The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

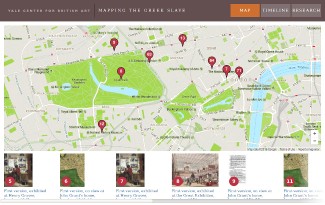

This essay accompanies a digital interactive that tracks the exhibition and ownership history of The Greek Slave, from the plaster model through the six marble versions Hiram Powers (1805–73) produced between 1843 and 1866. The sum of these histories is a story of mobility, a decades-long journey that was set in motion in Italy and took many different paths across Europe, England, and North America. Unlike most of the content in this special issue, the digital interactive primarily offers information rather than interpretation. It presents historical sources that allow us to track the movement of each Greek Slave from the date of its completion, showing the routes it traveled, the venues where it was displayed, each time and place it was bought and sold, and the ways in which its reputation, fame, and value changed along the way. Although exhibition and provenance histories of the six statues have been published before, notably in Richard P. Wunder’s catalogue raisonné of 1991, much new material—and more accurate empirical data—has been uncovered since.[1] The present project has assembled a clearer and more complete picture by drawing upon the huge digital databases of primary resources that are now available to researchers and reproducing a selection of these documents in the interactive.[2] This project, then, could only be published on a digital platform.

“Mapping The Greek Slave” digital interactive, 2016: research and content by Martina Droth; editorial implementation and additional research by Sarah Kraus; technical support by A. Robin Hoffman and Michael Appleby; platform design by Night Kitchen Interactive.

How to cite this digital interactive:

Martina Droth with Sarah Kraus, “Mapping The Greek Slave” digital interactive, in “The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers: A Transatlantic Object,” eds. Martina Droth and Michael Hatt, special issue, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 15, no. 2 (Summer 2016), http://interactive.britishart.yale.edu/mapping-the-greek-slave/map.

Recommended browsers:

Google Chrome (Windows, OS X); Internet Explorer 10 & 11 (Windows); Firefox 24+ (Windows, OS); Safari 6+ (OS X). Content may not display correctly if other combinations of browsers and operating systems are used.

In what ways does this aggregation of data provide a new or more nuanced picture of The Greek Slave? One advantage of the digital interface is that it allows us to take different slices through the information—geographically on a map, and chronologically on a timeline. Equally, it enables the visual presentation of large quantities of original documentation. Names and places can be attached to their historical sources (illustrations, photographs, news reports, advertisements, letters, etc.), and these sources, in turn, begin to reveal contexts: for example, the nature of exhibition venues, the circumstances of sales, and the rise and fall in values. Of course, this is still a partial picture, but one that leads in productive directions. In the following essay I will draw out some of the ways in which the digital interactive can open new avenues of inquiry, and indicate how these might contribute to our understanding of this object and of our study of sculpture more broadly.

The Marble Statues

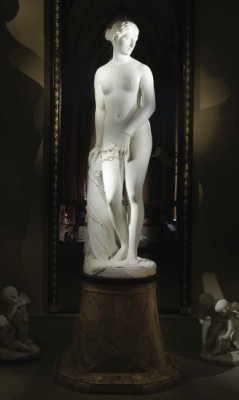

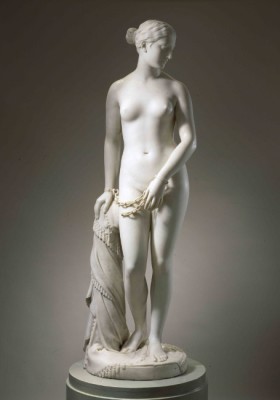

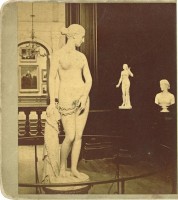

The digital interactive “Mapping The Greek Slave” focuses on the six marble versions of the statue (figs. 1a–1f). It is not a timeline of Hiram Powers, or of the historical and political events that hover in the background. Making a timeline that pulls the object out of context prompts attention to the statue itself, thereby highlighting a key point: that from the 1840s to the present, The Greek Slave was persistently visible on both sides of the Atlantic. This may not sound like news; but it shows that in an era of mass and mechanical reproduction, it was not only the flattened and reduced forms of photographs, prints, statuettes, and souvenirs that ensured the circulation and dissemination of The Greek Slave, but also the production of multiple, full-scale marble statues. Replicated with mostly minor variations six times in the studio, the statue was instrumental to its own visibility: Powers too knew how to harness technologies of multiplication. His precise, carefully engineered marble reproductions ensured that the figure was the superlative agent of its own fame. Far from becoming a merely passive subject of reproduction—an absent object endlessly refracted into more-or-less distant echoes of itself—it asserted its own multiple presence. Like clones, the marble statues generated from the single model allowed The Greek Slave as an original work to be present simultaneously in many places and across vast distances. Far from diminishing the effect and import of the statue, its very multiplicity served to enhance its aura.

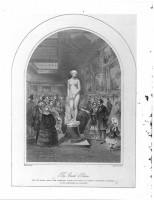

All this matters, first and foremost, because it reminds us that each Greek Slave is a sculpture. The status and presence of these works as sculptures were important to audiences and hence form part of their history. In common with other white marble statues, The Greek Slave was innately linked to the classical ideal of ancient Greece, considered the most exalted of artistic traditions. Today it may appear to conform to this tradition all too well; but for nineteenth-century viewers it was a daring manipulation of classical conventions. The ideal served not so much as a template for imitation than as a concept for exploring modern ideas. The Greek Slave’s chains and subject—a woman enslaved during the Greek War of Independence, which had only ended recently, in 1832—held the figure in tension, between the imagined, ancient past and the modern world. The skillfully wrought chains, fully freed from the marble block, even in the narrow space behind the left hand, disrupted the fantasy (fig. 2). As one commentator put it, Powers offered the “highest idealized conception of female loveliness” only to “pull down our fancy” back to earth: “The chain and manacles, when the eye does steal a glimpse of them, produce strange contrarieties of feeling and emotion” (fig. 3).[3]

The subject and the marble object instrumentally informed each other. Commentators referred to the figure’s convincing anatomy, the flesh-like limbs and surfaces; the “wrinkles of the smallest joint” were noted, the “porosities” and “fugitive movements of the skin,” as though more perfectly skin-like than skin itself: “No most delicate skin is more delicate than the surface of his marble.”[4] The fantasy of an inner life residing dormant in the marble body tipped the sculpture, Galatea-like, into the realm of uncanny illusion, making its subject all the more potent and complex. This same fantasy underpins the numerous articles that anthropomorphized the statue and imagined it to speak (fig. 4).

