The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Rudolf von Alt und seine Zeit: Aquarelle aus den Fürstlichen Sammlungen Liechtenstein (Rudolf von Alt and his Time: Watercolors from The Princely Collections of Liechtenstein)

Albertina, Vienna

February 16–June 10, 2019

Catalogue:

Klaus Albrecht Schröder, ed., with texts by Anna Hanreich, Stefanie Hoffmann-Gudehus, Johann Kräftner, and Werner Telesko,

Rudolf von Alt und seine Zeit: Aquarelle aus den Fürstlichen Sammlungen Liechtenstein (Rudolf von Alt and his Time: Watercolors from The Princely Collections of Liechtenstein).

Vienna and Cologne: Albertina/Wienand, 2019.

197 pp.; 167 color and 14 b&w illus.; notes & references; checklist.

€36 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-3-9504670-3-1 (museum edition); 978-3-86832-507-2 (trade edition)

Once upon a time in Austria, an ancient noble family—the Liechtensteins—owned a number of castles but possessed no territories directly under the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor. This made them ineligible for a seat and a vote in the Imperial Council (Reichsrat). Johann Adam Andreas I von Liechtenstein (1657–1712) took the first important steps to advance the geopolitical position of the family. He purchased the dominion of Schellenberg in 1699 and in 1712, months before he died, acquired the nearby County of Vaduz, a property on the Swiss border some 327 miles west of Vienna that offered the status of imperial immediacy (Reichsunmittelbarkeit). Johann Adam Andreas I’s successor, Anton Florian (1656–1721) served Emperor Charles VI during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14). The ruler fulfilled the wish of his loyal courtier on January 23, 1719, by merging Schellenberg and Vaduz into a sovereign principality of the Holy Roman Empire and making Anton Florian the first Prince of Liechtenstein.

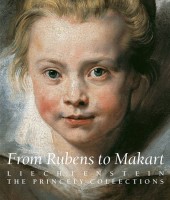

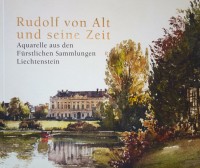

To celebrate three centuries of the Principality in 2019, the Albertina in Vienna mounted a two-part exhibition: a splendid selection of treasures from the Liechtenstein art holdings, one of the world’s largest private art collections. The first part, From Rubens to Makart: Liechtenstein, The Princely Collections, shown in the museum’s Kahn Galleries, was comprised of approximately a hundred paintings and sculptures (fig. 1). Nearly a hundred nineteenth-century watercolors, displayed in the Albertina’s Tietze Galleries for Prints and Drawings, formed the second part of the exhibition, Rudolf von Alt und seine Zeit (Rudolf von Alt and his Time) (fig. 2).[1] Some works in the anniversary show could have been seen in Vienna after 1705 in the Liechtenstein city palace on the Bankgasse, or from 1810 until 1938 in the summer palace in the Rossau neighborhood of the ninth district. Beyond his acumen in acquiring real estate, Johann Adam Andreas I was an astute art collector, with a particular interest in architecture. He commissioned work on both Viennese palaces from the architect Domenico Martinelli (1650–1718), who brought the Italian Baroque to the imperial capital. In the twenty-first century, the elegant summer palace functioned for seven years as a private museum for displaying the still-expanding family collections.

Since the Liechtenstein Museum closed in 2012, the anniversary exhibition offered the first opportunity to see beloved masterworks by Rubens (1577–1640), Adriaen de Vries (ca. 1556–1626), Friedrich von Amerling (1803–87) and many other artists in a new context at the Albertina. Spectacular recent purchases studded both parts of the show. Most visitors attended Part One, captivated by publicity posters lining the city streets with Rubens’s portrait of his daughter Clara Serena (ca. 1616), one of Johann Adam Andreas I’s numerous works by the Flemish painter.

The Albertina, a national museum, re-opened in 2003 after a massive restoration undertaken by Director Klaus Albrecht Schröder, appointed in 1999. His exhibition programs have richly recalled the museum’s origins in the private collection of prints and drawings assembled by Prince Albert Casimir of Saxony, Duke of Teschen (1738–1822). The display of Liechtenstein masterpieces, therefore, had a special resonance in Duke Albert’s palace, a building depicted in an 1816 watercolor (now in the Albertina) by Rudolf von Alt’s father Jakob Alt (1789–1872).

