Learning to Draw Landscape in Nineteenth-Century France

by Patricia MainardiPatricia Mainardi is professor emerita of art history at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. In addition to many articles, catalogues, and reviews, her publications include Art and Politics of the Second Empire, which received the 1988 College Art Association Distinguished Book Award; The End of the Salon: Art and the State in the Early French Republic (1993); Husbands, Wives and Lovers: Marriage and Its Discontents in Nineteenth-Century France (2003); and Another World: Nineteenth-Century Illustrated Print Culture (2018). She has received numerous fellowships, including from the National Endowment for the Humanities, CASVA, the Institute for Advanced Study, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Council of Learned Societies, the Yale Center for British Art, and the Institut national d’histoire de l’art. In 2014 she was appointed Chevalier in the French Ordre des palmes académiques, and, in 2017, she received the CAA Distinguished Teaching of Art History Award. Her current research project treats the pedagogy of nineteenth-century landscape drawing and painting.

Email the author: pmmainardi[at]gmail.com

Citation: Patricia Mainardi, “Learning to Draw Landscape in Nineteenth-Century France,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 21, no. 2 (Summer 2022), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2022.21.2.2.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Landscape drawing was not taught in French art schools, although by the later eighteenth century it had been introduced into the curricula of northern countries that were less in the thrall of classicism.[1] In France, however, landscape ranked low in the hierarchy of subjects, below history painting and even genre, higher only than still life. The French Academy recommended only that artists stroll through nature with a small sketchbook as relaxation from their more arduous labors.[2] And yet despite this, landscape became a major category of art, to the point where the Goncourt brothers could write of the first French Exposition Universelle in 1855: “Landscape is the victory of modern art. It is the honor of the nineteenth century.”[3]

So how did students learn to depict landscape? There seems to be a great gap in our historiography; we are told only that students copied paintings or that they worked directly from nature.[4] Figure drawing, on the other hand, had a clearly established pedagogy that dated back centuries. Students began by copying prints of ideal facial features of antique sculpture, then prints after the entire sculpture; next they drew from the sculpture itself (or at least a cast of it), until, finally, they were allowed to draw from live models who often adopted the very same poses. They then combined these fragments and sketches to create finished paintings.[5] Painters of various persuasions used this additive method throughout their careers, often maintaining a stock of drawings for later reference. Artists as different as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) and Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) and Georges Seurat (1859–91), all made numerous drawn and painted studies that they “collaged” together into ambitious paintings. Because of this exclusive focus on the figure, in earlier periods, artists tended to specialize, so a figure painter often entrusted the landscape and animals to a specialist, and a landscape painter did the same with the figures. With the rising status of the artist as unique creator in the nineteenth century, however, it became incumbent on one artist to complete the entire painting. I propose that drawing manuals helped them to do this.

Landscape drawing was a necessary skill long prized by engineers, architects, and the military, who needed accurate knowledge of the topography of the terrain. And yet, although artists had long made drawings and prints that their students and apprentices would copy, I have not found landscape drawing manuals from earlier than the eighteenth century, although figure manuals existed from medieval times.[6] Abraham Bosse’s (1604–76) seventeenth-century treatise, published posthumously as Collection of Plates for Learning to Draw without a Master, Portrait, Figure, History, and Landscape, did include landscape but only in order to demonstrate the principles of surveying.[7] This is apparent in his Method of Establishing the Different or Equal Heights of Two Towers by Using a Level (fig. 1). Despite this, the French École Polytechnique, established in 1794 to train the nation’s military officers and engineers, taught landscape drawing based exclusively on copying antique figure sculpture. Its first instructor of drawing, Citizen Neveu, defended the practice, stating, “This study is the key to all arts based on drawing; it leads to the different kinds of drawings necessary to the engineer, like architecture, landscape, mapmaking, etc. It teaches how to estimate proportions and express them accurately, to install, so to speak, a compass in the eye.”[8]

