The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

[Ragpickers] represent primitive mankind in the big city, blissfully ignorant of laws, happy with nonentities, imbued with their vegetative way of life, retiring from society like a troglodyte of the caves.

- L’Histoire, April 3, 1870

When the daily periodical L’Histoire published these words in 1870, they were describing a profession that was already being legislated out of existence. Ragpickers (chiffonniers) had collected discarded cloth, glass, metal, bone, and many other materials in order to resell them to industries for recycling in France for centuries. Although ragpickers continued their work in Paris well into the twentieth century, decrees in 1870 and 1883 attempted to limit their access to the refuse on which they made their living, spelling the beginning of the end of their profession. In the mid-1880s, their shanty towns in the heart of Paris were demolished, forcing their relocation to the industrial suburbs on the perimeter of the city, primarily the thirteenth, fourteenth, eighteenth, and twentieth arrondissements. Known as the zone militaire (military zone), this area was taken up by the fortifications that Louis-Philippe had constructed around the city in the 1840s, and the ragpickers were among the zoniers who illegally constructed shacks here. As a result, both Clichy, which abutted this zone, and its neighbor, Asnières, became associated with chiffonniers. Additionally, warehouses for the collection of the ragpickers’ materials were built as the outskirts of Paris became increasingly industrialized.[1] These marginalized people were a continued source of fascination for artists throughout the mid-nineteenth century. From Honoré Daumier and Charles Baudelaire in the 1840s and ’50s, to Édouard Manet and Jean-François Raffaëlli in the 1860s and ’80s, writers, caricaturists, and painters alike thematized the lives of the lowly ragpickers.[2]

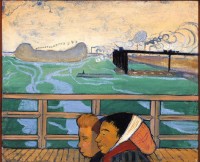

Émile Bernard’s Ragpickers of Clichy (1887; fig. 1) has long been regarded as a simple painting of two ragpickers in a suburb: their large, distorted heads relegated to the bottom third of a canvas taken up by a depiction of the Seine and the manufacturing that was flourishing in Clichy and Asnières. While Asnières drew more attention as an avant-garde subject through the work of Georges Seurat, Vincent van Gogh, and Raffaëlli, Clichy more often served as an industrial backdrop—most famously as the location of the smokestacks in Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières (1884). In Karl Baedeker’s 1900 travel guide, Paris and environs (Paris and its surroundings), a single line of text is used to describe the area: “Clichy (33,900 inhabitants) . . . [is] uninteresting.”[3] Bernard, raised in Asnières, also used the factories of Clichy as a backdrop, but unlike Seurat, his subjects are not Parisian visitors but inhabitants of the area. While these ragpickers may still work in the city, they are not the Parisian chiffonniers of the previous generation, but a population of outsiders living on the edge of the city.

Ragpickers of Clichy is notable for Bernard’s bold use of color and cloisonnisme. The strong, dark outline surrounding both the railing and the women underscores the linearity of the backdrop, which contrasts with the rounded forms of the figures’ silhouettes. Brightly colored water is broken up by streams of lighter blue as rings of smoke drift over the industrial skyline.[4] A dramatic cropping of both the walkway and the women’s bodies draws attention to the figures below. The woman in the background has blonde hair, a flat forehead, pursed lips, and small chin, her expression melancholic as she stares forward. The dark-haired figure closest to the viewer is dominant not only for her position, but also because of her patterned clothing and bulbous, elongated head. Her hair stretches back over her extended skull, the unusual length of which is emphasized by the white cloth that reaches over her crown.

While Bernard certainly utilized techniques of simplification and non-local color, I argue that the woman’s elongated skull was not an artistic exaggeration, but instead a reflection of reality. Though little known today, artificial cranial modification—the often dramatic altering of the shape of the skull—was practiced by peasants in France through the late nineteenth century. In his portrayal of these marginal people in a peripheral location, Bernard also chose to employ another bodily marker of difference: cranial modification. Far from a purely aesthetic choice, the artist’s inclusion of a person who practiced this archaic tradition emphasized the alterity of the figure. Like the occupation of rag picking, cranial modification was a dwindling, but still surviving practice—one that was being phased out by an increasingly industrialized society. Although in this period Bernard was certainly less engaged with naturalism than the impressionists, a revaluation of this painting with cranial modification in mind shows his concern with the rapidly changing modern world, demonstrated through the stark contrast between the outmoded ragpickers and their industrial backdrop. Furthermore, it serves as a reminder that despite the modernization that was sweeping France, there were real, bodily reminders of France’s past—a past that likely seemed distant and archaic to Parisians, but that was actually concurrent and visible in the outskirts of their city. Although historians often focus on the transformation of Paris, it is important to recognize how ancient practices were still part of this new world, a point that Bernard clearly makes through his contrast of antiquated tradition and modernity in Ragpickers of Clichy.

Artificial Cranial Modification in France

Although perhaps best recognized through its presence in ancient South America, artificial cranial modification likely began in France as early as the fourteenth century and persisted in many of France’s northern, western, and southwestern provinces through the late nineteenth century as a holdover from medieval times.[5] A number of artificially modified skulls dating to the seventeenth century have been found during excavations in Paris, while others, from Voiteur in eastern France, date to the fourth or fifth century CE.[6] The custom involved firmly binding an infant’s head shortly after birth and likely emerged out of an attempt to protect the soft spot on its skull, as evidenced by books on obstetrics and midwifery from the seventeenth to nineteenth century.[7] However, De la grossesse et accouchement des femmes (On the pregnancy and childbirth of women), a book written by Dr. Jacques Guillemeau in 1621, also recommends binding an infant’s head with bandages to give it a more pleasing shape if it is ill-formed at birth.[8] Although some doctors, like Guillemeau, endorsed the practice, many writers in the eighteenth century began to condemn it as unnecessary and possibly dangerous. Jean-Jacques Rousseau provided a description of it in his novel Émile (1762), in which he mocks midwives who mold the heads of infants to alter their appearance, disparaging their attempts to improve God’s work.[9] Despite these debates, by the early to mid-nineteenth century the tradition was still practiced in many parts of rural France in part due to aesthetic affinities.[10] And while the practice seems to have died out among Parisians before the late nineteenth century, it continued and certainly would have been seen in the city as peasants migrated to Paris seeking work.

