The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

By many accounts, one of the star sculptures at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations of 1851 was The Greek Slave (1844, first version, Raby Castle, Staindrop; fig. 1) by the American sculptor Hiram Powers (1805–73). Displayed on a rotating pedestal and shrouded by red velvet drapery, Powers’s statue of a young Christian woman taken into Ottoman captivity during the Greek War of Independence occupied a prominent place in the American section. In addition to eliciting a great deal of attention at the exhibition, the sculpture was reproduced in seemingly limitless media, forms, and contexts. Whether it was pictured in daguerreotypes and stereographs, reduced in Parian ware, satirized in cartoons, or appropriated in advertisements, The Greek Slave engendered entrepreneurial acts of image making, each of which transformed and reimagined the model of the original marble statue in novel ways.[1]

The British sculptor and industrial designer John Bell (1811–95) was one of many artists who responded to and participated in the explosion of visual and material culture surrounding The Greek Slave in mid-nineteenth-century England. Shortly after the Great Exhibition, Bell began to make plans to produce a bronze sculpture modeled in part after Powers’s Greek Slave. He collaborated with the leading British metal manufacturing firm Elkington and Company to do so, conceiving of a work that would be, as he noted in a letter, “on the same scale and in the same style as the Greek Slave.”[2] To this he added a postscript about the stakes of the subject at hand, writing, “There is (I think), no time to be lost if the statue is to have the opportunity of being well seen & known this year.”[3]

The resultant work, first displayed by Bell as a plaster at the 1853 exhibition of the Royal Academy under the title A Daughter of Eve—A Scene on the Shore of the Atlantic, depicted a young woman of African descent enslaved and enchained (fig. 2).[4] Its various titles since, including The Negress Slave, The Slave Girl, and The American Slave, suggest that there was—and continues to be—much at stake in Bell’s representation of the enslaved black body and its relationship to the geographic and historical context of American slavery.[5] As the art historian Michael Hatt has persuasively argued, the sculpture constituted a timely abolitionist appeal in mounting debates about the system of slavery as it persisted in the Americas.[6] Produced as a bronze electrotype by Elkington and Company soon after Bell’s completion of the plaster, it gained widespread visibility in the British Isles as the firm reproduced, displayed, and marketed life-size and reduced versions of the statue at world’s fairs and industrial exhibitions in the decades to follow.

This essay considers the dynamics of race and power at play in the statue’s production and patronage, taking as its focus a full-scale version produced by Elkington in 1862 and subsequently acquired by the British armaments manufacturer William Armstrong, 1st Baron Armstrong (1810–1900) for his country home at Cragside in Northumberland. With The American Slave, Bell created a work of art that called into question the logic of slavery’s commodifying structures as they related to the human body. Yet the object’s simultaneous status as a sculptural representation of an anonymous and enslaved black female subject and as an object of industrial manufacture and consumption complicated its relationship to antislavery ideology. As a study of Elkington’s production and Armstrong’s patronage will demonstrate, the sale and consumption of a life-size, sculptural representation of an enslaved body paradoxically threatened to reinscribe the proprietary violence of the system of slavery that Bell and many others sought to challenge.

“A scene on the shore of the Atlantic”

The American Slave was unusual for its time. The bronze sculpture shows a young black woman with wrists bound together by a chain. The figure wears a wrap at the waist but is otherwise nude, and casts a gaze downward in an expression that suggests melancholy and fatigue. As several scholars have noted, Bell created his sculpture at a moment when many artists eschewed such subjects on the racist grounds that blackness stood outside of Western, Eurocentric notions of the ideal human form.[7] If the theme of the captive figure was a popular one for sculptors on both sides of the Atlantic, it remained largely confined to the white subject and the medium of white marble, as works such as Powers’s Greek Slave, Erastus Dow Palmer’s White Captive (1858–59, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), and Raffaele Monti’s Circassian Slave (ca. 1851, The Wallace Collection, London) attest. In creating The American Slave, Bell departed from prevailing sculptural conventions in terms of his chosen material and subject matter. As I will suggest here, the representational choices he made in the process resulted in a work fraught with contradiction, legible as both a lifelike body and an object of manufacture.

If The Greek Slave garnered praise as a subject who bore the burden of her captivity with calm and serenity, The American Slave would appear to be anything but serene. Bell’s figure wears a weary expression, accentuated by deep-set eyelids and a furrowed brow. The statue’s posture is tense, and the muscles of the arms and shoulders strain visibly from the heavy silver chain. This stance differs distinctly from the one Bell deployed two years earlier in his statue Andromeda, where the mythological figure’s chained hands were placed behind the back rather than in front of the body (fig. 3). By contrast, the pose he adopted with The American Slave suggests that the figure stands so as to prop up and support the weight of the chain, whose links hang to the knees. This posture is further accentuated by the figure’s hunched shoulders and a twisting pose that seems to communicate a set of resistant gestures designed to shield the nude body from an invasive gaze.