In contrast, much of the scholarship in the past few decades has dematerialized The Greek Slave into its iconography. The enormous and sustained interest in the statue revolves around its multivalence as an image, not its intrinsic sculptural qualities. The primary context in which we encounter the statue today is the history of slavery, abolition, and the American Civil War. The priority for scholars has been to sift through the vast quantities of text and images that the statue generated as a way of evaluating changing responses to slavery. Since these responses proliferated mainly on the flattened space of the page, they seem themselves to prioritize the image. Images can begin to appear not only as sufficient for analysis but also as potentially more important than the statue—they seem to say that the figure was already dematerializing at the time of its circulation.

It is important to acknowledge that historians’ use of The Greek Slave as image, icon, and subject has made a necessary intervention: it has given this work an extraordinary currency, unmatched by any other sculpture of the time. Had it not been adopted into fields of study beyond sculpture and beyond art history, it would likely have faded away, like so many other statues relegated as “neoclassical sculpture.” But the nature of this attention creates a conundrum, for it means the importance given to The Greek Slave is only oblique; essentially, it is a tool, or channel, to get at other subjects. If anything, its significance seems to recede when regarded head-on as sculpture. Indeed, as a sculpture it appears so much less remarkable, even utterly conventional. Thus while the figure’s phenomenal appeal for nineteenth-century audiences has provided rich insights onto a critical historical moment, its popularity has nevertheless mystified some scholars.

I want to make two points here: First, there is a major problem with prevailing conceptions of “neoclassical sculpture,” a phrase which seems to serve no purpose other than filing away a type of sculpture that is of virtually no interest to scholars today. Its careless application has effectively resulted in invalidating a massive tranche of nineteenth-century art production, which at the time, however, was seen as the epitome of high aesthetics. The Greek Slave, in its undeniable, irrepressible importance, has sidestepped the problem—it has escaped the category, or rather, has allowed scholars to ignore the fact that it is part and parcel of a tradition of sculpture now generally seen as irrelevant. Second, although forgetting about the sculpture tradition has unquestionably been a useful strategy for dealing with the rich history of The Greek Slave, it has also resulted in reducing the figure to a single, interpretative dimension. But The Greek Slave was and is a sculpture. It was not conceived as an image or an illustration of a moral point, nor was it regarded as such. The responses it elicited rippled out as much from the marble statue as from its subsequent, uncontrollable circulation in myriad reproductive forms. The statue therefore opens an opportunity to reconsider the role and significance of sculpture, and our conceptions of sculpture of its kind. For historians primarily concerned with sculpture as much for those who are not, The Greek Slave offers some important lessons for widening the purviews of our fields.

Exhibitions of The Greek Slave

The digital interactive “Mapping The Greek Slave” expands the known exhibition histories of The Greek Slave and shows that Powers’s strategies of multiplication and dissemination made this one of the most widely displayed and traveled sculptures of its time. Although some gaps and questions remain, the digital interactive provides details that inflect what we know of the statue’s reception and audiences. Several important considerations are brought to light in the process: The Greek Slave was on almost continuous display from 1845 onwards, both in England and North America; its fame did not originate in, and indeed extended well beyond, its display at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in London in 1851, an event that is often seen as the defining moment for the statue’s reputation. The character of the venues was diverse; modes of display varied greatly and were often determined by ownership. By the same token, there was a gradual but increasingly dramatic shift in display conventions. In sum, the exhibition histories of The Greek Slave reveal that each statue was deeply and inextricably conditioned by the circumstances of its physical placement.

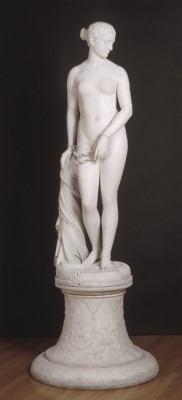

The visibility of The Greek Slave was purposefully orchestrated by Powers in the early years, and surely owed something to his background in the entertainment industry. Prior to his move to Florence in 1837, he had worked for the showman Joseph Dorfeuille at the Western Museum in Cincinnati, making scenery and mechanical figures for popular shows. As a sculptor, he had the canny foresight to prioritize the public display of his work, negotiating its availability with his patrons, and even rescinding or delaying sales if it meant a statue could be shown. This is evident from the very outset, when Powers sold the first version of The Greek Slave (1844, Raby Castle, Staindrop) to Captain John Grant, an Englishman based in London (fig. 5). Grant supported Powers not only through commissions, but also by ensuring the successful public presentation of The Greek Slave. Upon its shipment to London in 1845, its destination was not Grant’s private residence, but the public rooms of the print publisher Henry Graves for Powers’s inaugural exhibition.

Letters in the Archives of American Art record extended discussions between Grant and Powers about the choice of venue. While cognizant of the prestige of the Royal Academy, they rejected the sculpture room as unworthy of the statue: “I never had an idea of allowing ‘the Slave’ to be exhibited in such a small, dark, dingy hole,” Grant wrote in August 1844.[5] The choice of Graves was partly due to the delayed shipment of the statue (in May 1845), too late in the exhibition season, Grant explained, for the “public galleries,” and partly due to Grant’s preference for “the higher class of people and patrons of art” that made up Graves’s clientele.[6] No images have come to light of the statue’s display at Graves, but letters by Grant reveal that he had its rotating pedestal covered in maroon cloth, the floor carpeted in the same color, and a protective railing installed in front; he was also constructing a “circular screen” to be suspended from the ceiling, so that a curtain could be raised and lowered to cover or reveal the statue as needed.[7] The dramatic presentation paid off; in October 1845, Grant was gratified to tell Powers that “upwards of 40,000 persons” had viewed the statue.[8] Given how much attention the statue garnered at Graves, it is surprising to find that its display was no solo affair: one review reveals that it shared the stage with a statue of a nymph by William Theed II.[9] On the one hand, this detail underlines Powers’s success, since Theed’s statue barely warranted a mention; on the other, it reminds us that The Greek Slave was a sculpture among sculptures, and that its primary subject, a nude female body, took its place amid others.

