Ingres: L’Artiste et ses princes (Ingres: The Artist and His Princes)

Reviewed by Andrew Carrington SheltonAndrew Carrington Shelton

Professor

Department of History of Art, The Ohio State University

Email the author: shelton.85[at]osu.edu

Citation: Andrew Carrington Shelton, exhibition review of Ingres: L’Artiste et ses princes (Ingres: The Artist and His Princes), Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 2 (Autumn 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.2.21.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Ingres: L’Artiste et ses princes (Ingres: The Artist and His Princes)

Château de Chantilly, Chantilly

June 3–October 1, 2023

Catalogue:

Mathieu Deldicque and Nicole Garnier-Pelle, eds.

Ingres: L’Artiste et ses princes.

Paris: In Fine éditions d’art, 2023.

288 pp.; bibliography; chronology; notes; references.

€34 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978–2382031193

In the wake of the massive international exhibition of Jean-August-Dominique Ingres’s (1780–1867) portraits staged in London, Washington, and New York in 1999, followed by major retrospectives in Paris and, on a more modest scale, Madrid, in 2006 and 2015, respectively, one would seemingly be hard-pressed to find new grounds for organizing yet another major loan exhibition devoted to the celebrated but ever-embattled master from Montauban.[1] Yet that is precisely what curators at the Musée Condé in the Château de Chantilly did, skillfully orchestrating a relatively small but visually stunning exhibition around the theme of Ingres’s relationship with members of the Orléans dynasty, the last royal family of France. This exhibition was all the more valuable in that it featured important canvases belonging to the Musée Condée—works that, because of the rigorous non-lending policy of that institution, have not been subjected to the same degree of scholarly and curatorial scrutiny as works included in the landmark exhibitions listed above.

At first glance, the physical circumstances of the exhibition seemed anything but propitious. The show was mounted in the Château’s cavernous tennis court building on relatively low walls temporarily installed for the occasion; one could see the upper fragments of works permanently displayed in the space on the walls beyond (fig. 1). Seemingly even more inauspiciously, little natural light infiltrated the space through the building’s high curtained windows, requiring all the works in the exhibition to be illuminated by spotlights strategically placed around the hall. Yet, to my eyes, the works on display had never been so thrillingly visible! In addition to impeccable lighting, this effect was largely the felicitous result of the consistently low hanging of the works (fig. 2), which allowed even this relatively modestly scaled (5’6”) visitor to confront the figures in most of the paintings more-or-less head-on. Many of the works on paper were likewise displayed at a slight incline on roughly waist-high tables (fig. 3), thereby inviting visitors to linger over them instead of being seduced by the full-color fare on the walls beyond. Thus, despite the challenges presented by the physical limitations of the venue, the exhibition could not, in my opinion, have been more effectively mounted.

The exhibition was divided into a succession of small, alcove-like spaces (fig. 4), each focusing on a single work or group of works together with the usual array of contextualizing material in the form of preparatory studies, variations, and replicas, as well as a not-so-expected abundance of both graphic and photographic reproductions. Although the conceptualization of the show was essentially monographic, organizers did not hesitate to include works by hands other than Ingres. His celebrated early portrait of Madame Duvaucey (see fig. 12), for instance, was accompanied by a roughly contemporaneous portrait of the sitter’s paramour, Charles-Jean-Marie Alquier, by Jean-Baptiste Wicar (1762–1834) (see fig. 14). Three painted versions of Ingres’s Paolo and Francesca (see figs. 15, 16, 17) were joined by renditions of the same theme by the French painter Marie-Philippe Coupin de La Couperie (1773–1851) as well as the English draftsman John Flaxman (1755–1826). And, in what was perhaps the most ambitiously wide-ranging section of the exhibition, Ingres’s 1840 painting Stratonice (see fig. 18) shared its gallery with the Prix-de-Rome painting on the same theme by his master Jacques-Louis-David (1748–1825) (see fig. 19) as well as Paul Delaroche’s (1797–1856) L’assassinat du duc de Guise (Assassination of the Duke of Guise, see fig. 20). I will have more to say about that painting’s relationship to Stratonice below.

