The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

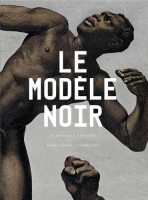

Le Modèle noir de Géricault à Matisse

Musée D’Orsay, Paris

March 26–July 21, 2019

ACTe Memorial, Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe

September 13–December 19, 2019

Catalogue:

Le Modèle noir de Gericault à Matisse.

Paris: Musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie and Flammarion, 2019.

384 pp.; 274 color illus.; bibliography; index.

$47 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-2-35433-281-5

ISBN: 978-2-0814-8096-4

In the heat of the racially charged American political climate of the 1960s, the French-American collectors and patrons Jean and Dominique de Menil embarked on The Image of the Black in Western Art project, a monumental effort to document all of the images of blacks in Western art. The de Menils believed that dignified, beautiful representations of black men, women, and children emanating from the ancient Mediterranean to modern Europe would serve as a counternarrative to the toxic atmosphere of race relations they witnessed while living in the United States. They believed in the redemptive power of the image. Their project resulted in an archive of photos and a magisterial series of books by multiple authors that attempted not only to document but to build a scholarly field chronicling the black body as a shifting, evolving, and complex symbol. The sheer number of images proved that the black figure was essential to Western iconography, but the motif had nonetheless been largely ignored by dominant Eurocentric narratives of art history. Hugh Honour’s astute, eloquent treatment of the nineteenth century in volume V of the original series offered a rich, expansive view of images of black people in European and American art.[1] The introduction of this archive of images, the reissue of the original volumes, beginning in 2010, and the addition of new volumes has nurtured a global field of inquiry that continues to capture the imagination of scholars, students, artists, writers, filmmakers, and curators. In many ways, the blockbuster exhibition Le Modèle noir de Géricault à Matisse (The Black Model from Géricault to Matisse), mounted by the Musée d’Orsay (fig. 1), might be considered an extension of this project. Much like the de Menils’ The Image of the Black in Western Art project, Le Modèle noir is a collaboration by an international group of stakeholders, including curators, scholars, and institutions. This contemporary alliance reflects black Atlantic histories that connect Africa, Europe, and the Americas and inform the fascinating works presented in Le Modèle noir.

Le Modèle noir de Géricault à Matisse was organized by the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée de l’Orangerie, both in Paris, and the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University, New York. Its curators include Denise Murrell from the Wallach Art Gallery, Cécile Debray from the Musée de l’Orangerie, Stéphane Guégan from the Musée de l’Orangerie and the Musée d’Orsay, and Isolde Pludermacher from the Musée d’Orsay. Le Modèle noir is an expanded version of the exhibition Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today, mounted at the Wallach Art Gallery from October 24, 2018 to February 10, 2019, and curated by Murrell. Unlike Le Modèle noir, which spans the “long” nineteenth century into the later twentieth century, Posing Modernity began its inquiry into the black model in French art and visual culture in the 1860s, taking as its critical launching point Edouard Manet’s images of the black Parisian model Laure, who is most famous for her highly charged supporting role in Olympia (1863). Murrell examined the different ways in which Laure figured modernity in Manet’s depictions of her as well as in post-abolition Paris. From there Murrell chronicled Manet’s legacy, as it was embodied in other black female models and the increasingly popular depictions of black women in Paris during the second half of the nineteenth century. Murrell also included transatlantic relationships and featured images of black women by Harlem Renaissance artists, ultimately concluding with contemporary global practice by artists that continues to interrogate and adjudicate the fraught image of the black female in European modernist art. Posing Modernity and indeed Le Modèle noir are passion projects for Murrell, who wrote her 2013 doctoral dissertation at Columbia University on the material that formed the core of Posing Modernity. That the Musée d’Orsay, a venerable, conservative, and historic French institution, would take up an exhibition project by a newly minted curator from the United States speaks to the power and timeliness of the subject matter and the necessity of the institution to consider the black presence in French art in a sustained and serious manner.