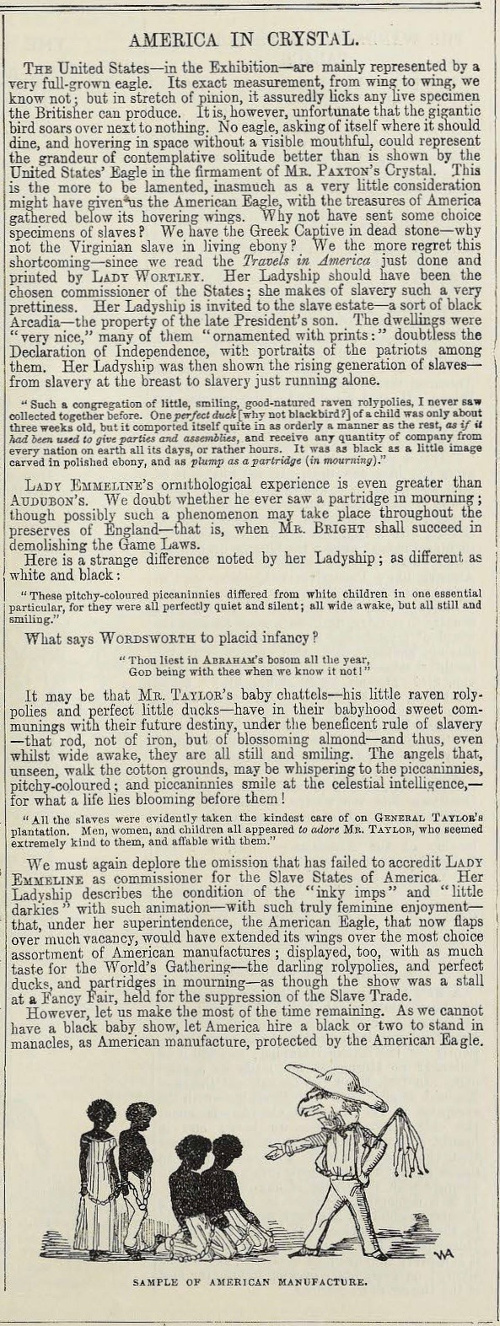

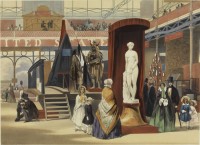

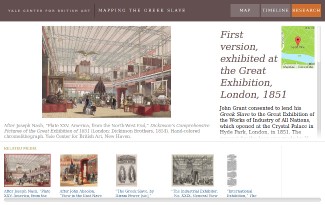

Grant’s description of the statue’s display at Graves brings to mind the famous red-curtained canopy that surrounded it at the Great Exhibition in 1851, and was captured in numerous illustrations (fig. 6). Published letters in the Times record that Grant consented to lend the statue to the American section, asking to be allowed to oversee its safe installation.[10] This request may indicate that he continued to exert some influence in how the display was curated. But if he helped stage-manage the display, the Great Exhibition was beyond any curatorial control he may have wished to exert. While the art-oriented space of Graves attracted chiefly an art-critical response, the Great Exhibition exposed The Greek Slave to a context not primarily about art, and a much larger and more socially diverse audience. Standing in this palace of industry, The Greek Slave was drawn into general assessments of what America had put on show to the world: the statue became a specimen of America’s national produce. The national emphasis of the setting, and the exhibition’s overarching purpose to present the “works of industry of all nations,” had the effect of making The Greek Slave contentious. Although the statue’s allusion to the American slave trade had been mooted at an earlier date,[11] it was brought to the fore at the Crystal Palace and became an indelible association. A column in Punch illustrates the way in which context inflected meaning (fig. 7). Titled “America in Crystal,” the column asked, “Why not have sent some choice specimens of slaves? We have the Greek Captive in dead stone—why not the Virginian Slave in living ebony?” It ended with an illustration of America personified as an eagle (a reference to the massive eagle-emblem that hovered over the pavilion) standing with a cat-o’-nine-tails before four chained slaves; the second figure from left is pictured in a pose reminiscent of The Greek Slave’s. The caption reads: “Sample of American Manufacture.”[12]

Images of the American section of the Great Exhibition consistently depict The Greek Slave in its red canopy and on the same rotating pedestal as before (on which this particular version still stands today). The Greek Slave appears as the eye-catcher of the court, but it is not shown in isolation. The eagle always hovers above; and often depicted on the ground behind is a raised platform offering a display about “extinct tribes of Red Indians,” complete with teepee and life-size mannequins in native dress (fig. 8).[13] The display was extracted from George Catlin’s famous Indian Gallery, which had been shipped at great expense to England but failed to become the lucrative attraction Catlin had hoped.[14] Although Catlin’s 1851 exhibit did not include living people, we know that in the 1840s he had taken individuals from Ojibwe, Fox, and Iowa tribes to London to perform war dances and wedding ceremonies for paying audiences at the Egyptian Hall (fig. 9), the same venue in which William Ward, 1st Earl of Dudley, placed his Greek Slave in (1847, fourth version, location unknown) the 1850s.[15] At the Great Exhibition, Catlin’s display appears to have garnered little attention, only becoming newsworthy when it was attacked and partially destroyed by a drunken woman.[16] Similarly, in images of the American section, the display is rarely depicted with any clarity. There seems to be a deliberate dynamic between these receding, muted figures in the background, and Powers’s distinctly marked-out, ideal, white statue defining the foreground. Each is associated with the past as well as the present: on the one hand, a timeless classical past reborn in a modern and divisive subject; and on the other, a precolonial past that was romanticized while depicted as succumbing to the advances of civilization. Perhaps this scene, as a marker of America, suggests a sense of destiny and inevitability.

