin W. Stoughton; Cicero (1873–74), likely made for Evarts; Demosthenes (1873–74), made for Evarts; Apollo Belvedere (1873–74), commissioned by Merrick and possibly also by Miss A. C. Tolman; and Venus de Medici (1873–74), ordered by Tolman.[14] In the chronology section of The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Antinous is placed at the end of this series of copies after the antique, which Dryfhout dated to December 1873. Later in the same text, Antinous is dated to 1874.[15]

No artist, however, would ever become famous from making copies after the antique. Once Saint-Gaudens showed the clay model of his Hiawatha (1872–74) to Gibbs, the artist’s copying days came to an end. Gibbs vowed to support the completion of Hiawatha, and once it was sold in New York in 1874 to Governor Edwin D. Morgan, Saint-Gaudens’s career truly began. He did not need to return to making copies after antique works for patrons in the United States.[16]

Laura Towne Merrick: A Love Affair with Italy and Antiquity

Merrick, the daughter of Samuel Vaughan Merrick (1801–70) and Sarah Thomas (1800–81), was the last of seven children born into a privileged Philadelphia family, with one home in Penn Square (30 North Merrick Street, given as Merrick’s address in Saint-Gaudens’s account book) and another in Germantown, on an estate called Torworth. Her father, successful as an engineer and businessman in the iron, railroad, and gas industries, was also a leader in Philadelphia’s cultural institutions, including the American Philosophical Society and the Franklin Institute, of which he was a founding member. The Merrick family also was known for contributing to the construction of hospitals and schools.[17] We know little about Merrick in her early years, other than this family background and two photos that show her with curly hair and an oval face and wearing elegant clothing.[18] But letters, diaries, and other records do provide windows into Merrick’s time in Italy, beginning when she was in her late twenties. These documents suggest that Merrick’s travel, as much as her family’s history of supporting cultural institutions, prompted her to commission and collect artworks related to her travels abroad. She visited Italy for the first time sometime between June 1869 and January 1870 and returned in the early 1880s. Records document her time in Tuscany’s Florence and Bagni di Lucca in 1883 and 1884, respectively, with the purchase of the Villa Papiano in 1886. In 1905 Merrick purchased a sumptuous villa in Rome’s via Sallustiana, not far from the via Veneto. Then, in 1911, she sold the villa in Rome and purchased a villa on viale Milton in Florence, but she continued to spend summers at the Villa Papiano until her death in July of 1926. Her body was returned to the United States for internment in Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery, alongside other family members.[19]

Merrick’s first trip to Italy was part of a typical Grand Tour itinerary, with stops in London, Paris, Brussels, and Heidelberg as she made her way south to Florence and Rome. A letter of introduction from her family minister, written in June of 1869, as well as several other family letters suggest that she went abroad for the sake of her body as well as her mind. She suffered from depression and weakness. Family friend and physician, Silas Weir Mitchell (1829–1914), well-known for the “rest cure” he often prescribed female patients diagnosed with the nervous disorder neurasthenia, instead advised Merrick to travel.[20] Saint-Gaudens also knew Mitchell, and later created a bronze bas-relief portrait for him in 1884, another example of these close networks of patronage.[21]

During her time in Rome, Merrick wrote home about her gallery visits, prompting her mother to respond to Merrick’s “enthusiasm” for the Apollo Belvedere she had seen in the Vatican Museums.[22] In the absence of Merrick’s original letter to her mother, and with only Sarah’s brief commentary about the gallery visit available today, we know nothing about thoughts she may have shared about the antique Antinous at the Capitoline Museum. However, we know more about Merrick’s gallery visits because they were arranged by her fellow Philadelphian Brewster, who published two accounts of them in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin in 1870.[23] Brewster, who had arrived in Rome only a year earlier than Merrick, had immediately thrown herself into her career as a journalist, writing at least twice monthly on cultural and political events there. One of her first publications while she lived abroad was “American Artists in Rome,” published by Lippincott’s Magazine in early 1869.[24] In fact, from her arrival in November 1868 through the time of that publication, Brewster lived with another Philadelphian, the artist and poet Thomas Buchanan Read (1822–72).[25] Soon after, she wrote about the gallery visits with Merrick.