In their preface to the Rubens to Makart catalogue, Klaus Albrecht Schröder and Johann Kräftner, director of the Liechtenstein princely collections in Vaduz and Vienna, point out a significant contrast in the two outstanding private collections. Duke Albert sought completeness, acquiring fine examples of works on paper through a network of knowledgeable agents and connoisseurs. As Schröder and Kräftner observe, the Liechtenstein rulers (all male patrilineal descendants), on the other hand, collected across a wider spectrum of genres and media, entirely on the basis of their individual tastes.[2] During his more than three decades of purchases for the family collections, the current head of state, Prince Hans-Adam II von und zu Liechtenstein (b. 1945), has sought out exemplary Renaissance bronzes, among them Antico’s gold-plated bronze Bust of Marcus Aurelius (ca. 1500), acquired in 2016 and featured in the anniversary exhibition. During that same year, the prince purchased a dozen watercolors by Rudolf von Alt (1812–1905) on view in the current show, as well as the one sheet in the exhibition by Alt’s younger brother Franz (1821–1914) and another by Peter Fendi (1796–1842). Two rooms in Rubens to Makart also confirm the present prince’s attachment to the nineteenth century. More than half the exhibited works from that period are recent acquisitions, ranging from Angelika Kauffmann (1741–1807) to Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller (1793–1865), as well as three paintings by Hans Makart (1840–84).

In a whimsical passage in his catalogue essay for Rubens to Makart, Kräftner compares the acquisition coups of today’s Prince Hans-Adam II with those of his predecessors, particularly with his namesake Johann Adam Andreas I. Kräftner speculates on the “penchant for bronze” that seems to run in the family, parallel at times to a weakness for pietra dura, in the collecting genome of the Liechtenstein regents.[3] Was it simply the principle of building on strengths that led Hans-Adam II in 2004 to purchase the Badminton Cabinet (1726), still the world’s most expensive piece of furniture? The Liechtensteins’ desire to secure and perpetuate their art patrimony, threatened more than once in European history, and a watchful eye on the art market are less fanciful and perhaps more convincing explanations. A much wider public, of course, can share an attraction to nineteenth-century watercolors. That this fascination survived the invention of photography—even color photography—is understandable, especially after seeing a collection of this quality. Anna Hanreich’s pertinent essay for the Albertina exhibition catalogue explores the potential rivalry of the camera and the older medium.[4]

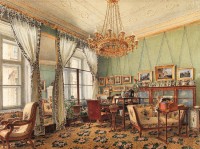

Intrepid museum-goers who entered the Tietze Galleries of the Albertina after visiting Part One of the anniversary show found an oasis of serenity. The first watercolor linked the twin exhibitions (fig. 3). During the mid-1830s, Prince Alois II von Liechtenstein (1796–1858) commissioned Josef Kriehuber (1800–76), not one of the Alts, to make family portraits. In an astonishingly intimate work of 1835, Kriehuber showed the prince with his barefoot daughter Marie Franziska (1834–1909) on his lap (fig. 4). Two oil paintings on cardboard of the same princess by Friedrich von Amerling in the adjacent Rubens to Makart show would already have beguiled most visitors: Alois II’s firstborn child asleep at age two and thoughtful at age four. The watercolor with her father, like the oil portraits of the adorable toddler, would move with the grown-up princess to her in-laws, the Trauttmansdorff-Weinsberg family. After her death, her younger brother, Prince Johann II (1840–1929), managed to purchase both the oil and the watercolor in 1927, and in 2017 Prince Hans-Adam II acquired the second oil portrait of the princess on the art market (fig. 5). Reclaiming the initial watercolor portrait and the two oils of the princess exemplifies the Liechtenstein collectors’ recurring and vigorous responses to loss, a theme traceable in both parts of the exhibition and still relevant in acquisition policy today.

