The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Among late nineteenth-century British authors, none possessed more power to fascinate than Robert Louis Stevenson. Invalided from an early age, Stevenson roamed the globe from Scotland to Samoa in a quest for health, generating a prodigious array of novels, stories, poems, and essays along the way. At the height of the writer’s fame and the depth of his illness, Augustus Saint-Gaudens created a profile portrait in bas-relief that would long outlive the sitter (1887–88; fig. 1). Modeled for personal pleasure, this image also served commercial and commemorative purposes in the years to come. A transatlantic network of friends formed the hub of its expanding audience in the US and UK; their admiration for writer and sculptor radiated outward in reproductions of and variations on the original work.[1] Conceived as a souvenir of friendship, Saint-Gaudens’s combination of words and image subsequently became a celebrity icon, a memorial tribute, and an artistic legacy. The death of Stevenson and the long illness and death of Saint-Gaudens precipitated this evolution and gave the sculpture ever-deeper resonance. Its history shows how private associations can promote public interest in a life portrait and mortality can alter its significance in both spheres.

Origins

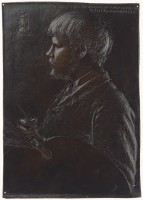

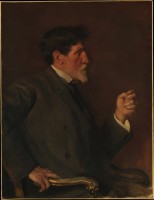

Saint-Gaudens’s portrait of Stevenson originated in a friendship among three artists with a common purpose. Born between 1848 and 1853, Stevenson, Saint-Gaudens (fig. 2), and Will H. Low (fig. 3), the painter who introduced them, were close contemporaries. Though their subject matter varied, they similarly sought imaginative expression and technical excellence in their art. All three men also retained a traditional respect for aesthetic ideals. They pursued their creative ends with the understanding, in Low’s words, that “Art is long; . . . [and] to reach the heights that others have attained, the route is stony and difficult.”[2] While study of the masters inspired writer, sculptor, and painter in their formative years, the other half of the ancient aphorism, “life is short,” informed their friendship. In Stevenson’s company one could not ignore the specter of death that hovers over even the most vital pursuit of art.

As a young art student in France in the 1870s, Low became the intimate associate of both Stevenson and Saint-Gaudens, men of distinct personalities. His introduction to the former took place in 1875 through the writer’s cousin, Robert A. M. Stevenson. Low recalled,

At the appointed hour there descended from the Calais train a youth “unspeakably slight,” with the face now familiar to us, . . . It was not a handsome face until he spoke, and then I can hardly imagine that any could deny the appeal of the vivacious eyes, the humour of the mobile mouth, . . . or fail to realize that here was one so evidently touched with genius that the higher beauty of the soul was his.[3]

Stevenson traveled frequently to the continent in the 1870s and 1880s to seek relief from tuberculosis, which was exacerbated by the climate of his native Scotland. He sojourned with Low in Paris and Grez-sur-Loing near Barbizon. Looking back upon these years, Low wrote, “The charm of his presence was both appealing and imperative, . . . Louis, quite unconsciously, exercised a species of fascination whenever we were together.”[4]

Low was not the only one to fall under Stevenson’s spell; others who knew the writer spoke of him in life-enhancing terms.[5] Andrew Lang said the young Stevenson “ran forth to embrace life like a lover.”[6] Edmund Gosse recalled his “gaiety”; Sidney Colvin, his “vitality”; stepdaughter Belle Osbourne, the “joyousness” he had brought into their lives.[7] For himself and for family, friends, and readers, Stevenson’s passion for living infused the world with possibility. Henry James declared, “He lighted up one whole side of the globe.”[8] Psychiatrist Kay Redfield Jamison ascribes Stevenson’s charisma to what she calls “exuberance”—“a mood or temperament of joyfulness, ebullience, and high spirits, a state of overflowing energy and delight.”[9] Though periods of ill health and depression sometimes dimmed his “frenzied enthusiasm,” Jamison explains, they served to “construct a ceiling of reality over skyborne ideas.”[10] In 1894, Stevenson wrote to Charles Baxter, his close friend and solicitor in Edinburgh, “I have been so long waiting for death, . . . I have done my fiddling so long under Vesuvius that I have almost forgotten to play, and can only wait for the eruption, and think it long of coming. Literally no man has more wholly outlived life than I. And still it is good fun.”[11] For Stevenson, the fact of death made the embrace of life more joyful.

While Low was captivated by Stevenson’s charm, he found Saint-Gaudens’s “straightforward simplicity” most impressive when the sculptor came to his Paris studio in the summer of 1877 to compliment him on a painting at the Salon.[12] The two artists had known each other previously through work and reputation, but they established what Low described as an “almost instantaneous footing of intimacy which between kindred spirits was not unusual in those days.”[13] Low saw much of Saint-Gaudens after their initial meeting and shared his studio for several months before returning to the US at the end of 1877. Saint-Gaudens kindled his new friend’s hopes for repatriation with talk of the recently formed Society of American Artists in New York. Though the sculptor was inclined to reticence and insecure about verbal expression, Low found he had “a gift of making one ‘see things’” when he felt passionately about a subject.[14]

Despite Low’s enthusiasm for Stevenson’s writing, Saint-Gaudens remained uninterested until the mid-1880s when another friend gave him a copy of The New Arabian Nights (1882). These fantastic tales “set [him] aflame as have few things in literature”;[15] almost overnight the sculptor became an avid reader of the Scotsman’s works. Saint-Gaudens told Low that if Stevenson ever came to the US he would be honored to meet him and to make his portrait. The opportunity finally arose in September 1887 when Stevenson, accompanied by his wife, Fanny, mother, Margaret, and stepson, Lloyd Osbourne, passed through New York City en route to Dr. E. L. Trudeau’s tuberculosis sanatorium in Saranac, upstate New York.

By that time both artists enjoyed established reputations. Having achieved recognition as a children’s author with Treasure Island (1883) and A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885), Stevenson had ascended to international celebrity with the publication of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886; fig. 4), which was performed on the Broadway stage that year. While the writer explored the dark side of human nature, the sculptor gave form to its brighter aspects. Beginning with the monument to Admiral David Glasgow Farragut (1881; fig. 5), public sculptures honoring Civil War heroes showed Saint-Gaudens’s power to make realistic detail serve the expression of ideals. Low, a respected mural painter, never achieved the artistic stature of Stevenson and Saint-Gaudens, yet the three remained bound by mutual ambitions and youthful recollections. By bringing his friends together, he set the stage for the creation of an enduring portrait.

Friendship

Low correctly anticipated that the two artists “should like each other,” despite their contrasting temperaments.[16] Reiterating Low’s first impression, Stevenson described the sculptor as “a splendid straightforward and simple fellow . . . and handsome as well.”[17] Saint-Gaudens viewed the writer as “astonishingly young, not a bit like an invalid, and a bully fellow.”[18] This perception attests to Stevenson’s personal magnetism more than his physical condition. Four months earlier, he had almost died of hemorrhages suffered after returning to Edinburgh for his father’s funeral, and within days after arriving in the US he was again desperately ill. Despite the fragility of Stevenson’s health, Saint-Gaudens persuaded him to accept his offer of a portrait during the weeks he spent in New York. The combination of words and image that resulted bespeaks bonds of friendship and a shared commitment to a creative life.

