Modern Architecture in Kyoto

Reviewed by Matthew LarkingMatthew Larking, PhD

Adjunct lecturer

Kindai University, Japan

Email the author: matthew.larking[at]lac.kindai.ac.jp

Citation: Matthew Larking, exhibition review of Modern Architecture in Kyoto, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 21, no. 1 (Spring 2022), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2022.21.1.17.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Modern Architecture in Kyoto

Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art, Kyoto

September 25–December 26, 2021

Catalogue (in Japanese):

Ishida Junichirō and Maeda Naotake, eds.,

Modan kenchiku no Kyōto 100 (Modern Architecture in Kyoto 100).

Tokyo: Echelle-1 Co. Ltd, 2021.

320 pp.; color and b&w illus.; bibliography; maps; chronology; guidebook.

¥3000 (softcover)

ISBN: 978–4–904700–05–1

The historical transition from premodern to modern Kyoto is frequently posed dialectically. Historian Matthew Stavros, for example, concluded with a decidedly Hobbesian assessment in Kyoto: An Urban History of Japan’s Premodern Capital:

For all its cultural brilliance, premodern Kyoto was a dirty, dangerous, and perpetually unfinished place. Fires frequently wiped out large portions of the cityscape, and civil strife was common. The many famous temples and shrines so celebrated today were often poorly maintained, and the Kamo River was notoriously strewn with rubbish and rotting corpses.[1]

As Japan’s most significant epoch of rapid modernization and cultural contention, Japan’s Meiji period (1868–1912) was purportedly a nineteenth-century ideal of “civilization and enlightenment,” an “age of progress.”[2] Vicissitudes, national and local, brought Kyoto to the transformative cusp. Of paramount significance had been the opening of Japan to much wider international trade and cultural commerce following the arrival of the Perry Expedition in the Edo Bay in 1853. The centuries of relative isolation imposed upon the country by its authorities was gradually lifted. Locally, the “Kinmon no Hen” fire of 1864 laid waste to large swathes of Kyoto, decimating central districts and infrastructure and sending the city’s population into decline.[3] The latter was exacerbated when Emperor Kōmei (1831–67) died suddenly. His teenage heir was enthroned in 1867 and imperial rule was restored, putting an end to Japan’s rule by samurai governments since the Kamakura period (1192–1333). The Emperor Meiji (1852–1912) moved the seat of imperial power, supposedly temporarily, when he left Kyoto for Tokyo in 1868, carried by palanquin. The relocation became permanent from March 1869. What followed was more evacuation than migration. Those serving the imperial court, the surrounding daimyo and their entourages, and merchants reliant on their clienteles, abandoned Kyoto.[4]

The public and private sectors combined forces to modernize Kyoto in a Western manner from the later 1870s through the 1910s, seeing this as a cure for its ills. Technology and modern science offered the promises of progress in education and industrialization. The Oridono Textile Factory, for example, was operated by the Kyoto Prefectural Government and introduced Jacquard looms imported from France and Austria. Research into and promotion of chemical dyes and new ceramic techniques and glazes, especially from the work of the German chemist Gottfried Wagener (1831–92), followed from the Meiji government’s encouragement of introducing practices and techniques from abroad. Such first efforts often awaited later privatization to make them profitable. The nation’s first elementary school was opened in Kyoto, followed by schools for women. The Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting, the oldest public art school in Japan, opened in 1880, and the Dai San Koto Chugakko, an advanced secondary school founded in 1889, became the forerunner of today’s Kyoto University. Among the catalysts for future industry was the 1890 completion of the Lake Biwa Canal. Initial purposes included supplying power to local industry, watering farmland, fire prevention, and assisting in the facilitation of water transport between Kyoto and Osaka. The city’s street lamps and Japan’s first streetcar were the publicly relatable instantiations of electricity’s new potential.[5] Western-looking brick buildings became a symbol of the new age.[6]

Modern Architecture in Kyoto is comprised of an exhibition at the recently refurbished Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art as well as buildings selected from throughout the city. It is a historical survey of the kind of architecture tourists do not conventionally flock to the city to see. Rather, this exhibition hones in on the architectural heritage that emerged from the various surges of modernization that began in the late decades of the nineteenth century, including architectural sites from the Meiji, Taisho (1912–26), and early-mid Showa (1926–89) periods.