With these choices, Bell created a sculpture that could support abolitionist readings. The figure appears as an affective subject responding to and resisting the conditions of enslavement. As one critic noted upon seeing the statue at the Royal Academy in 1853, “She is erect but weeping; on her wrists are chains. The allusion is at once intelligible.”[8] The viewer is brought to acknowledge the ways in which this subject, bound in chains and standing on a rocky base with a strand of seaweed and a seashell, is implicated in what the cultural historian Katherine McKittrick has called the “human geographies of slavery” and its commercial networks.[9] Bell’s original Royal Academy title, A Daughter of Eve—A Scene on the Shore of the Atlantic, supports this point by indicating a discrete geographic and narrative context for the sculpture, as if it were a tableau. As Michael Hatt has pointed out, the biblical phrase “a daughter of Eve” was often evoked by nineteenth-century abolitionists to suggest that all individuals, enslaved or not, shared Edenic origins.[10] Perhaps more so than any other sculpture of its day, The American Slave could compel nineteenth-century viewers to acknowledge the slave trade as a geographic network implicated in the displacement and commodification of millions of people.

Yet The American Slave was at once a body, a work of art, and an object of industrial manufacture. The figure stands five feet high, and its life-size scale and three-dimensionality lend the subject a bodily presence and engender an anatomizing gaze. To fully take in the sculpture’s form at close range, one must either physically circumnavigate it or look it up and down. As noted above, Bell paid close attention to the subject’s appearance and body language in a way that exceeded the aesthetic and narrative conventions of ideal sculpture to suggest a sensing subject burdened by her enslavement. But aspects of the sculpture’s surface—a highly polished and uniform sheen, the lack of a belly button, and the incorporation of gold and silver ornamentation—disclose its status not as a body but as a fabricated thing produced by the modern alchemy of Elkington’s electrotype baths (fig. 4).[11] What follows attends to these implicit tensions by considering the sculpture’s dual status as both representation of a commodified body and commercial object.

It is critical here to acknowledge the uneven power dynamics of race and gender enacted by sculpture’s production: a white male sculptor creating—physically modeling—a representation of a female slave, ostensibly in the name of abolitionist politics. As the literary critic Saidiya Hartman argues, representing the vulnerability and pain of enslavement for the sake of empathetic “identification” on the behalf of (largely white) audiences can result in a dangerous feedback loop. Hartman asks, “Does this not reinforce the ‘thingly’ quality of the captive by reducing the body to evidence in the very effort to establish the humanity of the enslaved?”[12] The fact that The American Slave was also conceived by Bell and Elkington as a commodity in and of itself—an object of industrial manufacture, of marketing and desire—further complicates and compounds this matter. To follow a line of inquiry proposed by the art historians Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson, what happens when the logic of commodification takes the body of the enslaved as its object?[13] More specifically, what was at stake in the marketing and consumption of a sculpture whose very allusion to slavery happened by means of the representation of the body of the enslaved? In addressing these questions, it is productive to explore in greater depth the work’s industrial modes of manufacture and commercial contexts of display.

Metalwork

Though first modeled in plaster in Bell’s London studio, The American Slave had its origins as a bronze sculpture in Birmingham, the site of Elkington and Company. Situated in a region rich in ore deposits, Birmingham and the West Midlands have long been synonymous with industry and metal manufacture. Mining constituted one of the region’s main economic activities as early as the Middle Ages, and production later accelerated with the technological developments of the Industrial Revolution and the creation of the city’s network of canals, which facilitated the export of goods around the globe.[14] In the words of Samuel Timmins, who authored a sweeping and influential survey of the area’s industry in 1865, “Within a radius of thirty miles of Birmingham nearly the whole of the hardware wants of the world are practically supplied.”[15]

A significant portion of Birmingham’s exports included metal wares for the slave trade.[16] From the opening of the Atlantic trade to Britain in 1698, Birmingham manufacturers shipped guns, chains, shackles, jewelry, and currency to the western coasts of Africa, where they were exchanged for slaves. British exports to Africa and the Americas persisted into the nineteenth century despite parliamentary acts that abolished the slave trade and slavery in 1807 and 1833 respectively.[17] The legislation, while significant, did not bring British complicity in Atlantic and American slave systems to a full stop. As one commissioner to Parliament inquired in 1838, “With what but British goods is the African market, the freight which is to be bartered for the slave, supplied? With what but slave labour are the works, originating in British capital and enterprise, carried on in this country?”[18] As these words reveal, despite ideological challenges to and legislative injunctions against the trade, England—and the West Midlands specifically—remained an active participant in the material sustenance of slavery long after its abolition within the British Empire.

A survey of Elkington’s records and trade catalogues yields no evidence that the company produced metal goods for the slave trade.[19] Rather, their production may be grouped into two general categories: luxury wares such as candlesticks, vases, and tea services; and electrotype objects that the company marketed as “art manufactures.” This latter group included sculpture by contemporary artists such as Bell, as well as cast reproductions of older objects, particularly sixteenth- and seventeenth-century European sculpture and decorative arts.[20] Their production, which began in the 1830s and rapidly grew in following decades, demands consideration within a broader history and landscape of Birmingham metal manufacturing.