While Saint-Gaudens’s time with Stevenson was brief, it left a lasting impact on his life and work. The sculptor brought clay and easel to the writer’s hotel rooms and modeled his subject from life as he sat propped up in bed. The sittings, which Low attended whenever possible, were animated by lively conversation on a variety of subjects. Five sessions of two to three hours each enabled Saint-Gaudens to complete his initial goal: a model of the head in profile. After Stevenson’s departure for the Adirondacks, Saint-Gaudens enlarged his concept of the portrait. In May the two men met once more near Low’s summer home in Manasquan, New Jersey; on this occasion the sculptor made a drawing and casts of the writer’s hands.[19] Rhapsodizing about their time together, Saint-Gaudens wrote to Low, “My episode with Stevenson has been one of the events of my life, . . . I am in [a] beatific state.”[20] A small sketch shows a caricatured Saint-Gaudens kneeling before the writer’s haloed profile—the view his sculpture would immortalize (fig. 6).

To represent Stevenson, Saint-Gaudens used the bas-relief technique that he favored for portraits of artist-friends. He began to create such works in Paris in the late 1870s. These early bronzes show the figure’s head in profile accompanied by an inscription and sometimes a symbol or attribute.[21] Most of the subjects—all but one a painter—were men with whom he shared studio space and/or affiliation in the Society of American Artists and/or the Tile Club. Saint-Gaudens’s tokens of affection attracted public interest when the sitter was a celebrity. A cast of Jules Bastien-Lepage (fig. 7) was the first of the sculptor’s works to be purchased by a museum (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). In exchange for the bronze, the French artist painted a portrait of Saint-Gaudens.[22] Back in New York in the late 1880s, the sculptor traded works of art with William Merritt Chase, who offered him a painting as payment for a large relief (fig. 8).[23] He also exchanged portraits with Kenyon Cox, whose portrait of Saint-Gaudens showed him in his studio working on the Chase relief (fig. 2).[24]

Saint-Gaudens’s relationship with Stevenson began when the writer agreed to sit for him, but it left a lasting impression on his life and work. The image that resulted is the most iconographically complex and psychologically penetrating of his representations of artist-friends. While allowing the two men to get to know each other, the process of modeling Stevenson’s likeness deepened Saint-Gaudens’s concept of the art of portraiture. The sculptor’s son, Homer, explained, “Hitherto . . . his sitters had never consciously been anything but visible, tangible objects to interpret. . . . But after each visit [with Stevenson] there grew . . . a desire to comprehend the mental significance of the man before him and to bring it to light through his physical expression and gesture.”[25] The representational choices Saint-Gaudens made about Stevenson’s body illuminated his subject’s inner life.

Saint-Gaudens’s first version of the portrait acknowledges Stevenson’s invalid condition, honors his literary achievement, and celebrates a three-way friendship (fig. 9). The writer’s bed, in which he sits propped up on pillows, extends across the lower half of the horizontal composition. Verses of a Stevenson poem fill the upper field, punctuated by the winged horse Pegasus. This classical motif, seen also in Saint-Gaudens’s Chase portrait (fig. 8), symbolizes fame. At the top of the relief, an ivy border with berries provides a decorative frame. According to Low the vine functioned as an emblem of the friendship in which the work originated.[26] The dedication, “To Robert Louis Stevenson from his friend Augustus Saint-Gaudens,” underscores the sculptor’s inclusion in this relationship.

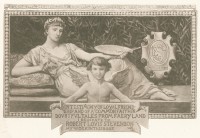

The poem toward which Stevenson gazes and gestures completes the iconography of friendship. Titled “To Will. H. Low,” it was Stevenson’s response to Low’s dedicating to him the illustrations to John Keats’s “Lamia,” an 1885 book project on which Saint-Gaudens had provided advice (fig. 10). Saint-Gaudens’s portrait of Stevenson resembles Low’s dedication in horizontal format, reclining figure, and combination of words and image. Low dedicated his work to Stevenson, “In testimony of loyal friendship and of a common faith in doubtful tales from faery land.” Above a female allegory of painting is a Latin quotation from Cicero that translates as, “There is no more sure tie between friends than when they are united in their objects and wishes.”[27] Stevenson published “To Will. H. Low” in Underwoods in 1887, the same year he sat for Saint-Gaudens. He gave the sculptor an advance copy with an inscription recognizing affinity in their respective media: “Each of us has his own way / I with ink and you with clay.”[28]

“Lamia,” Keats’s retelling of a young philosopher’s seduction by a serpent disguised as a beautiful woman, spoke to the aesthetic calling of Stevenson, Saint-Gaudens, and Low (fig. 11). Beginning with the line, “Youth now flees on feathered foot,” Stevenson’s poem to Low describes a similarly consuming passion for beauty that culminates in death rather than attainment (see Appendix). Having described beauty’s allure and elusiveness, he writes in the third stanza,

In wet wood and miry lane

Still we pound and pant in vain;

Still with leaden foot we chase

Waning pinion, fainting face;

Still, with gray hair we stumble on

Till, behold, the vision gone!

Where hath fleeting beauty led?

To the doorway of the dead.

While the pursuit of beauty destroys Keats’s protagonist, in Stevenson’s view it gives meaning to life. The poem concludes, “Life is over, life was gay. / We have come the primrose way.” Stevenson sent the poem to Low with a letter affirming this conviction and the mutuality of their aim. “I have copied out on the other sheet some verses, which somehow your pictures suggested: as a kind of image of things that I pursue and cannot reach, and that you seem—no, not to have reached, but to have come a thought closer to than I. This is the life we have chosen; well, the choice was mad, but I should make it again.”[29] Death thwarts fulfillment, but it does not deprive the artistic life of joy.

In a second, circular version of the portrait Saint-Gaudens placed more emphasis on Stevenson’s credo (fig. 1). Eliminating the Pegasus symbol and half of the bed, he drew closer to the writer and his verses. The medallion format—recalling Renaissance medals—strengthens the connection between the two. Stevenson’s physical frailty is apparent in the sunken body, slender arm, and delicate fingers that hold his trademark cigarette. Directing attention to the poem, the more deeply contoured and finished head and hand reference the exuberance with which he overrode regrets about life’s transience.

Alexis Boylan has posited that Saint-Gaudens’s portrayal of Stevenson as an invalid “satisfied his own affective desires for male intimacy while simultaneously reinforcing stark visual and cultural markers of abledness and disabledness.”[30] She rightly views the bas-relief as an intimate counterpoint to the sculptor’s monumental work. Boylan makes much of the decision to represent the writer as bedridden when he was fully, and sometimes frenetically ambulatory, as John Singer Sargent’s 1887 painting of him and Fanny shows (fig. 12). In her reading, an implicitly healthy Saint-Gaudens assumes the role of protector and attendant by representing as Stevenson as “stuck in bed.”[31]

Yet bed was far more than a locus of physical confinement for Stevenson. As a gateway to the imagination, it was the site of his creativity. In “The Land of Counterpane,” the writer recalled how, as a sick child, he had waged wars, sailed oceans, and built cities within the sheets and blankets. When he grew to be a man, bed became a stage on which Stevenson ate, smoked, read, entertained—and produced much of his finest writing. In Saint-Gaudens’s portrait, words and image together convey the dedication to a creative calling that Stevenson shared with his two artist-friends.

