The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern

Grand Palais, Paris

October 9, 2019–January 27, 2020

Catalogue:

Stéphane Guégan ed.,

Toulouse-Lautrec: Résolument moderne.

Paris: Musée d’Orsay, RMN–Grand Palais, 2019.

352 pp.; 350 color illus.; chronology; exhibition checklist; bibliography; index.

$48.45 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978–2711874033

“Faire vrai et non pas idéal,” wrote the French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901) in a letter to his friend Étienne Devismes in 1881.[1] In reaction to the traditional establishment, constituted especially by the École des Beaux-Arts, the Paris Salon, and the styles and techniques they promulgated, Toulouse-Lautrec cultivated his own approach to painting, while also pioneering new methods in lithography and the art of the poster. He explored popular, even vulgar subject matter, while collaborating with vanguard artists, writers, and stars of Bohemian Paris. Despite his artistic innovations, he remains an enigmatic and somewhat liminal figure in the history of French modern art. His work does not fit neatly into any of the “isms” of his era, and he has not drawn as much scholarly attention as some of his peers. Now, however, a major retrospective has brought Toulouse-Lautrec into the spotlight. Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern at the Grand Palais is the first retrospective of the artist in twenty-seven years.[2] With over 200 works from museums and private collections around Europe and the United States, the exhibition affords a rare opportunity to observe in one place the extent of his oeuvre. The sheer number of major works in Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern is impressive and reveals the prolific nature of the painter. One cannot help but be overwhelmed by his inexhaustible artistic experimentation. The retrospective effectively demonstrates Toulouse-Lautrec’s seminal role as a modernist who captured “real” lived experience—the pleasures and tribulations of late nineteenth-century Paris.

The exhibition is arranged thematically and semi-chronologically in a sprawling, two-storied space at the Grand Palais. Divided into twelve sections, the layout showcases the wide range of genres Toulouse-Lautrec tackled along with the myriad personalities he captured during his brief but fertile career. Each section is demarcated with wall text that provides background information on his life and work. Timelines offer further context and biographical details. Photographs of iconic Montmartre sites, often blown up on an enormous scale, give viewers an impression of the venues that he frequented and painted. Unfortunately, many of these photographs lack captions. When labels do appear next to individual artworks, their small font makes them difficult to read, particularly as the exhibition is often teeming with visitors. Although the exhibition will attract an international audience, many of the descriptions are only in French. For French readers, the corresponding catalogue is indispensable. It is as impressively comprehensive as the exhibition, with essays written by an international group of scholars, a timeline with in-depth detail on Toulouse-Lautrec’s life and work, as well as a large selection of color plates. These plates are laid out thematically in approximately the same order as the exhibition with short essays that closely mirror the text in the exhibition. The catalogue is of great value for scholars as well as a broader readership.

The first section, entitled “Delighted by Everything,” touches on Toulouse-Lautrec’s early career and his penchant for all things modern—photography, cinema, electricity, and the technological developments that would shape his era (fig. 1). There are photographs of Toulouse-Lautrec in multiple guises, including one by Maurice Guibert entitled Toulouse-Lautrec with the Hat and Boa of Jean Avril (ca. 1892) of the artist at a costume party. The wall text describes Toulouse-Lautrec “as a devotee of cross-dressing,” stating that “he was diversely curious. Men, women, cultures, religions, sexualities: he was attentive to all of them. When he posed, Lautrec changed his age, sex, or continent . . . within his playful use of photography lay a desire to paint all things.” In addition to his curiosity, one wonders why Toulouse-Lautrec was drawn to masquerade. Was it because it allowed him to playfully and momentarily transcend his gender, social class, and physical disability? Suffering from pycnodysostosis, a genotypic bone disorder, and as one of the few artists from the aristocracy working in Bohemian Montmartre, he was unusual in many ways.[3] Did cross-dressing enable him to better relate or empathize with his subjects? Scholarship in disability studies has reclaimed the artist’s impairment as a newly productive lens and has offered fresh insight into his oeuvre.[4] This, however, is not a framework developed in any depth in this exhibition.