The exhibition’s catalogue contains essays and entries on individual objects, but it is also a guidebook to related architecture in Kyoto, complete with maps. The forty-page, supplementary “archive edition” included within the catalogue contains further details about exhibits featured in Modern Architecture in Kyoto, project data, a chronology, and a book guide for modern architecture in Kyoto, all in Japanese. An English Kindle version of Modern Architecture in Kyoto 100 has been planned though it does not yet appear to be available at the time of writing.

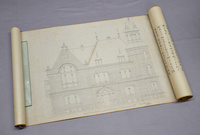

In the museum, Modern Architecture in Kyoto features original concept drawings and designs, a wealth of architectural models, period decorative furniture, photographic documentation, and films (figs. 1–4). Conceived from a viewpoint of achieving sustainable development goals in a post-Covid context, the exhibition adopted three vantages from which to consider the overall grouping of buildings under historical survey. The first was to reconsider Kyoto’s modern architecture against the postwar cycles of demolition and rebuilding that threatened the city’s historic interest. In recent decades, preservationist positions have come to vaunt the economic potential of maintaining a distinctive cityscape. The second followed from Japan’s National Registration of Tangible Cultural Properties, a system that endeavors to protect buildings over fifty years old and of historical importance. The third was to consider Kyoto as a living architectural museum with individual human and social context relationships: rather than merely buildings as historical markers, the exhibition attempts to shed further light on the architects and figures involved in the commissioning and construction, the changing roles of these architecture styles over time, and how these buildings became enmeshed in the everyday lives of particular individuals and the wider populace. Hence, while the exhibition venue is the ostensible first port of call and an architectural attraction itself, a catalogue/guidebook offers further opportunity to explore Kyoto architecture in its ongoing and occasionally repurposed roles. Guided walking tours were an additional feature of the exhibition program.

The forms and functions of the new architecture styles in the later nineteenth century were fundamentally different from their premodern counterparts. The Meirin Elementary School (presently the Kyoto Art Center) was established in 1869 as part of the citywide push to become the country’s education center. The construction of modern educational facilities also went in hand with comparatively recently introduced religious buildings, such as Clarke Memorial Hall (1894) on the campus of Christian-founded Doshisha University (figs. 5, 6). Originally this was the Theology Hall designed in a neo-Gothic style by German architect Richard Seel (1854–1922). Katayama Tokuma’s (1854–1917) Imperial Museum of Kyoto (1895), of which the pediment above the front entrance includes sculptures of the Asian gods Visvakarman and Gigei-Tennyo, deferred to French Baroque design (figs. 7, 8). Planned in three stories then reduced to one, the brick masonry structure housing the nation’s cultural treasures was down-sized following lessons learned from the Great Nobi Earthquake of 1891. The exterior of the Kyoto Branch, Bank of Japan (since 1988 repurposed as the annex of the Museum of Kyoto) was finished in 1906 in the English-style red brick wall with stripes aesthetic, a manner referred to as the “Tatsuno style” after the architect Tatsuno Kingo (1854–1919), who was its most famous exponent. The Shimadzu Corporation transferred its headquarters to Kyoto city’s central Kawaramachi-Nijo location in 1927. Designed by Arakawa Yoshio (1894–1957) with Takeda Goichi (1872–1938) as architectural advisor, its 2012 renovation transformed it into a restaurant and wedding hall.