Exhibitions and scholarship that mine European imagery of the past featuring black figures have had a long and successful track record. These critical engagements not only have analyzed the significance of the black figure as a symbol but also have illuminated the way in which art reflects, negotiates, and shapes social and historical issues such as slavery, colonialism, racism, and the public presence of exceptional black individuals. Recent notable exhibitions have included Black Victorians: Black People in British Art 1800–1900 (Manchester Art Gallery and Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, Manchester and Birmingham, 2005–06); Black is Beautiful: Rubens to Dumas (De Nieuwe Kerk, Amsterdam, 2008); Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe (the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland, 2012); The Black Figure in the European Imaginary (Cornell Fine Arts Museum, Winter Park, Florida, 2017); and Histórias Afro-Atlânticas (Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, São Paulo, Brazil, 2018). The lack of participation in this dialogue by French museums has been a glaring absence, until now. The irony of this is that nineteenth-century French art features extraordinarily compelling and complex images of black people, especially when held up against American works of the period. Additionally, French painters and academics were highly influential in spreading the taste for the black body in art across Europe and to the Americas. Given the centrality of French visual culture in the construction of aesthetic blackness in Western art, it was clearly time for a major French institution such as the Musée d’Orsay to join this ongoing conversation and take up the challenge of critically reflecting on French traditions of race and representation.

The sheer number of important works featuring black figures represented in Le Modèle noir is nothing less than astonishing. Perhaps only the Musée d’Orsay can assemble such a rich trove combining its borrowing power with a large number of seminal works from its permanent collection. Le Modèle noir is vast, presenting over 300 objects, including painting, sculpture, photography, video, literature, and ephemera. To manage and to bring focus to this panoply of objects, the curators divided the material into twelve distinct sections or micro-exhibitions that take on specific themes and subthemes. Le Modèle noir begins with “New Perspectives,” which puts the issue of slavery at the forefront of the exhibition, and it ends with “I like Olympia in Black,” a glance at twentieth-century artists who have responded to Olympia or to the canvas’s influential construction of race and sex. In between the first and last sections, the exhibition casts a wide net, moving well beyond the “black model” of the title to consider ethnography, art against slavery, mixed-race literary figures, clowns, entertainers, soldiers, prostitution, advertising, colonialism, negritude, Harlem, and more. Historical timelines are interspersed throughout the exhibition, marking milestones in “black history” and the achievements of black personalities. While the wealth of material contributes to the richness of the experience, their disparateness renders it occasionally disjointed, and it is impossible to consume in one visit.

The introductory panel of the exhibition notes that the curators conceived of the “model” broadly, not simply as the artist’s model, but also as exemplary black figures in history, or role models, if you will. The introduction to the exhibition catalogue, authored by all four curators, further explains that the goal of the exhibition is to uncover the lived experiences and identities of the different “models” and to dignify the stories of people who are often caricatured. A tall order indeed. The move to include historical figures and events serves to provide important contextualization that is often needed so that black people in European art are not presented in a vacuum. At times, however, as when delving into the lives and images of famous, and admittedly fascinating, figures like the mixed-race author Alexandre Dumas or the clown Chocolat, the inclusion of such figures feels like a detour.

In the exhibition catalogue Anne Higonnet writes about the bold decision of the exhibition team to rename works of art that refer to people of African descent in pejorative racial terms such as “Nègre” or “Négresse.” Higonnet writes “To better understand the inequity of this selective naming, let us imagine for a moment that a systematic reference to race is indicated in the titles of works. So we would speak of The Young White Girl with the Pearl Earring. And what if we replaced La Joconde with Portrait of a White Girl?”[2] This intervention is a step toward reckoning with the traces of France’s colonial past that are woven through many of the works of art and other materials in the exhibition.

