Napoleon’s Plunder and the Theft of Veronese’s Feast by Cynthia Saltzman

Reviewed by Todd PorterfieldTodd Porterfield

Professor

New York University

Email the author: todd.porterfield[at]nyu.edu

Citation: Todd Porterfield, book review of Napoleon’s Plunder and the Theft of Veronese’s Feast by Cynthia Saltzman, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 2 (Autumn 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.2.13.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Cynthia Saltzman,

Napoleon’s Plunder and the Theft of Veronese’s Feast.

London: Thames & Hudson, 2021.

300 pp.; 14 color illus.; 31 b&w illus.; bibliography; notes; index.

£25.00 (hardcover), £12.99 (paperback).

ISBN: 9780500252574

The intended public for Cynthia Saltzman’s 2021 Napoleon’s Plunder and the Theft of Veronese’s Feast is a bit of a puzzle. By French standards, it is une grande fresque, less likely to land on a curator’s shelf or a professor’s syllabus than on a television executive’s pitch desk for a future miniseries. Middlebrow, it offers information, entertainment, and storytelling, moved along by an abundance of period citations. From Renaissance Venice and Napoleonic France to the Covid years, its historical sweep is dotted with pleasing vignettes rendered in smooth prose. Red-letter Revolutionary events like the Flight to Varennes are explained. Good Friday is not. The product of extensive research produced by an international team, Napoleon’s Plunder offers sparse, partial, and unanalytical attention to the subject’s historiography. That Paolo Veronese’s (1528–88) monumental painting, the 1563 Wedding Feast at Cana (fig. 1), was made on contract (36) is presented with a note of marvel to a public whose familiarity with the most common takeaways from Michael Baxandall’s classic Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy is not assumed.[1]

Still, over the course of Saltzman’s twenty-two chapters, there are many good things. The most informative, delightful, and gripping sections of the book are found in the pivotal chapter 10 in which Veronese’s masterpiece is targeted for expropriation in the summer of 1797. In granular detail Saltzman introduces three of the saga’s most compelling characters: Claude Berthollet (1748–1822), chemist and director of the Gobelins tapestry manufactory, dispatched to Venice to obtain the twenty works ceded to France in the Venetian surrender; his local interlocutor, Vincenzo Dandolo (1758–1819), also a chemist, son of a Jewish pharmacist, translator of Lavoisier’s Traité élémentaire de chimie (Elements of Chemistry, 1789), Jacobin member of the French-friendly Provisional Municipal government, who delegated the task of facilitating the canvas’s handover to the chapter’s third major character, the inspector general of the Serenissima’s artistic holdings from 1770 to 1817, Pietro Edwards (1744–1821), an Irish-Catholic Venetian and a celebrated and pioneering painting restorer, who, Saltzman relays, restored over 759 paintings in his career.

With characters introduced, the author sets them in motion in a set piece that weaves together the banality of administration with the cat-and-mouse games of figures doing their jobs, driven by love of art and patrie. Arriving in Venice from Florence, Berthollet ducks the Venetian Edwards to determine his own list of sixteen paintings to expropriate, independent of Venetian advice. French administrators approve his list, which Saltzman then evaluates according to the targeted works’ quality and location in the city. When the narration arrives at the sixth painting, The Feast, the point of view shifts, and Saltzman’s dry account of the list gives way to Edwards’s outrage. In a report to the French-friendly Venetian Committee of Public Safety, Edwards asks for four of the works, including The Feast, to be left in situ because of their fragile condition, but his request is refused.