In February of 1870, Merrick and Brewster, along with Merrick’s traveling companions Miss Bergwin and Miss McCrea (Brewster does not provide their first names), visited the Villa Ludovisi on the Pincian Hill, not far from where Merrick would later buy a villa. There they observed in the sculpture gallery Polycletus’s head of Juno, then Mars in repose, followed by the group of Dionysos and Akratos, and Pallas of Antiochus of Athens. “But the wonderous bronze of Julius Caesar was . . . most suggestive to each of us,” Brewster summarized.[26] After their time in the sculpture gallery, the group went to see Guercino’s Aurora and other frescoes in the casino, before ending their visit with a view of the city and the surrounding countryside from the rooftop terrace.[27] Italy and its classical antique treasures were an escape for both Merrick and Brewster, who found in Italy a profound beauty that was unlike anything that their native Philadelphia could offer at the time.

Later in February, Brewster wrote of a much earlier visit to the Vatican Galleries with Merrick and her two traveling companions, this time on a torchlight tour held in the autumn of 1869. This tour must have occurred soon after Merrick’s arrival, likely in November, since her stay in Rome only lasted three months, according to her great-niece.[28] The tour was led by the English sculptor Shakespeare Wood (1827–86). Wood, the honorary secretary of the British Archaeological Society of Rome, had recently published a pamphlet and was preparing a catalogue to assist English-speaking travelers with their visits. The group paused to examine the statue of Augustus, which had been found only a few years earlier (in 1867) at the villa of Livia, wife of Augustus, at Prima Porto; the cinerary urn of Livilla, daughter of Germanicus; a statue entitled Pudicitia, or Modesty, based on Livia’s features; and the famous Belvedere Torso.[29] None of Merrick’s thoughts about the torchlight tour appear in the article by Brewster, but her presence on the tour suggests her interest in antiquity and provides a clue as to why she would have commissioned copies of antique works from Saint-Gaudens only a few years later.

Merrick did note, however, her regard for Brewster’s assistance during her time in Rome, remembering it four years later when she wrote from Philadelphia to Saint-Gaudens, then living in Rome: “When you see Miss Brewster will you not give her my love. . . . Miss Brewster was so kind to me while in Rome that much of my pleasure was owing to her.”[30] This letter is evidence that Saint-Gaudens was in direct contact with Brewster in 1874, so much so that Merrick had confidence he would see the writer and relay Merrick’s fond message. At the time of the letter, Saint-Gaudens lived and worked near Brewster. Brewster wrote about him in the Boston Daily Advertiser in September of 1874, calling him “another one of these young Americans whose industry equals his cleverness.”[31] She also wrote in detail about Saint-Gaudens’s Hiawatha and the numerous commissioned busts he sculpted in the 1870s. Of these busts, in particular, she wrote “they have the same cleverness of his other works, and evince not only artistic feeling but also that study of the form which French academy drilling gives the student, and which prevents the bust from being simply clever and superficial in its likeness.”[32] In the Boston Daily Advertiser of November 16, 1874, Brewster again wrote of Saint-Gaudens, describing his “life-size sketch” in progress of a slave lifting a baby out of a basket and placing him on a pedestal, where he is crowned king. Saint-Gaudens hoped to have it ready for the Centennial Exposition of 1876 in Philadelphia.[33]

By naming artists such as Saint-Gaudens as well as patrons, Brewster likely influenced further patronage, as readers in Boston, Philadelphia, and elsewhere, and visitors such as Merrick, sought to keep up with their contemporaries and the latest collecting trends. Similarly, through the receptions Brewster hosted in her fourteen-room apartment in the via Quattro Fontaine—not far from the Piazza Barberini and the Spanish Steps, where so many tourists lived and lodged, and where Saint-Gaudens had his studio—she helped travelers become art patrons. Potential collectors, such as Merrick, as well as the artists themselves, mingled at her twice-weekly evening affairs. These events were featured in the press and enticed future travelers and patrons.[34] We are suggesting here that it was Brewster who encouraged Merrick’s love of antiquity through visits to galleries and museums in late 1869 and early 1870, and encouraged Merrick to commission copies of antique busts from Saint-Gaudens in 1874, at precisely the time when she was publishing articles on the sculptor.