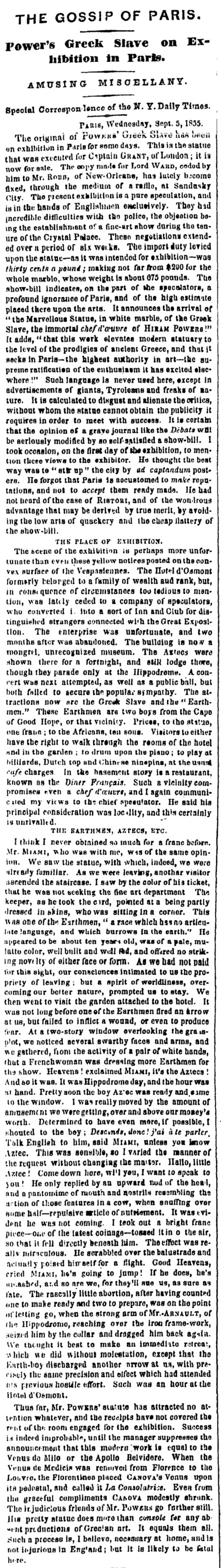

Notwithstanding the moral outrage The Greek Slave was capable of eliciting, its juxtaposition with morally questionable human displays was nothing out of the ordinary. In 1855, John Grant reportedly permitted his statue to be put on exhibition in Paris for profit, a venture that, newspapers said, was a miscalculated failure.[17] The location was the Hôtel d’Osmont, formerly a luxurious aristocratic residence but by mid-century in use for entertainments.[18] Here The Greek Slave was placed alongside a show of “the Aztecs” and “the Earthmen” from Africa, spectacles of human curiosity that entailed the transportation of individuals from faraway countries to European cities (fig. 10).[19] The displays were staged in different rooms, and entry was by separate ticket (“Prices to the statue, one franc; to the Africans, ten sous”).[20] Nevertheless, the juxtaposition equated statues and humans as objects for a particular kind of viewing, in that both possessed a presence that blurred the boundaries of what nineteenth-century spectators counted as human.

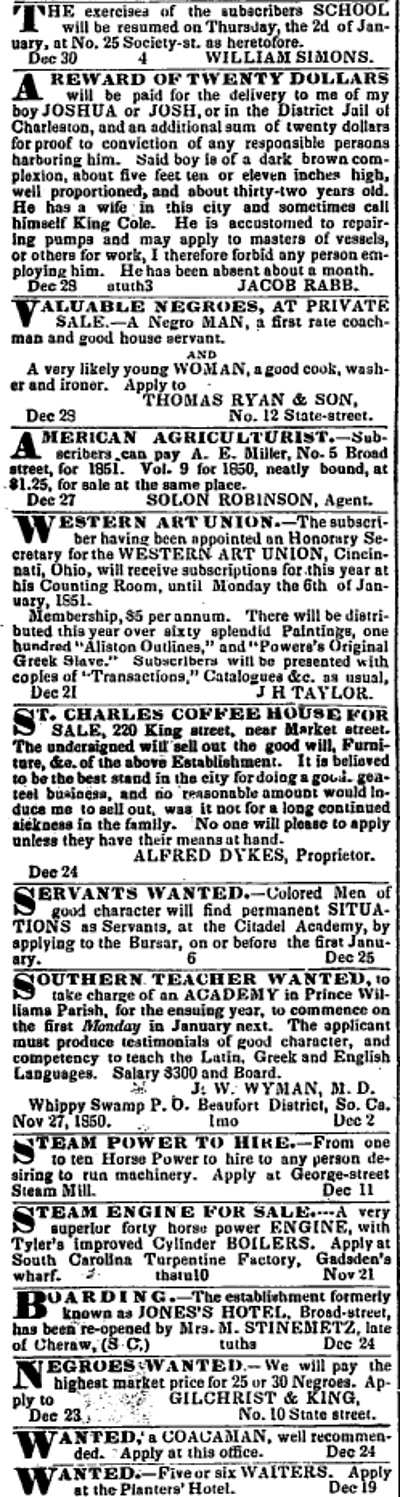

Such juxtapositions brought the living body into deliberate proximity with sculptural representation, activating sculpture’s special capacity to imitate real human presence, by approximating limbs, anatomy, and posture; and by standing and displacing space just as a living body does. Indeed, the practice of putting humans on exhibit is the specter behind satirical responses to The Greek Slave at the Great Exhibition—for example, in Punch’s comparison of “dead stone” with “living ebony.” Nor was this an isolated case. Just as The Greek Slave traveled from venue to venue, so did human exhibitions. In the 1850s, when The Greek Slave went on view in the Egyptian Hall as part of the Dudley collection, a variety of entertainments were conducted alongside, including dioramas “illustrated” with living individuals. One reviewer described the “Syro-Lebanon Company” of men and women brought in to enliven a Holy Land diorama: “With the well-defined art of the painter[,] nature has been judiciously blended.”[21] Moral ambivalence was part and parcel of the reception of The Greek Slave, as it was part of the wider culture. The satires in Punch and other periodicals were effective precisely because of the normality of these juxtapositions—it was normal that The Greek Slave could be displayed alongside “African children” who were “the offspring of slave parents”;[22] or that newspaper announcements of the sale of a Greek Slave statue could appear alongside announcements of the sale of human slaves (fig. 11),[23] as well as incidentally adjacent to advertisements for antislavery literature.[24]

All of this brings into focus the question of how people were looking at sculpture, and how that looking was mediated. The variety of display conditions highlighted in the interactive suggests, in turn, a variety of viewing experiences. The kind of contemplative looking we now associate with the viewing of art was not yet regularized, and did not become a dominant part of The Greek Slave’s public presentation until later in the century. From the 1840s into the early 1860s, while most actively on the move, the various versions of the statue were only occasionally placed into quiet isolation. Viewing was busy and eventful, and in many cases directed towards entertainment and audience engagement or structured around a point of interaction—such as the opening and closing of a curtain to expose and conceal the statue, the cranking of a lever to rotate the pedestal as viewers approached, the handing out of poems and notes to accompany viewings, or the side-by-side presentation of statues and living tableaux. These varieties of dynamic engagement emphasize the importance of the statue’s full, human-size presence in conditioning viewers’ responses. The timeline provides a useful reminder that the viewing of sculpture in the nineteenth century was much more dynamic and varied than it is now. The absorption of The Greek Slave into the art galleries of today was a gradual process, which began once the frenzy of touring was over and the statue was no longer novel.