On the initial wall in the room dedicated to the Liechtenstein residences in Vienna, the exhibition curators introduced its protagonist, the artist Rudolf von Alt. His earliest drawings and paintings were in the service of his German-born father, who built his artistic career in Vienna and employed his children in his workshop. Jakob Alt drew his gifted son at the easel and took him on expeditions in the mountains. Rudolf learned his trade coloring his father’s lithographs and impressed his teachers at the Vienna Academy.[5] Among Jakob Alt’s best-known pictures is the View from the Artist’s Studio in the Alservorstadt (1836; Albertina), painted in a year when Rudolf began to develop his distinctive interiors commissioned by Viennese aristocrats and industrialists.[6]

Three early interiors by Alt on the first wall of the Albertina exhibition vividly record the temporary residence of Alois II and his growing family in the Palais Rasumofsky in the Landstrasse area of Vienna. Soon after he succeeded Johann I (1760–1836), the Liechtenstein prince rented, then bought the house from the widow of the retired Russian ambassador, who died in September 1836.[7] Some thirty years earlier three remarkable string quartets commissioned by Prince Andrey Kirillovich Rasumofsky from Ludwig van Beethoven gave the Russian art patron’s name an enduring fame. Visitors, moving close enough to the watercolors to savor details in the furniture, floors and fabrics, noticed that Alt had included Kriehuber’s framed portrait of Alois II and his young daughter in two of his three pictures of the Rasumofsky palace drawing rooms (figs. 6, 7).

On the adjacent wall hung three equally charming exterior views of the palace and grounds by Joseph Höger (1801–77): the neo-classical building set in an English-style garden, a vista from its terrace, and another from a garden pavilion (fig. 8). The prince appointed Höger as drawing master to his children, and sometimes invited the artist to accompany him on his trips. In 1818, nearly a century after the founding of the Principality, the twenty-two-year-old Alois II traveled to Liechtenstein. More curious than his predecessors, in 1842 he became the first reigning prince to visit Vaduz, the place to which they owed their princely status.

Complementing landscapes by Rudolf von Alt in the second room of the Albertina show was mountain scenery from the 1830s by Höger. Around 1836 Alois II commissioned from Höger a group of watercolors under the title, “Views from the Salzkammergut.” On display were ten sheets from the series given in 1978 to Prince Franz Josef II (1906–89), father of the current prince, and one sheet he purchased in 1987. The insightful hanging by the curators offered several opportunities to compare works by two artists side by side. The first pairing in the second room was a vertical Höger vista of Lake Gosau Facing the Dachstein, a classical Salzkammergut motif from the 1836 series (sheet 14), hanging to the left of a horizontal view by Alt dated, surprisingly, 1827 (fig. 9). Alt would have been around fifteen when he produced three views in Mödling, a town some fourteen miles south of the city in the Vienna Woods. The sheet, hung next to the Höger, was purchased in 1906—the year following Alt’s death—by his admirer Prince Johann II von Liechtenstein.[8]

The Mödling landscape was the earliest of Alt’s thirty-eight works in the anniversary exhibition. In broad strokes, Alt caught the changing colors in autumn, painting from a rocky streambed in the valley looking up to a Babenberg castle ruin, in a composition that seems at once perfect and unfinished. Although Höger was praised for his depictions of trees, the rocky Lake Gosau shore in the foreground of his watercolor is bleak. The young Alt’s foliage, by contrast, is fluid and masterful, similar to the treatment of the English garden in his view of Lednice (Eisgrub in German) dating from about 1830, before Alois II transformed the Liechtenstein castle in southern Moravia into a neo-Gothic pile. The watercolor of Lednice and its garden was chosen for the catalogue cover (see fig. 2).

This last Alt landscape hung in the second room as part of a group with other images—both interior and exterior—of the Moravian castles Valtice (Feldsberg in German) and Lednice (fig. 10). The Czech Republic denied the Liechtensteins’ application for restitution after World War II, and the properties have been combined in a UNESCO World Heritage Cultural Landscape. Alt’s remarkable interior of the pioneering Lednice Palmenhaus was a highlight of the display (fig. 11). The historic winter garden, dating from the early 1840s, survives in altered form as a reminder of Prince Alois II’s interest and investment in modern English architecture. Alt revealed the barrel-vaulted structure’s cast-iron components, its bamboo-stalk columns with leaf capitals, its small glass panes, along with an exotic bird strutting down the aisle and a magical glimpse of the snowy world outside the hothouse, where fur-muffled visitors approach the entrance.

In the third room, as the wall text announced, the visitor encountered a new intimacy with the princely offspring. Another Kliehuber family portrait—painted three years after the earlier watercolor of Alois II with his barefoot daughter—shows the prince with his wife Princess Franziska and their three oldest daughters. A row of four small portraits of their children by Peter Fendi (1796–1842) followed (fig. 12). Three vignette watercolors carefully dated August 1840 depict five winsome princesses summering at Lednice, and the fourth watercolor, from 1841, captures the future reigning prince, Johann II, in his playpen, one year old and bare-bottomed (fig. 13).