But four years earlier, before Merrick wrote to Saint-Gaudens recalling her time in Rome with Brewster, she had left Rome after only a three-month stay. Her return to Philadelphia early in 1870 likely was hastened not so much by her own desires but by her father’s illness and failing health. As a great-niece later wrote, during her time in the Eternal City, Merrick “fell in love with Italy. For the rest of her life, it drew her like a magnet.”[35] She had returned to Philadelphia with her purchases of books and images of Europe (figs. 13, 14) as well as scrapbook albums in which she had recorded her travels. These served as reminders of her time abroad.[36] Ten years later, after her parents’ deaths, Merrick would return to Italy and have “some of her possessions” sent there as well.[37] We are suggesting that one of the possessions she took back with her to Italy was her bust of Antinous by Saint-Gaudens, and that she displayed it in the Villa Papiano where it remains today. But before then, during her decade back in the United States, Merrick began communicating with Saint-Gaudens and others who were commissioning his work about her desires for sculptures based on Italy’s classical past.

Artist and Patron: Saint-Gaudens and Merrick

Merrick first wrote to Saint-Gaudens in 1874, in a letter passed along by her friend Florence Gibbs, daughter of New York attorney Montgomery Gibbs, who was credited with boosting Saint-Gaudens’s career.[38] While Merrick’s letter remains unlocated, her request to have Saint-Gaudens sculpt two busts for her—the Antinous and the Apollo Belvedere noted in Saint-Gaudens’s account book—appears in Gibbs’s letter:

When we were in the country this summer we spoke of you to our friend Miss Merrick of Philadelphia and she said she wished you to make two bust copies from the antique. I don’t still remember what they are but enclose the letter from her to you. I hope you will be able to do what she asks, as she is a great favorite of ours and we spoke so highly of you to her.[39]

We believe that Saint-Gaudens completed both busts that Merrick ordered from him. In February 1878, Merrick wrote to Saint-Gaudens from her family home on North Merrick Street in Philadelphia, acknowledging his letter to her from January 19.[40] Writing on February 21, she noted that she had “delayed answering” his letter, because, as she explained, she had been awaiting the “arrival of the bust.” The unnamed bust had been shipped from Rome via an unexpected vessel and route—on the Ohio sailing to Philadelphia rather than on the Hamburg sailing to New York. Nonetheless, it had arrived in perfect order and, beyond that, Merrick gushed to Saint-Gaudens, “it is simply perfect [Merrick’s emphasis] and more than realizes my anticipations.”[41] However, she goes on to say, “I think that you will agree with me that the curves of the figure and the drapery at the back are far more beautiful than a round column.”[42] Quite likely here she describes the head-and-shoulders copy after the Apollo Belvedere—a statue with drapery (fig. 15) in the antique version—which she commissioned at the same time and which is listed on the same account book page as the Antinous. Since the Antinous does not include drapery, we must assume that the bust to which Merrick refers in this letter is either the Apollo Belvedere that she ordered from Saint-Gaudens—that is, the first work listed in the account book on the page illustrated in figure 6 and which is still unlocated—or else it is some other undocumented bust that she may also have commissioned. We must assume from this letter that Saint-Gaudens completed both “copies of busts and shoulders” that Merrick ordered and that she did receive the Apollo Belvedere.

Merrick’s letter to Saint-Gaudens of February 21 not only includes memories of her time with Brewster and the fine treatment she received from the journalist while she was in Rome but also asks Saint-Gaudens to serve as a mediator, passing along Merrick’s regards to Brewster. Merrick’s memories of Brewster, in turn, had been prompted by the death of their mutual friend, fellow Philadelphian Mary Howell. Merrick wrote, “Tell her that since the death of our mutual friend Miss Howell I have always wanted to write about her, feeling that I knew her so well, but have hesitated fearing she might think it an intrusion.”[43]

The February letter alludes to Merrick’s knowledge of other patrons and their commissions. For example, she described the marble the sculptor had selected for the Apollo Belvedere “as perfect and spotless as any” she had seen, adding that she was “more than satisfied with it.”[44] This praise is particularly noteworthy, since Merrick was likely aware that in the case of the bust of Florence Gibbs, Saint-Gaudens had to restart the project after discovering a flaw in the marble.[45] While to our knowledge no letter from Merrick describing the Antinous exists, this letter about the Apollo Belvedere contributes to our understanding of whether Saint-Gaudens completed his two commissions for Merrick.

