The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

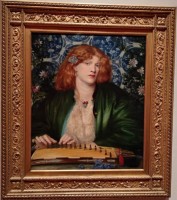

Pre-Raphaelite Sisters

National Portrait Gallery, London

October 17, 2019–January 26, 2020

Catalogue:

Jan Marsh and Peter Funnell,

Pre-Raphaelite Sisters.

London: National Portrait Gallery Publications, 2019.

207 pp.; 143 color illus.; bibliography; index.

$45.58 (hardcover); $32.49 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781855147270

ISBN: 1855147279

The first exhibition devoted exclusively to the contribution of women to the Pre-Raphaelite movement opened in the National Portrait Gallery in London in October. It sheds light on the role of twelve female models, muses, wives, poets, and artists active within the Pre-Raphaelite circle, which is revealed as much less of an exclusive “boys’ club.” The aim of the exhibition was to “redress the balance in showing just how engaged and central women were to the endeavor, as the subjects of the images themselves, but also in their production,” as stated on the back cover of the catalogue accompanying the exhibition. Although there have been previous exhibitions on the female artists associated with the movement, such as in Pre-Raphaelite Women Artists (Manchester City Art Galleries, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Southampton City Art Gallery, 1997–98), the broader scope of this exhibition counts models and relatives among the significant players within art production and distribution. This approach makes Pre-Raphaelite Sisters exceptional as it addresses female agency within their historical circumstances, not according to Procrustean male archetypes.

The first large exhibition to attempt an overview of Pre-Raphaelite art production was held by Tate Britain in 1984. As is described in the catalogue Pre-Raphaelite Sisters, like most other exhibitions since then, “women appear signally absent from Pre-Raphaelitism, except as subjects and models turned muses. In fact, however, women were active in all phases of the movement. Their presence had been obscured by structural or contingent causes, which still impede critical analysis of the art production” (10). It is precisely these contingent causes that should be laid bare in order to fully understand both the movement’s origins, its developments, and subsequent receptions of it. The way in which women have been represented both as subjects and inspirations to male artists has been thoroughly colored by social and ideological conditions (186). This highly complex structural discrimination begs for an alternative way to present art history.

The exhibition was curated by Jan Marsh, author and curator specialized in the Victorian period and particularly the Pre-Raphaelites. She has done extensive research into the women of the movement, which has resulted in several exhibitions and publications, such as The Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood, Pre-Raphaelite Women Artists, The Legend of Elizabeth Siddal, and biographies on Christina Rossetti, Jane and May Morris, just to name a few.[1]

The catalogue that accompanies the exhibition is a lavishly illustrated and well-written publication, containing chapters on all twelve women included in the exhibition and five thematic chapters, written by different authors. It is a true supplement to the exhibition. Where the exhibition is not the place for in-depth historical contextualization, the catalogue provides insights into structural problems, such as the position of female models between 1850 and 1900, male favoritism in the artworld, gender bias, and the activities of artists’ wives. The light shed on these marginalized elements shows the collaborative enterprise of the Pre-Raphaelite movement and debunks the myth of the single genius artist. Despite talent and individual hard work, all artists needed an extensive support network in order to make a career, of which many women were an essential part. This exhibition and catalogue urge us to critically revise our perception of art history and the position of marginalized figures such as women, particularly those that occupied unconventional positions.

The exhibition is divided into twelve sections, again separated into two parts, with a small intermezzo in between (fig. 1). Each section is dedicated to one woman who played a significant role in the Pre-Raphaelite movement, respectively Euphemia (“Effie”) Millais, Christina Rossetti, Elizabeth Siddal, Annie Miller, Fanny Cornforth, Joanna Boyce Wells, Fanny Eaton, Georgiana Burne-Jones, Maria Zambaco, Jane Morris, Marie Spartali Stillman (fig. 2), and Evelyn de Morgan. They are roughly presented in chronological order of their dates of birth. The exhibition starts with a wall text with a series of questions where the visitor is invited “to explore the creative contribution of women in the Pre-Raphaelite circle,” focusing on their own artistic ambitions and personal lives. What the roles of model, muse, wife, and artist contained is explained on a banner inside the exhibition. Although these explications are perhaps obvious to some, to emphasize these categories shows their importance for Pre-Raphaelite discourse. Nevertheless, the less straightforwardly defined roles, such as that of pupil, “studio manager” (admittedly an anachronistic term), and perhaps business partner are not explicitly mentioned in this list.

