The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

As a sculptural companion piece and thematic revision of The American Slave, The Octoroon by John Bell (1811–95) debuted on exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1868 (figs. 1, 2). It reappeared popularly thereafter, reproduced in ceramics by Minton and Company, bronzes by the Coalbrookdale Company, and stereographic images. Bell’s original statue stands over five feet high, every inch of which contradicts itself. The sculptor’s dialectical iconography codes his female subject as ethereal and abject, ancient and modern, white and black, nude and naked. He created The Octoroon in the medium of marble, but he marketed her in the genre of mid-nineteenth-century melodramas of race, caste, and sex.

Deprived of any garment whatsoever, the body of The Octoroon, like her predicament, is more complicated than that of The American Slave. With European features, classical proportions, and elegant pose, she appears to be conventionally nude as well as white. While she opposes her limbs and stands contrapposto—right arm raised, left leg placed forward across the right one, which bears what corporeal weight there is to bear—the statue’s essentially cylindrical composition contains her ethereal gesture of modesty, assisted by the careful arrangement of her thigh-length hair. The drama of her contingent circumstances, however, strips her naked. Although evoking the form of Sandro Botticelli’s Venus, Simonetta Vespucci, she plays the role of the “Hottentot Venus,” Saartjie Baartman—hyper-sexualized, hyper-racialized, and spectacularly exhibited. Like The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers, the phenotypical whiteness of her features signifies in opposition to the chains that bind her wrists, a contradiction heightened by the whiteness of the marble from which is she carved. Taken together, however, these attributes mark her indelibly as a specialized kind of American slave, a white-appearing woman tragically fallen from a life of middle-class security and made eligible for sale into life-long concubinage by virtue of the discovery of one invisible characteristic. Both the statue and the subject of the statue exist ontologically as marketable objects. Bell depicts her as if she has been disrobed for inspection at an auction, lowering her head and turning it aside in mortification at the very moment she is gaveled down as sexual chattel on the block of antebellum America’s “peculiar institution,” which marked all black bodies as enslaved, even those whose blackness was consisted of but one-eighth African blood, hence, an octoroon.

When I first wrote about this statue twenty years ago, I misattributed John Bell’s nationality to the United States.[1] I regret the error, and I am glad to have the chance to correct myself here. At the same time, Bell’s suave mastery of the lunatic preoccupations of American social relations, which make race a libidinous category as well as a lethal one, shows him to have been well informed. He seems likely to have done his research for The Octoroon in perusal of one or two of the well-elaborated descriptive sources available to him as he worked on the statue as early as 1863: Dion Boucicault’s play The Octoroon; or Life in Louisiana (1859), which was performed in London in 1861 (fig. 3); or Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s novel The Octoroon; or, the Lily of Louisiana (serialized 1861–62). Bell’s statue ought to be understood as belonging to the international sensation created by these dramatic and narrative materials as well as by nonfiction accounts of very real sexual bondage.

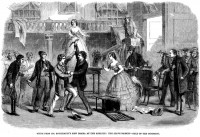

Boucicault dramatizes the “life” of Louisiana through the vicissitudes of Zoe, the title character, who ends up on the auction block at the mercy of the highest bidder. Well-educated and well-spoken, Zoe had been mistress of Terrebone Plantation until the deed of gift that freed her from slavery, written by her guilt-ridden father in remembrance of her quadroon mother, proves faulty, allowing the villain of the piece to foreclose on the property, which perforce includes the octoroon. For this, she reproaches herself. “Of all the blood that feeds my heart,” she confesses, “one drop in eight is black.” Despite the predominant color of the remainder (bright red), “this one black drop gives me despair, for I am an unclean thing—forbidden by the laws—I’m an Octoroon!”[2] The most widely sensationalized scene from the production of Boucicault’s play shows Zoe standing tabletop while the frenzied bidders compete for ownership. Braddon narrated the closely parallel fate of Cora, the titular “lily.” She wrote the novel before Boucicault’s play opened in London. It appears likely that both works may have had a common source in Mayne Reid’s The Quadroon; or, a Lover’s Adventures in Louisiana (1856), though the “tragic mulatta” plot had already become a staple of popular fiction and abolitionist propaganda. The climactic moment of each work takes place at a New Orleans slave auction, as I believe the pregnant moment represented in John Bell’s statue does.

