The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

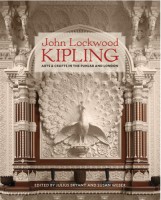

Julius Bryant, Susan Weber, et al.,

John Lockwood Kipling: Arts and Crafts in the Punjab and London.

New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2017.

580 pp.; 700 color and 37 b&w illus.; chronology; bibliography; index.

$75.00 (hardcover)

ISBN: 9780300221596

This comprehensive catalogue highlights an often overlooked chapter of the late nineteenth-century Arts and Crafts movement that embraced the handcraft tradition of the colonial periphery. In this instance, the movement is seen through the work of a man that straddled the roles of governmental official and traditional arts activist. John Lockwood Kipling (1837–1911) has been long overshadowed by the literary fame of his son Rudyard Kipling, born while Kipling senior was employed as the professor of architecture at the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art and Industry in Bombay, modern day Mumbai. Edited by Julius Bryant and Susan Weber, with the support of the Bard Graduate Center and the Victoria & Albert Museum, this catalogue was written in conjunction with the 2017 exhibition of the same name.

Most of the six-hundred-page text is dedicated to seventeen essays written by Julius Bryant, Catherine Arbuthnott, Sandra Kemp, Susan Webber, Peter H. Hoffenberg, Barbara Bryant, Elizabeth James, Nadhra Shahbaz Khan, and Abigail McGowan. The catalogue also contains a useful chronology and checklist for the 2017 exhibition, as well as a selected bibliography and brief author biographies.

Deborah Swallow prefaces the catalogue by acknowledging the problematic, imperialistic nature of John Lockwood Kipling’s position in the British Raj. Referencing the work of postcolonial critics such as Homi Bhabha and Edward Said, Swallow establishes the stakes of dealing with material produced for an imperial audience by subaltern populations, invoking Ardindam Dutta’s ideas about industrial design as a form of imperial control on the Indian subcontinent. This early concession to the history of colonial power allows the authors to carve out space to view the work of Kipling with a nuanced lens. According to the editors, they pursued this project in order to provide a balanced view on an overlooked but influential figure who lived and worked in a period of great political and artistic upheaval. Previously known primarily to postcolonial scholars, Kipling has remained an obscure figure in comparison to his contemporaries E.B. Havell and George Birdwell, not least because his son Rudyard destroyed most of his papers following John Lockwood’s death. This book is the first comprehensive investigation into Kipling, his legacy and the complex reality of the arts produced during the British Raj.

While the text is primarily biographical in character, it does not follow a strict chronological progression, organizing itself instead around thematic elements of Kipling’s artistic and pedagogical practice. This organization allows for reiteration of Kipling’s broad artistic interests which often looped and overlapped each other as he worked to promote the arts as well as provide financially for his family. Kipling’s background as a lower-middle class ceramicist granted him great sympathy and appreciation for the hereditary artisan classes of India. Working in both Bombay (Mumbai) and Lahore, Kipling dedicated more than two decades to the training, perseveration, and promotion of arts of the region with an eye towards producing works which would appeal to the British metropole. The book considers Kipling’s artistic training, decades in India and eventual retirement in England, offering a broad view of his life and influences and placing him in relation to contemporary artistic movements and critics such as John Ruskin and Owen Jones.

The first and second chapters of the book, written by Julius Bryant, provide background on the South Kensington Museum and a biography of John Lockwood Kipling. In Chapter 1 “India in South Kensington, South Kensington in India: Kipling in Context,” Bryant introduces the reader to a who’s who of mid-nineteenth-century British artists, designers, critics, and theorists, deftly placing Kipling within the newly emerging South Kensington curriculum and museum. He briefly sketches out the politics and history of the Sepoy Rebellion and addresses competing ideas from the period on the state of Indian art and what should be done to preserve and promote it. In the following chapter “The Careers and Character of ‘J.L.K.’”, Bryant traces the life of Kipling and attempts to reconstruct his personality for the reader. This is greatly helped by Kipling’s numerous self-portrait sketches, which highlight a humorous, light hearted side.

Christopher Marsden discusses Kipling’s training as a ceramicist and sculptor before leaving for India in 1865 in “Ceramics and Sculpture, Staffordshire and London, 1852–65.” Kipling’s artistic path was unconventional, moving from transferware apprentice in Staffordshire to architectural sculptor in London. According to Marsden, this proved to be useful for Kipling’s career in India. While much of Kipling’s early work cannot be easily attributed to his hand, Marsden provides numerous examples of objects produced during his tenure in each atelier.