Perhaps the most striking instance of the renaming project undertaken by the exhibition is the newly named Portrait de Madeline (Portrait of Madeline) (1800) by Marie Guillemine Benoist, formerly known as Portrait d’une femme noire (Portrait of a Black Woman) and originally presented in the Salon of 1800 as Portrait d’une Négresse (Portrait of a “Negress”) (fig. 2). The subject, Madeline, was a Guadeloupean servant of the artist’s sister-in-law who, while visiting in Paris, sat for this portrait by Benoist. Portrait de Madeline is an elegant symbol of revolutionary freedom, abolition, and citizenship handled with singular dignity. Ironically, Portrait de Madeline presents a woman who was likely born into slavery but is fashioned to suggest freedom. The painting embodies the contradictions inherent in many of the works of this period, which depict individualistic, elegant, and compelling images of black people but reduce them to types. These “Nègres” and “Négresses” materialize ahistorically in canvases with no indication of how they fit into the artistic and social milieu in which they operated. By focusing on the black models, as opposed to the artists or the larger narratives, Le Modèle noir shifts the entry point into the works and offers another prism through which to examine many beloved objects that we thought we understood.

While Madeline’s identity is a fairly recent discovery, the model Joseph (also referred to as Joseph le Nègre) became a well-known, even celebrated model in his time. We have come to know him through his muscular back, which appears at the apex of Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1819), immortalized in his Étude de dos (d’après le modèle Joseph) pour le “Radeau de La Méduse” (1818–19) [Study of the Back (after the model Model Joseph) for the Raft of the Medusa; fig. 3]. A section of the exhibition is devoted entirely to images of Joseph by artists such as Géricault (fig. 4), Horace Vernet, and Théodore Chassériau (fig. 5). Chassériau’s Étude d’aprés le modèle Joseph (Study of the Model Joseph), executed for an unrealized mural, is featured on the cover of the exhibition catalogue, albeit with the color altered. Chassériau depicts Joseph’s nude body careening from a cliff into an expansive blue sky. Joseph was known for his fit physique and, in fact, many of the exhibited images of Joseph highlight his muscular form nude or seminude and suggest the trope of the eroticized black body, ubiquitous during the period.

Object labels that indicate how titles have changed over the years help audiences to understand the vagaries of naming and point to their political implications. For instance, the label for Eugène Delacroix’s Portrait d’une femme au turban bleu (Portrait of a Woman in a Blue Turban) (1827–28) states that it was formerly known as Tête d’étude d’une Indienne (Study of the Head of an Indian Woman), Une tête de femme mulâtre (A Mulatto Woman’s Head), and Aline la Mulâtresse (Aline the Mulattress). These shifts demonstrate the mutability of the idea of race in general and of the woman of color in particular, who could transform from an Indian to a “mulâtresse,” to a named individual, and eventually back to an anonymous woman in a blue turban.

As the opening panel makes clear, the exhibition develops a variety of themes that extend well beyond the artist’s model. The issue of slavery underpinned the very presence of black people in nineteenth-century France and is taken up in various ways. François-Auguste Biard’s L’Abolition de l’esclavage dans les colonies français le 27 avril 1848 (The Abolition of Slavery in the French Colonies, April 27, 1848) and Marcel Antoine Verdier’s Le Châtiment des quatre piquets dans les colonies (The Punishment of Four Stakes in the Colonies) (1843), both multifigure compositions, feature anonymous models, even romanticized types, but present themes sympathetic to the horrors of the institution and the celebration of its final demise in France. Issues of slavery, freedom, and black identity in France are explored through deep dives into images of exceptional individuals whose lives were impacted by slavery. Toussaint Louverture, the Haitian revolutionary general, and Dumas, the celebrated French writer, who was the son of a mixed-race general in Napoleon’s army and an enslaved Haitian woman, provide opportunities to talk about the Haitian Revolution and its ripple effects in French culture. A display of dignified portraits, as well as racist caricatures of the literary giant Dumas with exaggerated features, reveals the prejudices and resentments that continued to animate the French reactions to blackness through the nineteenth century. There is even an extensive display of literature related to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was translated into French in 1852, bringing to bear the literary context of the issue of slavery. Perhaps the most surprising to me was Jeune Noir à l’épée (Young Black with a Sword) (1848–49; fig. 6) by Pierre Puvis de Chavanne, created after the final abolition of slavery in France in 1848. The enigmatic painting of a nude black adolescent, wearing a red Phrygian hat and holding a sword, seems to be an allegory of revolution or freedom (much like Benoist’s Portrait de Madeline) and fetishizes the black male body. Slavery and freedom in French art and visual culture are immense subjects that could and should consume an entire exhibition.