As already noted, the underlying theme of the exhibition was the patronage Ingres enjoyed from members of the Orléans family. This began in 1833 when Ferdinand-Philippe (1810–42), duc d’Orléans, the popular and debonaire eldest son of King Louis-Philippe (1773–1850), commissioned the painting that eventually became Stratonice. While waiting for this work to be delivered, the duc purchased Oedipus and the Sphinx (1808–27, visible in fig. 1) at public auction in 1839. Then, following the stunning success of Stratonice when first exhibited in Paris in 1840, the duc d’Orléans commissioned his own portrait (fig. 5), a work that Ingres managed to complete in record time and just weeks before the prince perished in a carriage accident in July 1842. This tragedy prompted not only the commissioning of myriad copies of Ingres’s portrait of the much-regretted heir to the throne (see fig. 2) but also cartoons for the stained-glass windows of the memorial chapel erected on the spot where he lost his life as well as for the Orléans dynastic chapel at Dreux (fig. 4).

The other member of the Orléans family to contribute majorly not so much to the actual unfolding of Ingres’s career as to the spread of his posthumous fame was Henri d’Orléans (1822–97), the duc d’Aumale, younger brother of the duc d’Orléans and owner of the Chateau de Chantilly. D’Aumale obtained his first work by Ingres, a version of Paolo and Francesca (see fig. 15) originally painted for Caroline Murat (1782–1839), Napoleon’s sister and, for a short while, Queen of Naples, in 1854. Nine years later, the duc d’Aumale purchased Stratonice at public auction for the then astounding sum of 92,000 francs. Then, in 1879, he acquired three of Ingres’s greatest paintings—the stunning Self-Portrait at the Age of Twenty-four (fig. 6), the Portrait of Madame Duvaucey (see fig. 12), and Venus Anadyomène (see fig. 24)—as part of his purchase en bloc of the paintings collection of Frédéric Reiset (1815–91), a longtime friend and supporter of Ingres who had just stepped down as director of the national museums.

While the commissioning and collecting activities of the ducs d’Orléans and d’Aumale provided the exhibition with its major thematic focus, the attention that it placed on the four major works in the permanent collection of the Musée Condé constituted for me the exhibition’s principal contribution to our ever-evolving understanding of Ingres’s artistic achievement. It is on these works and the excellent analyses of them in the exhibition catalogue that I will focus for the remainder of this review.

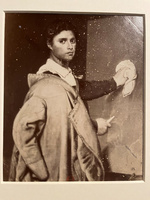

Ingres’s Self-Portrait at the Age of Twenty-four (fig. 6) could well qualify as a quintessential statement of Romantic creative autonomy, albeit somewhat paradoxically, given the artist’s reputation as classicism incarnate.[2] Of the works in the Musée Condé, it has received by far the most attention from scholars.[3] Yet, in contrast to its current fame, the canvas was exhibited to universal derision upon its public debut at the 1806 Salon. As has long been recognized, the appearance of the portrait in 1806 was quite different from its present state, which seems to have been achieved around 1850 when Ingres radically reworked the canvas.[4] The original—or, at least, near original—state of the portrait was represented in the exhibition by a copy made in 1807 at Ingres’s request by his soon-to-be ex-fiancée, the professional painter Julie Forestier (1782–1853), and given to the artist’s father (fig. 7). The unprecedented juxtaposition of both works in the Chantilly exhibition inevitably led organizers to grapple with the vexed issue of the self-portrait’s evolution. The most clarifying contribution to existing debates was provided by the conservation report included in the catalogue (39–43). Various forms of technical analyses carried out on the Chantilly painting by the Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France (C2RMF) confirmed the existence of the original composition beneath its current surface; technical analyses suggested as well that both the face of the artist and the foreshortened easel in the lower right-hand corner that we see in the Chantilly painting today were parts of the original composition, these sections showing no evidence of subsequent repainting. If this is indeed the case, then the photograph of the painting taken by Charles Marville around mid-century, one print of which was included in the exhibition (fig. 8), may well reproduce not an earlier version of the Chantilly canvas, as most scholars—myself included—have previously believed,[5] but the Forestier copy instead. Such is the conclusion reached by Florence Viguier-Dutheil, Director of the Musée Ingres-Bourdelle in Montauban, in a perceptive and carefully argued essay on the portrait in the exhibition catalogue (21–36). There is one glaring difference, however, between the Marville photograph and the Forestier copy: the canvas in the former shows the chalk outlines of Ingres’s unfinished portrait of his childhood friend Jean-Pierre-François Gilibert (fig. 9), while the canvas in the latter is blank. Interestingly enough, the outline of Gilibert’s portrait also appears on the surface of the canvas in the self-portrait in another reproduction that scholars have widely believed to document an early stage in the evolution of the Chantilly canvas: the unique proof of an unpublished print retouched and annotated by Ingres (fig. 10). This print has long been attributed, albeit sometimes with reservations,[6] to Ingres’s friend and acolyte, Jean-Louis-Potrelle (1788–1824), who also made a print after Ingres’s 1805 portrait of the Italian sculptor Lorenzo Bartolini (1777–1850), which may have been the intended pendant to the Self-Portrait at the Age of Twenty-four in its original state. Unfortunately, the etching, which belongs to the Musée Ingres-Bourdelle, was absent from the exhibition; it was, however, included in the catalogue as unattributed and undated, with no mention of the earlier attribution to Potrelle.[7]