Chapters 4 (“Kipling as Sculptor”), 5 (“Kipling and Architecture”), and 6 (“Kipling as Designer”) written by Julius Bryant, address Kipling’s interest in sculpture, architecture, and design. These chapters deal specifically with the work Kipling produced while in India, including public commissions. Bryant demonstrates that Kipling’s Indian work combines a South Kensington style with various Indian motifs. This was also the case with architecture, where Kipling helped collaboratively design multiple buildings in Lahore which looked to local traditions for inspiration. Using primary sources written by Kipling, Bryant traces the development of Kipling’s aesthetics and networks of collaboration with his students and other European designers. It is striking to note the wide range of media employed by Kipling, all with great proficiency.

Catherine Arbuthnott explores one collaborative design project mentioned by Bryant in the following chapter, “Designs for the Imperial Assemblage, 1877.” In 1877 the Mayo school under the direction of Kipling was commissioned to create a visual program for the Imperial Assemblage when Queen Victoria was declared Empress of India. Arbuthnott provides a brief history of the assimilation of the Mughal durbar by the British Raj in order to replicate the traditional monarchical hierarchy. She then describes two of the major projects undertaken by Kipling, the design of heraldic banners and the construction of the official amphitheater. Unlike the work discussed in previous chapters, these were conceived as parts of performances.

Chapters 8, “The Appreciative Eye of a Craftsman: Kipling as Curator and Collector at the Lahore Museum, 1875–93,” and 9, “Kipling and the Exhibitions Movement,” written by Sandra Kemp and Susan Weber respectively deal with Kipling’s collecting and exhibition strategies. Chapter 8 is expansive, covering the history of the Lahore Central Museum, collecting practices, administrative duties, organization, local responses, and international networks. Like the South Kensington Museum, Kipling developed the collection of the Lahore Central Museum as a teaching resource for his students at the Mayo School. The influence of the tenets of the Arts and Crafts movement can be seen in his collection of local art, which he hoped would preserve the tradition from encroaching industrialization. Kemp points to Kipling’s attempts to bridge the gap between the museum and local inhabitants along with his clashes with local administrators as evidence of his more democratic and accepting attitude toward the native population, as compared with most other colonial officers. In Susan Weber’s chapter, she moves Kipling’s influence out of India and onto an international stage with his participation in exhibitions. Starting with a review of the Great Exhibition of 1851, Weber organizes her chapter chronologically, covering the dozens of displays Kipling participated in either as artist, organizer, or critic. These exhibitions often served the function of promoting the commercial aspects of art produced by students at the Mayo school.

Peter H. Hoffenberg’s Chapter 10, entitled “Kipling as Conservationist: The Journal of Indian Art and Industry,” focuses on Kipling’s writings for the Journal of Indian Art and Industry, which promoted Indian arts in London. The journal was founded and edited by Kipling in 1884 almost a decade after moving to Lahore, and fulfilled Kipling’s ambitions to elevate the status of Indian art. Hoffenberg traces the various authors of The Journal, including Kipling’s rival Birdwood, to demonstrate the wide range of responses to Indian art by specialists, administrators, and civil servants. It also vacillated between a discussion of aesthetics and promotion of local industry similar to the international exhibitions. Hoffenberg concludes his chapter by discussing the positioning of Kipling within the Arts and Crafts movement using The Journal of Indian Art as his political vehicle for the promotion of handcraft works and artisans.

Chapter 11, “My Bread and Butter: Kipling’s Journalism,” written by Sandra Kemp, looks at Kipling’s ample output as a journalist. Kemp organizes the chapter around the many different types of journalism undertaken by Kipling, who seems to have often been motivated by financial necessity. He produced opinion columns, governmental critiques, current events, and descriptive scenes. Kemp’s article shows a very different side to Kipling. Writing for Anglo-Indian papers, his work more closely aligns with the stereotypes found in his son’s fiction. Yet, Kemp highlights the complexity of Kipling by pointing to his exposés on the conditions of prison carpet weavers.

