The Early Collecting of Nineteenth-Century French Drawings at the Cleveland Museum of Art, 1914–34

by Britany SalsburyBritany Salsbury is associate curator of prints and drawings at the Cleveland Museum of Art and a specialist in nineteenth-century European works on paper. Her exhibitions and publications include Altered States: Etching in Late 19th-Century Paris (2016); and the forthcoming Nineteenth-Century French Drawings from the Cleveland Museum of Art (2023) and Degas and the Laundress: Women, Work, and Impressionism in Late 19th-Century Paris (2023). With Ruth E. Iskin, she coedited the book Collecting Prints, Posters, and Ephemera: Perspectives in a Global World (2019) and contributed a chapter on the collector and scholar Loys Delteil. Her dissertation on print portfolios in fin-de-siècle Paris, completed in 2015 at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, was supported by funding from the Getty Research Institute and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Email the author: BSalsbury[at]clevelandart.org

Citation: Britany Salsbury, “The Early Collecting of Nineteenth-Century French Drawings at the Cleveland Museum of Art, 1914–34,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 21, no. 2 (Summer 2022), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2022.21.2.6.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

The Cleveland Museum of Art (hereafter CMA) was one of several museums that opened to the public in urban centers across the United States during the early twentieth century and proceeded to build collections and recruit professionals to care for them. Scholarship has explored the growth of collections of nineteenth-century French art at museums throughout the country, but little is known about the place of drawings within these holdings during the early twentieth century, despite the fact that many museums in the United States began to acquire nineteenth-century French drawings early on.[1] This article examines the CMA’s early acquisitions of such works during its first two decades of collecting, focusing on several key examples as a means of surveying the considerations that informed the development of institutional collections in this field and the ways in which the market for drawings functioned at the time.

The CMA began to acquire drawings in 1915, just before its public opening in 1916 and shortly after other encyclopedic museums in the United States, including the Art Institute of Chicago and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, to name just two.[2] Acquired that year was Rosa Bonheur’s (1822–99) watercolor Sheep (fig. 1), the first nineteenth-century French drawing to enter the collection, through the estate of Hinman B. Hurlbut (1819–84)—a local philanthropist and businessman who created a purchase fund for the CMA upon his death in 1884 and bequeathed his own art holdings. Hurlbut was representative of a growing interest in nineteenth-century French art in the Midwest.[3] As was often the case, this early acquisition inspired the creation of a department for prints and drawings and the search for a curator. At the time, curators were often collectors themselves: wealthy men who had learned about drawings while building their own holdings.[4] At the CMA, the real estate investor Ralph Thrall King (1855–1926) was appointed the museum’s first volunteer curator of works on paper in 1919 (fig. 2). Like many museum professionals at the time, his mandate expanded beyond curatorial work to include building a collection and a department from scratch, and shaping the institution itself. King’s interest in then-contemporary art informed the museum’s early collecting; in one colleague’s words, he was “especially interested in fine drawings and believed that the Museum should make a determined effort to build up a representative collection in this field.”[5] He focused on building connections, visiting Joseph Durand-Ruel in his Parisian apartment and Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) in his studio.[6] King was passionate about modern French art and was praised for the fact that “his collection does not end with the Barbizon school, as does that of so many collectors and public institutions, but comes down bravely to our own day.”[7] It included drawings by artists including Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904), Alphonse Legros (1837–1911), Auguste Lepère (1849–1918), Édouard Manet (1832–83), and Odilon Redon (1840–1916), among others.

The CMA’s first professional curator of drawings was a graduate of Harvard’s newly formed Museum Course (1921–48), led by collector, financier, and associate director of the university’s Fogg Art Museum, Paul J. Sachs.[8] The course served as the primary training ground for future curatorial professionals. Sachs emphasized drawings throughout his program and, through the example of his own collecting interests and introductions to dealers in the field, encouraged a focus on nineteenth-century French works.[9] In 1922, the CMA hired Theodore Sizer (1892–1967), a military veteran and graduate of Harvard’s fine arts program (fig. 3).[10] Sizer’s correspondence reveals that he sought drawings during his frequent European travels to propose to local collectors and for the museum itself to acquire.[11] During his tenure, Sizer added to the collection of drawings by nineteenth-century French artists including Paul Gavarni (1804–66), Jean Louis Forain (1852–1931), Constantin Guys (1802–92), Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824–98), and Camille Pissarro (1831–1903). He argued for the didactic role of such works in the growing institution for educating the public about the work of recent artists.[12]