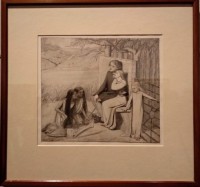

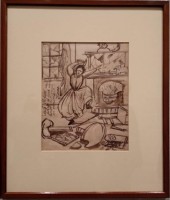

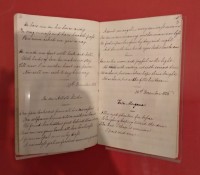

There is a wide variety of media on display. The combination of painting, drawing, photography, manuscripts of letters and poems, clothing, and other everyday objects shows not only the artistic output of these women but also grounds them in historical reality. Some of the artistic highlights are Ecce Ancilla Domini! (1850) and (a version of) Proserpine (1874) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Edward Burne-Jones’ The Tree of Forgiveness (1882). But besides these well-known Pre-Raphaelite icons, there were many other underappreciated treasures, such as Thou Bird of God (1861; fig. 3) by Joanne Boyce Wells, Madonna Pietra degli Scrovegni (1884; fig. 4) by Marie Spartali Stillman, and Night and Sleep (1878; fig. 5) by Evelyn de Morgan. I would like to single out one artist, namely Elizabeth Siddal. Many of Siddal’s intimate works are shown in the exhibition, including Lovers Listening to Music (1854; fig. 6) and Clerk Saunders (1857). Although much of her oeuvre has not survived, these works, along with a manuscript of one of her poems and a lock of hair, give us a sense of her own personal life and artistic activities.

Naturally, Siddal is best known as Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s model and one of the faces of Pre-Raphaelitism. This exhibition aims to reassess modelling as an important profession in its own right and an indispensable part of artistic production. This particular topic has recently gained prominence in both exhibitions and publications. Most of the women presented in Pre-Raphaelite Sisters made a living with modelling, and as with any other profession, this should be taken seriously. Its importance is emphasized repeatedly and pays tribute to this important contribution of women to art history.

Fanny Eaton is one example in question. Both she and some of her children modelled for many of the (late) Pre-Raphaelite artists, such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, Ford Madox Brown, Albert Moore, and Rebecca and Simeon Solomon, but also for the Royal Academy of London. Several of these paintings are shown together for the first time in this exhibition (figs. 7, 8). Eaton was of Jamaican descent and emigrated to Great Britain with her mother. Her distinguished looks made her attractive for many artists who wanted to depict Orientalizing Biblical, Egyptian, or Indian scenes. Eaton’s image serves as a connection between these artists. In the catalogue this topic is explored more fully. For instance, we read that models were often spotted in the streets or introduced through associates, and that artists would often share their models to cut costs. Moreover, this is how many models met other artists and were taken up in certain artistic circles (17). Regrettably, barely any of Eaton’s own documents have survived, making it difficult to construct a more personal account of her experiences (109).

As is well-known, modelling was also often associated with loose morals and prostitution in Victorian times. The stereotype that evolved became even more constricting because of the roles these women played in the paintings they modelled for, particularly that of “fallen” or “loose” women. The last chapter in the catalogue, by Allison Smith on the legacy of Pre-Raphaelitism in later times, explicitly discusses this “conflating the real with the imaginary” to which Pre-Raphaelite women fell victim (182). An example of this is Fanny Cornforth’s appearance in Thoughts of the Past (1859; fig. 9) by John Roddam Spencer-Stanhope. In this painting, Cornforth is shown in a bedroom in a nightgown, her hair down and a rather melancholic look on her face, as if contemplating her fate. Many of the collaborations between artists and models did result in intimate relationships. Yet this is often presented unfairly. Due to strict Victorian rules of propriety, women who were alone with men in their private quarters were stigmatized as prostitutes, especially women from a poorer background. Coupled with “the double standard of sexual morality” that became common in the 1850s in Britain, unmarried women in artistic circles would have had a hard time escaping these biases (74).

