The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Parabola of Pre-Raphaelitism: Turner, Ruskin, Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Morris

March 14–June 9, 2019

Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum, Tokyo

June 20–September 8, 2019

Kurume City Art Museum, Kurume

October 5–December 15, 2019

Abeno Harukas Art Museum, Osaka

Catalogue:

Christopher Newall, Joichiro Kawamura, Akiko Kato, Namiko Sasaki,

Parabola of Pre-Raphaelitism, Turner, Ruskin, Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Morris.

Tokyo: Artis Inc., 2019.

233 pp.; 152 color illus.; no bibliography; no index; bilingual (Japanese-English).

2,300 JPY (18.7 EUR)

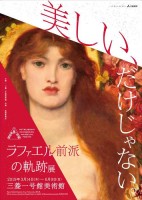

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood assembled in 1848 and dissolved in 1850, yet the rich visual universe its members created exceeded this short time period. Parabola of Pre-Raphaelitism, an exhibition of around 150 artworks currently travelling through Japan, attempts to showcase this larger heritage. Part of a now long-standing history of exhibitions on British art in Japan, this is the third show dedicated to British art at the Mitsubishi Ichigokan after Edward Burne-Jones in 2012 and Art for Art’s Sake in 2014.[1] Flaunting a sensuous female figure from Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Venus Verticordia (1863–68)—an icon of Pre-Raphaelitism—the poster of the show is somewhat misleading: as suggested by its subtitle, the exhibition is not dedicated solely to the movement but includes a range of famous artists of the second half of the nineteenth century. According to standard dictionary definitions, a “parabola” is a “curve, esp. one described by something moving through time or space; a curving trajectory, an arc.”[2] However, what gives the exhibition its particular shape is not as clearly delineated; it is only by moving through the different rooms that the show’s argument subtly and powerfully emerges. Displaying artworks from the 1830s to the 1910s, it is structured around five roughly chronological sections, each focused on separate artists or groups of artists: Ruskin and Turner, The Pre-Raphaelites, Pre-Raphaelite Friends and Associates, Burne-Jones, and William Morris and the Decorative Arts. At the Mitsubishi Ichigokan, a red brick and concrete reconstruction completed in 2010 and based on a previous edifice designed in 1894 by the British architect Josiah Conder, three levels above ground and two below are dedicated to European nineteenth-century art. Originally the first Western-style building in the Tokyo Marunouchi district, the place remains a European antenna in the city. During my visit, a booth welcomed donations for rebuilding Notre Dame de Paris. Despite its strong holdings, there is no permanent collection on display, which means that most of the gallery space is devoted to the exhibition under review here. The exhibition offers an outsider’s view on British art (despite the fact that two of the curators, Christopher Newall and Stephen Wildman, are British academics) and forges connections between different artists and time periods. As such, it is reminiscent of the de-centered perspective embraced by the 2007 exhibition British Vision in Ghent, Switzerland. Curated by Robert Hoozee, this earlier show sought to identify a unique, if marginalized, artistic tradition in Great Britain, and to single out persistent tendencies.

The exhibition in Japan forms part of the celebrations surrounding the bicentenary of John Ruskin’s birth and begins with a dialogue between his and J.M.W. Turner’s works. In the watercolors Bay of Naples (1817), Ehrenbreisten (1832), and The Brenva Glacier, near Courmayeur (1836), displayed in the first room, Turner meticulously captures the evanescence of light and furnishes a precise account of meteorological conditions. Pictures such as these can be read as paeans to the European natural environment, encapsulated in paint as it was beginning to be altered irrevocably by the effects of the Industrial Revolution. Next to them, his mesmerizing oil painting Calais Sands (1830; fig. 1), where sky and sea merge in a luminous expanse, represents one of his first works from the 1830s to depart from more traditional forms of landscape painting. It epitomizes the type of image that Ruskin would later champion in his defense of Turner. While some critics argued that Turner was drifting from honest depiction, Ruskin contended that he was in fact giving precise representations of the different elements of nature. This ambition resonates in the drawings and watercolors by Ruskin displayed in the next rooms (fig. 2). His minute topographical or architectural drawings produce a material experience of the world. In his writings, he highlighted the ontological process at stake in the apprehension and illustration of these subjects. He was adamant that it was by looking at a simple stone or flower that one could form larger ideas about life and its meaning. In the catalogue essay accompanying the show, Newall reminds us of the importance of “genuine observation” for artists of this period, and this paradigm might be read as the key to the entire exhibition. More than simply retracing the legacy of Pre-Raphaelitism, the show relates the history of the Ruskinian dictum of “truth to nature” and reveals it to be an undercurrent running through British art in the second half of the nineteenth century. The mathematical definition of a “parabola,” as “the intersection of a cone with a plane parallel to its side”[3] enables the figurative representation of this trajectory, as a tendency already present in the work of Turner and other artists of the period not represented in the show (one thinks of John Constable, to cite the most renowned). This tendency reached its peak with Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites, before gradually fading and morphing in the works of second-generation Pre-Raphaelitism, Aestheticism, and the Arts and Crafts Movement.