Later in 1878, Merrick wrote again to Saint-Gaudens, on December 8 and 15. Although these letters remain unlocated, Saint-Gaudens acknowledged them in his response to her on December 16, while he was in the United States. Always recognizing the power of patronage, he responded with an apology: “I arrived here on Tuesday and I have been so occupied since there has not been time to answer before this.”[46] As Henry J. Duffy has noted, Saint-Gaudens learned early in his career that fostering “a direct and personal relationship” with patrons garnered their increased and continued interest.[47] Exemplifying this type of relationship in his letter to Merrick, Saint-Gaudens proffered his delight at having “heard through the Misses Gibbs how finely you have placed the busts” and thanked her for “information in regard to the exhibition of my busts.”[48] The fact that Saint-Gaudens refers to busts here seems to establish that by December 1878, Merrick was in possession of both busts she had commissioned from Saint-Gaudens and that were listed in his account book.

Because Saint-Gaudens would be going to Philadelphia the next week, he offered to bring her sketches he had made—possibly of future works that might interest her. However, he explained, he also had “personal ideas not yet put into sketches” as well as sketches “so large that they would have to be seen in the studio.”[49] The letter, likely an unsent draft or a handwritten copy of a sent letter for his own records, includes a loosely drawn sketch of a series of structures and a figure (fig. 16). The comments about the sketches also reflect a vow Saint-Gaudens took following the competition in 1875 for the Charles Sumner statue in Boston, which he lost. He expressed disappointment with the committee’s decision process and was determined not to make sketches in advance of commissions.[50] The ongoing correspondence between Merrick and Saint-Gaudens, culminating in December 1878, suggests that Merrick was poised to commission additional sculptures from the artist. No record of them exists, however. Perhaps Saint-Gaudens had better and more important offers. And if Merrick’s future commissions were to have been for additional antique copies, Saint-Gaudens likely would not have been interested. While as a young sculptor it had been advantageous for him to accept commissions for copies after the antique, as he became more established and recognized for his original concepts, making such copies would certainly have been tedious. Prior to his return to the United States, he had been working on the Farragut Monument in Paris with Stanford White.[51] Merrick had referred to the Farragut work in her letter of February 1878 as well as to the family’s health: “I regret to hear of your wife’s disposition & trust that she is now entirely recovered. I suppose you are hard at work on your Farragut statue.”[52] Burke Wilkinson, in his biography of Saint-Gaudens (1985), notes that the artist was afflicted with “Roman fever” (malaria) during his January 1878 visit to Rome.[53] While commenting on health was a convention in letter writing, Merrick’s phrasing also suggests that she followed both Saint-Gaudens’s personal life and his career.

Merrick’s friendly correspondence with Saint-Gaudens captures the dreams about Italy she maintained during and after traveling abroad. After seeing classical sculptures in the Capitoline Museum, the Villa Ludovesi, and the Vatican Museums, Merrick returned to the United States with photographs in a travel album, the best remembrances that she could bring home with her. But once home, visiting and corresponding with others who had been abroad and learning more of Saint-Gaudens’s work from the Gibbs family and from Brewster, she commissioned art that she hoped would remind her of her gallery and museum visits in Rome. These commissions from Saint-Gaudens, then, are reminders of how friendships intertwined with patronage. The commissioned busts, “finely . . . placed” in Merrick’s home in Philadelphia, stood in for art she had admired in Rome. They prompted memories of her time abroad and of the people, such as Brewster, with whom she had toured and seen such works. Finally, Merrick’s letters also capture her desire to reach across the Atlantic, through correspondence with Saint-Gaudens, to connect with Brewster and Italy once again. As she concluded in the February 1878 letter to Saint-Gaudens, “Now that my health is entirely restored, I envy all those who are able to be in that noble city. . . . I think we Americans have a right to be envious of you Romans.”[54]