In this context, I doubt whether these women actually were able to “transcend roles of harlot, princess and goddess,” as the catalogue and exhibition argue (6). It is only now that many of the women’s reputations are revised according to historical fact rather than Victorian gossip and morality. A case in point is Maria Zambaco, an artist and model with a Greek background who became involved with Edward Burne-Jones as a student and lover. The words of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, spoken after Zambaco’s affair with Edward Burne-Jones had ended, tellingly capture the way in which she was horribly typecasted in real life: “the Greek damsel [was] beating up the quarters of all her friends and howling like Cassandra.”[2] Prior to this event, Edward Burne-Jones had made a drawing of Zambaco as the tragic prophet from Greek mythology, Cassandra, who was considered insane by her own family.

Despite cases like these, the agency of these women in earning their own money and making their way in the artistic world as models (amongst other things) cannot be doubted. Within the Pre-Raphaelite movement, social mobility through marriage was a genuine option as shown by the cases of Jane Morris and Elizabeth Siddal. Unlike the ways this has often been presented in Pre-Raphaelite biographies, these women weren’t damsels in distress or evil seductresses but actual women wanting a better future for themselves.

What this exhibition also shows is that more and more women were making a career as artists. Women’s opportunities improved considerably during the second half of the nineteenth century: art academy regulations loosened, special art programs for women were founded, and more women than ever exhibited their art publicly at salons (100). The chapter “Beyond the Parlour,” by Pamela Gerrish Nunn, touches upon this. But the position of women artists in Victorian society is not discussed systematically. Rather, this is to be inferred from the individual cases of women presented in the exhibition, such as Joanna Boyce Wells. Boyce Wells enjoyed a very successful career but died after childbirth when she was only thirty years old. Evelyn De Morgan is another case in point represented in the exhibition. Part of the last Pre-Raphaelite phase, she developed her own distinct style and was the mind behind the partnership with her husband William De Morgan, an accomplished ceramist.

As is mentioned in the catalogue, their contributions are painfully absent from previous exhibitions on the Pre-Raphaelites. Yet they were a part of Pre-Raphaelite social circles, if not working in their distinct aesthetic. Perhaps this is so because women did not fit into the category of great artists. According to Edward Burne-Jones, De Morgan’s “figures are badly drawn,” and “[i]f this girl had left figure painting alone and gone about the world modestly and happily doing pretty views, cities, flowers and every beautiful thing she came across in nature, with a cheerful mind . . . she would have done admirable and useful work that would have been a pleasure to everybody. But these pictures are only a bore and an anomaly.”[3] This bluntly sexist statement reveals the genuine threat that Pre-Raphaelite women posed to men and how they “suffered from gender bias and critical neglect” (170).

Amongst other things, this was due to the view that it was improper for women to be openly ambitious about their career, to show talent publicly, and to receive praise. This was also embedded in women’s own thinking and behavior, as shown in Georgina Burne-Jones decision not to develop her artistic interests further or Boyce Wells’ reluctance to accept compliments about her work (88, 139, 150). John Ruskin is quoted stating that wood engraving of a male artist’s design is “far more useful and noble work than any other of which feminine fingers are capable.”[4] Essentially, it was a man’s natural position to earn money for the family, not a woman’s. If a woman did make money with her own efforts, this was considered improper towards her husband. This gendered model of division of labor within the household is based on a view of women’s “natural destiny” as reproduction machines, i.e. an essentializing of womanhood. Moreover, when they did want to become artists, their practice was often branded amateur, a hobby rather than a serious profession (97, 129, 160).

On top of these social constraints, a particular ideal image of woman is deeply embedded in the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic that has had profound consequences for women in the movement. Perhaps surprisingly, the ideals presented in these artworks were highly uncommon, even outrageous, in Victorian England. Elizabeth Siddal’s red hair, heavy eyelids, and very fair skin and Jane Morris’ long neck, big, curly hair, and tall physique were not considered beautiful traits. In a way, the Pre-Raphaelites commitment to a different kind of beauty revolutionized ideals of femininity and opened the door to alternative appreciations of it. The downside of this is an overemphasis on outward appearance, such as hair and facial features, rather than the women behind their looks. This is also enhanced by the generic titles of many works, such as Proserpine, where—as I mentioned before—these women are conflated with mythological or archetypical characters. As William Rossetti described Annie Miller as having “a mass of the most lovely blond hair,” but “no breeding, education, or intellect” and Fanny Cornforth was “ignorant and vulgar, but physically attractive, uninhibited, fun.”[5] This shows how these women were often reduced to their appearance at the cost of their intellect, emotional life, and personality. The fact that even Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s portrait studies can be interpreted as tropes of beauty (fig. 10) could help to explain why their names have not survived the test of time.