Félix Nadar’s photographs of notable black individuals offer a view into the lived experiences of black people that is very different from that of artist’s models. We encounter compelling photographs of the writer Victor Cochinat, the equestrienne Selika Lazevski, and Maria l’Antillaise (fig. 7), whom the curators suggest could be the Cuban musician Maria Martinez, popular in the Parisian music scene in the 1850s. While they are still mediated representations, the medium’s indexicality imbues the images with a more intimate and personal connection to the sitter portrayed. In the case of Maria, photography also allowed for slippage from portrait to pseudo-ethnographic documentation, as Nadar poses her in profile and with bare breasts, two conventions that smack of scientific racism and colonialist constructions of black peoples. However, the extent to which black people like Maria were visible and successful in Paris, the capital of the nineteenth century, will likely be a revelation to visitors. In Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today, the companion book to the exhibition of the same name, Murrell points out that Nadar photographed many black Parisians in the 1860s and captured a wider range of social positions and possibilities for blackness than we find in the limited tropes of Salon painting.[3] Yet, the recovery of so many images of black Parisians is a bittersweet revelation: the discoveries are exciting, but they also testify about the amount of material about black lives that has been lost.

As the exhibition progresses chronologically, it moves back into the artist’s studio to explore images of unknown black models in academic painting. The vogue for Orientalism proved fertile ground for the depictions of African bodies in nineteenth-century France, and Jean Léon Gérôme was the standard-bearer. Gérôme’s A Vendre (For Sale) (1873) is exhibited alongside his study of the black model (fig. 8). Gérôme takes care to depict his black models with individuality and distinctive characteristics, which he does not always afford his white figures. This canvas, which depicts two women who are for sale, demonstrates the degree to which Gérôme equates the black figure with chattel slavery (she wears a slave ring around her neck) and the degenerative nature of blackness (she is accompanied by a monkey who mirrors her posture).[4] However, the object label falls short of making that obvious connection. The section includes some less successful images of black models by lesser known or anonymous artists. Although it is illuminating to see how many different Salon artists looked to the black body as a subject, the uneven quality of the paintings did not serve the larger effort.

A pivotal moment for the exhibition is the gallery dedicated to Manet’s Olympia (1863; fig. 9), which includes both earlier and later paintings that likewise depict sexualized white women accompanied by black attendants, servants, or slaves. In this company, the model Laure and her compatriots take center stage. It is thrilling to see Chassériau’s La Toilette d’Esther (Esther’s Toilette) (1841) and François-Léon Benouville’s Esther (1844) both Orientalist precursors to Olympia, along with responses such as Gérôme’s Bain Maure (Moorish Bath) (1870), Frederic Bazille’s La Toilette (The Toilette) (1870; fig. 10), and Paul Cézanne’s Une moderne Olympia (A Modern Olympia) (1873–74) in the same space. It brings home the point that this combination of race and sex traded on fantasies of exoticism that had already informed generations of artists. As conventional as the subject was, in the hands of modernist artists such as Manet, Cézanne, and Bazille, its combination of race and sex reemerged as a hallmark of modernity.