If Elkington did not make wares for the slave trade, why might it be productive to examine their manufacture of luxury objects in this wider industrial context? The critical interventions of the contemporary artist Fred Wilson convey the methodological urgency of taking into account the production of such goods when examining the diffuse scope of nineteenth-century slave economies.[21] In Mining the Museum, his landmark exhibition at the Maryland Historical Society in 1993, Wilson paired a set of finely wrought silver wares with a set of iron manacles in a vitrine (fig. 5).[22] This display—“Metalwork, 1793–1880”—compelled audiences to confront the coexisting material cultures of white luxury and black oppression in nineteenth-century slaveholding America. In so doing, Wilson’s work visually and materially insists on what the art historian Kay Dian Kriz identifies as a circum-Atlantic world of “rudeness and refinement,” wherein the production of metropolitan luxury cannot and must not be considered without heed to the subject(s) of empire and slavery.[23] The work of artists such as Wilson and scholars such as Kriz offers a useful framework for understanding Elkington’s place within the metal trade in the nineteenth-century Atlantic world.

Though destined for different markets, luxury goods produced by Elkington in bronze, gold, and silver nevertheless shared a similar materiality and technology of manufacture with the jewelry, manillas, and ornamental wares made in Birmingham for shipment to western Africa, the Caribbean, and the southern United States. The writings of Connecticut-born Elihu Burritt, who served as the American consul in Birmingham in the 1860s and did much to popularize Elkington’s wares in the United States, lend further insight into period associations attached to the city’s metal industry. As he remarked in his report on the region’s industrial history,

Birmingham . . . has “worked to order” without asking questions for conscience sake in regard to the uses made of its articles of iron and brass. It has made all kinds of cheap and showy jewels for the noses and ears of African beaux and belles, and stouter bracelets of iron for the hands and feet of slaves driven in coffles to the sea-board. In the same shops and on the same benches, gilt and silver buckles were made by the million for the shoes of the nobility and gentry.[24]

The ironies of manufacture Burritt described are strikingly similar to the ironies of material juxtaposition that Wilson’s installations would evoke nearly a century and a half later. But if Wilson’s work of the early 1990s deployed the aesthetics of contrast to present a shocking juxtaposition between different metal markets of the nineteenth century, Burritt’s writing and Bell’s sculpture exposed the extent to which those markets were always already entangled with one another. Especially noteworthy in Burritt’s report is his emphasis on the fact that the different objects produced by Birmingham’s workshops did not exist in isolation from each other in the minds of contemporaries. Rather, they could be perceived as two sides of the same coin.

The practices and objects of manufacture described by Burritt collide in the form of The American Slave. The gold hoop earrings and silver-plated chain worn by the figure are markedly similar in material and function to the hardware produced by other Birmingham foundries and jewelers for the Atlantic slave trade and, after 1807, the American domestic slave trade. Both items have been cast separately and attached to the statue. The hoop earrings, similar to those worn by enslaved women, are affixed to the ears through small holes wrought into surface of the bronze, and the chains are fastened together by an interlocking pin system.[25] The objects incorporated onto and into the surface of the statue substitute “signs of the real for the real,” to borrow Jean Baudrillard’s language, standing out from the figure’s bronze form as unsettling simulacra of the violent methods employed to commodify the enslaved, both with instruments of oppression and with objects of value.[26]

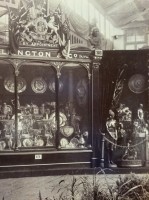

What was at stake in the statue’s simulation of slavery’s material structures of commodification by way of the metal surface and object? First, The American Slave inserted the subject of slavery and the enslaved subject into spaces where both were otherwise not present. The sculpture gained its primary forum of public visibility across the nineteenth century by way of Elkington and Company, appearing on view in the firm’s lavish Birmingham showroom, the site of a former ironmonger’s shop. It also stood in industrial exhibitions, including the Irish Exhibition of 1853, the London International Exhibition of 1862, and the Birmingham Industrial Exhibition of 1886 (fig. 6). While the contents and contexts of each of these spaces differed undeniably, they shared the key attribute of showcasing the products and progress of modern British industry. Fairs celebrated the mechanized and skilled labor that animated the nation’s industrial production, and in official literature this genre of work was frequently held up in rhetorical opposition to the enslaved labor that took place on the other side of the Atlantic.[27] By way of its subject matter and its materiality, The American Slave had the potential to disrupt the rhetoric of national progress by making visible and exposing the complicity between local manufacturing and a wider circulatory network of goods, people, goods traded for people, and people traded for goods—a transactional and transnational zone of capital accumulation that the economist Giovanni Arrighi has termed a “space-of-flows.”[28]

