Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel

Reviewed by Caterina Y. PierreCaterina Y. Pierre, Ph.D.

Professor, City University of New York, Kingsborough Community College

Visiting Associate Professor, The Pratt Institute

Email the author: caterina.pierre[at]kbcc.cuny.edu, cpierre[at]pratt.edu

Citation: Caterina Y. Pierre, exhibition review of Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 21, no. 1 (Spring 2022), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2022.21.1.19.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel

Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

September 26, 2021–January 9, 2022

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

February 24–July 31, 2022

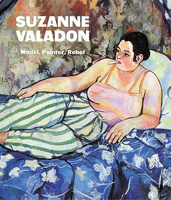

Catalogue:

Nancy Ireson, ed.,

Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel.

Philadelphia and London: Barnes Foundation, in association with Paul Holberton Publishing, 2021.

160 pp.; 100 color illus.; chronology; appendices; bibliography; notes; references; exhibition checklist.

$50 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978–1–913645–13–7

While viewing the exhibition Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel this past fall at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, I had a strong and distinct flashback that returned me to Montmartre in 2018. I remembered standing in Valadon’s reconstructed studio at the Musée de Montmartre at 12, rue Cortot, unmasked and unencumbered by the stresses of our current era. Marie-Clémentine Valadon (1865–1938), christened “Suzanna” by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, lived and worked there with her son, Maurice Utrillo (1883–1955) and her second husband, André Utter (1886–1948). She rechristened herself “Suzanne” in 1892, and, as they say, a star was born. While the Musée de Montmartre is not a “Valadon Museum” per se, one does have a sense of her accomplishments and spirit when standing in her light and airy studio, bright even on a cloudy morning (fig. 1). I remember reproductions of her drawings that were scattered around her desk, and a few paintings that graced easels around the studio. Suddenly, I was back at the Barnes, my mind awakened by some loud, chatty patron. Perturbed that I had been so quickly returned from Paris to Philadelphia, I nonetheless proceeded to view the exhibition at hand, finding a few works that I had seen before at museums in Paris and Geneva, and many others that I had never seen before in person.

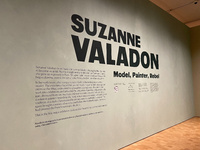

Like many art historians who have taught some version of “History of Women in Art,” and have included Valadon’s work as part of their content, I was quite familiar with the biography of the artist and less familiar with being in the presence of the physical works. There have been scant opportunities to see Valadon’s unique drawings, paintings, and prints in the United States. Art lovers may have caught some of them at the few museums that hold her works, if one was lucky enough to catch them on the walls, or at the two gallery exhibitions where her work was featured in 1958 (at the Hammer Galleries, New York) and 2003 (Frost & Reed, New York), if one was lucky enough to be in New York, and alive, in those years. But Valadon is known in North America, nonetheless: her art has been included in many general texts about women artists in history, notably in Whitney Chadwick’s Women, Art, and Society, now in its sixth edition and commonly used as the de facto undergraduate textbook for “women in art” courses.[1] It was therefore unsurprising to learn at the start of the exhibition that Model, Painter, Rebel at the Barnes was the first major retrospective of Valadon’s works in North America (fig. 2), but surprising to learn that its only venue in North America would be at the Barnes. (The show traveled to the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen and opened on February 24, 2022. It is also Valadon’’s first exhibition in Scandinavia.) Nevertheless, the Barnes Foundation’s exhibition was a rare opportunity for people who were able to travel to Philadelphia during the Delta and Omicron surges to see Valadon’s art in its full glory.