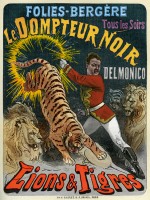

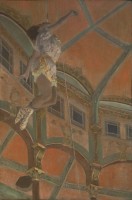

Issues of modernism and aspects of the black experience in modern Paris make up the final leg of the exhibition. Again, small sections are dedicated to various individuals, ideas, or contexts. Perhaps the most far afield are explorations of circus clowns and lion tamers (fig. 11). By this stage in the exhibition, its two tracks have clearly emerged: the “fine art” track that traces the traditional artist’s model through painting, sculpture, photographs, and archival material, and a second track that documents aspects of the lived experiences of mostly celebrated black people in France, from soldiers and acrobats to writers and boxers, through popular imagery, advertising, literature, ephemera, and film. There is crossover, as some artist’s models were also performers, who frequently landed in Paris with traveling spectacles popular with nineteenth-century audiences. Edgar Degas’s Miss La La au cirque Fernando (Miss La La at Fernando’s Circus) (1879; fig. 12) depicts the mixed-race acrobat Olga Albertina Brown. We encounter Miss La La from below at an oblique angle as she ascends to the ceiling via a rope gripped in her teeth. This work is at the intersection of the world of spectacle and the world of art, whose boundaries Degas often traversed.

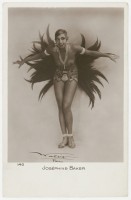

Josephine Baker took center stage as a hallmark of modernity (fig. 13). The iconic expatriate African American entertainer was the doyenne of Jazz Age Paris and in her early years as a cabaret performer came to represent, consciously or not, many of the conceptions about black people as primitive and erotic that were established long before she arrived. Among the Baker memorabilia are photographs, drawings, advertisements, a doll, and a figurine of the entertainer in a banana skirt by Dorthea Charol for Rosenthal Porcelain. A film loop of Baker in a feathered skirt, dancing topless at the Folies Bergère, emphasizes her sexuality and is laced with her signature humor. Yet seeing her shaking her breasts endlessly in the gallery also reinforces the stereotype of the hypersexualized black woman that the exhibition is attempting to complicate.

Some of the most fascinating revelations about black models in the exhibition emerge in the context of early twentieth-century modernist practice. Avant-garde artists such as Man Ray and Pablo Picasso famously engaged blackness and/or Africanness in their search for new forms of modern expression. New scholarship about the Guadeloupean model and dancer Adrienne Fidelin, muse to the surrealist artist Man Ray, has uncovered her centrality as both model and romantic partner to his practice. She was also a member of his inner circle of friends, which included artists such as Picasso, Dora Maar, and Lee Miller. In an essay in the exhibition catalogue, Wendy A. Grossman and Sala E. Patterson reveal that Fidelin was the heretofore unidentified sitter for Picasso’s 1937 portrait Femme assise sur fond jaune et rose II (Woman Seated on a Yellow and Pink Background II) (private collection).[5] This revelation is potentially explosive, as Picasso, known for his interest in the formal and spiritual aspects of African art, rarely, if ever, painted a black model from life. His preference for the African object over the African body is seen by some as an erasure of black voices in the making of modernism.[6] The association between Fidelin and Picasso in the form of Femme assise uncovers new possibilities for our queries into the black female impact on and participation in European avant-garde practice.

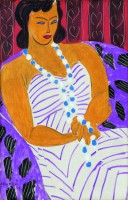

Henri Matisse was perhaps the most engaged with the black body among all of his School of Paris compatriots, as is suggested by such early works as the sculpture Deux Négresses (1908), the racially inflected Blue Nude (1907), and the paintings of the Moroccan woman Fatima the “mulâtresse,” and such late works as the 1953 cutout collage La Négresse. The exhibition and publications associated with it establish that Matisse demonstrated a keen and sustained interest in both African art and black people as subjects. But until this project, there has not been an extended study of Matisse’s images of black figures across his varied media. Le Modèle noir includes the painting Aïcha et Lorette (1917), featuring the celebrated black model and bon vivant Aïcha Goblet. I was surprised by Dame à la robe blanche (Lady with the White Dress) (1946) (fig. 14) as I never understood this painting to depict a black model. The model was Elvire Van Hyfte, a mixed-race friend and frequent visitor to Matisse’s studio in Nice.[7] Interestingly, even though Matisse interacted with black models and subjects throughout his career, he employed the racial marker of skin tone equivocally, making it difficult to establish racial difference, by employing non-natural coloration that generally reads as “white.”