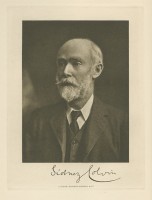

Stevenson and his family departed for the South Pacific in June 1888 without seeing Saint-Gaudens’s finished portrait, but after they had settled in Samoa, he commissioned two thirty-six-inch bronze reproductions of the medallion. One was for himself, the other for his close friend Sidney Colvin, keeper of prints and drawings at the British Museum (fig. 13). Expressing his appreciation, Colvin wrote to Saint-Gaudens, “Technically the work seems to me one of the greatest interest, and as a likeness it is far the best that exists.”[32] The sculptor also gave Low a plaster cast, which the painter installed over the fireplace in his studio (fig. 14). In Stevenson’s absence, Saint-Gaudens’s portrait maintained his presence in the homes of friends on both sides of the Atlantic.

When Stevenson’s bronze arrived at Vailima, his island villa, he placed it over his smoking-room fireplace and reported that he viewed it as a “speaking likeness.”[33] He addressed Saint-Gaudens as “God-like sculptor,” an epithet derived from an Emerson poem that Low had quoted in conversation with his two friends.[34] Although the writer continued to correspond with Saint-Gaudens from Samoa and sent regards in letters to mutual friends, they never met face to face again. On December 3, 1894, Stevenson was helping his wife prepare a salad when he suddenly grabbed his head, cried out, “Do I look strange?” and fell over backward.[35] Two hours later, at age forty-four, he died of a cerebral hemorrhage and the world saw Saint-Gaudens’s souvenir of friendship with new eyes.

Celebrity

In the wake of Stevenson’s death, Saint-Gaudens’s medallion portrait became an icon of the writer’s celebrity in the US. Beginning in 1895, the image received increased circulation through illustrated magazines and reduced reproductions. Spearheading this expansion was Richard Watson Gilder, intimate friend of Saint-Gaudens and influential editor of Century Magazine from 1881 to 1909.[36] Gilder promoted Stevenson and Saint-Gaudens simultaneously to a wider audience, increasing their fame by association. Saint-Gaudens capitalized on this process by creating replicas of the life portrait that eventually made their way into public institutions.

With his wife, Helena de Kay, Gilder stood at the center of New York’s genteel elite (fig. 15). Upon assuming the helm at Century, he turned what had begun as an evangelical publication into an instrument for elevating culture and advocating reform. Art played an important role in Gilder’s editorial project; in his mind good morals were related to good taste. He sought to counter a rising tide of materialism by promulgating ideals of beauty, imagination, and patriotism.[37]

Saint-Gaudens was Gilder’s ally in this cultural campaign. Both men adhered to traditional standards while seeking to invigorate the art of their own time. Gilder would say that Saint-Gaudens’s “wrath” at the National Academy’s rejection of his work had precipitated the founding of the Society of American Artists at the editor’s home in 1877.[38] This breakaway group of “new men,” shaped by European art and training, was dedicated to principles of individual expression and sound technique. When Gilder began publishing articles on and reproductions of art in Century, Saint-Gaudens’s sculptures received individual attention and high praise. While focusing on the Civil War monuments (he had posed for the legs of Farragut), Gilder also called attention to the bas-relief of Stevenson.

As Century’s editor, Gilder believed in an “America first” policy, but he became interested in Stevenson early in his career.[39] He learned of the Scotsman’s work through Edmund Gosse, Century’s English agent and a member of the writer’s London circle. On February 17, 1883, Gilder wrote a letter presenting himself to Stevenson and noting that they had “common friends.” He expressed enthusiasm for the “human and artistic charm and force” of Stevenson’s books and asked to see some of his “handwriting—especially of the fictitious sort—with a view to publication in the magazine.”[40] To bolster his appeal, Gilder had published a favorable review of The New Arabian Nights—the book that had electrified Saint-Gaudens—a few weeks earlier in Century.[41] Stevenson sent a clipping to his parents, reporting gleefully, “In eighteen hundred and eighty-three, / America discovered me!”[42] When the author arrived in New York on September 7, 1887, he was greeted by Low and a throng of admirers. “My reception here was idiotic,” he told Colvin. “If Jesus Christ came, they would make less fuss.”[43] In the ensuing years, Gilder continued to advance Stevenson’s US celebrity through publication and criticism of his work.

After the writer’s death in 1894, Century also featured reproductions of Saint-Gaudens’s medallion portrait, captioned as “modeled . . . during Stevenson’s illness in New York.” It first appeared in November 1895 as a full-page illustration to an article titled “Robert Louis Stevenson, and His Writing” (fig. 16). The author was the esteemed art and architectural critic Mariana Griswold van Rensselaer, a close friend of Gilder whose portrait Saint-Gaudens had sculpted in 1888 (fig. 17). Van Rensselaer opened by stating, “No other writer of our time has come as near as Stevenson to the conquest of a perfect English style.” After describing the meticulous process by which the Scottish writer had made himself a master craftsman, she shifted attention to the “strong and charming personality” that “inspire[d] . . . infuse[d] . . . and to a great degree create[d]” his work.[44]

In Van Rensselaer’s eyes, Stevenson’s mental aliveness—his exuberance—overshadowed his physical infirmity, a point borne out in Saint-Gaudens’s portrait. Recounting her 1888 meeting with the writer, in the company of Low and Saint-Gaudens, she wrote, “His body was in evil case, but his spirit was more bright, more eager, more ardently and healthily alive than that of any other mortal.” Van Rensselaer ascribed Stevenson’s charm to the fact that “he assumed you too were alertly alive; he believed that you would understand and share his interest in all interesting things.”[45] Saint-Gaudens’s “speaking likeness” captures Stevenson’s ability to engage visitors in lively conversation from his bed. In photographic reproduction, this aspect of the portrait comes to the foreground. The writer’s personality overshadows his words.

Gilder’s reproduction of the Stevenson medallion in Century gave the work artistic as well as literary significance. An 1897 essay on Saint-Gaudens by art critic William A. Coffin, published in conjunction with Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s history of the Shaw Memorial, featured a three-quarter-page illustration (fig. 18). Among the portraits in bas-relief, Coffin singled out the Stevenson as exemplifying Saint-Gaudens’s talent. He wrote, “The wistful but energetic profile . . . is sufficient to show how well the sculptor understands the portrayal of character and expression.”[46] As an icon of literary celebrity and a work of art by a master sculptor, the portrait thus acquired dual value.

Though Saint-Gaudens modeled Stevenson for personal pleasure, he also saw commercial potential in a portrait of an international celebrity. In 1889, he sent the finished plaster to the National Academy of Design, where it attracted critical attention but mixed reviews.[47] Art Amateur objected to the representation of Stevenson as an invalid,[48] while the New York Sun praised the realism of the bedridden pose.[49] A number of art writers complained about the length of the inscription. Between the National Academy exhibition and Gilder’s publication of the medallion, the market for reproductions was slow to develop.

Literary admirers of Stevenson were the first to appreciate Saint-Gaudens’s synthesis of words and image. In 1890, George Allison Armour, a book collector from Chicago, commissioned a thirty-six-inch bronze medallion, one of four cast in the writer’s lifetime (fig. 1). Armour never met Stevenson, but letters from their mutual friend Edmund Gosse attest to his abiding interest in the writer’s life and work. After saying farewell to Stevenson on the eve of his departure for the US, Gosse wrote immediately to Armour describing his friend’s state of mind. “He prowled about the room, in his usual noiseless panther fashion, talking all the time, full of wit and feeling and sweetness, as charming as ever he was, but with a little more sadness and sense of crisis than usual.”[50] When Stevenson had settled in Samoa, Gosse solicited the book collector’s opinion of his Polynesian writings.[51]

Saint-Gaudens’s close attention to detail informs every aspect of Armour’s bronze. The poem to Low sweeps gracefully around the figure in the top left quadrant, while the dedication, “To Robert Louis Stevenson in his Thirty Seventh Year, Augustus Saint-Gaudens,” runs along the ivy border on the right. The ball finial on the bedpost rhymes with this curvilinear arrangement of the text. At the bottom of the circle, another inscription identifies the replica as made for Armour. New York architect and decorator Stanford White, who collaborated with Saint-Gaudens on his most celebrated public monuments, designed the elaborately hand-carved octagonal frame.

