The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

On December 15, 1843, the man who would become Hiram Powers’s most distinguished private patron visited the artist’s studio for the first time.[1] Anatole Demidoff, Prince of San Donato, one of the greatest collectors of the age, had come to see for himself the work of the much-talked-about American sculptor in Florence.[2] For Powers (1805–73), the visit by such a notable person would have been cause for excitement at any time, but at this moment it held special promise. Although Powers’s creative energy was at a high point, the state of his finances was precarious. He had orders for scarcely a half-dozen portrait bust commissions and none for a statue of an ideal subject. He was seriously considering abandoning his career and returning to his home in Cincinnati, Ohio.[3] Prince Demidoff had a taste for contemporary marble sculpture. He admired the nearly finished plaster model of The Greek Slave and saw the marble block that was already being prepared—no version had yet been carved—but to Powers’s great disappointment, he left without placing an order. It was not until six years later, in 1849, that Demidoff ordered what would be Powers’s fifth marble version of the original plaster, giving it a context unlike that of any other.

Anatole Demidoff was born in 1812 in Saint Petersburg, the son of Nicolas Nikititch Demidoff (1773–1828) and Baroness Elisabeta Alexandrova Stroganova (1779–1818). His family had amassed a vast fortune over a hundred years, through their business as ironmasters and suppliers of weaponry to the imperial armies, and by their ownership of silver mines in the Urals and rich veins of malachite on their estates. Anatole inherited a passion for art from his grandfather and, more immediately, from his father, who was a collector and arts patron. Nicolas had married into the aristocracy and after the defeat of Napoleon (whom he supported) in 1812 and the restoration of the monarchy, had moved his estates and his young family to Paris. Following the death of his wife in 1818, he moved to Italy, settling briefly in Rome and then in 1822 in Florence, where he founded hospitals and other charitable institutions. In a decision that would be of profound significance for his descendants, he bought forty-two acres of marshy land at San Donato in Polverone outside the city, and commissioned from the architect G. B. Silvestri a great villa, which he proceeded to fill with a stunning collection of paintings by old masters, sculptures, and furniture. Impressed with Nicolas’s philanthropy, Leopold II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, rewarded him with the title of Count of San Donato.[4]

In 1828, Nicolas died suddenly, and sixteen-year-old Anatole, who had been educated principally in Paris, immediately set about to make himself known in that city and then in Florence.[5] He commissioned a life-size equestrian portrait of himself in national costume from the Russian painter Karl Bryullov, who was living in Florence (fig. 1). Such a dashing pose and grand scale would have been unusual for a portrait of anyone other than a member of the royal family or a famous military hero. Supremely confident, Demidoff began to build a reputation as a patron of contemporary art. At twenty-two years of age, he bought two of the most celebrated pictures in the 1834 Paris Salon—The Execution of Lady Jane Grey by Paul Delaroche (1833, oil on canvas, National Gallery, London) and François-Marius Granet’s Death of Poussin (1834, oil on canvas, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Reims). He continued to develop the villa at San Donato, greatly increasing its scale. By the time it was completed, it was unlike any Tuscan villa (fig. 2). The principal salon was three stories high, surmounted by a dome and lined with ribs of malachite. At the center, “a grand, semi-circular portico of arches supported by Doric columns led into the entrance hall. . . . In the grounds near the house were situated . . . an ‘Odeon’ for the performance of music and plays; further away were temples, fountains, a magnificent collection of orchids blooming in immense greenhouses and a zoo with such exotic creatures as ostriches and kangaroos.”[6] The flamboyant Demidoff’s enormous wealth allowed him to gratify any interest, whether its object was animate or inanimate. He built on his father’s collection of old masters, making his mark as a collector of Dutch and Flemish pictures when still a very young man by buying thirteen important paintings at the 1837 sale of the Duchess of Berry’s collection.[7] He followed enthusiasms of his own, especially for the decorative arts of eighteenth-century France and objects de vertu with historical associations,[8] and commissioned paintings from Eugène Delacroix (a favorite) and watercolors from Richard Parkes Bonington, Théodore Gericault, Eugène Louis Lami, and Auguste Raffet.[9]

On November 1, 1840, Anatole Demidoff married Mathilde (1820–1904), the twenty-year-old daughter of Jérôme Bonaparte, Prince of Montfort (youngest brother of Napoleon), who was living in exile in Florence with his second wife, Catherine, Princess of Würtemburg. Mathilde and her brother were the first members of the Bonaparte family to be born of royal blood: Czar Nicholas I and King George III were their uncles. Mathilde was among the most cultivated members of the family and would later become a renowned patron and friend of the greatest French writers of the day. The marriage brought advantages to both parties—fabulous wealth to her, increased social status to him. His position was further solidified when the Grand Duke of Tuscany nominated him to become the first Prince of San Donato. The newlyweds honeymooned in Russia, where Mathilde’s charm went far to appease Nicholas I, who strongly disapproved of Demidoff’s extravagant life abroad and periodically threatened to withhold income from his Russian estates.[10]