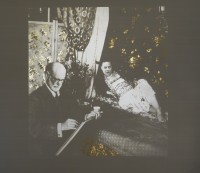

While color may not reveal race in Matisse’s paintings, his elegant line drawings, studies, and prints for the 1947 version of Charles Baudelaire’s Les fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil) unquestionably depict the facial features of black women. The Haitian performer Antoinette Carmen Lahens modeled for many of them. The illustrations were not exhibited with most of the Matisse material, but in an earlier section entitled “Mixed Race in Literature” that features mostly nineteenth-century works. At the very end of the exhibition several photographs of Matisse sketching Carmen in his studio provide a fascinating glimpse into this intimate exchange between artist and model. Unfortunately, this rich assembly of material from photographs of studio sessions to drawings, studies, and the finished products were dispersed through the exhibition, rather than gathered together in a critical mass.

Le Modèle noir concludes with a brief foray into the negritude movement in France and the Harlem Renaissance, spotlighting the voices of black writers and artists. This nod to self-representation includes African American artists such as William H. Johnson and Romare Bearden, who both respond to the modern reclining nude and the lineage of Manet’s Olympia in their depictions of nude black women. The final works include the 1970 riff on Olympia by American artist Larry Rivers, I Like Olympia in Black Face and Olympia II (2013) by Congolese artist Aimé Mpane (fig. 15). Here the curators bring in responses to Olympia that use direct quotations and inversions to question the constructs of race and sex that the original and its predecessors and progeny have naturalized in the guise of tradition, exoticism, or modernity.

Capping off the exhibition, as a bookend to Benoist’s Portrait de Madeline, is Ellen Gallagher’s Odalisque (Self-Portrait with Freud as Matisse) (2013; fig. 16). The large photographic projection offers an irreverent intervention into the artist/model/muse mythology surrounding Matisse, and indeed all of the male European artists in the exhibition. Gallagher, the only black female artist represented in the exhibition, repurposes a vintage photograph of Matisse in his studio and replaces the model’s face with her own and Matisse’s head with Freud’s. Her cutting, sideways glance undermines the authority of the genius artist and mounts a resistance to the trope of the submissive female model, the stock in trade of Matisse’s Orientalism. While Gallagher’s witty repartee with Matisse provided a pithy end point to the exhibition, it was disappointing to see that there were no contemporary black French artists in the exhibition. Have they not responded to the scepter of art history in the same way that Americans and others in the African diaspora have? This is a question I cannot answer, but I would be interested in exploring further.

Anyone paying attention to the contemporary art world has noted the surge of interest in the work of black artists across the globe. Many of these artists take up social concerns of racial inequities in a manner that reflects the de Menils’ notion that art has political power. In a move that brings the current boom of activist art to the core concepts of the exhibition, the Musée d’Orsay commissioned the luminary African American artist Glenn Ligon to produce a work for Le Modèle noir. He created the site-specific installation Some Black Parisians (fig. 17), a work that gets right at the heart of the exhibition—the reclamation and celebration of black identities once obscured. Ligon is a conceptual artist whose text-based works pointedly engage the racial, social, and political inequities that have faced blacks in United States culture. Works such as Untitled (I Am a Man) (1988), foreground the idea that claiming yourself is a step toward being seen as human. In Some Black Parisians Ligon claims and names twelve of the black models and personalities featured in Le Modèle noir. Ligon forms the model’s signatures out of neon lights. Some signatures are fashioned after originals recovered by exhibition research. Treated as headliners, models’ names are emblazoned on the two towers at the end of the museum’s central nave, shining over galleries that once presented them as nameless types. The glamour of the lights is tempered by the intimacy of the personalized signature, reminding us that Miss La La, Laure, Joseph, and Aïcha Goblet were indeed human.