The exhibition was organized into six distinct sections entitled “Maria the Model,” “Suzanne Valadon, The Artist,” “Intimate Circles,” “Naked Ambition,” “Redefining a Genre,” and “Faithful to Figuration.” The first section, “Maria the Model,” presents Valadon in her first serious profession as an artist’s model (fig. 3). Some of the major works for which she is known to have posed did not travel to the exhibition, such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Dance at Bougival (1883, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) and the similar Dance in the City (1883, Musée d’Orsay, Paris); they were represented only in reproduction in the exhibition and in the catalogue. However, visitors were presented with the large and oft-copied painting by Gustav Wertheimer entitled The Kiss of the Siren (fig. 4), as well as works for which Valadon posed by Jean Eugène Clary, Vojtech Hynais, Santiago Rusiñol, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. From this selection, the viewer can see the range of poses and expressions of which Valadon was capable, and it becomes clear why so many artists wanted to work with her. It also becomes clear that she was like a chameleon, or a nineteenth-century Cindy Sherman: one can tell it is her in the image, though she appears a little different in each one, sometimes as an allegory or a siren, sometimes as a dancer, sometimes as herself. As noted by Martha Lucy in her catalogue essay on Valadon’s work as a model, in the art of many of the painters for whom she posed, “she would have seen different parts of herself—a limb here, a chin there—distributed across multiple bodies” (26).

Though she had no formal artistic training, which was hard to come by anyway if one was a woman of little means in the 1880s, she began to draw at the age of nine and, later, some of the artists for whom she posed recognized her talent. In the second section of the exhibition, “Suzanne Valadon, The Artist,” viewers were presented with drawings from a slightly later period (the 1890s and beyond) that give evidence for the talent that her artist-friends recognized in her work (fig. 5). Her charcoal drawing of her then twelve-year old son entitled Maurice Utrillo on a Couch shows her careful and assured hand (fig. 6). Beautifully composed and finely shaded, it is a work that can stand strongly next to any work by any draftsperson of the 1890s. A Nude Girl Reclining on a Couch, a black crayon drawing on yellow tracing paper, was no less skilled (fig. 7). Valadon’s signature cloisonné, or partitioned, outlining is, in both works, already quite evident. She met Edgar Degas, a man frequently generous to women with talent, in 1894, and he introduced her to printmaking; he became one of her first collectors. Some of his influence is evident in her drawings, pastels, and prints of bathers, such as a drypoint included in the exhibition entitled Catherine and Young Nude Boy (1910, Museum of Modern Art, New York). In the same year, Albert Bartholomé recommended her for inclusion at the exhibition of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where she was the first self-taught woman artist to exhibit there (6).

Valadon focused on her artistic career in earnest after 1909, when she was awaiting her divorce from her first husband Paul Mousis and was beginning a relationship with her son’s friend, André Utter, a man twenty-one years her junior. “Intimate Circles” focused on a productive and rich period, which began once she settled in Montmartre (fig. 8). She moved in 1911, with Utrillo, Utter, and her mother Catherine, into the former studio of the painter Émile Bernard at 12, rue Cortot, where she remained until 1925. It was the location where I had been transported in my mind during the exhibition, and it was the oil on canvas Landscape in Montmartre (Garden in the Rue Cortot) (fig. 9), shown here, that had transported me directly there. But it is in her Family Portrait (fig. 10), painted soon after their move into 12, rue Cortot, where one sees the real strength that Valadon possessed. In this one canvas, she was able to capture the serene pride of Utter, the sullen depression of Utrillo, the brooding reproach of Catherine, and her own composed apprehension about the situation she had created by leaving the financial stability of her marriage to Mousis and bringing this problematic group together under one roof.

Her turn to oil painting was directly related to the fact that she was now going to be the main breadwinner for her household (12). On the evidence of Family Portrait, she would have won any prix for têtes d’expressions. The painting Marie Coca and Her Daughter Gilberte (fig. 11) equally treats each figure with their own sense of self. Madame Coca drifts into a quiet daydream, as Gilberte seems to already be assured of herself as she stares directly at the painter, and by extension, the viewer. A nod to Degas appears on the wall in the form of a small painting of ballerinas on stage, just below Madame Coca’s eye level. The painting is tight, clean, and takes on the overhead and off-kilter angles and points of view for which Paul Cézanne is usually credited. The faraway glance of the mother and the wide-eyed gaze of the child prefigure the work of Alice Neel (1900–87), another artist who preferred figuration over the abstract tendencies of her own era.