“A Fierce Naturalism,” the title of the following section, refers to Toulouse-Lautrec’s commitment to painting the world as he saw it, with an unflinching eye. The wall text provides information on his early training and career. In Paris, he studied with the painter René Princeteau, who was also of noble birth and known for his paintings of horses.[5] An ambitious young artist with a rebellious spirit, Toulouse-Lautrec rejected the opportunity to study with the more prominent, academic painter Alexandre Cabanel. Subsequently, he worked in the studios of Léon Bonnat and Fernand Cormon. Early works, including nude sketches and portraits, are shown together to demonstrate his artistic development under their tutelage. Most striking is Toulouse-Lautrec’s Parody of the “The Sacred Grove” by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1884). It is hung next to the very painting it mocks, Puvis de Chavannes’s The Sacred Grove, Beloved of the Arts and Muses (1884), first shown at the Salon of 1884. Toulouse-Lautrec’s version includes a motley group of men who interrupt the otherwise idyllic, pastoral scene populated by muses. His own truncated silhouette is plainly visible. Brazenly, he depicts himself urinating, a gesture described as “desacralizing” by the curators. The painting demonstrates Toulouse-Lautrec’s rejection of the classical ideal and defiance of the time-honored values of the Salon and academicism.

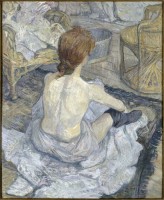

Female Nude (1884; fig. 2) is painted with similar stalwart realism. The model for the painting was Suzanne Valadon, who, amazingly, also posed for Puvis de Chavanne’s The Sacred Grove.[6] She was rumored to have been Toulouse-Lautrec’s lover for a short period (with no conclusive evidence). Valadon was in the early stages of her own artistic career around the time that she modeled for Toulouse-Lautrec. Unfortunately, the exhibition identifies her solely as a mistress and model. The wall text asserts that the painting is “probably the first masterpiece by the young Lautrec, a sort of manifestation of naturalism.” Valadon is shown slouched back in a chair in a pose that appears frank and nonchalant—the foil to an idealized, academic nude. The influence of Japonisme is evident in the inclusion of two Japanese masks. The work is in concert with the vanguard approaches to the nude that artists like Edouard Manet had spearheaded before him. In fact, Manet was an extremely important painter for Toulouse-Lautrec, who exclaimed around 1884, “Vive la révolution! Vive Manet!” (“Long live the Revolution! Long live Manet!”). Later, in 1890, he took part in the campaign to purchase Manet’s Olympia (1863) for the French national collection (34).

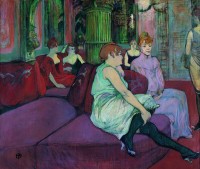

Valadon is highlighted in the next gallery, along with Carmen Gaudin and Jeanne Wenz. The portraits and toilette scenes Toulouse-Lautrec painted of Gaudin are magnetic. In Carmen Gaudin (ca. 1884), she faces but looks past viewers with an expression of assurance and determination; a rim of red fringe crowns her head. Redhead (1889, presumed to be Gaudin; fig. 3) displays her from behind in an untidy room. The angled viewpoint, piles of clothing, and tub recall Degas’ bathers. Like Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec pioneered new methods and materials. Rather than canvas, he frequently employed cardboard, which absorbs and dilutes the oil medium, giving it a matte appearance. The brushstrokes are semi-transparent, almost resembling watercolor. Like many other pieces in the show, this work is from the permanent collection of the Musée d’Orsay. The exhibition affords a unique opportunity to see pieces such as this one that are rarely on view, perhaps due to the fragile nature of the material. Another work that may represent Gaudin is Woman Combing her Hair (1891). Toulouse-Lautrec paints as if a draughtsman; a closer look at the cardboard surface reveals a tangle of brushstrokes of vivid color weaving in various directions.