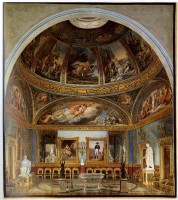

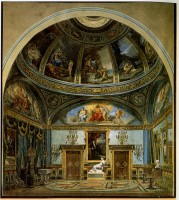

The glamorous young couple shared a knowledgeable and passionate interest in art and held glittering soirees in the sumptuously decorated salons of the Villa Mathilde (as Demidoff now called the Villa San Donato). Two paintings by Fortuné Fournier depict the ballroom surmounted by a large dome covered in frescoes of the story of Cupid and Psyche by the modern Roman painter Carlo Morelli, and reveal the presence of a copy of Antonio Canova’s statue of Letizia Bonaparte (“Madame Mere”) made for Demidoff’s father-in-law (figs. 3, 4). But by 1843, the marriage was in trouble. Demidoff resented Mathilde’s greater popularity, and both parties began to look elsewhere for amorous distractions. Their relationship was made even more unhappy by signs of syphilis, which would further develop fifteen years later. For a time, however, the couple maintained appearances in public. In the summer of 1845, Demidoff visited Powers’s studio and commissioned a bust of his wife (fig. 5).[11] By the time the bust was delivered in March 1847, Princess Mathilde had already divorced her husband and moved with her lover to Paris, where she became the center of a brilliant literary salon. Neither one ever remarried.[12]

In 1845, The Greek Slave was shown in public for the first time in London; further versions were toured in the United States from 1847, as Tanya Pohrt and Cybèle T. Gontar discuss in their articles. The statue garnered intense reactions. Word of the response to “this World Renowned Statue over which poets have grown sublime, and Orators eloquent,” as one of the handbills described it, undoubtedly reached the art world of Florence.[13] Perhaps regretting that he had not purchased the first version when he had had the chance six years before, Prince Demidoff signed an agreement on September 8, 1849, for the partially finished version that Powers had originally intended to turn over to Sidney Brooks, his American banker, for possible sale for the artist’s benefit. Demidoff contested the price but finally agreed to pay seven hundred pounds, of which four hundred was to be paid immediately and the balance, upon delivery of the finished statue on May 1, 1850. But he elected to make his payments in equal monthly installments beginning in January and ending in July 1850, which meant he would have the statue in his possession before the last payment had been made, a privilege not extended to Powers’s other clients. Demidoff’s Greek Slave follows closely the style and execution of the first version (Raby Castle, Staindrop) but the drapery has fewer tassels and includes coarser fringe (fig. 6). In a separate agreement, Demidoff ordered an elaborate white marble pedestal, ornamented with arabesques in low relief, on which to display the statue. Powers had originally suggested a base in colored marble, and sketches were sent to Demidoff on November 2, 1849.[14] It seems possible that the existing pedestal, with its elegant intertwining of leaves and scrollwork executed in low relief, was made after the design requested by Demidoff, but there is no record in the Powers archive to prove the connection.[15] On May 1, 1850, as promised, the statue and pedestal were delivered to Villa San Donato.