Unfortunately, because head binding was traditionally practiced by illiterate peasants, the records we have about the process are from the perspective of outsiders. Fernand Delisle, a doctor touring asylums in France in the late nineteenth century, claimed that the French wrapped the skull so tightly that the baby would cry for hours after the band was applied.[11] He also noted that the cloth was rarely taken off, which resulted in heavy lice infestations and skin problems for the child. While Delisle’s source was a man who worked at an asylum in Normandy who reported a number of methods of head binding, his stories were filtered through an educated Parisian, Delisle, who, based on his dramatic description of the process, evidently regarded the procedure as primitive.[12] However, it’s likely that one of the men exaggerated the horror of the practice, as earlier reports, such as those written by Dr. Guillemeau, did not indicate that it was necessary to use a great deal of force. While it is possible that Delisle recorded the actual, unidealized process, such extreme pressure would not have been needed for an alteration of the shape of an infant’s head—even a radical one. The consistent binding of the soft bones of an infant’s skull would produce the effect over time without causing pain and almost certainly would not have had an effect on lice.

Additionally, although head binding seems to not have been particularly gendered in its early incarnations, by the nineteenth century that had started to change. While males continued to have their heads bound, the practice was slowly becoming more common among females.[13] In 1834, Achille Foville noted that over 50 percent of the patients at the asylum at Saint-Yon, Essonne, in northern France, had undergone artificial cranial modification. However, only about 38 percent of those patients with modified heads were male.[14] The gendering of this practice further suggests that as it continued to evolve, it became less a misguided notion of protecting the heads of children than an aesthetic effect. If head binding was performed only for health reasons, then the practice would have been seen equally among the genders. Its prevalence among women indicates that cranial modification was likely seen as a mark of femininity.

Since head binding in France occurred over a large geographic area, there were natural variations in the process. People in different regions used handkerchiefs, bandeaus, caps, or bands of cloth to bind the heads of infants after their birth (fig. 2). Many different skull shapes also resulted from head binding. Two examples of these variations can be found in the collection of the Musée de l’Homme (figs. 3, 4). In the first, seen on the left, the skull was lengthened at a low angle, referred to as a bread loaf deformation.[15] The second shape, seen in both the skull on the right and the one shown in figure 4, shows that the head was pushed up and back, resulting in a taller skull with a steep angle from the crown to the forehead.[16] This was called the Toulouse deformity, as it was commonly seen around the city in southeastern France. However, not all shapes were employed regularly within each region—even in a single family, multiple shapes could be seen.[17] The actual binding of the head seems to have been performed by midwives or mothers after birth, and variations in the education of the midwife and her consistency in binding the head from baby to baby could explain this disparity, as well as the ways in which the mothers continued to bind the head over time.[18]

Beyond queries about the motivations behind this practice and its variations, there is the question of its visibility for a Parisian audience. As middle-class individuals like Bernard traveled outside of the city, they would have observed people who had undergone this process throughout France, in addition to those peasants with artificially modified heads who had relocated to Paris. Furthermore, it is likely that modified skulls were on public display in the late nineteenth century with the opening of the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro (Ethnographic Museum of the Trocadéro) in 1877. The Trocadéro was a colonialist endeavor that aimed to articulate the superiority of white Europeans over other races through both cultural and physiological examples.[19] Reminiscent of an enormous curiosity cabinet, the museum displayed artwork and religious objects collected from French colonies in Africa, as well as religious items from the provinces intended to demonstrate the progress of man.[20] Displayed with only the name of the people who created them, these objects served as a visual justification for both colonialism and France’s attempt to homogenize its provinces. The “otherness” of the objects was emphasized by the cluttered environment, which encouraged people to gawk at the strangeness and primitiveness of both colonized peoples and provincial peasants in one space. This message was furthered with displays of human skulls, which highlighted the evolution of man and the role anthropologists believed race played in it.[21]

Although no records confirm that artificially modified skulls were displayed among these objects in the late nineteenth century, their presence in the Musée de l’Homme’s collection today suggests that they were. The Musée de l’Homme is the modern successor of the Trocadéro, having inherited both its site and much of its collection from the earlier museum. Furthermore, the fact that the Musée de l’Homme currently owns modified skulls that were donated by the anthropologist Paul Broca, who died in 1880, makes it likely that the Trocadéro had these human remains in its collection at an early date. Displaying the skulls would have been appropriate for the museum, offering another exhibit that accentuated the backwardness of provincial peasants who were unwilling to let go of their ancient customs, as well as underlining the progress that the modern French had made since that period. Thus, not only would Parisians have seen examples of artificial cranial modification through living people, but they also may have seen skulls featuring the practice on display in the Trocadéro. This likely would have drawn attention to the people with modified skulls who they encountered in their daily lives, suggesting that the practice was obsolete and making those individuals seem like living embodiments of France’s ancient past. In this way, as the Trocadéro celebrated France’s colonialist endeavors and the triumph of evolution, it also emphasized the contrast between the ideal France that the government was working to portray and the reality of daily life in a country where antiquated traditions continued.

Ragpickers on the Periphery

The old-fashioned custom of head binding would have marked peasants emigrating from the countryside to the city, setting them apart from the more “modern” workers of Paris. It likely served both as a sign of their dissimilitude and, to some extent, their primitiveness. Likewise, the ragpickers, although firmly entrenched in daily Parisian life, were regarded as “others” by the rest of the city. Although ragpickers were not particularly noted for participating in the custom, the occupation was one that drew outsiders and didn’t require any skills, making it a likely profession for those newcomers who were unable to find other work, and thus it was more likely that people with modified heads would be introduced into the chiffonnier population.