Through his compositional choices and delicate washes, Fendi communicates a natural intimacy with the young royals, as noted by Kräftner in his elegant and lavishly illustrated essay for the exhibition catalogue.[9] The image of the baby prince produced a smile from nearly every viewer, and it may indeed contain a wry curatorial comment. During his seventy-year reign Prince Johann II tried to banish all nudity and violence from the Liechtenstein collections. Still mourned among Prince Johann II’s deaccessions are two Rubens paintings acquired around 1700 by Johann Adam Andreas I: Samson and Delilah (auctioned in 1880 and now in the National Gallery, London) and Massacre of the Innocents (sold in 1921 and now in the Thomson Collection, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto).[10] Two oil paintings by Fendi, described in Rubens to Makart, hung appropriately with the watercolors in the third room (fig. 14). Visit to the Nun was a favorite subject for the artist, and exhibition viewers could compare the oil on panel from 1838 with a watercolor from the following year.[11]

The fourth room in the show was also devoted to Fendi, with ten of his watercolors and two by his pupil Carl Schindler (1821–42); all but one were purchased for the collection after World War II. A vitrine held a Fendi sketchbook, a major acquisition in 1981 by Prince Franz Josef II, who bought four more Fendi works in 1982–83 (fig. 15). His son, Hans-Adam II, would not only continue but escalate the campaign to fill gaps in the Biedermeier holdings massively depleted by Prince Johann II’s donations to the Wien Museum and other public collections from 1894 to 1916.[12] Fendi’s Mouse Hunt (ca. 1834) was one of Prince Hans-Adam II’s acquisitions of 2015 (fig. 16). Another was Hide and Seek (1838; cat. 77), featured on the cover of an auction catalogue in 1924.[13]

The ample space and explanatory wall texts of the fifth room allowed the visitor glimpses of Rudolf von Alt at work abroad under the rubric “Yearning for Distant Places” and at home in “The Changing City” (fig. 17). The generous placing of benches in the show was especially welcome in that penultimate room, where one needed time to reflect between stops on an Italian grand tour and a city walk in Vienna. The hanging presented two more instructive comparisons. The first brought together two works by Jakob Alt and his older son, working not far from one another on the Naples waterfront in 1835. In the catalogue, as in the exhibition, Jakob Alt’s View of the Castel dell’Ovo in Naples on the left made a strong double spread with Rudolf Alt’s At the Port of Santa Lucia in Naples on the right (figs. 18, 19). A second hanging in that fifth room paired Rudolf with his brother Franz in Vienna (fig. 20). In the only work by Franz Alt selected for the anniversary show, acquired in 2016, the artist depicted the palace of his Habsburg patron, Archduke Ludwig Victor, youngest brother of Emperor Franz Joseph. For the foreground of his 1879 watercolor, Franz Alt inserted staffage figures organized in a stately parade (fig. 21). The curators may have chosen Rudolf von Alt’s lively scene in the Hohe Markt, dated 1836, to invite a comparison of the brothers’ use of such figures (fig. 22).

The small sixth and last room of the show was a coda honoring the painter Thomas Ender (1793–1875). Entitled “Alpine Worlds,” the display included only four watercolors and two paintings. One other Ender watercolor, Ice Blocks on the Danube in the Augarten (1831), hung in the second room of the exhibition in a trio of winter landscapes by Höger and Friedrich Gauermann (1807–62). Ender’s delicate view of ice on the bank of the Danube had been acquired by Prince Franz Josef II in 1982, the same year he bought one of the two Ender oil paintings of glaciers in the watercolor show, The Vogelmaier Ochsenkar Kees (1834), displayed in the final room (fig. 23). Ender’s other work on canvas in this room, a prize acquisition by Prince Hans-Adam II in 2015, complements his father’s purchase with a view painted around 1830 of the Pasterze glacier beneath Austria’s highest mountain, the Grossglockner. The glacier is part of the High Tauern National Park, and Alexandra Hanzl, author of the catalogue entry in Rubens to Makart, points out the tiny figures on the ice in both paintings (nos. 92 and 93; fig. 24). She also mentions a grave reminder from the Austrian Alpine Association that as of 2017 eighty-two of the eighty-three glaciers under study show massive loss, and the largest, Pasterze, was judged to be “in a particularly poor state.”[14]

Ender had been appointed in 1817 to join the scientific expedition that delivered Archduchess Leopoldina to Rio de Janeiro to begin her ill-fated marriage to Pedro Braganza, future emperor of Brazil. Nearly eight hundred watercolors Ender made during the expedition are preserved in the print room of the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, where he later became a professor of landscape. As court painter to Archduke Johann, brother of Emperor Francis I of Austria, Ender explored the Alps and promoted the development of Bad Gastein, the spa favored by the archduke for its hot springs.