By the late 1880s, Toulouse-Lautrec was beginning to exhibit his work with greater frequency, but only in progressive and non-traditional venues. In 1886, the wall text notes, “in an act of open provocation, he submitted a still life featuring a camembert cheese to the Salon.” (This painting, perhaps lost, was not displayed). In 1887, he showed his work alongside that of Vincent Van Gogh, Louis Anquetin, and Émile Bernard at the restaurant Au Grand Bouillon, and the group was dubbed the “petit boulevard impressionists.” Toulouse-Laturec’s Portrait of Vincent van Gogh (1887) attests to their friendship and speaks, through its style and technique, to their artistic collaboration. The portrait was exhibited at the Salon des XX in February 1888 along with nine other paintings, including At the Cirque Fernando (1887–88; fig. 4). This circus scene features a redheaded woman on a horse, her skirt flaring upward in a manner that mirrors the animal’s buoyant tail. The exaggerated perspective and foreshortening of the horse’s hind legs give a sense of dizzying speed, while the animal’s hooves nearly scrape the frame. Overall, there is an arresting sense of whirling, chaotic motion. The wall text describes the painting as having “feminine” and “masculine” features. Yet, it seems that Toulouse-Lautrec is interested in capturing the spellbinding excitement of the circus first and foremost. His sketches of the circus displayed in the same room reinforce this. They appear like improvised doodles and pay special attention to bodily distortion and movement.

Viewers pass by a magnified photograph of the Moulin Rouge before entering a gallery entitled “Capital Pleasure” (fig. 5). Here, Toulouse-Lautrec’s images of the music halls, café-concerts, cabarets, and their entertainers take center stage. The wall text posits that “Lautrec understood the poetic and commercial potential of Montmartre’s entertainment venues,” and that he “[analyzed] human desire in those places” to reveal “animality and eccentricity.” In 1891, he made his first advertising poster for the Moulin Rouge, and after, he made a series of posters that consolidated his fame. Moulin Rouge—La Goulue (1891) features the star Louise Weber, known as La Goulue (the Glutton), on the dance floor caught in the mid-movement—one leg thrusted into the air, her petticoat a ball of white light before a crowd reduced to black shadows. She dances her signature “chahut,” a raucous version of the cancan that both shocked and fascinated audiences. The grey, silhouetted profile of Valentin le Désossé (Valentin the Boneless) appears in the foreground. He lifts his right hand in a suggestive manner, his thumb pointing toward her thighs. However, he is merely a framing device; La Goulue is the star. The hallmarks of Toulouse-Lautrec’s style, from the flattened areas of color, bold forms, the two-dimensionality of space, and exaggerated perspective, are evident, and they simultaneously recall Japanese woodblock prints. In the wall text, curators once again identify the “masculine” and “feminine” qualities of the image, but to my mind Toulouse-Laturec is more concerned with sensations of movement and the energy experienced at the Moulin Rouge. Among the many posters in this section is Aristide Bruant in his Cabaret (1893), which depicts the singer and cabaret proprietor at the theater Les Ambassadeurs and adorned the wall of Bruant’s nightclub, Le Mirliton. The proofs are displayed along with the final poster. According to the wall text, it was rare for artists to keep proofs, and therefore these demonstrate the importance of the poster to the artist. Here, it would have been informative to learn more about the step-by-step process of poster making at this time and the new technologies and advancements in lithography. At the New Circus, Papa Chrysanthemum (1894–95) reveals the influence of Art Nouveau with its use of sinuous lines, as well as Toulouse-Lautrec’s experimentation in diverse media, in this case stained glass. Viewers learn that it was produced in collaboration with Louis Comfort Tiffany. From the Orsay collection, this piece deserves more frequent display in the museum’s permanent galleries.