Residential architecture of distinctive kinds developed in due course. Chochikukyo (1928–33) was Fujii Koji’s (1888–1938) final residential design, one ostensibly harmonizing modern Western and Japanese aesthetic sensibilities. An arguably less consonant though compartmentalized aesthetic informed the luxury villa known as Chorakukan (fig. 9). Built in 1909 by Sunrise cigarette’s “tobacco king,” Murai Kichibei (1864–1926), Chorakukan was designed by US architect James McDonald Gardiner (1857–1925). The evident grandeur meant it was at times used as a state guest house. The first floor had a Renaissance style reception room, followed by guest rooms of a Rococo bent, and a neoclassical dining room. The second floor featured an Islamic smoking room (later altered to Chinese adornment), and the third-floor Japanese rooms surrounded a central shoin (residential architecture) style reception room referring to Japan’s Momoyama period (1573–1615). Most of the imported architectural styles mentioned above materialized first in the political and commercial centers of Tokyo and Osaka. Kyoto’s modern architecture had gone up in their wakes and largely following their examples. Seen in retrospect, historicism and eclecticism are the overarching trends in this architecture. The diverse forms and amalgams, however, were also once rooted in later nineteenth- and early twentieth-century universalist concepts and contexts.[7]

The exhibition was organized under seven themes: Revitalization of the Ancient City in the Modern Era; Magnificent Classical Architecture; Bridging Japan and the West; Dreams of a Missionary Architect; Residences and the Modern Community; City Life and Modernity; and Kyoto as Ideal of Modernist Architecture. Japanese modernism is too often seen as merely derivative of the West. In fact, its origins were complex, though an important moment occurred in 1877, when the government brought in Englishman Josiah Conder (1852–1920) to establish architecture as a field of study at the Imperial College of Engineering, an institution that later became part of Tokyo Imperial University. Conder’s charge, in addition to erecting his own designs as examples and models to emulate, was to train a generation of fledgling Japanese architects. Many became the major figures of the subsequent generations. Itō Chūta (1867–1954), an architecture student of Tatsuno Kingo (1854–1919), the latter being among Conder’s first graduating students, was of crucial significance for Kyoto.[8]

The most conspicuous public, large-scale and symbolic revitalizations of Kyoto arrived with the double billing of the fourth National Industrial Exhibition and the construction of Heian Jingu Shrine (1895) as an example of revivalist Heian period (794–1185) architecture (fig. 10). An early local precedent for the national/international exposition forum had been established in 1871 and held annually in Kyoto until 1929 at the Nishi Honganji Temple with the aspiration “to take the lead in enlightening people to the world of knowledge and art.”[9] The fourth National Industrial Exposition, the first to be held outside Tokyo but also emulating the period’s international predilection for the World Fair model, was roughly coincident with celebrations proposed to commemorate the 1100th anniversary of the foundation of Kyoto. Heian Jingu was to be the modern shrine honoring the ancient capital’s founder, Emperor Kanmu (737–806). As such, this became modern Japan’s “first major historical reconstruction.”[10] Designed by Kigo Kiyoyoshi (1845–1907), a master carpenter and an Imperial Household Agency architect, and Itō Chūta, whose university graduation project had been a gothic cathedral, Itō initially attempted a reconstruction of the reception hall of the ancient palace in its entirety.[11] Owing to time and scale limitations, and also restrictions on forthcoming funds, only the central structures were constructed at a 5/8 scale.

Among other works by Itō addressed in the exhibition is his Main Building, Shinshu Shinto Life Insurance Company (presently Honganji Dendo-in) from 1911. After embarking on a Grand Tour through Asia and a number of Western countries between 1902 and 1905, Itō began integrating variant ethnic and cultural forms into his buildings. The domed roof of the three-storied tower and red brick walls of the Main Building, Shinshu Shinto Life Insurance Company, were of Western inspiration. A traditional Japanese bracket system atop the columns supported the dome. The newel posts of the railing around these columns are capped with onion forms, inspired by Islamic multifoil arches and stalactite decorations. Established by funding from Nishi Honganji Temple, this building was also understood as one of the ways in which modern conceptions of Buddhism might be invigorated.