Ownership and Sales

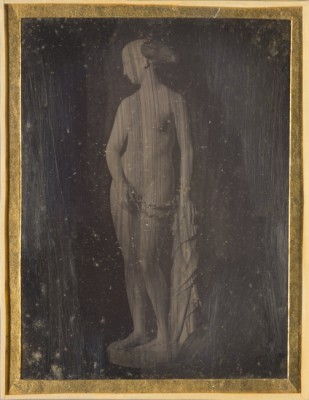

The diversity of The Greek Slave’s exhibition venues was mirrored by the diversity of the various versions’ owners. As the documents presented in “Mapping The Greek Slave” highlight, Powers made the statues (except the last) to order for specific clients. These clients were all male, wealthy, prominent members of their society. However, the statues did not always go to the client as planned, or go there immediately. First, they were sent on exhibition (with the exception of the fifth, completed in 1850, which was permanently sited near Florence in the villa of Anatole Demidoff—see Helen Cooper’s article in this special issue). Powers sent his second and third versions (completed in 1846 and 1847) on tour in North America after they were released unexpectedly by their prospective owners (see Tanya Pohrt’s article in this special issue). In 1846, Lord Ward released the sculpture Powers had made for him so that it could be sent on an exhibition tour (he later became owner of the fourth version, completed in 1847, which Karen Lemmey discusses in her article “Discovering the Lost Greek Slave in a Daguerreotype”).[25] In 1849, the Irish patron Sir Charles Henry Coote asked to be “relieved from his engagement,” Powers explained, “on account of the famine in Ireland.”[26] Powers was able to use these failed sales to his advantage, as the touring shows garnered enormous publicity. However, the absence of an initial, secure owner resulted in an itinerant and erratic sales history, making the trajectories of these two statues particularly remarkable.

When the flurry of touring was over, both statues ended up in the possession of art unions. These membership organizations were a phenomenon of the nineteenth century in both America and Europe.[27] Their business model was to collect subscription fees to fund the purchase of works of contemporary art, which were then distributed as lottery prizes to subscribers. The greater the membership, the greater the funds available. So successful were the art unions that they were able to buy not only prints and statuettes, but also major works of art. In 1849, the Western Art Union purchased the second version of The Greek Slave from James Robb in New Orleans for $3,500 and brought it to Cincinnati for exhibition.[28] In 1851, it was offered as the union’s first lottery prize and won by James D’Arcy, also of New Orleans and, curiously, Robb’s brother-in-law.[29] Prompted by the successful publicity generated by this venture, the Cosmopolitan Art Association followed suit. In 1854, it laid out $5,000 for the third version of the statue, which had been touring America since 1847, and exhibited it at its showroom in Sandusky, Ohio. The statue was offered as a prize in 1855. The winner, Kate Gillespie, sold the statue at auction in New York in 1857, where the Cosmopolitan Art Association repurchased it for $6,000. It was subsequently displayed in the association’s newly acquired Düsseldorf Gallery, and in 1858 was again offered as a prize (fig. 12).[30]

The lottery winners sold on their statues quickly. D’Arcy sold his to William Wilson Corcoran (1798–1888), the Washington banker, for $3,500 in 1851;[31] Miss A. E. Coleman, the final winner of the third version, to Alexander Turney Stewart (1803–76), the department store millionaire, for $6,000 in 1859.[32] Corcoran and Stewart were among the wealthiest patrons of their time, and both intended their statues to grace the private art galleries they were building as part of their sumptuous residences. Thus far, the two statues shared a remarkably similar path: moving from a popular sphere of public exhibitions and entertainments to the vicissitudes of a lottery that brought a costly object into the purview of ordinary, middle-class individuals, and finally arriving in elite private art collections. Despite haphazard beginnings, the journeys of the two statues appear to end predictably, almost inevitably, in the familiar story of gilded-age collecting.

But Corcoran and Stewart were not two of a kind. They occupied polar political positions, making the fates of their statues all the more fascinating. Corcoran was a Southern sympathizer and an occasional slave owner; clearly The Greek Slave was, for him, not about abolitionist sympathy.[33] Having bought his statue well before the Civil War, he placed it in a specially constructed niche in his residence. He had his daughter married in front of it in 1859 (incidentally, the same year Stewart bought his Greek Slave).[34] As his collection continued to expand, he commissioned the architect James Renwick to design a purpose-built gallery, but in the lead-up to the Civil War, things went awry. Corcoran’s Southern loyalties provoked resentment, and he moved to Europe, leaving his home in the hands of the French consul, Charles-François-Frédéric, marquis de Montholon. In his absence, the partially completed gallery was seized and given over to Montgomery Meigs, the quartermaster general of the Union army, and used by his staff as a supply store.[35] The marquis de Montholon continued to live in Corcoran’s home, and in 1866 he threw a lavish ball to celebrate the end of the war. The picture gallery was converted into a ballroom; at one end “a deep niche was draped with the flags of France and the United States, and there, half enshrined among flowers, stood Powers’s Greek Slave.”[36] It seems the statue’s potential meanings could shift even in Corcoran’s home, and regardless of its owner’s particular politics. Upon Corcoran’s permanent return in 1867, he had to rebuild his position, and his art collection was the key means by which he did so. In 1869, he gave his gallery to the nation, and it opened to the public five years later (fig. 13).[37]

In contrast, Stewart was a committed unionist. Letters and reports in the press through the 1860s track his views, donations, and other forms of support of the Union.[38] His dry-goods business thrived during the Civil War, thanks to major contracts for supplies to the Union army (some of which, we might speculate, ended up in the supply store housed in Corcoran’s gallery).[39] In 1869, Stewart’s name was sent to the senate by the president, Ulysses S. Grant, for confirmation as secretary to the Treasury. The appointment was denied because his import business disqualified him, but Stewart remained close to Grant. While Corcoran’s Greek Slave became secured as a museum object soon after the Civil War, Stewart’s continued with an uncertain future until 1926, when it was finally gifted to the Newark Museum. In the intervening years, Stewart’s Greek Slave became the most persistently newsworthy of the six marble versions by Powers. The prices paid for the statue were assiduously tracked by the press, particularly, as we shall see, when its stock began to fall. The trajectory of its course through the second half of the century offers some revealing insights into its changing fortunes, and those of marble statuary more generally. Although The Greek Slave never fell into obscurity as other sculpture of the period did, it nevertheless experienced a similar decline in value.

Having acquired The Greek Slave in 1859, Stewart waited another ten years—including the years of the Civil War—before building the private gallery in which it would be displayed. Construction of Stewart’s “marble palace” on Fifth Avenue, at a reputed cost of $2 million, was underway by 1867.[40] Upon its completion, Stewart gained a reputation as a major collector.[41] In the 1870s, his gallery became the subject of illustrated news reports, in which the sculptures—known as the “Stewart statues”—were marked out as a key attraction (fig. 14). The Greek Slave kept company with other works by American sculptors, including Powers’s Eve Tempted and Eve Disconsolate (1849 and 1871, both marble, present locations unknown)[42] and several works by Randolph Rogers. After Stewart’s death in 1876, his widow, Cornelia Stewart, continued to make acquisitions, including Harriet Goodhue Hosmer’s monumental Zenobia in Chains (1859, marble, The Huntington, San Marino) for a reported $2,750[43]—perhaps significant as a further sculptural meditation on female enslavement.