When Sizer left the museum to join Yale University’s history of art faculty in 1927, he was replaced by another Harvard fine arts program graduate, Henry Sayles Francis (1902–94) (fig. 4), who remained drawings curator for approximately forty years.[13] Having grown up alongside the collection of his uncle Henry Sayles (1834–1918), a renowned Boston collector of nineteenth-century French paintings, Francis accepted the position without ever having visited Cleveland.[14] He came from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which itself had begun to collect drawings early on. The year he arrived, Francis organized Master Drawings, an exhibition featuring works from public and private collections. Preparation for the exhibition allowed him to meet important dealers in the field and to familiarize himself with the holdings of works on paper at other newly established institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Morgan Library in New York, both of which served as lenders.[15] He continued to make professional connections through his European travels, using an allowance provided by the museum to gain familiarity with the drawings market. Together with then curator of paintings and future CMA director William M. Milliken (1889–1978), Francis conceived of a curatorial collection composed of fewer, carefully selected works, unlike many comparable institutions at the time, which were expanding their holdings through foundational gifts.[16] Making acquisitions that fulfilled such a standard of quality within the budget of a recently established institution required focused study of an increasingly complex drawings market and the establishment of strategic connections with dealers and collectors worldwide.

The CMA’s early purchases of drawings highlight how collecting and the market functioned in specific but representative ways. To make major acquisitions at attainable prices, for example, the CMA tried to anticipate the market. In 1925, the museum purchased Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s (1864–1901) Monsieur Boileau at the Café, a large portrait drawing (fig. 5). Featured in one of the first few exhibitions in the United States of Toulouse-Lautrec’s work, at Wildenstein & Co. in New York, and the first original work by the artist to be acquired by a museum in the United States, the purchase was speculative.[17] Although Toulouse-Lautrec’s reputation was established throughout Europe through solo exhibitions as early as the 1890s, he remained relatively unknown to US audiences, especially in the Midwest.[18] Sizer and Milliken seized on the artist’s obscurity to negotiate a discounted price.[19]

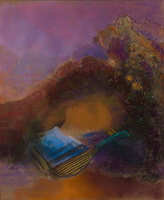

This tactic was viewed as a success and led to other strategic acquisitions, such as two pastels by Redon acquired, in Francis’s words, “before [the artist] was accepted anywhere.”[20] Milliken first viewed the artist’s work in its initial US exhibition in 1913 at the Armory Show in New York. He subsequently shared Redon’s drawings with King, who began to collect them, beginning with a watercolor of butterflies and flowers.[21] The two saw a major opportunity when the collection of John Quinn (1870–1924), an attorney and major early collector of modern French drawings, came up for auction at American Art Galleries in New York.[22] Quinn owned Redon’s pastel Orpheus, one of the most desired works in the sale (fig. 6). Based on the reception of that purchase, they bought Violette Heymann (fig. 7) within the same year, from New York’s Kraushaar Galleries, an established dealer of modern French art. The acquisitions led the international press to refer to Cleveland’s holdings by Redon as “more important than that of any other museum or even that of the Luxembourg galleries,” suggesting the perceived role of major, visible acquisitions in establishing US collections as equal in stature to those in France.[23]

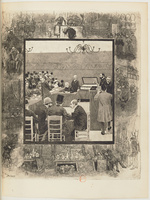

The CMA was one of a few museums in the United States able to acquire French drawings by traveling to bid at European auctions, a strategy that capitalized on the expansive European market and its low prices during the interwar years. In 1927, when late French senator Paul Bureau’s holdings of Honoré Daumier (1808–79) drawings—known to be the most important extant collection—appeared at auction, Sizer himself traveled to Paris to bid on Art Lovers (fig. 8).[24] Although museums typically purchased from dealers, rarely bypassing the middlemen, Sizer developed an interest in attending sales.[25] He described seeing dealers bid aggressively until the day’s close of sale, when they met to buy, sell, and exchange inventory among themselves.[26] This insularity was also reflected in the difficulty Sizer met in knowledgeably bidding at the Bureau sale, and he wrote of days spent obtaining an advance catalogue and attempting to preview available works.[27] There was a tense mood in the sales room—as seen in contemporary illustrations (fig. 9)—where, in Sizer’s words, an “iron ring” of Parisian dealers competed to build their own inventory for resale.[28] Sizer asked French dealer Marcel Guiot to accompany him, explaining that “you can’t walse [sic] into a Parisian sales room and beat these fellows at their own game.”[29] Bidding directly at the sale, the CMA obtained the drawing at a fraction of the usual price and without paying fees to a dealer or agent.