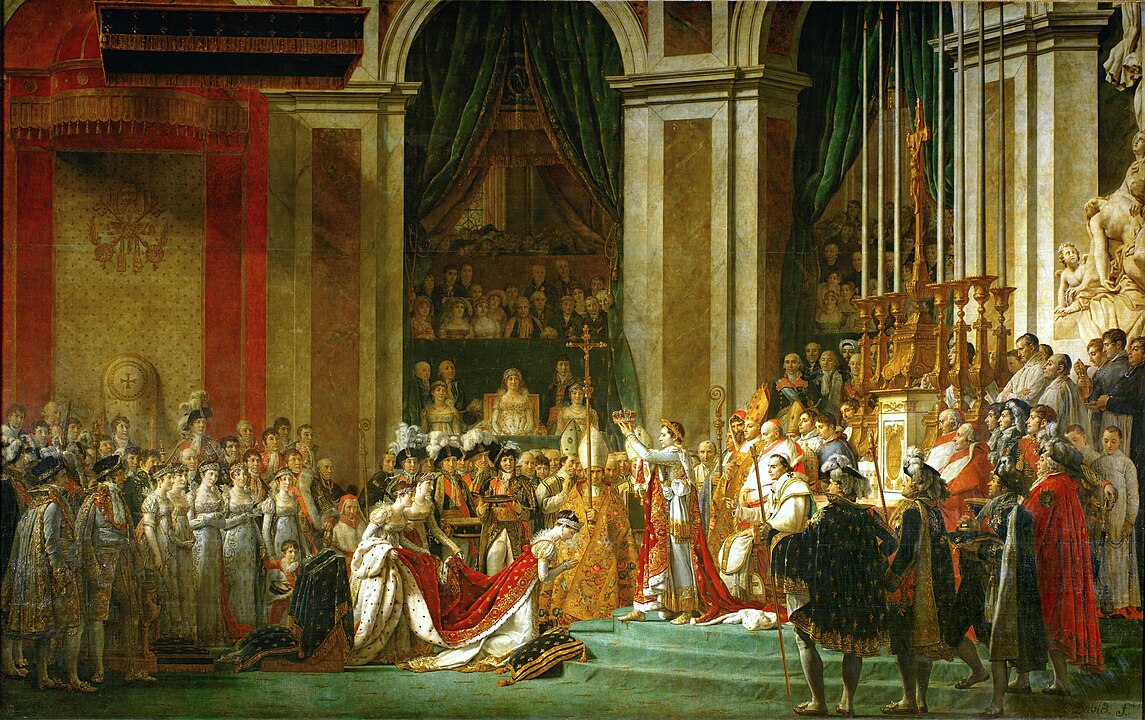

After Saltzman and the French forces get The Feast to the Louvre in 1801, the author devotes several chapters to the political and artistic context of The Feast’s use and reception in France and, above all, to its influence on French painting, notably upon Jacques-Louis David’s (1748–1825) Coronation of Napoleon and Josephine (fig. 2), the subject of chapter 17. It exemplifies the book’s limitations. While Saltzman celebrates The Feast for its painterly bravura and Veronese as a paragon of artistic independence, French paintings, most of them undoubtedly inferior to the Veronese, serve the text as transparent historical illustrations, propelling the reader from one historical event to the next.

Along the way Saltzman falls into a trap set by David more than two centuries ago.[2] At an early 1808 special exhibition, David placed a mirror across from the Coronation to co-opt spectators into participating in, affirming, and naturalizing the foundational moment of an authoritarian regime. In the same vein, a Parisian newspaper ran an anonymous article, probably planted by David, that attributes to Napoleon the often-repeated compliment, “on marche dans ce tableau” (“one walks in this canvas”).[3] Saltzman takes the Davidian bait, repeating another critic’s observation that at the 1808 Salon viewers blended into the sparkling scene, seeming to intermingle with the figures in the picture, evidence, it would seem, of the gallantry, palpability, and verve bequeathed to David by Veronese.[4] Saltzman’s hagiographic approach, however, ignores the critic from the 1802 Journal des débats who had described Veronese’s role as art history’s “first official painter,” who did not ignore the “mechanism” of the state, and, rather than being the model of an independent artist, was instead “a great and marvelous decorator.”[5] In the end Napoleon’s Plunder is uneven-handed in its aesthetic judgments, not given to pursuing the implications of its material, indifferent to political and scholarly debates, and willing to cultivate distinctions that are later ignored in order to give the book a happy ending.

In the epilogue, the tone of lament in Napoleon’s Plunder gives way to an ode to the transcendence of art and the triumph of Western modernism. During The Feast’s perilous adventures over two centuries of restorations, removals, and reinstallations, the fate of the painting becomes tied to France’s own geography and survival. Under Nazi threat in 1939, The Feast made a circuitous and clandestine journey through France where it was hidden in historic castles, palaces, and monasteries dating from the twelfth to the seventeenth centuries.

The Feast’s precarious existence and its misplacement in Paris and not Venice is ostensibly redeemed in Saltzman’s compact recapitulation of Western painting from the time of Giotto. Traversing the galleries of the Louvre and the Orsay, she narrates a familiar evolution of Western painting, in which David, Antoine-Jean Gros (1771–1835), and Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), notwithstanding their contradictions, are all “heirs to Veronese” and “pioneers of modern art,” whose contributions lead inexorably to Vincent van Gogh (223). What was celebrated in the 1983–84 landmark exhibition as The Genius of Venice is now concentrated in the figure of Paolo Veronese (1528–88), symbol of artistic genius tout court.[6] In his canvas in which Christ turns water into wine, the Renaissance artist demonstrates the “ability to conjure flesh-and-blood figures moving about in space and the texture of embroidered silk and light playing over it with no more than brushstrokes of paint,” so that “the canvas became a metaphor for the chance painters take to transform and to transfix experience, to shape life into art” (231–32).

While Saltzman’s art history is hackneyed, it is also timely because it provides an opportunity to consider some of our discipline’s most current and vital questions. On one of the most vibrant subject areas in recent scholarship, the material culture of art’s making, the author provides some of her most satisfying passages with practical details such as the width of the looms on which Veronese’s canvas was woven, the gauge of the weave, and even the estimated weight of the canvas used in the painting. The subject of Venetian colorism yields comments on the global trade in pigments and the Venetian distribution system via vendecolori (color merchants) rather than through pharmacies.