The treatise of Charles-Antoine Jombert (1712–84), first published in 1740 and reissued later, was, if not the first, then certainly one of the earliest to include landscape images for themselves alone. And yet his title reveals the low status of the genre, with landscape ranking last, after even animals: Method of Learning to Draw Wherein Are Given the General Rules of This Great Art, and the Precepts for Learning and Perfecting It in Very Little Time, Enriched with a Hundred Plates Representing Different Parts of the Human Body after Raphael and Other Great Masters, Several Academic Figures Drawn from Nature by M. Cochin, the Proportions and Dimensions of the Most Beautiful Antique Sculpture Seen in Italy, and Some Studies of Animals and of Landscapes.[9] Even Pierre Henri de Valenciennes’s (1750–1819) much-cited treatise of 1799, Elements of Practical Perspective for Artists, Followed by Reflections and Advice for a Student on Painting and Particularly on Landscape, primarily treated perspective, with landscape added only as the secondary subject.[10] Valenciennes included illustrations only for the perspective section of his book, and Jombert—like Bosse before him—included only complete landscape views, although both extensively analyzed figure drawing through graduated modules of eyes, noses, heads, and limbs. One of Jombert’s few landscapes attests to the necessity of an in-depth study of how the disparate elements of landscape should be combined (fig. 2). It features the totally improbable combination of a rhinoceros—a jungle beast—juxtaposed with a camel—a desert beast—situated among alpine cliffs and fir trees where neither animal would ever reside. When the disparate elements do not function together, we can best see the synthetic aspects of these images. Despite this paucity of landscape images, Jombert wrote, “one of the greatest faults of landscape artists is that, once they have adopted a leaf style that satisfies them, they use it to represent all sorts of trees. . . . Each kind of tree has a particular manner of growing its branches; and its sprays of leaves have a form particular to each one.”[11] To correct this problem, Jombert advises the same system of instruction as for figure painting, first copying prints, then drawings, then paintings, and only then consulting nature, once its configurations are already well known.[12]

This pedagogical method was repeated even by Valenciennes, whose advice to work from nature was so well-known that the impressionist Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) sent a copy of Valenciennes’s treatise to his son.[13] But Valenciennes’s preliminary advice that students should begin by copying printed imagery before venturing forth to confront nature seems to have been overlooked by art historians, although he wrote clearly enough: “Our student for several months has drawn under our supervision; he has copied the work of the best masters, but he has not viewed nature.”[14] His oft-repeated advice to go out into the landscape and depict what one sees was actually the second stage of his landscape pedagogy, to be preceded by an initial stage of copying.

Internet Archive.

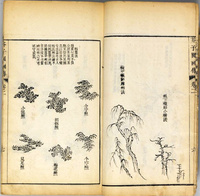

Here we must take a brief detour from the landscape of Europe to go halfway around the world to China, where the Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting was first published in 1679 in woodblock prints and then reprinted constantly, proving essential to both Chinese and Japanese artists (fig. 3).[15] Since numerous copies have long existed in European collections, it is entirely possible that this type of landscape instruction, the systematic progression of modules from leaf to landscape characteristic of nineteenth-century drawing manuals, was developed first in China.

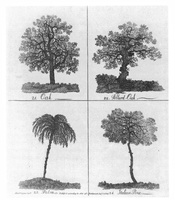

By the later decades of the eighteenth century, landscape pedagogy was being developed in Europe. In 1771, Alexander Cozens (1717–86) produced a portfolio entitled The Shape, Skeleton, and Foliage of Thirty-Two Species of Trees for the Use of Painting and Drawing, in which his images greatly resembled botanical illustrations that depicted the entire tree in schematic form but with no setting (fig. 4).[16] Three years later the French engraver Jean-François Janinet (1752–1814) and the painter Jean Philippe Sarazin (d. ca. 1795) together began producing their series of landscape portfolios analyzing trees in modules of leaf, branch, and trunk (fig. 5).[17] Cozens took a different approach in A New Method of Assisting the Invention in Drawing Original Compositions of Landscape (ca. 1785), in which he laid out his “blot” method of composition, focusing less on individual species than on overall effect (fig. 6).[18] It wasn’t until 1804, however, when Alphonse Nicolas-Michel Mandevare (ca. 1770–ca. 1850), a student of Valenciennes, published Analytic Principles of Landscape for the Use of Schools in the Departments of the French Empire, that landscape pedagogy began to develop truly parallel to figure study.[19] Valenciennes had written that the student of landscape needed to study four aspects of a tree: the form of the trunk; the disposition of the branches; and the arrangements of the leaves and of their masses.[20] Following this dictum, Mandevare broke down the subject into stages, beginning with simple geometric shapes and progressing through leaf, branch, and tree, to rock and terrain (figs. 7–12).

by the author.

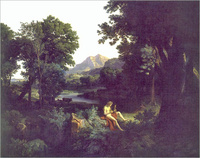

It was largely through the influence of Valenciennes that the French Academy established a Prix de Rome for classical landscape (paysage historique), alongside its more prestigious Prix de Rome for history painting.[21] In this way it both recognized that landscape painting had become an increasingly important category of art and encouraged its development. Landscape was still considered secondary, however, for the prize was given only every four years instead of annually like the Prix de Rome for history painting. The first landscape prize in 1817 was given to Valenciennes’s student Achille Etna Michallon (1796–1822) for his Democritus and the Abderites (fig. 13); it was subsequently awarded every four years until 1861, when it was abolished amid the 1863 reforms of the École des Beaux-Arts.[22]