Showing Fendi’s and Ender’s paintings and watercolors in the Alt exhibition was sensible, although only the oils were described in Rubens to Makart, and only the watercolors listed in Rudolf von Alt und seine Zeit. Similarly, within Rubens to Makart the curators introduced a vitrine of splendid watercolors by Franz Anton von Scheidel (1731–1831) and the Bauer brothers. Checklist entries for these works, as well as a fascinating essay on the scientific illustrators by Stefanie Hoffmann-Gudehus, appeared in the catalogue for the Alt show (164–71). The director of the University of Vienna Botanical Garden and the garden at Schönbrunn, Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin, chose Scheidel to prepare the 500 drawings for the engraved plates in Florae Austriacae (1773–78) and other publications. Scheidel’s watercolors on display in the exhibition came from an album of 100 birds and another album of eighty fishes; Hans-Adam II acquired both in 2007, and a drawing of an armadillo in 2006.

The oldest of the Bauer brothers, Joseph Anton (1756–1831), was fourteen when he and his two younger brothers set to work in Valtice on what became known as the Codex Liechtenstein. After the death of Alois I Josef, Joseph Bauer was promoted in 1806 to the director’s post for the Liechtenstein art collection in the summer palace in Vienna. He was responsible for the installation of the galleries after Johann I decided to move the art collection from the inner city to the Rossau summer palace. The younger Bauer brothers—Franz Andreas (1758–1840) and Ferdinand Lukas (1760–1826)—continued their careers as botanical and zoological illustrators.[15]

Some visitors, descending from the Alpine heights of the sixth gallery and returning to the exit through the fifth room, stopped to photograph or take another look at a large watercolor by Rudolf von Alt. Depicting a view of the stairway of the new Hofoper (now the Staatsoper) in 1873, the year of the world’s fair in Vienna, Alt’s sheet demonstrated that he had moved beyond the Biedermeier era and could reproduce a Gesamtkunstwerk of the Ringstrasse period (fig. 25). In that year, Alt was elected president of the Künstlerhaus, the main artists’ organization, of which he was a founding member. Nearly two decades later, according to rumor and anecdote, a Liechtenstein prince was among the throng arriving in the Skodagasse to congratulate Alt on his eightieth birthday.[16] The artist was not at home. He was at work outdoors on his latest watercolor: Am Hof, a square in the inner city. The sheet, dated August 28, 1892, was purchased for a large sum by the artists’ society and given to the Kunsthistorisches Museum; it is now in the Albertina.

In support of the younger generation, Alt resigned from the Künstlerhaus in 1897 to join the breakaway group led by Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Josef Hoffmann, and others. At age eighty-five, Alt accepted the invitation to become the honorary president of the Vienna Secession. In 1903 at ninety he made from his studio window a watercolor that so impressed the Secessionist artists that they awarded it a laurel wreath when they installed it in their seventeenth exhibition: The Kitschelt Iron Foundry in the Skodagasse in Vienna (acquired by the State and now in the Albertina). Decorated and ennobled, Alt died at age ninety-two in his bedroom in the Skodagasse on March 12, 1905. An allegorical statue by Josef Engelhart (1864–1941) was unveiled on his grave in the honor section of the Central Cemetery in 1908. In October 1912, a few months after what would have been the artist’s hundredth birthday, an over life-size stone monument by Hans Scherpe (1855–1929) was unveiled in the Minoritenplatz near the Hofburg (fig. 26). Alt is appropriately shown at work, outdoors.

Albertina directors have repeatedly demonstrated their admiration for Alt through regular exhibitions. The 2019 show on Rudolf von Alt and his period with its focus on the Liechtenstein holdings invited new insights and comparisons. The exhibition was not only satisfying, but also enlightening in many respects, particularly in the history of taste. Alt is still as famous as Klimt in Vienna, where the omnipresent Manner confectionery logo is based on his watercolor of St. Stephen’s Cathedral. The prolific artist first painted the landmark around 1831 and replicated the view at least a hundred times during his career.