Discussed in everything from poetry, plays, and novels to sanitation treatises—both in relation to the role they played in removing trash and the health concerns surrounding the lack of sanitation in their shanty towns—ragpickers fulfilled vital functions in the removal and recycling of garbage. The exact number of ragpickers working in Paris in the late nineteenth century is uncertain. However, from 1886 to 1900, the Paris Board of Health, the Labor Department, the police, and various worker’s organizations estimated that between 5,000 and 40,000 ragpickers were active in the city. These disparate estimates evolved from both the visibility of the chiffonnier in the public imagination and the political motivations of those providing an exact number; some inflated the figure in hope of convincing others that new regulations against the ragpickers would have a widespread, detrimental effect on the lives of many Parisians. In his study of the nineteenth-century ragpicker, political scientist Alain Faure proposed a more reasonable estimate of between 4,950 and 7,050 based on impartial studies.[22] These numbers would have fluctuated throughout the year as seasonal employees, such as construction workers, became ragpickers in the winter.[23]

It is also likely that the number of ragpickers working in Paris declined toward the end of the nineteenth century. There were a number of ordinances that attempted to control and limit the freedoms of the men and women performing this type of labor. In 1823, chiffonniers were officially required to have badges indicating their profession, although it seems this law was never strictly enforced. The city ceased making the badges in 1870, when it implemented a new ordinance that called for concierges to put out their garbage just before collection in the morning. This was followed by a second decree in 1883—due to the first being ignored—which gave a small concession to the ragpickers by allowing the trash to be put out an hour before collection so they could perform their work.[24] A division emerged between those who collected on the street and those who developed relationships with concierges in order to have earlier access to the garbage before it was taken to the street.[25] The attempts to increase control over the ragpickers is unsurprising due to their controversial reputation as shadowy, dangerous figures living outside of society, prone to alcoholism and likely to drift into illegal activity. This reputation, as well as concerns that criminals were better able to thieve by hiding among the chiffonniers who worked at night, is likely what inspired the stricter regulations.

Alternatively, ragpickers were also highly romanticized. The chiffonnier-philosophe (ragpicker-philosopher) was a character that lacked the burden of an hourly job and who appeared in works by authors and artists alike, including Manet, Baudelaire, Charles-Joseph Traviès, and Félix Pyat. In his 1842 book Les Industriels, métiers et professions en France (Industrialists, trades, and professions in France), writer and journalist Émile de la Bédollière claimed that:

As soon as he is an armed chiffonnier, as soon as he becomes familiar with the ignominy of this dirty profession, after having adopted it out of necessity, he continues it by association. He takes pleasure in his nomadic life and independence. He looks with contempt on the slaves who lock themselves up from morning ’til night in a workshop behind a workbench. While others, living machines, regulate their time on the march of clocks, he, the chiffonnier-philosophe, works when he wants, rests when he wants without memories of the day before, without worries of tomorrow. . . . Subject to all privations, the chiffonnier is proud because he thinks he is free.[26]

Writers projected a unique type of freedom onto the ragpicker, transforming him into a reflection of the bohemian artist. In conflating the unrestricted chiffonnier and the bohemian artist, authors gained a vehicle through which they could assert their own status as outsiders, as figures on the periphery.[27] Baudelaire’s “Le Vin de chiffonniers” (Wine of the ragpicker) from Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil; 1857) serves as one of the best-known examples of this characterization; in it he romanticizes the existence of a drunken ragpicker who is downtrodden, but also wanders free from the constraints of bourgeois society. A further facet of this myth of the chiffonnier-philosophe can be seen in stories involving either a rise to or fall from fortune, where a man with the lowliest of beginnings gained a fortune or an aristocrat fell from grace and was forced to scavenge in the trash to survive.[28] These tales blurred the boundaries between the classes, providing a level of ambiguity to this commonplace figure that was further echoed in his or her dress. As Marnin Young explicates in Realism in the Age of Impressionism, the fact that ragpickers dressed in the discarded clothing of the bourgeoisie whose trash they foraged through meant they could not be as easily identified by dress as many other classes and professions—yet another way in which the chiffonniers stood apart from their fellow Parisians.[29]

Such authors brought light to their practices, removing the mystery that surrounded their everyday reality by portraying them as “noble savages . . . the hunters and gatherers of the urban jungle.”[30] For instance, in Barrie M. Ratcliffe’s study of the profession, he describes the exoticization of these fringe figures in the first half of the nineteenth century, which helped to assuage the fears of the public. This view helps explain the fascination the chiffonniers held for so many artists and writers.

Painters were likewise engrossed by the ragpicker for many of the same reasons as novelists during this period. One such artist, Raffaëlli, was a realist who exhibited with the impressionists and was well known for his paintings of the outskirts of society. He is a model for the type of imagery related to ragpickers that Bernard may have seen around Paris.[31] Raffaëlli’s Le Chiffonnier (1879; fig. 5) is typical of his paintings of the profession. The isolated figure stands in a somber, largely empty industrial wasteland, smokestacks visible behind the brush that surrounds him. He is framed by a colorless sky, drawing attention to his seclusion as he peers into the distance, a small dog at his feet. His clothing and accoutrement are carefully rendered, leaving the viewer no doubt as to his role. Raffaëlli’s depiction is undeniably realist. While Bernard utilized simplified forms and bold colors in Ragpickers of Clichy, Raffaëlli concerned himself with rendering the life and environment of a chiffonnier in the period.

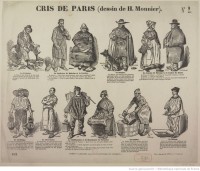

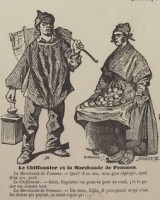

Contemporary popular media similarly illustrated social types and would have been another source used by Bernard in his work. In her book The Spectacular Body, Anthea Callen discusses the “Cries of the City,” prints that detailed the costume and accessories typical of various types of urban workers, and physiognomies, descriptions or images of various personality and social types, as indications of a growing desire for the increased legibility of both class and personality types.[32] The former contained illustrations of various professions and the phrases they typically uttered. Henry Monnier’s engraving Cris de Paris, N. 2 (Cries of Paris, no. 2, 1853; fig. 6) is one such example. It shows a dozen urban workers, detailing their vestments to help the public clearly identify them. The chiffonnier is shown with a noticeably dark face (fig. 7), his clothing shaded and baggy, while his hands are full of his tools. This type of imagery, intended to help the public read not just profession, but also class, was ubiquitous and could be found in books, prints, and even on playing cards.