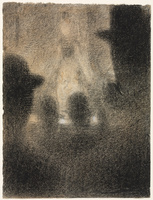

Many agents were active in the drawings market during the early twentieth century and assisted US museums with acquisitions. Such figures typically had prior gallery experience and independently purchased on behalf of Americans in the European market. Agents had considerable influence in advising clients, as they could choose which artists to promote, cultivate collectors, or steer interested buyers to purchases.[30] One of the CMA’s most frequently used agents was César de Hauke (1900–65), a former employee of dealer and gallerist Jacques Seligmann (1858–1923), who struck out independently to corner the market for modern French art. De Hauke offered the museum access to drawings that did not appear publicly on the market, such as a collection of fifty-seven portraits by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) that he marketed en bloc for $12,000.[31] De Hauke’s colleague and Seligmann’s son, Germain Seligman (1893–1978), also played a pivotal role in the distribution of George Seurat’s (1859–91) drawings throughout US museums. While researching his 1947 volume on Seurat’s drawings, Seligman compiled listings of works by the artist in private collections, bringing these works to the attention of institutions that sought examples of Seurat’s drawings; in 1945, for example, he wrote to Francis, who lamented that the artist was not represented in the CMA’s collection.[32] Seligman and de Hauke (who later authored Seurat’s catalogue raisonné) were able to share with the CMA a drawing from a private US collection uncovered during Seligman’s research, brokering its sale to the museum (fig. 10).[33]

De Hauke was one of several agents with whom the CMA worked throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Richard Owen (1873–1946) sought exemplary French drawings for the institution from European collections, writing to Francis in 1929, for example, to offer a sheet by Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805).[34] Dealer Harold Woodbury Parsons (1882–1967) influenced many collections in the United States and went so far as to advertise himself on his letterhead in 1932 as the “European Representative of the Cleveland Museum of Art.”[35] Martin Birnbaum (1878–1970), among the most active agents of the time, cultivated direct relationships with artists’ heirs in addition to European collectors, eventually working as an advisor for Grenville Winthrop (1864–1943), a connoisseur of nineteenth-century French art and an ardent Ingres enthusiast.[36] Although largely absent from art historical scholarship today, these figures played a crucial role in liaising between US institutions such as the CMA and a flourishing European drawings market.

Finally, the CMA made important early acquisitions by working with dealers to bring the drawings market to them. Throughout the 1920s, Sizer, Francis, and Milliken arranged a series of exhibitions aimed at educating the public about French paintings and drawings but also intended to motivate potential collectors by displaying works available for acquisition from galleries.[37] This practice was common among US museums at the time, with examples of exhibitions including the Museum of Modern Art’s Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, Van Gogh (1929), the Albright Art Gallery’s The Nineteenth Century: French Art in Retrospect, Eighteen Hundred to Nineteen Hundred (1932), and the California Palace of the Legion of Honor’s French Painting from the Fifteenth Century to the Present Day (1934).[38] These exhibitions had a particular impact beyond the East Coast, where dealers could reach entirely new audiences.

At the CMA, the exhibitions Fifty Years of French Art in 1926 (fig. 11) and French Art Since 1800 in 1929 both highlighted the field of nineteenth-century French drawings as accessible to collectors by featuring sheets from galleries such as Knoedler & Co., Durand-Ruel, Valentine, Kraushaar, Weyhe, and Wildenstein. Dealers contacted local collectors and incentivized purchases, and the museum acquired numerous works, such as Berthe Morisot’s (1841–95) Young Saint John (fig. 12) and Degas’s Before the Race (fig. 13), from these shows.[39] Francis later described the impact of the 1929 exhibition, writing that it “established a very good relationship with dealers . . . [and] promoted an active interest in the community.”[40] Purchases were made despite the onset of the Great Depression, with participating dealer F. Valentine Dudensing writing of his sales to Milliken in 1929 that he “[found] very little depression here with people who actually have wealth and are serious collectors.”[41] Correspondence between dealers and CMA curators reveals that members of the public sought works from the show and began to build their own collections of nineteenth-century French drawings.[42] The exhibitions also created public visibility for the CMA’s interest in nineteenth-century French drawings; following French Art Since 1800, for example, Berlin’s Galerie Thannhauser wrote the museum to offer further acquisition opportunities from its inventory, based on the checklist of included works.[43] The exhibition was considered such a success that the CMA and dealers themselves organized similar iterations in future years, generating enthusiasm for this field at the museum and the opportunity to introduce audiences to collecting.