So, how to reconcile the varying candidates vying to represent the early version of the Self-Portrait? Viguier-Dutheil, taking up a suggestion first put forth decades ago by the great Ingres scholar Daniel Ternois, believes that the painter was prompted (temporarily) to incorporate into the Self-Portrait a reference to the portrait of Gilibert by the death of the latter in 1850. She speculates that Ingres tested out this idea by adding the outline of Gilibert’s portrait to the canvas in the etching and in the Forestier copy. He then had the latter photographed by Marville before ultimately deciding to return that canvas to its original state (30–33). That Ingres would be prompted by Gilibert’s death to incorporate a reference to his portrait when reworking his self-portrait around 1850 is indeed intriguing. That he would have added it to the Forestier copy, have had it photographed, and then have almost immediately deleted it, however, strains credulity, especially as this was also precisely the moment in which the artist made the radical decision to pivot the face of the canvas in the self-portrait away from the viewer and, concomitantly, to change the gesture of his left hand from wiping the canvas in front of him to resting it on his chest. Complicating matters further is a well-known later copy of the self-portrait in the Metropolitan Museum in New York (fig. 11), which also includes the outline of Gilibert’s portrait on the visible face of the canvas and restores the original wiping gesture;[8] moreover, this work, which is believed to have been executed under the close supervision of Ingres himself, was mentioned in a publication in 1861 as capturing the original appearance of the Self-Portrait at the Age of Twenty-four.[9] Thus, despite the invaluable discoveries made by the C2RMF and the astute observations offered by Vigier-Duthueil in the catalogue, the exact evolution of this extraordinary painting seems far from settled.[10]

The history of the portrait of Madame Duvaucey (fig. 12), which was among the first portraits Ingres completed upon assuming his residence at the French Academy in Rome in 1806, is a much more straightforward affair.[11] Its brief evolution was charted in the exhibition via a trio of preparatory drawings, including two particularly beautiful wash drawings, a medium for which Ingres is, to my mind, insufficiently appreciated. As noted in the catalogue, the portrait of Madame Duvaucey was first publicly displayed at the Salon in 1833, in which Ingres’s celebrated portrait of the newspaperman Louis-Francois Bertin (fig. 13), completed one year earlier in 1832, was also exhibited. Commentators at the time wondered if Ingres included both works in the same Salon as a rather self-indulgent demonstration of the evolution of his style from 1807 until 1833. And, indeed, I found myself regretting the absence of the portrait of “Monsieur Bertin” from the Chantilly exhibition, as it deprived its visitors of the same opportunity to compare Ingres’s early and mid-career portrait styles. The juxtaposition that the exhibition did provide, between Madame Duvaucey and Wicar’s decidedly old-fashioned portrait of her protector (fig. 14), served to point up how extraordinarily original and innovative Ingres’s vision as a portraitist was at this very early stage in his career.