Another symptom of the growing concern over social legibility, as well as the desire for a homogenization of French society, can be found in the work of authors like Alexandre Privat d’Anglemont and Victor Fournel, who recorded the workday and lifestyle of the ragpicker, drawing attention to their language and customs as if they had been observing an exotic culture. Despite the essential function of the ragpicker in Parisian society, in many ways these people were not regarded as part of Paris. Like many of the peasants who immigrated to the city in the nineteenth century, the chiffonnier spoke in various patois, or regional dialects. In Louis-Auguste Berthaud’s encyclopedia entry “Les Chiffonniers” of 1841, he describes them as coming from “all countries,” indicating the heterogeneous nationalities of the population.[33] Various authors associated the ragpickers with groups of outsiders, firmly othering them even as they touted the chiffonnier as an integral part of the sanitation system of the city of Paris. Privat d’Anglemont unfavorably compared the ragpicker to Native Americans, calling him “the savage of Paris . . . it is the insolent, skeptical, ignorant, credulous, and superstitious thug, but much more wicked than the savage of the great lakes of North America.”[34] Likewise, Fournel also participated in racist rhetoric, referencing medieval ghettos as he described the modern chiffonniers, stating that “the ragpickers are disdainful of the bourgeois: they reproduce only with each other; they form a society of their own that has its own customs, a language of its own, a neighborhood of its own, which one can compare to the hideous and mephitic streets where the Jewish population of the Middle Ages was cornered, swarming and sinister.”[35]

It is certainly true that the ragpickers lived in insular communities, called cités, that were moved to ever-more-remote locations throughout the century. These cités may have been intentionally self-segregated by the chiffonnier, as Fournel suggests, but they were likely also avoided by others due to concerns about sanitation. The Board of Health saw isolation as the only prudent move to protect the rest of the Parisian population from the filth and disease that were seen as part of the ragpicker’s way of life. Victor Hippolyte de Luynes’s Rapports sur les dépôts de chiffons (Reports on rag storehouses), for example, recommends building cités outside of central Paris in order to help guarantee sanitary accommodations.[36] This movement toward the perimeter began with Haussmannization (1853–70) but would continue throughout the nineteenth century as various forces within the city worked to shove the unsightly ragpicker communities out of the center.[37]

Although this was a literal migration, the movement of the ragpickers into the periphery also served as a reflection of their status. Not only were their homes relocated outside of Paris—though by definition they had to go into the city to complete their work—but the chiffonniers had always occupied a marginal place in society. Grouped together with beggars, gypsies, and street performers, the ragpickers now had a home territory that matched their position in the social hierarchy. In 1894, Le Monde illustré (The world illustrated) romanticized this move, giving the ragpickers autonomy, as A. Boisard wrote, “[They] have moved to the countryside, as if Saint-Ouen, Pantin, or Clichy could possibly suggest an open prairie.”[38]

Clichy quickly became one of the best-known residences of ragpickers. It was located just outside the walls of Paris and across the Seine from Asnières, where Bernard was raised. While Asnières was known as a place where working-class Parisians went to enjoy the country, Clichy did not garner the same reputation. On the contrary, Clichy was notable only for how thoroughly it seems to have been ignored by writers, artists, and newspapers in the late nineteenth century.[39] Even texts about the suburbs of Paris reveal little about the town. Adolphe Laurent Joanne’s 1878 Les environs de Paris illustrés (The illustrated environs of Paris) provides only three sentences about the town, describing its ancient history and a saint who was a priest there in the seventeenth century. Joanne finishes his section on Clichy by noting that many factories occupy the area. In comparison, his section on Asnières has an illustration as well as five times more text containing descriptions of its architecture and the possibilities for boating—as well as the park’s state of disrepair.[40] Clichy’s lack of notable traits is telling. The suburb was apparently a place designated only for industrial development with no features to draw tourists or Parisians looking to spend a day away from the city. More often mentioned in texts concerning the zonier or industry, Clichy was not only peripheral, but forgettable.

The contrast between Bernard’s privileged, bourgeois upbringing and the poverty that marked the lives of the ragpickers in their cités across the river could hardly have been missed by the artist. He painted Asnières multiple times in the mid-to-late 1880s, usually focusing on the boundaries of the area: the river, bridges, and gates. As Young has stated, Asnières and its surrounding suburbs became an avant-garde subject around 1886—at the same time Bernard began painting here. And, like other modern painters of the period, Bernard frequently titled his works with their location in order to emphasize the marginality of the region he was illustrating.[41] Clichy, just across the river from Asnières but a world away from the life of Bernard’s youth, would have made an engaging setting for an exploration of both the periphery and fringe figures in society.

Ragpickers of Clichy

I would now like to return to Bernard’s painting Ragpickers of Clichy in order to show how his representation of chiffonniers in the outskirts of Paris contains a conspicuous portrayal of cranial modification. Although the elongation of the figure’s head in the foreground has generally been regarded as Bernard’s attempt to move away from naturalism, it must be reevaluated with the practice of cranial modification in mind in order to understand how he was working to show both modernity and France’s past in this image.

In the literature on Bernard, Ragpickers of Clichy is typically seen as a noteworthy step toward the artist’s stylistic innovations in pictorial symbolism and as an early example of cloisonnisme. Both Mary Anne Stevens and Fred Leeman discuss the painting in their catalogues on Bernard’s work, commenting on the arabesques of the smoke and water in contrast to the severe linearity of the bridge.[42] They also address the unusual appearance of the women: Stevens in regard to the shapes of the heads and Leeman their faces. Stevens observes that the painting marks a move away from naturalism, which is “reinforced by the stylised heads of the two women in the foreground.” She also notes the influence of Japonism in the work.[43] Similarly, Leeman acknowledges the figures’ odd appearances, but his comments relate more closely to their faces. He indicates that their yellow-tinged skin and the schematic treatment of the eyes, in addition to the severe cropping of their bodies, are all elements of Japonism.[44] Although both scholars touch on elements that characterize the figures as unusual—and certainly the work still marks a departure from the impressionist concern with the natural world—Bernard’s attention to a factual anatomical difference may show a greater concern with naturalism than previously understood.

As peasants migrated into the city—including some who became ragpickers—it is likely that Bernard would have seen examples of artificially modified heads. More than merely depicting reality, it is likely that Bernard used this strange feature as a way to emphasize the difference of the chiffonniers—transforming them from simple French ragpickers into something more ancient. This effect is further enhanced by the contrast between the women and the factories visible in the background. The simple wooden railing that divides the canvas evokes aesthetic techniques used in Japanese Edo prints, which were gaining popularity at this time. As these “primitive” women walk by the water, the “Japanese” boundary created by the railing separates them from the industrial activity taking place behind them, offering a way to delineate space while flattening the image. The stark division of the canvas is echoed in Bernard’s cropping of the figures, which not only creates the impression of momentary observation, but also draws the viewer’s attention to the heads of the women. The smoke rising out of the stacks not only creates abstract shapes, but it also serves as a symbol of two different visions of France: one of the future, showing progress, steaming away above, and one of the past, represented by the ragpickers who display a medieval custom that, like the ragpicker herself, is fading away. This contrast helps to reinforce Bernard’s attempt to archaicize these women.