Competitors for the landscape Prix de Rome had to compete in three stages. The first was a historical landscape sketch on a subject from history, mythology, or religion, determined by the painting section of the Academy and executed in one day. In the second competition, students had six days to paint a “tree portrait,” the species to be announced on the first morning by the professor in charge. Finally, competitors had to create a finished painting on the given historical, mythological, or religious theme, in which the landscape dominated the figures. Students were judged not only on their composition, drawing, and painting but also on their botanical acumen: they were expected to include at least three different tree species in their competition painting.[23] In 1825, André Giroux (1801–79) won the prize with The Hunt of Meleager (fig. 14). The source for this story, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, describes the event as taking place in a dense wood beneath a mighty oak, and Giroux was clearly attentive to that imperative.[24] The laurel was sacred to Apollo, so Eugène-Ferdinand Buttura (1812–52) carefully delineated the leaves of that tree in his Apollo Tending the Flocks of Admetus, which won the 1837 prize (fig. 15).[25]

This award certainly did acknowledge and encourage the production of landscape as a respected category of French art. But how did young artists learn the configurations of the various trees? This would have been especially challenging since French academic instruction took place in the studio. In the wake of Valenciennes’s treatise, Mandevare’s manual, and the establishment of the Prix de Rome for historical landscape, the market was soon flooded with landscape-drawing manuals with titles such as Studies after Nature for Young Landscapists, Progressive Sketches of Landscape after Nature, and Studies of Trees, to cite just a few.[26] Most were authored by established landscape artists seeking to extend their audience as well as to instruct their students.

Throughout landscape instruction, the principle persisted that the tree in its isolated glory was symbolic of the human body, and so the tree portrait competition for the landscape Prix de Rome must be understood as parallel to the full-length nude figure studies that were so basic to academic art instruction. Academic training required students to first draw the figure nude, then clothed, in order to understand the body’s essential structure. Jacques-Louis David’s (1748–1825) preparatory drawing of models in the buff for his Oath of the Tennis Court (1790–92) well illustrates this practice (figs. 16, 17). Following the same principle in landscape, Mandevare first drew the tree’s skeleton “naked” in “Oak Tree Stripped of Foliage,” and then showed it “clothed” in leaves (figs. 18, 19). These drawings follow the principle laid down by Valenciennes: “To understand the form of a tree and its branches, you must draw it in winter, when it has lost its leaves; then its skeleton can be understood as well as its entire structure.”[27]

Musée Carnavalet.

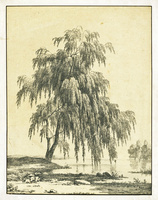

All Prix de Rome contestants had to know the numerous tales from religion, mythology, and history that might be assigned in the principal competition, but contestants in historical landscape also had to know the species of trees featured in each of those tales.[28] Central to the concept of the historical landscape was the necessity of matching the landscape setting to the story depicted in order to avoid errors like Jombert’s. As a result, landscape drawing manuals devoted sections to each of the major species of tree. Students had to know that the laurel tree was sacred to Apollo, the linden to Venus. Zeus was always represented by an oak, usually an aged and gnarly specimen. The sign of Bacchus was, of course, the vine. The cypress represented the underworld, the weeping willow sadness and melancholy. But the beech was always the happy tree, representing sweetness, joy, and vitality; we see it so often in landscape paintings that it seems to have become generic (fig. 20).

It is unfortunate that the competition tree portraits have not been preserved, but their progeny contribute to the history of nineteenth-century art. Gustave Courbet (1819–77) painted several tree portraits, despite his antagonism to all things academic; his Oak of Flagey, or The Vercingétorix Oak (1864) is a portrait of a famous local tree identified with the early Gallic king (fig. 21). Photographers like Gustave Le Gray (1820–84) documented the most famous trees in the Forest of Fontainebleau (fig. 22), and Claude Monet (1840–1926), with his Bodmer Oak, Forest of Fontainebleau (1865), paid homage to Karl Bodmer (1809–93), whose painting of an ancient oak in the forest had been exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1850 (figs. 23, 24).