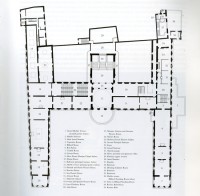

We do not know where in the villa The Greek Slave was installed, only that Demidoff considered her important enough to place her in a room by herself.[16] What we do know is that this figure of grace and pathos entered an opulent, cosmopolitan setting. Life at San Donato was devoted to the pursuit of art and pleasure. Demidoff entertained lavishly (he even had an elaborate chicken dish named in his honor). The word “villa” does not do justice to what was, in effect, an urban palace transferred to the countryside. While the furnishings, decorations, and porcelain collections reflected a taste for the ancien régime and Empire periods, the full range of Demidoff’s artistic interests was staggering. A floor plan (based on those found in contemporary guidebooks) shows individual spaces named after their principal contents (fig. 7). These included the Tapestries Room, Turkish Room, Greuze Room, and Flemish and Dutch Pictures Room; auction records show he owned paintings by Rembrandt van Rijn, Peter Paul Rubens, Jacob van Ruisdael, Aelbert Cuyp, Meindert Hobbema, Gabriel Metsu, Hans Memling, and other great masters. There was a Boucher Room and an Ivories and Spanish Pictures Room, which contained paintings by Bartolomé Estebán Murillo, Jusepe de Ribera, and Francisco de Zurbarán, as well as Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Philip IV (ca. 1656, oil on canvas, National Gallery, London) and an assortment of Chinese vases. The Luca Giordano Room, Arab Room, Mosaics and German Pictures (with works by Lucas Cranach), and Modern French Pictures Gallery also appear on the plan. Among the modern French pictures was Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Antiochus and Stratonice (1840, oil on canvas, Musée Condé, Chantilly), which Demidoff bought from the collection of the late Duke of Orleans, the son and heir of King Louis-Phillippe. He owned major Venetian pictures by Jacopo Tintoretto, Titian (The Duke of Urbino and His Son, location unknown), and Paolo Veronese (La Belle Nani, ca. 1560, oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris), and an altarpiece by Carlo Crivelli (ca. 1470, oil on wood panels, National Gallery, London). Like many other collectors of his day, Demidoff was more interested in modern than in Renaissance sculpture, and in Italian rather than French works. He owned work by Giulio Tadolini, Lorenzo Bartolini, Raffaello Romanelli, Félicie de Fauveau, and Giovanni Duprè, among others, as well as the erotic sculptures of the Swiss-born James Pradier (for example, Satyr and Bacchante, ca. 1834, marble, Louvre, Paris).[17] While some of the earlier versions of The Greek Slave had been sent on tour for profit in public exhibitions, Prince Demidoff acquired the statue solely for his own viewing pleasure, and that of his private guests.

Outside the Villa San Donato, there was political turmoil. The revolution of 1848, which had begun in Paris with the deposition of King Louis-Philippe, had spread to Italy. The Italian nationalist general Giuseppe Garibaldi, an ardent republican who fought to secure the unification of Italy, had recently given up trying to hold Florence against the Austrian army and had continued north. Inside the villa there was no support for the cause. Prince Demidoff was neither a liberal nor a fan of the Risorgimento. During times of Austrian oppression he remained on friendly terms with the occupying troops.[18] There is nothing to suggest he had sympathies for the American abolitionist cause. We can more easily imagine him accompanied by the young actresses whose company he favored, strolling with his guests from one splendid salon to another, sipping champagne, and stopping to enjoy his latest acquisition—The Greek Slave, a suggestive and sentimental sculpture based on the Hellenistic Venus de Medici, which they all would have known at the Uffizi. Gathered around her, they may have compared her to the ancient model, arguing the artistic merits of each. The American sculptor had added a political narrative to the famous figure, calling forth in the viewer a mixed shiver of pity and voyeurism. Unlike her proudly sensual ancestor, Powers’s nude was a tragic figure, shamed by her unclothed body. Here in the Villa San Donato, The Greek Slave, perhaps like the ancient goddess of love before her, was, above all, an object for the male gaze.

In 1859, the Grand Duke of Tuscany was expelled by a bloodless coup just before the Second Italian War of Independence. Florence was annexed by the kingdom of Sardinia and placed under the rule of the soldiers of King Victor Emmanuel II. Demidoff, who had been on terms of genuine friendship with the Grand Duke, felt that the time had come for him to leave Tuscany and return to France. He closed the Villa San Donato but continued to send pictures there from time to time, hoping that the old order would soon be restored. But he was seriously ill, his syphilis taking a stronger hold. Realizing perhaps that his life was coming to an end, he decided to empty the villa of most of its treasures. It was the end of an era. Paintings, watercolors, sculptures, porcelain, ceramics, furniture, silverware and costumes, arms and armor, gold boxes, miniatures and jewels, many originally created for royal patrons and their courtiers, and all now having gained additional luster through their connection with Demidoff, were stripped from fourteen rooms in San Donato and sent to Paris for sale at auction. The first of the ten auctions was held in 1863, followed by sales in 1868 and 1870.[19] They garnered huge publicity and huge prices. Treasures from San Donato were soon found in major public and private collections in Europe, and later in America. The Greek Slave (lot 226) was sold to the London dealer Phillips in the sale of March 3–4, 1870, for 53,000 francs (about $11,000). It was a record price for a modern piece of sculpture on the Paris auction block.[20]

On April 29, 1870, the day after the last of these history-making sales, Prince Anatole Demidoff died in Paris. He was fifty-eight years old.[21] After passing through various private ownerships, the Demidoff Greek Slave was acquired by the Yale University Art Gallery in 1962 where, for the first time in the sculpture’s history, it has been on public exhibition.

[1] Richard P. Wunder, Hiram Powers: Vermont Sculptor, 1805–1873, 2 vols. (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1991), 1:211.