In subsequent casts of the medallion, Saint-Gaudens continued to refine the composition. He divided the poem into blocks and placed the dedication on opposite sides of the first stanza. Stevenson’s relief is inscribed, “To Robert Louis Stevenson” (left), “From Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1888” (right); the one made for Colvin, “To Sidney Colvin” (left), “Robert Louis Stevenson” (right; fig. 13).[52] Saint-Gaudens squared off the bedpost in these later replicas, presumably to accord with the geometric arrangement of the text. The last of the large bronzes was made for Benjamin Cable, whose interest in Stevenson and Saint-Gaudens remains unclear. As a director of the Rock Island Railroad and one-time congressman from Illinois, he may have crossed paths with Armour in Chicago. Cable’s name does not appear on his medallion; the dedication is the same as Stevenson’s, but with a date of 1887 in Roman numerals below the verses.[53] Copyrighted in 1894, it anticipates the spate of casts that would soon issue forth from Saint-Gaudens’s studio.

After Stevenson’s death that December and concurrent with Van Rensselaer’s article in Century the following year, Saint-Gaudens began to produce reduced, affordable medallions, eighteen and twelve inches in diameter. In so doing, he capitalized on the writer’s celebrity and the increased value of an image made from life. Reproductions were initially sold, framed or unframed, in New York through Tiffany and Company and in Boston through Doll and Richards; soon other galleries, such as Wunderlich, became involved.[54] With a few exceptions, these casts lacked personal dedications; they were inscribed simply “To Robert Louis Stevenson . . . Augustus Saint-Gaudens.” The sculptor did, however, sometimes vary the drapery and patina to give a replica a degree of originality. By making such changes, Saint-Gaudens sought to satisfy the desire of some buyers for limited editions. In 1902, he began to issue reproductions of the first, rectangular portrait in both bronze and gilded copper electrotype. In these different formats, the Stevenson sculpture was the most popular of Saint-Gaudens’s bas-reliefs.

The making of multiples became a welcome source of income for Saint-Gaudens, whose payment for monumental work was sporadic at best. By the end of the century he was running a successful business in small bronze reproductions.[55] In 1899, Saint-Gaudens wrote to his brother, Louis, “I have quite a little income now from the Stevensons and the Diana. . . . It seems that bronzes sell very little at first and then when they commence the sale goes on increasing if the work is attractive. People see the bronze in friends’ homes and that suggests their purchase to them.”[56] As the demand for reproductions increased, the sculptor used copyright as a means of guaranteeing quality and insuring against image piracy. His wife, Augusta, gradually took over management responsibilities; as keeper of her husband’s flame and holder of the copyrights, she continued to market reproductions between his death in 1907 and her own in 1926. Saint-Gaudens’s widow expanded the list of small bronze offerings beyond the original Stevenson, Diana, Amor Caritas, and Puritan. She was particularly successful in selling casts to notable museums.[57]

The number of Stevenson reductions sold in Saint-Gaudens’s lifetime and estate-authorized casts is uncertain, and their provenances can be difficult to trace. One notable exception is the eighteen-inch relief in the Bowdoin College Museum of Art (fig. 19), which came with a bequest from Mary Sophia Walker in 1904. Walker (fig. 20), with her sister, Harriet Sarah Walker, gave Bowdoin its elegant Walker Art Building in 1894 (fig. 21). One of America’s earliest college museum buildings, this small gem of the American Renaissance was designed by New York architect and Saint-Gaudens’s close friend Charles Follen McKim, the subject of one of his earliest artist portraits (fig. 22).[58] When Walker began buying art for Bowdoin’s museum, McKim may have encouraged her to acquire a Stevenson medallion in a square oak frame with mitered corners, bronze rosettes, and beaded edge. McKim would have appreciated the personal content of the portrait. Saint-Gaudens’s caricature commemorating a trip the two men took with Stanford White through southern France in 1878 anticipates the Stevenson relief as a souvenir of friendship (fig. 23).

Members of Saint-Gaudens’s family may also have sparked Walker’s interest in his portrait of Stevenson. The sculptor’s favorite niece, Rose Standish Nichols, lived just blocks away from her on Boston’s Beacon Hill. Nichols owned a unique eighteen-inch medallion with a personal dedication (Nichols House Museum). She also acted as a sales liaison to galleries and private collectors. However Walker learned of the Stevenson bas-relief, Saint-Gaudens’s debt to Renaissance art—which accorded with McKim’s design of her museum building—and the celebrity of both writer and sculptor would have contributed to the sculpture’s appeal.

The Walker bequest of art to Bowdoin (fig. 24) anticipates the institutional value the Stevenson portrait gained in the twentieth century. Today reproductions of the work can be seen at numerous colleges and universities. Some (Harvard, Yale, and Princeton) came as part of rare book collections, others (Amherst and Dartmouth) were acquired by libraries and subsequently transferred to art museums, and still others (Peter and Paula Lunder’s recent gift to Colby) were given directly to the latter. Municipal art museums, too, added replicas to their collections through gifts, bequests, and purchases (Art Institute of Chicago, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). In these educational settings, an icon of celebrity became a stimulus to art study and appreciation.

Memory

While Saint-Gaudens’s medallion circulated through reproduction in the US, in the writer’s native Scotland it became the basis for a singular commemorative tribute. On December 10, 1896, two years after the writer’s death, a crowd of family, friends, and admirers packed the Music Hall in Edinburgh, where they paid homage to their native son and endorsed a resolution to erect a national memorial. Former British Prime Minister Lord Rosebery, who chaired the meeting, presented the proposal by appealing to Scottish pride. “I do not . . . wish,” he declared, “to belong to a generation of which it shall be said that they had this consummate being living and dying among them, and did not recognise his splendor and his merit.”[59] Saint-Gaudens’s portrait had captured Stevenson’s exuberant personality; in creating a memorial the sculptor was paying homage to the Scotsman’s art and character.

Though an aura of romance had surrounded Stevenson’s global peregrinations, his countrymen lamented the fact that he had not been laid to rest in Scottish soil. Instead, Tusitala—in Samoan, the “teller of tales”—was buried on Mount Vaea, looking down over his Vailima home. A plaque on his tomb contains the short poem “Requiem,” which he had written in 1880 at a time when death seemed imminent. It reads:

Under the wide and starry sky,

Dig the grave and let me lie;

Glad did I live and gladly die.

And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you ’grave for me:

Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

Epitomizing Stevenson’s affirmative embrace of life and death, this epitaph would reappear on the Edinburgh memorial.