Boucicault’s and Braddon’s flesh-market scenes, though highly melodramatic, were not wholly fictionalized. In The Slave Auction (1859), John Theophilus Kramer sent back an eye-witness account from New Orleans to his antislavery sponsors in Boston: “There stands a girl upon the platform to be sold to the highest bidder; perhaps a cruel, low and dissolute fellow, who, for a day or two since, won a few thousand dollars by playing his tricks at the faro table. She is nearly white; she is not yellow, as they call her. She has a fair waist, her hair is black and silky, and falling down in ringlets upon her full shoulders. Her eyes are large, soft, and languishing.”[3] The plea for empathy from the dominant culture that Kramer makes by highlighting the whiteness of the mixed-race octoroon serves as a convenient excuse to raise the erotic stakes by elaborating her physical attractions. Kramer and others noted that conventions at The Rotunda, the main New Orleans auction venue, where real estate and artworks were sold alongside human beings, called for slaves to be stripped to permit potential bidders to examine their wares (fig. 4). While not calling for full nudity in their fictions and staging, the authors managed to insinuate the titillating shock of bared flesh—not in an ancient or exotic setting like The Greek Slave, but in a contemporary transatlantic one—that John Bell literalizes in his sculpture. I do not know if Bell read Braddon’s novel, but her description of her title character’s appearance on the block—“never when surrounded by luxury, when surfeited by adulation and respect, had Cora Leslie looked more lovely than today”—was written as if with a programmatic intention for a sculptural commission: “Her face was whiter than marble, her large dark eyes were shrouded beneath drooping lids, fringed with long and silken lashes; her rich wealth of raven hair had been loosened by the rude hands of an overseer, and fell in heavy masses far below her waist; her slender yet rounded figure was set off by the soft folds of her simple cambric dress, which displayed her shoulders and arms in all their statuesque beauty.”[4]

Well-educated and by all visible cues socially presentable in Grosvenor Square, Cora came from the caste of light-skinned Louisiana creoles who could be slaves or slave owners depending on arbitrary circumstances. I believe that it was precisely such a catastrophic twist of fate as in Cora’s case—the belle of the ball in London, the “fancy girl” sex puppet on sale in New Orleans—that Bell set in stone. The iconography of The Octoroon thus leaves the beholder to ponder the sexual enslavement of women generally, race notwithstanding, in a culture of rampantly merchandized objectification. The question lingers even as the sculptures of John Bell, Hiram Powers, and other Victorians reassert their importance in the history of art and history writ large. The casting note that prefaces Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s An Octoroon (2014), a mordant rewriting of Boucicault for a putatively “post-race” generation, foregrounds the potential instability of “race” in the crucible of miscegenation: “ZOE—played by an octoroon actress, a white actress, a quadroon actress, a multi-racial actress, or an actress of color who can pass as an octoroon.”[5] In the unresolved tensions of such a bodily identity, her subject-position turned contrapposto, the contradictions of John Bell’s statue, like the repressed, continue to return.

[1] Joseph Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), 220.

[2] Dion Boucicault, The Octoroon; or Life in Louisiana (1859; repr. Miami: Mnemosyne, 1969), 17.

[3] John Theophilus Kramer, The Slave Auction (Boston: Robert F. Walcott, 1859), 26.

[4] M. E. Braddon, The Octoroon; or, the Lily of Louisiana (1861–62; repr. New York: George Munro’s Sons, 1895), 125.

[5] Branden Jacob-Jenkins, An Octoroon (New York: Dramatists Play Service, 2014), 4.