Conclusion: A Return to Rome with Antinous

Merrick’s memories of Rome and the memory-provoking busts of Apollo Belvedere and Antinous that she owned and that we now know Saint-Gaudens did complete for her, likely factored into her return to Italy. The decade when she was in Philadelphia after her return from Italy was full of family changes, including several deaths. Her father died in 1870, followed by the death of her sister Emile in 1878 and then her mother in 1881. Merrick then inherited her family’s country estate, Torworth, in Germantown, Pennsylvania, and the family’s home at Sixteenth and Walnut Streets in the heart of Philadelphia. Merrick “told her friends” that the latter property “was haunted by death.”[55] In 1878, she had begun donating some of the family’s porcelain china, pottery, and gallware collected from Europe and Asia to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[56] It seems Merrick was already thinking about which items she would keep close at hand before the deaths of her sister and mother. Antinous appears to have been one of those items. As her great-niece wrote, after Merrick’s parents’ deaths, she had her most important “possessions” shipped to Italy, as she prepared to return to the place she loved.[57]

Sometime after Merrick and Saint-Gaudens corresponded in 1878 and her mother’s death in 1881, Merrick departed for Italy where she became a permanent expatriate. While we do not know the exact date of her arrival in the country, she was there by October 1883, when she paid for a month’s visiting privileges in the Gabinetto Vieusseux, a private library in Florence. In the library’s membership directory, Merrick’s residence is listed as the Hotel de la Ville, an elegant, large lodging on the Lungarno Vespucci. In the summer of 1884, she spent three months in Tuscany’s Bagni di Lucca, according to membership records of its summer residents.[58] Summering in rural Tuscany must have appealed to Merrick, for late in 1886 she purchased the Villa Papiano, perched on a hilltop above the village of Lamporecchio, not far from Pistoia. She spent summers there from 1887 until her death in 1926. Over the years she bought adjacent parcels of land, increasing the size of the estate and adding a horse stable in 1891.[59] The Villa Papiano sustained some damage during World War II, but it is unclear if anything, such as Saint-Gaudens’s bust of Apollo Belvedere, was destroyed there, or if the sculpture was sold by Merrick’s heirs, who retained the villa until 1955.[60] Nevertheless, Merrick’s thoughts about the bust she received from Saint-Gaudens in February of 1878 remind us of the importance of both it and the Antinous to her connection, and reconnection, with Italy and with art. As she closed her letter to Saint-Gaudens in 1878, she noted that the bust “will be an enjoyment to myself and others as long as I live and will always give pleasure to whoever looks at it.”[61] Merrick recognized the power of art to provide enjoyment and pleasure, especially as it helped her remember her first trip to Italy in 1869–70 and the art, people, and places she had encountered there.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to the Venturini family for their kind assistance and the permissions they granted during the preparation of this article. We also wish to thank the editorial team at Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide for their suggestions throughout the editorial process, which helped us clarify our arguments. We owe a special note of thanks to Thayer Tolles, curator of sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, for reading an early draft of this article. We are also grateful to the librarians in charge of the Rauner Special Collections, Dartmouth College Libraries, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, for their assistance and the permissions they granted to reproduce materials from their collection in this article. Any errors found herein remain the responsibility of the authors.

Notes

[1] John H. Dryfhout, The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1982; facsimile repr., Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2008), 6. While Augustus Saint-Gaudens preferred to spell his name without the hyphen, practically every scholar except Burke Wilkinson has used the hyphen. We use the hyphen herein as in standard practice but acknowledge that this was not always the artist’s preference. See Burke Wilkinson, Uncommon Clay: The Life and Work of Augustus Saint Gaudens (New York: Dover, 1992), xvii.

[2] Basic biographical information on Saint-Gaudens’s early life and studies was derived from “Saint-Gaudens, Augustus,” Grove Art Online, last updated July 25, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T075107 [login required].

[3] Stefania Corsini, Miss Merrick: L’Americana che visse a Papiano (Rimini: Pezzini Editore, 2017).