These examples demonstrate some of the ways in which the CMA built a collection of nineteenth-century drawings by focusing on purchases early on. The museum drew on a confluence of factors to initiate a collection of nineteenth-century French works on paper that reflects the unique historical moment at which it was begun. Like many collecting institutions in the US, its holdings in this area have remained a cornerstone over the past century, encouraging a broader interest in the field that continues today.

Acknowledgments

This article is based upon the essay “Collecting Nineteenth-Century French Drawings at the Cleveland Museum of Art,” in Nineteenth-Century French Drawings, ed. Britany Salsbury, exh. cat. (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, forthcoming in 2023). I am grateful to Heather Lemonedes Brown, Jay A. Clarke, John Kelly, and Emily J. Peters for their feedback on that essay, and to Rachel Beamer and the staff of Giles Ltd. for their assistance.

Notes

[1] For just a few examples, see Monique Nonne and Richard R. Brettell, L’Impressionnisme, de France et d’Amérique, exh. cat. (Montpellier: Musée Fabre, 2007); Sylvie Patry, ed., Inventing Impressionism: Paul Durand-Ruel and the Modern Art Market, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery, 2015); and Claire Hendren, “French Impressionism in the United States’ Greater Midwest: The 1907–08 Traveling Exhibition,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 18, no. 1 (Spring 2019), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2019.18.1.3.

[2] The Art Institute of Chicago began to acquire prints and drawings by the French nineteenth-century artist Charles Meryon in 1909 and founded its Department of Prints and Drawings in 1911. See Suzanne Folds McCullagh, “Drawings in the Art Institute of Chicago,” Master Drawings 38, no. 3 (Autumn 2000): 241, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1554432 [login required]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York acquired nineteenth-century French drawings by artists such as Jehan Georges Vibert and Maurice Leloir as part of the bequest of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe in 1887. For an overview of this topic, see “Drawings in American Museums,” special issue, Master Drawings 38, no. 3 (Autumn 2000).

[3] As early as 1880, a published survey of American collections asserted that “the brilliant painters of the Paris exhibitions . . . have a fair showing in the city of Cleveland.” Edward Strahan, Art Treasures of America (Philadelphia: George Barrie, 1880), 67.

[4] On the demographics of early curators of works on paper, see Britany Salsbury, “Introduction, Part I: Collecting Modern and Contemporary Prints,” in Collecting Prints, Posters, and Ephemera: Perspectives in a Global World, ed. Ruth E. Iskin and Britany Salsbury (London: Bloomsbury, 2019), 18. The great exception to this trend in the curatorship of drawings was Agnes Mongan, one of the foremost early American experts on nineteenth-century French drawings. See Nicholas Fox Weber, “The Lover of Drawings,” in Patron Saints: Five Rebels Who Opened America to a New Art, 1928–1943 (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1992), 263–83.

[5] T.[heodore] S.[izer], “In Memoriam: Ralph Thrall King,” Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 13, no. 5 (May 1926): 97, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25136926.

[6] Nancy Coe, “The History of the Collecting of European Paintings and Drawings in the City of Cleveland” (master’s thesis, Oberlin College, 1955), xlv.

[7] S.[izer], “In Memoriam,” 96.

[8] On Sachs and the Museum Course, see Sally Anne Duncan and Andrew McClellan, The Art of Curating: Paul J. Sachs and the Museum Course at Harvard (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2018). I am grateful to Marjorie B. Cohn, Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Curator of Prints Emerita, Harvard Art Museums, for sharing her unpublished manuscript on this topic, “The Road Not Taken: Paul Sachs, Philip Hofer, and Museum Lives.”