When Turner died in 1851, few artists could claim as ambitious a vision for landscape as his. The landscapes of the Pre-Raphaelites, the most forward-looking painters of the period, were stylistically antagonistic to those of the previous generation. Characterized by minute details with sharp and clear outlines, the visual acuity of their paintings stood in contrast to the thick layers of paint favored by Turner. Yet Newall also points to the paradoxical continuity that transpires in their very attention to surface quality: “For Ruskin, the seething textures that Turner gave to his watercolors signified the constant movement and transience, as well as the irregularities and variations even within larger forms that might appear consistent. Ruskin carries this particular fondness for the quality of surface forward in his recommendation to younger artists to study all aspects of nature as minutely as possible and to include in their compositions whatever lay before them.”[4]

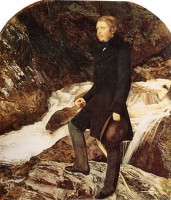

The second section lays out the works of the Pre-Raphaelite painters John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Holman Hunt, its three most famous founding members, as well as those of associated painters such as Ford Madox Brown (who was never formally in the group but closely allied with it), Arthur Hughes, John Brett, Alfred William Hunt, and John William Inchbold. In Millais’ The Waterfall (1853; fig. 3, chosen by the Kurume City Art Museum as the poster image for its show), the sitter, Effie Gray Ruskin, is pushed to the side of the painting, on a bed of rocks occupying two thirds of the canvas. As in other Pre-Raphaelite landscapes, there is almost no horizon here: the beholder is immersed in the geological facts of nature. In their landscapes and portraits, the Pre-Raphaelites sought excruciating accuracy. Through brushwork as well as undiluted colors, they strove to achieve a form of sincerity and truth to nature. The treatment of pigment, often applied on a white background, creates jarring effects, accentuating the flatness of the works and resulting in an equality of focus on the various elements depicted.

Intended as the culmination of the exhibition and located in a vast room (the only one where visitors can take pictures), the archetypal portraits of those who have been called Pre-Raphaelite “muses,” or “stunners,”[5] are hung on the walls as well as on a central moveable accordion partition around which spectators can walk. This setup adds liveliness to the pictures: no longer displayed against a flat wall, they seem more three-dimensional. Among the sensuous portraits of female models, Venus Verticordia (1869; fig. 4) represents a red-haired woman holding an apple and an arrow. Every detail of her face and the things surrounding it—her hair, the honeysuckle, and the pink roses—is particularized, made essential and crucial. The exhibition of these iconic bust-length portraits, typical of later Pre-Raphaelite paintings, in the vicinity of naturalistic landscapes suggests the importance of direct observation of nature for the British school in both genres.

For non-Japanese speakers, the catalogue is an indispensable ally for navigating the exhibition as it includes English translations of the various wall texts. Two short texts written respectively by Christopher Newall and Joichiro Kawamura introduce the show. The first recalls that the rising middle class provided an important social context for the work of these artists; the second traces the links between the Japanese writer and artist Natsume Sōseki and John Everett Millais’ Ophelia (1851–52). Hailed as “a thing of considerable beauty” in Sōseki’s novel The Three-Cornered World (1906), the painting has ever since enjoyed a cult following in Japan. Organizers of the 2008 Millais exhibition in Japan and the 2012 Tate travelling exhibition of Pre-Raphaelite masterpieces chose not to use the painting for the poster as they feared it would encourage young women to commit suicide.[6]

The third section, smaller than the others, is less coherent. It features a diverse array of works from friends of the core Pre-Raphaelites, such as William Henry Hunt, George Price Boyce, William Dyce, as well as artists who are more closely associated with Aestheticism or Symbolism, namely Frederic Leighton, George Frederick Watts, or Simeon Salomon. In her recent book on the Pre-Raphaelites, Aurélie Petiot avers that Pre-Raphaelitism had little in common with Aestheticism, apart, perhaps, from the synesthesia so characteristic of Rossetti’s sensuous portraits of the 1860s, whose decorative backgrounds resonate with the more ornamental works of Aesthetic artists.[7] Yet Pre-Raphaelite Parabola leads the audience to imagine other links. In Frederic Leighton’s Mother and Child (Cherries) (1864–65; fig. 5), the pose adopted by the characters is classical while the slick handling is characteristic of polished academic art; it seems at first sight to offer a stark counter-point to Pre-Raphaelite avant-gardism. In his quest for a more academic kind of perfection, Leighton might seem to part ways with Ruskin’s demand for truth to nature. But seeing his paintings, and those of his contemporaries, in the context of this panorama convinces the viewer that far from negating the painterly medium, Leighton was creating works in which paint represented the only possible site for meaning. In his works, and the paintings of his Aestheticist peers, the very smoothness of the pigment opens up the possibility of access to truth. They do not deny the visual facts of their works—that is, their surface as facture or fabric—but rather their condition as mere shallow surfaces and fictive reproductions of the visible. At the center of their artistic endeavors is the idea that paint is in and of itself an equivalent to the world; where strokes are concealed, paint paradoxically comes to the fore, asserting its reality as substance as well as surface.