The Musée Condé’s version of Paola and Francesca (fig. 15), which was executed in 1814 for Murat, making it Ingres’s earliest painting of this theme, was joined at Chantilly by two others: one from the Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Birmingham, England (fig. 16), a close replica of the Chantilly painting that is probably similar in date; and a much later version, probably from the mid-1840s, currently in the Hyde Collection in Glens Falls, New York (fig. 17). While some visitors might have regretted the absence of perhaps the most celebrated of Ingres’s renditions of this theme—the elaborately detailed panel painting from 1819 currently in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Angers—the decision to feature two less frequently exhibited works from rather out-of-the-way collections struck me as well-founded. This section of the exhibition also featured three of Ingres’s highly finished compositional drawings of Paolo and Francesca as well as several preparatory drawings for the paintings, including a pair of lovely graphite studies for the body of Francesca from the Musée Ingres-Bourdelle in Montauban.

Although not particularly celebrated today—a function undoubtedly in part of its inability to travel—Stratonice (fig. 18) was considered one of Ingres’s signature achievements during his lifetime.[12] As demonstrated in the characteristically bold and provocative essay on the painting in the catalogue by Georges Vigne and on the walls of the exhibition itself by the inclusion of David’s painting on this theme (fig. 19), Ingres was by no means the first artist to treat the subject of the near fatal lovesickness of the Assyrian prince Antiochus for his beautiful stepmother, Stratonice. He was, however, the first to bring to the treatment of this subject a high degree of pseudo-archaeological exactitude, something he accomplished with the aid of the young architecte-pensionnaire and future chief architect to the city of Paris, Victor Baltard (1805–74), who was responsible for researching and designing the elaborate décor of the prince’s bedchamber in which Ingres’s drama unfolds.[13] As noted above, the painting was the result of a commission from the duc d’Orléans, who, in a display of princely magnanimity, left the subject up to Ingres. And while the circumstances surrounding this connection remain somewhat cloudy, Ingres was clearly compelled to bring his work into accord with a painting commissioned by the duc d’Orléans at the same time from Paul Delaroche: L’assassinat du duc de Guise (fig. 20). This painting, which created a sensation at the 1835 Salon, has precisely the same dimensions as Stratonice (57 x 98 cm) and is very similar in format, lighting scheme, and overall composition. It seems likely that Delaroche’s obsessively detailed interior of the duc de Guise’s sixteenth-century bedchamber also prompted Ingres, seconded by Baltard, to take an equally exacting approach to the bedroom setting of Stratonice. Yet Vigne, former director of the Musée Ingres and arguably the foremost authority working on the artist today, resists identifying the paintings as actual pendants, noting that neither the duc d’Orléans nor the duc d’Aumale ever hung them side-by-side (116–17). Similarly, the organizers of the exhibition distanced the two paintings in their installation, pairing Ingres’s painting for the duc d’Orléans with a similarly scaled but much later version of Stratonice now in the Musée Fabre in Montpelier (see fig. 3). While this pairing, like the emphasis on multiple iterations of the same subject throughout the exhibition, demonstrated the organizer’s preoccupation with Ingres’s alleged lifelong quest for perfection—a subject, it should be noted, that was explored rather exhaustively in a US exhibition of the artist’s many repetitions way back in 1983[14]—an opportunity to more clearly understand the relationship between Stratonice and the Duc de Guise seems to have been missed. For whatever reluctance the ducs d’Orléans and d’Aumale may have shown to displaying the works together, there can be no doubt that Ingres had the latter foremost in mind when composing the former. Thus, a more thoroughgoing examination of the relationship between the two works seems very much in order.