[9] Henry Sayles Francis, oral history interview by Robert Brown, March 28, 1974–July 11, 1975, Archives of American Art (hereafter AAA), Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. For an overview of the scope of Sachs’s drawings collection, see Agnes Mongan, “Supplement: Check List of the Paul J. Sachs Collection,” in Works of Art from the Collection of Paul J. Sachs (1878–1965), exh. cat. (Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, 1965), 199–214.

[10] Sizer enlisted in the 27th Infantry Division in June 1917, following his graduation from Harvard University in 1915. Harvard College Class of 1916: Secretary’s Third Report (privately published, 1922), 413–14.

[11] Letter from Theodore Sizer to Leona Prasse, October 12, 1926, Theodore Sizer Papers, Records of the Prints and Drawings Department, Cleveland Museum of Art Archives (hereafter CMA Archives), Cleveland, OH.

[12] Sizer did so primarily through articles published in the CMA’s Bulletin. See, for example, T.[heodore] S.[izer], “An Exhibition of Drawings,” Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 11, no. 7 (July 1924): 140–41, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25136780.

[13] Francis left the CMA in 1929 to take Paul J. Sachs’s Museum Course at Harvard University and work at the Fogg Art Museum, but he was recruited back to Cleveland in 1931 with the promise of an expanded position.

[14] Francis, oral history interview.

[15] Francis, oral history interview.

[16] See letter from William Milliken to Paul J. Sachs, January 24, 1951, box 7, folder 4, William Milliken Papers, CMA Archives; and letter from Henry Sayles Francis to Paul J. Sachs, January 10, 1951, box 29, folder 582, Paul J. Sachs papers, Harvard Art Museums Archives, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

[17] This acquisition is discussed in greater depth in Heather Lemonedes Brown, “Monsieur Boileau at the Café,” in Nineteenth-Century French Drawings, ed. Britany Salsbury, exh. cat. (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, forthcoming in 2023).

[18] For example, the exhibition Portraits and Other Works by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec took place at London’s Goupil Gallery in May 1898. His work was first shown in the United States over a decade later, in the 1909 exhibition Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec at New York’s Photo-Secession Gallery and then in 1914 at Wildenstein & Co.’s Exhibition Toulouse-Lautrec in New York. For a full chronology, see Anne Roquebert, “Exhibitions,” in Toulouse-Lautrec, exh. cat. (London: Hayward Gallery, 1991), 545–47.

[19] The price was discounted in part because the purchase was accompanied by the deaccession and resale to Wildenstein of four minor paintings from the CMA’s collection. William M. Milliken, “Cleveland Museum of Art Collections,” unpublished typewritten memoir (1960), box 50, folders 1–6, William Milliken Papers, 46, CMA Archives. Commenting in this memoir on the market’s expansion in the years after 1925, Milliken described the purchase as one that could only have been made at that particular moment, writing that “prices were amazingly modest in comparison with . . . today. . . . It was truly B.S., [or] before Sotheby’s.”

[20] Francis, oral history interview.

[21] Milliken, “Cleveland Museum of Art Collection.” This particular drawing was not one of King’s eventual gifts to the CMA and its whereabouts are unknown today. For similar works, see Alec Wildenstein, Odilon Redon: catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint et dessiné, vol. 3 (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 1996), 22–23.

[22] On Quinn’s collecting, see Judith Zilczer, “The Noble Buyer”: John Quinn, Patron of the Avant-Garde, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, 1978).

[23] “Cleveland’s New Redon,” Art Digest, January 1, 1927, 12.

[24] The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which had also established a practice of bidding at European sales, likewise acquired a Daumier watercolor at this auction. Then curator of prints William Ivins acquired Street Show (Paillasse) (ca. 1865–73), a work that Sizer admired but felt was “so sketchy, that it will be passed by the public I am sure.” Letter from Theodore Sizer to Frederic Allen Whiting, May 24, 1927, Theodore Sizer Papers, Records of the Prints and Drawings Department, CMA Archives.

[25] Dealer Victor D. Spark described this phenomenon: “[Museums] didn’t go to auctions except on rare occasions. And the difference between the retail price and what you’d get it for at auction was enormous—enormous.” Victor D. Spark, oral history interview by Paul Cummings, August 5, 1975, AAA, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

[26] Letter from Theodore Sizer to Leona Prasse, November 16, 1926, Theodore Sizer Papers, Records of the Prints and Drawings Department, CMA Archives.