Even Bernard’s choice to paint female chiffonniers rather than male ones serves to other the figures. Although the majority of contemporaneous artists and writers detailed male ragpickers, over a third of ragpickers were women.[45] The women were largely ignored, relegated to invisibility in a profession in which they were integral.[46] This unwillingness to illustrate females is likely due to the romanticized conception of the profession. As noted above, writers and artists emphasized the idea of the chiffonnier-philosophe, who lived in freedom, choosing his own hours and answering to no man. This contrasts starkly to how women were viewed in the mid-nineteenth century, when pseudoscientific theories about the lesser cranial capacity and structure of the female’s brain were used as justification for keeping women out of the workforce.[47] The idealized freedom that people associated with ragpickers would thus have been an inappropriate association for women. The trend of focusing on male chiffonniers makes Bernard’s representation of female ragpickers unusual. Not only did he paint a marginalized people in a marginal location with a physical sign of their dissimilitude, but he also chose to paint the marginalized sex as well.

Ragpickers of Clichy is not the only work in which Bernard painted female ragpickers. His Quai de Clichy (fig. 8), also from 1887, shows a woman who looks similar to one of the women in Ragpickers, now walking with another figure. The location, although not identical, is close to the same area, near the bridges of Asnières. However, the leafless trees and road covered in snow indicates that this is a winter scene. A striking new perspective, with the walkway becoming less distinct as it recedes into the distance, dissolving into shades of gray, also leads the viewer into the painting. Although elements of the figure in the foreground of Ragpickers are reused here, it seems as if the woman’s features and clothing have been divided between the two women in Quai de Clichy. The green striped coat and red scarf are featured on the figure on the right, while the facial features and bandeau have been transferred to the figure on the left. In addition, while the woman on the right is shown in a three-quarter view, the woman on the left maintains a closer relationship to the strict profile of the figures in Ragpickers. This profile again reveals an oddly long skull, emphasized by the white of her bandeau (fig. 9).[48] Furthermore, without the cloth covering her hair, the viewer can see that her hairstyle is not a high bun, which might make her skull appear longer, but rather a ponytail. Another element that Bernard appropriates from his Ragpickers is the inclusion of modern industry. As in the other painting, smoke rises out of buildings or a train over the heads of the women, again offering a contrast between the provincial traditions of the past and the progress of modernity.

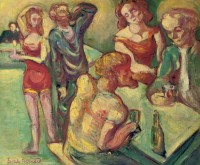

Both of these paintings can be viewed as characteristic of Bernard’s ongoing experimentation in 1887. His work in this period is notable for its breadth of both subject matter and style. This is not yet the Bernard who painted with Gauguin in Brittany in 1888 and 1889, who was firmly committed to symbolism and its tools of non-local color, extreme flattening, and cloisonnisme as he depicted Breton peasants. This Bernard was still attempting to discover the correct direction for his art as he created works inspired by Seurat, Paul Cézanne, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Louis Anquetin, and van Gogh—all within the space of a year. The young artist oscillated between scenes of bordellos and cafés concerts, landscapes, still lifes, and intimate portraits of friends and family, creating works in 1887 as divergent as Ragpickers of Clichy, Au cabaret (At the cabaret; fig. 10), and Portrait of Père Tanguy (fig. 11). In Ragpickers of Clichy, Bernard borrows from the subject matter of the realists, impressionists, neo-impressionists, and post-impressionists as he balances elements of exaggeration and naturalism, moving toward his fully realized symbolist style of the next few years. While Bernard’s work is often thought of as flat and primitivizing, this canvas is an intermediary step that balances his use of cloisonnisme and arabesques with an impressionist’s interest in modern life as he records women in the industrial perimeter.

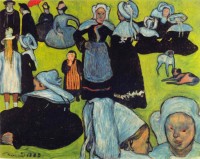

Within a year of painting Ragpickers of Clichy, Bernard would travel to Brittany, where he continued to engage with marginalized women as he painted its peasants. His most famous work, Breton Women in the Meadow (fig. 12), from 1888, likewise shows exaggerated color, cropped figures, and illustrates a people regarded as other. Brittany was a region that was often linked to the past, more related to both the ancient Celts and medieval French than the Parisians who vacationed there to admire the beautiful landscape and archaic dress of the people.[49] Highly flattened, the bright background of Breton Women frames the figures, contrasting with their primarily monochromatic garments. The elaborate bonnets worn by Breton women were well known and frequently rendered in art portraying the region. In his painting, Bernard accentuated this by featuring the profile of a woman in the center of the foreground. As with his Ragpickers, he severely crops this figure, turning her face away from the viewer to allow for a three-quarter view of the bonnet. The form of the headdress mimics that of the Toulouse deformity, in which the head appears to stretch upwards at a high angle. Records from the Musée de l’Homme indicate that this type of cranial modification indeed occurred in Brittany, meaning that Bernard may have used the practice as a sign of otherness as he did in Ragpickers of Clichy.

His focus on Breton women—not just in this painting, but in much of his work from the region—likely stemmed in part from their charming provincial costume. However, beyond their clothing, Breton women were also ideal vehicles for the depiction of superstition and deep religiosity. The association of women as keepers of religion in France was already well established by the mid-nineteenth century, but this concept was even more prominent in Brittany, where outsiders regularly commented on the perceived excesses of Breton Catholicism—often referring to them as superstitious and even savage.[50] Breton women were regularly painted not just in worship, but participating in mass prayer and processions that recalled medieval religious practices. This is seen in many works made by avant-garde and academic artists in Brittany in this period, including Gauguin, Paul Sérusier, Maurice Denis, and Jules Breton. Just as Bernard’s choice of female ragpickers heightened their perceived otherness, so too did his and other artists’ decision to paint the women of Brittany. Likewise, in the work of his fellow avant-garde artists we see that Bernard was not alone in his combination of observation and exaggeration. As Allison Morehead proposes in her 2017 book Nature’s Experiments, many symbolist artists were engaging with experimental science as they explored new techniques for illustrating the interior life of men and women. In so doing, they continued to incorporate elements of naturalism even as they experimented with abstraction.[51] Far from unique, Bernard’s inclusion of artificial cranial modification in his painting should be regarded as a symptom of the avant-garde’s continued engagement with naturalism throughout the 1880s and 1890s.