As outlined by Vigne in the exhibition catalogue, Ingres’s preoccupation with the subject of Stratonice predated by decades the commission he received for the Chantilly painting in 1833. The artist initially began thinking about the subject at the beginning of the century in Paris while waiting to assume his residency at the French Academy in Rome. This phase of Ingres’s engagement with this theme is documented by a number of highly finished drawings, most notably a duly famous (if not uncontroversial)[15] sheet in the Louvre (fig. 21) as well as a recently rediscovered and closely related wash drawing (fig. 22) that entered the Kunstmuseum Bern as part of the notorious collection of Cornelius Gurlitt (1932–2014), the reclusive son of one of Hitler’s art dealers who is believed to have trafficked in looted art, in 2014. (The Kunstmuseum claims to have accepted only works from the collection that were proven not to have been looted.) In the catalogue, Vigne makes the compelling suggestion that the Bern drawing may have been the sheet sold by Ingres to the Danish collector Tønnes Christian Bruun-Neergaard (1776–1824) at the beginning of the century. However, inscriptions on the back of the drawing, unmentioned by Vigne but included in the catalogue entry on the drawing, claim that it was given by Ingres himself directly to Madame Charles Dupaty (142, cat. 30). This was the wife of the sculptor Charles Dupaty (1771–1825), Prix-de-Rome laureate of 1799 whose portrait Ingres had drawn in 1810 (fig. 23).[16] Moreover, one of the inscriptions is signed E. Hecquet d’Orval; this is almost certainly a direct descendant of Mme Dupaty’s older sister—the inscription identifies Madame Dupaty as Hecquet d’Orval’s aunt—who married the manufacturer Jean-Pierre Hecquet d’Orval in 1812. And here it should also be noted that it was from the collection of a descendant of this same family, Nadine Hecquet d’Orval (1925–2005), wife of Jean-Noel, Comte de Lipkowski, that Ingres’s portrait of Dupaty emerged in 1974.[17] Obviously, the only way for Ingres to have given the Bern drawing to Madame Dupaty after having sold it to Bruun-Neergaard would be for him to have gotten it back from the Danish collector at some point; and indeed, Bruun-Neergaard’s collection was auctioned in Paris in 1814. Yet Ingres was still in Rome at this time, making it highly unlikely that he could have purchased the drawing then. Thus, Vigne’s ingenious suggestion to the contrary, the identity of the Bruun-Neergaard drawing remains something of a mystery.[18]

The history of the evolution of the fourth major painting by Ingres in the Musée Condé is hardly less complicated than that of the Self-Portrait at the Age of Twenty-four: Venus Anadyomène (fig. 24). This work was initially begun as one of Ingres’s required envois while a pensioner at the French Academy in Rome but was ultimately abandoned for this purpose in favor of the famous Valpinçon Bather (1808) now in the Louvre. Ingres took up the work again for a prospective client in Florence in the early 1820s only to abandon it when he made the sudden decision to remain in Paris, where he had gone to escort the reputation-changing Vow of Louis XIII to the 1824 Salon. The sketch of Venus Anadyomène was damaged while being shipped back to France and languished unfinished in Ingres’s studio for another twenty years until the artist finally completed it in 1848 for the noted collector Benjamin Delessert (1773–1847), who quickly sold it to Reiset, from whom it was purchased by the duc d’Aumale.

Like the Self-Portrait at the Age of Twenty-four, Venus Anadyomène was subjected to rigorous technical examination by the C2RMF prior to the Chantilly exhibition, and its findings, reported in the exhibition catalogue, provide a more precise understanding of the painting’s forty-year evolution (229–34). In an insightful essay in the catalogue, Côme Fabre, curator at the Louvre, argues intriguingly that a heretofore unrecognized key stage in the painting’s development occurred in the early 1820s in Florence, when Ingres effectively rejected the more mannerist approach to the female nude he had initially adopted in Rome for the much more classical, neo-Renaissance treatment of the figure in the final painting—a stylistic shift that Fabre attributes to the artist’s simultaneous engagement on the emphatically Raphaelesque Vow of Louis XIII (209–24). Venus Anadyomène was accompanied in the exhibition by a number of preparatory studies and studio repetitions as well as the closely related painting La Source (fig. 25), which was completed amidst much fanfare in 1856, but whose origins also stretched back to the early 1820s.