The 384-page exhibition catalogue for Le Modèle noir de Géricault à Matisse is a tremendous resource with hundreds of lavish illustrations and important texts. The large volume features twenty contributors who fashion thirty distinct essays and extended entries on works of art, models, and historical themes. There is no single overarching catalogue essay. Short to medium length offerings provide focused treatments that help to navigate the varied themes. The catalogue covers much of the material in the exhibition, but expands the scope even further going back to the seventeenth century to consider works that are in many ways foundational to the works in the exhibition. New scholarship about models such as Madeline, Joseph, Adrienne Fidelin, Maria d’Antillaise, and Antoinette Carmen Lahens is perhaps the freshest contribution and makes for interesting reading. Some essays dive a bit deeper into the larger themes of the exhibition such as the “Black Atlantic” and black women in the work of Matisse. Four illustrated chronologies that, like the exhibition, cover a wide range of topics dating from 1788 to 1953 focus largely on “black history” in France. For instance, 1848–70 includes important historical moments such as the abolition of slavery in 1848, art-related events such as Charles Cordier’s mission to Algeria in 1856 to study the indigenous races, and cultural events such as the opening of the opera l’Africaine by Giacomo Meyerbeer in 1865. The chronologies provide snapshots of black lives and reveal flashes of creativity around issues and ideas of blackness.

The organizers’ ambition to extend the purview of the exhibition to black personalities and “black experiences” at times distracts from the focus on the artist’s model, which I consider the more cohesive and original thread. Yet, as a whole, Le Modèle noir is gratifying, delivering what it promises and more. It takes the work of a stellar international team of scholars and curators to begin the monumental task of recovering vestiges of the lived experiences of black people and uncover the interplay and exchanges among black and white individuals in the Parisian art world of the “long” nineteenth century, an aspect of art history that has truly been hidden in plain sight. Le Modèle noir de Géricault à Matisse is a groundbreaking and at times stunning exhibition that will make an indelible mark on the history of French art and visual culture. Indeed, the exhibition and its catalogue will continue to inspire creative and scholarly responses and most certainly will have a global impact for years to come.

Adrienne L. Childs

Associate, The Hutchins Center for African and African American Research

Harvard University

Achilds[at]fas.harvard.edu

[1] David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., eds., The Image of the Black in Western Art, vol. 1–5.2, (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010–2014).

[2] Anne Higonnet, “Reonmer L’Oeuvre,” in Le Modèle Noir de Géricault à Matisse, (Paris: Musée d’Orsay, 2019), 27. Original French: “Pour bien comprendre l’iniquité de ce marquage sélectif, imaginons un instant qu’une référence systématique à la race soit indiquée dans les titres d’oeuvres. Ainsi parlerait-on de La Jeune Fille blanche à la perle, de Vermeer. Et si on remplaçait La Joconde par Portrait d’une femme blanche?” Translation by the author.

[3] Denise Murrell, Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 10.

[4] Adrienne L. Childs, “Exceeding Blackness: African Women in the Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme,” in Blacks and Blackness in European Art of the Long Nineteenth Century, ed. Adrienne L. Childs and Susan H. Libby (Burlington: Ashgate; London and New York; Routledge, 2016), 125–45.

[5] Wendy A. Grossman and Sala E. Patterson, “Adrienne Fidelin,” in Le Modèle Noir, 306–8.

[6] See Simon Gikandi, “Picasso, Africa, and the Schemata of Difference,” Modernism/modernity 10 (September 2003): 455–80.

[7] Murell, Posing Modernity, 180.