The exhibition affords the opportunity to see important works by the artist from museums outside France, such as Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette (1889) and At the Moulin Rouge (1892–95; fig. 6), both from the Art Institute of Chicago. In the latter, the artist appears with his friends, including the dancer La Macarona, photographer Paul Secau, and La Goulue. Toulouse-Lautrec’s presence in the image demonstrates his empathy and sense of belonging in this bohemian realm. The wall text emphasizes that Toulouse-Lautrec “did not aim to stigmatize the pleasures of Paris,” but equally impressive in this work is the artist’s interest in electric lighting, as Holly Clayson has recently pointed out.[7] The distortions caused by its artificial glare are plainly evident in his depiction of May Milton, a nightlife star, who appears in the foreground. Resembling a phantom with her acid green features and yellow-orange hair, her face is lit from below so violently that it almost disfigures her. With this accent on non-naturalistic lighting, Toulouse-Lautrec captures the eerie, drunken, and enigmatic milieu of Montmartre at night.

La Goulue takes center stage in the section entitled “La Goulue’s Grand Finale.” We are told that “Lautrec was seduced by her cocky vitality, and she inspired his paintings and lithographs” for several years, including the aforementioned Moulin Rouge–La Goulue (132). When her popularity waned, she left the Moulin Rouge and established her own show at the Foire du Trône, in 1895. She commissioned Toulouse-Lautrec to create two monumental panels for the façade of her stall at the fair, entitled The Dance at the Moulin Rouge (1895; fig. 7) and The Moorish Dance (1895). A wall text explains that La Goulue sold the panels in 1900, and an unscrupulous art dealer cut them into fragments that were later salvaged and reassembled. With its bold silhouettes, flattened forms, and large empty spaces of exposed canvas, the diptych marries the art of painting with that of the poster. Moreover, the work demonstrates the artist’s support for pioneering women launching their own careers, while the appearance of Oscar Wilde in one of the panels shows his embrace of figures persecuted for challenging social norms. Toulouse-Lautrec depicted Wilde several times, including on the night before Wilde’s trial for gross indecency in London in 1895. The diptych was painted that same year.

Viewers walk in between the two panels, as if re-entering La Goulue’s fairground tent, into the next room entitled “For All to Read” (fig. 8). This space is devoted to Toulouse-Lautrec’s literary collaborations, in particular, his involvement with the avant-garde magazine La Revue blanche beginning around 1893. A group of posters and lithographs for the magazine and other publications, including illustrations for Jules Renard’s Histoire naturelles, Henry Nocq’s Tendances nouvelles, and Zola’s La Curée leave the viewer somewhat puzzled. It is also baffling to see a film by Jean Renoir of the Moulin Rouge, French Cancan (1955), adjacent to this section on literature. Fortunately, the exhibition regains its focus downstairs. We learn about yet another nightlife star, Yvette Guilbert (fig. 9). Toulouse-Lautrec discovered her at the Divan Japonais in 1890, and subsequently depicted her in numerous sketches, posters, and lithographs. In the poster Divan Japonais, 75, rue des Martyrs (1893), she is cropped at the neck and recognizable only by her black gloves. The wall text describes her as a “storyteller and singer” whose “repertoire, by turns bawdy and satirical, contrasted with her elegance: the long, slender, black-gloved arms, the green satin dress on her slim figure, the décolletage.” The plates for an album dedicated to her are shown, as well as preparatory sketches related to them. With her slender and knobby frame, short wispy hair, and signature black gloves, Guilbert appears somewhat androgynous and almost caricatured. Toulouse-Lautrec shows her from every angle, as if this illusive and spirited woman refused to be fully captured by the artist.