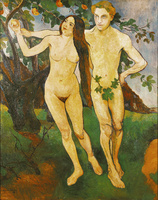

“Naked Ambition” focuses on Valadon’s nudes (fig. 12). Rarely in art history has the model had the chance to turn the tables and make someone else pose nude for them; in the catalogue that accompanied the exhibition, Martha Lucy points out that Valadon had the rare experience of having “occupied the position of both subject and object—painter and painted—in such a deeply engaged way” (20). The masterpieces in this section include the large-scale Adam and Eve (fig. 13) for which she and Utter posed, and Joy of Life (fig. 14). Two things struck me here as odd. Firstly, no mention was made of Henri Matisse’s famous Joy of Life from 1904–05, despite the facts that the painting shares the same title and resides in the Barnes Foundation. The two paintings do not look in any way alike, but the subject matter, nudes in a landscape, which was ubiquitous at the time in France, was worth some discussion. Secondly, how is it that this work by Valadon resides in New York, and I could not recall ever coming across it? The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired it in 1967 and does not seem to have exhibited it very frequently. The last time it was in an exhibition, according to the Metropolitan’s website, was twenty-six years ago in the Valadon exhibition at the Fondation Pierre Gianadda in Martigny. The Metropolitan also holds six other works by Valadon including two additional paintings and four drawings. One of those, the oil on canvas painting Reclining Nude (fig. 15) also on view at the Barnes, is a masterwork of form and color. The nude’s body is a modulation of pinks, yellows, and blues that give the flesh a semblance of life. Visitors in Philadelphia were lucky to see it, as objects from the Robert Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan rarely travel. This artwork had no exhibition history listed at all and has possibly never left the Lehman Collection for a traveling show.

The fifth section, “Redefining a Genre,” contained works from the 1920s, and it is only here that one senses Valadon was moving in a direction different from that of her contemporaries (fig. 16). Arguably her most famous painting, The Blue Room (fig. 17) was displayed here, on a wall by itself, which it deserved. Few artists can transition in one canvas from the tightly organized stripes on the model’s pants to the loose mix of colors in the background. (What is represented here in this background? Is it wallpaper? A curtain? A dream?) In this work, Valadon taps into a sort of feminist righteousness, a revolt on behalf of centuries of reclining female nudes, evidenced by the fact that she leaves her model in The Blue Room dressed, smoking a cigarette, with books on her bed at the ready. (A man once told me that I seemed to rather have books on my bed than a man; I failed to see his point.) Her series of images of a black model, as in Seated Woman Holding an Apple (fig. 18) and Black Venus (fig. 19), bring the image of a woman of color into the forefront. In many of Valadon’s paintings of female nudes, the models react, gaze back at the viewer, and move in ways that defy the idealization so typical in traditional nudes.

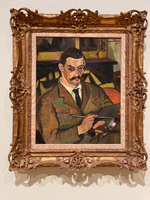

The final section, “Faithful to Figuration,” brings viewers to the end of Valadon’s life and career (fig. 20). According to the wall text, Valadon refused to exhibit with the Société des Femmes Artistes Modernes, whose shows only included works by women. Ireson suggests that she only did so in 1933 because she needed the exposure and the possible income that an exhibition can bring (15). In 1932, six years before her death, Mauricia Coquiot, the former circus performer and later wife of the art critic Gustave Coquiot, organized her most important lifetime retrospective at Galerie Georges Petit in Paris. Valadon’s portrait of Madame Coquiot (fig. 21) combines the motifs that by this time she had honed well: still life, portraiture, and a loose, painterly background that emulates a curtain of shimmering material but that also shows that Valadon was conscious of the more abstract paintings of her contemporaries. Her portrait of her son Utrillo from 1921 (fig. 22) is an excellent example of Valadon’s ability to synthesize the works of Cézanne, Gauguin, and even Pierre Matisse, and still produce something, in the end, that is uniquely her own.