By the 1830s, the new art-buying and art-viewing public preferred recognizable scenes to the feats of the gods; more informal views from nature now competed with historical landscape painting. There was a new interest in genre subjects, what an earlier age had dismissed as mere staffage and often left to a collaborator. Although academic art instruction still taught the figure and its poses based only on classical models, now artists wanted to animer le paysage, to enliven the landscape through the addition of genre vignettes that replaced the gods and heroes of the paysage historique.[29] The results of this new imperative can be seen in a comparison of Camille Corot’s (1796–1875) preparatory study for The Bridge at Narni with the finished work, to which he added vignettes of rural figures (fig. 25, 26). In Under the Birches (Le Curé), Théodore Rousseau (1812–67) included the vignette of a priest reading, a genre subject that neither Mandevare nor his followers had deigned to include in their manuals (fig. 27). Meeting this new interest, well-known illustrators published albums of such scenes for the use of amateur as well as professional artists, but increasingly in attractive formats that would appeal to a general audience as well. Here the British definitely took precedence; William Henry Pyne’s (1769–1843) publication, Microcosm: or a Picturesque Delineation of the Arts, Agriculture, Manufactures, &c. of Great Britain, in a Series of above Six Hundred Groups of Small Figures for the Embellishment of Landscape (1802–6) inspired numerous imitators on both sides of the Channel; like most ambitious publications, it appeared first in installments and only later as bound volumes (fig. 28).[30] In France, lithography encouraged the proliferation of inexpensive albums of such images, with titles such as François Fortuné Antoine Férogio’s (1805–88) Progressive Studies of Picturesque Figures for Landscape Artists (1839) (fig. 29).[31] The well-known illustrator Victor Adam (1801–66) published several albums of such vignettes, often issued simultaneously in London and Paris; his New Year’s Gifts for Landscape Artists (1832) was advertised as “twenty-four studies of animals designed to be used as models for students and as motifs for landscape painters to enliven their pictures.”[32] Albums such as these, often sold as loose sheets as well, helped artists to complete paintings begun out-of-doors but later completed in the studio. While some of these publications continued the step-by-step drawing instruction that Mandevare had initiated, most did not; instead, their vignettes were presented as complete drawings in order to appeal to a broader market. In this way these publications contributed to the creation of the new hybrid genre of the lithographed sketchbook, precursor of the coffee-table art book of a subsequent age.[33]

This transformation from pedagogical tool to picturesque album can be seen in the publications of the publisher Charles Philipon (1800–1861). In 1832 he wrote to the artist Achille Devéria (1800–1857):

Times are difficult (as you have no doubt heard) and the public, which always imitates the king, becomes stingier by the day; for them to spend a penny, you have to give them gold. So, I’ve had my brother-in-law [Gabriel Aubert] publish some little medleys which, on a single sheet, contain twenty or twenty-four little images. It’s just merchandise, I agree, but it’s the only thing that’s selling and Aubert calls them masterpieces.[34]

Devéria, as well as Adam, Paul Gavarni (1804–66), Grandville (Jean-Isidore Gérard, 1803–47), Traviès (Charles Joseph Traviès de Villers, 1804–59), and many other contemporary artists and illustrators, might not have thought these were masterpieces, but they did not object to earning a little ready cash, and so we find numerous artists contributing to this new genre.

In the 1832 prospectus for his new journal Le Charivari, Philipon advertised these medleys, known as macédoines, or fruit salads. Aubert’s Little Medleys (Petites macédoines d’Aubert), as they were called, were marketed as

a collection of around a hundred plates of pretty little drawings in all genres, in all styles, and in all sizes. These drawings, combined in sometimes infinite number on a single sheet that sells for only one franc, are intended for all manner of decoration and artwork. They can be cut out, traced, colored, glued onto boxes or screens, used as little bookmarks, [or] as little models for learning to sketch. Colored with taste they can be used to create albums which perfectly resemble watercolor. The sheets are sold separately. Every artist known and loved by the public can be found here; each has made at least one sheet, some have made several.[35]

They obviously sold well because three years later Philipon’s macédoine collection was advertised as now encompassing 250 prints; other publishers joined the fray, producing untold numbers of these sheets.[36] Their audience was not limited to the students and artists of earlier periods, but now also comprised those who would use them for the type of handiwork once reserved for the leisured classes, what the French call découpage, namely cut-and-paste craft and decorative art projects.[37] Perhaps their largest audience, however, was composed of those who simply admired them and enjoyed leafing through the albums for pleasure.

It didn’t take long before these medleys became themselves playful works of art. Such prints often were republished with no mention of their previous pedagogic purpose, although they continued to be advertised as drawing aids. Férogio, like many artists, published the same sheet in a variety of formats, sometimes as a model for drawing, sometimes (minus the didactic title) as a purported sketchbook page (fig. 29). The artist Nicolas-Toussaint Charlet (1792–1845) worked both markets superbly. When he assumed the post of drawing professor at the École Polytechnique in 1839 and discovered that young engineers and military officers were still taught drawing only by copying antique figure sculpture, he quickly revised the curriculum. He produced his own landscape drawing manual, Set of Ink Drawings for the Use of Students in the Specialized Schools of Bridges and Roads of Metz, Military Personnel, and Others, all the while continuing to produce lithographs and sheets of macédoines for a broader market (figs. 30, 31).[38] The vignettes these artists offered seem to close the circle with contemporaneous painting, both inspiring it and being inspired by it.

by the author.