The growth of the Stewart collection attracted much attention, but when the death of Cornelia Stewart in 1886 occasioned a round of auctions, it became clear that the luster of the once-prized statues had faded. Newspapers reported an auction room filled to overflowing: paintings sold apace and made a total hammer price of over half a million dollars. Reporters speculated that the prices paid were in line with Stewart’s original outlay, and that the “fame” of his pictures had “endured or increased.”[44] The same could not be said of the statues. Collectively, they failed to meet their reserve. Newspaper headlines dramatized the collapse in The Greek Slave’s value: “Bidders Grow Silent and the ‘Greek Slave’ Is Not Sold,” the New York Times declared; “The Greek Slave Withdrawn,” said the Baltimore Sun.[45]

For the time being, the statues remained in Stewart’s marble palace. The executor of the estate was the judge Henry Hilton, and although he was soon embroiled in lawsuits claiming he had looted Stewart’s fortune, Hilton became the effective owner of the house and its contents. In 1890, he moved the statues out and leased the property to the Manhattan Club, a large Democratic membership organization. As the club undertook refurbishments, new details about the interiors emerged. Sensationally, a “hiding place” was discovered in the house, a private apartment that had been reserved for the use of President Grant.[46] Grant’s confirmation as president in 1869 (the year of his attempt to appoint Stewart to the Treasury) coincided with the completion of the house; perhaps the apartment was planned from the outset. According to reports, it had been luxuriously furnished and decorated with statues. The Greek Slave stood in a different room, but would have been encountered by any of Stewart’s guests. One cannot help but imagine that the statue may have held a special meaning for Stewart and Grant, perhaps standing as an abolitionist icon and oblique reference to the political roots of their friendship.

It is unclear what happened next to The Greek Slave. Hilton sent ten of the Stewart statues on loan to Denning’s department store on Broadway, the successor to Stewart’s stores, where they lingered for years among clothing and millinery like “baits for curious shoppers.”[47] Some later went on loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1899, Hilton’s death prompted a further sale. Paintings, statues, and “bric-a-brac” were auctioned over three days.[48] The Stewart statues remained unsold, passing into the estate. As legal rows and litigation beset the estate for more than a decade, The Greek Slave languished in a warehouse.[49] In 1913, a further sale of Hilton’s art collection was announced, bringing the statue back into the news. The collapse in value again made headlines in the New York Times: “Greek Slave Brings $1,250: A. T. Stewart Paid $11,000.”[50]

The sale also included the remaining Stewart statues. Among them was Hosmer’s Zenobia, which fell yet more dramatically in value, fetching just $200. The statues went to the same buyer, Joseph Raphael Delamar of New York and Long Island, a millionaire businessman and art collector who had made his fortune in the mining industry. The cycle of sales continued when Delamar died in 1918. The Greek Slave was sold to another businessman-collector, Franklin Murphy, whose son gave it to the Newark Museum in 1926, taking it permanently off the market. In contrast, Zenobia disappeared; it was presumed lost until 2008, when it dramatically reappeared at a Sotheby’s auction, from where it went to the Huntington in California for just under $400,000.[51] It is a telling story. Having come together in the Stewart mansion in 1878, The Greek Slave and Zenobia remained together, from owner to owner, for more than four decades. Whether their depiction of enslaved female figures contributed to their pairing is open to speculation. Nonetheless, their entwined histories exemplify the trajectory of nineteenth-century marble statuary, from the height of its prestige to its decline. It is also clear that The Greek Slave, unlike Zenobia, was able to transcend this shift—while its dollar value dropped, its celebrity held sway, securing its future at a time when estimation of its genre was at the lowest ebb. Its renown as a sculpture, and its iconic function as an ideological lightning rod for the divisive issue of slavery, combined to give it an exceptional status.

Curiously, Stewart’s political affiliations—which, after all, raise the possibility that The Greek Slave held symbolic meaning for him—have not entered into debates about the statue. The scholarship has focused on a bigger picture, which has conflated the multiple versions of The Greek Slave into a single object of interpretation. Perhaps exploring the statues’ many trajectories has appeared like so much provenance research, precisely the kind of historiography rejected by scholars seeking to reconnect The Greek Slave to its larger social, cultural, and political history. In a sense, this has meant taking sculpture out of a too-limited history of sculpture. I am not arguing for its return there, but instead for a more interconnected history. The multiplicity of The Greek Slave demands recognition of multiple, contextually sensitive meanings, and tracing ownership and sales histories is part of recovering that complexity. This special issue also seeks to contribute to a history that is productively connected to the present. The Greek Slave gives access to political and cultural histories tied to legacies of slavery that remain very much alive and relevant today. The statues also remain with us, and continue to confront viewers in all their troubling ambivalence. How we deal with these multiple, large, heavy, fragile, white objects in our museums is as important as how we deal with their history.

Using the Digital Interactive

This digital interactive is embedded here as an iframe; it can either be used within the essay, or accessed as an independent website by clicking the header “Mapping The Greek Slave.” The interactive is organized into three areas identified by tabs in the upper right: “Map,” “Timeline,” and “Research.” These areas allow us to slice through the same information in different ways. The first of these, the map, pinpoints all of the events associated with the six full-size marble versions of The Greek Slave and the two plaster models, from their place of production in Florence to the subsequent sites of their display in exhibitions, homes, and institutions. The interactive is based on a Google map, and allows zooming in and out by using a mouse or trackpad, double clicking, or using the “+” and “-” arrows within the map interface. The image bar at the bottom of the page displays all of the entries associated with the numbered pins in the current view of the map. If the user zooms in, only those entries that are pinned on the visible area of the map will be displayed on the image bar (figs. 15, 16).

Some locations are densely pinned—for example, Florence, since all the statues and the plasters were made in the same location. There, the pins are overlaid and can be hard to separate. The image bar at the bottom, however, shows what is layered together on the map. Clicking on a pin brings up a quick-view image of the associated entry. Clicking on that image opens the full-page entry. To return to the previous page, it is necessary to use the backspace or delete key on a keyboard.

Second, the timeline is organized in a strict chronology: events related to all the versions of The Greek Slave are shown in order, reflecting the ongoing display of multiple statues in different places at different times. The timeline is navigated by scrolling horizontally using a trackpad or the bar at the bottom of the page (fig. 17).