Although the existence of artificial cranial modification in France in the nineteenth century is undeniable, how much a Parisian artist like Bernard knew about the practice is uncertain. I have yet to find an instance in which an artist directly commented on it; instead I have established contemporaneous knowledge of cranial modification primarily through the writing of anthropologists. Statistics from those anthropologists suggest that the practice was widespread enough that Parisians—particularly those who, like Bernard, traveled to provincial areas during this time—would have come into contact with the unusual tradition regardless of how well they understood it. By examining these paintings, as well as prevailing attitudes about ragpickers, a case can be made that Bernard included cranial modification in his paintings. The trend of depicting the outskirts of Paris, as well as Bernard’s interest in primitivism, may have encouraged him to include this unusual anatomical feature as a sign of difference.

Through an examination of the practice of artificial cranial modification in France, as well as popular conceptions of ragpickers, Bernard’s paintings can be seen in a new light. Although he undeniably exaggerated form and color in these images, the distortions of the heads of his figures may be viewed as more true to life than previously thought, revealing a greater concern for naturalism. Furthermore, the attention Bernard gave to this fading practice may have been a way for him to acknowledge the continuation of an ancient tradition even as he painted a modern, industrial landscape. Choosing to show a woman with artificial cranial modification and making her part of a dying profession allowed Bernard to illustrate the palimpsest that was Paris’s population: a city that was moving toward modernity but had real, physical reminders of the past found not just in architecture, but in the very bodies that inhabited it.

I would like to thank Nancy Locke for her instrumental guidance and many helpful comments, as well as William Dewey for his invaluable information regarding this topic. I would like to express my gratitude to the art history department at Pennsylvania State University, the Babcock Galleries Endowed Fund, and the Francis E. Hyslop Memorial Fellowship. With special thanks to the Musée de l’Homme for allowing me access to their collection of modified skulls, and Liliana Huet for her help while there. Thank you to Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide and the anonymous peer reviewer. I would also like to thank my family and friends for their enthusiasm and support regarding this project. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are mine.

Epigraph: L’Histoire, April 3, 1870, cited in Alain Faure, “Sordid Class, Dangerous Class? Observations on Parisian Ragpickers and Their Cités During the Nineteenth Century,” in Peripheral Labour? Studies in the History of Partial Proletarianization, trans. Lee Mitzman, ed. Shahid Amin and Marcel van der Linden (Cambridge: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1997), 163. L’Histoire was a daily publication produced in Paris from February 2, 1870 to September 11, 1870.

[1] L’Histoire, 168–69, 173.

[2] For more on ragpickers and the periphery, see Justine Mie d’Aghonne (Louise Justine Augusta Philippine Lacroix), Les Mémoires d’un chiffonnier (Paris: E. Plon, 1880); Alexandre Privat d’Anglemont, Charles Baudelaire, and Alfred Delvau, Paris inconnu (Paris: Adolphe Delahays, 1861); Marilyn R. Brown, Gypsies and Other Bohemians: The Myth of the Artist in Nineteenth-Century France (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1985); Richard D. E. Burton, Baudelaire and the Second Republic: Writing and Revolution (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press: 1992); Faure, “Sordid Class, Dangerous Class?”; Austin Gough, “French Workers and Their Wives in the Mid-Nineteenth Century,” Labour History, no. 42 (May 1982): 74–82; Nancy Locke, “Unfinished Homage: Manet’s ‘Burial’ and Baudelaire,” The Art Bulletin 82, no. 1 (March 2000): 68–82; John M. Merriman, The Margins of City Life: Explorations on the French Urban Frontier: 1815–1851 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991); Molly Nesbit, Atget’s Seven Albums (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994); Félix Pyat, Le Chiffonnier de Paris: Grand roman dramatique (Paris: A. Fayard, 1892); Barrie M. Ratcliffe, “Perceptions and Realities of the Urban Margin: The Rag Pickers of Paris in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century,” Canadian Journal of History 27 (August 1992): 197–233; Dietmar Rieger, Diogenes als Lumpensammler: Materialien zu einer Gestalt der französischen Literatur des 19. Jahrhunderts (Munich: W. Fink, 1982); Jerrold Seigel, Bohemian Paris: Culture, Politics, and the Boundaries of Bourgeois Life, 1830–1930 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999); Alphonse Signol and Stanislas Macaire, Le Chiffonnier (Paris: Chez B. Renault, 1831); and Marnin Young, Realism in the Age of Impressionism: Painting and the Politics of Time (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015).

[3] Karl Baedeker, Paris and Environs, with Routes from London to Paris; Handbook for Travellers, 14th ed. (Leipzig, Germany: K. Baedeker, 1900), 209. Emphasis in the original.

[4] It is unclear what the object at the top left of the waterline is. The color suggests it is smoke, steam, or a cloud, but its location and firm outline makes those options unlikely.

[5] Baedeker, Paris and Environs, 201.

[6] Ernest-Théodore Hamy, “Sur deux nouveaux cas de modifications crâniennes observés à Paris,” Bulletins de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris 2, no. 3 (1868): 302, doi:10.3406/bmsap.1868.9540. L.-F.-C.-M. Moretin, “Crâne extraordinairement déformé trouvé à Voiteur (Jura),” Bulletins et mémoires de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris 5, no. 1 (1864): 383–84, doi:10.3406/bmsap.1864.6753, cited in Eric John Dingwall, Artificial Cranial Deformation: A Contribution to the Study of Ethnic Mutilations (London: J. Bale, Sons and Danielsson, 1931), 21–22.

[7] Dingwall, Artificial Cranial Deformation, 76.

[8] “Ce qui se fera avec des bandelettes que l’on a accoutumé de mettre, les conduisant petit à petit, sans beaucoup comprimer ny [ni] serrer, comme font quelques Nourrices: mais seulement faudra maintenir la teste avec mediocrité.” Jacques Guillemeau and Charles Guillemeau, De la grossesse et accouchement des femmes (Paris: A. Pacard, 1621), 771, ark:/12148/bpt6k5701564n, cited in Dingwall, Artificial Cranial Deformation, 58.

[9] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Émile, trans. Barbara Foxley (London: J. M. Dent and Sons, 1911), http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2256.