While it seems obvious that such images were used by students and amateur artists, I think it is probable that all landscape artists made some use of them, at least in their formative years. Corot, for example, is known to have copied the drawings of Michallon, his first master, who had published a portfolio of landscape drawings.[39] After Michallon’s death in 1822, Corot spent three years as a student of Michallon’s master, Jean Victor Bertin (1767–1842), himself a student of Valenciennes and then the preeminent painter of historical landscapes; there Corot copied the drawings of Mandevare as well as those of Bertin himself, who also had published a portfolio of landscape drawings for students (fig. 32).[40] When Corot completed his Bridge at Narni (see fig. 26), besides adding the figural vignettes, he also included a stone pine that was not present in his painted sketch (see fig. 25) but that greatly resembles Mandevare’s model (fig. 33). This species was so emblematic of the Italian landscape that Corot even included it in his Italian Landscape of 1835 (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles), painted in Paris, and Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851) added it into his paintings even before he had ever journeyed to Italy.[41] Rousseau was a student of Charles Rémond (1795–1875), who had also been a student of Valenciennes. In 1821, Rémond won the landscape Prix de Rome with his Proserpine Carried Off by Pluto (fig. 34).[42] He then published two major portfolios of landscape studies, Principles of Landscape and Complete Landscape Course, that he had his students copy.[43] Despite Rousseau’s disavowals, Rémond’s Trunks of Birch Trees (fig. 35), when seen alongside Rousseau’s Under the Birches (see fig. 27) demonstrates his influence.

I am not suggesting that these artists copied these drawings, but only that all landscape painters learned to conceptualize nature through drawings such as these, in much the same way that students at the École learned to draw the figure by copying engravings and casts. In the architect Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc’s (1814–79) fictionalized Story of a Draftsman, How One Learns to Draw, he answers the criticism that students were forced to copy prints instead of nature by explaining, “It is necessary to draw from graphic models first, in order to learn how to conceptualize nature.”[44] Closer to our own time, Ernst Gombrich, in his classic study Art and Illusion, argued that we see only through our cultural expectations, and that there is no such thing as an innocent eye. He recounts the story of taking a group of Chinese art students trained in different visual conventions on a nature-sketching expedition. They were so baffled by the unfamiliar conventions that they asked for something to copy that would help them to visualize it.[45] That is the purpose that these drawing manuals served.

By the time that the Prix de Rome for historical landscape was abandoned in 1863, the school of naturalist landscape painting was ascendant. New landscape drawing manuals continued to be published, however, and many earlier ones were reprinted as well.[46] And, while the importance of individual tree species as an integral part of history painting had receded, along with that category itself, trees took on new significance as carriers of form: Paul Cézanne’s (1839–1906) architectonic pine trees, Vincent van Gogh’s (1853–90) tortured cypresses, Monet’s decorative poplars.[47] The visual character of each species became even more important once its literary narrative element had been discarded. And so, when we look at landscape drawings, we should keep in mind these drawing manuals, humble pedagogic tools that served generations of landscape painters who were just learning how to depict leaf, branch, and tree, but who would, in later years, insist that they had no master other than nature.

Acknowledgments

Aspects of this research were presented at the 2018 College Art Association session “Collecting, Cutting, and Collaging” that Cynthia Roman and I cochaired; the Dahesh Museum of Art in 2018; the Yale University Workshop on Topography in 2019; and the 2021 Cleveland Museum of Art symposium “From Creation to Collection: Making and Marketing Drawings in 19th-Century France.” I thank Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, Asher Miller, Cynthia Roman, and Britany Salsbury for many valuable discussions on the subject, especially Britany Salsbury for the opportunity to publish this essay.

Notes

All translations are by the author.

[1] The subject was regularly taught in academies in Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Scandinavia, and the Low Countries; see Nicolas Pevsner, Academies of Art, Past and Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1940; New York: DaCapo, 1973), 232–35.

[2] For a discussion of the eighteenth-century French Academy’s attitude towards landscape, see Emmanuelle Brugerolles, “La Pratique du plein air dans l’enseignement académique,” in Dessiner en plein air: Variations du dessin sur nature dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle, ed. Marie-Pierre Salé, exh. cat. (Paris: Lienart, 2017), 51–57.

[3] “Le paysage est la victoire de l’art moderne. Il est l’honneur de la peinture du dix-neuvième siècle.” Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, La Peinture à l’Exposition Universelle de 1855 (Paris: E. Dentu, 1855), 18.

[4] Jeremy Strick was the first to deal with this subject, although he came to very different conclusions from mine; see his “Connaissance, classification et sympathie: Les cours de paysage et la peinture du paysage au XIXe siècle,” Littérature, no. 61 (1986): 17–33, http://www.persee.fr/.