Lord Rosebery conceived the commemorative project, but it was Sidney Colvin who shepherded it to completion (fig. 25). For twenty years, Colvin had been a steadfast supporter of Stevenson’s literary ambition. Of their first meeting in 1873, Colvin wrote, “To know him was to recognize at once that here was a young genius of whom great things might be expected.”[60] After Stevenson’s death, Colvin became his literary executor and collaborated with Charles Baxter on the Edinburgh edition of his collected writings. Colvin treasured the cast of Saint-Gaudens’s medallion that Stevenson had commissioned for him and gave it public visibility. He exhibited it at London’s New Gallery in 1894 and reproduced it as a frontispiece to the poetry volume of the Edinburgh edition in 1897. Based on his admiration for the portrait, Colvin promoted Saint-Gaudens for the memorial commission and served as liaison between the American sculptor and his Scottish patrons.[61]

An executive committee formed to solicit funds and oversee the design of the memorial approached Saint-Gaudens about the project in 1898. By this time, they had received contributions from admirers in the UK, the US, and the British colonies, but not enough to realize their original vision of an outdoor structure.[62] As an alternative, the committee went to St. Giles’ Cathedral (fig. 26), Edinburgh’s Presbyterian high kirk, with a proposal for a wall decoration. Though Stevenson had long ago forsaken church and country, he would join nobles, clergy, soldiers, and politicians in this pantheon of Scottish worthies.

The choice of Saint-Gaudens was an ideal one given the proposed form and content of the memorial. He was the only artist of international distinction who had modeled Stevenson from life.[63] The committee believed that the sculptor’s close friendship with the writer would guarantee, in Colvin’s words, a work of “love and deep sympathy,” and in this they were correct.[64] Taking the 1888 portrait as his starting point, Saint-Gaudens labored long and hard on a monumental bronze relief for Saint Giles’s western wall (fig. 27). Changes made to the original portrait reflect the commemorative character of the project, the influence of the committee, and Saint-Gaudens’s own evolving sense of the significance of his subject’s art and life. To Stevenson’s cousin and first biographer, Graham Balfour, he wrote in 1902, “The Memorial for Edinboro’ is more than a reproduction. It is a very considerable enlargement and development of the original relief.”[65] When the work was completed, the sculptor told Colvin, “I have expressed myself in this memorial to our friend to the fullest of my ability.”[66]

Surviving drawings and letters show the process by which Saint-Gaudens transformed the life portrait into a memorial. His initial conception consisted of a vertical variation on the medallion, still inscribed with the poem to Low but exchanging the ivy of friendship for the laurel of victory (fig. 28). Woven into the garland, Scottish heather and Samoa hibiscus symbolize the writer’s birth and death places. In January 1899, Saint-Gaudens traveled from Paris to London and Edinburgh to meet with members of the memorial committee and see the proposed site. Writing to his niece, Rose Nichols, he described an altered vision: “I shall probably make the Stevenson full length, with a pen in his hand instead of the cigarette, in gilded bronze, with perhaps the name of his works or some selections from his writings that they may select” (fig. 29).[67] Back in France, Saint-Gaudens revised his concept once again. In another letter to Nichols, he imagined “just a great slab with Stevenson in bronze, life-size, seated probably in a chair with a great blanket over his legs” (fig. 30).[68] The first version of the memorial constitutes a synthesis of these last two schemes (fig. 31).

Stevenson appears here as an artist more than an invalid. Returning to the full-length horizontal format, the sculptor replaced the bed with a couch, reduced the number of pillows from three to two, and exchanged the bedclothes for a traveling rug. By eliminating the cigarette, he used attribute to define his subject’s occupation. With pen and paper in hand, Stevenson appears not conversational but in the process of creation. Colvin recalled, “To me, that figure, propped by pillows, with head always quite unsupported and erect, sitting with the scroll of paper in its hand, is a reminiscence of many days and scenes. Oftentimes I have so seen him . . . invalided, but indefatigably working.”[69] By stepping back from his subject and highlighting creativity rather than infirmity, Saint-Gaudens made Stevenson, the dead writer, appear forever living.

While the sculptor focused on the figure for the memorial, the committee took charge of the inscription. Allegedly in deference to the religious context, they replaced the poem to Low with excerpts from a prayer titled “For Success” that Stevenson had composed for the Sunday services he conducted at Vailima. Other selections from his writings included “Requiem” and an excerpt from a second poem, “Bright is the Ring of Words” from Songs of Travel (1895), which speaks of art’s power to survive its maker’s death. The committee also composed a dedication that, in its final iteration, reads: “This memorial was erected in his honour by readers in all quarters of the world who admire him as a master of English and Scottish letters, and to whom his constancy under infirmity and suffering, and his spirit of mirth, courage, and love, have endeared his name.” The inscription thus paid tribute to Stevenson as both a writer and a man.

Between November 1899 and May 1900, Saint-Gaudens corresponded with Colvin about the content, length, and placement of the verbal elements. These letters reveal the challenge the project presented of balancing textual desiderata with available space. In the first version of the memorial, the prayer followed by “Requiem” and bordered by three shells fills the entire field around the figure. The dedication and the second poem appear together on the plinth. Visually and conceptually the four-part inscription produced a cluttered composition (fig. 31). Upon seeing the work in bronze, Saint-Gaudens wrote to Colvin on November 10, 1900, that he was dissatisfied with the patina and was going to have the casting done again. He reported that he had decided on some changes that would “improve” the work and mentioned specifically clearing the space around the sitter’s head.[70]

To achieve the compositional clarity he desired, the sculptor consolidated the memorial’s content. Leaving the prayer to stand alone in the main panel, he moved “Requiem” to the plinth below the dedication and omitted the second poem altogether (fig. 32). By eliminating decorative details of shells and sloping swan’s neck couch back, Saint-Gaudens, as he had in the medallion, strengthened the focus on the writer and the central text. The figure represents Stevenson’s achievement as an artist, the prayer, his aspirations as a man. It petitions:

Give us grace and strength to forbear and to persevere. Give us courage and gaiety and the quiet mind. Spare to us our friends, soften to us our enemies. Bless us, if it may be, in all our innocent endeavours. If it may not, give us the strength to encounter that which is to come, that we may be brave in peril, constant in tribulation, temperate in wrath, and in all changes of fortune, and down to the gates of death, loyal and loving to one another.

This expression of humility and humanity articulates a moral philosophy that Stevenson’s life exemplified.

Saint-Gaudens could not attend the memorial dedication on June 28, 1904, but in the weeks that followed he received numerous letters of thanks and praise. W. B. Blaikie, whose firm had printed the Edinburgh edition, reported, “You can’t think how delighted everybody, whose opinion is worth having, is with the memorial. Nothing could be more beautiful, more refined, more distinguished.”[71] A total stranger, Henry Johnstone, expressed appreciation for the sculptor’s “noble work.”[72] Colvin extolled the sculpture’s form and content saying, “You have improved enormously on your original circular design, and produced a truly beautiful and satisfying result.”[73] Passing through Edinburgh a few weeks later, Charles McKim sent congratulations to Saint-Gaudens “on the great achievement of your labor of love for R. L. S.” Stressing the significance of the prayer, he continued, “I was much impressed and moved by it as a work of sculpture into which the great inscription had been worked, as a wonderful . . . part of the whole composition. You can rely on that effort and die on it, my boy, though you should never put your hand to the wheel again.”[74]

McKim’s words allude poignantly to the personal significance that the Stevenson memorial had acquired for Saint-Gaudens. While working on the composition, the sculptor, age fifty-two, was diagnosed with rectal cancer. Advised to return immediately to the US for surgery, he underwent two major operations in July and November of 1900 and settled year-round in Cornish, New Hampshire. Saint-Gaudens eventually regained enough strength to return to his studio and to finish the Edinburgh project, but time was running out. Like Stevenson, he had come to know artistic fame tempered by mortal finitude.