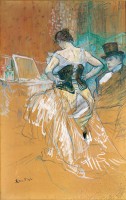

Not long after, Toulouse-Lautrec made a series of lithographs for another album entitled, Elles (1896), this time featuring prostitutes. These appear in the subsequent gallery, entitled “The Eternal Feminine.” As is well-known, he was a habitué of brothels. Toulouse-Lautrec brings the world of the brothel and the private lives of prostitutes to life in a fascinating range of poses and settings—lounging in common areas, eating in the refectory, preparing for medical exams, dressing or undressing, and at their toilettes. The wall text emphasizes that “Lautrec’s view into the maisons closes is free of all arrogance and cynicism . . . and self pity.” This is particularly evident in The Ladies in the Refectory (1893–95), a quotidian scene of women dining together in the brothel. A sense of extreme solitude and even melancholy pervades the image. Blonde Prostitute, Study for the Medical Examination (ca. 1893–94) displays a prostitute vulnerably awaiting inspection. Seemingly free of sexuality or desire, the image exposes the everyday, gritty realities in the life of a prostitute. In At the Salon of the rue des Moulins (1894; fig. 10), women loll against crimson cushions, idly waiting for customers. Contrary to what is stated in the wall labels, these images are not entirely devoid of voyeurism. In fact, there is a profound sense of the male voyeur’s presence in several works. For example, in Conquest of Passage, Study for Elles (1896; fig. 11), a male customer ogles a woman as she unties her corset. In the Bed (1892) is an intimate scene of two women. Although they appear androgynous, Toulouse-Lautrec affords a rare glimpse into the most private moments of these women’s lives. Undoubtedly, it is an image constructed for male pleasure and speaks to male fantasies about lesbianism.

Toulouse-Lautrec’s images of “fast-paced” subject matter, such as horses, dancers, and bicyclists, are the subject of the following gallery. Early works appear, including Artillery Man Selling his Horse (1879) and Nice, Memory of the Promenade des Anglais (1880). These images would have been better seen in relation to the tutelage of Princeteau, who was partly responsible for Toulouse-Lautrec’s interest in equestrian scenes. Nearby, Jane Avril appears in the poster, Mademoiselle Eglantine’s Troupe (1896), produced on Avril’s request for her show at the Palace Theater. Like a group of galloping horses, the chorus of dancers lifts their legs in unison in a lively cancan. In a separate, darkened room, the famous film of Loie Fuller produced by Pathé Frères plays. Although Fuller fascinated Toulouse-Lautrec, she reportedly did not take much of an interest in the artist, and the two never met. His sketches and lithographs appear on the wall opposite the film (fig. 12). Toulouse-Lautrec employs a sinuous line to capture her organic, billowing dress so miraculously caught in the film. He eliminates all but the essential details so that her form becomes a frenzied and vivid whirlwind.

Toulouse-Lautrec lived his fast-paced life to the fullest, but its excesses, particularly with alcohol consumption, began to take their toll toward the end of the century. By 1897, his friend Edouard Vuillard noted in his diary that Toulouse-Lautrec experienced “frequent attacks of instability” (43). In the wake of a series of violent outbursts, his family committed him to a clinic in Neuilly in 1899. There, he produced a series of thirty-nine drawings of circus scenes, depicting, as the catalogue notes, clowns and horses “dramatically staged in an arena of empty seats, whose curved lines clearly conjure a sense of confinement” (220). Other late works on display include portraits of Miss Dolly, a waitress at the Star, Maurice Joyant, and Paul Viaud. The saturated hues and feverish brushstrokes in the portrait of Paul Viaud demonstrate his continued mastery in capturing turbulent movement. The final works presented in the exhibition are sketches of the clowns Footit and Chocolat, At the Circus: Chocolat (1899) and Chocolat Dancing (1896). Background for these works is provided earlier in the show in the section on la Goulue. There, the timeline mentions that in 1895 Toulouse-Lautrec frequented the “Irish and American Bar on rue Royale and the Cosmopolitan American Bar on rue Scribe, where he met the famous clowns Foottit and Chocolat.” Besides this brief reference, no further information is provided. Chocolat (the Cuban Rafael Padilla) and Foottit (the English-born Tudor Hall) performed together at the Nouveau Cirque. In these shows, it was often Chocolat who was beaten and mocked by Foottit.[8] A film by the Lumière brothers of the two clowns in action is displayed above the sketches. Without context, these images are troublesome. They recall the minstrel shows that were popular in Europe and the United States during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Although the curators emphasize Toulouse-Lautrec’s ability to identify with his subjects and to depict them without scorn or criticism, these particular images undermine their argument. Of course, Toulouse-Lautrec was a product of his time, and he did not fully escape the pervasive stereotypes around the black figure in his representations of Chocolat. Ironically, the recent exhibition, Le modèle noir de Géricault à Matisse, also curated by the Musée d’Orsay, sought to rectify longstanding misconceptions about the black figure in art while also demonstrating the importance of black people in art history.[9] This new framework might have illuminated more fully the images of Chocolat. Also, as one sketch of Foottit shows him not as a clown, but as a ballerina dressed in a leotard, this gallery brought the exhibition, perhaps unwittingly, full circle, back to the theme of cross-dressing and Toulouse-Lautrec’s embrace of nonconformity.

Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern is a landmark exhibition: the task of locating, selecting, and assembling approximately two hundred of Toulouse-Lautrec’s works in diverse media from around the world was a tremendous undertaking. I have noted some of the difficulties it presents. The order and arrangement of some works does not fully correspond with the theme or time period of the section in which they are placed, but of course a strictly thematic or chronological organization would have had its own limitations. Other works merit further analysis and contextualization. Nevertheless, the retrospective and accompanying catalogue will undoubtedly spark further scholarship on this well-known, yet understudied artist. In addition to Toulouse-Lautrec’s enigmatic personality, part of his appeal for viewers must be the relevance of his work today. His innovations in the art of the poster still bear their mark on advertising. His depictions of the nocturnal world and modern entertainment ignite imaginations and draw visitors to Paris. His delight in everyday subjects, society’s outsiders, and his attention to previously taboo themes, such as homosexuality, deeply resonate with viewers now, over a century later. The exhibition successfully underscores Toulouse-Lautrec as a pioneering modernist who captured, better than any of his contemporaries, the Bohemian realm of Montmartre with its eccentric personalities and loosened mores, as well as the turbulence and excitement that so characterized the Belle Époque.

Lauren Jimerson, PhD

Independent Scholar

lauren.jimerson[at]gmail.com

[1] “Make what is true, not what is ideal.” Wall text in the exhibition at the Grand Palais and translated by author.

[2] Produced by the Musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie and the Réunion des Musées Nationaux—Grand Palais with support of the city Albi and the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec. Curated by Stéphane Guégan (conseiller scientifique auprès de la présidence de l’Établissement public des musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie) and Danièle Devynck (director of the musée Toulouse-Lautrec). The last major retrospective was in 1992 and had as its catalogue: Gale B. Murray, Toulouse-Lautrec: A Retrospective (New York: Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, 1992).

[3] On his disease, see K. Markatos, A.F. Mavrogenis, M. Karamanou, and G. Androutsos, “Pycnodysostosis: the Disease of Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec,” European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology: Orthopedie Traumatologie 28.8 (2018): 1569–72.

[4] Alexandra Courtois de Vicose, “‘The Monstrous Gnome’: Confronting Physical Difference in the Art of Toulouse-Lautrec,” (PhD diss., University of California at Berkeley, 2018); “Deaf Gain: Toulouse-Lautrec and his First Teacher René Princeteau” in Disability and Art History, vol. 2, ed. Ann Millet-Gallant and Elizabeth Howie (London: Routledge, forthcoming).

[5] One point not made is that like Toulouse-Lautrec, René Princeteau also had a disability—he was deaf. Alexandra Courtois de Vicose has recently explored their relationship in a forthcoming chapter in “The Monstrous Game.”

[6] Lauren Jimerson, “Defying Gender—Suzanne Valadon and the Male Nude,” Woman’s Art Journal (Spring 2019), 5.

[7] Hollis Clayson, Illuminated Paris: Essays on Art and Lighting in the Belle Époque (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2019).

[8] Céline Debray, Stéphane Guégan, et al., Le Modèle noir: de Géricault à Matisse (Paris: Flammarion and the Musée d’Orsay, 2019), 191.

[9] Céline Debray, Stéphane Guégan, et al., Le Modèle noir: de Géricault à Matisse, 191.