Three additional highlights of the exhibition had only tenuous connections to the organizing theme of Ingres’s relationship to the Orléans dynasty. These included the large, mysteriously fragmented painting of Virgil Reading the Aeneid (1819) from the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique in Brussels, which Garnier-Pelle speculates provocatively in the catalogue could at one time have been destined for yet another of Louis-Philippe’s sons, Antoine d’Orléans (1824–90), duc de Montpensier (197–98). Then there was the large drawing of Homer Deified (1865), a late reworking of the theme of Ingres’s most celebrated history painting, The Apotheosis of Homer (1827), which had originally been commissioned by the government of the Bourbon Restauration to decorate the ceiling of one of the rooms in the Musée Charles X in the Louvre. The drawing’s inclusion in the present exhibition was justified on the grounds that the duc d’Aumale had tried doggedly but unsuccessfully to purchase it from Ingres’s widow (246–47). Finally, and most spectacularly, radiating from the carefully coordinated blue walls of the final section in the exhibition was, for my money anyway, Ingres’s most glorious creation: La Comtesse d’Haussonville of 1845 (fig. 26). Included here on the grounds that its sitter belonged to the upper echelons of the Orléanist elite, the picture normally hangs in the Frick Collection in New York, which, until relatively recently, was, like the Musée Condé, a strictly non-lending institution, with the result that the Chantilly exhibition constituted only the second time that Ingres’s masterwork had been exhibited on French soil in well over a century.[19] Its presence at Chantilly was thus undoubtedly reason enough for many to visit the exhibition. And indeed, to my eyes, the picture never looked more beautiful or beguiling, fully justifying the naughty quip allegedly made to the comtesse by the politician Adolphe Thiers upon the portrait’s private unveiling in 1845: “Monsieur Ingres must have been in love with you to have painted you in such a manner.”[20]

Notes

[1] See Gary Tinterow and Philip Conisbee, eds., Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum/Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1999); Vincent Promarède, Stéphane Guégan, Louis-Antoine Prat, and Éric Bertin, eds., Ingres (1780–1867), exh. cat. (Paris: Gallimard/Musée du Louvre Éditions, 2006); Vincent Pomarède and Carlos G. Navarro, eds., Ingres, exh. cat. (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2015).

[2] See Uwe Fleckner, “Quand l’autoportrait glisse hors du temps: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres se peint lui-même” in Ingres, Un Homme à part? Entre carrière et mythe, la fabrique du personage, Actes du colloque École du Louvre, 25-28 avril 2006, ed., Claire Barbillon, Philippe Durey, and Uwe Fleckner (Paris: École du Louvre, 2009), 19–28.

[3] See, for instance, the extensive analyses of this work in Tinterow and Conisbee, Portraits by Ingres, 35–37, 72–75, and 454–58.

[4] The painting is illustrated in its current state in Albert Magimel, Oeuvres de J.-A. Ingres, membre de l’Institut, gravées au trait sur acier par A[chil]le Réveil, 1800–1851 (Paris: Firmin Didot Frères, 1851), pl. 1. The appearance of this publication thus provides a terminus ante quem for the reworking of the Chantilly painting.

[5] See, for instance, Tinterow in Tinterow and Conisbee, Portraits by Ingres, 457n8, where slight variations between the Forestier canvas and the Marville photograph are noted.

[6] See, for instance, Tinterow in Tinterow and Conisbee, Portraits by Ingres, 456, and Georges Vigne, Ingres: Autour des peintures du musée de Montauban, 36. Most recently, the etching’s attribution to Potrelle was somewhat cautiously upheld in Mehdi Korchane, ed., Ingres avant Ingres: Dessiner pour peintre, exh. cat. (Orléans: Musée des beaux-arts, 2021), cat. 16.

[7] An additional reason for associating the etching with an early phase in the evolution of the self-portrait is provided by the sketches and notes it contains relating to Ingres’s own face. If this part of the portrait was never altered after 1804, as conservators contend, then it seems highly unlikely that Ingres would be trying out alternatives for this area of the canvas circa 1850.

[8] See Gary Tinterow’s extensive catalogue entry on this work in Tinterow and Conisbee, Portraits by Ingres, 454–58.