[5] On academic drawing pedagogy, see Albert Boime, The Academy and French Painting in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Phaidon, 1971), 24–36.

[6] Numerous early drawing manuals are catalogued and digitized at https://www.arthistoricum.net/.

[7] Abraham Bosse, Recueil de figures pour apprendre à dessiner sans maître, le portrait, la figure, l’histoire et le paysage (Paris: C. A. Jombert, 1732).

[8] “Cette étude est la clef de tous les arts qui ont le dessin pour base; elle conduit aux différens genres de dessins nécessaires à l’ingénieur, tels que l’architecture, le paysage, la carte, &c. Elle accoutume à estimer les proportions, à les exprimer avec justesse, à se mettre, comme on dit, le compas dans l’oeil.” Citoyen [François-Marie] Neveu, “Compte rendu par l’Instituteur du Dessin, relativement à cette partie de l’enseignement,” Journal polytechnique, ou Bulletin du travail fait à l’école centrale des travaux publics, publié par le conseil d’instruction et administration de cette école (Paris: Imprimerie de la République, Germinal, an 3 [1794]), premier cahier, 78–80.

[9] Charles-Antoine Jombert, Méthode pour apprendre le dessein, où l’on donne les règles générales de ce grand art, & des préceptes pour en acquérir la connoissance, & s’y perfectionner en peu de temps: enrichie de cent planches représentant différentes parties du corps humain d’après Raphaël & les autres grands maîtres; plusieurs figures académiques dessinées d’après nature par M. Cochin; les proportions et les mesures des plus beaux antiques qui se voient en Italie, & quelques études d’animaux et de paysage (Paris: l’auteur, 1755), https://gallica.bnf.fr/.

[10] Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, Élémens de perspective pratique à l’usage des artistes, suivis de réflexions et conseils à un élève sur la peinture et particulièrement sur le genre du paysage (Paris: l’auteur, Desenne, Duprat, an VIII [1799]), https://gallica.bnf.fr/. See also Carole Rose Wenzel, “The Transformation of French Landscape Painting from Valenciennes to Corot, 1787 to 1827” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1979).

[11] “Un des plus grands défauts des Paysagistes, c’est que lorsqu’ils ont une fois adopté une touche de feuilles qui leur paroît bonne, ils l’emploient à représenter toutes sortes d’arbres. . . . Chaque espèce d’arbres a une manière particulière de jeter ses branches, & ses paquets de feuilles ont une forme qui lui est particulière.” Jombert, Méthode pour apprendre le dessein, 115.

[12] Jombert, Méthode pour apprendre le dessein, 116–18.

[13] Camille Pissarro to his son Lucien, 1883, in Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, ed. Janine Bailly-Herzberg, vol. 1, 1865–1885 (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1980), 259–62.

[14] “Notre Élève a pendant quelques mois dessiné sous nos yeux; il a copié plusieurs tableaux des meilleurs maîtres, mais il n’a pas vu la Nature.” Valenciennes, Élémens de perspective pratique, 404.

[15] See Mai-mai Sze, The Tao of Painting: A Study of the Ritual Disposition of Chinese Painting, with a Translation of the Chieh Tzu Yüan Hua Chuan or Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, 1679–1701 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1956; Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1967). I thank Petra ten-Doesschate Chu for this reference.

[16] On Cozens’s landscape productions, see Kim Sloan, Alexander and John Robert Cozens, The Poetry of Landscape, exh. cat. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press for the Art Gallery of Ontario, 1986).

[17] They produced four portfolios, 1774–77. The first was by Jean Philippe Sarazin and Jean-François Janinet, Premier Cayer de paysage dessiné d’après nature par Sarazin et gravé par F. Janinet en 1774 (Paris: Le Pere et Avaulez, [1774]).

[18] Alexander Cozens, A New Method of Assisting the Invention in Drawing Original Compositions of Landscape (London: J. Dixwell, ca. 1785), 43 prints.

[19] N. Al. Michel [Alphonse Nicolas-Michel] Mandevare, Principes raisonnés du paysage à l’usage des écoles des départements de l’Empire français (Paris: Boudeville, 1804 [5 Frimaire, an 13]), https://gallica.bnf.fr/. There has been very little written on Mandevare; see Marianne Joannides, “Mandevare’s Drawings: Le Rouge et le Noir,” Phillips Review (Autumn 1982): 6–7. I thank Asher Miller for this reference.

[20] Valenciennes, Élémens de perspective pratique, 226.