Saint-Gaudens drew inspiration from Stevenson as he struggled unsuccessfully against terminal illness. Even before the cancer diagnosis he had invoked his friend’s philosophy during a period of deep depression. “The principal thought in my life,” he wrote in September 1898, “is that we are on a planet going no one knows where, . . . that . . . the passage is terribly sad and tragic, and . . . the practice of love, charity, and courage are the great things.”[75] In a March 1900 letter of sympathy to Helen Farnsworth Mears, a former student, Saint-Gaudens referred her to Stevenson’s prayer. “It is a great thing,” he told her. “If you can get it into your heart and mind it would be a blessing and in some measure a consolation.”[76] Though Low claimed Saint-Gaudens regretted the committee’s decision to replace the original poem, by the time of the memorial’s completion, the prayer helped the sculptor face his fate.[77]

After Saint-Gaudens’s death at fifty-nine on August 3, 1907, mourners repeatedly connected him to Stevenson. At the sculptor’s funeral, the minister opened the service with the prayer inscribed on the Edinburgh memorial.[78] Gilder’s magazine, Century, published a posthumous tribute that noted, “There was a peculiar sympathy between Saint-Gaudens and his friend Robert Louis Stevenson, and in more ways than one were their fates, toward the last, similar.”[79] Upon receiving the news in Edinburgh, Charles McKim went to St. Giles’ Cathedral and stood before his late friend’s testament to art’s power to redeem life’s suffering. “It was,” McKim recalled, “the nearest I could come to him.”[80] To those who understood their shared ideals and struggles Saint-Gaudens’s public memorial to Stevenson offered private consolation.

Legacy

Even before his death Saint-Gaudens regarded the Stevenson portrait as a distinctive part of his artistic legacy. Beginning in 1898, the sculptor gave eighteen-inch medallions to family members, friends, and colleagues who would have appreciated the aesthetic value of the work and his personal identification with the sitter. The latter included studio assistants such as Mary Lawrence (fig. 33) and Henry Hering, who had worked on the memorial, and art critic Coffin, who had praised the portrait in Century. Coffin subsequently organized the art section of the 1901 Pan-American Exposition, where a plaster cast of the Stevenson Memorial was prominently displayed. The following Christmas, Saint-Gaudens presented him with a second Stevenson portrait, a bronze of the first, horizontal version with a personal dedication.[81] To reinforce memory of his friendship with her stepfather, Saint-Gaudens also sent a medallion portrait to Belle Osbourne (then Isobel Strong), who was effusive in her appreciation. “I have longed for one ever since I left home where I was always used to seeing it over the fireplace. I have seen it in many parts of the world too and in the possession of people who were strangers to me and I have always longed to have a medallion of my very own to keep.” Strong closed by saying, “I have nothing left to ask for.”[82]

Self-consciously linking himself to Stevenson in his waning years, Saint-Gaudens also gave form to a shared belief: that the work they created would live on.[83] A reduced variation on the first memorial design (fig. 34), offered for sale in 1902, unites the figure of the writer with the excerpt from Songs of Travel that the sculptor had cut from the original inscription. The poem reads:

Bright is the ring of words

When the right man rings them.

Fair the fall of songs

When the singer sings them.

Still, they are carolled and said—

On wings they are carried—

After the singer is dead

And the maker buried.

Ten bronze casts exist of this relief, one of which Saint-Gaudens made for longtime friend and Cornish, New Hampshire, neighbor Maria Oakey Dewing in 1905. Delighted with the work, which she had hitherto seen only in plaster, the painter wrote, “The Stevenson is superb in bronze and my name placed by yr [sic] own in that finely modeled background pleased me greatly.”[84] In what was, in effect, a parting gift, Saint-Gaudens affirmed the bonds of artistic friendship and the enduring resonance of art.

For other artists touched by the sculptor’s achievements, the Stevenson memorial provided an exemplar for new work. In 1906, composer and musician Edward MacDowell’s wife, Marian, wrote to Saint-Gaudens asking him to make a bas-relief of her dying husband.[85] Saint-Gaudens was too ill to accept the commission but he passed it on to Helen Mears, the former student to whom he had recommended the Vailima prayer. Taking the Edinburgh relief as her model, Mears showed MacDowell in profile, seated against a pillow and covered by a blanket (fig. 35). The inscription—bars from the third movement of his Sonata Tragica for piano and a line from one of his poems, “Night Has Fallen on a Day of Deeds”—conveys the theme of impending death.[86] In this commemorative image, Mears paid simultaneous tribute to her subject and her teacher.

Ellen Emmet Rand’s late painting of Saint-Gaudens also invites comparison with his reliefs of Stevenson (fig. 36).[87] Executed after a fire in the Cornish studio had destroyed Kenyon Cox’s early portrait of him at work (fig. 2), it shows the sculptor in a contemplative attitude.[88] In asking Saint-Gaudens to pose for her, the young and ambitious Rand was likely seeking to enhance her reputation by association. His acceptance, as he faced the end of life, suggests his desire for a definitive image to replace what he had lost. No record exists of what transpired in the sittings that took place in January 1905. Rand may have referred to a 1904 series of photographs by DeWitt Ward in which the sculptor wears the same tweed suit, but it is equally plausible that Saint-Gaudens helped to shape the final composition. The combination of profile head and raised hand formally mirrors his portrait of and memorial to Stevenson and, iconographically, the latter’s representation of creativity. Stevenson’s attribute is a pen and Saint-Gaudens’s glasses, in keeping with the visual character his art. The writer’s poised quill and the sculptor’s lowered eyes bespeak the internal, imaginative aspect of their respective processes.

Whether or not Rand was interested in linking Saint-Gaudens to Stevenson, the memorial exhibition mounted at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1908 provided ample opportunity to do so. In addition to Rand’s portrait, the show included thirty-six-inch and eighteen-inch Stevenson medallions and a plaster cast of the Edinburgh memorial.[89] Gilder and McKim, both members of the exhibition committee, would certainly have seen significance in the resemblance, and this may have influenced their promotion of Rand’s painting. Gilder reproduced the work in Century in October 1907 and, after the exhibition closed, McKim spearheaded a successful campaign to purchase it for the Metropolitan’s collection. Under the auspices of the Saint-Gaudens Memorial Committee, the museum subsequently acquired an estate-authorized cast of the thirty-six-inch medallion, establishing it as a signature work. While the Stevenson portrait embodied memories of camaraderie and aspiration, the memorial bespoke courage and achievement. Elements of friendship, celebrity, and memory that had shaped the evolution of the sculpture made it Saint-Gaudens’s most familiar and fitting legacy.

Conclusion

When Augustus Saint-Gaudens conceived his profile portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson, he could not have anticipated the personal and artistic significance it would acquire. Made in celebration of an artistic friendship, the work provided in the ensuing years a stream of income, a source of consolation, and a way to bid adieu to a creative life. Each iteration of the sculpture reflected Saint-Gaudens’s unflagging effort to achieve perfection. Bronze, in his eyes, was “eternal,” a medium “to be looked upon very probably for centuries.”[90] Even after a work was completed, the sculptor confessed to seeing “so much that could have been bettered.”[91] Faced with what he called “the great and awful mystery of death,”[92] Saint-Gaudens persevered, as had Stevenson, in the pursuit of beauty.