The exhibition at the Portrait Gallery aims to counter this by repeatedly showing the names of these women on the gallery walls and the text labels, as if to imprint them in the visitor’s memory. By doing this, the actual names behind these generalized beauties can come to the fore. Moreover, the exhibition explicitly focuses on personal episodes in the lives of these women, without presenting any generalized view of women’s positions at the time (as they differed greatly). This is done through anecdotal stories, such as a drawing of Christina Rossetti’s emotional tantrums (fig. 11), or letters by Fanny Cornforth to her husband. By letting these women speak for themselves through documents that speak of their personal life and experiences, we get a very different picture of their lives that is less romanticized or dramatized through the eyes of their (often male) contemporaries and successors.

Yet, these documents are often scarce, and this lack of available sources has colored scholarly research and popular depiction (67). In order to rewrite this history on egalitarian terms, further research needs to be conducted. Moreover, some of the projects started by these women, such as a proposed illustrated book by Siddal and Georgina Burne-Jones, were never finished. Because it never left the conceptual phase of production, this all-female artistic collaboration did not enter art history, even though the ambitions were there. This also shows the discrepancy between these women’s ambitions and the possibility of realizing them (33). Along with the disappearance or destruction of much of the women’s artistic output, such as Zambaco’s and Siddal’s, their oeuvres have shrunk considerably, despite evidence of their productivity in contemporary sources (153, 155). These issues are named and addressed in the catalogue. For an exhibition, this is a different story. One cannot show what is not there anymore. But despite this, the exhibition is surprisingly rich in material.

This richness extends to a variety in sources and multifaceted aspects of the women’s personal histories. Yet, the ideological underpinnings of the image of woman as such could have enjoyed more explicit attention. Particularly, Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s views of women and the Pre-Raphaelite ideal of beauty in general terms is underlit, if not neglected. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s work constitutes a large part of the exhibition, especially his meticulous, fine-lined drawings of Annie Miller (fig. 10), Fanny Cornforth (fig. 12), Christina Rossetti, Maria Zambaco, and Jane Morris (fig. 13). These works are presented as testimonies to the looks of these women. Nonetheless, Dante Gabriel Rossetti was by no means a neutral observer. These drawings show a very specific interpretation of his sitters and an idealizing vision of woman. This problem is not explicitly expressed in the exhibition, and notions of beauty endorsed by the Pre-Raphaelites—both men and women—are not analyzed in-depth in the catalogue either. The focus is instead on social patterns, Victorian morals, and institutional possibilities, rather than the implications of ideology and standards of beauty.

Although I fully appreciate the socio-historical approach taken in the exhibition, the fact that ideology plays a minor role is a loss. Especially considering that contemporary fascination with the Pre-Raphaelite movement is based on these (problematic) views on women, this aspect deserves more attention. Perhaps in order to rewrite the Pre-Raphaelite story, the makers of the exhibition wanted to steer away from Dante Gabriel Rossetti as an overtly dominant character in the traditional narrative. Yet, it cannot be denied that he was a driving force behind the movement and connected many of the artists and models. As much as others deserve the limelight now, he still is a main protagonist.

While Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s aesthetics do not feature prominently in the exhibition’s narrative, one of his most famous paintings is found on the poster and the catalogue cover, Proserpine, showing Jane Morris in her iconic Pre-Raphaelite glory (fig. 14). When I visited the exhibition in its opening days, this was the banner used outside the museum. Unfortunately, I think that the strength of the exhibition itself to construct a new Pre-Raphaelite narrative is slightly undermined by this choice of campaign image. This famous painting endorses an objectification of women as “ephemeral stunners” rather than individual women. Moreover, there were other options available that would have asserted women’s agency within the Pre-Raphaelite movement much better, for example, a work by a woman of a woman, such as Elgiva (1885) (fig. 15) by Boyce Wells. This was a successful painting at the Salon of 1855 that started Boyce’s career and showed promise of her talent. Whether Proserpine as “the most famous image of Jane Morris” was a response to popular demand or not, Boyce Wells’ “quintessential Pre-Raphaelite” portrait both in style and subject matter does seem more appropriate as a poster or banner image. Another suggestion would be the aforementioned Night and Sleep by De Morgan (fig. 5), which is both in size and execution as ambitious as other paintings in the exhibition, if not more impressive. I must add that more banners were placed outside the museum entrance after my visit, also showing some of the female artists’ work.

One very progressive yet simple strategy that was endorsed in the exhibition to secure a more neutral treatment of men and women is the consistent use of surnames, rather than the use of first names, nicknames, or pet names that has been the rule for female Pre-Raphaelites until now. Siddal is again a good case in point. Her friends and family affectionally called her “Lizzie” or “the Sid.” While it is highly unscholarly to use this name to refer to her, this has nevertheless become a commonality. In the exhibition, she is appropriately referred to as “Siddal,” in relation to her male contemporaries such as “Rossetti.” This seemingly minor choice shows how language use is one of the main tools to control a tacit narrative.

This does raise the problem of married women’s names. When women give up their own family name at marriage, it disrupts the continuity of their identity, which is—particularly in the case of artists—intimately related to their name as a brand. Cornforth is a very good example of how name changes throughout a person’s life can obscure their place in history. She was born Sarah Cox, changed her name to Fanny Cornforth herself, and underwent two additional name changes as a result of marriages. Moreover, married artists or brothers and sisters often compete for recognition by a shared surname, a competition that women have mostly lost (74).

One of the myths that this exhibition aims to criticize is the supposed devotion of models to their profession and the work of male artists, especially in the case of Elizabeth Siddal. It is often chronicled religiously that during one of the modelling sessions for John Everett Millais’ painting Ophelia (1851–52) the heating system for the bathtub in which Siddal was lying broke down. Nevertheless, Siddal didn’t move a muscle and suffered a severe cold for the sake of art. Rather than this self-sacrificing and—most of all—passive interpretation of events, this exhibition shows the active collaboration between different artists and models, male and female alike. Their commitment was not a pathological female condition but an ambition to advance in life.

Naturally, some of the rather dramatic life events and personal choices—adultery, breaking societal rules of behavior and dress, addiction, and the like—were indeed a part of the Pre-Raphaelite story. Yet in this exhibition these do not take center stage. Rather, they are somewhat neutralized by focusing on actual historical documentation and artistic and social accomplishments. The downside of this inattention to the mythical character of much of the Pre-Raphaelite anecdotes, particularly those surrounding Dante Gabriel Rossetti, is that the trivializing effects of these anecdotes on the reputations of many women, both during their lives and after their deaths, are not considered. For instance, Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s unfaithfulness to Siddal did play a significant role in her overall well-being and the choices she made. I believe that the Pre-Raphaelite story cannot be separated from these sensationalist accounts of events. Nevertheless, the elaborate embellishments should be taken with a grain of salt.

Another myth, which is by no means unique to Pre-Raphaelitism, is that of the male artist genius. During the first wave of Pre-Raphaelitism, the artist as a bohemian, extraordinary individual was embraced: artists, in this way of thinking, could not or did not want to live by the rules of society and had to break free from the earthly constraints of family life in order to reach their full potential (182). This is the way in which many of the Pre-Raphaelite men have been characterized in the literature, almost justifying their deviant behavior. Yet, as has been argued by Pierre Bourdieu and other theorists, the idea that great art springs only from the creative talent of a single individual is utterly misleading. Artistic success is also determined by circumstantial factors, such as financial means and social support. This represents a shift in the conceptualization of the art world: structural conditions for artistic creation should include relevant persons and events that would traditionally not be seen as central figures within art history, such as artist’s wives and lovers.

In the context of exhibitions like this, where the selection criteria are gendered, this view is implicitly endorsed. To give previously peripheral individuals center stage, particularly women, has on the other hand also received criticism. Mainly this has been in the form of complaints against overtly feminist approaches that tend to appreciate women’s activities solely because they were done by women. But, without essentializing womanhood, it can be argued that women’s experience in the art world was significantly different from men’s—and therefore worth studying separately—because different conditions applied to them.