This visibility may have had a second, more precarious implication. At international exhibitions, the sculpture was often staged and marketed as a commercial object alongside other luxury wares by Elkington. Elkington’s visitor books from these events are filled with orders and commissions from buyers around the world, revealing that such displays were important venues for the company’s sales at home and abroad.[29] Yet in appraising and inspecting a life-size statue whose surfaces simulated the violent conditions of enslavement, prospective customers may have also (however unknowingly) enacted the speculative modes of looking associated with the buying and selling of people at slave markets and auctions. Following Joseph Roach’s important thesis that the Atlantic world was a “vast behavioral vortex” in which the “semiosis of conspicuous consumption [recapitulated] the triangular trade in material goods and human flesh,” Bell’s work cannot be understood on the terms of antislavery ideology alone.[30] If the sculpture made visible the enslaved subject at exhibitions, it also risked making present in these spaces the proprietary power dynamics that fueled the sale and purchase of human bodies elsewhere, as Roach argues in his article in this special issue. We need only refer to John Boyne’s satirical watercolor depicting a group of white men inspecting the body of a black male model in an artist’s studio to see how practices of connoisseurship could be understood to be conditioned by racialized and racist gazes (fig. 7). As scholars have pointed out, Boyne’s watercolor, which was produced at the turn of the nineteenth century, is suggestive of a shared modality of visual assessment at work both at slave auctions and in the art world.[31] I want to suggest that the site of the world’s fair—a spectacular space that Walter Benjamin would later famously describe as one that glorified the exchange value of the commodity—further heightened this practice of racialized looking.[32]

This is not to impute one specific mode of viewer engagement to Bell’s sculpture, but rather to underscore the ways in which the work’s status as a representation of a commodified body may have complicated—or even vexed—its potential for ideological import. When the South Kensington Museum’s George Wallis saw The American Slave in Elkington’s installation at the 1862 International Exhibition, he described the statue as “an appeal against the blasphemous hypocrisy which attempts to justify human bondage” but concluded that it was “happily embodied in a singularly suitable material.”[33] Wallis’s comments regarding both the sculpture’s subject matter and its materiality highlight the instability and obliqueness of an object that traversed overlapping landscapes of art, industry, and commerce. If The American Slave could operate as an ideological challenge to the institution of American slavery by exposing the system’s morally corrupt processes of commodification, so too could the sculpture relocate and reproduce these very processes within its commercial contexts of display across the Atlantic.

Armstrong’s Acquisition

The eventual acquisition of one version of The American Slave by the English industrialist William Armstrong sheds further light on the problem of purchasing and owning a sculptural representation of an enslaved body. Trained as a lawyer but an engineer by trade, Lord Armstrong owned a successful manufacturing company based at Newcastle, which specialized in the production of hydraulic machines, ships, and guns.[34] In the 1850s, he developed an eponymous breech-loading rifle, which, as Hatt has noted, would be later used by both Union and Confederate armies fighting in the American Civil War.[35] With wealth accumulated from this invention and the armaments industry more generally, Armstrong amassed a formidable collection of modern British art that included works by Joseph Mallord William Turner, Frederic Leighton, and John Everett Millais, among others.[36] Sometime in the late 1860s or early 1870s, he acquired a full-size version of The American Slave. Like the other works of art in his collection, the sculpture was destined for his home at Cragside, a sprawling estate in a remote pocket of Northumberland, built between 1864 and 1884 (fig. 8). His acquisition and display of the sculpture offer further testimony to the deeply unstable nature of Bell’s representation and the ways it could be consumed simultaneously as an expression of abolitionist sentiment, a display of wealth, and an object of desire.

The circumstances surrounding Lord Armstrong’s acquisition of The American Slave remain murky. The sculpture had been purchased in 1862 by Richard Seymour-Conway, 4th Marquess of Hertford and benefactor of the Wallace Collection, and passed into Armstrong’s possession several years thereafter.[37] Elkington’s signed visitor books reveal that Armstrong went to the company’s Birmingham showroom in 1865, one year after construction began at Cragside.[38] Whether Armstrong visited with specific knowledge of Bell’s work or with a more general interest in purchasing wares and decorations for his new home, he would have likely seen the statue on display in the showroom that a contemporary declared to “look more like a city hall or an art gallery than a factory of the useful kind.”[39] But the lacunae of the statue’s history of transaction between Seymour-Conway and Armstrong perhaps speak to the ways in which the medium and subject of this object—an electrotype statue of a slave produced by a manufacturing company—may have eluded easy categorization by collectors more inclined to own landscape paintings, genre scenes, and marble sculptures.

Representing Slavery at Cragside

If Armstrong’s exact motivations behind his acquisition of The American Slave remain unclear, it is known that he harbored views against slavery generally, and other objects in his collection attest to this.[40] He kept, for instance, in his library a miniature marble column whose plinth was inscribed with the words “Patria Cara Carior Libertas” (“Country is dear, but freedom is dearer.”) and inlaid with Josiah Wedgwood’s famed 1787 antislavery medallion with a jasperware bas-relief of a kneeling, enchained black man encircled with the words “Am I not a man and a brother?” (fig. 9). According to Mary Guyatt, composite and customized objects incorporating Wedgwood’s medallion were popular ways of expressing support for abolitionist politics in eighteenth-century Britain.[41] The presence of such an object alongside The American Slave is suggestive of Armstrong’s engagement with a longer visual and commercial tradition of British antislavery ideology, one whose moral appeals to justice were frequently inflected by paternalist and racializing attitudes. Though over six decades separated the initial production of Wedgwood’s medallion and that of Bell’s sculpture, both were commercially manufactured objects that mobilized sculptural images of enslaved black bodies in the interest of abolitionism.