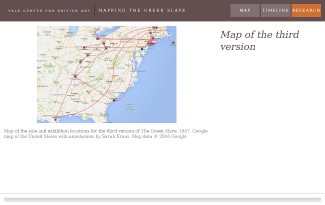

Third, “Research” provides the option of following each statue’s story in turn. The main landing page displays all of the entries associated with each version of The Greek Slave (fig. 18). The trajectory of each statue is summarized on a map, which appears as the final entry for each version (fig. 19).

Clicking on any image on the Research page opens the full-page entry, containing further information, related documents, and images (fig. 20). Clicking on the large image makes it full screen.

As far as possible, pertinent images—of the statues (in situ, when an image is available), the exhibition venues, the owners and their residences—have been included. Newspaper and magazine reports are shown when they substantiate an event, such as an exhibition or a sale; or if they contain specific information, such as a price or the name of a buyer. Clicking anywhere on an image enlarges it. On smaller screens, some texts may be difficult to read. To increase the size of the image, readers should use their browser’s zoom functionality. Images can also be downloaded and viewed at a larger scale. Since this resource is intended first and foremost to establish an empirical basis for the statues’ multiple histories, the selection of documents and images has focused on those that yield basic information about a particular event. These documents and images have, of necessity, been extracted from meaningful settings in order to be presented here. In drawing this material together, we hope to provide paths into the richly layered contexts from which each individual source was drawn.

Digital Humanities Project Narrative

The present project would not have been possible without advances in the digital humanities, both in how research is undertaken and in how information is presented. Almost all of the research was conducted online rather than physically in the archive, taking advantage of digitized newspapers, journals, and other primary sources. While this essay has put some of the results of this research into context, the interactive itself is intended as a resource—a foundation from which further research can develop. It makes no claim to be complete, in particular as it was compiled primarily from English and American sources. But the aim has been to use digitized sources to provide as full and accurate a history of each of the six versions of The Greek Slave as possible.

The platform used for “Mapping The Greek Slave” was developed some years ago by Night Kitchen Interactive for the Yale Center for British Art. It has been used in conjunction with exhibitions there, including Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901 (2014), which presented The Greek Slave alongside John Bell’s statue The American Slave (1853, bronze patinated electrotype with silver and gold plating, The Armstrong Collection, National Trust, Cragside, Rothbury, Northumberland), and provided the starting point for the present project. The interactive, titled “Sculpture and Ceremonial: Monuments to Queen Victoria,” allowed one section of Sculpture Victorious to be explored in greater depth. “Mapping The Greek Slave” is therefore not based on a bespoke piece of software; nevertheless, it adequately presents the information in the ways that we wanted: across space (on a Google map), in a chronology (along a timeline), and with a rich presentation of images and primary documents used to compile the research. Each of these three categories is accessible via the buttons “Map,” “Timeline,” and “Research” at the top right of the interface. We were not able to find readily available, lightweight (easy-to-maintain) open-source software that could be adapted to present the information in more nuanced ways (for example, by enhancing the legibility of the six versions on the map). But platforms like this will only improve with trial and error, by assessing their capabilities against the kind of knowledge we want to represent, and by making the data as widely and freely available as possible. As the digital humanities continue to develop, it is becoming increasingly apparent that technical platforms need to adapt to research needs. Great strides are being made in that direction, not least the development of Research Space (with the help of Andrew W. Mellon funding), the image-viewing platform Mirador, and international agreements, such as the Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF), for standards in digital image presentation. The aim of these larger international efforts is to arrive at serviceable multipurpose platforms that can be shared and adapted, providing scholars with the basis of a flexible digital interface. Most importantly, these initiatives depend on linked open data and the willingness of institutions, as well as individuals, to share data. It will be some time before these resources become fully operational and standardized. In the meantime, the challenges that we faced in the present project have usefully highlighted the kinds of technical developments needed to fulfill the huge potential of the digital humanities.

My special thanks go to Sarah Kraus, senior administrative assistant, Department of Research, Yale Center for British Art, for her help in the development of this digital interactive, both in contributing to the research and in providing invaluable administrative support. Generous assistance was also provided by A. Robin Hoffman, assistant curator, Department of Exhibitions and Publications; and Michael Appleby, head of Information Technology.

[1] The present project has built on the chronology in Richard P. Wunder, Hiram Powers: Vermont Sculptor, 1805–1873, 2 vols. (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1991), 2:157–67.

[2] Our research as especially benefited from ProQuest, Internet Archive, and Google Books.

[3] Mrs. E. D. W. M’Kee, “Excerpta—No. III. Aesthetic Education, or Moral Uses of Art,” Christian Parlor Magazine, May 1, 1853, 167–68.

[4] Edward Everett, “American Sculptors in Italy,” in Powers’ Statue of the Greek Slave (Boston: Eastburn’s Press, 1848), 9, 11. These references appear in a book of various press articles about The Greek Slave, which includes an introduction that refers readers to Powers’s tour manager, Miner K. Kellogg.

[5] Grant was articulating a problem shared by many artists and critics at the time, and the academy was under pressure to improve its display facilities for sculpture for much of the nineteenth century. See, for instance, “The New Sculpture Gallery at the Royal Academy,” Illustrated London News, May 18, 1861, 58.

[6] John Grant to Hiram Powers, May 8, 1845, Hiram Powers Papers, box 4, folder 52, frame 60, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (henceforth AAA), http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/container/viewer/Grant-John-284381.

[7] Ibid., frame 62.

[8] John Grant to Powers, October 9, 1845, Hiram Powers Papers, box 4, folder 52, frame 82, AAA, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/container/viewer/Grant-John-284381.

[9] “Nymph by Mr. Theed,” Journal of the Belles Lettres, June 21, 1845, 403.

[10] “Industrial Exhibition,” Times (London), April 29, 1851, 5.

[11] During the Graves display, “A Study from Nature,” a brief satirical column, was published in Punch, June 1845, 257. See also the entry for two versions of The Greek Slave in Martina Droth, Jason Edwards, and Michael Hatt, eds., Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 246, cat. nos. 80, 81.

[12] “America in Crystal,” Punch, May 24, 1851, 209.

[13] “Mr. Catlin and the Executive of the Great Exhibition,” Observer, August 31, 1851, 4.

[14] The Catlin collection is now at the Smithsonian. For further discussion, see Norman K. Denzin, Indians on Display (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2013).