[27] Letter from Sizer to Whiting, May 24, 1927. Germain Seligman also described the challenges of bidding, even for dealers; auctions were often haphazardly organized and works had to be examined quickly since too much attention would draw the attention of other preview attendees. See Germain Seligman, Merchants of Art: 1880–1960, Eighty Years of Professional Collecting (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1961), 1–2.

[28] Sizer described the auction room as filled with curators from the Musée du Louvre in Paris and French provincial museums, alongside representatives from Knoedler & Co., Kraushaar Galleries, and “half the dealer world that [I] know so well.” Letter from Sizer to Whiting, May 24, 1927.

[29] Letter from Sizer to Whiting, May 24, 1927.

[30] Sébastien Chauffour, “Selling French Modern Art on the American Market: César de Hauke as Agent of Jacques Seligmann & Co., 1925–1940,” in Dealing Art on Both Sides of the Atlantic, 1860–1940, ed. Lynn Catterson (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 227.

[31] Letter from César de Hauke to Leona E. Prasse, December 20, 1926, box 399, folder 14, Jacques Seligmann & Co. Records, AAA, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Cleveland collector Henry G. Dalton acquired a sheet from this group, which later came to the museum. The drawing, which is still in the museum’s collection, is now considered to be after Ingres: Charles Thévenin, ca. 1817, graphite on paper, 30.2 x 25.4 cm, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund, 1943.387.

[32] Letter from Henry Sayles Francis to Germain Seligman, December 4, 1945, box 446, folder 8, Jacques Seligmann & Co. Records, AAA, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

[33] See typescript list of Seurat drawings in the United States, ca. 1947, box 446, folder 9, Jacques Seligmann & Co. records, AAA, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

[34] In the same letter, Owen described his role as “to let [the museum] know at any time when I had bought a drawing that I believe would be suitable . . . and worthy.” Letter from Richard Owen to Henry Sayles Francis, January 30, 1929, CMA Archives. On Owen’s activities, see Danielle Hampton Cullen’s article “The Elusive Mr. Richard Owen: A Dealer’s Rise and Fall in the American Art Market” in this issue: https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2022.21.2.5.

[35] Letter from Harold Woodbury Parsons to Henry Sayles Francis, January 1, 1932, CMA Archives.

[36] Marjorie B. Cohn and Susan L. Siegfried, Works by J.-A.-D. Ingres in the Collection of the Fogg Art Museum (Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, 1980), 11.

[37] In addition to exhibitions organized by and/or held in museum galleries, dealers also arranged exhibitions of their own. In 1927, for example, de Hauke wrote to Milliken about a show of contemporary paintings that he would have on display at Cleveland’s Gage Gallery of Fine Arts, featuring works by Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), Gustave Courbet (1819–77), Manet, Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), and Edouard Vuillard (1868–1940), among others. Letter from César de Hauke to William Milliken, March 11, 1927, box 399, folder 14, Jacques Seligmann & Co. Records, AAA, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

[38] See Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, Van Gogh, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1929); Catalogue of the Exhibition of Nineteenth Century French Art, exh. cat. (Buffalo, NY: Albright Art Gallery, 1932); and Exhibition of French Painting from the Fifteenth Century to the Present Day, exh. cat. (San Francisco: California Palace of the Legion of Honor, 1934).

[39] These connections were sometimes indirect. For example, William Milliken wrote to John J. Cunningham Jr. of Knoedler & Co. to ask whether his inventory included any landscapes by Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), on behalf of a local collector who was taken by an example in French Art Since 1800 that was not for sale. Letter from William M. Milliken to John J. Cunningham Jr., November 13, 1929, box 3, folder 4, Exhibition Compendium, CMA Archives.

[40] Francis, oral history interview.

[41] Letter from F. Valentine Dudensing to William Milliken, November 21, 1929, box 3, folder 4, Exhibition Compendium, CMA Archives.

[42] For a full list of purchases, see “Sales–French Art Since Eighteen Hundred,” box 3, folder 4, Exhibition Compendium, CMA Archives.

[43] Letter from Galerie Thannhauser to Cleveland Museum of Art, January 10, 1930, box 3, folder 4, Exhibition Compendium, CMA Archives.