[4] Etta M. Madden, Engaging Italy: American Women’s Utopian Visions and Transnational Networks (Albany: SUNY Press, 2022); Etta M. Madden, “American Anne Hampton Brewster’s Social Circles: Bagni di Lucca, 1873 and Roman Rodolfo Lanciani,” in Questioni di Genere: Femminilità e Effeminatezza nella Cultura Vittoriana, ed. Roberta Ferrari and Laura Giovannelli (Bologna: Bononia University Press, 2016), 117–44; and Etta M. Madden, “Anne Hampton Brewster: Nineteenth-Century News from Rome,” All Things Italy (blog), November 21, 2018, https://ettamadden.com/blog/anne-hampton-brewster-news-rome-italy/. See also Anne [Hampton] Brewster, “Letter from Rome,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, March 3, 1870; and Anne [Hampton] Brewster, “Letter from Rome,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, April 1, 1870.

[5] Brewster, “Letter from Rome,” March 3, 1870; Brewster, “Letter from Rome,” April 1, 1870; Laura Town Merrick to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, folder 31, box 13, series 1, ML-4, Rauner Special Collections, Dartmouth College Libraries, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH (hereafter: RSC, Dartmouth College); Anne [Hampton] Brewster, “Italy,” Boston Daily Advertiser, September 29, 1874, 2; and Anne [Hampton] Brewster, “Italy,” Boston Daily Advertiser, November 16, 1874, 2.

[6] Pierre’s work at the American Academy in Rome inspired her publications on Italian cemetery sculpture and works in sculpture by Italian American artists, such as “Attilio Piccirilli’s The Outcast (1904–08) and Eternal Youth (1935): Immigrant Instability and the Italian-American Experience,” Public Art Dialogue 11, no. 2 (2021): 153–79.

[7] Homer Saint-Gaudens, Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (New York: Garland, 1913), 128.

[8] Dryfhout, The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 65. Saint-Gaudens’s copy after Apollo Belvedere is listed as number 37 in Dryfhout’s catalogue.

[9] Dryfhout, The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 67. Saint-Gaudens’s copy after Antinous is listed as number 41 in Dryfhout’s catalogue.

[10] Dryfhout, The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 67.

[11] Dryfhout, The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 67.

[12] We thank the NCAW editors for making us aware of this point about the Capitoline Antinous.

[13] Thayer Tolles, Augustus Saint-Gaudens in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 9.

[14] Tolles, Augustus Saint-Gaudens in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 9.

[15] Dryfhout dates both the Apollo Belvedere bust and the Antinous bust to December 1873 in The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 4; and in John H. Dryfhout, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1848–1907: A Master of American Sculpture, exh. cat. (Toulouse: Musée des Augustins and Somogy, 1999), 209. However, he dates Antinous to 1874 in The Works of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 67.

[16] Dryfhout, The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 26–27; and Tolles, Augustus Saint-Gaudens in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 9.

[17] Corsini, Miss Merrick, 13–15, 17.

[18] Corsini, Miss Merrick, 20–21. Later photographs and family writings reinforce this early depiction of her appearance, telling us as well that Merrick had brown eyes and blond hair and was perpetually interested in her appearance, according to Mary Williams Brinton, Their Lives and Mine (Philadelphia: Mary Williams Brinton, 1972), 201.

[19] Corsini, Miss Merrick, 22, 85, 88, 91–92.

[20] See [Rev. Suddard] to Laura Towne Merrick, June 29, 1869; Samuel V. Merrick to Laura Towne Merrick, June 30, 1869, and November 29, 1869; and Sarah Vaughn Merrick to Laura Towne Merrick, September 3, 1869, and January 28, 1870. Letters are in the Venturini private archive collection in Pistoia and are quoted in Corsini, Miss Merrick, 22, 24–29. On neurasthenia and Mitchell’s rest cure, see Jennifer Lunden, American Breakdown: Our Ailing Nation, My Body’s Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman Who Brought Me Back to Life (New York: HarperCollins, 2023), 67, 69, 286.

[21] Dryfhout, The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 114.

[22] Sarah Merrick to Laura Towne Merrick, January 28, 1870, as quoted in Corsini, Miss Merrick, 43. She does not mention Antinous or the Capitoline Museum in this letter.