[10] See Jacques Ballexserd, Dissertation sur l’éducation physique des enfants (Paris: Vallat-la-Chapelle, 1762), 16–17, cited in Dingwall, Artificial Cranial Deformation, 61; Jean-François Icart, Leçons pratiques sur l’art des accouchements (Castres, France: P. G. de Robert, 1784), 169, ark:/74899/B315556101_FAC_001737, cited in Dingwall, Artificial Cranial Deformation, 61; and Olivier Stanislas Perrin, Galerie bretonne ou vie des bretons de l’Armorique (Paris: Isidore Pesron, 1835), 1:27, cited in Dingwall, Artificial Cranial Deformation, 61–62.

[11] Fernand Delisle, “Les modifications artificielles du crâne en France,” Bulletins de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris 5, no. 3 (1902): 119, doi:10.3406/bmsap.1902.6054.

[12] Although they were looking at asylums, many scientific studies have proven that artificial cranial modification does not cause any mental deficiencies.

[13] Léonard Freysselinard, La Tête limousine (Bordeaux, France: Cadoret, 1902), 37, cited in Dingwall, Artificial Cranial Deformation, 51.

[14] Achille Louis de Foville, Déformation du crâne résultant de la méthode la plus générale de couvrir la tête des enfants: Influence des vêtements sur nos organes (Paris: Mme Prévost-Crocius; J. Rouvier et C. Le Bouvier, 1834), 39–40, ark:/12148/bpt6k64481285, cited in Dingwall, Artificil Cranial Deformation, 47–48. For a more detailed summary of the statistics regarding cranial modification throughout France, see Dingwall’s chapter on later artificial cranial modification in Europe.

[15] I use the word deformation here because contemporaneous anthropologists designated these head shapes as such. However, I use the currently accepted “modification” in the rest of the article.

[16] The records concerning the artificially modified skulls currently in the Musée de l’Homme’s collection are limited. Many of these skulls were found while moving mass graves in Paris, so the identity of the deceased and their date of death is unknown. Other skulls were donated by anthropological societies or prominent anthropologists such as Paul Broca (1824–80), but little was recorded about who the deceased was or when he or she died. The Musée de l’Homme’s collection includes artificially modified skulls from many regions of France, including Hauts-de-France, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, Centre-Val de Loire, Occitanie, Nouvelle-Aquitaine, and Brittany. One of the artificially modified skulls donated by Broca is inscribed with the name, age, and birth place of the deceased—“Achille Cantier, 37 ans, (Tarn)”—which suggests that Broca may have collected the skull shortly after the death of the thirty-seven-year-old man. This is further supported by his presentation at the Anthropology Society of Paris on June 5, 1879. During the meeting, Broca presented the modified head of a man who had undergone an autopsy that morning “at the main hospital.” While discussing this skull, he brought up that another man with cranial modification—thirty-seven years old, from Tarn—had died that morning at the hospital. This suggests that the modified skull that was donated to the museum (Musée de l’Homme, #29080) was this same man who was born around 1842. See Paul Broca, “Crâne et cerveau d’un homme atteint de la déformation toulousaine” in Bulletins de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris 3, no. 2 (1879): 418, doi:10.3406/bmsap.1879.6297. While these bones are one remaining piece of evidence of this practice, the prominence of artificial cranial modification during the nineteenth century is more accurately established by the written records of medical personnel such as Achille Foville.

[17] Anacharsis Combes and Hippolyte Combes, Les Paysans français considérés sous le rapport historique, économique, agricole, médical et administratif (Paris: J. B. Baillière, 1853), 159, cited in Dingwall, Artificial Cranial Deformation, 62.

[18] François Mauriceau, The Accomplisht Midwife, trans. Hugh Chamberlen (London: J. Darby, 1673), 381, cited in Dingwall, Artificial Cranial Deformation, 59. Also, Adrien Bérenguier, Topographie physique, statistique et médicale du canton de Rabastens (Tarn) (Toulouse, France: A. Chauvin et Comp, 1850), 95, ark:/12148/bpt6k63702632, cited in Dingwall, Artificial Cranial Deformation, 52.

[19] The Trocadéro is one of a number of institutions and practices that is now regarded as racist in their attempt to demonstrate that the people conquered in distant lands were inherently inferior to Europeans. Other examples include the construction of indigenous villages in zoos throughout Europe and North America and the traveling villages of people from Africa and South America that were put on display during Universal Exhibitions. For more information, see Raymond Corbey, “Ethnographic Showcases, 1870–1930,” Cultural Anthropology 8, no. 3 (1993): 338–69; J. P. Daughton, An Empire Divided: Religion, Republicanism, and the Making of French Colonialism, 1880–1914 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006); Michael A. Osborne, Nature, the Exotic, and the Science of French Colonialism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994); Jan Pasler, “The Utility of Musical Instruments in the Racial and Colonial Agendas of Late Nineteenth-Century France,” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 129, no. 1 (2004): 24–76; Daniel J. Sherman, ed., Museums and Difference (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008); and Emmanuelle Sibeud, “A Useless Colonial Science? Practicing Anthropology in the French Colonial Empire, circa 1880–1960,” Current Anthropology 53, no. 5 (2012): 83–94.

[20] Sherman, Museums, 129.

[21] At the time, many anthropologists believed in polygenism, which argued that the different races of man arose independently and that the races were persistent and did not mix over time. Paul Broca, the founder of Paris’s anthropological society, called for research on living subjects in order to form a definitive hierarchy of races. For more, see Sibead, “A Useless Colonial Science?” Broca’s theories were not unique; other European scholars had been publishing about polygenism for decades. For more, see Anthea Callen, The Spectacular Body: Science, Method and Meaning in the Work of Degas (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995), 8–13.

[22] Faure, “Sordid Class,” 159–60. Faure’s figure is based on two separate studies that counted the number of ragpickers who entered the gates of the capital each day, factoring in the tonnage of garbage obtained.

[23] Faure, “Sordid Class,” 160–61.

[24] Faure, “Sordid Class,” 158.

[25] For a more detailed description of the various types of ragpickers working in Paris in the 1880s, see Ratcliffe, “Perceptions and Realities of the Urban Margin,” 211–15; and Faure, “Sordid Class,” 157–59.