Barbara Bryant and Sandra Kemp each dedicate a chapter on Kipling’s family, an unusual inclusion for a monograph, but very welcome in this instance. Bryant’s Chapter 14, “Alice Kipling: Pre-Raphaelite Sister of the Raj,” delves into the history of Kipling’s wife Alice, one of the four famous daughters of Wesleyan minister George Browne Macdonald. Organized as a traditional biography, the author describes Alice as a Pre-Raphaelite muse in the circle of William Morris and her bother-in-law Edward Burne-Jones before her marriage to Kipling. The following chapters are grouped chronologically and geographically as she moved back and from England to India over the following decades. Her accomplishments as a poet and writer are emphasized as well as her role as matriarch of the family.

Elizabeth James’s chapter explores Kipling’s work as an illustrator in Chapter 13. Unlike his career as a journalist, Kipling continued to pursue his artistic interests following his return to England, illustrating particularly his son’s books, which suggests that he derived special pleasure from this type of work. The author has organized Kipling’s work into four major categories; Indian books, books about India, illustrations of fiction and myths, and sculpture and photography. James highlights how each of these four categories was developed for a different audience, evidence of Kipling’s wide, artistic range.

Kemp’s final chapter focuses on collaborative projects of John Lockwood Kipling and Rudyard Kipling. Again, organized chronologically, Kemp explores the influence of John Lockwood on his son Rudyard’s highly visual writing style. Kemp includes numerous sketches made by Rudyard Kipling displaying his proclivity towards caricature representation like his father.

Julius Bryant highlights Kipling’s large, architectural commissions in late-nineteenth-century England in “Kipling’s Royal Commissions: Bagshot Park and Osborne.” Bryant meticulously reconstructs the timeline of the commissions through correspondence and journals, preserved by the royal family. It is apparent that Kipling oversaw much of the detail regarding the construction and aesthetic decisions of the spaces—a billiards room in Bagshot Park and the Durbar Hall in Osborne—yet delegated much of the work to his assistant Bhai Ram Singh. Singh had also been Kipling’s partner on the construction of many of the architecture projects in Lahore, suggesting Kipling felt a high level of confidence and wished to publicly demonstrate the skills of a traditional craftsman.

Nadhra Shahbaz Khan writes on Kipling’s work to establish the Mayo School in Lahore as well as the artisans in the region. She opens by briefly traces the history of Lahore and its native art traditions based on hereditary artisan families and royal patronage. In this chapter Khan highlights the various methods Kipling employed to preserve and promote the arts of Lahore such as the broad curriculum of the Mayo School, translation of textbooks, and relying on established traditional artisans to provide expertise. Khan references official documents of the Mayo school such as the annual reports and syllabus as evidence. Even after Kipling’s retirement, his influence was maintained in the school according to the subsequent reports.

Finally, Abigail McGowan investigates how Kipling continued to influence the pedagogy of the arts of India into the twentieth century. McGowan opens by acknowledging the conflicting stance scholars take on Kipling’s role as colonial agent but sets this inquiry aside in favor of investigating Kipling’s influence in the decades following his retirement. In her chapter she explores how traditional artisans continue to struggle to provide subsistence livings but are supported by various groups who are ideological descendants of John Lockwood Kipling.

Tracing Kipling’s own training as an artist and designer to his work to preserve the crafts of India in the face industrialization, the authors present a complex picture of a man who operated as both a staunch imperialist as well as an advocate for the preservation of traditional art forms. Bryant and Weber call Kipling a “Renaissance man of the Arts and Crafts Movement” in the opening line of the Introduction (viii), and the scope of Kipling as artist, curator, teacher, activist, and administrator becomes clear through the progression of this comprehensive book.

John Lockwood Kipling: Arts and Crafts in the Punjab and London is an encyclopedic and exhaustive look at Kipling. The authors are meticulous in compiling and reconstructing Kipling’s activities and this large text is evidence of the volume of research invested into the project. The authors expand on previous research done by Mahrukh Tarapor, Mildred Archer, Pratha Mitter, Arindam Dutta, and Arthur Hoffenberg most of which was completed thirty to forty years ago. Richly illustrated and well-researched, this catalogue allows for a multifaceted view on a figure who has been unjustly overlooked and overshadowed during the past century.

Kirstin Gotway

PhD student, Art History

School of Art + Design

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

kgotway2[at]illinois.edu