On the forever subject of freedom and autonomy, Veronese and Venetian painting are emblems and agents. Saltzman accords the French-mandated July 1797 closing of Venice’s nearly three-hundred-year-old Jewish Ghetto, characterized as a “concrete step toward liberty” (114), only a passing mention, for in her account it is Venetian Renaissance art and the medium of oil on canvas that are freeing. In traditional art histories, the rise of oil on canvas as a medium in the Renaissance leads to discussions of the mobility of the art object and its independence from specifications of wall, architecture, and sponsoring institution, but the irony should be noted. The mobility that Saltzman values when Veronese is working alone in his studio, away from the eyes and control of patrons, is the same mobility that facilitates The Feast’s forced removal to the French capital.

To underscore Veronese’s artistic heroism, Saltzman returns us to the pleasing set piece of the artist’s 1573 appearance before the Inquisition (50–53). Accused of heresy for his Last Supper, the artist famously defended himself by simply changing its title to The Feast in the House of Levi. Saltzman, however, does not acknowledge that this spirit of rebellion only became part of his artistic reputation after 1867, when Armand Baschet rediscovered the transcript of the closed-door hearing, nor does she acknowledge Paul H. D. Kaplan’s assessment that “there is no record of any serious disputes with his [Veronese’s] patrons and no evidence of any independent or unorthodox ideological position with regards to religious theory or practice.”[7] Notwithstanding nineteenth-century hagiography, Veronese was ultimately a painter of brilliant but obedient pictures.

On the question of democratic access to high art and cultural expropriation, the author gives a detailed account of The Feast’s original home in the Benedictine church of San Giorgio Maggiore, recounting the responses of Veronese’s glamorous public, mostly Benedictine, Venetian, and foreign ambassadorial and cultural elites (164). However, if access to Veronese’s painting is of concern, why not take into account the ideological program of the Revolutionary Louvre, where, each time the citizen entered the precinct, they crossed the nationalized threshold of what had been the deposed king’s palace, reenacted and reaffirmed the Revolution, and took possession of the treasures and the lessons of the past for an anti-feudal present and future. That model of access gets short shrift. When in the epilogue, Saltzman herself visits the Louvre to commune with The Feast, it is during the pandemic, “when the Louvre is officially closed and emptied of the public it was designed to serve.” She is as alone with the canvas and as isolated as a 1660 visitor to The Feast’s first home in the San Giorgio monastery on an island in the Venetian Lagoon. “This,” she writes, “is not Painting, this is magic” (231).

On the question of where a work belongs, of home, and of rightful return, Quatremère de Quincy’s 1796 Lettres à Miranda sur le déplacement des monuments de l’Italie (Letters to Miranda on the Removal of the Monuments from Italy) is summoned to testify against the universal survey museum, completely in keeping with our era’s tendency to insist on a work’s original, intended destination and cultural context as its rightful home.

Saltzman’s lament, however, does not include a full reckoning with the contemporary issue, which would have led necessarily to Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy’s 2018 Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain (Report on the Restitution of Africa’s Cultural Heritage).[8] They make a strong case for the return of African objects from French state museums to Africa, for, in their estimate, sub-Saharan Africa is unique in having had ninety to ninety-five percent of its artistic patrimony expropriated from the continent. Can Venice really be said to be similarly bereft? Although weighing loss and regret may be difficult, there are perhaps times when it is unseemly not to try.

Notes

[1] Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy: A Primer on the Social History of Pictorial Style (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972.)

[2] On Veronese’s Feast’s reception in France and use by Jacques-Louis David, see Todd Porterfield, “Illusory Access,” in Todd Porterfield and Susan L. Siegfried, Staging Empire: Napoleon, Ingres, and David (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006), 121–24, and notes.

[3] “Intérieur. Paris, January 15,” Gazette nationale ou Le Moniteur universel, January 16, 1808, 63–64; reprinted and translated in Appendix C, Porterfield and Siegfried, Staging Empire, 194–96.

[4] “Tableau du couronnement, par M. David,” Le Courrier de l’Europe (et supplément “Les Spectacles et la littérature”), February 12, 1808, 2–3.

[5] “Paul Véronèse n’ignorait pas le mécanisme; c’était, pour me servir de l’expression des artistes, le premier des peintre d’apparât, et [ce] que des gens qui parleraient pour être entendus de tout le monde, appelleraient un grand et merveilleux décorateur.” “Observations sur la nouvelle exposition”, Journal des débats, 1802; cited in Porterfield and Siegfried, 231.

[6] Jane Martineau and Charles Hope, The Genius of Venice, 1500–1600, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1983).

[7] Paul H. D. Kaplan, “Veronese and the Inquisition: the Geopolitical Context,” in Suspended License: Censorship and the Visual Arts, ed. Elizabeth C. Childs (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1997), 87.

[8] Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, “Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain,” Vie publique, November 29, 2018, https://www.vie-publique.fr/.