There was no version of the cathedral in the anniversary exhibition, but an Interior of St. Stephen’s (1841) is one of three Rudolf von Alt watercolors in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Austrian visitors to the Albertina show may have looked for the cathedral in vain, yet the path through the six rooms was inviting, the spaces and layout consistently varying according to the content. Constructing a narrative was aided by logical groupings of the approximately ninety works and clear wall texts in German and English. The catalogue designer had an easier task, relying on alternating details and double spreads, and separating the four essays with pictorial sequences. The result is a handsome record of the exhibition.

Three essays for the Alt catalogue have been mentioned briefly so far: those by Johann Kräftner, Anna Hanreich, and Stefanie Hoffmann-Gudehus, all apt and informative. Following a series of reproductions of the watercolors of Liechtenstein dwellings is a trenchant essay by Werner Telesko on other noble families and their art and architectural patronage. He points out the relative austerity of the Habsburgs between the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 and the revolutions of 1848, in contrast to a tendency toward tape à l’œil among the noble families as they positioned themselves in a changing society. After discussing costumes in formal portraits, as well as decorative interiors, Telesko pleads for a more nuanced view of the cliché of Biedermeier simplicity.

The detailed information on acquisition dates in both the Tricentennial catalogues (the checklist for the Alt show and the full individual entries for Rubens to Makart) offered an opportunity to learn more about the Liechtenstein collectors. Many North American visitors recalled that Ginevra de’ Benci (1474–78), the only Leonardo painting in the United States, came to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, in early 1967 because of the financial straits of Prince Franz Josef II. Few exhibition-goers, however, were aware that in the 1980s the prince (or perhaps his son, who acted as his deputy after 1984) was buying Alts, Enders, Fendis, and a Höger.

Collecting Alt, even during his lifetime, had its problems. He was industrious, repeated images as if they were prints and had both imitators and forgers. Among the imitators was Adolf Hitler. After the Anschluss in March 1938, the Führer engaged a team in Munich and in the newly annexed Vienna to acquire Alt watercolors by any means, including outright theft. Many of those works are now lost, and only a few have been restituted to the heirs of their lawful owners. In provenance research the name Alt signals a compelling need for investigation.[17] To the descendants of collectors who lost their beloved watercolors and, in many cases, their lives, such an undertaking is well worth the effort.

In 1938 Franz Josef II began his regency by moving his family to Vaduz, where he ensured that the Principality remained neutral during World War II. The collection followed its owners westwards near the end of the war. Franz Josef II was the first reigning prince to settle permanently in Liechtenstein, a country that has not been occupied by foreign troops since the time of Napoleon, nor has it changed its borders in its three centuries of existence. As this anniversary exhibition clearly shows, Hans-Adam II continues the family tradition of enthusiastic art acquisition and patronage.

Jane Van Nimmen

Independent researcher, Vienna Austria

jvannimmen[at]gmail.com

[1] All works in both parts of the anniversary exhibition can be viewed in chronological order as enlargeable closeups with frames and installation images at https://kunstbeziehung.goldecker.de, accessed September 17, 2019. Click on the title of the exhibitions for direct links: Rubens bis Makart (From Rubens to Makart) and Rudolf von Alt und seine Zeit (Rudolf von Alt and his Time).

[2] Klaus Albrecht Schröder and Johann Kräftner, From Rubens to Makart: Liechtenstein. The Princely Collections, exh. cat. [hereafter, Rubens to Makart] (Vienna/Cologne: Wienand, 2019), 9.

[3] Johann Kräftner, “Liechtenstein: The State, the Family, their Collection and Palaces, Aspects of the History of a European Dynasty,” in Rubens to Makart, 22–23. The name Johann is frequently shortened to Hans.

[4] Anna Hanreich, “Der ‘gefährliche Nebenbuhler’: Zur Beziehung von Fotografie und Malerei im 19. Jahrhundert,” Rudolf von Alt und seine Zeit (“The ‘Dangerous Rival’: The Relationship between Photography and Painting in the 19th Century”), Rudolf von Alt and His Time. 92–103.

[5] For the work of Jakob Alt and his oldest son on a commission from Archduke Ferdinand (later Emperor Ferdinand II of Austria), see Klaus Albrecht Schröder, ed., and Stefanie Chaloupek, Jakob und Rudolf von Alt: Im Auftrag des Kaisers (Jakob and Rudolf von Alt: At His Majesty’s Service), exh. cat. (Wien: Brandstätter, 2010), catalogue of an exhibition held at the Albertina, February 10–May 24, 2010.