The catalogue for the exhibition contains the most up-to-date scholarship on Valadon and her works. Nancy Ireson’s “Locating Suzanne Valadon” sets the biographical context for the following essays. “Painting from Both Sides of the Easel: Suzanne Valadon and the Female Nude,” by Martha Lucy, maintains, correctly, that Valadon’s nudes “defied long-held conventions for presenting the ideal female body as flawless, sensual, and passive” (18). Lucy takes up the discussion of Valadon’s early modeling career, which began around 1880 and lasted for a decade (20), detailing some of the works for which she posed. She then moves on to discuss Valadon’s nudes, making a very thought-provoking point that since Valadon was not professionally trained, she was also untarnished by the rules of propriety governing what subject matters women should and should not paint (26). The online conversation on Valadon’s Black Venus between Adrienne L. Childs, Nancy Ireson, Lauren Jimerson, Denise Murrell, and Ebonie Pollock, was transcribed and edited by Corrinne Chong for the catalogue. Here we learn, from Ebonie Pollock’s research for her BA thesis, of Valadon’s hiring of a black model for a series of five paintings that she created in 1919, the same year of W.E.B. Du Bois’s first Pan-African Congress that demanded equality for people of African descent. While it would be nice to learn the proper name of Valadon’s model, it is, to me, less important than the fact that the artist took the black model (imagine here, for example, Edouard’s Manet’s Laure from his painting Olympia of 1863) and moved her into the main position of focus. Lisa Brice’s essay analyzes The Blue Room from the context of the modern image of reclining nudes, some accompanied by black models, and comparing Valadon’s work with that of Manet, Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876–1907), Alice Neel, Florine Stettheimer (1871–1944), and Félix Vallotton (1865–1925), as well as with works by contemporary artists. These essays are followed by brief introductions to each section of the exhibition, and selected images. A chronology (compiled by Marianne Le Morvan), a selection of primary sources, a list of selected exhibitions, a bibliography, and an exhibition checklist round out the publication. Except for a bizarre problem in the type spacing of some of the essays, which makes these contributions hard to read physically, the content of the catalogue is a significant contribution to art history, and it contains many excellent image reproductions.

The exhibition as presented at the Barnes Foundation did not contain artworks by other artists, except in the first gallery where Valadon is shown as the model. Much is made of Valadon’s admiration for Paul Gauguin in the catalogue (especially in the discussion on the Black Venus series), but his name is not evoked in the exhibition, as if just the mere mention of his name would conjure “woke” mobs and Death Eaters. However, if one is familiar with his work, one could not miss his influence on Valadon, particularly in the paintings of nudes in landscapes and the cloisonné development of the forms. One could, if they wished, see a fair number of works by Maurice Utrillo, as well as by other artists whom Valadon knew, most notably Renoir, in the frustrating yet glorious jumble that is the Barnes collection, the flea market display of my dreams. In looking at Utrillo’s bright and crisp street scenes outside of the Valadon exhibition but within the main collection (spread out over various rooms), I was touched most by his signature, “Maurice Utrillo V.”–his mother’s influence was evident there, floating at the end of his name like a prayer (see for example his Chartres, Church of Saint-Atignan, ca. 1914, fig. 23). She gave her son more than a name to legitimize him; she imparted to him her lifelong devotion to art, which certainly gave him purpose and surely stabilized him during his years struggling with alcoholism and schizophrenia. While a stronger connection to the artistic milieu of her own times may have strengthened some of the wall text within the exhibition, it was refreshing to see an exhibition focused on a woman artist that was uncluttered by discourteous justifications and excessive references to similar works by male artists (a problem from which the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2021 exhibition Alice Neel: People Come First clearly suffered).

Adolphe Basler, in his preface to the 1928 exhibition catalogue that accompanied Valadon’s solo exhibition at the Galerie des Archers in Lyon, noted that “misfortune hounded this forceful artist. In the shadows during her lifetime, she is only receiving long-overdue recognition. Devoting to her art an obsessive passion, this fervent and fiery soul never burdened herself with concerns of fame” (149). That may be true, as she seemed satisfied with what she had accomplished when she said, as quoted on a wall label at the end of the exhibition, “I found myself, I made myself, I said what I had to say.” Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel at the Barnes Foundation allowed Valadon to say what she had to say, even if it did take eighty-three years after her death for a museum in the United States to allow her to say it. Returning to my reverie at the beginning of the exhibition, after viewing the entire exhibition at the Barnes, I realized I saw more and learned more about Valadon at the Barnes than was possible in Montmartre. I am certain that I would find it difficult, after seeing this exhibition, to return to Montmartre—this time physically, and not in a daydream—without recalling Valadon’s significant impact on the history of painting, and on women’s contributions to that history.

Notes

[1] Whitney Chadwick, Women, Art, and Society, World of Art Series, 6th ed. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2020).