[2] Francis Haskell, “Anatole Demidoff and the Wallace Collection,” in Francis Haskell, Stephen Duffy, Robert Wenley, and David Edge, Anatole Demidoff, Prince of San Donato 1812–70, Exhibition of Works of Art Now in The Wallace Collection Formerly Owned by Anatole Demidoff, exh. cat. (London: Trustees of the Wallace Collection, 1994).

[3] Wunder, Hiram Powers, 1:136.

[4] Haskell, “Anatole Demidoff,” 10.

[5] To honor their father, Anatole and his brother commissioned a huge marble monument from the leading sculptor in Florence, Lorenzo Bartolini. Begun in 1830, it was not completed until 1870, after years of acrimonious negotiation about its form and placement. Today, the Monument to Count Nicolas Demidoff sits in the Piazza Demidoff, Florence.

[6] Haskell, “Anatole Demidoff,” 12.

[7] Stephen Duffy, “Seventeenth-Century Dutch and Flemish Paintings,” in Haskell et al., Anatole Demidoff, 50.

[8] Haskell, “Anatole Demidoff,” 20.

[9] Stephen Duffy, “Nineteenth-Century Paintings,” in Haskell et al., Anatole Demidoff, 35–36.

[10] Haskell, “Anatole Demidoff,” 18. In 1837–38, largely seeking approval from Czar Nicholas I, who considered him an arrogant upstart and strongly disapproved of his lavish life abroad, Demidoff organized and funded an expedition to the Crimea and South Russia, which was made up of twenty-two French artists, journalists, scientists, and archeologists. Various publications resulted from their travels, the most significant of which was Voyage dans la Russie Meridonale et la Crimee in six volumes, with one hundred original lithographs by Auguste Raffet, dedicated to the czar and published between 1840 and 1848. Demidoff financed other expeditions, and in 1842 he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

[11] Wunder, Hiram Powers, 2:32, cat. no. 25. In 1846, Demidoff commissioned a bust of the Grand Duchess of Tuscany, intended as a gift to the sitter (Wunder, Hiram Powers, 2:22, cat. no. 10); in 1851, he ordered a replica of the Fisher Boy (Wunder, Hiram Powers, 2:147, cat. no. 176). Powers appears to be the only American artist represented in the Demidoff collection.

[12] Wunder, Hiram Powers, 1:144. Demidoff kept the bust of Princess Mathilde throughout the rest of his life. The piece passed to his heirs and was not shown in public until the 1980s, when it came on the art market.

[13] Reproduced in Wunder, Hiram Powers, 1:251. The handbill was distributed during the tour of The Greek Slave, when the statue was on exhibition in New Haven, Connecticut, in July 1851.

[14] Wunder, Hiram Powers, 2:166, cat. no. 5.

[15] Wunder, Hiram Powers, 1:271n200.

[16] “Powers the Sculptor,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 8 (November 1850): 137.

[17] Haskell, “Anatole Demidoff,” 24. Haskell suggests that most of these sculptures, as well as the paintings Demidoff bought from contemporary Florentine artists, “were essentially used for decorative purposes rather than to be displayed in their own right.”

[18] Haskell, “Anatole Demidoff,” 25–26.

[19] Haskell, “Anatole Demidoff,” 26–27. For the extent of the collections at auction, see Collections de San Donato: tableaux, marbres, dessins, aquarelles et miniatures (Paris: Charles Pillet, 1870), accessed January 15, 2016, https://archive.org/details/collectionsdesa00pillgoog.

[20] Wunder, Hiram Powers, 1:342.

[21] Demidoff is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery. His nephew and heir, Paul Demidoff, the second Prince of San Donato, was also an extraordinary collector and restored the villa to much of its former glory. But in 1880, he stripped it of most of its paintings and furnishings, selling them in an even more sensational sale than those of his uncle ten years earlier. Villa San Donato remained empty for six years before it was acquired by a Russian princess, who kept it until the revolution of 1917. Thereafter it was neglected and left to ruin until it was finally demolished in 1945. For a sense of the magnitude of the Paul Demidoff collections, see the following articles by James Jackson Jarves: “Prince Demidoff’s Sale,” New York Times, February 1, 1880, accessed January 15, 2016, http://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1880/02/01/98883368.html [login required]; “Prince Demidoff’s Matchless Collection,” New York Times, March 25, 1880, accessed January 15, 2016, http://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1880/03/25/98891386.html [login required]; and “The Demidoff Art Collection Sale,” New York Times, May 8, 1880, accessed January 15, 2016, http://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1880/05/08/98898763.html [login required]. See also “Prince Demidoff and the San Donato Sale,” Art Amateur 2, no. 5 (April 1, 1880): 98–99, accessed January 15, 2016, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25627067 [login required].