Significantly, the institution of slavery had been outlawed in both the British Atlantic and in North America by the time Armstrong acquired The American Slave. His embrace of abolitionist imagery was belated, and may have dovetailed with his own professional interests. The art historian Dianne Sachko Macleod has argued that, for Victorian industrialists such as Armstrong, collecting functioned not only as a mode of self-fashioning but also as a vital means of asserting one’s professional identity and social values.[42] Cragside was above all a modern house built on modern money and modern ingenuity, incorporating state-of-the-art hydraulic and electrical infrastructure of Armstrong’s own design. He moved there in the twilight of his career, once he had built his fortune in armaments and shipping—two industries that were historically complicit with slaving and the slave trade in the Atlantic world, and that, by the 1870s, remained crucial actors in British imperial expansion and colonization.[43] It is possible that displaying images that had made appeals, respectively, to the immorality of Atlantic slavery in 1787 and to that of American slavery in 1853 was a strategy for Armstrong to distance his wealth from the more insidious associations it could potentially conjure to contemporaries. Although Armstrong had complained in personal correspondence that the “American difficulties” of the 1860s impeded his pursuits in the munitions business, his presentation of objects such as the column and the statue perhaps assured a more public image of his morality in a house that regularly welcomed royals, foreign dignitaries, and other prominent elites as guests.[44] Put differently, Armstrong’s display of antislavery imagery after abolition was no longer an urgent political matter in the Anglo-American world perhaps said more about his concern for his own persona than about individuals who had once been enslaved.[45]

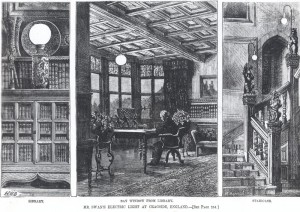

Accordingly, Armstrong’s installation of The American Slave at Cragside suggests that he meant the work to be seen and admired. The sculpture stood apart from the majority of the works of art in his collection, which occupied a gallery on the house’s second floor. Of the statues Armstrong owned, it was Bell’s he chose to install in arguably the most prominent and visible space in the house: a bespoke marble-inlaid niche on the main entry staircase (fig. 10). This oak staircase, fitted with ornately carved railings and electric light posts, had been a part of the architect Richard Norman Shaw’s expansions to Cragside in the 1870s.[46] Shaw’s designs for the entryway (1872; watercolor, ink and graphite on paper; inv. no. 13/5, Royal Academy of Arts, London) include a small recess for the niche, indicating that the staircase was planned with the sculpture’s display in mind. The statue thus appears on a landing halfway up the staircase beneath a set of family portraits, and opposite a second niche containing a marble sculpture of a crouching female nude (fig. 11).

The installation of The American Slave in this manner speaks to an effort to make visible the enslaved subject at Cragside, but it does so on a set of specific and controlled terms. Whereas the crouching marble statue opposite the landing seems cramped and crowded by its shallow, shorter recess, the overall height of the curved niche for Bell’s sculpture appears slightly overlarge, so as to dwarf the life-size figure and accentuate her guarded posture. To follow the geographer Neil Smith’s argument that scale distills “the oppressive and emancipatory possibilities of space,” the niche seems to emphasize the figure’s captivity.[47] Its base is elevated so that the silver chain corresponds directly to eye level, perhaps reminding viewers that the gripping fingers and tense wrists bound into stasis by its links belong to a body both responsive and resistant to the material constraints of enslavement. The surrounding space of the sculpture contains and orders.

Set into its niche, Bell’s statue stands out as a captive, anonymous, and raced body. The figure’s dark bronze materiality contrasts with the pale, ruddy skin in portraits of Armstrong and his kin, as well as the white marble surface of the statue opposite. In this familial space—originally ornamented with the Armstrong family standard as well as two watercolors of the estate grounds—an aesthetic of ownership emerges.[48] The installation suggests a gendered dynamic of property and paternalism not only between artwork and patron, but also of enslaved female subject and male head of household. In this architectural recess, the figure of the enslaved is literally and metaphorically subsumed into the order of the house—an act that could be as easily motivated by a desire to gaze at an exposed female body as by an ideological affinity for the histories of abolitionism.[49] Although Armstrong’s interest in The American Slave may have been inflected by antislavery ideology, his display of the work paradoxically threatened to reinscribe the dynamics of ownership of the system from which he sought to counter and distance himself.