[6] Alt’s watercolor interiors remained in demand throughout his long career. Among the most famous was his view of Hans Makart’s Studio in the Gusshausstrasse, made in 1885 before the auction of the studio contents following the famous painter’s death the previous October. Alt’s last watercolor, Das Arbeitszimmer des Künstlers (The Studio of the Artist) (1905, Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München), unfinished at his own death, was one of several he made of his workplace in the Skodagasse.

[7] Alois II also acquired in 1837 the magnificent Portrait of Antonio Canova (Rubens to Makart, cat. no. 73) commissioned by Rasumofsky in 1806 from Johann Baptist Lampi. Lampi depicted the sculptor at work on the monument to Archduchess Marie Christine, the late wife of Prince Albert of Saxony, Duke of Teschen, in the Augustinerkirche, near the Albertina.

[8] The Mödling watercolor on display is cat. no. 34 in Rudolf von Alt und seine Zeit. On Alt’s other Mödling watercolors from 1827, see Walter Koschatzky, Rudolf von Alt mit einer Sammlung von Werken der Malerfamilie Alt der Raiffeisen Zentralbank Österreich AG, zusammengestellt und kommentiert von Walter Koschatzky und Gabriela Koschatzky-Elias (Vienna/Cologne/Weimar: Böhlau, 2001). Concerning his new and expanded version of his 1975 list of watercolors and drawings, Koschatzky (1921–2003), retired director of the Albertina, admits that he could include in his list only some 1,500 of an estimated 5,000 works, see p. 361.

[9] See Johann Kräftner, “Das Wiener Aquarell des Biedermeiers in den Fürstlichen Sammlungen,” Rudolf von Alt und seine Zeit, 13–31. The Liechtenstein holdings include two equestrian oil portraits of Johann II at age five by Friedrich von Amerling. One is more formal, with the boy and his white pony in a regal pose worthy of a Spanish Infante. The appealing sketch, purchased by Prince Johann II himself in 1888, looks more spontaneous, even untamed.

[10] On these and other losses, see Kräftner’s essay in Rubens to Makart (as in note 2), 26.

[11] Another recent acquisition on this wall, Childish Devotion (1842; oil on cardboard), reminded Maria Luise Sternath, author of the catalogue entry in Rubens to Makart (no. 85), of Fendi’s watercolor The Evening Prayer (1839; Albertina, Vienna). There Fendi showed the future Emperor Franz Joseph at age nine kneeling with three younger siblings as their mother, Archduchess Sophie, supervised their prayers.

[12] The generosity of the prince is documented in Johann II. von und zu Liechtenstein: Ein Fürst beschenkt Wien, 1894–1916, Renata Kassel-Mikula, ed., exh. cat. (Vienna, Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien, [2003].

[13] C. G. Boerner, Auktions-Institut, Kunst- und Buch-Antiquariat [Leipzig], eds., Aquarelle Österreichischer Künstler: Sammlung kostbarer Aquarelle zumeist österreichischer Künstler aus fürstlichen Besitz, Versteigerung 24. Mai 1924 (Katalog Nr. 143), cover and no. 45, p. 10.

[14] Rubens to Makart, 221.

[15] Kräftner’s catalogue essay for Rudolf von Alt und seine Zeit also discusses Scheidel and the Bauers (16–18). Kräftner reproduces a watercolor by Rudolf von Alt of the neo-Gothic library at Lednice where the prints and drawings collection was stored until the disruption at the end of World War II, when it was taken to the Rossau palace (18).

[16] Perhaps the visit was from Prince Alfred von und zu Liechtenstein of Hollenegg, who lent thirteen Alt works in 1892 to the jubilee exhibition at the Künstlerhaus: see Koschatzky (2001), 300, 307.

[17] If there is one recent exhibition catalogue that should be read in conjunction with the Liechtenstein Tricentennial show under review, it is Rudolf von Alt: . . . genial, lebhaft, natürlich und wahr: der Münchner Bestand und seine Provenienz, Andreas Strobl, ed., exh. cat. (Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2015). The catalogue accompanied an exhibition mounted by the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München at the Pinakothek der Moderne (July 23–October 11, 2015), with contributions by Meike Hopp and others. The catalogue represents a model for serious provenance research.