In Pre-Raphaelite Sisters, both male and female perspectives are explained, as one cannot be understood without the other. For instance, the way in which women and men interacted and their distinct or overlapping ideals and ambitions had a profound effect on the other sex. Studying men is also essential to expose the reasons why women were excluded from the initial brotherhood—with perhaps the exception of Christina Rossetti, who promptly declined their offer to join. Amongst other things, this was due to the close homosocial bonds between men (57). Although a more in-depth analysis of this phenomenon is still to be explored, the chapter by Peter Funnell does cover “Brotherhoods & Artistic Masculinities,” and all texts pay considerable attention to the role of men in the individual lives of the twelve women. In the exhibition, a room is devoted to the important men in the movement (fig. 1) and the wall texts repeatedly mention their relationship to the women and objects discussed. The exhibition thus presents us with a very balanced and historical account of gender restrictions in Victorian England.

Another counterargument, which Alison Smith mentions in her chapter “The Sisterhood & Its Afterlife,” concerns the grouping of these women together as a “sisterhood.” This critique has been voiced by Peter Fuller, who argues it is anachronistic to present these women as such because it projects a contemporary “proto feminist” agenda onto the past (186–87). Although several of the women included in the exhibition—including Zambaco, Stillman, and Jane Morris—did live on “sisterly” terms with each other, mutually stimulating artistic ambitions and supporting long personal friendships, the women in the first part of the exhibition could perhaps better be described as rivals. Siddal, Miller, and Cornforth did not necessarily relate to each other in a sympathetic manner; jealousy and gossip is said to have influenced their judgments of each other. All were models to Dante Gabriel Rossetti at different or overlapping points in their lives and competed for his affection. Moreover, some of the women, such as Euphemia Millais, were not involved in any aspect of the lives of the other women, let alone on an intimate level. The catalogue does admit to this “retrospective appellation” of history (182). In this sense, the choice for this title can hardly be justified fully.

Yet, if we go back to the sources, we do find that women in the movement were self-reflective of their situation. In her poem In an Artist’s Studio (1850; fig. 16), Christina Rossetti, a successful, published poet during her lifetime, wrote about the way a male artist approaches his female model (most likely referring to her brother Dante Gabriel and Siddal): “[n]ot as she is, but as she fills his dream.”[6] In essence, Christina Rossetti reveals the male gaze (also anachronistic as a term) that treats a female model as an aesthetic ideal rather than an individual, which was inherent to the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

But the real question that remains is: did these women actually contribute significantly to the Pre-Raphaelite movement? Euphemia Millais is a great example of the role women played in artistic production, particularly her husband’s career. On top of regular house work and raising their children, she made appointments, received guests at their house and studio, hosted events, answered letters, sought for and prepared props and costumes for paintings, kept a list of work in progress, took care of models, and did the accounting. The fact that she did this for both her consecutive husbands—John Ruskin and John Everett Millais, respectively—shows her own willingness to take on these organizational tasks full-heartedly (50). In essence, Euphemia Millais was her husband’s professional manager. This could only be discovered when unconventional sources are included in art historical research. As is mentioned in the catalogue, “[t]racing household management offers important biographical clues in otherwise inadequately recorded lives” (145). The shift of focus onto the everyday lives of these women provides us with a different source of information that is essential to understand their contributions.

Fanny Cornforth’s influence on the development of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s art is yet another case where traditional views of the artistic genius have clouded our understanding of history. Cornforth and Rossetti lived and worked together between 1862 and his death in 1882, and she modelled for many of his most famous paintings, such as Bocca Bociata (1859) and The Blue Bower (1865; fig. 17). During their long acquaintance, Rossetti’s style of painting moved away from the early phase of Pre-Raphaelitism of meticulous, truth-to-nature detail and moral pretentions, to a celebration of beauty, particularly inspired by Cornforth, what has come to be known as “art for art’s sake” (82). Unfortunately, their tumultuous love life has overshadowed Cornforth’s role in this development and their artistic collaboration.