[15] “Fine Arts,” Athenaeum, July 5, 1851, 722.

[16] “The Great Exhibition. Odd Incident,” Observer, August 25, 1851, 4.

[17] For instance, “The Gossip of Paris,” New York Daily Times, September 27, 1855, 2; “The Gossip of Paris,” New York Daily Times, October 10, 1855, 2.

[18] For the Hôtel d’Osmont, see Alexandre Dumas, ed., Paris et les Parisiens au XIXe siècle: moeurs, arts et monuments (Paris: Morizot, 1856), 196. For human displays at the Hôtel d’Osmont, see Diana Christina Sophia Snigurowicz, “Spectacles of Monstrosity and the Embodiment of Identity in France, 1829–1914” (PhD Diss., University of Chicago, 2000), 176–77, 228.

[19] For the placement of The Greek Slave alongside human displays, see “The Gossip of Paris,” September 27, 1855, 2. For more background, see Nadja Durbach, “Aztecs and Earthmen,” in Spectacle of Deformity: Freak Shows and Modern British Culture (Berkeley and London: University of California Press, 2010), 115–46.

[20] “The Gossip of Paris,” September 27, 1855, 2.

[21] “Miscellaneous,” Musical World, August 30, 1851, 558.

[22] “Our Weekly Gossip,” Athenaeum, September 8, 1855, 1032. A “private view of two little African children” took place at Drury Lane Theatre prior to their “public exhibition” at the Egyptian Hall.

[23] Charleston Mercury, December 31, 1850. An advertisement for the Western Art Union’s lottery for The Greek Slave nestles between others for “Valuable Negroes at Private Sale,” “A Reward of Twenty Dollars” for a missing slave, and “Servants Wanted.”

[24] Boston Liberator, August 10, 1849, 127. An advertisement for the Boston Horticultural Hall’s exhibition of Powers’s statues, including The Greek Slave, appears at the end of a column that begins with a list of abolitionist books “for sale at the antislavery office.”

[25] John Grant to Powers, February 18, 1849, Hiram Powers Papers, box 4, folder 53, frames 19–20, AAA, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/container/viewer/grant-john-339884.

[26] Ibid.

[27] See Joy Sperling, “‘Art Cheap and Good’: The Art Union in England and the United States, 1840–60,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 1, no. 1 (Spring 2002), accessed June 18, 2016, http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring02/qart-cheap-and-goodq-the-art-union-in-england-and-the-united-states-184060.

[28] Wunder, Hiram Powers, 2:161.

[29] “Letter from Cincinnati,” National Era, January 30, 1851, 19.

[30] The price is given in “New York City,” New York Daily Times, June 24, 1857, 8. See also Jane Aldrich Dowling Adams, “A Study of Art Unions in the United States of America in the Nineteenth Century” (PhD Diss., Carnegie-Mellon University, 1954), 34–35.

[31] Wunder, Hiram Powers, 2:161.

[32] Ibid., 2:164.

[33] Tom Lewis, Washington: A History of Our National City (New York: Basic Books, 2015), 160; Robert Thomas Sweet, “Selected Correspondence of the Banking Firm of Corcoran and Riggs, 1844–1858” (PhD Diss., Catholic University of America, 1982), 132, 143; Lauren Lessing, “Ties That Bind: Hiram Powers’s Greek Slave and Nineteenth‐Century Marriage,” American Art 24, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 62.

[34] “Marriage of a Millionaire’s Daughter,” Chicago Press and Tribune, April 18, 1859, 3.

[35] Charles J. Robertson, American Louvre: A History of the Renwick Gallery Building (Washington, DC: Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2015), 39–50.

[36] “Washington Letter,” Saturday Evening Post, February 24, 1866, 6.

[37] See Alan Wallach, “William Corcoran’s Failed National Gallery,” in Exhibiting Contradiction: Essays on the Art Museum in the United States (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998), 22–37.

[38] For instance, a $10,000 check to alleviate the suffering of British operatives, “Local Intelligence: American Aid for English Operatives,” New York Times, December 6, 1862, 3; and a reported million-dollar loan to the government, which he wrote about to the press, “Letter from Mr. A. T. Stewart,” Louisville Daily Journal, May 15, 1861, 3.

[39] “History of a Dry Goods Prince. How A. T. Stewart Made His $20,000,000,” Chicago Press and Tribune, August 29, 1860, 3.

[40] “A. T. Stewart’s New Mansion,” Cincinnati Daily Enquirer, April 12, 1867, 4.

[41] “A. T. Stewart’s Purposes,” New York Observer and Chronicle, March 25, 1869, 94.

[42] April Kingsley, “Hiram Powers’ Paradise Lost,” in Hiram Powers’ Paradise Lost, exh. cat. (Yonkers, NY: Hudson River Museum, 1985), 17–19.

[43] “Mrs. Stewart Buys the Zenobia,” Baltimore Sun, June 15, 1878, 6.

[44] “The Stewart Picture Sale,” New York Times, March 27, 1887, 8.

[45] “The Stewart Statues: Bidders Grow Silent and the ‘Greek Slave’ Is Not Sold,” New York Times, April 1, 1887, 5; “The Greek Slave Withdrawn,” Baltimore Sun, April 2, 1887, 5.

[46] “Where Gen. Grant Took His Rest: Discovery of an Apartment in the Stewart Mansion,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 20, 1890, 2; “Grant’s Hiding Place: It Was an Elegantly Furnished Room in the Stewart Mansion,” Austin Statesman, 12 March, 1890, 8.

[47] “Topics in New York,” Baltimore Sun, October 25, 1892, 2.

[48] “Close of the Hilton Sale,” New York Tribune, February 17, 1900, 7.

[49] “Greek Slave that Used to Shock Us Now Seems Harmless,” New York Times, November 9, 1913, 12.

[50] “Greek Slave Brings $1,250: A. T. Stewart Paid $11,000 for the Original Work of Sculpture,” New York Times, November 13, 1913, 6.

[51] The statue was lot 59 in Sotheby’s sale no. LO7232, London, November 13, 2007. “Auction Results: 19th and 20th Century European Sculpture,” Sotheby’s, accessed June 18, 2016, http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2007/19th-20th-century-european-sculpture-l07232/lot.59.html. See also the entry for Zenobia in Chains in Droth, Edwards, and Hatt, eds., Sculpture Victorious, 257, cat. no. 85.