[21] There has been little scholarship on the Prix de Rome for landscape. Philippe Grunchec has published a number of volumes that give some information but largely focus on the history-painting competitions. See Philippe Grunchec, Les Concours des Prix de Rome de 1797 à 1863, exh. cat. (Paris: École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 1983), 1:31–32, 205–31; Grunchec, The Grand Prix de Rome, Paintings from the École des Beaux-Arts, 1797–1863, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: International Exhibitions Foundation, 1984–85), 27; and Grunchec, Les Concours d’esquisses peintes, 1816–1863, exh. cat. (Paris: École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 1986), 1:22–23.

[22] On Michallon’s prize, see Grunchec, Concours des Prix de Rome, 1:206. On the suppression of the Prix de Rome for landscape, see Albert Boime, “The Teaching Reforms of 1863 and the Origins of Modernism in France,” The Art Quarterly, n.s., 1 (Autumn 1977): 1–39.

[23] See Grunchec, Grand Prix de Rome, 27.

[24] On Giroux, see Grunchec, Concours des Prix de Rome, 1:210–11. The Calydonian boar hunt, the source for this painting, is narrated in Book 8 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

[25] On Buttera, see Grunchec, Concours des Prix de Rome, 1:216–17.

[26] C. Bourgeois, Études d’après nature dédiées aux jeunes paysagistes (Paris: Delpech, 1822); Augustin Enfantin, Croquis progressifs de paysage d’après nature (Paris: Gihaut, 1824); and J. Vasserot, Études d’arbres (Paris: C. Constans, 1824). Daniel Harlé gives an extensive listing of nineteenth-century French drawing manuals, both figure and landscape, in “Les Cours de dessin gravés et lithographiés du XIXe siècle conservés au Cabinet des Estampes de la Bibliothèque nationale. Essai critique et catalogue,” 4 vols. (PhD diss., École du Louvre, 1975). Jean Adhémar lists lithographed landscape drawing manuals published between 1825 and 1854 in La France romantique: Les lithographies de paysage au XIXe siècle (Paris: Somogy, 1997), 111–31.

[27] “Pour bien connoître la forme d’un arbre de ses branches, il faut le dessiner pendant l’hiver, lorsqu’il est dépouillé de ses feuilles; on en saisit alors la structure, et l’on se rend compte de toute sa charpente.” Valenciennes, Élémens de perspective pratique, 226.

[28] Grunchec, Les Concours des Prix de Rome, 1:31–32.

[29] For a related discussion, see Susan S. Waller, The Invention of the Model: Artists and Models in Paris, 1830–1870 (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2006).

[30] William Henry Pyne, Microcosm, or a Picturesque Delineation of the Arts, Agriculture, Manufactures, &c. of Great Britain, in a Series of above Six Hundred Groups of Small Figures for the Embellishment of Landscape, 2 vols. (London: S. Gosnell for William Miller, 1806). It was issued in parts beginning in 1802, with the first collected volume published in 1803, the second in 1806; these were followed by numerous reprintings, often under slightly different titles and with additions.

[31] François Fortuné Antoine Férogio, Études progressives de figures pittoresques à l’usage des paysagistes (Paris: Gihaut Frères, 1839).

[32] “24 études d’animaux, destinées à servir de modèles aux élèves et de motifs aux paysagistes pour animer leurs tableaux,” Le Charivari, March 26, 1835, 4. Victor Adam, Étrennes aux paysagistes (Paris: Aubert; London: Charles Tilt, 1832; reprinted 1835). It was again reprinted in 1853 on better paper as Étrennes aux paysagistes, Études d’animaux destinés à meubler les tableaux et dessins de paysages (Paris: A. Bès et F. Dubreuil, 1853).

[33] For a discussion of albums, see Patricia Mainardi, Another World: Nineteenth-Century Illustrated Print Culture (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017), 48–55; and Ségolène Le Men, “Quelques définitions romantiques de l’album,” Art et métiers du livre, no. 143 (February 1987), 40–47.

[34] “Les temps sont durs (vous l’avez sans doute entendu dire) et le public qui singe toujours son roi devient tous les jours plus avare, il faut, pour l’amener à débourser un sou, lui donner un écu. Or, j’ai fait éditer à mon beau-frère [Aubert] de petites macédoines qui, sur une seule feuille, contiennent vingt et vingt-quatre petites images. C’est tout-à-fait de la marchandise, j’en conviens, mais c’est la seule chose qui se vende et Aubert appelle cela un chef-d’œuvre.” The letter is reprinted in Maximilien Gauthier, Achille et Eugène Devéria (Paris: H. Floury, 1925), 79.