An additional object in Armstrong’s collections is of final relevance here. He displayed on his library table at Cragside a large glazed cigar casket, encased in gilt rods representing sugarcane and supported at its corners by bronze polychrome statues of enslaved men (fig. 12).[50] Though each figure is distinct from the others in terms of age, expression, and clothing, the statues are not made to be beheld as individualized subjects (figs. 13, 14). Instead, their muscular bodies are rendered miniature and subservient in a manner not dissimilar from the small Wedgwood column that also stood in the room. The statues supporting the casket appear as personifications of different tobacco-producing regions of the Americas, recalling Renaissance imagery of the four continents personified, as well as eighteenth-century luxury wares such as sugar casters that incorporated sculptural representations of slaves (fig. 15). Each figure stands atop the casket’s blackwood base before a small label—“Maryland,” “Virginia,” “Havannah [sic],” and “Brazil,”—to visually and structurally reify the connection between commodities such as tobacco, sugar, and mahogany, and the slave-based labor at the core of their production.

Like The American Slave, the cigar casket appeared on prominent view in Armstrong’s home. When the periodical the Graphic ran a feature article about the electric lighting system at Cragside in 1881, the main illustration included with the text showed Armstrong seated at his library table, engrossed in writing and positioned to directly face the casket (fig. 16). A lamp hung from the ceiling illuminates the bent forms of the figures that support the box, whose bronze materiality is asked, by the image and its maker, to perform the work of reflecting white electric light in an article about modern technology and refinement.

Armstrong’s display of the cigar casket further complicates the question of how, why, and to what ends slavery was represented at Cragside. If Bell’s sculpture and the Wedgwood column were created as timely appeals against slavery, the casket seems to be a forthright endorsement of the exploitative labor conditions imposed on the men who produced commodities consumed in metropolitan homes before and after the abolition of slavery in the Atlantic and American worlds. Its presence in Armstrong’s collection further challenges the already-unstable nature of The American Slave as an object that stood at the often-contradictory crossroads of culture, commerce, and consumption.

Earlier versions of this project were presented at conferences at Tate Britain and at the Newberry Library. I am grateful to the organizers and participants of both events for their insights. I would like to thank Elizabeth Hutchinson, Martina Droth, and Michael Hatt for their invaluable feedback and suggestions; Adam Waterton, for his help with accessing images and archival material at the Royal Academy; and Florence Grant, for her expertise in the editorial process.

[1] On the visual culture of The Greek Slave in Victorian England, see Martina Droth, Jason Edwards, and Michael Hatt, eds., Sculpture Victorious: Art in An Age of Invention, 1837–1901, exh. cat. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014), 246–50, 306–27.

[2] John Bell to Henry Elkington, May 13, 1852, Elkington and Company Records, AAD/1979/3/1/8, 151–52, Archive of Art and Design, Victoria and Albert Museum (henceforth AAD).

[3] Ibid.

[4] The Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts, The Eighty-Fifth, 1853 (London: W. Cloves and Sons, 1853), 51.

[5] In correspondence with Elkington and Company from the early 1850s, Bell referred to his work in progress as The Negress Slave, but in an 1890 pamphlet of his works, he called the sculpture A Daughter of Eve. John Bell to Henry Elkington, May 13, 1852, 151–52; John Bell, Catalogue of Statuary by J. Bell, St. Mary Abbots, Kensington (London: Farmer and Sons, 1890), 5. The version of the statue at Cragside House is exhibited as The Slave Girl, and it has been referred to in scholarly literature by the titles A Daughter of Eve and the American Slave. For mentions of the sculpture as A Daughter of Eve, see Richard Barnes, John Bell: The Sculptor’s Life and Works (Kirstead, UK: Frontier Publishing, 1999), 49; Alison Smith, Exposed: The Victorian Nude (New York: Watson-Gupthill, 2002), 37; and Ingrid Roscoe, Emma Hardy, and Greg Sullivan, A Biographical Dictionary of Sculptors in Britain, 1600–1851 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 97. For mentions of the sculpture as The American Slave, see Michael Hatt, “The American Slave, 1853,” in Droth, Edwards, and Hatt, eds., Sculpture Victorious, 251–54, cat. no. 84. Consistent with this most recent literature, this essay will refer to the sculpture as The American Slave.

[6] Hatt, “The American Slave, 1853,” 251–54.

[7] On Bell’s depiction of the black female subject, see Hatt, “The American Slave, 1853,” 252; and Maurie McInnis, Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 200–202. On race and nineteenth-century sculpture, see Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997); Charmaine Nelson, The Color of Stone: Sculpting the Black Female Subject in Nineteenth-Century America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007); and Charmaine Nelson, Representing the Black Female Subject in Western Art (New York: Routledge, 2010), 105–21, 139–79.

[8] “The Eighty-Fifth Exhibition of the Royal Academy, 1853,” The Art Journal 5 (1853): 152.

[9] Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), xvii.

[10] Hatt, “The American Slave, 1853,” 251.

[11] A contemporary account of Elkington’s electrotype factory appears in “A Day at an Electro-Plate Factory,” Penny Magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, October 1844, 417–24. On the technology of electrotyping, see Angus Patterson, “The Perfect Marriage of Art and Industry: Elkingtons and the South Kensington Museum’s Electrotype Collection,” The Journal of the Antique Metalware Society 20 (June 2012): 56–77.