[9] Emile Galichon, “Description des dessins de M. Ingres exposés au Salon des Arts-Unis”, Gazette des beaux-arts 9, no. 6 (March 15, 1861): 359–60: “Cette copie est conforme à la première pensée du maître (This copy conforms to the master’s original conception).” This claim can be only partially true, as this copy replaces the bulky tan overcoat hanging rather limply from the artist’s shoulder in the original version of the Self-Portrait with the infinitely more dashing brown carrick of the Chantilly painting.

[10] For a very different account of the evolution of the Self-Portrait at Age Twenty-four and its relationship with the portrait of Gilibert, see Andrew Carrington Shelton, “Ingres, Painter of Men,” Art History no. 44, 1 (February 2021): 16–51. This article seems to have escaped the attention of the organizers of the Chantilly exhibition.

[11] As noted in the catalogue entry for this painting, however, evidence of a second signature and the possible date of 1808 was found beneath the repainting of the armchair during a recent restoration, suggesting that Ingres could have reworked the canvas around this time. See Deldicque and Garnier-Pelle, Ingres, 73, cat. 10.

[12] On the stir created by the arrival and initial display of this painting in Paris, see Andrew Carrington Shelton, Ingres and his Critics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 54–86. Long excerpts from several particularly sycophantic articles on the painting penned by the minor artist and journalist Jules Varnier are included in the catalogue; see Deldicque and Garnier-Pelle, Ingres, 132–33.

[13] Two preparatory drawings attributed to Baltard (cat. 56) and to Baltard and Ingres together (cat. 55) were included in the exhibition. On the young architect’s contributions to the project, see Alice Thomine-Berrada, “Une Histoire d’amitié, de peintre et d’architecte: Baltard et Ingres autour de la Stratonice,” in Deldicque and Garnier-Pelle, Ingres, 135–40.

[14] See Patricia Condon, Marjorie Cohn, and Agnes Mongan, In Pursuit of Perfection: The Art of J.-A.-D. Dominique Ingres, exh. cat. (Louisville: The J.B. Speed Art Museum/Indiana University Press, 1983).

[15] The authenticity of the Louvre drawing was somewhat notoriously called into question by Hélène Toussaint in 1980; see Hélène Toussaint, “Rémise en cause de deux célèbres dessins du Louvre, Portrait de femme et Antiochus et Stratonice,” in Actes du Colloque Ingres et son influence, Bulletin spécial des Amis du Musée Ingres (Montauban: Ateliers du Moustier, 1980), 157–71.

[16] On Dupaty, see Hans Naef, Die Bilniszeichnungen von J.-A.-D. Ingres, 5 vols. (Bern: Benteli Verlag, 1977–80), I: 206–13, a text initially published in English in Hans Naef, “The Sculptor Dupaty and the Painter Dejuinne: Two Unpublished Portraits by Ingres,” Master Drawings 13, no. 3 (Autumn 1975): 261–74 and 323–25. Charles Dupaty married his niece, Annette-Paméla Cabanis (1800–80), in July 1823. Ingres’s portrait drawing of Dupaty was last seen in the sale of the collection of A. Alfred Taubman at Sotheby’s, New York, on January 27, 2016, lot 67.

[17] See Naef, “The Sculptor Dupaty,” 266.

[18] Organizers of the 2006 Ingres retrospective in Paris identify the Louvre drawing as the sheet having belonged to Bruun-Neergaard (and later to the painter Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson); see Pomarède, Guéguan, Prat, and Bertin, Ingres, 117, cat. 8.

[19] The portrait was included in the 2006 retrospective in Paris. See Pomarède, Guégan, Prat, and Bertin, Ingres, 348–49, cat. 158.

[20] Ingres recorded Thiers’s remark in a letter dated June 28, 1845 to his longtime friend and supporter, Charles Marcotte. See Daniel Ternois, Lettres d’Ingres à Marcotte d’Argenteuil (Nogent-le-Roi: Librairie des Arts et Métiers/Éditions Jacques Laget, 1999), 125: “il faut que M. Ingres soit amoureux de vous pour vous avoir peint ainci!”