“Magnificent Classical Architecture” addresses Western-style architecture in Kyoto from the later Meiji period, following after the stylistic directives provided by the examples of concurrently modernizing Tokyo and Osaka. The stylistic cues, while new in Japan, were frequently backward-looking regarding Western architecture. Part of this was because modernism in Japan, while forward-looking, also examined the Western developments that led to modernism, hence the Spanish, Renaissance, Tudor, and Baroque architectural directions. Such stylistic, formal, and spatial dimensions were set to work in a number of formats, including government offices, banks, and private residences. The Shimomura Shotaro Residence, known as Chudoken (“Chūdō” being a near homonym for “Tudor” in Japanese), was built in 1932 for the president of the Daimaru Department Store, which had been expanded and diversified from an Edo period (1603–1867) kimono shop business (fig. 11). Designed by Vories & Company, the structure emulated Tudor England revivalism owing to the impression made on Shimomura by the edifice of the Liberty Department Store he saw when visiting London in 1908. The low, pointed arch, seen from the building’s front, was seen as characteristically Tudor in style, though the construction of the residence was in reinforced concrete. Wooden columns were affixed to the external walls to give the impression of a more authentic wood-frame construction.

Among the most enduring and productive legacies of modernism in Japan have been the ongoing conflicts and apparent resolutions between Japanese and Western sensibilities. The exhibition’s third section, “Bridging Japan and the West,” touches on varied interpretations of the issue. Among these, the exhibition site, originally the Kyoto Enthronement Memorial Museum of Art that opened in 1933 and now known as the Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art, is a superlative example of an East/West composite (figs. 12, 13). The structure was originally built to commemorate the 1926 ascension of the Showa Emperor, and designed in a fusion of what the exhibition materials refer to as a Wrightian Japanese style (raito-shiki), referring to Frank Lloyd Wright’s (1867–1959) architectural influence in the country through the early decades of the twentieth century. Maeda Kenjirō’s (1892–1975) design followed from the competition brief for a site-specific, Japanese architecture. It also catered to the “Imperial crown” architectural style that was a nationalist period riposte to international modernism. The steel-frame construction was crowned with a copper roof and a tiled exterior, the upshot of which was to draw attention to longstanding Japanese aesthetic sensibilities. Other Japanese details included the chidori-hafu gable roof centered on the front facade, decorative metalwork, and the frog-leg struts. In 2017, the Kyoto-based Kyocera Corporation bought the naming rights of the museum for the next fifty years and funded the complex’s retro-contemporary refit. Architects Aoki Jun (b. 1956) and Nishizawa Tezzo (Tetsuo) (b. 1974) oversaw the refurbishment and additions, including the Higashiyama Cube construction with its display focus being contemporary art, fashion, and design, and the unearthing of the basement below the museum’s entrance to create a sunken “glass ribbon” façade (figs. 14, 15).

Another elaborate decorative amalgam of East and West arrived when the city commissioned Kyoto Imperial University’s Takeda Goichi (1872–1938) to be the architectural advisor for the Kyoto City Hall Main Building (the first stage of construction was completed in 1927, with the second stage finishing in 1931) (fig. 16). As a reinforced concrete building of seemingly Western-looking inspiration with symmetrical wings spreading either side from a central tower, the turrets on the tower’s crown follow the form of a calligraphy brush. Indian-style reliefs were inserted in between these and Japanese funa-hijiki brackets supported the balcony below. The interiors were furnished with Islamic ogee arches and the ceiling decorations featured Asian lotus and chrysanthemum motifs.