[35] “Collection de cent planches environ de jolis petits dessins dans tous les genres, dans toutes les formes, et toutes les dimensions. Ces dessins, réunis en nombre quelquefois infini sur une seule feuille, qui ne se vend que 1 fr., sont destinés à tous les usages du cartonnage et de la papeterie. Ils se découpent, se décalquent, se colorient, se collent sur des boîtes, sur des écrans, servent de petits sinets [signets], de petits modèles pour apprendre à croquer; coloriés avec goût, ils s’emploient à former des albums qui imitent parfaitement l’aquarelle. Les feuilles se vendent séparément. Là se retrouvent tous les noms d’artistes connus et aimés du public; chacun a fait au moins sa feuille, quelques-uns en ont fait plusieurs.” Petites macédoines d’Aubert, in the Prospectus for Le Charivari [1832], n.p.

[36] “250 Petites macédoines, dites Macédoines d’Aubert,” advertisement in La Caricature, no. 232, April 16, 1835.

[37] On découpage as an entertainment for the leisured classes, see David Pullins, “The State of the Fashion Plate, c. 1727: Historicizing Fashion between ‘Dressed Prints’ and Dezallier’s Recueils,” in Prints in Translation, 1450–1750: Image, Materiality, Space, ed. Suzanne Karr Schmidt and Edward H. Wouk (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), 136–57.

[38] Nicolas-Toussaint Charlet, Suite de dessins à la plume à l’usage des élèves des Écoles spéciales des ponts et chaussées de Metz, d’état-major et autres, 1839. Lithographs. The portfolio in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France Réserve is stamped “École Polytechnique” and carries a note saying that the plates were lithographed by François Villain for Charlet’s drawing course to serve as models for his students but were never circulated commercially. The portfolio was subsequently reissued for the broader market as Suite de dessins à la plume à l’usage des élèves spéciales des ponts et chaussées de Metz, l’état-major, polytechnique, militaire et autres (Paris: Gihaut Frères, 1842).

[39] Achille-Etna Michallon, Cahier de 4 paysages dessinés d’après nature (Paris: lith. comte de Lasteyrie, 1817). On Corot’s training, see Vincent Pomarède, “The Making of an Artist,” in Gary Tinterow, Michael Pantazzi, and Vincent Pomarède, Corot, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996), 5–57.

[40] Jean-Victor Bertin. Recueil d’études d’arbres (Paris: lith. Bertin and Engelmann, 1821–24), 45 plates. On Bertin, see Suzanne Gutwirth, “Jean-Victor Bertin, un paysagiste néoclassique (1767–1842),” Gazette des beaux-arts, no. 83 (May–June 1974): 337–58.

[41] For an excellent discussion of the subject of British landscape drawing manuals, see Christiana Payne, Silent Witnesses: Trees in British Art, 1760–1870 (Bristol, UK: Sansom, 2017), 63–87; on Turner, see 144–46. On British drawing instruction in general, see Ann Bermingham, Learning to Draw: Studies in the Cultural History of a Polite and Useful Art (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000); and Kim Sloan, “A Noble Art”: Amateur Artists and Drawing Masters, c. 1600–1800 (London: British Museum Press, 2000).

[42] Grunchec discusses the painting in Les Concours des Prix de Rome, 1:8–9. On Rémond, see also Suzanne Gutwirth, “Jean-Charles-Joseph Rémond (1795–1875), premier grand prix de Rome du paysage historique,” Bulletin de la Société d’histoire de l’art français (1981): 189–203.

[43] Rémond’s published portfolios are Principes de paysage, dessinés sur pierre (Paris: Delpech, 1826) and Cours complet de paysages, dessinés sur pierre (Paris: Delpech, 1829). On Rousseau’s copies of Rémond’s drawings, see Philippe Burty, Maîtres et petites-maîtres (Paris: Charpentier, 1877), 124.

[44] “mais il faut d’abord dessiner d’après les modèles graphiques, pour savoir comment on doit s’y prendre.” Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, Histoire d’un dessinateur. Comment on apprend à dessiner (Paris: J. Hetzel, 1879), 70–71. It was translated by Virginia Champlin as Learning to Draw; or, the Story of a Young Designer (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1891).

[45] Ernest Gombrich, Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (London: Phaidon; New York: Pantheon, 1960), 84.

[46] Although Strick concluded that landscape drawing manuals died out at mid-century, the end date of Jean Adhémar’s bibliography (see notes 4 and 26 above), new manuals continued to be produced. Le dessin de paysage étudié d’après nature by H. Guiot [Guillot] and Jules-Jean Pillet, for example, was first published in 1889 and reprinted in 1896, 1899, 1921, and 1925. Earlier works were often reprinted as well; for example, Jean-Pierre Thénot’s Les Règles du paysage mises à la portée de toutes les intelligences (1841) was reprinted in 1884.

[47] On Monet’s poplars, see Paul Hayes Tucker, Monet in the ’90s: The Series Paintings, exh. cat. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1989), 115–51. Although the poplar did have a political significance during the French Revolution, Tucker concludes that Monet was much more interested in its decorative elements.