[26] Émile de la Bédollière, Les Industriels, métiers et professions en France (Paris: Librairie de Mme Ve Louis Janet, 1842), 170. “Dès qu’il est armé Chiffonnier, dès qu’il s’est familiarisé à l’ignominie de ce sale métier, après l’avoir adopté par nécessité, il le continue par inclination. Il se complait dans sa vie nomade, dans ses promenades sans fin, dans son indépendance de lazarone. Il regarde avec un profond mépris les esclaves qui s’enferment du matin au soir dans un atelier, derrière un établi. Que d’autres, mécaniques vivantes, règlent l’emploi de leur temps sur la marche des horloges, lui, le Chiffonnier philosophe, travaille quand il veut, se repose quand il veut, sans souvenirs de la veille, sans soucis du lendemain. . . . Soumis à toutes les privations, le Chiffonnier est fier parce qu’il se croit libre.”

[27] Burton, Baudelaire and the Second Republic, 226.

[28] Two of the best-known examples of these reversals of fortune are found in works by Félix Pyat and Alexandre Privat d’Anglemont.

[29] Marnin Young, “Heroic Indolence: Jean-François Raffaëlli, The Absinthe Drinkers,” in Realism in the Age of Impressionism: Painting and the Politics of Time (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015), 157–58.

[30] Ratcliffe, “Perceptions and Realities of the Urban Margin,” 207–8.

[31] Raffaëlli regularly exhibited in the 1870s and 1880s and his work would have been on view at the Salon, in solo exhibitions, and in impressionist exhibitions. For more, see Young, Realism in the Age of Impressionism.

[32] Callen, The Spectacular Body, 5–6.

[33] Louis-Auguste Berthaud, “Les Chiffonniers,” in Français peints par eux-mêmes: Encyclopédie morale du XIXe siècle, vol. 3 (Paris: L. Curmer, 1941), http://www.bmlisieux.com/curiosa/berto02.htm.

[34] Privat d’Anglemont, Baudelaire, and Delvau, Paris, 51–52. “Le chiffonnier moderne, le sauvage de Paris . . . c’est le voyou insolent, sceptique, plus ignorant, plus crédule, aussi superstitieux, mais beaucoup plus méchant que le sauvage des grands lacs du Nord de l’Amérique.”

[35] Victor Fournel, Ce qu’on voit dans les rues de Paris (Paris: E. Dentu, 1867), 344, ark:/12148/bpt6k757298. “Les chiffonniers sont dédaigneux à l’égard du bourgeois: ils ne frayent qu’entre eux; ils forment une société à part, qui a des mœurs à elle, un langage à elle, un quartier à elle, auquel on peut à peine comparer les rues hideuses et méphitiques où grouillait acculée la population juive du moyen àge.”

[36] Victor Hippolyte de Luynes, Rapport sur les dépôts de chiffons (Paris: Imprimerie Chaix, 1886), 12, http://www.biusante.parisdescartes.fr/histmed/medica/cote?110141x125, cited in Faure, “Sordid Class,” 169–70.

[37] The ragpickers’ work was brought home with them as they sorted through the trash and stored it until they had more to sell.

[38] A. Boisard, Le Monde illustré, August 4, 1894, 75, ark:/12148/bpt6k63838032, cited in Faure, “Sordid Class,” 168. Translation by Lee Mitzman.

[39] The most notable written work on Clichy is Auguste-François Lecanu’s Histoire de Clichy-la-Garenne (Paris: Poussielgue, 1848), ark:/12148/bpt6k64499235.

[40] Adolphe Laurent Joanne, Les environs de Paris illustrés, 3rd ed. (Paris: Hachette, 1878), 2–4.

[41] Young, Realism in the Age of Impressionism, 142.

[42] Mary Anne Stevens, Émile Bernard 1868–1941: A Pioneer of Modern Art (Zwolle, Netherlands: Waanders Publishers, 1990), 133; Fred Leeman, Émile Bernard (1868–1941) (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 2013), 70.

[43] Stevens, Pioneer of Modern Art, 133.

[44] Leeman, Émile Bernard, 70.

[45] Ratcliffe, “Perceptions and Realities,” 218.

[46] The most notable exception is Raffaëlli, who included a female ragpicker in a number of scenes alongside a male counterpart.

[47] Gough, “French Workers and Their Wives in the Mid-Nineteenth Century,” 75. Proudhon and Michelet are two famous examples of men writing about the inferiority of women in the period, and rebuttals were published in the 1860s by Jenny d’Hericourt and Juliette Lamber, among others.

[48] This cloth is reminiscent of the type of bandeau that would have been used to create artificially modified skulls. However, it is highly unlikely that Bernard would have known about how heads were modified in this period.

[49] In the late nineteenth century, outsiders regarded the Breton costume as a medieval holdover. They saw the garments as both charming and extremely old fashioned. This was a misconception, as the Breton costume had emerged after the French Revolution. The abolition of sumptuary laws allowed the Bretons to develop the elaborate lace bonnets that became an iconic symbol of the region. For more, see Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, “Les Données bretonnantes: la prairie de la représentation,” in Modern Art and Modernism: A Critical Anthology, ed. Francis Frascina and Charles Harrison (New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1982).

[50] In Honoré de Balzac’s Les Chouans (1829), he writes, “the savage life and superstitious ideas of our rude ancestors still continue [in Brittany]. . . . The people were savages serving God and the King after the fashion of Red Indians.” Trans. by Katharine Prescott Wormeley (Project Gutenberg ebook, 2010), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1921/1921-h/1921-h.htm. The literature regarding Brittany and its perceived primitiveness is vast. See Elizabeth Emery and Laura Morowitz, Consuming the Past: The Medieval Revival in Fin-de-Siècle France (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2003); Caroline Ford, Creating the Nation in Provincial France: Religion and Political Identity in Brittany (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993); Sharif Gemie, Brittany, 1750–1950: The Invisible Nation (Cardiff, UK: University of Wales Press, 2007); Leslie Page Moch, The Pariahs of Yesterday: Breton Migrants in Paris (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012); Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, “Les Données bretonnantes,” 285–302; Michael Orwicz, “Criticism and Representations of Brittany in the Early Third Republic,” Art Journal 46, no. 4 (1987): 291–98; Eugen Weber, Peasants into Frenchmen: The Modernization of Rural France 1870–1914 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1976): part 1 and passim; Heather Williams, Postcolonial Brittany: Literature between Languages (Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang AG, 2007); Heather Williams, “Writing to Paris: Poets, Nobles, and Savages in Nineteenth Century Brittany,” French Studies 4 (2003): 475–90; and Patrick Young, Enacting Brittany: Tourism and Culture in Provincial France, 1871–1939 (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2012).

[51] Allison Morehead, Nature’s Experiments and the Search for Symbolist Form (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017).