In the early Meiji period, the Catholic, Protestant, Anglican, and Russian Orthodox churches all established branches from which to conduct outreach activities in the city. Their buildings constitute the exhibition’s fourth section. Kyoto’s principal three missionary architects were Daniel Crosby Greene (1843–1913) (Chapel, The Doshisha, 1886), J.M. Gardiner (Chorakukan, mentioned above) from the Episcopal Church in America, and W. M. Vories (1880–1964) (the Daimaru Villa, mentioned above, and Restaurant Yaomasa, 1927, present day Tokasaikan) who entered Japan through the YMCA. He shortly after had his English-language teaching contract rescinded and so turned to establishing a Christian brotherhood and an architectural office in Kyoto’s neighboring Shiga prefecture, producing over 1,000 buildings in Japan and South Korea, of which a little over one hundred are still extant.

Doshisha University’s Imadegawa campus and its surroundings are a particularly important locus of Meiji-period missionary architecture. The university’s founder, Joseph Hardy Neesima (known in Japanese as Niijima Jō, 1843–90), returned from the United States in 1875 and set up an English school that in later days became Doshisha University. The Neesima Residence (1878) is a Westernized two-story colonial-style frame house, complete with veranda (fig. 17). Some of its details relate to Neesima’s experience living in the West (for example, the Western toilets and the heating system in the reception room), but the simple nature of the architecture and interiors reflect his missionary sensibilities. Many of the other religious buildings featured in the exhibition are inspired by Gothic architecture or feature a characteristic red brick masonry construction. Mission school architecture was also erected to instill a kind of vision of paradise-type appreciation in the beholding of such campuses.

Section five covers the architecture of some of the more exceptional cultural locations of modern city life such as the tea parlor (or salon de lé français), established and renovated with Romanesque, Gothic, and Colonial-style details by the Communist activist Tateno Shōichi (1907–95) from 1934, and the beloved Kyoto bakery, Shinshindo. The latter was established in 1913 (though the two-storied wood-frame structure was completed in 1930) by Tsuzuki Hitoshi (1883–1934). A devout Christian, he thought of the business as a place for serving God and the people of the city through bread. Tsuzuki was apparently the first Japanese to go to Paris to learn the techniques of bread-making.

Section six concerns the private residences of Meiji period artists (Konoshima Okoku House), scholars (Kitashirakawa Scholars Village and Dr. Komai’s Residence), and the generally wealthy (Murin-an), particularly as these figures relocated to the geographical outskirts of the city as the Meiji period was coming to a close and as the city’s population was recovering from its decline during the late Edo and early Meiji periods. An architectural exception in this section is the Horikawa Housing Complex, built on land that had been cleared during WWII as a central city firebreak for anticipated air raids.[12] Completed in sections between 1950 and 1953, the complex was intended by the Kyoto Prefecture Housing Association to address the lack of inner-city residences while providing fireproof housing and revitalizing the local shopping district.

The exhibition’s final portion is devoted to architecture from the later Taisho and early Showa periods, reaching forward to the early 1970s. Once again, the featured architecture styles take on distinctly different roles and functions that develop away from the pragmatic modernist considerations found in the exhibition’s originating Meiji period. Featured works include the rationalized residential architecture of the Former Motono Seigo House constructed in 1924, and the Kyoto Imperial University (present-day Kyoto University) Kwasan Observatory, completed in 1929. The postwar chronology for this section concerns the Japanese architectural world’s movements in tandem with, and in divergence from, international trends through to the 1970s. Latter-day foci include the Kyoto University Sports Gymnasium designed by Masuda Tomoya (1914–81) and constructed in 1972, and the Kyoto International Conference Hall, completed in 1966 and designed by Otani Sachio (b. 1924) (fig. 18). This last building was the venue in which the 1997 Kyoto Protocol framework for the prevention of global warming was endorsed. The structure’s most distinctive feature is the enormous external trapezoid forms in reinforced concrete that also infiltrate the building’s interior.