Lastly, there is Jane Morris. Her participation in the Pre-Raphaelite movement has proven to go beyond her love life and good looks. She was the head of the embroidery workshop of Morris & Co. and worked together on major artistic projects in the Red House with William Morris and other members of the movement, including women such as Siddal and Georgiana Burne-Jones. This could be almost considered an artists’ collective, where everyone was “sharing in the process of art production” (126). In the reception of Jane Morris’ life, her activities as an accomplished household manager and creative designer have been understated, to say the least (115–16).

Not only were these women actively involved in the activities of the Pre-Raphaelite circle, they were also essential in preserving its legacy. Georgiana Burne-Jones, for example, wrote her husband’s memoirs, published in 1904 (134). Other later generation women wrote many of the first biographies. In this way, they participated in shaping the reputation of the movement and securing its afterlife for generations to come.

Thus, at the basis of the systematic discrimination against women in art history are the power relations between these female protagonists, their male contemporaries, and later (often male) art historians. Men such as William Morris and William Holman Hunt “educated” the women of their choice—Jane Morris and Annie Miller respectively—to become their perfect wives. Still, these women were almost always significantly younger and from a poorer background. Miller was only eighteen when she met Holman Hunt. She was branded a “temptress” after Holman Hunt claimed she had been unfaithful to him, and his peers told the story in such a way that it seemed that he was Miller’s victim. But we have to keep in mind that these women wanted a life of their own rather than to be groomed by others to fit a predetermined mold (67). Even female scholars that wrote about the Pre-Raphaelites since the 1960s have been judged based on their looks rather than their scholarly skills (184).

In conclusion, the Pre-Raphaelite movement was thoroughly gendered. This means that the role women played as participators and feminine ideals deserves much more attention than it has received in the past. Many of the Pre-Raphaelites supported women’s artistic ambitions and welcomed radical ideas of equality, in opposition to the art academy and the reigning norms of behavior and propriety. Then again, their vision of womanhood was limited and constricting for many of the women involved and those influenced by its ideology later on. Moreover, women’s artistic endeavors were stimulated but often within the confines of amateurism, which resulted in their contributions not being taken seriously or assessed by the same measures as their male counterparts (182). That is to say that there is a profound tension at the core of Pre-Raphaelitism between the emancipation of women from the confinements of Victorian society and the direct consequences of new ideals of womanhood. While previous scholarship into women in the arts has already exposed gender bias and institutional discrimination, it is now time to do justice to these facts and rewrite art history on egalitarian terms. Pre-Raphaelite Sisters is a fantastic example of how this can be achieved.

Mariëlle Ekkelenkamp

Curator in Training, Van Gogh Museum

marielle.ekkelenkamp[at]gmail.com

[1] Jan Marsh, Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood (London: Quartet Books, 1985); Jan Marsh, Pre-Raphaelite Women Artists (Manchester: Manchester City Art Galleries, 1997); Jan Marsh, The Legend of Elizabeth Siddal (London: Quartet Books, 1989, 2010); Jan Marsh, Christina Rossetti: A Literary Biography. (London: Jonathan Cape, 1994); Jan Marsh, The Collected Letters of Jane Morris (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2012); Jan Marsh, May Morris: Arts & Crafts Designer (New York: Thames & Hudson and London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2017).

[2] Dante Gabriel Rossetti, January 23, 1869, as quoted in The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, ed. William E. Fredeman, 9 vols. (Cambridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2001–12), letter 69:9.

[3] Edward Burne-Jones, diary entry, June 12, 1897, as quoted in Mary Lago, ed., Burne-Jones Talking: His Conversations 1850–1898 Preserved by his Studio Assistant Thomas Rooke (London: Pallas Athene, 1981), 148–50.

[4] Georgiana Burne-Jones, Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, vol. 1 (London: Macmillan & Co., 1904), 233.

[5] William Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti Family Letters with a Memoir, vol. 1 (London: Ellis and Elvey, 1895), 203.

[6] Christina Rossetti, “In an Artist’s Studio,” in “Notebook of Christina Rossetti (Two of Six), December 18, 1856–June 29, 1858,” entry of December 19, 1856, manuscript in the British Library, London, shelfmark Ashley MS 1364 (2).