[12] Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 19.

[13] Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson, “Perpetual Returns: New World Slavery and the Matter of the Visual,” Representations 113, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 12, doi:10.1525/rep.2011.113.1.1 [login required]. See also Robin D. G. Kelley, “Burning Symbols: The Work of Art in the Age of Tyrannical (Re)Production,” in Hank Willis Thomas: Pitch Blackness (New York: Aperture, 2008).

[14] Eric Hopkins, The Rise of the Manufacturing Town: Birmingham and the Industrial Revolution (Thrupp, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing, 1998).

[15] Samuel Timmins, ed., The Resources, Products, and Industrial History of Birmingham and the Midland Hardware District: A Series of Reports, Collected by the Local Industries Committee of the British Association at Birmingham (London: Robert Hardwicke, 1866), vii.

[16] This economic activity has been overshadowed by modern scholarly focus on the region’s associations with abolitionist groups such as the Lunar Society and the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. Scholars have begun to complicate this picture by uncovering the extent to which the region was tied to global slave economies in terms of wealth accumulated and goods manufactured. Examples include Clive Harris, Three Continents, One History: Birmingham, the Transatlantic Slave Trade, and the Caribbean (Birmingham: Afro-Caribbean Millennium Centre, 2008); Andy Green, “Remembering Slavery in Birmingham: Sculpture, Paintings, and Installations,” Slavery and Abolition: A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies 29, no. 2 (May 2008): 189–201, doi:10.1080/01440390802027798 [login required]; and Marika Sherwood, “Britain, the Slave Trade, and Slavery, 1808–1843,” Race and Class 46, no. 2 (October 2004): 54–77, doi:10.1177/0306396804047726 [login required].

[17] Sherwood, “Britain, the Slave Trade, and Slavery, 1808–1843,” 54–77.

[18] Extract of a dispatch from Her Majesty’s Commissioners to Lord Palmerston, July 14, 1838, in The Third Annual Report of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (London: British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society with Thomas Ward and Charles Gilpin, 1842), 136.

[19] In the 1840s, Elkington explored the possibility of shifting their metal mining from Cornwall to the basin of the Rio de la Plata in South America, a region dependent on enslaved labor, but the English and French naval blockade of the river at this time stymied the project’s development. River Plate Agency to Henry Elkington, June 16, 1845, Elkington and Company Records, AAD/1979/3/1/1, 245, AAD; “Prospectus of the River Plate Steam Navigation Company,” Elkington and Company Records, AAD/1979/3/1/1, 251–52, AAD.

[20] Illustrations of Art Manufactures in the Precious Metals Exhibited by Elkington and Co. (London: Elkington and Company, 1873).

[21] Copeland and Thompson, “Perpetual Returns,” 8.

[22] Fred Wilson and Howard Halle, “Mining the Museum,” Grand Street 44 (1993): 157, doi:10.2307/25007622 [login required].

[23] Kay Dian Kriz, Slavery, Sugar, and the Culture of Refinement (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 3–4.

[24] Elihu Burritt, Walks in the Black Country and its Green Border-Land (London: Sampson, Low and Marston, 1868), 12.

[25] My thinking through the inter-medial nature of this sculpture is informed by Deborah Silverman’s research on the “violent technical procedures” deployed in crafting Belgian ivory and metal sculptures. She suggests that in certain luxury art objects, acts of physically manipulating and joining materials evoke and reinscribe the brutality of the colonial domination of bodies within the realm of the object. Silverman, “Art Nouveau, Art of Darkness: African Lineages of Belgian Modernism,” West 86th 18, no. 2 (Fall–Winter 2011): 146, doi:10.1086/668060 [login required].

[26] Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995), 4.

[27] For a discussion of the contested image and ideology of labor in nineteenth-century Britain, see Tim Barringer, Men at Work: Art and Labour in Victorian Britain (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005).

[28] Giovanni Arrighi, The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times (London: Verso, 1995). A discussion of Arrighi’s argument in relationship to the nineteenth-century British Atlantic appears in Ian Baucom, Specters of the Atlantic: Finance Capital, Slavery, and the Philosophy of History (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 34–38.

[29] Elkington and Company, International Exhibition Visitors’ Book, 1855–1878, MSL/1971/709, Special Collections, National Art Library, London. I am grateful to Angus Patterson, senior curator, Department of Sculpture, Metalwork, Ceramics and Glass, Victoria and Albert Museum, for facilitating my access to these books.

[30] Joseph Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), 30–31.

[31] Catherine Moulineux, Faces of Perfect Ebony: Encountering Atlantic Slavery in Imperial Britain (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 261–62; Kriz, Slavery, Sugar, and Refinement, 89–90.

[32] Walter Benjamin, “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century” [1935], in The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 82.

[33] George Wallis, “The Art Manufactures of Birmingham and the Midland Counties,” Midland Counties Herald, June 1862, quoted in Catalogue of Some of the Principal Pieces Exhibited by Elkington and Co.: Manufacturers of Artistic Works in Silver, Bronze, and other Metals: London International Exhibition, Class 33 (Birmingham: Elkington and Co., 1862), 11.