Kyoto has numerous contemporary structures by world-renowned Japanese architects. A few examples would include Andō Tadao’s (b. 1941) Times Building (first stage completion 1984, second stage completion 1991), Arata Isozaki’s (b. 1931) Kyoto Concert Hall that opened in 1995 as part of the commemorations of the 1200th anniversary of the foundation of Kyoto, and the opening in 2020 of Kuma Kengo’s (b. 1954) Ace Hotel adjoining the renovated Shin Puh Kan (Former Kyoto Central Telephone Office) restaurants and shopping center. But curtailing the architectural chronology of the exhibition in the 1970s promotes a demarcation in both history and reputation, and not one of period with which the exhibition began. Enthusiasm for Kyoto’s architecture, both locally and internationally, has focused overwhelmingly on premodern monuments, then skipping forward to those structures and architects of the later twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Intervening modernism, its meanings, products, and producers, remain wedged into a much more contested cultural field of uncertain identity and legacy, despite the fact that the works under consideration in the exhibition constitute the very infrastructure of the city in recent historical and contemporary life. The exhibition’s focus, then, on the comparatively lesser-known and seemingly less-loved architecture from the beginning of the Meiji period to the 1970s, is to be applauded. It resists the simplistic reductions of this work implicit in charges of reductionism and exoticism, and it redresses a great lacuna in architectural history, examining beautiful and overlooked buildings with nuanced attention.

Notes

[1] Matthew Stavros, Kyoto: An Urban History of Japan’s Premodern Capital (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2014), 184.

[2] Yoshida Mitsukuni, “Kyoto’s Role in the Modernization of Japan,” in Kikyū ga agatta: Kindai Kyōto no isseiki (A Balloon Ascended: Kyoto, the Last Century), exh. cat., trans. Mikiko Murata and Dianne Durston (Kyōto: Kyōto-fu Kyōto Bunka Hakubutuskan, 1988), iv.

[3] Alice Y. Tseng, Modern Kyoto: Building for Ceremony and Commemoration, 1868–1940 (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2018), 23.

[4] Tseng, Modern Kyoto, 1–2.

[5] Yoshida, “Kyoto’s Role in the Modernization of Japan,” iii–vii.

[6] Reynolds states that “brick construction was not popular with merchants and residents, who found them dark and damp.” Jonathon M. Reynolds, “Can Architecture be both Modern and ‘Japanese’?: The Expression of Japanese Cultural Identity through Architectural Practice from 1850 to the Present,” in Since Meiji: Perspectives on the Japanese Visual Arts, 1868–2000 (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2012), 317.

[7] For an engaging discussion of this complex topic, see Toshio Watanabe, “Japanese Imperial Architecture: From Thomas Roger Smith to Itō Chūta,” in Challenging Past and Present: The Metamorphosis of Nineteenth-Century Japanese Art (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006), 240–53.

[8] Reynolds, “Can Architecture be both Modern and ‘Japanese’?,” 317–18; Watanabe, “Japanese Imperial Architecture,” 240–53.

[9] Yoshida, “Kyoto’s Role in the Modernization of Japan,” v.

[10] Tseng, Modern Kyoto, 2.

[11] Reynolds, “Can Architecture be both Modern and ‘Japanese’?,” 321.

[12] Though not widely known, Kyoto was bombed on a small-scale five times in 1945, seemingly by accident. The first was in Umamachi on January 16, then Sakyo-ku on March 19, Uzumasa on April 16, Kita-ku on April 22, and Jyokyo-ku and Chukyo-ku on May 11. Kyōto kūshū o kiroku suru kai (Association for Recording the Kyoto Air Raids), ed., Kakusareteita kūshū: Kyōto kūshū no taiken to kiroku (Hidden Air Raids: Experience and Records of Kyoto’s Air Raids) (Kyōto: Chōbunsha, 1974), 9–10. Nakanishi Hirotsugu tallies forty-one dead for the Umamachi bombing, with fifty-six injured and over three hundred houses damaged. For the Uzumasa incident, his figures indicate two dead and forty-eight injured. Nakanishi Hirotsugu, Sensō no naka no Kyōto (Kyoto in the War) (Kyōto: Iwanami Shoten, 2009), 141–43. The other bombed areas reportedly suffered no casualties and relatively few injuries.