[23] Brewster, “Letter from Rome,” March 3, 1870; and Brewster, “Letter from Rome,” April 1, 1870.

[24] Anne [Hampton] Brewster, “American Artists in Rome,” Lippincott’s Magazine, February 3, 1869, 196–99.

[25] Madden, Engaging Italy, 99–100, 201–3.

[26] Anne [Hampton] Brewster, “Letter from Rome,” March 3, 1870. Typical of Brewster’s “Letter from Rome” articles, which were sent to the United States by post rather than by wire, the February 11 visit to the galleries was published about three weeks later.

[27] Brewster, “Letter from Rome,” March 3, 1870.

[28] Brinton, Their Lives and Mine, 201.

[29] Brewster, “Letter from Rome,” April 1, 1870.

[30] Laura Towne Merrick to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, February 21, 1878, folder 31, box 13, series 1, ML-4, RSC, Dartmouth College.

[31] Anne [Hampton] Brewster, “Italy,” September 29, 1874, 2.

[32] Anne [Hampton] Brewster, “Italy,” September 29, 1874, 2.

[33] Anne [Hampton] Brewster, “Italy,” November 16, 1874, 2. No such work matching Brewster’s description appears in Dryfhout for the years 1874 through 1876.

[34] For fourteen years Brewster shared a residence with sculptor Albert E. Harnisch (1843–after 1913), and she wrote about him as well. See Etta M. Madden, “American Anne Hampton Brewster’s Social Circles,” 117–44; and Charles Warren Stoddard, “Roman Receptions,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 15, 1878, 1.

[35] Brinton, Their Lives and Mine, 201; and Corsini, Miss Merrick, 36–37.

[36] Corsini, Miss Merrick, 43.

[37] Brinton, Their Lives and Mine, 201.

[38] Saint-Gaudens, Reminiscences, 122.

[39] Saint-Gaudens, Reminiscences, 128. Florence Gibbs to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, September 22, [1873], folder 25, box 8, series 1, ML-4, RSC, Dartmouth College.

[40] Laura Towne Merrick to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, February 21, 1878. See also Dryfhout, The Works of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 6.

[41] Laura Towne Merrick to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, February 21, 1878.

[42] Laura Towne Merrick to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, February 21, 1878.

[43] Laura Towne Merrick to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, February 21, 1878. On Howell and Brewster, see Megan Atkinson and Christiana Dobrinski Grippe, “Anne Hampton Brewster papers” (PDF), Library Company of Philadelphia, last updated September 22, 2014, 7, https://dokumen.tips/.

[44] Laura Towne Merrick to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, February 21, 1878.

[45] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to Montgomery Gibbs, May 1872, as quoted in Saint-Gaudens, Reminiscences, 123.

[46] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to Laura Towne Merrick, December 16, 1878, folder 31, box 13, series 1, ML-4, RSC, Dartmouth College.

[47] Henry J. Duffy, “American Collectors and the Patronage of Augustus Saint-Gaudens,” in Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1848–1907: A Master of American Sculpture, exh. cat. (Toulouse: Musée des Augustin, 1999), 50.

[48] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to Laura Towne Merrick, December 16, 1878.

[49] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to Laura Towne Merrick, December 16, 1878.

[50] Dryfhout, The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 27.

[51] Duffy, “American Collectors and the Patronage of Augustus Saint-Gaudens,” 210.

[52] Laura Towne Merrick to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, February 21, 1878. The authors are grateful to Brian Hack for his assistance in deciphering this letter.

[53] Wilkinson, Uncommon Clay, 93.

[54] Laura Towne Merrick to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, February 21, 1878.

[55] Brinton, Their Lives and Mine, 201.

[56] The items had first been on display in the museum’s Memorial Hall for the city’s Centennial Exposition in 1876. Following the exposition, they never returned to a Merrick home. Brinton, Their Lives and Mine, 201.

[57] Brinton, Their Lives and Mine, 201.

[58] Corsini, Miss Merrick, 54–56.

[59] Corsini, Miss Merrick, 90.

[60] Corsini, Miss Merrick, 103.

[61] Laura Towne Merrick to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, February 21, 1878.