Over a period of fifteen years, Saint-Gaudens developed and deepened his representation of Stevenson. Using attribute, setting, and symbolism, he captured first the invalid’s exuberant personality and, second, the writer’s dedication to his work. Stevenson’s words form an integral part of Saint-Gaudens’s sculptures. Conjoined with the different images, they express creative calling, moral aspiration, and faith in art’s longevity. Each new variation on the original composition further demonstrated Saint-Gaudens’s “desire to comprehend the mental significance” of Stevenson.[93] Together they comprise a composite portrait of an artist who had “lighted up one whole side of the globe.”[94]

From the beginning, viewers of Saint-Gaudens’s bas-reliefs of Stevenson have owed their experience to a transatlantic network of interested and influential friends. Low’s introduction, Gilder’s publication, and Colvin’s commission laid the groundwork for the creation of the portrait and its proliferation. Over time, changes in form, inscription, and context altered the content of the image and expanded audience interaction far beyond the artists’ intimate circles. As death brought Stevenson and Saint-Gaudens closer in the eyes of those who knew them personally, they moved together, in sculpture, into the public realm. In museums, libraries, schools, and a cathedral, the portrait and its variations continue to invite reflection on their common theme: the transience of life and the timelessness of art.

“To Will. H. Low”

Robert Louis Stevenson

Youth now flees on feathered foot.

Faint and fainter sounds the flute,

Rarer songs of gods; and still

Somewhere on the sunny hill,

Or along the winding stream,

Through the willows, flits a dream;

Flits but shows a smiling face,

Flees but with so quaint a grace,

None can choose to stay at home,

All must follow, all must roam.

This is unborn beauty: she

Now in air floats high and free,

Takes the sun and breaks the blue;—

Late with stooping pinion flew

Raking hedgerow trees, and wet

Her wing in silver streams, and set

Shining foot on temple roof:

Now again she flies aloof,

Coasting mountain clouds and kiss’t

By the evening’s amethyst.

In wet wood and miry lane,

Still we pant and pound in vain;

Still with leaden foot we chase

Waning pinion, fainting face;

Still with grey hair we stumble on,

Till, behold, the vision gone!

Where hath fleeting beauty led?

To the doorway of the dead.

Life is over, life was gay:

We have come the primrose way.

Underwoods (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890), 21.

An early version of this article was presented at “Portraiture as Interaction: The Spaces and Interfaces of the British Portrait,” a symposium held at the Huntington, Los Angeles, in December 2015. Questions and comments from the organizers, Martina Droth and Mark Hallett, and fellow participants laid the groundwork for my process of revision. Karl Kusserow at Princeton’s University Art Museum and Alan Stahl at the Firestone Library, Clee Edgar and Corinne Hyzny at Upland Country Day School, Barbara MacAdam at the Hood Museum of Art and the Rauner Special Collections Library staff at Dartmouth provided valuable research assistance. Special thanks go to Thayer Tolles for her detailed and thoughtful review of the final manuscript and for sharing difficult to find and forthcoming publications relevant to my argument.

[1] The definitive work on the Stevenson relief is John Dryfhout, “Augustus Saint-Gaudens,” in Metamorphoses in Nineteenth-Century Sculpture, ed. Jeanne L. Wasserman, exh. cat. (Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, 1975), 181–217. Unless otherwise indicated, information about reproductions of and variations on the image is taken from this source.

[2] Will H. Low, A Chronicle of Friendships, 1873–1900 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908), 56.

[3] Low, Chronicle, 53. Low refers here to a well-known sonnet describing Stevenson by the writer’s friend William Ernest Henley. It begins, “Thin legged, thin chested, slight unspeakably.”

[4] Low, Chronicle, 153.

[5] On Stevenson’s friendship with Baxter, Colvin, Gosse, Lang, Low, and others, see “RLS’s Friends and Correspondents,” RLS Website, accessed January 15, 2020, http://robert-louis-stevenson.org/friends/.

[6] Andrew Lang, “Recollections of Robert Louis Stevenson,” North American Review, February 1895, 187.

[7] Edmund Gosse, “Personal Memories of Robert Louis Stevenson,” Century, July 1895, 448; Sidney Colvin, Memories and Notes of Persons and Places, 1852–1912 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1921), 100; and Isobel Field (Belle Osbourne), “The Best of All Good Times at Grez,” in Robert Louis Stevenson: Interviews and Recollections, ed. R. C. Terry (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1996), 70.

[8] Quoted in Margaret Stevenson, “Called Home,” in Interviews and Recollections, 207 n4.

[9] Kay Redfield Jamison, Exuberance: The Passion for Life (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 25. For Jamison’s analysis of Stevenson, see 278–86.

[10] Jamison, Exuberance, 286.

[11] George E. Brown, A Book of Robert Louis Stevenson: Works, Travels, Friends, and Commentators (London: Metheun and Company, 1919), 28.

[12] Low, Chronicle, 215.

[13] Low, Chronicle, 216.

[14] Low, Chronicle, 217.

[15] Homer Saint-Gaudens, ed., The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 2 vols. (New York: Century Company, 1913), 1:373.

[16] Low, Chronicle, 386.

[17] Low, Chronicle, 389. He later changed handsome to “remarkable looking, and like a cinque-cento medallion.” Robert Louis Stevenson to Sidney Colvin, September 24, 1887, in Selected Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. Ernest Mayhew (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997), 245.

[18] Low, Chronicle, 389.

[19] Saint-Gaudens, ed., Reminiscences, 1:373–78; Low, Chronicle, 389–91.

[20] Low, Chronicle, 395.

[21] John H. Dryfhout, The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (Hanover, NH: University of New England Press, 1982), 82–84, 91, 93, 95, 98–99.

[22] Dryfhout, Saint-Gaudens, 107.

[23] Dryfhout, Saint-Gaudens, 172.

[24] Dryfhout, Saint-Gaudens, 181.

[25] Saint-Gaudens, ed., Reminiscences, 1:388–89.

[26] Low, Chronicle, 392.

[27] This quotation is from Cicero, Pro Plancio (II). I am grateful to James Higginbotham for this reference and its translation.

[28] Object file, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Robert Louis Stevenson, 1902, S.963.155, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH.

[29] “To Will. H. Low: In Acknowledgement of the Dedication of His Drawings for Keats’s ‘Lamia.’” Century, May 1886, 73.

[30] Alexis L. Boylan, “Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Robert Louis Stevenson, and the Erotics of Illness,” American Art 30, no. 2 (Summer 2016): 15.

[31] Boylan, “Erotics of Illness,” 27. She contends that the image of Stevenson in bed did not square with his popularity as an adventure writer.

[32] Sidney Colvin to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, March 2, 1894, Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers, Rauner Special Collections, Dartmouth College Library, Hanover, NH [hereafter Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers].

[33] Saint-Gaudens, ed., Reminiscences, 1:388. Stevenson’s bronze medallion was sold at auction after Fanny Stevenson’s death in 1914. It was purchased by George D. Smith, a New York book dealer, and following him, by George Hewitt Myers in 1915. For years it hung in the Textile Museum, which Myers founded in 1925 in Washington, DC. In 2011, the museum became affiliated with George Washington University and the Stevenson portrait was sold at auction on December 1 that year, through Sotheby’s. On May 23, 2017, the estate of Richard J. Schwartz sold it at auction through Christie’s.

[34] “The sinful painter drapes his goddess warm, / Because she still is naked, being dressed; / The god-like sculptor will not so deform / Beauty, which limbs and flesh enough invest.” Low, Chronicle, 394.

[35] Mayhew, ed., Selected Letters, 609–10.