[34] On Armstrong’s career, see Henrietta Heald, William Armstrong: Magician of the North (Alnwick, UK: McNidder and Grace Limited, 2010) and Marshall Bastable, Arms and the State: Sir William Armstrong and the Remaking of British Naval Power, 1854–1914 (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004).

[35] Hatt, “The American Slave, 1853,” 254.

[36] For discussions of Armstrong’s collecting, see Dianne Macleod, Art and the Victorian Middle Class: Money and the Making of Cultural Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 219–34, 386–87; Paul Usherwood, Pre-Raphaelites: Painters and Patrons in the North-East (Newcastle upon Tyne: Laing Art Gallery, 1989); and Oliver Garnett, “‘Sold Christie’s. Bought Agnew’: The Art Collection of Lord Armstrong at Cragside,” Apollo 374 (1993): 253–58.

[37] Michael Hatt and Richard Barnes note that Seymour-Conway purchased the sculpture following the 1862 International Exhibition. Bell himself also mentioned the 4th Marquess’s purchase of the work in a pamphlet published in 1890. Curiously, the work does not appear in any of the collector’s sculpture or decorative arts inventories in the Wallace Collection Archives. However, it is interesting to note that Seymour-Conway contemplated buying the first version of The Greek Slave when it was auctioned in Paris during the summer of 1859. The correspondence surrounding this episode appears in John Ingamells, ed., The Hertford Mawson Letters: The 4th Marquess of Hertford to his Agent Samuel Mawson (London: Trustees of the Wallace Collection, 1981), 43. For Seymour-Conway’s purchase of Bell’s work, see Hatt, “The American Slave, 1853,” 253; Robert Wenley, “The Fourth Marquess of Hertford’s ‘Lost’ Collection of Sculpture,” Sculpture Journal 12 (2004): 84; Barnes, John Bell: The Sculptor’s Life and Works, 77; and John Bell, St. Mary Abbotts, Kensington, Catalogue of Statuary by J. Bell (London: Farmer and Sons, 1890), 5.

[38] Elkington and Company, Visitors’ Book, vol. 1 [showroom register], 1860–1867, 84, MSL/1971/708, Special Collections, National Art Library.

[39] Quoted in “The Story of the House of Elkington,” Goldsmiths Journal (May 1937): 129, in Elkington and Company Records, AAD/1979/3/1/10, AAD.

[40] Armstrong traveled to Egypt in 1872 to conduct research on hydraulics and recounted in lectures his disapproval for the enslaved labor he witnessed there. For an account of this visit, see William George Armstrong, A Visit to Egypt, in 1872. Described in Four Lectures (Newcastle upon Tyne: J. M. Carr, 1874), 30–32. See also Heald, William Armstrong, 176–77.

[41] Mary Guyatt, “The Wedgwood Slave Medallion: Values in Eighteenth-Century Design,” Journal of Design History 13, no. 2 (2000): 97–98.

[42] Macleod, Art and the Victorian Middle Class, 219–22.

[43] Marshall Bastable discusses the Elswick Ordnance Company’s (Armstrong’s company) involvement in British colonial projects in “Making the Global Arms Market, 1863–1914,” in Arms and the State, 109–146.

[44] William Armstrong to Margaret Armstrong, January 6, 1863, DF/A/11/18, Papers of the Lord Armstrong and Family of Cragside, Rothbury, Tyne and Wear Archives, Newcastle upon Tyne.

[45] In his important essay on Charles Cordier’s ethnographic portrait busts, James Smalls observes a similar phenomenon, of the image of the enslaved being mobilized for artists’ own political or personal interests, in the context of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century French work by Cordier, Jean-Antoine Houdon, and others. See Smalls, “Exquisite Empty Shells: Sculpted Slave Portraits and the French Ethnographic Turn,” in Slave Portraiture in the Atlantic World, ed. Agnes Lugo-Ortiz and Angela Rosenthal (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 283.

[46] Cragside, Northumberland (London: National Trust, 1983), 17.

[47] Neil Smith, Uneven Development: Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010), 230.

[48] Cragside, Northumberland, 17.

[49] Many scholars have discussed the sexualization of the enslaved female body in European and American art. See especially Hatt, “The American Slave, 1853,” 254; Smalls, “Exquisite Empty Shells,” 304–7; Nelson, The Color of Stone; and Joy Kasson, Marble Queens and Captives: Women in Nineteenth-Century American Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 51–55.

[50] “Electric Lighting by the Swan System at Sir William Armstrong’s Residence, Cragside,” Graphic, April 2, 1881, 332. Little is known of the maker or provenance of this cigar casket, presently in the collections of the National Trust at Cragside. It composed part of Armstrong’s original collection and was likely given to him as a gift. Close observation of the casket’s underside and blackwood base reveals no visible foundry marks or hallmarks. However, its 1881 appearance in the Graphic situates it firmly within the nineteenth century.