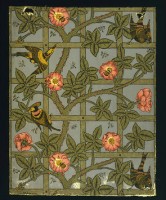

On view in the fourth and fifth sections are the works of Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, two friends who had studied together at Oxford under Rossetti. Burne-Jones, one of the best-loved artists of the period, is less unanimously praised today.[8] While in his medieval references and stylized figures he appears not as interested in everyday, ordinary subjects as his Pre-Raphaelite predecessors, his works nonetheless bear the imprint of Rossetti: they are imbued with a form of sincerity, as evidenced by the care for ornamentation that is deployed in them. In The Tree of Forgiveness (1881–82; fig. 6), Phyllis, a character from Ovid’s Heroides, emerges from an almond tree, her hair mingling with its flowers, to embrace her lover Demophoön. In the following room, Trellis from 1862 (fig. 7), the first wallpaper produced by the company seems to prefigure Burne-Jones’s motifs. Plain and naturalistic, this type of design would then evolve into more sophisticated patterns and luxurious furniture, ones that betrayed the original purpose Morris had destined for them as they became too expensive to be bought by craftsmen. On view in the show are also a variety of stained-glass works, pieces of furniture, tapestries, fabrics as well as ceramic tiles by William De Morgan. They are reminders of Ruskin’s rallying cry to create beauty against mass production.

Throughout the show we are reminded of Ruskin’s particularly timely approach to modern art. By encouraging sincerity as a means of progress, by going back to feudal models of production as a way of fighting against the dehumanization of industrialization, Ruskin and his followers speak to our contemporary ecological preoccupations. Pre-Raphaelite Parabola begs the question of the Pre-Raphaelites’ legacy today. As Aurélie Petiot has demonstrated, their universe is so fertile that it resonates anew in popular and queer cultures.[9] One criticism that might be ventured against the show is that it promotes Pre-Raphaelitism as a brand, when in fact it has little to do with the Pre-Raphaelites per se. Whether it is because their stories (of companionship and amorous rivalries) are entertaining or because they speak to an ongoing fascination for a certain archetype of beauty, the Pre-Raphaelites remain crowd pleasers. Between the different sections, a “selfie room” allows visitors to pose as if they were in the show’s poster. The superimposition of one’s self next to Venus Verticordia can seem a ludicrous form of entertainment, and yet it is more than a mere gimmick, for in this immersive experience one cannot help but feel a connection to these artists. For this show, the past and the present are within each other.

Sarah Gould

Associate Professor

Paris 1-Panthéon Sorbonne

sarah.gould[at]univ-paris1.fr

[1] For the history of Pre-Raphaelite exhibitions in Japan up to 1993, see Joseph Kestner, “The Pre-Raphaelites,” The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies (Fall 1993).

[2] Oxford English Dictionary, “Parabola,” accessed August 15, 2019, https://www.oed.com/ [login required].

[3] Ibid.

[4] Christopher Newall, Parabola of Pre-Raphaelitism (Tokyo: Artis Inc., 2019), 183.

[5] See Henrietta Garnett, Wives and Stunners: The Pre-Raphaelites and Their Muses (London: Macmillan, 2012). Quoted in Aurélie Pétiot, Préraphaelisme (Paris: Citadelles & Mazenod, 2019), 170.

[6] See different articles relating the scandal published in Benjamin Secher, The Telegraph, August 7, 2014; Maev Kennedy, The Guardian, August 7, 2014. On the Ophelia-cult in Japan, see the work of Yoshihara Yukari, such as the summary of a talk she gave at Stanford University in 2018. See the description of the talk at this link: https://sgs.stanford.edu/events/ophelia-cult-japan.

[7] Pétiot, Préraphaelisme, 191.

[8] Attested by the more conservative reviews of his 2018 show at Tate Britain. See Jonathan Jones, “Edward Burne-Jones review—art that shows how boring beauty can be,” The Guardian, October 22, 2018; Waldemar Januszczak, “Art review: Edward Burne-Jones, Tate Britain,” The Sunday Times, October 28, 2018.

[9] Pétiot, Préraphaelisme, 204.