[36] On Gilder’s friendship with and promotion of Saint-Gaudens, see Thayer Tolles, “Augustus Saint-Gaudens, His Critics, and the New School of American Sculpture, 1875–1893” (PhD diss., The City University of New York, 2003), 30–38.

[37] See Arthur John, The Best Years of the “Century” (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981), 112–46.

[38] Richard Watson Gilder to Homer Saint-Gaudens, June 6, 1907, in Letters of Richard Watson Gilder, ed. Rosamond Gilder (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1916), 81.

[39] Herbert F. Smith, Richard Watson Gilder (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1970), 74.

[40] Richard Watson Gilder to Robert Louis Stevenson, February 17, 1883, in Gilder, ed., Letters, 121.

[41] “Stevenson’s ‘New Arabian Nights,’” Century, February 1883, 628–29.

[42] Robert Louis Stevenson to his parents, February 1, 1883, in Mayhew, ed., Selected Letters, 216.

[43] Robert Louis Stevenson to Sidney Colvin, September 18, 1887, in Mayhew, ed., Selected Letters, 343.

[44] Marianna Griswold van Rensselaer, “Robert Louis Stevenson, and His Writing,” Century, November 1895, 124.

[45] Van Rensselaer, “Stevenson,” 125.

[46] William A. Coffin, “The Sculptor Saint-Gaudens,” Century, June 1897, 193.

[47] Tolles, “Augustus Saint-Gaudens,” 294–97.

[48] “The Gallery: The Academy Exhibition,” Art Amateur, May 1889, 127.

[49] “The National Academy Exhibition: The Portraits and the Sculptures,” New York Sun, March 31, 1889, 14.

[50] Edmund Gosse to George Allison Armour, August 21, 1887, in The Life and Letters of Sir Edmund Gosse, ed. Evan Charteris (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1931), 215.

[51] Edmund Gosse to George Allison Armour, January 31, 1891, in Charteris, ed., Life and Letters, 222–23.

[52] Colvin was aware of Armour’s bronze when he received his reproduction from Stevenson and asked Saint-Gaudens if the two were identical. Sidney Colvin to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, March 2, 1894, Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers.

[53] Cable’s relief now hangs in the library of Upland Country Day School, Kennett Square, Pennsylvania. It was given to the school in 1973 or 1974 by Mrs. Demarus Jenks, who inherited it from her father, a Mr. Velie. One of Mrs. Jenks’s three sons, all of whom attended Upland, reported that his grandfather purchased it in Chicago. My thanks to Clee Edgar at Upland Country Day School for this information.

[54] Compared to the unique thirty-six-inch bronzes, for which Armour and Cable paid $1,200, the eighteen- and twelve-inch diameter reproductions cost approximately $150 and $100 in 1908.

[55] Thayer Tolles, “The Puritan as Statuette,” in In Homage to Worthy Ancestors, ed. Henry J. Duffy (Hanover, NH: The Saint-Gaudens Memorial, 2011), 69–84.

[56] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to Louis Saint-Gaudens, July 2, 1899, quoted in Dryfhout, “Stevenson,” 184.

[57] Tolles, “The Puritan,” 84–88. See also Thayer Tolles, Augustus Saint-Gaudens in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009): 56–57.

[58] Thayer Tolles, ed., American Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2 vols. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999, 2001), 1:52–54.

[59] “Robert Louis Stevenson Memorial,” The Scotsman, December 11, 1896.

[60] Quoted in Isobel Strong (Belle Osbourne), “Mr. Stevenson’s Relations with Mr. Colvin,” Critic, October 1899, 886.

[61] Thayer Tolles, “‘Mingled Feelings’: Augustus Saint-Gaudens, American Sculptors and Britain,” Visual Culture in Britain 11, no. 2 (2010): 228–31, doi:10.1080/14714781003784355 [login required].

[62] “An Edinburgh Meeting,” Edinburgh Evening News, November 23, 1896.

[63] W. G. Blaikie Murdoch, “The Portraits of Robert Louis Stevenson,” American Magazine of Art 23, no. 2 (August 1931): 113–20.

[64] Betty Harcourt, “The Unveiling of the Robert Louis Stevenson Memorial,” Overland Monthly, March 1905, 237.

[65] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to Graham Balfour, January 5, 1902, Balfour Letters, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

[66] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to Sidney Colvin, July 18, 1904, Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers.

[67] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to Rose Standish Nichols, January 7, 1899, in Rose Standish Nichols, “Familiar Letters of Augustus Saint-Gaudens,” McClure’s, November 1908, 8.

[68] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to Rose Standish Nichols, January 15, 1899, in Nichols, “Familiar Letters,” 9.

[69] Harcourt, “Stevenson Memorial,” 237.

[70] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to Sidney Colvin, November 10, [1900], Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers.

[71] W. B. Blaikie to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, June 28, 1904, Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers.

[72] Henry Johnstone to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, June 29, 1904, Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers.

[73] Sidney Colvin to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, July 2, 1904, Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers.

[74] Charles F. McKim to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, August 3, 1904, Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers.

[75] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to Rose Standish Nichols, September 23, 1998, in Nichols, “Familiar Letters,” 3.

[76] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to Helen Mears, March 16, 1900, Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers.

[77] Low, Chronicle, 391.

[78] Burke Wilkinson, The Life and Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (New York: Dover Publications, 1985), 370.

[79] “A Great Sculptor,” Century, October 1907, 969.

[80] Wilkinson, Saint-Gaudens, 70.

[81] Coffin’s horizonal relief is currently on loan to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, from Daniel Wolf and Mathew Wolf in memory of their sister, the Honorable Diane R. Wolf. A philanthropist and cultural activist, Diane Wolf generously supported national and local institutions and charities. She served on numerous boards and was commissioner of the US Fine Arts Commission from 1985 to 1990. Saint-Gaudens’s portrait of Stevenson is a most fitting memorial since, like writer and sculptor, Wolf died young, at the age of fifty-three. “Diane Wolf,” The Washington Post, January 19, 2008, https://www.legacy.com/.

[82] Isobel Strong (Belle Osbourne) to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, n.d., Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers.

[83] Saint-Gaudens also expressed this sentiment in defense of the time he had taken to complete the Shaw Memorial. “A sculptor’s work endures for so long that it is next to a crime for him to neglect to do everything that lies in his power to execute a result that will not be a disgrace.” Saint-Gaudens, ed., Reminiscences, 2:78–79.

[84] Maria Oakey Dewing to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, October 7, [1905?], Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers.

[85] Marian MacDowell to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, November 1, [1905], Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers.

[86] Tolles, ed., American Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2:542–43.

[87] For a detailed analysis of Rand’s portrait and her dispute with the sculptor’s widow over ownership, see Thayer Tolles, “The Power of Profile: Ellen Emmet Rand and Augustus Saint-Gaudens,” in Ellen Emmet Rand: Gender, Art, and Business, ed. Alexis L. Boylan (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, forthcoming).

[88] Cox painted an enlarged replica of this portrait for the 1908 memorial exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This painting was acquired by the museum through subscription.

[89] Catalogue of a Memorial Exhibition of the Works of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1908).

[90] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to W. B. Blaikie, n.d., Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers.

[91] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to Henry Johnstone, July 11, 1904, Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers.

[92] Augustus Saint-Gaudens to Helen Mears, March 16, 1900, Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers.

[93] Saint-Gaudens, ed., Reminiscences, 1:388–89.

[94] Quoted in Margaret Stevenson, “Called Home,” in Interviews and Recollections, 207 n4.